August 19th, 2022

Developing Resident Educators

Brandon Temte, DO

Dr. Temte is a Chief Resident in Internal Medicine at Providence Portland Medical Center in Portland, OR.

We currently find ourselves at the start of another academic year. By this time in August, many medical trainees are settling into new roles. Recently graduated medical students are getting used to hearing Dr. before their name. New senior residents who were interns a short time ago now find themselves leaders of their own teams. As for myself, I am starting a pulmonary and critical care fellowship at a new academic center. By August, all these training doctors are considering the question of how they will lead and teach in their new roles.

Throughout medical school, we have the privilege of being taught by excellent instructors. While all our instructors had various pros and cons, very few of them provided dedicated instruction on how to be leaders and educators. Most residents have observed that their fellow residents doing most of the teaching. Early on, we model our teaching tactics based on what we’ve observed during our own learning. However, I found very quickly as I advanced from medical student to senior resident that it is a bit more complex than teaching others in the way that I would like to be taught. Diagnosing the learner and effectively teaching the student in front of me requires intention and training.

Throughout medical school, we have the privilege of being taught by excellent instructors. While all our instructors had various pros and cons, very few of them provided dedicated instruction on how to be leaders and educators. Most residents have observed that their fellow residents doing most of the teaching. Early on, we model our teaching tactics based on what we’ve observed during our own learning. However, I found very quickly as I advanced from medical student to senior resident that it is a bit more complex than teaching others in the way that I would like to be taught. Diagnosing the learner and effectively teaching the student in front of me requires intention and training.

Residents as Teachers

At my residency program, we were fortunate to be able to create a Residents as Teachers program during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the first few months of 2020, some clinic and elective time was canceled, which created an unexpected opening in our schedules. While we were at home working on research and learning via Teams, a few of us came together with our best teaching attendings and started to create a curriculum.

Luckily, many successful Residents as Teachers programs have been instituted at other programs, and we modeled our intervention after them. Together, we created resident-led workshops, curriculum, syllabus, and an elective rotation. During the 2021-2022 year, we had our inaugural Residents as Teachers session. We focused primarily on instructing second- and third-year residents and were excited to have 9 of the 18 senior residents join our group. As a result of the program, we’ve participated in some excellent teaching workshops, had more resident-led noon conferences, and increased teaching on the hospital wards.

Luckily, many successful Residents as Teachers programs have been instituted at other programs, and we modeled our intervention after them. Together, we created resident-led workshops, curriculum, syllabus, and an elective rotation. During the 2021-2022 year, we had our inaugural Residents as Teachers session. We focused primarily on instructing second- and third-year residents and were excited to have 9 of the 18 senior residents join our group. As a result of the program, we’ve participated in some excellent teaching workshops, had more resident-led noon conferences, and increased teaching on the hospital wards.

One prerequisite for a Residents as Teachers certification was to get involved in a medical education project. This requirement has led to an improved simulation lab, medical student curriculum, and further POCUS teaching. To this day, helping to create and lead the first year of our Residents as Teachers is one of my favorite projects.

Resident Educator Tips – What I’ve Learned So Far

Resident Educator Tips – What I’ve Learned So Far

Resident-led education is so important and can create a meaningful impact for both the teacher and learner. During this last part of the article, I’ll leave you with a few tips I’ve acquired from my mentors. These are not all-encompassing but are a great place to start during your early career as a medical educator.

- Get involved in teaching. This may be daunting at first, especially early in your career. However, we all have something we are interested in and can pass along to our fellow trainees. Practice makes progress when it comes to teaching.

- Create psychological safety. Everyone learns best in a safe environment that is free of ridicule and undue stress. Bloggers on our site have discussed psychological safety before — for those interested in learning more.

- Focus on illness scripts. Many new learners are still building their pattern recognition skills. Comparing and contrasting illness scripts for a presenting illness can solidify clinical reasoning around a particular disease or framework.

- Teach one or two things at a time. Once you find a teaching point or area of improvement, focus on providing instruction around a few key takeaways. Make sure to emphasize the key points you want your learner to remember at the end of the lesson.

- Set clear goals and expectations. Make sure everyone knows how, when, and who will be doing the teaching.

- Prepare a few talks on your favorite subjects. This is your chance to dive deeply into an interesting topic and be the go-to expert on this subject.

- Provide take-home materials. This can be something as simple as a paper to read afterward or a framework you’ve created.

- Seek out frequent feedback. Having a mentor or an educator you look up to provide feedback on your teaching can be an invaluable experience.

- Join your residency’s Residents as Teachers program. If you do not have a Residents as Teachers program, creating one can help expand the education culture of your residency and be very rewarding.

I believe we all have a duty to train the next generation and pay it forward. Improving your skills as an educator will not only help the field of medicine but also improve your skills as a physician. I hope everyone experiences the joy of helping someone along their professional journey.

August 12th, 2022

Beginnings

Abdullah Al-abcha, MD

The Beginning of Fellowship

I was driving from Lansing, Michigan to Rochester, Minnesota and the view of green mountains overlooking the lake was so breathtaking it made me forget the hard work of packing my entire apartment away to begin again, elsewhere. It was something I had never seen before. I was eager to see Minnesota for the first time, just as I had been to see Michigan for the first time. I had heard about the cold weather of both, but my level of excitement was not diminished either time — my goal was much bigger than worrying about the weather. The first move, to Michigan, was for my internal medicine residency, and the second move, to Minnesota, was for my cardiology fellowship. My love of medicine and cardiology dictated that wherever I ended up, which ever state, I would be just as excited to begin my training. As similar as both experiences sound as I describe them, each beginning has been completely different. First, I’d like to begin by thanking whoever came up with the idea of starting training years on July 1st. There is nothing more beautiful than a new beginning in the summer time — it makes me think of how impossible it would be to navigate these changes if we started in December.

The Beginning of Residency

I moved from Houston, Texas, to Lansing, Michigan, for residency. Having already moved from Amman, Jordan, each place was a world apart. My first day of residency in Michigan started at 6 AM in scrubs on an ICU shift. I was given a pager, and I wasn’t exactly sure what would happen after that. An entire new system, and a job that’s actually training instead of school. I felt like I had some of the medical knowledge I needed, but I had to learn to apply it to a new system. In contrast, on the first day of my fellowship, at 6 AM I am dressed in a suit and ready to begin. It feels much slower, and I feel like a beginner again (although an older and more mature beginner). Having completed my residency in a similar setting, I am very well aware of the system and culture of a hospital in the U.S., but I’m am navigating new waters when it comes to knowledge.

When you start residency, you’re learning medicine while figuring out if you enjoy practicing general medicine or whether you’re more interested in a specialty. I was excited about every rotation as a resident. I believe it’s really important to stay open and to welcome every specialty as though could be your favorite. With repetition, you’ll determine what you want to do for the rest of your life. For me, it was cardiology — it had everything I wanted in one profession. The clinical knowledge, the hands-on application, the daily application of hemodynamics, and the long-term patient relationships that I enjoyed from my clinic days. I knew it combined everything I wanted for practice and research and was not just a superficial interest that would wear off.

Combining Beginnings into a Career

It’s very similar in fellowship. Even though we’ve been exposed to the different specialties as residents, the depth of knowledge that you explore as a fellow is astounding. My understanding of an echocardiogram this time last year is a world away from what an echocardiogram means to me today. What’s so interesting about fellowship is that, although you’re at a more advanced level, although it is a stage after completing internal medicine training, you’re a complete beginner when it comes to the science. In residency, I learned how to put a puzzle together, but now I’m learning what each puzzle piece is made up of chemically and physically and the spatial arrangement it requires to create the picture. It has pushed me to go back and refresh my knowledge about basic concepts in physics! I meant it when I said I was navigating completely new waters.

Although the beginnings of medical school, residency, and fellowship are completely different, what’s important is to be excited and interested in each beginning. To invest time and energy and to enjoy them. We get hung up on mastering anything new, and we want to fast-forward until we achieve that mastery — we forget to enjoy the learning process. The beginnings are the most important steps. They are what everything is built upon, so enjoy building a solid base, and don’t rush!

August 4th, 2022

Uncertainty in Medicine — The “July Effect” and Beyond

Khalid A. Shalaby, MBBCh

When I first started residency, I was uncertain and hesitant with most of my clinical decisions. As medical students, we gain considerable knowledge through our medical school curriculum. But gaining knowledge and applying it to practice are two different sets of skills. Because I followed medical school graduation by a hiatus doing bench research, I needed support in both for both kinds of skills when I started residency. I had to brush up on my medical knowledge, and I had to apply it to practice as well as I could. My confidence in my abilities was rather low at that point. But with a lot of support and constructive feedback in the first few months of residency from mentors and colleagues, I was able to improve significantly.

The “July effect”

The public and some physicians fear the “July effect” — when freshly graduated physicians start practicing. Many presume that there is a drop in the quality of care in teaching hospitals during this month. However, the direct supervision of seniors and attendings in academic institutions, the eagerness of every recently graduated physician to do right by patients, and clinical studies all refute that notion.1 As residents become familiar with the practical aspects of the healthcare system and gain clinical exposure, they grow more confident. Personally, I am a bit more fearful of the “January effect” — when the stringent supervision of senior residents wanes, sleep deprivation piles up, and the long nights of winter break morale.

Uncertainty is everywhere

It is inescapable to have some degree of uncertainty when practicing medicine. It is a deeply uncomfortable, anxiety-generating feeling that afflicts many clinicians to varying degrees. This encompasses uncertainty regarding correct diagnoses, prognoses, best therapeutic approachs, mildly abnormal lab values, and imaging studies of undetermined significance. Perhaps the most glaring example is the COVID-19 pandemic. We can all recall how we didn’t fully understand its pathophysiology, and we didn’t how to prevent or treat it when the first wave of cases hit. We are yet to understand its full long-term effects on our patients. But beyond COVID-19, more subtle examples of uncertainty exist in our everyday practice.

I noticed during my chief year that residents (on average) tend to be less hesitant in their answers and more swift in their judgment midway through residency than by the end of training. It’s that sense of confidence that one gets with some (but not a lot of) experience. It’s knowing the presentation and treatment of the most common diseases and seeing enough of them to go into auto-pilot mode but not having enough experience to know ambiguous presentations and handle complications. The realization and feeling of humility that one cannot reasonably encompass all that knowledge and practice expertise typically sinks in during the last few months of residency.

Avoiding pitfalls

It’s only natural to try to rid ourselves of these uncertainties. Therein, we can fall prey to pitfalls. We can turn to defense mechanisms might harm our patients, affect our own wellbeing, and impact the healthcare system at large. Suppressing uncertainty can lead to anchoring bias and misdiagnosis. It can lead to dismissing patients’ symptoms when they doesn’t fit a certain disease category, falsely attributing symptoms to psychosomatic disorders, or shrugging off patients’ fears about abnormal investigations. Or it can also lead to the exact opposite — doing extensive workups that could be more injurious to patients and burdensome to the healthcare system because of litigation fears.

In a recent study, primary care physicians, physicians with fewer years of experience, and physicians who lack a trusted advisor had a lower tolerance for uncertainty. In turn, physicians with lower tolerance of uncertainty had a higher likelihood of burnout, were less likely to be satisfied with their career, and were less engaged at work (NEJM JW Gen Med Jul 1 2022).2

How can we handle uncertainty in medicine?

We must continue to learn from every patient encounter. Every patient can educate us about their disease process and the adverse effects of a medication or procedure. No matter how many times we’ve diagnosed and treated patients with that disease, there’s always something new. I urge myself and others to tackle topics we’re least comfortable with headfirst, especially during training. Whether you find hyponatremia confusing, headaches difficult to diagnose accurately, or low back pain challenging, expand your knowledge about these topics and watch them gradually turn into your favorite topics.

But expanding your knowledge will only carry you so far. Uncertainty might be a greater challenge for generalists, such as hospitalists, primary care, family, and emergency medicine physicians who see a variety of pathology, but it still looms over even the best subspecialists who focus on a single disease category. Practicing tolerating uncertainty can aid us in making more thoughtful clinical decisions. Having a mentor/advisor during and after graduation from training programs to call on in a time of need is one of the greatest resources. We should discuss and be open with our colleagues and trainees about uncertainty. It may be helpful to receive official training in tolerating uncertainty. Perhaps most importantly, we need to partner with our patients by being honest and forthcoming about the limitations of science and medicine. Shared decision making is of paramount importance, especially when uncertainty is high. As the frontiers of science and medicine continue expanding, we’ll simultaneously have more answers and create more questions. Uncertainty in medicine is probably here to stay and the better we handle it as physicians, the more our patients benefit and the more at peace we’ll be.

- Metersky ML et al. Rates of adverse events in hospitalized patients after summer-time resident changeover in the United States: Is there a July effect? J Patient Saf 2022; 18:253. (https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000887)

- Begin AS et al. Factors associated with physician tolerance of uncertainty: An observational study. J Gen Intern Med 2022; 37:1415. (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06776-8)

July 28th, 2022

10 Tips for July (and Beyond)

Madiha Khan, DO

For new trainees, starting July in the ICU can be the steepest of all learning curves, because the patient acuity and workflow can be overwhelming. The same is true for new fellows, I’ve found, as I started this month in the CCU. Although it is the same unit I worked in twice before as a resident, my new role encompasses more responsibility, contrasted with a more specialized focus in a highly complex subspecialty field. Working alongside the interns and trying to impart practical advice has offered me a unique perspective to be able to understand the gravity of both ends of the spectrum, while recognizing I still have a very long road ahead. In all honesty, these transitions, while an honor, are also hectic and ever changing and require adaptability on a moment-to-moment basis. Thankfully, I’ve learned a few key principles that have helped me pivot, adjust, and transition over this time — I still refer back to them.

1. Become comfortable being uncomfortable.

It’s no secret that the zone of growth occurs outside your comfort zone. I think we are actually better at this at the beginning of the transition period, where seemingly everything is foreign and uncomfortable. Inevitably, after getting the hang of a few things, it becomes harder not to cling onto familiar aspects and to continue to be in the growth mindset, and that’s when this reminder comes in handy most.

2. Work hard first, work smart later.

Being a new trainee, it feels like everyone above you can do your job, and can do it much quicker. Aside from streamlining the technical parts of the day (like reorganizing your EHR dashboard in a more efficient way), no hacks really shorten the process. Trying to do as much as possible yourself is cumbersome, but repetition and volume are the only ways to identify shortcuts without compromising the process.

3. Prioritize asking questions over having all the answers.

Remember to ask “why.” It’s good to have all the data points and lab values ready, but understanding the context in which they exist is crucial. It may seem like a win to finally identify and accurately present the worsening creatinine trend, but it is more important to ask why it is increasing.

4. Have the energy to learn.

What you put into training is what you get out of it. Every training program has a curriculum and didactics; however, being proactive in your own education allows you to address your own areas of weakness at your own pace.

5. Own your mistakes. Have a high tolerance for failure.

Everyone makes mistakes, but the way they handle making a mistake is what truly matters at the end of the day. Acknowledging the error is the crucial first step; only after owning the misstep can you truly be honest and clear about the thought process and identify areas for improvement.

6. Communication is key.

Breakdowns in communication are the breeding ground for mistakes and adverse events. Making sure everyone on the team is on the same page can be the most effective way to move things along in a hospital, and learning how to convey plans and ask questions clearly is a necessary skill to develop early.

7. Seek to simplify.

If you’re unable to explain a concept without overusing jargon, it may be an indication that you haven’t fully grasped it. Not to mention, shared decision making with patients is an important pillar of patient care that often falls short because of the clinician’s inability to simplify.

8. Embrace technology.

Are you having trouble keeping track of all your tasks? There is an app for that. Becoming comfortable with applications you use every day can save you hours of time in the future: from using templates for emails to utilizing a cloud-based server to access documents and educational materials across a variety of devices. Incorporating automation in your day-to-day routine can significantly improve your quality of life. (That being said, you don’t have to love every Epic update!)

9. Know when to say no.

No matter how many resiliency modules you complete, the compounded toll of being a trainee inevitably leads to some degree of burnout and exhaustion. Eating right, sleeping well, and working out seem to be the consistent advice to battle burnout — but equally important is to honestly assess your bandwidth to participate in extra curricular activities outside of training.

10. Make the table bigger.

Last but not least: root for others to succeed. There is enough success in the world for everyone. One of my favorite Twitter threads by author Rebecca Makkai outlines this idea beautifully. Even though she specifically talks about the arts, this idea absolutely applies to the world of academia.

July 19th, 2022

Adventures of Family Medicine Clinic Days

Mikita Arora, MD

Tuesday Clinic as a PGY-2 with Dr. Kelly Mason (APD), Dr. Hima Chopra, Dr. Mark Schury (PD), me, and Dr. Whitney Fron

Family Medicine Continuity Care Clinic

Wow! I cannot believe it’s my final year of residency. I am currently a 3rd-year Family Medicine Resident at McLaren Oakland Hospital in Pontiac, MI. Our clinic is a nonprofit, federally qualified health center and an accredited patient center medical home. Our target population is the medically underserved in an urban setting. The patients who come to our clinic are very sick. Many of them haven’t seen a doctor in years. If they do see a physician, most of them are noncompliant. Their problem list is sometimes 8 to 10 assessments deep. Their problems have to be addressed at every visit, because either they are critical or you don’t know if you will ever see them again.

We provide them with lots of resources: access to a nutritionist, shelter, or counseling and rehab programs. The environment that my program director, Dr. Mark Schury, and associate program director, Dr. Kelly Mason, have created is very supportive and a magnificent one to train in. As a third-year resident, I have two clinic days and see as many as 16 to 18 patients per clinic day. These interactions with my patients have opened my eyes in numerous ways.

Clinic Patient Adventure

One of my very first clinic patients impacted my training tremendously. She has helped me grow into the physician I am today. When I first met, her health was already deteriorating, and she was very noncompliant with medical advice. In August of my intern year, I remember telling her, “Hey, you are drowning in your body’s fluid. You need to go to the hospital. There isn’t much I can do for you here anymore.” She would tell me how she hated the hospital and did not want to go. Finally, 6 months later, I was able to convince her to go to the hospital.

During that hospital stay, I went to visit her, because our hospital did not allow outside visitors due to COVID restrictions. I remember how happy and grateful she was to see me. We were chatting and having such a good time. Suddenly, our conversation was interrupted by the internal medicine attending. He asked her a simple question, “What do you eat every day?” Her response was “Ramen noodles and sometimes eggs.” The attending stated, “That explains everything,” and walked out. My heart sank. This was my clinic patient, and I did not know she did not have access to food. I had never even asked her what she ate.

During the past 2 years, I had seen her at the clinic whenever she came in, and she had shared her life stories with me. I had become her confidant. As family medicine physicians, we form bonds with our patients, which turn into lifelong relationships. Our patients trust us with their health. We listen to their problems and help solve them. However, we cannot fix a problem that we are unaware of. And I never asked her what she ate.

Recently, she was hospitalized again. When I went to see her, she was a zombie. Her nurse told she had overdosed on hydromorphone. I thought to myself, “Where did she even get it?” So I looked up her name in the Michigan Automatic Prescription System. She had told me she was taking Norco, prescribed by her pain management doctor. However, I did not know that she was also being prescribed hydromorphone. She had left out the other pain medications she was taking.

What I Learned from this Patient

-

- One of the greatest lessons that I learned from her was asking the right questions. If you don’t ask the questions in a certain way, you will not get the answers you need. The answers are there, but you need know how to find them.

- Food insecurity is a healthcare problem. If your patients don’t have access to healthy foods, then they will continue to be sick from eating processed food. My goal is to create access within the community through a community service project. More to follow in a future post!

- Communication among providers is the key to providing excellent patient care.

- The power of the physician is the ability to heal, but sometimes it’s the patients who really heal us.

It’s our job to educate the patients, but they are ones teaching us something new every day.

June 29th, 2022

The Talent Code of Residency Training

Abdullah Al-abcha, MD

After spending 4 to 6 years in medical school, physicians typically spend 3 to 7 years in residency training. Residency training is a crucial step that shapes us as physicians. We spend long hours at the hospital taking care of patients, and we learn directly from these encounters. We also spend a lot of hours studying, and learning the science behind what we do, and why we do things in certain ways. These two experiences go hand in hand and complement each other to prepare us to become practicing physicians.

A common question that almost all trainees think of before starting residency is, “what are the best ways to learn, grow, and excel in residency?” In this article, I’ll try to summarize my answer based on Daniel Coyle’s book, The Talent Code.

In The Talent Code, Daniel summarizes his experiences of visiting what he describes as “talent hotbeds” around the globe. Talent hotbeds are places that produce many “talented” people. Daniel argues that talent and greatness aren’t born, they are grown. He comes up with 3 essential factors that are needed to reach greatness — deep learning, ignition, and master coaching. Daniel provides excellent examples of how these factors have been applied in different hotbeds.

Deep Learning

Deep learning is based on trying, failing, and trying again to fail less. Daniel explains in the book that this is a way to build myelin, and myelin is the key to talent. The problem in medicine is that failure to recognize a disease or inappropriately treating a disease affects patients’ lives. Thus, failing in medicine is dangerous. However, this is the reason we complete residency. As a junior resident, you practice under the supervision of a senior resident, a fellow, and an attending. You have a safety net of multiple layers.

The practice of medicine is based on recognizing patterns and making the correct diagnosis. The more you try to recognize a pattern, the more myelin you build, and hence you get better at recognizing patterns. Trying and failing is an uncomfortable feeling. Unfortunately, it’s key in the process of learning. It takes courage to speak or answer a question when you’re not certain about the answer. However, as a junior resident, you won’t be certain about most things. And by not taking the chance to share your thought process, you’re missing out on trying, failing, and reducing the likelihood of failing the next time you try.

The practice of medicine is based on recognizing patterns and making the correct diagnosis. The more you try to recognize a pattern, the more myelin you build, and hence you get better at recognizing patterns. Trying and failing is an uncomfortable feeling. Unfortunately, it’s key in the process of learning. It takes courage to speak or answer a question when you’re not certain about the answer. However, as a junior resident, you won’t be certain about most things. And by not taking the chance to share your thought process, you’re missing out on trying, failing, and reducing the likelihood of failing the next time you try.

Another important thing for junior residents is to ask questions, especially when in doubt or if a decision doesn’t make sense to you. Asking in front of the entire team offers an educational opportunity for yourself, the students, and other residents in the team. if you don’t feel comfortable asking in front of the entire team, ask your senior resident or the attending privately. The idea behind this is that treatment plans should make sense to you. Understanding the pathophysiological and pharmacological processes behind a disease and its treatment plan is crucial. It will make it easier to store the information and recall it in the future. Mere memorizing might help in the short term, but understanding will help you retain the information long-term.

Be aware of biases, especially anchoring bias. Anchoring bias is a cognitive bias that causes us to rely too heavily on the first piece of information we are given about a topic. An example of anchoring bias is staying focused on the initial impression of a patient case (it can be your impression or an impression presented to you) even though new data doesn’t support that impression. Always try to keep an open mind about what causes, and remember that new data are as important as the initial data.

“When you hear hoofs, think horse, not zebra.” This is a common saying in medicine, and one of my favorite attendings, Dr. Muhammad Nabeel, used to remind me of it whenever I start thinking of rare diseases before excluding common ones. As new residents, you need practice to refine your thought process to think of the more common conditions first. You still need to keep the rare ones at back of your mind and think about them when common diseases don’t explain your patient’s condition, but they should not be your first thought.

In a nutshell, as Daniel puts it, deep learning is like a staggering baby learning to walk. Your senior residents and attendings will be there to ensure a safe environment for you to try but you need to keep trying, despite failing again and again.

Ignition

Deep learning requires motivational fuel to sustain it. Daniel discusses how ignition starts from a moment where we said “this is who I want to be.” This moment ignites an inner force that pushes us to achieve a set goal. However, it might be difficult to keep the ignition firing through the years. First, find what motivates you and keeps you going. Second, surround yourself with a support system of family, friends, and mentors. Whenever things get difficult, remind yourself of what motivates you, and confide in your support system to help you remember.

Master Coaching

Daniel emphasizes the importance of master coaching (mentorship), and I completely agree, specifically in residency training. Most trainees think of mentors as a single person that is assigned by the program to monitor their progress and guide them throughout residency. However, residency is a complex journey that requires guidance in multiple aspects, including, but not limited to, education, research, career goals, and personal life. You can have different mentors, each for a different aspect of training and life. Additionally, seeking feedback is crucial. Seek feedback from each of your supervising residents, attendings, and co-interns. Seek feedback often — every 2 weeks, not just at the end of the rotation. This way your mentors can observe your changes, and you hopefully will see the progress.

I have been fortunate to have a great support system to guide me throughout life and residency. This started with my parents who showed me commitment and perseverance, with my partner who supported and guided me through the most difficult times, with senior medical students who led me through the path to residency in the U.S., with senior residents who taught me and provided me with constructive feedback, with attendings who guided my research projects and my career, and with my personal choices.

In addition to the 3 factors that Daniel discusses in The Talent Code, a fourth factor is also vitally important — it’s wellbeing!

Wellbeing

To continue the process of deep learning, to stay motivated, and to keep a successful mentor relationship, you need to be in a good physical and mental state. Residency training requires working for long hours under stressful situations, and residents’ burnout is a nationwide problem. Finding a way to deal with stress is crucial to keeping performance at the same level throughout residency. In my experience, one of the important factors to maintain wellbeing is sleep!

Unfortunately, sleep is the first thing to be sacrificed by trainees. This is most commonly due to institutional and scheduling restraints like 24- and 30-hour shifts. Thankfully, my program (and many others) has eliminated these long shifts. However, even with shorter shifts, trainees pay less attention to their sleep routine. Sleep deprivation among residents is associated with impaired executive function, slower cognitive processing, and increases systemic inflammation (Med Educ 2021; 55:174). Prioritizing sleep, and maintaining a good sleep schedule that works for you, is an essential part of wellness during residency.

Maintaining a regular exercise routine and a healthy diet helped me during my residency training. This is much easier said than done, especially during heavier rotations, but maintaining these behaviors is important as you’re under more stress during these months.

Residency programs are required by the ACGME to address the psychological, emotional, and physical well-being of trainees. There are institutional level recommendations to achieve this. However, the ACGME has its own well-being recourses for trainees, including the AWARE podcast, and the AWARE app that focuses on individual level strategies to build resilience and cultivate mindfulness.

Nevertheless, we are all different, and in that difference is where our excellence lies. We learn, we grow, and we become the best versions of ourselves in our own ways. There is no method that works for everyone. What worked for me might not necessarily work for you! So find out what DOES work for you. Lastly, make sure you enjoy the journey, because there is nothing more rewarding than practicing medicine! It may sound like a cliché, but it will end in a blink of an eye, so make those mistakes, fail, ask, and grow.

June 22nd, 2022

In a Digital World, Is “Legwork” Obsolete?

Khalid A. Shalaby, MBBCh

Our 2021 class of interns was the first in our institution not to receive good old pagers. Many institutions around the country are following suit. This marks a milestone in the advancement of how we communicate in medicine. Gone are the days when residents had to step on toes as they left from the middle seat of a packed grand rounds auditorium to answer a page that now can easily  be answered in a text. We have been heavily reliant on outdated technology like pagers and faxes in healthcare communication, and even though we continue to rely on them in some instances, we are now mostly utilizing secure messaging via HIPAA-approved cell phone applications. As healthcare is rapidly being digitized, is there still a need for “legwork”?

be answered in a text. We have been heavily reliant on outdated technology like pagers and faxes in healthcare communication, and even though we continue to rely on them in some instances, we are now mostly utilizing secure messaging via HIPAA-approved cell phone applications. As healthcare is rapidly being digitized, is there still a need for “legwork”?

There is no denying that digitized healthcare is making strides in ease and efficiency of communication. It has arguably made our patient care safer and more timely, fulfilling some of the Institute Of Medicine’s domains of healthcare quality. While secure messaging is undoubtedly very convenient to answer simple patient care questions from different healthcare team members in real time and to provide updates on a plan that is already in place, it is not meant for nuanced discussions and complex plans of care. All too often, I’ve witnessed myself and others rely too much on secure messaging or electronic health records (EHR) documentation for communication.

During my first weeks of residency, I had a prolonged back and forth text exchange with one of the overnight nurses about a cross coverage question — that left me quite confused. My senior resident who was sitting next to me picked up the phone and advised, “Just call. It’s easier that way.” He was right. As silly as it sounds, it was like I had forgotten that other modes of communication existed. That phone call resolved the questions regarding patient care quite quickly. It was then that I first realized there is a downside of overreliance on digital communication.

Secure messaging has many pitfalls, one of which is misunderstanding. Especially when trying to convey a complex situation, a simple misunderstanding can have a lot of downstream effects. We cannot appreciate the tone, the level of urgency, the full context, or occasionally even the multiple acronyms used by our colleagues in different specialties. I’ve witnessed many disagreements between different services or healthcare members over secure messaging, but rarely do such disagreements happen during a phone or in-person conversation.

Secure messaging has many pitfalls, one of which is misunderstanding. Especially when trying to convey a complex situation, a simple misunderstanding can have a lot of downstream effects. We cannot appreciate the tone, the level of urgency, the full context, or occasionally even the multiple acronyms used by our colleagues in different specialties. I’ve witnessed many disagreements between different services or healthcare members over secure messaging, but rarely do such disagreements happen during a phone or in-person conversation.

In the past, nonurgent communication with healthcare team members was done primarily on rounds, but now, the answers to all questions are just a text away. The ease with which we can communicate has led to an overwhelming number of messages every day for all clinicians, with the interruptions of an incessantly buzzing phone, making it harder to focus on the task at hand. Not to mention the effects of constant texting on fatigue and burnout among healthcare professionals.

When placing a consult and waiting for recommendations, I have found it most useful to speak directly with consultants. They almost always welcome a call and are happy to hear our thought process and clinical questions. I learn something from each of these conversations. At times, it’s still beneficial to walk over to the radiology department or the lab/pathology department to have a discussion, provide the clinical context to narrow down differentials, and talk over complex patient care.

When placing a consult and waiting for recommendations, I have found it most useful to speak directly with consultants. They almost always welcome a call and are happy to hear our thought process and clinical questions. I learn something from each of these conversations. At times, it’s still beneficial to walk over to the radiology department or the lab/pathology department to have a discussion, provide the clinical context to narrow down differentials, and talk over complex patient care.

Every generation of healthcare professionals deals with unique challenges. This is certainly one of many we face, especially for those of us who trained entirely in the “post-pager” and EHR era. We must find a way to reap the benefits that technology offers in healthcare delivery and communication and leverage its powers to serve our patients without falling for its shortcomings. This is not a call for resisting the advances in healthcare communication, but rather an acknowledgment of its downsides and a reminder for the need of continued improvement. The answer probably lies in smarter technology and more fluid inter-operability of software. Regardless, we will always need the human touch in healthcare. As these changes continue to shape our healthcare universe, I remind myself and others to be patient, to be kind. Realize that the resolution to a lot of problems can just be a face-to-face/screen-free conversation away.

June 16th, 2022

Dear Chief Year …

Madiha Khan, DO

If you ask anyone on Reddit or SDN (Student Doctor Network) about pursuing Chiefdom in residency, you’ll find numerous opinions about it being an undertaking not worth the burden of additional responsibilities, even if it is considered an honor. I was also advised gently — and accurately, in my opinion — by mentors that focusing on research would lend itself to a ‘stronger’ fellowship application, because chief selection is not standardized across all programs, which makes it difficult to gauge just how much of a positive it is. (Particularly when it is not the traditional extra year as a PGY-4.) Honestly, while I never thought it would help secure a fellowship spot as much as other pursuits might have, I did feel that it would invaluable for an eventual career in academics. Besides, I love emails, email templates, and the slew of operational management conundrums that most people dread, so I thought perhaps the addition of administrative responsibilities wouldn’t be that much of a time-sink for me, at least.

I was wrong.

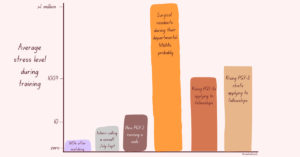

Truthfully, since the day my two co-chiefs and I were elected in March 2021, it has been a humbling, non-stop grind, with moments of self-doubt and even regret about our choice at times. For me, balancing chief duties with clinical responsibilities while also applying to fellowship made it easily one of the most stressful periods of residency (a rough scale of my individual perception of average stress levels in training is included below). However, reflecting back on this time, these struggles yielded not only great personal growth, but meaningful improvements for our program that made this grueling experience a success and truly worth it in the end… and sometimes, even fun.

At our mid-sized program, the three chief residents (typically PGY-3s) function as one unit. There are no designated roles or distinct labels for each chief (e.g., curriculum or administrative chief). Instead, we had the internal autonomy to divide all educational/administrative work amongst ourselves. For this reason, my experience of having a “successful” chief year is intertwined with the experience of my beloved co-chiefs. Although we spent the past year speaking as one voice, I want to share some insights regarding the challenges and successes of this past year, as one leg of an objectively solid tripod.

Positive Feedback Loop

Positive Feedback Loop

Now that the year is nearing a close, we feel very fortunate to be able to look back at this journey with both pride and contentment that our conscientious leadership was mostly well received and met with tangible positive results: From implementing changes behind the scenes to changes that directly affected residents on a day to day basis.

Since ‘improvement’ can be subjective, not every change was met with enthusiasm, and the sting of rejection would unearth feelings of demotivation. However, with each win, we felt more equipped to cast our net wider and diversify areas of improvement, to a point where it felt like an avalanche of changes in a short amount of time. Win, lose or draw — we learned a lot about the process of getting good ideas approved, and subsequently, getting them practically implemented. Although we became more efficient, the workload did not seem to shrink, as more complex issues required more well-thought out solutions. But, the snowball of successful changes provided the confidence and fuel to take on more, and this was one of the key aspects that blunted burnout. The momentum of approvals energized us enough to keep asking “what else can we improve?”

No Chief Is an Island: Being Set Up for Success

Several months into the chief year, we had made a lot of changes. Internally, we had overhauled our workflow for making schedules and fairly utilizing jeopardy coverage (read: got intimate with Excel), beefed up for recruitment season by investing in the residency social media, and gave the residency website a facelift while also troubleshooting ways to make it secure enough to serve as a platform for internal learning. In the midst of recurrent whiplash of virtual versus in-person mandates, we brainstormed ways to keep the didactic and clinical curriculum robust by negotiating with other subspecialties to find a sweet spot between coverage and teaching that worked for the residents. Somewhere along the way, we also hosted a regional conference for the local IM programs, but my memory of that time is limited to this picture:

I list all this not to provide a laundry list of tasks we accomplished, but to convey that these changes would not be possible in such a hectic and dynamic environment without:

1) Motivated residents that took the time to give fair, honest, and frequent feedback during growing pains. When all parties have a vested interest in the future of the program it ensures a better experience not just for the current residents, but future ones too.

2) A Program Director and faculty willing to listen and seriously consider proposals, and advocate for residents.

3) A Program Coordinator that guided us through the basics, which gave us the opportunity to not only understand the context of the duties of chief residents, but to also reach beyond and enact practical change while respecting the ecosystem in which a program operates.

Chief residents (PGY-3) are not yet viewed as full-fledged programmatic leadership and also not quite viewed as an average resident. It is this unique perspective of access to bits of privy information that allowed for identifying gaps in the optimal resident experience (whether curricular or wellness related) and the ability to implement changes.

Long story short — this is how we lobbied for and secured a ping pong table for the resident lounge.

X+Why: The Biggest Improvement I’ll Never Experience

Mid-morning of December 1st, aka Fellowship Match Day, my co-chief Ibrahim and I breathed a sigh of relief: We had matched! Although our co-chief Rafid was spared from the second round of ERAS as a future hospitalist, he probably breathed a sigh of relief too, maybe even deeper than either of us. At this point we had been ‘chiefing’ for more than 8 months. In that time, we had made a lot of strides. We felt good about our work and felt even better that we successfully matched, despite spending so much time on things outside of the fellowship match. Then, later that day, we received a text from our PD:

Great work guys! Now onto finishing the X+Y schedule, that will be your real legacy as Chiefs.

Up until now, I had thought our legacy was the ping pong table, or maybe shortening the deadline to request PTO. During the commotion of the first half of the year, we had put implementation of a totally new and improved scheduling model on the back burner. Briefly, our program functioned with the traditional model of clinic, meaning that during inpatient months we would leave for a half day to go to our continuity clinic, and it was now time to switch to a more progressive system.

Instead of providing a walkthrough on transitioning to X+Y, as this can be program dependent, I will share the factors that helped us rally to undertake the biggest improvement yet.

Beyond the three of us genuinely sharing the unified goal of improving the program, I would say the most important aspect of undertaking such a task was the fact that we had the confidence and trust of our leadership to take the reins and be successful and were given the bandwidth to do so. Micromanaging can quickly handicap motivation. We were set up for success because we weren’t limited by micromanagement. To be clear, we did go back and forth on details, but amongst each other — so by the time we were ready to propose our suggestions, we had a good understanding of what criticisms could arise. Thus, we felt pretty confident that our proposals would be approved, as they were extensively hashed out. Of course, systemic changes need thorough consideration and approval; however, anticipating the points that would need longer review time helped us build out a timeline that contained no lag between waiting for an answer and continuing to work on the objective.

Another crucial aspect to our success was our ability to problem-solve and internally navigate disagreements (of which there were many). Once, while creating the new curriculum, I called my co-chiefs to debrief after a particularly pugnacious day. I apologized for being stubbornly against some of the suggested changes. Then, Ibrahim said something that really struck me: There is no need to apologize for disagreements. I love and value our disagreements, because the best ideas have come to the surface when we don’t agree.

(I hope this story also gives enough context to an inside joke between us about Ibrahim: Is he the Wisest Young Man or the Youngest Wise Man?)

Would I Do It Again?

Make no mistake, PGY-3 chief year is as busy and involved as you’ve heard. Between the clinical and educational responsibilities, scheduling, recruitment, and countless administrative tasks, it is a jam-packed year. For me, however, the value of what I’ve learned about the educational system, navigating inter-professional hurdles between residents, and practicing the language of diplomacy that is required to implement changes that affect a wide range of people is invaluable. So yes, I would do it again in a heartbeat — serving this wonderful group of residents, alongside my spectacular co-chiefs, has been one of the biggest honors of my life.

June 9th, 2022

Building Possibilities in Family Medicine

Mikita Arora, MD

June is such an exciting month. As the academic year ends, I cannot help but reflect on my PGY-2 year. It was filled with adventure, because I had a leadership role with the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). I was elected as the National Resident Delegate to the Congress of Delegates last July. You’re probably wondering what that means. Honestly, I had no clue either, prior to the AAFP National Convention. However, it has changed my life.

AAFP National Conference

If you’re a medical student or resident who is considering Family Medicine, you should definitely attend this conference. As a medical student, I was told many times how amazing this conference is. However, it’s hard to believe that until you experience it yourself. I feel that it should be a mandatory field trip for all medical students! It’s a great way to connect with family medicine residency programs prior to the interview process. They have this huge exhibit hall where over 500 residency programs have booths organized by states. It gives you an opportunity to meet the faculty members and residents at various programs, which gives you a feel for the program.

Prior to attending this attending this conference, I had looked at programs through their individual websites and thought about whether they would be a good fit for me. But after attending the conference, my opinions about programs changed. When you meet some of the faculty members and residents, you can instantly connect and decide if you want to be a part of their program. The programs will scan your ID, indicating that you visited their booth. After the convention, you should keep in touch with programs you visited and are interested in, because this can help you get an interview! The AAFP also offers scholarships to attend this conference. Be sure to ask your state chapter about this.

Prior to attending this attending this conference, I had looked at programs through their individual websites and thought about whether they would be a good fit for me. But after attending the conference, my opinions about programs changed. When you meet some of the faculty members and residents, you can instantly connect and decide if you want to be a part of their program. The programs will scan your ID, indicating that you visited their booth. After the convention, you should keep in touch with programs you visited and are interested in, because this can help you get an interview! The AAFP also offers scholarships to attend this conference. Be sure to ask your state chapter about this.

AAFP Resident and Student Congress

Another exciting event that happens annually is the AAFP Resident and Student Congress. Last year, I was appointed as the alternate resident delegate from Michigan.  As a delegate, you are encouraged to write resolutions. So what are these resolutions? They can be about anything that you are passionate about! Previous years’ resolutions included women’s rights, gun safety, creating a national database for advance directives, and paid parental leave during residency. After these resolutions are written, they are then passed or rejected by the student and resident congresses. If they are passed, they are sent to the one of the AAFP commissions, where the members work on implementing the resolutions’ directives. The USMLE becoming pass/fail was a resolution that was written at the convention. Pretty cool right? You have a voice that matters, and you can actually do something to make a change!

As a delegate, you are encouraged to write resolutions. So what are these resolutions? They can be about anything that you are passionate about! Previous years’ resolutions included women’s rights, gun safety, creating a national database for advance directives, and paid parental leave during residency. After these resolutions are written, they are then passed or rejected by the student and resident congresses. If they are passed, they are sent to the one of the AAFP commissions, where the members work on implementing the resolutions’ directives. The USMLE becoming pass/fail was a resolution that was written at the convention. Pretty cool right? You have a voice that matters, and you can actually do something to make a change!

At the convention last year, I was elected as one of the two National Resident Delegates to the AAFP Delegate of Congress. This role taught me the importance of advocacy for myself, my patients, and my collogues. If you don’t advocate for what you believe in, then someone else will advocate for something that you might not like. There are many medical student and resident leadership opportunities, both at the state level and national level. You’ll be inspired by others and will have the opportunity to work together to make a difference.

At the convention last year, I was elected as one of the two National Resident Delegates to the AAFP Delegate of Congress. This role taught me the importance of advocacy for myself, my patients, and my collogues. If you don’t advocate for what you believe in, then someone else will advocate for something that you might not like. There are many medical student and resident leadership opportunities, both at the state level and national level. You’ll be inspired by others and will have the opportunity to work together to make a difference.

This year, the conference is from July 28 to 30 in Kansas City, Missouri. There’s a resident bootcamp to help you fine tune your skillset and a storytelling session for students, which can help you tell your story for personal statements. You can register here. I really hope to meet you there! It has changed my life, and I hope it will change yours too!