An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

December 15th, 2019

Should Oseltamivir Become an Over-the-Counter Drug?

News broke last week that oseltamivir — most commonly known by its clever (expired) brand name, Tamiflu — may be heading to pharmacies soon as an over-the-counter (OTC) drug, available without a prescription.

After hearing this, I immediately thought of several reasons both supporting and opposing this change — an ideal question for a poll!

Oseltamivir (brand name Tamiflu) may soon become an over-the-counter medication, available without a prescription. How do you vote, #IDTwitter and other clinicians, and why?

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) December 14, 2019

Clearly, way more ID-oriented clinicians support the status quo, with oseltamivir remaining available by prescription only. This 70%/30% split shows they feel even more strongly about it than the Brits did in their opposition to Jeremy Corbin.

(Too soon? Sorry.)

But even more fascinating than the poll results were the comments after the poll, many of them thoughtful and backed by clinical and scientific data. These were evident on both sides of the question.

I’ll summarize some of the more interesting opinions below. First, the NAY votes:

- Does the drug even work? A longstanding controversy, linked to concerns that the initial publications included only favorable data. Many cite various Cochrane Reviews (there have been several) as a reason to consider oseltamivir only modestly effective at best. Symptom improvement of only 1 day, or even less than that? Big deal, take some analgesics, curl up in bed, and wait it out.

- Most people have little idea what influenza actually is, using the term “flu” for all kinds of symptoms. “Stomach flu”, for example, is a commonly used lay term. Clearly

oseltamivir would do nothing for this illness.

oseltamivir would do nothing for this illness. - “Flu-like symptoms” are a common harbinger for several severe infections, and people who start themselves on oseltamivir will delay seeking attention for these conditions that need alternative treatments. Some of these might be respiratory infections such as pneumonia; others are systemic infections that cause fevers and chills first (such as pyelonephritis, streptococcal skin infections, and endocarditis).

- Some will jump the gun and think they need to start oseltamivir at the first sniffle, when all they have is a cold. Distinguishing influenza from other respiratory viral illnesses can be challenging — and the common cold (mostly from the zillions of rhinoviruses out there) is way more common (naturally) than influenza, especially when it isn’t flu season.

- Not only that — if people take it for a common cold or a “stomach flu”, they’ll be both wasting their money and risking side effects for no benefit. We don’t know what OTC oseltamivir will cost, but suspect it won’t be cheap — and this is an out-of-pocket cost, no insurance, with costs passed on to the patient. And no drug is 100% safe. Systematic reviews cite nausea and vomiting as the most common side effects of oseltamivir, but headache and psychiatric symptoms also may occur.

- Increasing access to oseltamivir will breed influenza resistance to it. A huge worry, one that we see globally already with ready access to antibacterial drugs. Do we want to risk this with oseltamivir and influenza? Of course not.

- We have enough trouble getting people to take their flu shot — now it will be even harder since they can get ready access to flu treatment. It’s like statin drugs and an unhealthy diet, right? License to ignore good medical advice.

Now, the YAY votes:

- Oseltamivir works best if started soon after the onset of flu symptoms — hence improving access to the drug is critical. Clearly sooner is better — the package insert says it should be started within 48 hours after symptoms start; studies show the greatest benefits if started in the first 6-12 hours. And who can reach their provider that quickly? What if it’s a weekend? What if your provider doesn’t believe it works? (See above.)

- Just the fact that there’s a controversy about whether it works shows it must work better than existing OTC “cough and cold” drugs, which are widely used. Can’t argue with that, as most of the colorful pills, liquids, and lozenges in that aisle are useless.

- The most rigorous and comprehensive overviews of the oseltamivir studies demonstrate conclusively the benefits of treatment. The key strength of this widely cited Lancet paper is that it used individual patient level data from the trials, which are much more reliable than aggregate study results. Those at high risk for influenza complications appear to benefit the most, reducing the need for antibiotics or hospitalization. (Addendum: And now I can link this recently published trial as additional evidence!)

- If people can get the drug easily at a pharmacy, it will limit the time they spend in doctors’ offices or hospital emergency rooms, reducing the risk they’ll spread flu to vulnerable other people. The elderly, the immunocompromised, those with multiple comorbid medical conditions (especially cardiac and pulmonary), pregnant women — they frequently visit health care settings, and the last thing they need is to spend time in waiting rooms with someone who has active influenza. Many hospitals (ours included) advise people to stay home if they have flu symptoms (unless of course they also have shortness of breath, difficulty staying hydrated, or other worrisome issues). “Sharing Isn’t Always Caring” say the signs in our hospital — clever.

- Making it over-the-counter doesn’t mean it needs to be in the aisle with the cough and cold “remedies” — a pharmacist could release it based on a symptom questionnaire or other screening tool. New Zealand and Japan have taken this approach — the drug is “behind the counter”, so not literally OTC — and this strategy apparently limits inappropriate use.

- There is no evidence that use of oseltamivir in people without influenza selects for influenza resistance. Indeed, without influenza being actually the diagnosis, the drug may not be doing any good — but it’s not leading to resistance. And in the countries that have it without prescription already, resistance to oseltamivir has not (yet) led to more local resistance.

- Influenza resistance to antivirals is unpredictable (to say the least), and not necessarily triggered by overuse. Take a look at this slide set reviewing the issue! Quoting Dr. Marc Lipsitch (who shared the slides): “The usual paradigm of use driving resistance doesn’t appear to hold.”

So where do I stand on the issue?

Gosh, this one is complicated.

While all the YAY and NAY votes make sense, for their own reasons, ultimately I thought about what I currently do in clinical practice.

When a patient calls me during flu season saying that they have fevers, chills, muscle aches, dry cough, and a runny nose, and that this illness “hit them like a truck” — I call in a prescription for oseltamivir rather than ask them to come in for an exam, blood tests, or a flu swab.

Why put them through this punishing trip to the hospital? Why expose other patients and health care providers?

Sure, it could be something else. And sure, it’s important to screen for other symptoms, and to tell them to come in if they’re not improving.

But the call to me seems like an unnecessary barrier; a good pharmacist can conduct the appropriate symptom screen and save people the hassle of reaching their providers by phone. They wouldn’t recommend osteltamivir for symptoms of “stomach flu”, or for a runny nose only, would they?

So bring on behind the counter oseltamivir, available without a prescription! Under the guidance of a wise pharmacist!

And remember — Tamiflu was selected as the one of the greatest expired (it’s now generic) antimicrobial brand names ever by Dr. Raphy Landovitz in this important podcast.

So go ahead, listen again to the whole thing.

And now that you’ve read this far, how would you vote?

Thanks to those who offered the numerous thoughtful responses and insights offered in the original poll. Let’s see what this one shows.

December 8th, 2019

A Midyear Letter to First-year ID Fellows — With Sympathy, Gratitude, and Hope!

Dear First-Year ID Fellows:

Right around now, some of you might be feeling a bit prickly. The workday is long, the supply of daylight dwindles daily, and the cold winds blow in from the north. While friends outside of medicine gear up for holiday time off, your plans might include some hospital coverage. Some of you have already worked Thanksgiving Day (and we thank you for that).

This testy feeling is totally understandable and appropriate — we definitely get it. Doing ID consults on hospitalized patients is hard — doing them during the first year of ID fellowship particularly so. For the record, let’s explore the reasons:

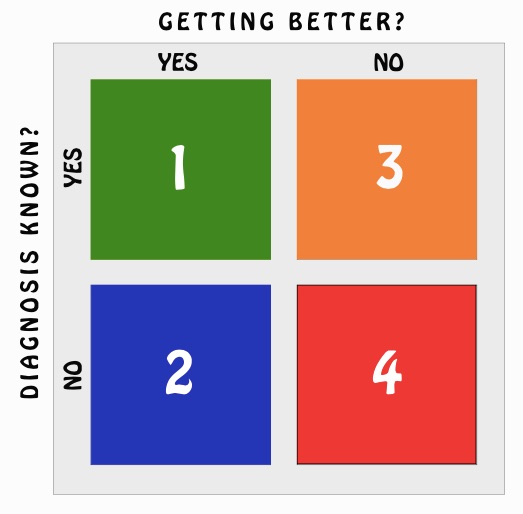

- Nobody gets ID consults on straightforward cases. I’ve said it many times, but it bears repeating — if the diagnosis is clear, the treatment going fine, and the patient improving, they won’t call you. Remember the Four States of Clinical Medicine? If not, here’s a reminder:

Maybe someone set up a clinical obstacle course just for ID, because all your consults come from Boxes 2, 3, or (shudder) 4 — actually, most from Box 4. Our job: move the patient back to Box 1 (best) — or at least Box 2 (second best) or Box 3 (third). Not always easy.

Maybe someone set up a clinical obstacle course just for ID, because all your consults come from Boxes 2, 3, or (shudder) 4 — actually, most from Box 4. Our job: move the patient back to Box 1 (best) — or at least Box 2 (second best) or Box 3 (third). Not always easy. - Certain ID consults challenge our emotions as well as our intellect. The previously healthy young person with a poor-prognosis hematologic malignancy and fevers despite broad antibiotic and antifungal coverage. The elder matriarch or patriarch of the family with a devastating stroke and recurrent aspiration, large family huddled in the room. The young man (it’s usually a man) with a spinal cord injury from a gunshot wound and severely infected pressure ulcers. The too-late HIV diagnosis with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) unresponsive to antiretroviral therapy. The person with diabetes who continues to lose their battle with vascular disease, requiring multiple amputations. Substance use disorder and all its various infectious complications. Wow, ID consults can induce sadness.

- Most surgery goes well — but when it doesn’t, the ID part is particularly painful. I have enormous respect for my surgical colleagues, who do things for patients I could never do in a million years. But when surgery goes wrong, and there are infectious complications, can anyone find a tougher role for the ID consultant than this? Since we’re on the floors more than the surgeons, sometimes it feels like we bear the brunt of the patient’s and their family’s disappointment and anger as much as — if not more than — the surgeons themselves. I doubt that’s true, but it can feel that way. Ouch. Particularly Ouch! when you’re a first-year ID fellow.

- There’s a ton we don’t know — and not knowing what we don’t know is part of being a first-year fellow. Back when I was a clinical fellow, I rounded repeatedly on a sick patient in the ICU who had fevers every single day. He had been admitted around the time of the signing of the Magna Carta, so it had been a lengthy hospital stay, to say the least. Despite our meticulous care and trying every antibiotic strategy known to humankind, every day — another fever. You know the case — a Fever of Too Many Origins. Frustrated, I repeatedly turned to my attending for help. Surely this esteemed ID faculty member with years of experience will solve the endless fevers problem. His response? “Sometimes we don’t know what’s going on, but we have to keep on trying anyway.” Not particularly articulate, but … Yep.

- Different supervising faculty have different expectations. Just when you’re getting comfortable with Dr. Attending #1, who wants short notes, targeted histories, just the antibiotics, only the WBC and creatinine, and then your bottom line impression and plan, along comes Dr. Attending #2, who wants every detail of the history, including every infinitesimally small data point — all the medications (with doses), all the labs (including the calcium and troponin), all the micro, and all the imaging, culminating in a note with the length of Mandell, Volume 1. (That’s 1919 pages, in case you’re wondering.) What’s the right approach? That’s the problem — there is no right approach for everyone. Just different clinical styles — but you, First-Year Fellows, are the ones who have to adapt.

Despite the above challenges, I hereby boldly proclaim that there is reason for optimism and genuine hope.

Reason #1: You are nearly half-way done. The end of this month is not just holiday season; it’s also the 50% mark on your first year. (I did the math.)

Reason #2: Your replacements are on the way. Match Day was last week. New fellows are really coming, and coming soon!

Reason #3: The hospital is quiet during holiday season. Yes, superstitious clinicians never make such optimistic predictions — but aren’t we people of science? Speaking as someone who has worked Christmas nearly every year since the start of the Clinton presidency, I can assure you that the hospital census goes way down in late December.

Reason #4: Free cookies, cakes, candies, and other snacks. These will start magically appearing on the hospital floors any day now, culminating in a peak supply on December 25.

Reason #5: The days will soon start getting longer. Sometime right after December 21, 2019, the Earth’s axis will gradually start tipping a bit more toward the sun each day. Promise!

Reason #6: You have already learned a tremendous amount of clinical ID! It is remarkable how steep the learning curve is for you ID fellows. Only around 6 months into your training, you frequently arrive at diagnoses and recommendations for consults that require little, if any, modification from us attendings. Your histories draw information from the patients, the families, and the outside hospitals; you relay our thoughts accurately and concisely to the referring teams. Cases that previously would have been overwhelming you now handle with aplomb. Keep up the good work, we appreciate it!

Reason #7: A man can play “All Star” on melons. If that’s not reason for optimism, what is?

(Start at 1’40” if you’re having a busy consult day.)

(Four States of Clinical Medicine graphic by Anne Sax.)

December 1st, 2019

On World AIDS Day 2019 — Wouldn’t It Be Nice…?

With apologies to a 1960s band with a flair for complex harmonies and evoking warm ocean breezes (as the first winter storm barrels in), here’s a miscellaneous list of wishes for World AIDS Day.

Wouldn’t It Be Nice …

- If everyone with HIV could be on suppressive antiretroviral therapy? Here are the latest estimates, showing we’re only a bit more than halfway there:

https://twitter.com/WHO/status/1200920676275765249?s=20

- If antiretroviral therapy had no side effects? Our treatments are so much safer and better tolerated than they were — hooray! — but they’re not perfect. Weight gain is the latest adverse effect of greatest concern; Dr. Andrew Hill presented a superb summary on the topic at the recent European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) meeting.

- If all those at high risk for acquiring HIV could receive PrEP? Here in the United States, the high price of PrEP draws the most attention as a barrier. However, the issue is far more complicated than just price (though that doesn’t help) — it starts with the fact that those at greatest risk of acquiring HIV here (young MSM of color, especially in the Southeast) are the least likely to be engaged in any longitudinal healthcare. And many countries don’t cover PrEP at all.

If HIV stigma disappeared? All of us follow patients who have so internalized the societal stigma of having HIV that they can’t bear to tell anyone about their diagnosis — not even close family members or friends. Some have lived with this pain for decades. Boy, HIV really needs a stigma-ectomy.

If HIV stigma disappeared? All of us follow patients who have so internalized the societal stigma of having HIV that they can’t bear to tell anyone about their diagnosis — not even close family members or friends. Some have lived with this pain for decades. Boy, HIV really needs a stigma-ectomy.- If the pricing of HIV medications in this country actually made sense? Imagine a world where setting the price of HIV drugs were a transparent process based on actual value, and didn’t involve convoluted, secret negotiations between payers, manufacturers, and pharmacy benefit managers? What a wonderful world that would be! (That’s a different song.)

- If the confirmatory test after a reactive HIV screen were an HIV RNA (viral load) rather than a HIV-1/2 antibody differentiation assay? As I’ve written before, this would greatly speed getting people an accurate diagnosis, and furthermore dramatically reduce the “worry days” with a false-positive screen.

- If every HIV resistance test a patient ever had were kept on a secure but easy-to-navigate site? HIV resistance testing entered clinical care in the late 1990s. It has been provided through multiple different labs with a dizzying array of reporting formats and interpretations. Poorly suited to display on electronic medical records, these reports are best seen in their original format. Perhaps a Dropbox-like repository, with a folder for each patient containing the reports? You’re welcome.

- If there were an effective HIV vaccine? As two major clinical trials proceed — HVTN 702 and 706 — we eagerly await results!

- If HIV could be cured? Last, but not least. We learned of our second case of likely HIV cure early this year at CROI, and a third is out there too. All three, however, required a stem cell transplant. While hardly a scalable approach, these cases prove that prolonged, drug-free remissions are achievable.

Surf’s up!

November 25th, 2019

Vaccine Defenders, U=U Holds Up, Zika Is Gone, and Other ID Things to Be Grateful For, 2019 Edition

An excellent episode of the Freakonomics podcast introduced me to the headwinds vs tailwinds asymmetry, and how we humans perceive life.

It goes like this: We go for a walk, a run, or a bike ride, and the wind faces us dead-on, making the exercise a struggle.

(In windy Boston, the wind is always in my face. Always always always.)

When the route changes, there’s a brief moment of relief, but it’s short-lived. What we remember about the experience is the headwind, certainly not the boost the tailwind might have given us on the way home.

The researchers on that podcast argue that this same blindness to various good things, privileges, and benefits is how we perceive all of our life. We’re intrinsically wired to complain about the barriers and struggles.

In short:

Barriers and hindrances command attention because they have to be overcome; benefits and resources can often be simply enjoyed and largely ignored.

While evolution might have hard-wired this attitude in us for survival purposes, it can also make us into a bunch of unappreciative whiners.

Which is why the flip-side — expressing gratitude — is so important. Research consistently shows it makes us happier. And it definitely makes us better company, an important consideration as we approach the holiday season.

In that spirit, in what’s become a Thanksgiving Holiday tradition, I list below a series of ID/HIV things to be grateful for in late 2019. And hey, there’s so much to be grateful for!

- Brave, authoritative, and respected voices continue to speak out against the anti-vaccine movement. There are many such voices out there, and IDSA has done a terrific job as an organization, but I want to highlight especially Dr. Peter Hotez. He appears regularly in public and in print to defend vaccines, risking his own safety; he has also written a moving and personal book entitled Vaccines Did Not Cause Rachel’s Autism: My Journey as a Vaccine Scientist, Pediatrician, and Autism Dad. Check out the ratings for this book on Amazon, and you’ll find a painful dichotomy — either 5 stars or 1 star — with the negative comments demonstrating how vicious the anti-vaccine movement can be.

Ugh, stalked today/tonight at a NY peds infect dis conference by a couple saying they represent Children's Health Defense, filming me, asking provocative questions. I never know how to best handle it other than to try answering their questions and be respectful? No win situation pic.twitter.com/g7KiiSkqye

— Prof Peter Hotez MD PhD (@PeterHotez) November 24, 2019

- An Ebola vaccine works! In perhaps no other disease will a vaccine play such a critical role in getting control of an outbreak. This is wonderful, very welcome progress!

- U = U (undetectable equals untransmittable) continues to hold up. Perhaps the most transformative finding in the history of HIV medicine — that people on successful HIV treatment don’t pass the virus on to others sexually — remains a rock-solid fact. I’ve included U = U here before several times, but why not continue to celebrate it?

- HIV incidence in many urban regions in the USA drops. In New York City, for example, 1,917 people were diagnosed in 2018, a 67 percent decline from 2001. Treatment as prevention and PrEP are yielding these impressive results.

- Zika is all but gone. Remember how crazy things were in 2016? Especially for couples who wanted to have children? And for us ID doctors (and primary care and OBs) trying to advise them? Yes, Zika could come back (and likely one day will), but let’s be grateful for our current situation compared to that insane period.

- New antibiotics, some with new mechanisms of action, expand our treatment options. No, they’re not perfect, and some are only incremental advances, or targeted at rare clinical situations — but great anyway to have lefamulin, pretomanid, omadacycline, eravacycline, meropenem-vaborbactam, imipenem-relebactam, cefiderocol (with some confusing data on this last one, still to be sorted out). Now let’s try to fix the economics of antibiotic drug development!

- Additional studies continue to demonstrate the clinical benefit of ID consultation on outcomes. Just a few recent examples — candidemia, sepsis, and long-term outcomes in Staph aureus bacteremia. The parade goes on and on!

- A “Shorter is Better” philosophy about duration of antibiotic therapy moves into clinical practice. And with this updated super list from Dr. Shorter-is-Better himself, Brad Spellberg, why not?

@aurdinh Okay, Aurelien, 7th pyelo study added to table and to website. Thanks for bringing your study to my attention. Latest version of Table (updated 11/14/19) below. pic.twitter.com/Q5Rmub2HRP

— Brad Spellberg (@BradSpellberg) November 14, 2019

- Pragmatic clinical trials in ID give us important new strategies for therapy. The most notable examples in the past year are the POET and OVIVA trials, demonstrating the noninferiority of oral to IV therapy for endocarditis and osteomyelitis. More of these, please!

- The “Ask the Experts” section on the Immunization Action Coalition remains a gold mine of useful information. I’ve mentioned it before, but that doesn’t mean I can’t still be grateful! Barely a week goes by without my consulting this site.

- Shorter treatment courses for latent TB gain traction. Drug interactions aside, who doesn’t prefer 4 months of rifampin to 9 months of INH? Can 1 month of isoniazid/rifapentine be far behind?

- New guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of Lyme Disease are imminent. The draft guidelines have already been released — final version expected soon.

- Dolutegravir-based regimens are increasingly available globally. In many settings that previously had only efavirenz (first-line) and lopinavir/ritonavir (second line), dolutegravir represents major progress — for both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients. It will be important to see how this big change in strategy works out, which is the primary goal of this observational study.

- ID fellows continue to amaze us. Smart, mission-driven, and hard working, they take on the most complicated cases in the hospital with aplomb. As my down-the-hall neighbor Dr. Sigal Yawetz says:

And most notably the amazing bright ID fellows we interview and recruit each year. And the work done by former trainees. Our field continues to attract bright minds and that's most exciting, looking towards the future.

— Sigal Yawetz MD (@sigal_md) November 17, 2019

Happy Thanksgiving! What are you grateful for this year?

November 18th, 2019

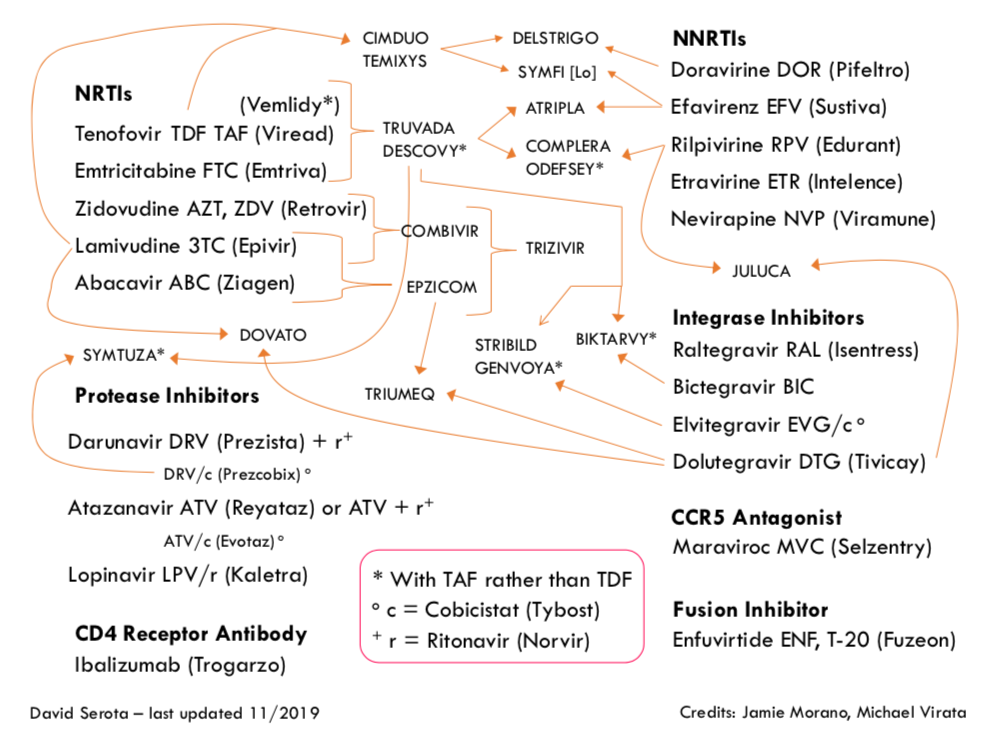

The Best Guide to HIV Drug Names — Yours for Free!

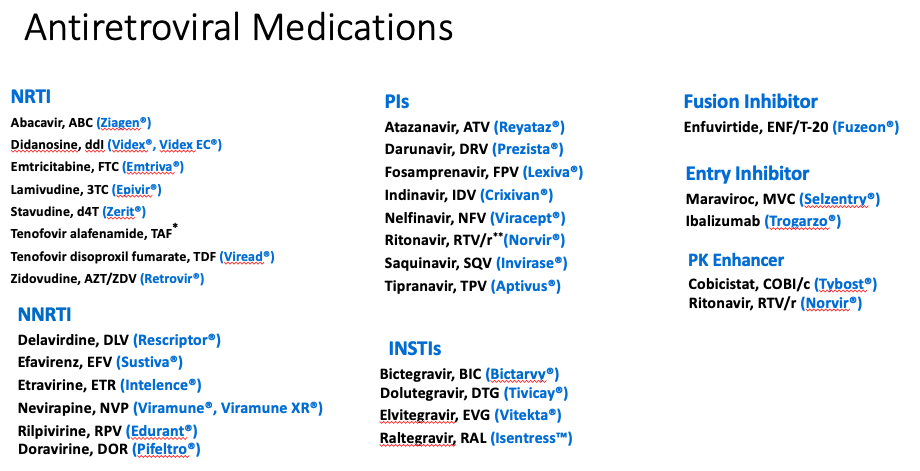

Earlier this month, I noted something that all of us ID/HIV specialists should readily concede — namely, that learning the names of the HIV drugs is fiendishly difficult.

Afterwards, I heard from a few old-timers (that is, people like me). They acknowledged that we were lucky to experience the roll-out of these medications (and their convoluted names) in real time, which made learning them easier.

And some people currently struggling with the names wished for a logical code to the nomenclature, analogous to the HCV drugs. The HCV protease inhibitors, for example, all wrap up with -previr, e.g., telaprevir (may it R.I.P.) up to glecaprevir. And the NS5A inhibitors end with -asvir, e.g., velpatasvir and pibrentasvir.

By contrast, what do we get with HIV drugs? While all of the integrase inhibitors have -tegravir in their names — hooray! — the NRTIs, NNRTIs, and PIs are a mess.

Specifically — why do all the NNRTIs end with -ine (nevirapine, rilpivirine, doravirine) except efavirenz?

(Brief aside — efavirenz. What a bizarre word. No wonder it causes CNS toxicity.)

Plus, don’t many of the NRTIs end with -ine as well?

Of course they do (zidovudine through emtricitabine) — that is, until they don’t (abacavir). And this NRTI just happens to end with -avir, which is how all the HIV protease inhibitors end.

Bedlam!

To help the confused masses, some of you kindly sent along your “cheat sheets,” many of which were better than the one I posted. All of them shared the strategy of excluding drugs we no longer use, which simplifies things a lot.

This one, from Dr. Kristen Brown, was excellent — it even includes a few resistance pearls — useful! However, due to the complexity of resistance, this will need eternal tweaking (even this one), so Kristen says she might retire that section.

But, as she noted, there was another choice pick — and that was from Dr. David Serota (a.k.a. @serotavirus).

After I reached out to him, he not only shared it in PDF and PowerPoint format, he allowed some niggling input from me (mostly for consistency), and said it was fine to post here. Furthermore, for a small fee, he’s offering signed, laminated copies, suitable for framing.

So without further ado, I bring you the very best HIV medication cheat sheet available as of November 2019:

So, here are a few things that make this so great:

So, here are a few things that make this so great:

- It excludes the old drugs we never use anymore — except for Trizivir, which he kept because he just likes that name.

- Generic names are first, followed by their three-letter abbreviations, then their brand names — the right order.

- Brackets and arrows create the branded coformulations.

- Boosters (ritonavir and cobicistat) are a single small letter (DRV + r), and their single-pill coformulations are separated by a slash (DRV/c).

- The legends box clearly explains the confusing world of TAF vs. TDF and the two boosters.

Critics might say this is still too complicated.

Yes, it’s still complicated — but why do you think they pay us the big bucks?

November 11th, 2019

When TV Gets ID Wrong — Or At Least Not Quite Right

A busy week for Infectious Diseases on television!

First, Dr. Aditya Shah, an ID doctor at Mayo Clinic, treated us to several snippets of truly idiotic ID-related drama in a network television show.

After seeing them, I commented:

Hey, my services to this show to help you talk about infectious diseases without sounding dumb are available at a very reasonable price.

My offer stands! For this show! And all of television! If you never want to sound stupid about Infectious Diseases again, call me!

For those of you who wandered over here to an ID blog without much ID background, here’s why the linked very tense hallway exchange sounds (and looks) particularly moronic:

- “Howard has a superbug.” Doctors hardly ever use this term. Yes, it’s commonly used in the popular press to describe a drug-resistant infection — but think of it like “germ”, another word you rarely (if ever) hear doctors say when talking to other doctors.

- “A C. diff infection?” He looks genuinely surprised, although C. diff is one of the most common infections in hospitals today. Plus, has there ever been a single clinician in the world who uses the term, “a C. diff infection”? Nah. Just C. diff.

- “It’s resistant to all medication.” The clincher! Because even though C. diff can be difficult to treat, this is due to alteration in the normal microbiome, not antibiotic resistance. We don’t even do susceptibility testing — which makes one wonder what could possibly be written on that piece of paper they are reading.

Second, the press picked up — in a big way — a paper that reported the discovery of a “new HIV strain.”

Second, the press picked up — in a big way — a paper that reported the discovery of a “new HIV strain.”

To clarify, it’s a new subtype, called “subtype L”, and it was identified by scientists at Abbott Laboratories using new techniques on stored blood specimens.

We have no reason to doubt their findings, which seem sound enough, and it’s a plus that our major diagnostic labs keep track of HIV genetic diversity.

But it’s hard to come up with other HIV research where the amount of news coverage (huge) was so disproportionate to the clinical impact of the finding (zero).

As my virologist colleague Dr. Jon Li says, “Media reports play on our fascination and fear of mutating viruses.” Perfectly stated! But to get back to the non-existent clinical implications, this “new” subtype L would:

- be picked up by standard HIV diagnostic tests,

- respond to antiretroviral therapy,

- probably never be encountered anyway, since only three examples have been found, most recently nearly 20 years ago.

One of our local news stations chatted with me about it here — I think they did a good job reframing the “story” to be about more important issues in HIV today.

Next time they may want to speak to my mother, who commented:

Interesting news story in that it’s all negatives.

Not a new strain.

No change in diagnosis.

No change in treatment.

Not something to be worried about.

Finally, we have another “brink of HIV cure” report, as a biotech company called American Gene Technologies (AGT) “submitted a nearly 1,000-page document to FDA.”

And within its pages just may lie the cure for HIV/AIDS.

It’s hard to comment whether this company’s immune-based approach to HIV cure will ultimately be a promising strategy — it’s in the very early stages of development, with Phase 1 studies tentatively starting soon.

But watch the accompanying video — which statements make you roll your eyes the most?

- “Since the late 1980s, a few antiretroviral drugs …” Look at this list! The word “few” means “a small number of” — there are way more than a few.

- “No treatment actually cures HIV — that’s until now …” Hey, we all hope for the best with this novel approach, but no one has been cured with it yet.

- “[Taking HIV drugs] is a life sentence of taking that toxic chemotherapy …” Yikes, this is overly harsh. Most people with HIV have few side effects from treatment, many have none. Plus, is the analogy of taking medication every day to imprisonment appropriate? Do we say people with high blood pressure have a “life sentence” of taking anti-hypertensive medications?

- “The single-dose drug has a simple purpose — to eradicate HIV once and for all so that people can live.” Aren’t people with HIV living now? Isn’t survival for people on treatment comparable to those without HIV?

- “We wanted to get these people out of jail and back to a normal life.” Good grief, he’s back to that prison metaphor again.

Before anyone accuses me of being overly skeptical about AGT’s approach, I am thrilled that scientists both in academia and industry are working on an HIV cure. And I’m hopeful a cure will one day be a reality for my patients and the millions of others with HIV — whether it’s AGT’s strategy or the work of other investigators.

But we definitely need cautious, scientific reporting — and way less hype.

Meanwhile, that Dr. Shah sure is funny.

Me, when the team wants to use unneeded meropenem #stewardmeme pic.twitter.com/rcoDaw7b07

— Adi (@IDdocAdi) November 9, 2019

November 3rd, 2019

Learning the Names of HIV Drugs Is Horribly Difficult — Here’s Why

Happens every time. We start teaching about HIV, and at first, everything is going great.

Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, clinical presentation. The students are right there with us.

However, then we start covering treatment — and things immediately get tricky.

Because no matter how engaged and brilliant they are, and no matter how scintillating we are, when the long list of antiretroviral agents appears, their eyes glaze over with fatigue.

Instant somnolence. Like someone turned up the temperature in the room, dimmed the lights, and passed out soft blankets and pillows.

And it’s no wonder! There are lots of drugs, with a dizzying array of names, abbreviations, combination tablets, and mechanisms of action.

We haven’t helped matters by following these RULES OF HIV MEDICINE, all of which were designed by evil creatures (with advanced degrees in medicinal chemistry and marketing) to make learning HIV medications terrifying. Here are these baleful rules:

- All drugs must have at least three names. Generic, brand, and 3-character abbreviation. To make matters worse, some have more than three names, starting with the very first drug way back in 1987, zidovudine. It was also called AZT (that’s what most people called it), ZDV, and Retrovir (that’s 4, including zidovudine). It also showed up in Combivir and Trizivir, for good measure. Now that’s just mean.

- HIV specialists must refer to them by different names at different times, for no apparent reason. Do we do this to maintain our special status? To be whimsical? To deliberately confuse others, just for sport? Whatever the motivation, it’s working wonderfully to keep this knowledge the very definition of arcane.

- Names of combination tablets should have nothing in common with their parent drugs. Some recent examples: Combine Tivicay and Epzicom — what do you get? Triumeq, of course. Descovy plus Edurant? Odefsey! See, isn’t this fun?

- Some of the abbreviations must bear no resemblance to either the generic or the brand name. Example — what does “3TC” have to do with the word “lamivudine,” for which it is the widely accepted abbreviation? Hint: nothing. Unless you check its chemical structure. And who, we might ask, will be doing that? And since emtricitabine is very similar to lamivudine (you knew that, right?), emtricitabine is abbreviated “FTC,” which makes all kinds of sense since emtricitabine starts with an “F.” (Oh wait. No it doesn’t.) The first time this disconnect between the true and abbreviated name came up was with the abbreviation for the drug zalcitabine, which was abbreviated “ddC”, for a chemical name that no one used. That’s right, two small “d”s followed by a capital “C.” Careful readers will note that zalcitabine has neither a single “d” nor a capital “C.” Fortunately, few prescribed this lousy drug anyway, which made its suitably horrific brand name (“Hivid”) just a faint stain on the history of HIV drug development.

- Names of different drugs might sound alike, but will have nothing whatsoever to do with each other. Nelfinavir (Viracept) and nevirapine (Viramune) give us an example where both the generic and the brand names sound kind of similar. But they are completely different drugs — different dose, mechanisms of action, side effects. About the only thing they have in common was that they are both HIV treatments. You think people have confused them? You bet.

- Drugs should change their names when they come out in different formulations. Take a look at the various name changes when tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) spawned tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) — this generated a whole new crop of confusing drug names, as both are extensively coformulated. But the trickiest (and saddest) story is saquinavir, the very first protease inhibitor. First it was Invirase, taken as three 200 mg capsules three times a day. Due to poor bioavailability, Invirase was later changed to the humongous soft-gel capsules called Fortovase, taken as six capsules three times a day. (Yes, that was the dose — it was practically a patient’s whole diet.) Then, with the realization that humans could not subsist on a drug that was six large capsules three times a day, saquinavir went back to being Invirase, but now had a new size (500 mg), and was taken as two tablets twice daily with ritonavir twice daily. Got that? Of course not.

- The order in which drugs are listed in combination pills will be different in different sources. After years of litereally everyone writing TDF/FTC as the abbreviation for the pill that contains tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and emtricitabine (FTC), along comes the first PrEP study, which reversed them. Not only that, they used a dash rather than a slash — “FTC-TDF.” Because why? And with three- and four-drug combinations, which drugs goes first? What’s the order? Alphabetical? By mechanism? Your guess is as good as mine.

- If people are getting used to the three-letter abbreviations, go ahead and abbreviate the drugs in combination tablets with one letter, not three. This is a relatively recent trend, but one that people eager to make HIV drugs harder to learn surely must support. Example: When darunavir is given with ritonavir, it’s often written “DRV/r.” Ritonavir is changed to a lower case “r” (and not abbreviated RTV) to denote that it is not being used as an antiviral, but as a pharmacokinetic booster. Makes sense, sort of, except that nobody shared the code. However, the slash implies that it’s a combination tablet, which it most certainly isn’t. When we write or say “DRV/c,” or Prezcobix, however, this is a combination tablet, with the “c” standing for “cobicistat.” So cobicistat is also abbreviated as one letter, unless you are fans of the cute-sounding “COBI,” which is four letters, and for the record is pronounced like the former Los Angeles basketball star and the famous Japanese beef, but definitely has nothing to do with either one of them. But why stop there and let darunavir have all the fun? Let’s move right on to “ECF-TAF,” which stands for elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine (FTC, remember?), and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF). Certainly it makes all kinds of sense to use single letters for three of the four drugs in this combination tablet, then three letters for one of them — following a dash. Right? I mean come on, it’s so obvious.

So what’s a poor clinician to do? Some great responses here, I especially liked this one:

I’ve had folks threaten to get an interpreter when we were discussing HIV meds in our hospital formulary meeting.

— Adam Lake MD (@ACLakeMD) November 3, 2019

My solution (ha) to this mess will come in Part 2 of this topic. In the meantime, I welcome your input about how we should go about teaching (or learning) this material.

And it’s obviously time to reprise this classic. Take it away, Trip!

October 27th, 2019

The Enduring Appeal of Live, Face-to-Face, Real-Time Continuing Medical Education

Around 15 years ago, after high-speed internet became a de facto part of work life and was rapidly becoming more widely available at home, I attended a meeting with other medical educators to decide what to do about our various post-graduate courses.

The wisdom in the room was that most continuing medical education (CME) would soon migrate online, replacing live courses.

It just made too much sense — CME could be done at home, or from the office, and would not require the cost or hassles of travel, parking, and hotels. Online CME would minimize time away from the office, and would also be more family-friendly.

The message I took away from this meeting about our beloved courses?

They were doomed.

My wife, a practicing primary care pediatrician, agreed — why would anyone travel to go to CME courses when they could get the same required credits in the comfort of their own homes? And she’s hardly ever wrong.

But this is one of those rare times where everyone got it wrong. Live CME courses never went away. In fact, in the annals of bad predictions, the anticipated demise of face-to-face CME is right up there with Decca records’ choosing not to sign a certain Liverpool-based rock band because “guitar groups are on their way out.”

Yes, there are plenty of online CME opportunities. But live CME remains extraordinarily popular — in a survey done of clinicians by a marketing company, 80 percent reported that live conferences were the CME activities they participated in most often. Live CME was also the format they preferred above all others.

I’m thinking about this today because tomorrow is the first day of our annual course, “Infectious Diseases in Primary Care”. Not only have we had steadily increasing attendance for years, we’ve also been able to add an additional optional symposium on HIV and viral hepatitis for the PCP. The attendance at our course is twice what it was 15 years ago.

And we’re hardly alone. (Though I like to think our trying to get our very best teachers cover the most important topics are at least possibly responsible.) Our hospitalists at the Brigham started a course a few years ago that has been staggeringly successful — so big it sells out every year. I hear from my colleagues at other academic medical centers that they also continue to have excellent demand.

So what gives? I can think of a few explanations.

- People concentrate better and retain more information when they’re away from the distractions of work and home life.

- People value networking with colleagues as much as the educational content.

- With a shift toward salaried positions and away from traditional fee-for-service, CME is built into the contract as a benefit; also, time away from the office is no longer a negative for personal revenues.

- Physician Assistants, Nurse Practitioners, PharmDs, and other non-physician health professionals increasingly want the same medical education, greatly increasing the pool of participants.

Any others? Whatever the reasons, it seems that live CME is here to stay, at least for now.

And for the record, I would have signed them.

October 21st, 2019

Amoxicillin for Chronic Low Back Pain? Are You Kidding Me? In Defense of a Controversial Clinical Trial

The BMJ just published a randomized trial comparing amoxicillin to placebo for people with chronic low back pain.

I kid you not.

The appearance of this trial elicited all kinds of snark from the medical community. Here, check this out, along with the responses:

Important RCT for anyone who’s been treating low back pain with <checks notes> amoxicillin https://t.co/RIxIVSr3kb

— David Juurlink (@DavidJuurlink) October 19, 2019

Dr. Juurlink, definite points for that <checks notes> stage direction! Love it.

But allow me to defend the people who did the study, and go even further — this is exactly the sort of practical, hypothesis-testing trial I wish we’d see more often.

Consider the problem — chronic low back pain. The bane of Western Civilization, it occurs in a quarter of the adult population. The misery from this condition results in millions of annual office visits a year, countless days out of work, and heavy economic losses.

Usually we don’t know the cause. And for severe sufferers, our medical treatments and surgeries offer inconsistent benefits.

Along comes the idea that a subset of back-pain patients — those with certain inflammatory changes on imaging, called “Modic” after the person who described them — might have a low-grade infection as the cause of this inflammation.

The theory is that a degenerating disc provides a suitable spot for this infection to settle, presumably after transient bacteremia. It would have to be a very indolent, slow-growing infection, as people with chronic low back pain don’t have fevers or other symptoms of acute infection, and also lack laboratory evidence of infection or inflammation.

Based on animal and human data, the leading candidate for this kind of infection is none other than our old friend Cutibacterium acnes, shown here again in a very good mood.

(Maybe it’s happy because, as I’ve written before, Cutibacterium acnes used to be Proprionobacterium acnes. The new name is a zillion times better, especially if it’s pronounced like a cute little puppy, and not like a paper cut, or like an old coot.)

We ID doctors are quite familiar with C. acnes as a relatively common cause of prosthetic joint infections, especially of the shoulder; dermatologists know it as one of the primary bacteria involved in <checks notes> acne.

C. acnes also sometimes pops up in blood cultures, usually as a contaminant — but maybe those aren’t contaminants after all!

(Cue dramatic music here.)

The idea that C. acnes could contribute to chronic low back pain has been supported by the occasional isolation of the organism during spine surgery, and animal models showing the bug could induce these Modic changes in rabbits. This information led to a controversial randomized clinical trial comparing amoxicillin-clavulanate to placebo in adults with chronic low back pain, showing significant improvement in the treatment arm.

A subsequent systematic review concluded:

… further work is needed to determine whether these organisms are a result of contamination or represent low grade infection of the spine which contributes to chronic low back pain.

All of which brings us back to the recent study, which enrolled 180 people with chronic low back pain and Modic changes (of two types) on imaging. They were randomized to receive oral treatment with either 750 mg amoxicillin or placebo three times daily for three months. The primary outcome was a validated disability score a year later. They set a difference of 4 points on the scale as being clinically meaningful.

The results showed that the amoxicillin group had significantly lower disability scores than the placebo group, but the difference did not meet the threshold for being clinically important (it was only 1.6 points). Plus, nearly twice as many in the amoxicillin arm experienced a drug-related adverse event.

I certainly agree with the authors’ conclusions that the “results do not support the use of antibiotic treatment for chronic low back pain”, especially if you consider the added potential problems of encouraging antibiotic resistance and alteration of the human microbiome.

But kudos to them for doing the research — even negative studies are important. It could have been an H. pylori and peptic ulcer disease, but was C. pneumoniae and CAD instead.

But just imagine if it worked!

October 14th, 2019

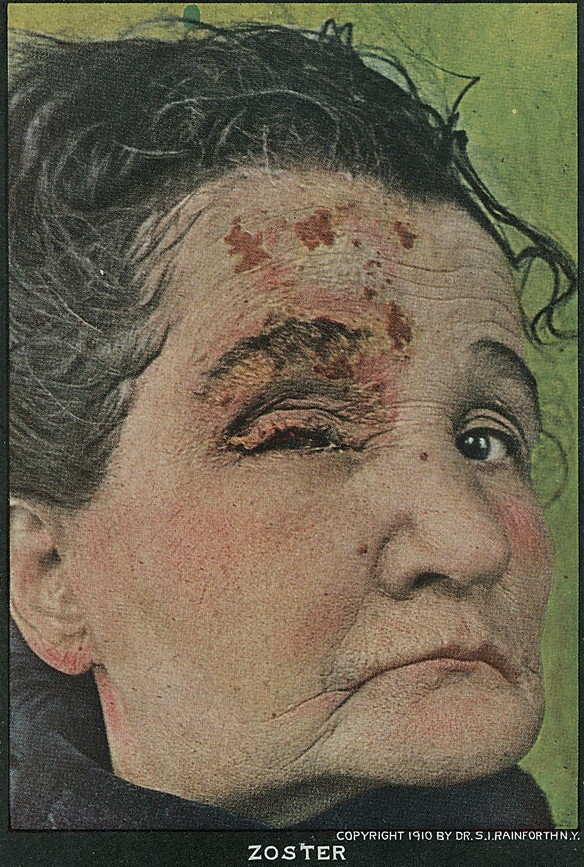

Common Questions About the Shingles Vaccine — Answered Here!

Here’s an interesting email from my friend and ID-colleague Dr. Carlos Del Rio (shared with his permission):

Went Tuesday to see my PCP for a routine visit and had my second dose of Shingrix that day. I had gotten my first dose about 3 months ago and had severe chills and even a fever of 38.5 after the first dose. With the second dose the response was not as severe but did have chills and rigors for about 18 hrs. Stupid of me, but the next day I went to get my labs checked, and everything was fine except my HS-CRP which was 14.72 (nl < 10 and in the past I had been < 1.0).

Anyway…..Shingrix is a good vaccine but it is a tough one to take and really gives you a nice TNF storm!

For the few of you out there in ID-World who don’t know him, you must understand it takes quite the force to slow down the high-energy machine that is Carlos. He is the very definition of indefatigable. So it’s not surprising he told me he went to work after both shots, rigors and all.

(Brief aside — congratulations, Carlos, on your well-deserved award!)

But Carlos’ post-shingles vaccine experience reminds me that we’re now two years into the recombinant zoster vaccine (RZV, Shingrix) era, and that immunization for this common adult infection — shingles, or zoster — has brought with it all sorts of new questions.

So here are a bunch of common ones we ID doctors field on a regular basis:

- Who should get it? The vaccine is recommended for essentially all immunocompetent people over 50. So if you were born anytime before October 1969, this means you. People conceived during the Woodstock music festival or right after the Miracle Mets won the World Series are off the hook, at least for a few months longer. Two shots, separated by 2-6 months.

- “Immunocompetent” adults — so nobody else? While immunosuppression is not a contraindication to the RZV, the data supporting its use in this population have not yet informed current guidelines. For now, it’s totally reasonable to offer RZV to people over 50 receiving low-dose immunosuppression, or to those with stable HIV on treatment, or to individuals who have had an autologous stem cell transplant. For higher degrees of immunosuppression, adopt an individualized approach — and remember that there is a theoretical concern that the adjuvant in the vaccine might stimulate organ rejection or a flare of an underlying autoimmune condition. We’ll see if this turns out to be a legitimate worry, so far it hasn’t.

- No upper age limit? Use your judgment — if it’s a healthy 88-year-old with few medical problems, go ahead and give it. The risk of shingles increases as we age, and such a person will likely live several more years and could benefit from the vaccine. However, if it’s someone with multiple serious comorbid medical problems, then skip it. And yes, there are side effects — see Carlos’ email — which might be difficult for the frail elderly to tolerate.

- What about people younger than 50 who have had shingles? While it’s understandable that they might be interested in the vaccine, it’s not been tested in people under 50, and is not formally recommended in this group. Reassure them that recurrent shingles is actually quite rare, especially within the first few years of an attack.

- My patient never had chickenpox. Should they still get the zoster vaccine? Generally yes. For people born in the U.S. before 1980, essentially all have latent infection with varicella zoster virus — they either had a mild case of chickenpox or don’t remember having it. There might be a small fraction of people over 50 who never had chickenpox, test negative for antibody, and don’t want to risk the side effects of the vaccine. For them, consider the vaccine optional! (Many would recommend the chicken pox vaccine instead.)

- How long after a case of shingles should my over-50 patient wait before getting the vaccine? No one knows. But since active zoster boosts a person’s immune response, it makes sense to wait at least until the current episode has completely resolved. I then add some additional time derived from the sophisticated ID time machine calculators. “At least 6 months” sounds reasonable, doesn’t it?

- We had a shortage of the vaccine, now it’s now been more than 6 months since some of our patients had their first dose. Do they need to start over? Fortunately (for many reasons), no. Just give it when it becomes available.

- Speaking of the shortage, what’s going on? Because of high demand for the vaccine, there have been widespread shortages of RZV ever since the vaccine became available. While these seem to have eased somewhat, especially in the last 6 months, not all practices or clinics or hospitals have it in stock. Fortunately, there’s a handy vaccine finder tool that I hear is quite reliable for pharmacies that offer the vaccine. Many hospital-based clinics also have it (we do).

- Should I still give the new vaccine to people who got the old one? Definitely — not only is the RZV vaccine more effective, but that original live-virus vaccine (Zostavax) becomes less effective over time, and works less well when given to older patients, especially those over 70. If your patient got the live virus vaccine more than 6 years ago, they may not have any residual protection at all.

- I hear the side effects are pretty bad — could they be worse than shingles? While no doubt the new zoster vaccine causes more side effects than most other vaccines, the clinical trials showed that serious side effects — those leading to death, hospitalization, need for urgent medical care — were no more common in vaccine recipients than in those who got placebo. Educate your patients that they might experience arm pain, fevers, fatigue, and myalgias and that these symptoms could be bad enough to have an impact on their daily activities. (This happened in 17% of study participants.) What this means practically is that I don’t recommend giving the zoster vaccine the day before a major life event, travel, or a demanding job requirement. And no harm taking a dose of acetaminophen or ibuprofen for symptom control.

But let’s go back to Carlos for a moment, and how these side effects he experienced compare to herpes zoster:

And to be clear, Shingrix side effects way milder than having shingles!

Completely agree! My experience — arm pain (check), fatigue (check), myalgias (check), and low-grade fever (check). But it was all over in a day, I promise.

And with the acknowledgment that we ID doctors see cases of zoster on the more severe end of the disease spectrum, we have all seen shingles accompanied by a host of really nasty complications. These include encephalitis, stroke, facial nerve paralysis, corneal involvement, vertigo, bacterial superinfection, and, most commonly, disabling unremitting pain (post-herpetic neuralgia) — pain for which there is often little effective therapy.

So the simple answer to the last question — are the side effects from the vaccine worse than shingles? — my answer is an emphatic no! I still strongly recommend it for my patients, colleagues, and friends of a certain age.

And look, my colleagues agree:

Hey #IDTwitter and #primarycare, doing a piece on the recombinant zoster vaccine (RZV, Shingrix), interested in your experience (clinician or recipient). It's more "reactogenic" than most vaccines, but has this changed your practice? @CarlosdelRio7 https://t.co/MXn40PG8k9

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 13, 2019

Back to the Summer of ’69 (the real one) …

(H/T, as always, to the incomparable Immunization Action Coalition site for clear, helpful information.)