An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

September 17th, 2010

What Are These Conferences?

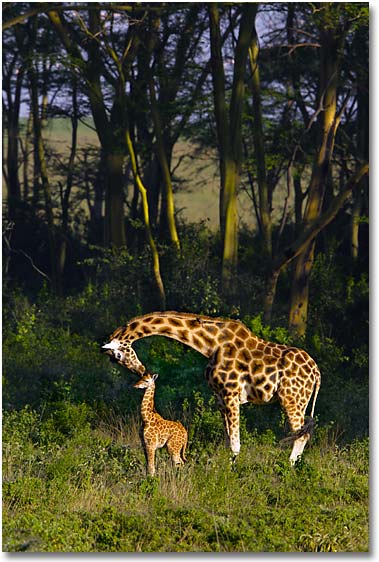

With ICAAC now completed — which took place in a city called Boston but seemed far, far, from home (see picture) — it seems timely to inquire about another form of “scientific” conference.

Every so often, I’ll receive an email like this (slightly edited to protect the sender, whomever he or she may be):

Dear Dr. Professor Sax,

On behalf of the Organizing Committee, I am pleased to invite you to attend the 1st Annual Global Conference on Infectious Disease Pharmacotherapy and Prevention, to be held in [insert economically booming city from Asia or the Middle East here] from 12-15 January, 2011.

We would like you to participate as our guest speaker, giving a keynote address on [insert topic here, likely only vaguely related to what I do] on a day of your choosing.

Already, Nobel laureate Dr. Griffin Doohickey [I made that name up] has agreed to chair the meeting. If you decide to participate, you will be joining several other internationally-recognized leaders in research who will be providing plenary lectures as well.

I’ll admit that the first time I received one of these, I was extremely flattered — after all, who wouldn’t want to visit Dubai, or Beijing, or Taipei?

I’ll admit that the first time I received one of these, I was extremely flattered — after all, who wouldn’t want to visit Dubai, or Beijing, or Taipei?

But since none of these invitations actually offered to cover the expense of travel, accommodation, or registration, I became suspicious — could it be that most (if not all) of these meetings are bogus, designed to separate academics from their money by appealing to their professional narcisism?

If I’m right, I sure hope Dr. Griffin Doohickey hasn’t provided the organizers his credit card or bank account information. And if he has, there’s a Nigerian prince I’ve heard from who has a very promising investment opportunity.

September 6th, 2010

Treating Cellulitis: Getting the Answer Wrong and Right

What’s the right antibiotic choice for cellulitis in the era of community-acquired MRSA?

What’s the right antibiotic choice for cellulitis in the era of community-acquired MRSA?

As astutely pointed out by Anne in her comment, the “correct” answer to the recertification question was #4, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, for the following reason:

I am not a doctor, I am a test developer. Having exactly zero knowledge about the content here (could be Chinese to me), but based solely on the structural design of multiple-choice items, I would venture to guess that the correct answer (the “key” in testing parlance) is #4. I say this merely because it is significantly longer than the other three options (the “distractors”) and therefore leads one to believe that it contains the best information.

However, what does it mean that the person giving the correct answer isn’t a doctor, and admittedly has “zero knowledge” on the subject?

Well, it probably means that the question is flawed — which is obviously the case, since there’s no right answer.

Azithromycin is plainly wrong.

You migh choose dicloxacilln or cephalexin, but one over the other? And both don’t cover MRSA.

And trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole doesn’t cover strep.

Don’t believe me? Read this recent paper on community acquired “nonculturable” cellulitis, which shows that a significant proportion are not surprisingly still due to beta strep, even in the era of community acquired MRSA.

In the real world of treating patients and not answering test questions, what we actually should do in this situation is hardly clear — diclox or cephalexin first then change if no response? TMP-SMX + amox?

I’d suggest that such ambiguous situations make for exam items that are more maddening than educational.

September 1st, 2010

Testing your Testing Skills

Have I whined yet about how I’m part of the first Internal Medicine class that was not “grandfathered” through to eternal board certfication?

Have I whined yet about how I’m part of the first Internal Medicine class that was not “grandfathered” through to eternal board certfication?

If not, now I have.

So for you fellow test-takers, here’s another one for you, adapted somewhat from this delightful experience I’m required to go through every 10 years. Oddly, just like the last one reviewed here, it involves our old friend, MRSA.

18 year old kid scrapes his knee playing a sport, comes in with infection around injury. No purulence. Community MRSA is known to be in the community. What should you give him?

- azithromycin

- cephalexin

- dicloxacillin

- trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

Every so often one encounters a test question that is, frankly, just wrong. But in the often-bizarre world of “let’s pretend” patient care — a test question — you still have to put your money down.

So what’s the answer?

August 30th, 2010

Required Reading: In Love and “Serodiscordant”

Being of a certain age, my wife and I still subscribe to the print version of the Sunday New York Times. Since we also get the local rag, quite a bit of paper is deposited on our doorstep each week.

Being of a certain age, my wife and I still subscribe to the print version of the Sunday New York Times. Since we also get the local rag, quite a bit of paper is deposited on our doorstep each week.

Worth it? You bet, especially since occasionally there’s a gem in there like this week’s Modern Love column. (I supposed we might have stumbled upon it if we’d just read it on line, but I doubt it.) In a piece entitled “On the Precipice, Wings Spread”, Kerri Sandberg writes about dating (and ultimately marrying) her HIV-positive boyfriend:

Even though Theo appeared to fit into the lucky new “long-term non-progressor” category, his H.I.V. status taught us to savor each day because you never know how many you’ll have. We did our best to maintain that balance sexually, too, creating a repertory that was spontaneous without being reckless, careful but not fearful. According to a guy on the Centers for Disease Control hot line, our brand of lesbian-inspired lovemaking posed a “slight risk” of transmission. But I also had a slight risk of dying from just about anything. What was I supposed to do, never leave the house?

HIV clinicians will recognize immediately this bit of denial, one that’s surprisingly common among our “serodiscordant” patients. And even though annual testing is recommended for uninfected sexual partners of people with HIV, those that actually get tested seem to be the exception, not the rule.

But when you think about it further, and when the feelings are described as artfully as Ms. Sandberg did here, maybe that’s not so surprising after all.

August 26th, 2010

Lyme Cases Up — Anecdotes, True Epidemiology, and More Anecdotes

All of us New England-based ID doctors (and internists and family practitioners and pediatricians and NPs/PAs in primary care) who have been in practice a while will tell you that Lyme cases have been increasing for years.

All of us New England-based ID doctors (and internists and family practitioners and pediatricians and NPs/PAs in primary care) who have been in practice a while will tell you that Lyme cases have been increasing for years.

And it’s not just the number of cases, it’s also where and when they are occurring. A few years ago I saw acute Lyme in a man who had hiked near his country house in the Berkshire mountains — in early December. (Yes, it was a warm spell.)

One other memorable case was a woman whose only outdoor exposure was a brief walk through the Fenway Victory Gardens, which are located not 100 yards from Fenway Park — an area hardly known as a hotbed of tick-borne infections.

The funny thing is that the local Brookline Society of Amateur Epidemiologists* has noted that this year Lyme cases seem to be down somewhat, at least compared to the last few seasons. (*My wife and me.) Hence this front page article in the Boston Globe initially took us by surprise.

But the explanation for this apparent contraindication is in the rest of the article, which comments not on this year’s case numbers, but on the trend over the past 10 years — which is exactly what all of us have noted as well.

Lyme disease, the tick-borne ailment once primarily a scourge of the Cape and Islands, is now rampant in swaths of Massachusetts where locally acquired cases were rare a decade ago.

And what about our sense that cases are actually down this year compared to last?

Could be just anecdote — that’s what real epidemiologists are for, to see if this impression is real.

August 18th, 2010

Wednesday Wolbachias

Some scattered HIV/ID issues as the days remain warm but are (sadly) growing shorter:

Some scattered HIV/ID issues as the days remain warm but are (sadly) growing shorter:

- Here’s another one of these legal cases in which a person with HIV is charged with a crime for not warning partners about being HIV positive. Interesting twists this time: it’s a woman, and it’s in Germany. This other one in Texas is more typical. Read Abbie Zuger’s take on all this here from a case in Florida, and my (slightly different) view here.

- Are rates of MRSA really down? Amazingly, astoundingly, shockingly — yes, at least in health care settings. Leading theories for this decline are better prevention efforts for blood stream infections in general and MRSA in particular.

- From what I’ve read about the new “superbug” (blaNDM-1), it seems to be “just” another carbapenemase-producing gram negative … right? Just a hunch, but if it weren’t for this choice part — “Several of the UK source patients had undergone elective, including cosmetic, surgery while visiting India or Pakistan” — this might not have made such a splash in the news.

- One person in New England is sick with Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE), likely contracted before the mosquito spraying began up here. Which reminds me –could there be any advice less heeded than when health departments tell people to wear “long-sleeves, long pants and socks when outdoors” in the summer? Perhaps the one to “avoid outdoor activity at dusk” is a close second.

- Just when you thought the JetBlue flight attendant story could not get more bizarre — well yes it could.

- Not an ID-related factoid, but this information about head trauma mimicking ALS is incredibly interesting. Confession: Gehrig’s “Luckiest Man” speech chokes me up every time.

Oh, and about the title of today’s entry — read about Wolbachias here (a whole book!) and hat tip to Rob Neyer for the style.

Now I just need a microorganism for every day of the week…

August 10th, 2010

Curbside Consults: The Yin and the Yang

One of the simultaneously most enjoyable and exasperating aspects of being an Infectious Disease specialist is the large volume of “curbside” consultations we get from colleagues.

One of the simultaneously most enjoyable and exasperating aspects of being an Infectious Disease specialist is the large volume of “curbside” consultations we get from colleagues.

For example, here’s this week’s talley — and it’s only Tuesday — done from memory and without systematically keeping track of emails, pages, phone calls, etc.:

- Duration of antibiotics after urosepsis, organism resistant to TMP/SMX and quinolones

- Need for repeat immunizations in splenectomized adults (got that one last week too, coincidentally)

- Work-up for diarrhea and mild eosinophilia in someone just returning from Nigeria

- Best outpatient antibiotic for prevention of MRSA recurrence

- Interpretation of Lyme immunoblot

- When to suspect false-positive HIV viral load test

- Can someone catch hepatitis C from sharing a toothbrush? (Very, very unlikely — but why do it, ugh.)

The pluses of doing curbsides are numerous, and extend beyond just helping our colleagues and their patients. It’s also a way of fostering a friendlier clinical environment, one which generates interesting referrals and open communication among different specialties.

After all, lacking a billable procedure (the lucrative gram stain has been outlawed by OSHA years ago), we are hardly going to rake in the dough under the current fee-for-service health care structure regardless. So why not do it?

One potential answer is in this paper just published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, from the ID group at the University of Vermont. They kept track of all curbside consults done in 1 year period, and “converted” them into the work component of the relative value unit, or RVUs.

Not surprisingly, lots of their work is done via curbside:

A total of 1001 curbside consultations were fielded: 66% involved outpatients, and 97% were coded

as initial consultations. A total of 78% of curbside consultations were considered complex in nature, being assigned a CPT code of level 4–5, including 84% of the inpatient and 75% of the outpatient curbside consultations… Curbside consultations represented 17% (2480/14,601) of the clinical work value of the infectious diseases unit. If the infectious diseases unit had performed these curbside consultations as formal consultations, an additional $93,979 in revenue would have been generated.

In other words, time is money — only in this case, time isn’t money at all. The paper concludes by stating:

Hospital administrators, managed care groups, insurance companies, and academic societies need to recognize that curbside consultations represent a large volume of work, are complex in nature, and represent potentially large sources of lost revenue for infectious diseases specialists. The curbside consultation should be incorporated into measures of provider workloads, productivity, contribution to health care delivery, and financial compensation.

Amen to that.

August 3rd, 2010

HIV Testing: NY Makes Progress; Massachusetts … Not So Much

From the office of New York Governor David Paterson:

From the office of New York Governor David Paterson:

The Governor signed into law S.8227/A.11487, which will allow patients to agree to HIV testing as part of a general signed consent to medical care that remains in effect until it is revoked or expires.

The bill will also, among other things: allow oral consent to an HIV test for a “rapid HIV test,” … permit anonymous testing of the blood of a person who is deceased, comatose or otherwise lacks the ability to consent, if someone such as a health care worker is exposed to the person’s blood and no one with the authority to consent to testing can be found in time for the exposed worker to begin medical treatment for HIV.

New York is particularly important for HIV policy in the United States, as it is home to the largest number of people living with AIDS of any state — only California is close.

I particularly like the provision that HIV testing can be done for occupational exposures when the source of the exposure is unable to provide consent. These exposures are a worker safety issue, and the rights of the provider are arguably just as important as the rights of the patient.

As for my home state?

Well the latest HIV testing bill, opined on here, and which looked so promising, just died in the Massachusetts Legislature. Interesting additional coverage of the controversy here on The Huffington Post.

Some debate about casinos got in the way, I guess.

July 30th, 2010

Perinatal Transmission of HIV “Solved” — Now How Do We Pay For It?

Conspicuously absent from this year’s International AIDS Conference were major studies on prevention of maternal-to-child transmission.

Conspicuously absent from this year’s International AIDS Conference were major studies on prevention of maternal-to-child transmission.

It could be that I just missed them, so I emailed a colleague who specializes in the area, and she concurred:

Nope, did not see or hear major PMTCT updates at IAS.

The thing is, this problem has been all but solved, at least scientifically. Put the mom on fully suppressive treatment, and the rest of what is done barely matters — mode of delivery, HIV treatment to the baby, breast vs formula feeding. It’s all a wash, because HIV transmission will barely ever occur.

(Yes, there are numerous other questions unrelated to HIV transmission, most notably the safest regimens from the perspective of in-utero exposure. Bold prediction: one day we will no longer be using zidovudine.)

So — now that we know what to do (treat the moms), we just have to learn how to pay for it. Easier said than done.

July 19th, 2010

Vienna IAS: First (Really) Positive Microbicide Study

Big news from Vienna and Science, imminently:

The CAPRISA 004 trial assessed effectiveness and safety of a 1% vaginal gel formulation of tenofovir, a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor, for the prevention of HIV acquisition in women. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial was conducted comparing tenofovir gel (n = 445) with placebo gel (n = 444) in sexually active, HIV-uninfected 18- to 40-year-old women in urban and rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa … Tenofovir gel reduced HIV acquisition by an estimated 39% overall and by 54% in women with high gel adherence. No increase in the overall adverse event rates was observed. There were no changes in viral load and no tenofovir resistance in HIV seroconverters.

There have been a lot of false starts on this microbicide path, but this one is different — here an actual antiretroviral agent is being used, and, of course, this time it seems actually to work in preventing HIV transmission.

Logistics of drug development, patient acceptibility, applicable populations, cost, long term tolerability and resistance risk, etc. are all huge, but this is very good news regardless.

Full scientific presentation is tomorrow (Tuesday), 1PM Vienna time; full published study available here.