An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

February 25th, 2020

First Week on Service, with One-a-Day ID Learning Units

There is almost always something to be learned from every new patient.

There is almost always something to be learned from every new patient.

It might be buried somewhere in the history, or the physical, or the lab tests, or the micro, or the imaging — but the odds are excellent that, with enough rumination, you’ll find it.

I can’t remember now who taught me this important fact, or even if it was ever explicitly stated to me. Quite possibly it was just implied — or personified in action — by some really smart, impressive clinical mentor. Someone skilled in finding that nugget of learning in every case.

It might have been my legendary residency program director; or the World’s Greatest Chief Medical Resident (I’m still missing her, sadly); or the brilliant Chief of ID during my fellowship; or the most intuitive ID clinician on the planet.

(FYI, that last guy remains an invaluable resource on tough cases.)

Regardless, these ID Learning Units are out there. And here are seven — one-a-day — from my first week on the inpatient ID consult service:

1. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis. You’ll have an “a-ha” moment the first time you see this strange and challenging entity.

Day #1: Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis (CNGM) is a chronic inflammatory process, associated with corynebacterium spp. (Causal?) Optimal management remains unclear–generally involves combination of abx and corticosteroids. @Yijia_89 https://t.co/RjeerNHSb6

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 19, 2020

2. Consider pulmonary arteriovenous malformations when encountering a brain abscess, especially if there are no other obvious risk factors.

Day #2: Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations are a risk factor for bacterial brain abscess; some have a history of recurrent nosebleeds, with visible mucocutaneous telangiectasias on exam. Suggests all brain abscess pts should be screened for PAVM. https://t.co/KAtOECbJOn

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 20, 2020

3. Chronic meningitis — must be one of the most difficult diagnoses in all of ID.

Day #3: Chronic meningitis is CSF pleocytosis that persists for at least 4 wks without spontaneous resolution. ID, autoimmune, and neoplastic processes may be causative; up to 30% no Dx. Next gen sequencing may help. @Yijia_89 @rose_m_olson https://t.co/ZAbUMFOljW

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 21, 2020

4. A convenient cefazolin dosing strategy in hemodialysis — thanks to Dr. Chris Bland, who pointed out this even better study. A real game-changer for inpatient ID consult services everywhere.

Day #4: Cefazolin dosed post-hemodialysis is an ideal strategy for treating MSSA infections in patients with ESRD, obviating the need for a PICC line or other catheter. Excellent PK; good outcome in this small clinical study of bacteremia. https://t.co/nfRca4S49t

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 22, 2020

5. With cutaneous lesions that may be zoster, PCR is the diagnostic test of choice — much better than both culture (which lacks sensitivity) and direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) testing, which is highly dependent on getting enough cells.

Day #5: PCR is the diagnostic test of choice for cutaneous VZV, greatly surpassing viral culture in sensitivity (and also much less operator dependent than DFA). Of course in many cases, clinical diagnosis is sufficient! https://t.co/pt3z80fecA

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 23, 2020

6. You know those patients with a positive syphilis screening test, a positive confirmatory test, but a negative RPR? Well, as we’ve discussed before, they’re quite unlikely to have neurosyphilis.

Day #6: In a study of 265 CSF exams, not a single case of neurosyphilis was diagnosed among those whose blood VDRL was negative. Similar study from Hopkins with RPR. h/t Khalil Ghanem https://t.co/lkyu3sNiKL pic.twitter.com/ptk0ScztFy

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 24, 2020

7. When scanning your HIV patient’s historical genotypes, if you find Y188L, that eliminates the entire NNRTI class of drugs. It’s also naturally present in all HIV-2 isolates.

Day #7: Universal resistance of HIV-2 to NNRTIs is due to the Y188L polymorphism, which appears in all HIV-2 isolates. (Similarly, when seen in HIV-1, Y188L confers resistance to all NNRTIs, including doravirine, +/- etravirine.) @Yijia_89 https://t.co/tpeGG1Upgn

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 25, 2020

February 17th, 2020

Short-Course Treatment of Latent TB, Combination Therapy for Staph Bacteremia, Adult Vaccine Guidelines, Novel Antifungals, and Others — A Non-COVID-19 ID Link-o-Rama

There’s so much out there right now on COVID-19 (the disease) and SARS-CoV-2 (the virus) that the other ID news gets crowded out.

Which means it’s time for non-COVID-19 ID/HIV Link-o-Rama! I haven’t done one of these in a while, so there’s plenty of material in the vaults yearning to be free.

- The CDC now recommends short-course, rifamycin-based, 3- or 4-month latent TB infection treatments as preferred over 9 months of isoniazid. Completely agree, as 3 or 4 months seems so much shorter than 9 months. Important reminder — watch for rifampin-related drug interactions! Will the 1 month of rifapentine plus isoniazid regimen be in the next version of these guidelines?

- Among patients with MRSA bacteremia, addition of an antistaphylococcal β-lactam to standard antibiotic therapy with vancomycin or daptomycin did not overall improve outcomes. While persistent bacteremia was numerically reduced with combination therapy, vancomycin plus an antistaphylococcal penicillin led to a higher rate of renal injury, prompting the DSMB to stop the study early. This safety issue was not observed with cefazolin, so vancomycin plus cefazolin is still being studied in a separate trial. Excellent summary from the lead author Steven Tong here.

- Ceftaroline plus daptomycin combination therapy may reduce mortality in patients with MRSA bacteremia. This retrospective, matched cohort study supplements favorable findings on this combination from an earlier, small, randomized trial. Some appropriately cautionary commentary from the lead author Erin McReary here. Unfortunately, it does not appear that a randomized study of this combination is in the works due to the cost of the drugs and lack of interest from the manufacturers. Let’s continue the staph bacteremia theme but move on to MSSA with …

- Cefazolin and ertapenem appear to rapidly clear persistent MSSA bacteremia. This uncontrolled study describes 11 patients for whom this combination treatment quickly cleared blood cultures. The authors postulate that ertapenem “rescues” the relatively attenuated activity of cefazolin against MSSA, noting that certain microenvironments (such as bacterial endocarditis vegetations) might make this reduced activity clinically relevant. That’s enough Staph bacteremia for now!

- The latest DHHS HIV guidelines have added dolutegravir (DTG) plus lamivudine (3TC) as a recommended initial regimen. This is the first time a two-drug regimen has garnered this status. Appropriately, there is accompanying cautionary language about excluding baseline HIV RNA > 500,000, chronic hepatitis B, and transmitted M184V. With the encouraging data on this highly effective two-drug regimen, I ask — what’s the purpose of abacavir/3TC/DTG, which is also still listed?

- The TANGO study showed that people with viral suppression on tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)-based treatments can safely switch to DTG/3TC. Switch strategies will likey account for most of the use of this DTG/3TC regimen, since for initial treatment, it’s still easier to go with TAF/FTC/BIC or TAF/FTC plus DTG (no need to know baseline viral load, resistance, or hepatitis B status). And another dance-named study — SALSA — will expand this switch population to anyone who doesn’t have resistance to either 3TC or DTG (no baseline TAF regimen required). No reason why the results of SALSA will be any different than TANGO, but of course surprising things do happen. And no, I don’t know what either of these acronyms stands for.

- The cost of antiretroviral therapy in the United States is high — and increasing faster than the rate of inflation. In 2012, the yearly average wholesale price for recommended initial regimens was $25,000 to $35,000, increasing to $36,000 to $48,000 in 2018. While hardly anyone pays this full price due to insurance, the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP), patient assistance programs, and other funding mechanisms, even paying part represents real hardship for some patients — especially concerning since high out-of-pocket costs negatively impact adherence.

- Immunization for zoster may reduce the risk of stroke. In a review of Medicare data, receipt of the live zoster vaccine was associated with a 20% reduction in the risk of stroke for those younger than 80. Note that the data analyzed preceded the availability of the recombinant zoster vaccine, which is more effective in preventing shingles than the live version. Since zoster is a potential trigger of stroke, would we see an even greater decline in stroke incidence with the newer vaccine? A compelling additional motivation for immunization.

- Roughly $42 million was spent responding to measles outbreaks in 2019 alone. In addition to the huge cost of controlling these outbreaks, there is also the opportunity cost for public health departments and their staff — who have plenty of other work to do. So annoying.

- Another state has a bill to eliminate “religious” exemptions for vaccines. Strongly support these bills! These non-medical exemptions for children are particularly insidious, as clinicians out of respect may not want to question patient preferences based on religious beliefs. But the reality is that no mainstream religion actually prohibits vaccinations, which is why I put “religious” in quotes.

- The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) released its 2020 Adult Immunization Schedule. As anticipated, they formally endorse some changes hinted at previously — notably no longer recommending pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV-13) for all adults older than 65 (“consider” based on preference), and supporting the HPV vaccine up to age 45 if patients have ongoing risk for new infection.

- Approximately 8% of mycoplasma isolates in the United States have evidence of resistance to macrolides. Difficult to estimate the clinical implications of this resistance, since we rarely isolate mycoplasma in clinical practice and such testing is only available in research laboratories. Regardless, fluoroquinolones and doxycycline likely retain activity, along with the recently approved drug lefamulin — an antibiotic I still haven’t had the opportunity (or cause) to use.

- Here’s a mega-review of investigational antifungal agents. Rezafungin, ibrexafungerp, olorofim, fosmanogepix, et. al. — the gang’s all here! An incredibly useful paper, especially for those of us not actively involved in antifungal research.

- In a retrospective, multicenter, cohort study done in the VA system, empiric anti-MRSA therapy for patients hospitalized for pneumonia was associated with worse clinical outcomes — even in those at risk for MRSA. By using some serious statistical gymnastics, the investigators examined data from 89,000 admissions to emulate a clinical trial result. Can you say “inverse probability of treatment–weighted propensity score analysis using generalized estimating equation regression” and explain it, please? Still, it’s another cautionary note about unnecessary broad-spectrum therapy and a real boost to antimicrobial stewardship efforts to stop empiric vancomycin.

- Dr. Aditya Shah, an ID Fellow at Mayo Clinic, continues to make us laugh. How about this one from last week?

When the attending supervises the procedure you are doing #stewardmeme https://t.co/WqEIaJ2W8O

— Adi (@IDdocAdi) February 16, 2020

Adi was kind enough to join me on an OFID podcast to discuss what motivates and inspires him to post these memes — highly recommended!

February 9th, 2020

Should Medical Subspecialists Attend on the General Medical Service?

As I’ve written about many times on this site, one of the highlights of the year for me is when I attend on the medical service — something I’ve been doing pretty much forever.

As I’ve written about many times on this site, one of the highlights of the year for me is when I attend on the medical service — something I’ve been doing pretty much forever.

There’s a wonderful learning exchange that goes on, with my knowledge of ID being repaid in kind by the others on the team — interns, residents, nurses, pharmacists, other attendings — who bring me up to date on current general medicine outside of ID.

(Including the acronyms. Yikes!)

I tried to capture this flow of information by commenting on this highly amusing post by Mayo Clinic’s Dr. Adi Shah — and hence confess was taken aback by this comment from Dr. Stephen Shafran, an ID doctor from Canada:

https://twitter.com/ShafranStephen/status/1215526965697896449?s=20

This is an important perspective, one which we subspecialists should examine carefully. How can we ensure that the care and supervision we provide be as safe as that done by a generalist?

This concern has been on my mind the past few weeks, prompting posting of this poll:

Hey #medtwitter, picking up on a classic @IDdocAdi meme from earlier this year, I ask this question — is it ok for medical subspecialists to attend on a general medical service? Why or why not?

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 8, 2020

While the results are reassuring, this is hardly scientific — clearly many of the people who participated are ID specialists themselves, and probably many of them also attend on general medicine.

So, where are there actual data? I searched for studies on clinical outcomes for generalist versus subspecialist inpatient attending — and came up with very little.

One study from a single academic medical center suggested that hospitalists had more efficient use of resources (shorter length of stay and costs) than rheumatologists and endocrinologists, but clinical outcomes (readmissions, mortality) were similar. So, is it really unsafe?

As for the trainee experience, this group from UCSF argued strongly that having subspecialists as medical attendings greatly enriches their learning, and might motivate residents to pursue a given subspecialty as a career.

In the absence of definitive information, allow me to list certain strategies that I hope mitigate the safety issues Dr. Shafran raises.

- Those of us subspecialists who choose to do inpatient medicine generally maintain certification in Internal Medicine as well as our specialty.

- It’s very much a self-selected population of subspecialists who choose to do general medicine.

- The subspecialists well-represented on general medicine services have, in their day-to-day activities, a substantial amount of general medicine in their practice — both inpatient and outpatient. There’s a reason you won’t see many subspecialist attendings on medicine who spend most of their time inserting coronary stents or doing ERCPs.

- Obtaining consults on cases outside of one’s comfort zone is encouraged, and never considered a sign of weakness.

One other thing, perhaps specific to our hospital, is the structure of our medical team. The rotations typically pair us subspecialists with hospitalists or outpatient generalists. While only one doctor can be the attending of record for a given patient, the team has two attendings, both hearing about all cases on rounds. More on this team structure here.

After the above exchange occurred on Twitter, I received the following kind email from Dr. Badar Patel, one of our interns:

The experience I’ve had with subspecialists serving as our general medical attendings have all been extremely positive, and I don’t believe we’ve had safety issues as the Twitter thread would suggest. I am interested in medical education and would love to be involved if an opportunity to study this in a formal manner were to come up.

For a start, he’s created a survey about this issue, and already sent it to our house staff.

If you’re in clinical medicine, we’d be thrilled if you would take it as well — here’s the link. All responses are anonymous. We plan to write up the results in a future perspective piece.

And who knows, maybe we’ll learn something! After all, we all have the same goals — better care for our patients, and a better learning experience for our trainees.

Thoughts, comments, and opinions on this topic most welcome!

February 2nd, 2020

A Coronavirus ID Link-o-Rama, Because I’m Not Watching the Super Bowl

With so much of the ID-related news out there dominated by the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV, hard to type) outbreak, it seems appropriate to collect some of the more interesting or useful findings in this busy past week.

With so much of the ID-related news out there dominated by the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV, hard to type) outbreak, it seems appropriate to collect some of the more interesting or useful findings in this busy past week.

Think of it as an ID Link-o-Rama — Special Novel Coronavirus Edition.

As with last week’s post, an important caveat — the outbreak continues to evolve rapidly, and data quickly become out of date. All are encouraged to check in with the excellent guidance and information on the CDC, WHO, and IDSA sites (among others), all of which are updated regularly.

On to the links:

- The mean incubation period of novel coronavirus disease after contact with an active case is around 5 days. The 95% confidence interval around that estimate is 4.1 to 7.0 days. Importantly, the onset of symptoms 2 weeks or more after exposure appears very unlikely. These data should dispel circulating rumors that this virus has a much longer incubation period than other coronaviruses — in fact, it appears quite similar (Figure 3).

- This case cluster demonstrates coronavirus can spread before the onset of symptoms. However, as in most infectious diseases, symptomatic cases are probably more contagious — usually because people with symptoms have a higher viral burden. While the findings in this report are of concern, the true contribution of asymptomatic spread of the virus in the present outbreak remains unknown. [Update: The “asymptomatic” person may have had symptoms after all. Additional details summarized here.]

- The New York Times has posted a widely cited figure comparing mortality and contagiousness of coronavirus with other infectious diseases. Current estimates are 3% mortality and transmission number (R0) between 1.5 and 3.5. It’s an impressive graphic (modeled on this one) that puts the infection into perspective. Importantly, note the log scale of the vertical axis in the Times figure, which prompted this revision:

This is one of those “please don’t judge me for making this horror” graphs that I’ve just thrown together with possibly the least reliable underlying data (hence extensive caveats in caption). All available on github, please scrutinise and send improvements pic.twitter.com/vtU3bUFDzH

— Isaac Florence (@IsaacATFlorence) January 31, 2020

- Here’s a clear explanation why the estimated mortality will likely change — for the better — as we gain greater understanding of the disease. Severe cases tend to dominate reports early in an outbreak; only later, when diagnostic tests and surveillance improves, will we understand how many mild (and even asymptomatic) cases occur. Remember when West Nile virus first appeared in North America? It was initially terrifying — yet we now know that 80% of people who acquire this infection do so without any symptoms whatsoever, and fewer than 1% develop encephalitis.

- Wonderful perspective from Dr. Elizabeth Rosenthal offering her advice on how to avoid coronavirus. Wash your hands frequently. Yep, that’s it — plus a few other things that fall squarely into the “common sense” category. The piece includes interesting anecdotes from when she covered SARS in 2002-3 as a journalist, living in China with her family.

- This online calculator estimates the effectiveness of screening travelers to detect people who have 2019-nCoV. You can move the sliders around on parameters such as incubation period, proportion who have fever, and R0 (transmissibility), among others. Not surprisingly, those most likely to be detected have both fever and a reported epidemiologic risk.

- Some patients with coronavirus disease have already received antiviral therapy with drugs demonstrating in vitro activity against the virus. In this report, a woman received lopinavir/ritonavir (along with oseltamivir). In another case, doctors received permission for compassionate use of the experimental drug remdesivir. Both patients improved — but obviously in these anecdotal cases, we don’t know if they would have improved anyway. A Chinese clinical trials registry cites at least one planned study. My virologist colleague Dr Jonathan Li summarized some of the background data in this thread.

- How did this novel coronavirus first spread to humans? This is critical information — not only for this outbreak, but also for prevention of future zoonotic infections. Excellent summary of ongoing work in this area.

- A pre-print reported that the novel coronavirus had insertions that bore an “uncanny” resemblance to HIV gp120 and Gag. This finding (later withdrawn) triggered a momentary spike in conspiracy theories that would be excellent evidence for the benefits of scientific peer review — which happened in this case anyway, only not in the usual way. For a good takedown, read this analysis.

- Many have tried to put the coronavirus outbreak in perspective by citing this year’s flu season. Here’s the brilliant opening from the linked piece:

The rapidly spreading virus has closed schools in Knoxville, Tenn., cut blood donations to dangerous levels in Cleveland and prompted limits on hospital visitors in Wilson, N.C. More ominously, it has infected as many as 26 million people in the United States in just four months, killing up to 25,000 so far.

In other words, a difficult but not extraordinary flu season in the United States …

So yes — get your flu shot! Listen to Dr. Stephenson!

#Influenza and #coronavirus are the same problem. It’s not a competition over which virus is the scariest. They are circulating at the same time which complicates diagnosis and treatment and add together to stress our health care systems. Flu #vaccine helps *both* outbreaks.

— Katy Stephenson, MD, MPH (@k_stephensonMD) February 1, 2020

As for the title of this post …

Nope.https://t.co/ElJH4KIpvp via @sciam

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 2, 2020

January 26th, 2020

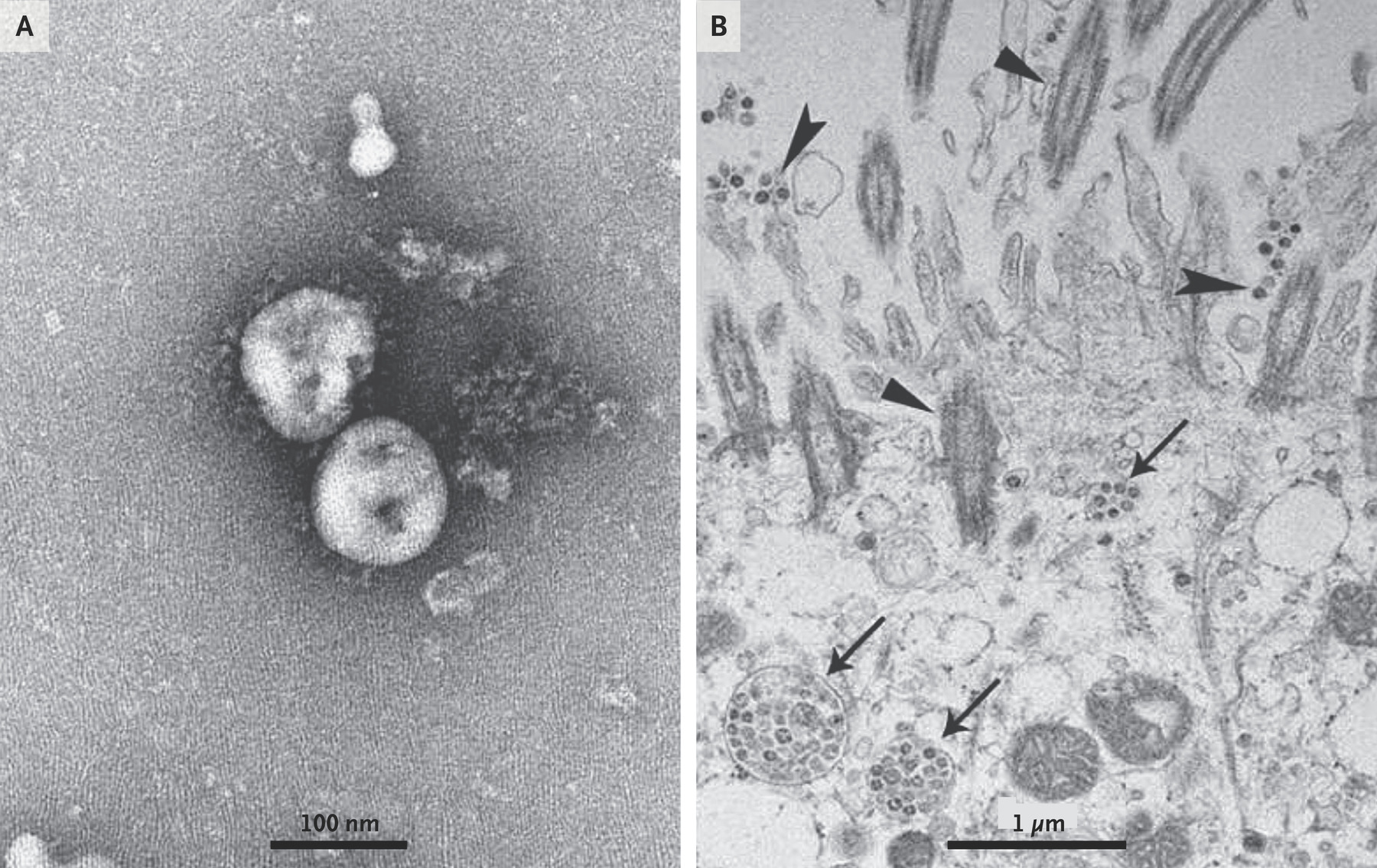

Uncertainties Notwithstanding, Pace of Scientific Discovery in Coronavirus Outbreak Is Breathtakingly, Impressively Fast

The 2019-nCoV, transmission electron microscopy. From The New England Journal of Medicine, January 24, 2020.

The current novel coronavirus outbreak due to 2019-nCoV and SARS from 2002–3 share many features, including:

- Both are coronaviruses, genetically distinct from those that had caused infection in humans previously (most of which led to cold-like illnesses)

- First cases recognized in China, with subsequent international spread

- Source an animal reservoir — likely bats for both of them

- Both cause severe lower respiratory illness

- Documented person-to-person spread, including nosocomial transmission to healthcare workers

What direction 2019-nCoV goes from here remains uncertain, as the current outbreak is rapidly evolving. Despite the extensive press conferences and commentaries from public health officials, microbiologists, and specialists in Infectious Disease — most of them quite thoughtful — the uncertainty will no doubt lead to isolated overstatements of both alarm at one extreme and reassurance at the other.

For a good primer on the current situation, The New England Journal of Medicine and JAMA both weighed in with last week with excellent perspectives.

Uncertainties notwithstanding, I can assuredly say one thing is vastly different this time compared with SARS — the pace of scientific discovery and communication, especially on the molecular level, is breathtakingly fast.

Think about it — less than 2 weeks after the first reported cases (December 31), researchers released the genetic sequence of the virus in its entirety. It’s now available in GenBank.

We already have a diagnostic test being used by our CDC and, internationally, other public health laboratories; this paper describes how such a test might work.

After isolation of the virus, a pre-print demonstrated its affinity for the human ACE2 receptor, which is present predominantly in lower respiratory tract cells. A second scientific group confirmed this finding.

A description of the clinical syndrome can be found here; the incubation period in this family cluster was 3–6 days, though may average 10–14 days; and investigators estimate its contagiousness (R0) — always a dynamic number, especially early in an outbreak — in this report.

Several mention ongoing plans to test drugs with in vitro activity, including approved (lopinavir/ritonavir, interferon) and investigational (remdesivir) agents. Tony Fauci says time from virus discovery to a vaccine in Phase 1 studies could be 3 months — fast!

All of this is quite amazing — and would not have been possible during the SARS outbreak.

Another thing different from 2002 is this was pre-Social Media — which, for all the bad things associated with the specific platform of Twitter, on the plus side it remains an extraordinarily efficient way to transmit and summarize data, at least when it’s done by a thoughtful individual.

Here’s Exhibit A, a must-read thread from Dr. Muge Cevik, an ID doctor in Britain. Thank you!

THREAD

As the #nCoV2019 outbreak continues, a lot of data emerging in real-time & being rapidly disseminated.I compiled the available data (in no particular order) to have a better understanding of #nCoV2019 & will update the list as more info become available. #IDTwitter

— Muge Cevik (@mugecevik) January 25, 2020

Meanwhile, a plea to our media outlets — can we get expert opinion from true experts on viral infections, public health, and policy? Good grief, will Dr. Gwyneth Paltrow be next?

January 20th, 2020

Telemedicine, eConsults, and Other Remote ID Clinical Services Make So Much Sense — Why Isn’t Everyone Doing it?

The ID group at Mayo Clinic just published a small but important study on the use of remote ID telemedicine consults for hospitals that have no ID services on-site.

The ID group at Mayo Clinic just published a small but important study on the use of remote ID telemedicine consults for hospitals that have no ID services on-site.

The consults were “asynchronous”, meaning that the ID consultants at the main hospital finished them within 24 hours — they didn’t have to respond immediately. Importantly, all the institutions shared the same electronic medical record, so the consultants could review notes, lab results, and other tests.

Comparing 100 cases who had “eConsults” with 300 historic controls, the investigators found that the cases with ID eConsults had a substantially better clinical outcome — a 70% (!!!) lower 30-day mortality.

These results didn’t come from some Magic Dust available only to survivors of the bitter cold Minnesota winters — the primary interventions recommended by the consultants included very straightforward (for an ID doctor) advice, such as antibiotic changes, antibiotic duration change, antibiotic deescalation, additional laboratory testing, and consultation with services other than infectious diseases.

The authors acknowledge the important limitations of the study, primarily the fact that the non-randomized design leaves it open to unmeasured confounders influencing the outcome.

Furthermore, since they utilized historical controls, changes in practice could have led to the improved outcomes, not the eConsults themselves.

Still, limitations notwithstanding, let’s imagine the effect isn’t quite this large — it’s still very impressive. As noted by Dr. Saurab Patel, the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval on the reduction in mortality was 30%! People who study health care quality and outcomes would take that any day of the week, thank you very much.

Furthermore, satisfaction among the clinicians ordering the consults was extremely high. Indeed, we find the same thing at our hospital, where we provide eConsults to our primary care clinicians and specialists for non-urgent questions that arise during outpatient care. I attended a meeting of primary care providers on the use of eConsults, and the enthusiasm for this service was off-the-charts high — they love them!

So based on a study like this and our experience, every clinical ID Division in academic medical centers and every ID private practice must be lining up to provide eConsults, telemedicine, or other forms of remote advice, right?

Well, not quite:

Hey #IDTwitter, do you currently do "eConsults" or provide telemedicine services for patients you have never seen for a face-to-face visit? Can be for other clinicians, or directly to patients, or both. Take the poll, then explain why or why not. Thanks!

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) January 19, 2020

Only just over half the respondents do these kinds of consults currently, even though arguably the non-procedural and cognitive-based aspects of ID practice fit perfectly into this remote care model.

In the Discussion section of the paper, the authors cite two major reasons why a substantial fraction of ID doctors don’t do these sort of consultations:

Cost and technical challenges are major barriers to the widespread adoption of telemedicine.

Let’s take the second of these first, the technical challenges.

If you don’t have the same electronic medical record as your consulters, providing this kind of formal consultative service would be difficult, if not impossible. What we ID doctors do best is carefully review the relevant history, laboratory, and imaging data, and make recommendations from synthesizing this information. It’s critical that this review is as reliable as possible — especially since confirming details by talking to the patient may not be possible.

(Reminder: ID doctors take the best histories. Thank you.)

Another challenge is institution-specific credentialing. Even affiliated hospitals in the same healthcare system may have different criteria and systems for credentialing their clinicians. This makes doing a remote consult on inpatients at other facilities far from straightforward — and doing it across state lines might actually be prohibited if the consultant is not licensed in that state.

Now on to the thorniest issue, which is cost. It’s not simply that we’re too busy. If these kinds of clinical services were valued highly enough, we would make time in our schedules to do them, pushing out lower value activities.

In the responses to my poll, the most enthusiastic endorsements of remote consultations come from settings where American-style fee-for-service compensation plays comparably minor role (if that) in a doctor’s salary. Europe, Canada, and here in the U.S., the VA — you get the idea. Says Dr. Ilan Schwartz from Canada:

We cover a catchment area from central Alberta to NW Territories — a geographic area almost 1/3 that of Canada! For some assessments I prefer ability to examine the patient, but for others, telehealth consult is in their best interest. Also sometimes roads are really icy, and if I can spare patients both the inconvenience and the risk of shleping to Edmonton, I will.

No surprise here! What Ilan does in Western Canada makes all kinds of sense, reminiscent of the ECHO research project using telemedicine to treat hepatitis C in remote areas of New Mexico.

But in a differently funded healthcare system — ours — where payment is overwhelmingly based on racking up face-to-face encounters and procedures, the time spent doing eConsults and telemedicine is time not spent in revenue-generating patient care.

And in most practices, eConsults score a big fat zero when it comes to RVUs, that loathsome metric for measuring a U.S. doctor’s “productivity”.

Time for that to change!

Because doing what’s best for patient care should motivate how we spend our clinical time, not racking up RVUs.

January 13th, 2020

Diagnostic Tests for Syphilis Continue to Perplex Even the Experts: An Unanswerable Question in Infectious Diseases

Here’s a tricky clinical scenario:

Here’s a tricky clinical scenario:

- An elderly person with cognitive decline or some other non-specific neurologic symptom sees a clinician.

- Clinician sends a syphilis screen with a T. pallidum enzyme immunoassay (TP-EIA), which returns positive.

- Lab runs a confirmatory test — a T. pallidum particle agglutination test (TP-PA), or similar, which also returns positive.

- The lab then runs a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test, which returns negative.

- There is no known prior clinical or lab history of syphilis exposure, diagnosis, or treatment.

Now what are we supposed to do?

I bring this up because Dr. Thomas Fekete raised just this issue on the IDSA’s ID Exchange message board, generating a spirited discussion.

(I’m citing this discussion and quoting with his permission.)

And every card-carrying ID doctor has been asked what to do in just this setting numerous times since labs started using TP-EIA — and not RPR — for syphilis screening a bit over a decade ago. In one study, this pattern (two positive treponemal tests and a negative RPR) occurred in approximately 3% of individuals undergoing testing.

Here’s why the next step is so controversial: This exact pattern describes three separate clinical scenarios, each of them requiring very different next steps. Here are the potential interpretations:

- The result is consistent with, but not diagnostic of, neurosyphilis. Recommendation: Perform a CSF exam to rule out neurosyphilis. This is hardly a trivial undertaking, especially in the elderly. Further complicating this next step is that the CSF exam is notoriously poor at either ruling in or ruling out neurosyphilis. Plenty of false-positives and false-negatives.

- The result suggests late-latent syphilis with an RPR that has reverted spontaneously to negative. Recommendation: Treat with benzathine penicillin 2.4 million units by intramuscular injection, weekly for 3 doses. In this interpretation, clinicians must consider the likelihood of clinical neurosyphilis to be sufficiently low that this result is unrelated to the neurologic symptoms — which begs the question, why was the test ordered in the first place?

- The result demonstrates prior treated syphilis, with an adequate serologic response. Recommendation: No treatment or further testing necessary. Lots of antibiotics have activity against T. pallidum, so antibiotics administered for other indications over the years have inadvertently provided sufficient treatment.

Let’s add to the quandary by quoting Dr. Fekete on two key points:

I cannot find modern information about the incidence of true tertiary or neurosyphilis in elderly patients with this [testing] profile … These patients would not have come to our attention in the old system for syphilis screening.

Where are the prospective clinical series outlining either actual clinical neurosyphilis — or even CSF abnormalities — in those who have this serologic profile?

Plus, in the pre-TP-EIA era, when we used RPR for screening, neurosyphilis would have been considered “ruled out” unless there was a strong prior probability of this disease (which there hardly ever is).

Sometimes ignorance is bliss!

Want a further wrinkle? Some believe that the recommended treatment for latent syphilis — benzathine penicillin, with its long half-life but low CSF concentrations — adequately treats neurosyphilis as well. The thought here is that the immune system plays a role in clearing the infection, so no need for high CNS concentrations of penicillin — except perhaps in people with immunosuppression, as is seen in untreated HIV.

The data supporting this view (like many other aspects of clinical syphilis) are largely uncontrolled and somewhat dated — but strongly endorsed and frequently cited by advocates nonetheless.

But this position is vociferously challenged by others — again with largely anecdotal and outdated data. This group, now in the majority, inform the current CDC guidelines for treatment of neurosyphilis, which recommend high-dose intravenous penicillin G for 10-14 days — a burdensome treatment not easily (or cheaply!) administered to the elderly, especially those with cognitive impairment.

It’s not as if this neurosyphilis quagmire were a new problem; indeed, the diagnosis of neurosyphilis has been fraught for decades. Often the leading strategy adopted by a hospital or a practice is the one endorsed the most passionately (or most loudly, in case conference) by the local expert or experts.

All this controversy makes this case scenario a classic Unanswerable Question in Infectious Diseases. And perfect for a poll!

So have it at — and educate us by using the comments section to justify your vote.

A 78-year-old man with no known prior history of syphilis or other sexually transmitted infections is evaluated for mild cognitive decline. As part of the work-up, he has the following blood test results: TP-EIA positive, TP-PA positive, RPR negative.

January 6th, 2020

The Decade’s Top 10 Biggest Changes to ID Clinical Practice

Here’s a question for you ID and HIV and other clinicians out there as you start 2020 — what are the 10 biggest changes to ID/HIV clinical practice over the past 10 years?

Here’s a question for you ID and HIV and other clinicians out there as you start 2020 — what are the 10 biggest changes to ID/HIV clinical practice over the past 10 years?

Not necessarily what are the biggest stories or biggest advances (though they certainly are eligible) — but more specifically, when you are seeing patients, what are we doing or seeing or thinking now, in early 2020, that we never could have done in 2010?

You’ll see by reading this list that 10 years is plenty of time for progress — hooray for that. So with the up-front apology that my list inevitably reflects where I practice (USA, New England) and what I focus on academically (HIV), off we go with 10 big changes, one for each year — there obviously could be many more!

#10.

Then (2010): “Vancosyn” or “Vitamin L” (levofloxacin) for everyone? No problem …

Today (2020): Certain antibiotics, once considered quite safe, now have well-recognized severe side effects.

On the inpatient side, there’s now broad agreement that giving vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam together increases the risk of nephrotoxicity. This awareness has led to dramatic reductions in the use of “Vancosyn,” which was all but ubiquitous on medical and surgical services a decade ago. And the toxicities of fluoroquinolones deserve their own brilliant graphic:

Comparing 2010 to 2020 in clinical ID, some very big changes. Here's one — fluoroquinolone toxicity was a known thing, but it wasn't a THING. Others? pic.twitter.com/9WSVvNEmXl

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) January 1, 2020

#9.

Then (2010): Order an HIV test? What a pain.

Today (2020): Written consent for HIV testing no longer required.

In 2010, labs required that formal written consent, signed by the patient, be on file before running an HIV test. This was an actual law in most states! While one might argue that such a policy made sense in the mid-1980s due to fears of discrimination and lack of effective HIV treatments, it was absolutely bonkers (that’s the medical term) in 2010, so many years after we had lifesaving HIV therapy, and were still facing a large proportion of those with HIV undiagnosed. And yes, Massachusetts was the last state to drop this outdated law — not proud about that fact! Fortunately today, a clinician who wants to order an HIV test now just needs to document that the patient verbally agreed to testing — easy peasy. Was that so hard?

#8.

Then (2010): MRSA is taking over!

Today (2020): MRSA is way less common.

If you’d asked me in 2010 to estimate what proportion of our hospital’s Staph aureus isolates would be MRSA in a decade, I’d probably have guessed 75%, or if I was feeling glum that day, 90% — the trend in the early 2000s was just up and up and up for this pesky and difficult-to-treat pathogen, and it was by far the most common microbiologically confirmed cause of skin infections. However, for reasons no one can quite understand, MRSA rates are down everywhere — both in inpatients and outpatients. (Our hospital’s antibiogram now lists MRSA as 27% of Staph aureus isolates.) Not only that, penicillin sensitivity locally among staph is making a comeback, too. No one predicted that.

#7.

Then (2010): Otitis media — antibiotics needed now!

Today (2020): Observation, rather than immediate antibiotics, is now an accepted strategy for certain cases of childhood otitis media.

I put this one in for the pediatricians, especially one particular pediatrician! Although treatment guidelines endorsed observation for otitis media in 2013, apparently only in the past few years have parents grown comfortable with this approach.

#6.

Then (2010): CD4 700? You don’t need to start treatment, let’s monitor blood tests, see what happens.

Today (2020): The “When to Start” debate in HIV therapy ended — everyone should be treated.

In 2010, we might have monitored someone with high CD4 cell counts for a while, allowing them to be viremic for months or even years if they remained asymptomatic. We would never do that today because the START study randomized people with HIV who had no symptoms and high CD4 cell counts to immediate versus deferred therapy, showing a clear clinical benefit for early treatment. Plus, there’s the #2 Big Change listed below as an additional factor favoring treatment.

#5.

Then (2010): Recurrent C. diff? Let’s try another round of vancomycin, maybe with a long taper.

Today (2020): Fecal transplants for relapsing C. difficile colitis are now standard of care.

After a period of initial (and quite understandable) disgust and reluctance from patients and clinicians alike, clinical data on the efficacy of fecal transplants for relapsing C. difficile colitis are now strong enough to give it a place in the most recent treatment guidelines. These clinical trials data have has been strengthened by largely favorable anecdotal experience. While not a panacea — some patients don’t respond, and there are ongoing safety and regulatory issues — the fact that fecal transplant has such a major role in treatment of any condition would have been unfathomable in 2010.

#4.

Then (2010): Worried about acquiring HIV? Make sure you and your partner use condoms.

Today (2020): Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV is an established HIV prevention strategy.

As I’ve mentioned before (and will continue mentioning forever, since it’s in hindsight so bizarre), the first time I heard of this concept was in the 2002 CROI in Seattle, when keynote speaker Bill Gates was asked about people without HIV taking ART to prevent infection. (Why someone was asking the CEO of Microsoft this question is still not clear to me!) His response concisely summarized HIV prevention in that time: “Wouldn’t a condom be easier?” Fast-forward to the IpReX study, the FDA approval of TDF/FTC for PrEP in 2012, several follow-up studies — and today PrEP is broadly endorsed in national guidelines for HIV prevention.

#3.

Then (2010): We have to bring tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment into the 21st century!

Today (2020): TB diagnosis and treatment are both much better.

On the diagnostics side, the The GeneXpert MTB/RIF system has been absolutely transformative, both in high prevalence countries (where it establishes the diagnosis much faster and more reliably than smear), and here as well, where we can rapidly rule out the diagnosis and stop respiratory precautions in low risk cases. Treatment of latent TB now has several shorter options than the old standard of care 9 months of INH. And for multi-drug resistant disease, Dr. Catherine Berry’s comparison says it all!

XDR-TB treatment

2010

“Cat IV” low priority, minimal access

6-7 drugs, daily IM aminoglycoside

2 yrs treatment

Daily vomiting, hearing loss

10 to 20% cure2020

3 to 5 drugs

All oral

6 to 18 months

PN, ON, myelosuppression

?up to 90% cure2022

Watch this space

#2.

Then (2010): The most important thing you can do to protect your partner from acquiring HIV is to always use condoms, even if you’re on treatment.

Today (2020): “Undetectable = Untransmittable” is now a mainstream part of HIV medicine.

Though the prescient Swiss Statement appeared in 2008, it was not until release of the HPTN 052 data in 2011 that this “treatment as prevention” idea gained mainstream acceptance — only to be further supported by the PARTNER and PARTNER2 studies. The bottom line is that we now routinely tell people with HIV that they are not contagious to others if they’re on suppressive HIV therapy. Few (if any) non-Swiss people would have been so bold to say that in 2010.

#1:

Then (2010): Treatment of hepatitis C will be injectable interferon and multiple tablets of ribavirin. Not only that, you’ll need to take it for 12 months, endure many side effects, some of them quite severe — oh, and it will have a 20–30% chance of the treatment working. Sorry about that.

Today (2020): Hepatitis C is cured with 8–12 weeks of well-tolerated, oral treatment in around 99% of people.

I still don’t think we quite appreciate just how miraculous an advance this is, so I’m making it an emphatic #1 biggest change in ID clinical practice. (And Monica Mahoney, PharmD agrees, so it must be right.) As one of my patients said, after having relapsed during interferon treatment twice previously, and finally being cured with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir: “Curing things is good. You doctors should work on more of that.” Agree!

What would be your Top 10? And of course my order won’t be your order, but that’s what the comments section is for!

December 30th, 2019

Welcome to Mandatory Online Module Land!

(What follows is an attempt to derive some humor from those annual online “required learnings” assigned to us each year. Because if you’re in pain, you are not alone!)

(What follows is an attempt to derive some humor from those annual online “required learnings” assigned to us each year. Because if you’re in pain, you are not alone!)

Step right up, Ladies and Gentlemen! Allow me to welcome you to Mandatory Online Module Land — the fantasy theme park Health Professionals around the world can’t stop talking about!

Fire Safety, Natural Disasters, Chemical Spills, Infection Control, Patient Confidentiality, Tornadoes — important topics all! We’ve figured out how to make them into an online, interactive experience that pulses with excitement.

Here, let us share some of the passionate and enthusiastic feedback we’ve received from health professionals at institutions around the country:

Thinking early retirement versus career change right now.

At the end of 16–18hr days, it is really harrowing to get emails telling me that I was “delinquent” on a training module.

34 modules! Took 2.5 hours; 5–10 multiple choices question quizzes per module to “pass.”

Living this misery right now.

So painful those mandatory trainings.

I’m around 3hrs in and still have those 3 annoying “can’t win” modules left …

Ah … the mandatory trainings. The straw that breaks the camel’s back.

I did this for about 3.5 hrs before the whole family came for Christmas— I have several modules left.

I won’t do it unless I get a text from coordinator telling me they might pull me off service.

I would say it takes me 10–15 hrs a year all said and done. And if I am generous, they include about 5–10 minutes of useful information.

Most of them are boring and cover useless information.

Took me FOUR hours and it was worthless: “don’t worry you’ll learn as you go.” Bad for physicians: horrible for patients.

Doesn’t that sound wonderful? Of course it does, and we should know — we created the modules, and are therefore the experts.

We have highly validated studies demonstrating that health care professionals who finish these trainings are better than those who don’t.

Better at what? They’re better at finishing the trainings! Isn’t that enough?

To make a good thing even greater, we’ve added three innovative features to make visiting Mandatory Online Module Land even more fun (as if that were possible).

- We’ve tied completion of the required modules to your earnings. No, we don’t pay you for the time it takes to visit Mandatory Online Module Land and complete the modules. But we do withhold salary for not finishing on time — which, if you think about it, is the same as paying you! Isn’t that generous? Hey, we could have charged you for the privilege of all this learning!

- We’ve given you an few extra days to complete them. You spoke, and we listened. Though visiting Mandatory Online Module Land is fun fun FUN, and the perfect way to spend the holidays, some of you have alternate plans. Some advice: next year, plan ahead and include a visit to Mandatory Online Module Land during that last week of the year! How about that for a New Year’s resolution?

- Certificates! Yes, each completed Mandatory Online Module comes with a Validated Certificate of Completion, suitable for framing, laminating, or some other enshrinement. Display them in your office or exam room! Or print them out and mail to your parents, giving them even more reason to be proud of their highly accomplished offspring!

And for those of you too forgetful to add a trip to Mandatory Online Module Land to your travel itinerary before the due date, we’ve got the reminders down to a science.

Let’s pretend your visits to Mandatory Online Module Land have not yet been completed. We can’t imagine why anyone might delay — what other important things does a Health Professional have to do?

Maybe it’s catching up on your Netflix queue? Editing your videos on TikTok? Some other “worthwhile” (ha ha) pursuit? Hey Doc or Nurse or PA or other Health Professional, lemme tell you — time’s a wastin’! Get back to those modules!

Well no worries — we’ve got you covered! As the due date draws near, through the miracle of computer automation, each day you’ll awake to a personalized, friendly email message from me (whoever I am) — sometimes you’ll get two messages, we care that much!

“Good morning, Health Professional,” these messages will read. “You are delinquent.”

If that’s not supportive, what is?

Apologies for bragging, but I'm the proud owner of a new degree.

Cc'ing @NobelPrize , just in case this was the one missing piece. pic.twitter.com/q5Y83YKCu6— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) January 9, 2019

December 23rd, 2019

FDA Defers Approval of First Long-Acting HIV Therapy, Surprising Everyone

We HIV/ID specialists are lucky. For over two decades, steady progress in HIV treatment brings regular excitement to our field.

We HIV/ID specialists are lucky. For over two decades, steady progress in HIV treatment brings regular excitement to our field.

Some of these advances are incremental, but others represent major leaps forward. One such example of the latter is long-acting injectable therapy with cabotegravir (CAB) and rilpivirine (RPV) for maintaining viral suppression. This strategy — two injections every 4 or 8 weeks — obviates the need to take antiretroviral therapy daily.

Based on the results of the phase 3 efficacy studies called ATLAS and FLAIR, we know that injectable CAB/RPV is safe, well-tolerated, and (among those who chose to participate in the studies), highly popular. Patient-reported outcomes in study participants consistently showed they vastly preferred the long-acting therapy to the pill or pills they took previously.

It has been widely known for several months that FDA review of this injectable cabotegravir/rilpivirine strategy would take place before the end of this year. Most people (including me) expected FDA approval.

(Jeepers, the treatment even already has a brand name — Cabenuva, which sounds like a beach resort town in Mexico.)

However, recently we learned that the FDA sent a “complete response letter” (CRL) back to the filing company ViiV without approval. The reason?

The reasons given in the CRL relate to Chemistry Manufacturing and Controls (CMC). There have been no reported safety issues related to CMC and there is no change to the safety profile of the products used in clinical trials to date.

With the caveat that we don’t have the actual copy of this “CRL” (what strange code language in this announcement), it’s reassuring that no additional concerns have come up in this review regarding safety.

What’s tricky is the “CMC” part. I confess that aside from understanding what the individual words chemistry, manufacturing, and controls each mean in plain English, I didn’t fully grasp what CMC means when specifically applied to drug approvals.

Fortunately, my local Boston ID colleague (and our former ID fellow!) Dr. Katy Stephenson does:

CMC means chemistry, manufacturing and controls. It’s the regulatory section where you describe how the drug substance and drug product is made and tested for quality control. For example, when a drug is licensed and released with an expiration date, where does that date come from? It comes from product testing by the company and that data is submitted in the “CMC” portion of the FDA application. It even includes info on the packaging.

One can envision how this aspect of quality control could pose challenges for this treatment strategy. Storage, distribution, and packaging of cabotegravir and rilpivirine will be completely different from other antiretrovirals.

Meanwhile, HIV clinicians and our patients will need to wait a bit longer for approval of this regimen. Until we hear more details, we won’t know how long. But the data from clinical trials are solid enough that approval should be forthcoming eventually.

Which will then lead several fascinating questions, and (silver lining) we now have a bit more time to think about them:

- What proportion of those who are suppressed on simple therapy (one or two pills a day) will want to make the switch?

- The clinical trials only included people with no treatment failure or resistance — will we expand the treatment beyond this group?

- What will it cost?

- Will it require prior approval? If so, how will we make the case to the payers for a person who is doing well, which will by definition be essentially all the eligible patients?

- How will we “operationalize” it in the clinic? (Just writing “operationalize” gives me, a college English major, substantial pain — but it hurts a little less when I put it in quotes.)

- What pharmacies will dispense it?

- Will it be placed on hospital formularies? (Thinking probably not.)

- Is the oral lead-in necessary?

- What will we do about people who miss doses, or are lost to follow-up?

In other words, when — not if — CAB/RPV gets approved, this will be quite a bit different from any HIV treatment we’ve had before, with all sorts of questions and challenges.

Meanwhile, for those of you clinicians working the holidays, here’s what it’s like for us ID doctors:

Infectious disease docs taking patient history like #stewardmeme pic.twitter.com/cWxh9TPdWH

— Adi (@IDdocAdi) December 21, 2019