An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

May 13th, 2009

Working While Contagious: Why Do We Do This?

File this under, “physicians behaving badly”: The nearly universal MD practice of going to work while sick.

File this under, “physicians behaving badly”: The nearly universal MD practice of going to work while sick.

The ironic thing is we think we’re being selfless — after all, if we don’t show up, our patients will need to be rescheduled, or someone will need to cover, or some administrative/teaching task will not get done — but let’s imagine for a second that we actually asked our patients what we should do.

Answer: Go home. Get better. Don’t infect me.

Or, to quote the signs that have appeared in our hospital since H1N1 hit, “If you have a cough, sore throat, and fever, please do not enter the hospital unless you are here for care.”

(Patients with these symptoms who are here for care are instructed where to obtain a surgical mask.)

One primary care internist, writing in the New York Times, seems to have kicked the habit:

As a resident, my greatest pride was in never having missed a day for illness. I’d drag myself in and sniffle and cough through the day. Once, I’m embarrassed to admit, I trudged up York Avenue to the hospital making use of my own personal motion sickness bag every few blocks while horrified pedestrians looked on. Now, though, I see the foolishness of this bravura.

Sadly, I think she’s in the minority.

May 7th, 2009

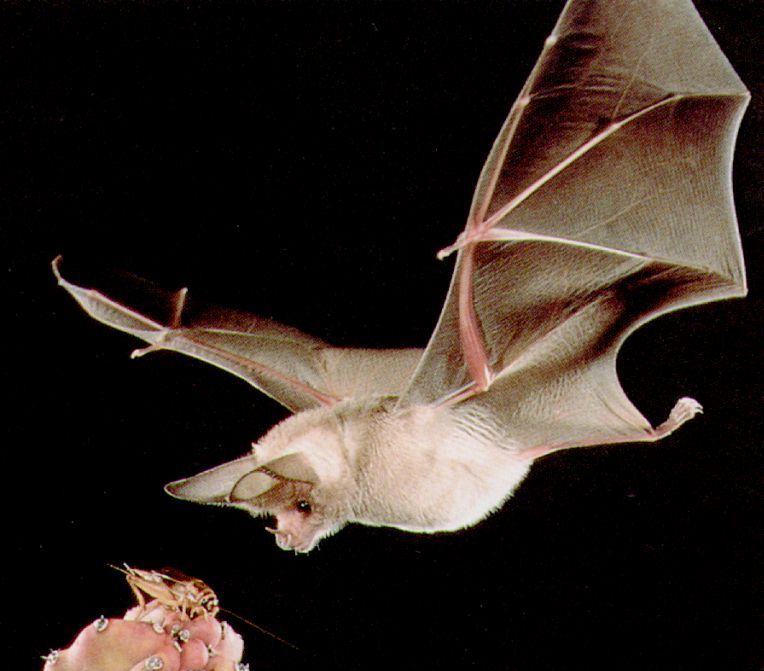

Human Rabies from Bats: Another Look at the Numbers

The gang from Canada is at it again, reviewing human rabies cases from bats and trying to make some sense of the data.

The gang from Canada is at it again, reviewing human rabies cases from bats and trying to make some sense of the data.

(For a summary of their outstanding prior paper in CID, read this.)

But before we get to their latest masterwork, here are some questions to ponder. While doing so, keep in mind the practice of giving the rabies vaccine to a person with “bedroom exposure to a bat while sleeping, without evidence of direct physical contact”:

- Are you more motivated by avoiding an “error of omission” (a mistake from not doing anything) than an “error of commission” (a mistake from doing something)?

- Do you ever envision yourself being named in a lawsuit for failure to provide preventive therapy?

- Do you sometimes imagine yourself cited in a newspaper as the doctor who said, “that isn’t necessary”, only then to have the patient in question be the one in a zillion who gets rabies? (“We called Dr. Freepner, and he said not to do it. Later, she was dead.”)

- Do you feel you have a moral imperative to provide preventive therapy for a condition that will likely be fatal, no matter how unlikely it is that a patient will develop it?

- Do you think cost, limited supply, and personnel issues should always be secondary considerations when making decisions about an individual?

- When you read official guidelines that state that preventive vaccination “can be considered” in low but not zero risk circumstances, do you interpret that to mean it should be given?

- Did you ever find yourself doing something clinically that you just knew made no sense, yet you did it anyway?

I suspect we all could answer “yes” to some, if not all, of the above questions. These are not rational decisions, they are emotional ones.

Hence this latest paper is such a joy to read. It provides yet more evidence that a policy of giving the rabies vaccine to patients with a “bedroom bat exposure” but no contact is, to be blunt, pretty ridiculous. Some of the key numbers:

- Based on a telephone survey done in Quebec, fewer than 5% of people with such bat exposure get vaccinated.

- The estimated incidence of rabies due to this exposure is 1 case per 2.7 billion person-years.

- The number needed to treat to prevent a single case of human rabies from bedroom exposure (but no contact) is around 2.7 million.

- If all potential exposures were investigated and evaluated fully — after all, this is recommended in the guidelines, right? — this would require 49 physicians, 491 nurses, and 259 veterinarians working full-time for a full-year. And this estimate does not even include administration of the rabies vaccine!

In short, what we are doing is absurd — we are giving preventive therapy to a small proportion of the potentially exposed only because they show up, and because we can. It has very little to do with preventing actual cases of rabies, but it sure makes us and our patients feel better.

But if it’s indicated for those who show up, what about the 95% who don’t? Solid quote:

Failure to intensely pursue a greater proportion of eligible persons then becomes paradoxical public policy: a recommendation that is known to be sustainable only if ignored by most eligible persons is of doubtful usefulness and questionable ethics.

So what are we to do? The authors conclude that the recommendations for rabies vaccine for bedroom or other occult exposures “be reconsidered.” I read that to mean, “be scrapped.”

And someone please point me in the direction of why some irrational physician behavior is so hard to shake.

May 3rd, 2009

H1N1! Didn’t You Used to Be Swine Flu?

At the end of last week, “swine flu” became “H1N1”. The CDC web site explains why:

At the end of last week, “swine flu” became “H1N1”. The CDC web site explains why:

This virus was originally referred to as “swine flu” because laboratory testing showed that many of the genes in this new virus were very similar to influenza viruses that normally occur in pigs in North America. But further study has shown that this new virus is very different from what normally circulates in North American pigs. It has two genes from flu viruses that normally circulate in pigs in Europe and Asia and avian genes and human genes. Scientists call this a “quadruple reassortant” virus.

(Note the URL: http://cdc.gov/h1n1flu/swineflu_you.htm. Hmmm.)

Meanwhile, H1N1 (I’ll get used to it) is off the front page of the newspaper, at least the ones around these parts. A sign we’re in the clear, or just our short attention span?

I think you know the answer.

Still, for some very well-reasoned reassurance, I’ve been referring my non-medical friends and family to this excellent summary in the Wall Street Journal by Peter Palese from Mount Sinai. A key point:

Although the swine virus currently circulating in humans is different from the 1976 virus, it is most likely not more virulent than the other seasonal strains we have experienced over the past several years. It lacks an important molecular signature (the protein PB1-F2) which was present in the 1918 virus and in the highly lethal H5N1 chicken virus.

Of course no one really knows what is going to happen — other virulence properties might be present, next year’s seasonal outbreak could be worse, etc — but it’s welcome to hear some balanced views in the mainstream media along with all the hoopla.

April 29th, 2009

Swine Flu Treatment Guidelines — For Now

The swine flu situation is so dynamic that what I wrote earlier this week now seems hopelessly dated — except that from the perspective of a clinical ID doctor, it still feels eerily similar to the anthrax and SARS outbreaks.

The swine flu situation is so dynamic that what I wrote earlier this week now seems hopelessly dated — except that from the perspective of a clinical ID doctor, it still feels eerily similar to the anthrax and SARS outbreaks.

But related to that post — specifically the use of antivirals — these interim guidelines for use of antivirals in suspected cases of swine flu were posted this afternoon on the CDC site. They make good sense.

Note the strategic use of the word “interim”. What are the odds they are unchanged during the next week? 1 in a 1000?

April 26th, 2009

Swine Flu Curbsides: Anthrax, SARS Redux?

In my email in-box yesterday AM from a primary care doc:

In my email in-box yesterday AM from a primary care doc:

A patient of mine, 40 year old woman totally healthy, is going to Cancun on Tuesday for a conference. She’ll be there for 6 days.

I know there are no cases of swine flu in Cancun yet, and the situation is evolving, but here’s my question: what should she do (besides the obvious stuff like handwashing, etc)?? Bring tamiflu?? A mask?? Should she cancel her trip???? [N.B., actual punctuation retained for effect]

Ah, memories of the anthrax attacks and SARS, when an ID threat hits the headlines and people understandably want to know what they can do to protect themselves.

So they turn to their primary care providers, who then turn to us.

And in these situations, there’s the official response to such a question, which as we all know is sometimes different from the practical response — and I define the latter being what would you do for you or your family.

So not only did I say that it would be reasonable to bring some osteltamivir (Tamiflu), I even thought it wouldn’t be crazy to consider a prophylactic strategy — though the fact that she’s totally healthy made me favor the former approach.

And I wonder how many ID docs out there purchased some ciprofloxacin back in 2001, even though we were told not to.

April 20th, 2009

Another HIV Pharmaceutical Partnership

GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer have created an alliance for HIV drug development.

GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer have created an alliance for HIV drug development.

Since there is only one collaborative effort in the HIV treatment area — the colossally-successful “Atripla” between Gilead and BMS — I had thought this kind of arrangement was fairly rare in the drug biz, but according to this interesting take, apparently not.

Perhaps not surprisingly, GSK is a lot more invested in this effort than Pfizer (85/15% split). Great quote:

The structure looks like GSK has a lot more involved than Pfizer, though, so one of the things to watch will be how much effort Pfizer really puts into the new venture. Lip service is just as common a currency in the drug companies as it is anywhere else, and converts at the same exchange rates.

Regardless, it’s nice to see that there is an HIV drug development pipeline still out there, and hence hope for patients with HIV resistance to all currently available drugs. Good table of the combined GSK/Pfizer investigational agents here.

April 18th, 2009

Ceftriaxone and Calcium — OK Again in Adults!

As every house officer, hospitalist, intensivist, and ID doc knows, ceftriaxone and calcium have been contraindicated since 2007 due to fears of a potentially fatal precipitation of the two that led to the death of 5 neonates.

Pediatricians are fond of saying “kids are not small adults” (I should know), and if that’s true, it’s even more so that “neonates are not really really tiny adults.”

So it’s not surprising that follow-up in vitro studies have shown that this is unlikely to be a problem when the drugs are administered sequentially. It’s also not surrising since no case of this fatal ceftriaxone/calcium precipitation had ever occurred in adults, even though ceftriaxone has been one of the most commonly-given antibiotics on the planet for decades.

But now we can give them to the same patient again, so long as the person is older than 28 days, and ceftriaxone and calcium are administered sequentially.

Hooray.