An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

May 6th, 2020

Early Memories of Burton “Bud” Rose, Founder of UpToDate — and Medical Education Visionary

Let’s rewind the clock a bit — OK, a lot. Ancient history.

Let’s rewind the clock a bit — OK, a lot. Ancient history.

It’s winter, 1986. An interview day for medical residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. A bunch of us nervous medical students sit in a conference room, wearing our interview suits, while Dr. Marshall Wolf tells us what to expect that day.

Amazingly, Marshall knows all our names already — which he proves by saying them out loud while handing us each folders.

The folders have our schedule for the day, including our interviews with faculty. One of my interviews is with Dr. Burton “Bud” Rose.

No exaggeration — he was already legendary among medical students. We all had his book, “Clinical Physiology of Acid-Base and Electrolyte Disorders,” which described this complex topic with astonishing clarity.

One of my medical school classmates, a brilliant guy but sometimes a bit of a bull in a china shop, described using this book during his medicine rotation:

His book gave me a rich and logical foundation in the field, along with a silly level of cockiness. The chief resident during my medicine clerkship asked why people with DKA develop hyperkalemia. I responded, confidently, “insulin deficiency and hyperosmolar solvent drag.” She said, “No it is cation exchange.” I replied, “You are wrong.” It went back and forth for awhile, and then I brought her the book next day. I was right, but it did not help my evaluation.

Not surprisingly, I’m awestruck to have an interview with Bud Rose. Even more nervous than before, if that’s possible.

But meeting Bud was great — he couldn’t have been more welcoming. And it was memorable, too — memorable for the precise sentences that made up his conversation (no surprise), and for one particular exchange indelibly imprinted in my memory:

Bud: What area of medicine interests you the most?

Me: Infectious diseases.

Bud: That’s my least favorite. Too much memorization. I prefer areas of medicine where you arrive at diagnoses by understanding basic physiology. (Smiling.) Like nephrology, for example.

Me: Can I change my answer?

Bud (laughing, fortunately): Too late. So convince me — why should someone like ID?

Me: Maybe because I was an English major in college — I like stories. And ID cases often have great stories — like the patient I saw who developed a knee infection from Pasturella multocida because his German shepherd licked between his toes every night. People often think of cats with pasturella, but dogs have it too.

Bud: That is a good story — it’s disgusting, but it’s a good story. But you had to memorize that dogs have pasturella, didn’t you? See, I’m right about ID. Too much memorization.

The conversation then went to his college major, which was History — he liked stories too — and how he ended up in medical school, why he loved teaching, how Boston differs from New York, why I should start playing tennis, and how Brigham medical residents supported each other.

It was a wonderful, far-ranging, and bidirectional conversation. Not intimidating at all.

Not once did he ask me about my less-than-stellar preclinical medical school transcript — relief — and to this day I’m grateful to have matched at the Brigham, no doubt due in some small part to my interview with the legendary Bud Rose.

During residency, he regularly stopped by our intensive care unit to review cases of renal failure and electrolyte abnormalities with us. He’d ask only for the numbers — the electrolytes, renal function, and glucose on a given patient — along with a list of the patient’s medications, and the primary reason for admission to the ICU. That’s it.

From these bare-bones presentations, he’d narrow down the possibilities for each of these cases to the two or three most likely diagnoses — sometimes the only diagnosis. It was a clinical reasoning tour-de-force, the likes of which to this day amazes me.

Let’s now fast forward from 1986 to, roughly, 1993. Yes, still ancient history — still long before the days of high-speed internet.

I’d been gone for a few years doing my ID fellowship, but now I’m back at the Brigham for an ID faculty position. Soon after returning, I get a call from Bud Rose — he wants me to come meet with him to discuss a project he’s working on.

He’s still in the same tucked-away office we had our interview in in 1986, but there’s something new in the room — a small computer on its own little table, barely bigger than the computer itself. I believe it was a Macintosh SE, with a tiny screen and two floppy disk drives.

Here’s our dialogue this time:

Bud: Imagine you’re seeing a patient, and she has hyponatremia. What are the first questions that come to mind?

Me: Hey, I’m an ID doctor — not a nephrologist, remember?

Bud (smiling): I haven’t forgotten that! But this works for anyone who does patient care. What comes to mind?

Me: Hyponatremia — what’s causing it? How serious is it? How do I treat it?

Bud: Exactly! Now if you were planning to manage this patient, you’d want the answers to your questions — normally you’d go to a medical textbook, and find the index, then the chapter on hyponatremia, and then scan for causes and prognosis and management. But what if you could leap right to the answers? And those answers could be updated rapidly with the latest research? Let me show you something.

He heads over to the computer, and launches a program called Hypercard — and writes in the search box, “causes of hyponatremia.” Instantly a paragraph appears on the topic. On the computer screen, I recognize Bud’s clear and well-organized writing, adapted from his textbook.

Bud (continuing): Now look at this — here’s some highlighted text. He moves his mouse over the word “hyperkalemia.” If you click on this word, it takes you to the card on that topic. I call them cards because they represent cards on a particular question, or problem, from my card file.

He points to a meticulously organized card file on which he’s summarized a staggering array of nephrology papers.

Me: Wow, that’s amazing!

Bud: Now I’ve just done this for nephrology. I would like to expand to all of medicine. Are you interested?

Me: Even ID? I thought you hated ID.

Bud: Not if you include the stories.

Of course I’m interested — how cool is that little machine! What he’s showing me in this meeting, of course, is a very early version of UpToDate — the preeminent “point of care” medical reference that has over time all but obliterated traditional medical textbooks.

Bud’s key insight is that what we clinicians want, first and foremost, is authoritative advice on how to manage our patients — and that advice stems from common clinical questions. The background information on pathophysiology, the basic research, the details of clinical trials, the epidemiology should only serve as foundations to this primary goal, answering these questions.

And it must be updated in real-time — no delays for publication of new editions. It isn’t called “UpToDate” for nothing. It anticipated the fast pace of biomedical research long before any other medical resource.

That the original program was distributed on floppy discs makes its success all the more remarkable. He couldn’t have anticipated the ubiquity of high-speed internet, or smart phones, or electronic medical records, but each of these has further solidified UpToDate’s leadership in this medical education space.

Google for medicine, but smarter and based on evidence. What a great analogy.

Bud told me many years ago his two favorite things in the world were taking walks with his wife and kids on a beautiful day, and playing tennis. After that, it was hearing from a clinician that UpToDate had helped improve patient care.

I don’t know how many family walks he took and tennis games he played — but no doubt thousands and thousands have benefited from that project he started on his small computer.

Bud Rose died April 24 2020 of Alzheimer’s disease and COVID-19.

April 27th, 2020

Leaked Remdesivir Study Information, Tocilizumab and Sarilumab Trials, and the Hazards of Early COVID-19 Research Findings

In the podcast I did with Helen Branswell — Infectious Diseases and global health reporter for STAT — she mentioned that the flow of scientific information for the COVID-19 pandemic made the commonly cited “drinking from a fire hose” analogy somehow inadequate.

Since she’s from Canada, I offered Niagara Falls as an alternative, to which she cleverly responded.

Yeah. It’s like standing out at the falls, trying to fill a glass of water. It’s overwhelming and it’s impossible to keep up.

She then mentioned the ascendancy of the preprint servers, which of course is part of this deluge. Never in the history of medical research has so much non–peer-reviewed data made its way to the public’s insatiably hungry (or should I say thirsty, to continue the analogy) view.

And it’s not just preprints. Let’s start with remdesivir, the repurposed antiviral making its way quickly through clinical trials — though apparently not quickly enough.

Here’s what we know as of today, April 27, 2020:

- There is one (count ’em) peer-reviewed published paper on use of remdesivir in COVID-19. It appeared right here in the august pages of the parent journal of this site, the venerable New England Journal of Medicine. It’s an uncontrolled

expanded accesscompassionate use study showing that it might work, and likely isn’t too harmful. That’s all we can say from this controversial publication — controversial because under normal circumstances, the New England Journal of Medicine does not publish studies like this. But they would argue (and I agree), these are far from normal circumstances. - Optimistic comments from a site investigator conducting a remdesivir study became public. During what sounds like a faculty meeting or medical grand rounds, the researcher said people in the study responded promptly to remdesivir treatment. Under ordinary times, this information would not have left the walls of the hospital, or even been mentioned at all — but these are not ordinary times! We conduct all meetings online, making them easy to record (and to leak, um, share). In the annals of “How is current life so bizarrely different from pre-COVID-19 life?,” let’s remember this one.

- Discouraging results of a partially completed study appeared on the World Health Organization’s site. More accurately — briefly appeared; it has now been taken down, but can still be read because someone took a screen shot, and shared it. The target sample size for this randomized trial was intended to be 453, but only 237 enrolled — whether the study was stopped due to a futility analysis or because the incidence of COVID-19 in China fell is not clear (the company statement implies the latter). Regardless, based on this now infamous screen shot, the drug did not significantly improve clinical outcomes. And yes, we’re now gleaning information from a blurry screen shot. Gosh, how we’ve changed.

Published, peer-reviewed data on remdesivir is expected soon — looking forward to that.

Speaking of looking for data, how about this one about tocilizumab, the humanized monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-6 receptor:

#Covid19 | #Tocilizumab improves significantly clinical outcomes of patients with moderate or severe COVID-19 pneumonia. First results of the #CORIMUNO-TOCI open-label randomized controlled trial https://t.co/L403gJ7rfF pic.twitter.com/TLiL8PAmCU

— AP-HP (@APHP) April 27, 2020

That’s all we get — just the title slide of what looks to be a PowerPoint presentation. Someone else offered additional data, perhaps an investigator?

Good news. 129 moderate or severe patients w/ #COVID19. 65 in #tocilizumab arm, 64 in control arm. Endpoint: death or need for mechanical ventilation by D14. Tocilizumab significantly superior to control arm. Publication will follow soon.

Tantalizing! But is there more? Peer-reviewed journal next, or preprint server?

If that’s not enough for a Monday a.m., we also have this announcement about sarilumab, another monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-6 receptor. Here’s an excerpt from what is a quite complex (and confusing, at least to me) summary:

Analysis of clinical outcomes in the Phase 2 trial was exploratory and pre-specified to focus on the “severe” and “critical” groups. In the preliminary Phase 2 analysis, Kevzara [sarilumab] had no notable benefit on clinical outcomes when combining the “severe” and “critical” groups, versus placebo. However, there were negative trends for most outcomes in the “severe” group, while there were positive trends for all outcomes in the “critical” group (see table below).

Got that? Negative and positive trends.

So why is this happening? To overstate the obvious, we are all so desperate for good news on therapy for this terrible infection that we hang on every released word. And the rapidity of communication these days allows such preliminary messages to appear instantly!

But there’s definitely something missing, too. Actually, a lot missing.

Let’s take the tocilizumab study: No details on inclusion or exclusion criteria. No sample size calculation or statistical methods section. Nothing on screen failures. Nothing on dosing, duration of follow-up, concomitant therapies. No “Table 1” of baseline characteristics. No information on clinical outcomes. No safety data.

And of course, no peer review. Oh well.

With sarilumab, we have more information, but it’s so convoluted I don’t think anyone can make an assessment of whether this treatment is helpful, or harmful, or in what populations.

And for remdesivir? One grows tired of getting “critical” medical information from images that probably should have been communicated by Snapchat, if that.

Though come to think of it — what a great analogy. Because nothing ever dies on the internet.

Hey, listen to Helen Branswell tell her story!

April 19th, 2020

Gratitude Before, During, and After Rounding on COVID-19 Service

It snowed in Boston yesterday morning — heavy, wet flakes covered the daffodils and tulips that just started coming up — but this brief return to winter didn’t make my red, itchy eyes from spring pollen feel any better.

The flowers didn’t look too happy either. Oh well.

But just as the annual misery of a typical Boston April started to bug me, the work at the hospital provided plenty of distraction — in a good way. Because even in the midst of this terrible pandemic, there are many reasons for gratitude, some big and some small.

Today’s theme — appreciation for people doing an astounding job under truly difficult circumstances. This is hardly a comprehensive list, but just the things that came to my attention during rounds yesterday.

1. Enter the hospital. In US hospitals now, patients and staff must enter through different doors; at the staff entrance we show our ID badges, then our electronic COVID PASS attesting we’re healthy enough to work, and then we pick up our daily surgical mask. Sounds like a huge pain, right? In fact, the people working at these entrances exemplify kindness and efficiency. Not only that — masks with elastic loops (rather than loose ties) showed up this week back in stock, making life so much easier. Thank you.

2. Pick up your scrubs. Most people caring for patients with COVID-19 wear scrubs, and of course this increased demand strains the scrub distribution system. But so far it’s working out mostly ok, with machines dispensing clean sets in your designated size without much difficulty. I haven’t worn scrubs since residency — a long time ago, yikes — and my amazement at this automated system brought to mind George Bush, Sr.’s clueless response to supermarket price scanners in 1992. In my defense, my last time wearing scrubs was even before this date! Regardless, to the people washing the scrubs and stocking these machines — thank you.

3. Put on your PPE. Even after you’ve done it a bunch of times, it’s not easy putting on this personal protective gear — so many places you can go wrong. Fortunately, observers stationed outside of each room guide us through every step. Marie, Diego, Tommy, Danielle, Lucy (to list 5 of many) — all have been extraordinarily helpful, patient, and responsive, even though this isn’t even close to what they usually do in their actual jobs. They’ve been reassigned from the OR, the emergency room, the surgical floors, or the radiology suites to provide this important service. Thank you.

4. Work in a clean, comfortable place. Hospitals need to be clean, but that’s no easy task. Ever see what the resident work or call rooms look like after lunch? Eek. As we’re cogitating over CRPs and D-dimers and ferritins, the people responsible for keeping our patient floors clean work hard and mostly silently, invariably in the background but very much appreciated. Thank you.

5. Get the update from the nurses. In our “SPU’s” — that’s “Special Pathogen Units”, name not chosen by me — the nurses on the floors have been simply amazing, providing remarkable care under very challenging circumstances. A key thing every ID doctor learns early in his or her training is that if you want the complete picture of how someone is doing, ask the patient’s nurse. They’re the ones in the rooms the most, a reality more true now than ever given the need to preserve PPE and other barriers to patient visits. Thank you.

6. Work with dedicated medical trainees. Medical interns and residents. Surgical versions of the same. ID fellows, dermatology trainees, and budding oncologists. Future cardiologists and invasive gastroenterologists and thoracic surgeons-to-be. One thing you can confidently say about all of them — NONE EXPECTED TO BE DOING THIS RIGHT NOW. (All caps, italicized, and bolded for emphasis.) None signed up for this — not even the ID fellows! All of their planned training has been completely sidelined by a few pangolins (maybe) and SARS-CoV-2. Regardless, the trainees’ sustained calm and pleasant demeanor, their competence, and the compassion with which they approach patient care in the COVID-19 era cannot be overstated. Plus, they want to learn about this scary new disease — no running away, they have genuine interest. Just amazed and impressed. Thank you.

7. Get breakfast, lunch or dinner. By my quick calculations, I estimate that I have eaten 8,423 meals either in our hospital’s cafeteria or the coffee place in the lobby. COVID-19 changed how we get and consume food, but both the cafeteria and coffee place still open daily for business — and all the people working there smile (you can tell by looking at their eyes above their masks), and the food is still fine. And good value! Thank you.

No, things aren’t perfect. The lines for scrubs right before shift changes stretch out into the hallway (6-foot separation!), our elevators in our oldest patient tower still could … be … faster …, there’s no salad bar, and I’ve already complained about the masks with the tricky ties (doing it behind your head is so tough for fumble-fingered non-surgeons).

But boy, things could be worse.

Hey, it reached 60 degrees today! Thanks for that, too.

Mabel and Olive, go at it.

April 12th, 2020

IDSA’s COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Highlight Difficulty of “Don’t Just Do Something, Stand There”

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) gathered a series of experts for what were undoubtedly many late-night calls, reviews of published and pre-print literature, and revisions (of revisions), and admirably generated a set of treatment guidelines for COVID-19.

The problem — there is no proven effective treatment for COVID-19.

That is, there’s no proven treatment based on our usual highest standard metric for efficacy, the randomized clinical trial — nor the next-best thing, a carefully done observational study that meticulously accounts for potential confounders.

Which means these guidelines have a Groundhog Day-like quality. In a series of clear and comprehensive sections, they review the available evidence, then repeatedly conclude the same thing:

The IDSA guideline panel recommends the use of [insert putative COVID-19 treatment here] in the context of a clinical trial. (Knowledge gap.)

Well, not exactly the same thing — for some of these treatments they insert the word “only”, yielding “… only in the context of a clinical trial.”

Here’s the difference between the two, according to the lead author:

For interventions with certainty regarding risks and benefits, the expert panel recommended their use “in the context of a clinical trial”. The guideline panel used “only in the context of a clinical trial” for interventions with higher uncertainty and/or more potential for harm.

But the message is clear. We don’t have sufficient evidence now to recommend any specific treatment.

That’s right — for chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin, tocilizumab, corticosteroids for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), lopinavir/ritonavir — all are readily prescribable by clinicians (each is FDA-approved for other indications), yet none is proven to work for COVID-19.

That might be hard to believe given the publicity surrounding some of the approaches, in particular hydroxychloroquine. But those are the facts as of today.

So where does that put clinicians on the front lines managing this new disease?

Highly conflicted.

Hey #IDTwitter and other clinicians who are caring for people with #COVID19. Have you prescribed (or recommended) hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for this infection? Please vote and comment. Thank you!

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) April 11, 2020

Those favoring the use of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 say that there is at least some evidence that hydroxychloroquine helps — enough so that controlled studies are ongoing. We certainly don’t have anything else to offer, and people are sick!

Plus, there’s a plausible mechanism of action, with in vitro antiviral activity. Maybe even two mechanisms if we consider the anti-inflammatory effect.

In addition, there’s this comment, posted by a critical care specialist in response to my poll:

Yes. No idea if it works, but it’s plausible, and it’s part of the YNHH [Yale New Haven Hospital] treatment algorithm for now. Wonder if those on the only-clinical-trials high horse have ever prescribed Haldol for agitated delirium?

High horse, ivory tower, unconnected to “real practice” — these are common charges levied at academic medicine, with some justification. Certainly not everyone has access to clinical trials.

And even when clinicians do have access to these studies, not all patients meet inclusion criteria, and some others might choose not to participate.

Indeed, at our hospital — which, like many academic medical centers, both has clinical trials for COVID-19 and prides itself on following evidence-based medicine — approximately a third of our COVID-19 cases have received hydroxychloroquine.

(Thanks to our crack ID PharmD Jeff Pearson for the quick data review.)

But why just a third? Why not all of them?

Let’s take up the nay-sayers view. They cite the weakness of the data. One study was, on further scrutiny, so flawed the journal publishing it raised concerns about the low quality of the study. How often do we see that?

Another trial has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal, was quite small, and showed improvement in some minor endpoints only — with tremendous heterogeneity in other treatment approaches.

Furthermore, people already receiving hydroxychloroquine for rheumatologic indications have already acquired COVID-19 — how effective can it be? Plus, there’s an abstract of a study (inadvertently circulated before publication) that not only shows no benefit, but also suggests harm.

If we have questions about clinical benefit, all must acknowledge that any treatment can cause harm. Of particular concern with hydroxychloroquine for elderly patients — those at greatest risk of severe COVID-19 disease — is QT prolongation, a problem worsened with concomitant azithromycin, many other medications, and underlying heart disease.

Is it any wonder the poll results are so split? This is a real tough one.

Often in such circumstances, it’s helpful to ask what one would do for a loved one — or yourself — if having to make the decision.

Personally, I would not take hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19, concerned about side effects and not so sanguine about its potential antiviral activity. The road is littered with drugs that have in vitro activity for respiratory tract infections, and yet do nothing when given to people.

In fact, our list of effective antiviral treatments for these infections is very short! For common respiratory tract infections, we have only the influenza drugs — and even with the flu, some argue the benefits are marginal.

I do understand the opposite view. I would listen carefully to a patient who strongly wanted treatment and go forward with prescribing it, provided they understood the risks and there were no contraindications.

But a well-designed clinical trial? Sign me up. We’ve got to learn more about this disease, and fast.

So take it away, Mabel and Olive. You two are giving me great pleasure at a time when we all really need it.

April 6th, 2020

Dear Nation — A Series of Apologies on COVID-19

(What I’m sincerely hoping we’ll be hearing in an upcoming press conference, and soon.)

(What I’m sincerely hoping we’ll be hearing in an upcoming press conference, and soon.)

Dear Fellow Americans,

I’d like to take a brief moment in today’s press briefing to say something that is long overdue.

I’m sorry.

In a moment, I’ll cite the specifics of what I’ll be apologizing about.

But first, I want to acknowledge the sadness of this spring. I see our parks, fields, and forests coming alive with beautiful flowers and trees in bloom, but see none of the exciting vitality, diversity, and spirit that characterizes our great country.

Here in your nation’s capital, the cherry blossoms bear witness only to a sad silence. I imagine they are in mourning for the terrible losses already inflicted by this cruel virus. No doubt many of you have experienced losses yourself — I offer you my deepest, and most heartfelt condolences in your grief.

Now it’s time for me to apologize. By doing so now, I hope to chart a path forward so we can work together to end this devastating threat.

Let me apologize for dismantling programs put in place to deal with global infectious threats.

Acting like a reality TV host instead of a leader, I fired Tom Bossert — he was Homeland Security Adviser and coordinated the response to pandemics. I also let Tim Ziemer go — he was the head of global health security on the White House’s National Security Council. I then shut down the entire global health security unit.

Then Dr. Luciana Borio, the National Security Council’s director for medical and biodefense preparedness, left as well. Like Ziemer and Bossert, my administration never replaced these talented individuals — I confess these moves greatly weakened our ability to respond to infectious threats.

Dr. Borio tried to warn us in late January what was coming. I’m sorry for not heeding that warning.

I also apologize to the reporter who asked me about these actions, and I called her questions “nasty” — that was an inappropriate and disrespectful response. You were correct to challenge me on these moves, as have many others in these exchanges. Going forward, I promise to engage in productive dialogue with an understandably interested press corp.

I have repeatedly proposed funding cuts to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), where many positions also remain unfilled. I even did this after COVID-19 had already appeared in our country. I’m sorry about that.

In addition, I have taken away the CDC’s lead role in navigating and monitoring a response to the outbreak, silencing their regular briefs during infectious threats. The CDC workers are dedicated public health professionals who deserve our respect, and our thanks. They tried to issue a broad warning in late February, one we should have heeded.

Instead, I downplayed their warnings. I’m sorry to them, and to you, for this misdirection.

I apologize for all the times I’ve mentioned that media coverage of COVID-19 is politically motivated. Such comments only serve to drive us further apart at a time when we need to be working together.

In other words, from now on, no more of this:

Low Ratings Fake News MSDNC (Comcast) & @CNN are doing everything possible to make the Caronavirus look as bad as possible, including panicking markets, if possible. Likewise their incompetent Do Nothing Democrat comrades are all talk, no action. USA in great shape! @CDCgov…..

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 26, 2020

I’m sorry for not accepting the WHO COVID-19 test when first offered to the United States, for not moving more quickly to remedy our initially flawed tests, and for the ongoing struggles you experience even today with testing.

I did not help matters by saying in mid-March that COVID-19 testing could be obtained easily by any doctor, and that the tests were perfect. This clearly misled the public, causing more confusion — I apologize for that.

I’m sorry for calling the virus that causes COVID-19, which is SARS-CoV-2, the “Chinese virus”. Such medically inaccurate comments only encourage racism.

I’m sorry for saying to those working at overrun and beleaguered hospitals that they are exaggerating their need for lifesaving equipment such as ventilators. To the Governor of New York, I admire the selfless leadership you are displaying as our country’s largest city grapples with this terrible health threat.

To those of you on the front lines, putting your health and your family’s health at risk to care for people with COVID-19, I apologize for not doing enough to protect you. Despite what you have heard from our administration thus far, the federal stockpile should be there for all of us.

I also am sorry for the patchwork system in place for distributing these materials, which does not appear to be equitable.

Moreover, I apologize for implying that we already have an effective treatment for COVID-19, when such statements need the support of carefully done clinical studies.

Mostly, I’m sorry for the lies, half-truths, impulsive attacks, and bullying I’ve been responsible for ever since this horrible pandemic spread around the world. At times I confess financial and market forces, along with politics, motivated my actions more than personal and public health. I deeply apologize for that.

Many, including myself, have said we’re at war right now. Indeed, some aspects of this struggle are similar to war, when all a nation’s resources must be mobilized against a common enemy.

But wars pit people against people, so the comparison doesn’t quite fit, especially in a time when human kindness and caring are so important. In the fight against this infection, it isn’t other people who are enemies — it’s the virus.

Let’s work together to fight it.

Thank you.

(This song was co-written by Adam Schlesinger, who died last week of COVID-19 at age 52.)

March 26th, 2020

No Opening Day … Yet

My memories of spring have always included baseball.

I worshiped my older brother Ben — he’s still pretty great — and he loved baseball. So as the days in March shifted from cold and dark to slightly less cold and much less dark, the game he played so brilliantly with his friends pulled me in. I was hooked.

I became so obsessed with baseball that my mother recalls hearing me talk about it in lengthy, excruciating detail — our “conversations” became tedious enough that she would intermittently say “yes” or “mmm” or “wow” just to pretend she was actually listening.

(Mom, all is forgiven.)

When the warm weather truly kicked in, I played various pick-up games pretty much every day — stickball, fungo, softball, Whiffle ball, some rubber-covered indestructible ball that had the same size and weight as a baseball, but survived concrete and pavement. We made up rules since we never had full teams.

No hitting to right field. No walks. No base running — played with “imaginary” runners on base. A cleanly-fielded grounder was an out since no one played first. A ball in the trees was a home run. Over the trees was a Grand Slam, even if no one was on base.

The rectangle-shaped strike zone painted on the school brick wall would have to suffice for every player — didn’t matter if you were Jose Altuve- or Aaron Judge-sized.

Also, there was Little League, then baseball for my school teams. Take a look at that keystone combo in the photo!

Meanwhile, I read everything I could about the sport — its rich history, the great players and the teams, the remarkable games, the endless statistics. A memorable (to me) 4th grade class presentation on Ty Cobb consisted of my listing, with astonishment, his stratospheric batting averages each year:

“… .382, .419, .409, .389 … .383, .382, .384 … .389, .401!”

Now that was an exciting report. One of my classmates bluntly told me afterwards she’d never heard anything so boring in her life.

Today was supposed to be Opening Day for the 2020 baseball season.

But COVID-19 had other ideas, halting Spring Training and delaying the start of the season until who knows when.

“You don’t make the timeline, the virus makes the timeline,” says the wise Dr. Fauci. This version of how long we’ll be dealing with COVID-19 strikes me as much more grounded in science than Mark Cuban’s.

As a result, while usually we cue up this brilliant passage about baseball from Bart Giamatti at the end of the season, how about now?

It breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart. The game begins in the spring, when everything else begins again, and it blossoms in the summer, filling the afternoons and evenings, and then as soon as the chill rains come, it stops and leaves you to face the fall alone. You count on it, rely on it to buffer the passage of time, to keep the memory of sunshine and high skies alive, and then just when the days are all twilight, when you need it most, it stops.

“Play ball!” can’t come soon enough.

March 22nd, 2020

Quiet Hospital Zone

Academic medical centers right now would provide visitors — if they were permitted — a strange experience.

Academic medical centers right now would provide visitors — if they were permitted — a strange experience.

Usually buzzing with clinical and research activity, with incessant human interactions in hallways, on rounds, at the bedside, in conference rooms, our hospitals are now eerily quiet — and very, very, tense.

Minus the intensive care units, the “special pathogen units” (or whatever name assigned to them), the emergency room — the rest of the place is practically silent.

Elective ambulatory care has basically shut down. Same for elective surgeries.

Scheduled for screening colonoscopy? Cancelled.

Annual mole check with your dermatologist? Rescheduled for 3 months (at least) from now. Hernia repair? Sorry.

Follow-up with your nurse practitioner about that new blood pressure medication? Virtual visit — better get that home blood pressure monitor out from the closet.

The inpatient floors have, as usual, patients with acute medical and surgical problems — but discharges occur expeditiously, with signs at the hospital entrance prohibiting visitors. This is no place anyone wants to linger. The hospital census is way down.

As for conferences, they are all but done. Medical grand rounds, clinical case conferences, morbidity and mortality, resident report — all cancelled, or converted to Zoom, or Webex, or GoToMeeting, or Skype, or whatever your platform may be.

The cafeteria still serves food, but there’s no self-serve anything, a tricky pivot for an enterprise that usually offers many buffet choices. Forget the salad bar. A long-term kitchen employee — Pat, she’s wonderful — wears a mask and kindly hands you your cup of soup, using plastic gloves and plenty of distancing.

No groups congregate at the tables — which are pushed to the side of the room. Don’t sit here.

The cashiers have a wary look on their face — please don’t hand me cash — but to their credit, are as friendly as ever.

Quiet. Hospital Zone.

March 16th, 2020

Difficult Times — Meaning No CROI Really Rapid Review 2020

In a usual year, right about now, I’d be obsessed with two things:

In a usual year, right about now, I’d be obsessed with two things:

- What were the most practice-changing studies presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, or CROI? I’d want to summarize those for a patented, copyright-protected, check-with-my-lawyer-before-copying, Really Rapid Review©®.

- How will the upcoming baseball season play out? Most readers here don’t care, I concede. Oh well, we all have our enthusiasms.

But this isn’t a usual year, especially not for us specialists in Infectious Diseases.

Baseball is on hold for now, thank you coronavirus — they say two weeks, but everyone knows it will be longer. Who knows.

As for CROI? Due to some remarkable sleight of hand, at the last minute it became a virtual meeting, with research and plenaries presented online. The planners moderated the sessions in place right here in Boston — but no one attended live.

I thought about writing a Really Rapid Review©® on this electronic CROI.

But I was so distracted by COVID-19 activities that it was tricky. (Ok. Impossible.) Today I concluded that the product wouldn’t meet the high standards of those who read this site regularly, for which you have my sincere gratitude.

Meanwhile, you can take a look at this isolated citation from the conference. I do think it is the most important practice-changing study from CROI 2020 — how often do we see randomized clinical trials in pregnant women with HIV?

(HARDLY EVER. There, I answered.)

It’s called IMPAACT 2010. And with the disclosure that I’m a (relatively unimportant) co-investigator on the study, and obviously some disappointment that it didn’t get the attention it deserved, here’s a take-home message — DTG + TAF/FTC may well be the best regimen for treatment-naive pregnant women.

Important, practice-changing RCT presented a #CROI2020 on Rx of HIV in pregnancy. Take-homes:

– DTG superior to EFV in viral suppression

– TAF/FTC+DTG best for adverse pregnancy outcomes

– Weight gain most with TAF/FTC+DTG; closest to rec wt changes @IMPAACTNetwork pic.twitter.com/6mNWstFbVX— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) March 11, 2020

Meanwhile, if you want to know how your fellow ID doc feels right now, take it away Adi:

Medical professionals internally right now pic.twitter.com/vYlABMUycv

— Adi (@IDdocAdi) March 16, 2020

Thank you for your patience. And take care of yourself during this difficult time.

March 8th, 2020

As Testing Ramps Up, Diagnoses of Coronavirus Disease in the U.S. Will Soon Increase Substantially — How Will We Respond?

Brace yourself. As coronavirus disease (COVID-19) occurs at multiple locations around the United States, the number of confirmed cases here is about to increase big time.

There are two reasons:

- New infections

- More testing

Believe it or not, despite statements by certain politicians, COVID-19 tests still cannot be ordered by any clinician who believes it should be done. In many parts of the country — including, as of today, Massachusetts — a local health department continues to be the only place to get the test. These state labs have limited resources, and hence must offer the test only to those who have a clear exposure, or have a severe respiratory illness without other obvious cause.

That’s about to change. Two of the largest commercial labs in the country, LabCorp and Quest, announced that they have tests ready to go.

Plus, multiple academic medical centers plan to modify their existing molecular diagnostic assays by adding the coronavirus genetic sequence as a target. This will enable testing to be done rapidly “in house” at hospitals that see the highest volume of critically ill and immunocompromised patients.

And not a moment too soon. By all objective measures, our testing has been woefully inadequate, meaning that the reported number of diagnosed COVID-19 cases are the proverbial tip of the iceberg — an iceberg of the pre-climate change magnitude.

Consider — today’s report shows 484 cases reported with 20 deaths. Remember that these tests were done mostly on the sickest people. That’s why our mortality rate is so high at 4.1%.

By contrast, consider South Korea, which already has widespread disease and an aggressive testing policy (they have apparently done over 140,000 tests). They have diagnosed 7,314 COVID-19 cases, with 50 deaths, for an estimated mortality rate of 0.6%.

If we apply that 0.6% mortality rate to the 20 deaths we’ve had here, this would mean there are already around 3,000 cases in the United States. We just haven’t been testing enough to find them.

(Apologies to epidemiologists for the crude estimates. Hey, math is hard.)

There are several ways we could — as clinicians, scientists, media, public — react to this surge of cases that will inevitably dominate the headlines in the coming weeks.

On the negative side is panic, which will bring with it further hoarding behavior, conspiracy theories, and unproductive accusations. On this last one, I’d like to emphasize what I posted here about the people I know who work at CDC and the department of public health — they are not to blame:

Agree. The people I know who have worked at @CDCgov and at @MassDPH have been hard-working, mission-driven, and science-based individuals who want to do the right thing. They must be given the resources they need. https://t.co/iukkqLkRMb

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) March 7, 2020

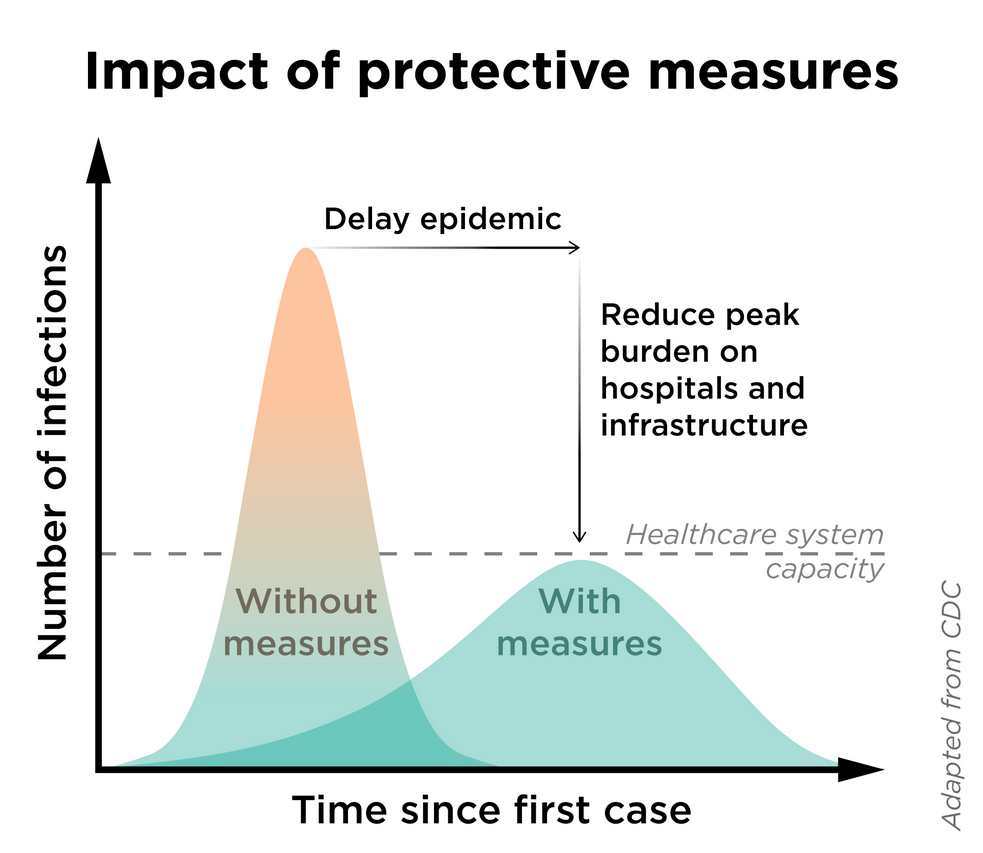

Another terrible reaction will be to suppress the information.“I like the numbers being where they are” is not an effective mitigation strategy — a strategy which will be critical to prevent the overburdening our healthcare system (see figure).

What I’m hoping for?

Let’s welcome the accurate data, even though the numbers will sound scary. It’s time for expansive tests for COVID-19, even introducing them as soon as possible on our multiplex respiratory virus testing platforms.

Such information will give us a much better sense of the spectrum of the illness here, as well as the risk factors both for COVID-19 acquisition and severe disease. It will also allow us to institute more sensible infection control policies, to allocate resources where the disease is most prevalent, and to construct viable strategies to turn the tide against the epidemic.

When Knowledge is Power confronts Ignorance is Bliss during a public health emergency, give us the first one every time.

March 6th, 2020

CROI 2020 Will Be a “Virtual Meeting” After All — Plus, What Scares Me (and Doesn’t) About Coronavirus

This just in:

BREAKING NEWS: #CROI2020 will be a virtual meeting this year! Thanks to @IAS_USA @DonnaJacobsen and all CROI leadership for wrestling with this difficult decision and putting public health first. https://t.co/KPmJ66x7GL

— Melanie Thompson (@drmt) March 6, 2020

If you’re a frequent reader of this blog, you might have read here just minutes ago that it was going ahead after all — with a discussion about how difficult it must have been for the organizers to make the decision.

Never mind. Kudos to all of them for remaining nimble in this uncertain time.

As for the coronavirus situation, there are some things I truly fear — and others, not so much.

I was asked to write about them on WBUR’s CommonHealth. Many thanks to Carey Goldberg for this idea, and coming up with the excellent title.