An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

April 1st, 2022

As the World Around Us Moves On, We ID Docs Just … Can’t

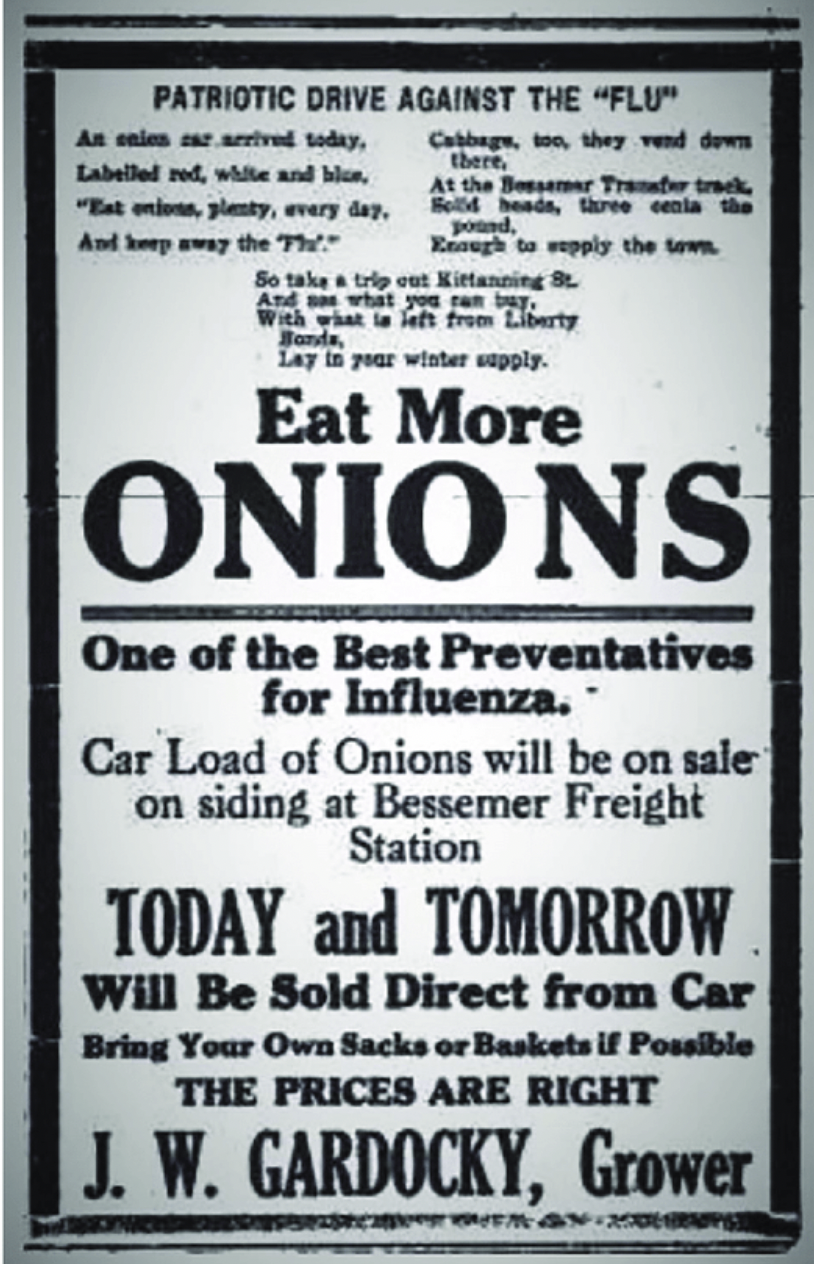

Cheaper (and tastier) than ivermectin — and a whole car load!

Something quite remarkable happened as Omicron tore through the United States in December and January.

Despite triggering a record number of cases — which should have made people more concerned about COVID-19 — Omicron paradoxically did the opposite. It made most of our country decide to move on, even parts famous (or infamous, depending on your view) for being careful. Just to live with this COVID thing — ending vaccine mandates, leaving the masks at home, going back to restaurants, gyms, large parties.

Hey, I get it. When facing something so contagious, something that easily broke through our vaccines, something that even extremely cautious people ended up contracting, we might start having that “what’s the use?” feeling.

Time to get back to normal. Shrugs. Even as cases (and hospitalizations) increase in Western Europe, this relaxed attitude prevails, prompting Dr. Walid Gellad to wonder, Why is everyone so chill?

I’m convinced a major amplifier of this casual response is the reduced per-case clinical severity of Omicron, largely due to partial existing immunity from vaccination, prior infection, or both. This lower severity on an individual level means everyone knows — or experienced themselves — cases that were quite mild.

Typical statements uttered by patients, colleagues, friends, acquaintances during the Omicron surge:

“Felt like a cold.”

“If it weren’t for my positive rapid home test, I still would have come to work.”

“Had one day of feeling blah, then mostly it was lots of nasal congestion.”

“I can’t believe he [referring to a school-age kid] tested positive, he’s as active and energetic as ever.”

“You’ll never believe this, but she [referring to an older family member in a nursing home] tested positive, and we just got off a Zoom call — she seems fine!”

But here’s the problem — the denominator of cases was so ginormous during Omicron that it still led to a staggering number of hospitalizations and deaths. Way more than from flu, even in a bad flu year. People who had weakened immune systems, had multiple medical problems, were still unvaccinated, or were just unlucky to get a really bad case still experienced severe disease. And some fraction of all these Omicron cases will be left with long COVID, evaluation and treatment of which remains in its infancy.

Some people may not have seen this numerator. But believe me, we sure felt it, as did our hospitals. We still needed the ICU beds for some COVID patients, still adhered to strict infection prevention measures for everyone with a positive COVID test admitted to the hospital, still struggled to clear hospital workers (who came down with Omicron just as much as everyone else) for return to work.

You need no further evidence of how the Omicron surge disrupted patient care than to observe how many hospitals delayed non-essential surgeries. Not only is elective surgery important for good patient care (ask anyone who had their surgery delayed), but also this is the most remunerative service provided by most hospitals in the United States. As a result, I doubt there’s a single hospital in the country that didn’t have a negative balance sheet during Omicron.

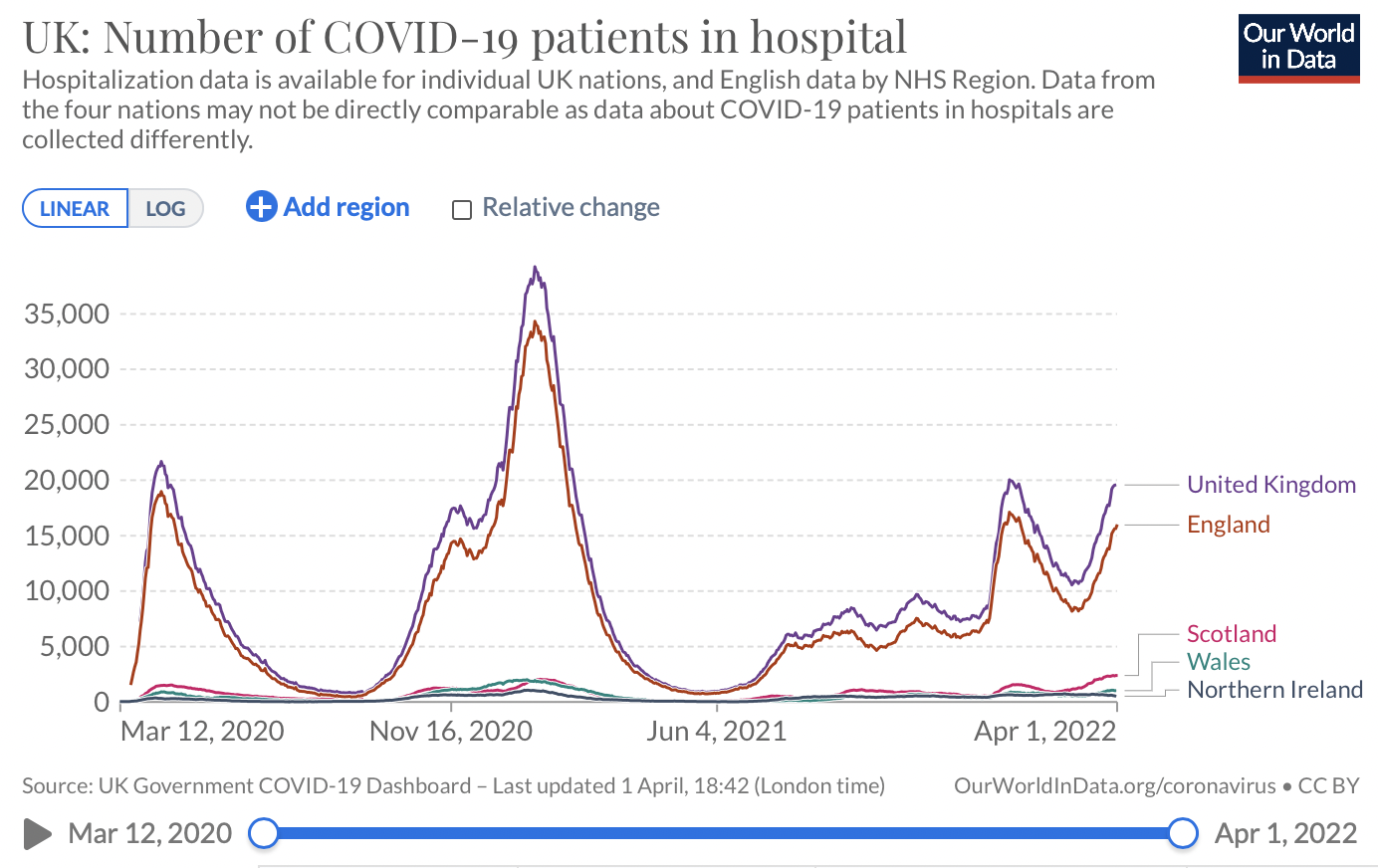

Now, as we ID docs watch what happened in Western Europe, we can’t help but squirm. “What happens in the U.K. most certainly DOES NOT STAY in the U.K.” should be public health’s advertising slogan for what comes next in the northeastern USA:

ourworldindata.org/grapher/uk-covid-hospital-patients

Already we see the trend starting, with the increase in wastewater concentrations of the virus in most regions, a rise in the reported test-positivity rate, and a slow creep up in people testing positive among those hospitalized. All this generates more calls about exposures in the workplace and at home, about how to get nirmatrelvir, about the latest monoclonal antibody taken down by viral evolution, and this week a zillion people asking about whether to get a booster now, wait until just before a fall surge, or wait for a variant-specific vaccine.

You know, the pandemic life of an ID doctor.

So while much of the rest of the population has moved on, forgive us ID docs if we remain nervous Nellies. We can hope that case numbers will be lower during the BA.2 Omicron surge — and they might be — but we can’t count on it.

Now, I just have to get that smell of onions out of my car …

March 22nd, 2022

What Have We Learned from the Pandemic So Far?

The title slide of an upcoming talk. You can see I’ve made great progress.

Dear Readers,

I need your help.

Recently one of my colleagues reached out and asked if I could give a talk to his research group.

“Just give one of your canned Covid talks,” he said.

Ha.

Needless to say — but I will say it anyway — he’s not an ID doctor. Otherwise he’d know that, as I’ve said before, talks on COVID-19 become outdated as soon as you click the little save button (it’s a floppy disk icon) on your PowerPoint program.

As a result, there’s no such thing as a “canned Covid talk” because you need to update them constantly. The field is constantly changing.

(Small aside here — how long will that particular save icon be up there at the top of Microsoft Office programs? After all, people stopped using floppy disks in the late 1990s. My crack research team revealed that companies completely stopped making them over a decade ago.)

How quickly do these COVID talks become outdated? Much faster than floppy disks. I’ve lectured multiple times on COVID-19 over the past 2 years, to a variety of medical and non-medical learners, and thought it might be interesting to see what a talk looked like just 6 months ago, back in September 2021 — an eternity in COVID time.

(I’ve done talks since then, too, but let’s look at 6 months ago for the full effect.)

It included these obsolete topics that one would be hard-pressed to include in a talk today:

- The Delta variant — see you later!

- The monoclonals casirivimab plus imdevimab and bamlanivimab plus etesevimab — remember those? Can you pronounce them yet? If not, you’re probably spared having to learn.

- The debate about whether remdesivir works — not much of a debate anymore, provided it’s started early enough.

- The latest on baricitinib — now a widely accepted tocilizumab alternative.

No mention of nirmatrelvir or molnupiravir or PINETREE or Evusheld or bebtelovimab or interferon lambda. And definitely no Omicron, that was our “gift” during the holiday season, 2021.

It did include the FDA’s admonition on ivermectin, always good for a few chuckles:

https://twitter.com/US_FDA/status/1429050070243192839?s=20&t=Y2xezMoy7Zau9zJpt1YX9A

That one never gets old, and might stick around for a while in upcoming talks.

Frustrated by the constant churning of content in these COVID talks, I offered my colleague a somewhat different topic, namely:

COVID-19: Lessons Learned (So Far)

… which is why I’m reaching out to you, loyal readers of this site, for help. In a classic case of “be careful what you wish for,” I now realize that this is a gargantuan topic, one spanning pretty much every discipline under the sun. A comprehensive review would take hours (not 50 minutes, with 10 minutes for questions). Frankly, it’s a good topic for an entire PhD thesis.

Overwhelmed, I’ve already checked in on social media — here’s one great response, from Dr. Darcy Wooten:

Life is short, pandemics help expose structural inequalities, rigorous science matters, politicizing medicine is harmful, and vaccines are amazing. In our darkest hours we must hold on to hope. We must keep going.

Impressive what some people can do within the 280 character limit on Twitter! I offered her the opportunity to give the talk in my place, but she declined. Quite understandable — she lives in San Diego, a long way from the Longwood Medical Area. Plus, it’s still freezing here in Boston.

But seriously — what would you include in a talk with this title?

Let me know in the comments. And you can go longer than 280 characters.

March 7th, 2022

How to Induce Rage in a Doctor

Advertisement for Hunt’s Remedy, which cured all diseases but did not require a prior authorization.

If you’re wondering how to make a doctor angry — really, really angry — read on. Because asking us to justify treatment decisions to insurance companies and their pharmacy benefit managers must rank right up there with the greatest tortures of practicing medicine in this country.

Mind you, this isn’t just about my patient, or about me — such infuriating events take place innumerable times in countless offices, hospitals, and clinics around the country every day, wasting everyone’s valuable time with no evidence whatsoever that they improve the quality of care.

Such struggles are an inevitable part of a healthcare system that values profits over people. The debates require a veritable army of staff on both sides to navigate what should often be very straightforward treatment issues.

Here’s a timeline of what happened. It’s Part 2 of the case presented a couple of weeks ago, which appeared with the patient’s permission (certain details changed).

February 6: Patient notifies me he needs a corticosteroid injection for back pain, which is contraindicated with his current HIV therapy due to a potentially serious drug interaction. We set up a video visit to discuss alternative HIV treatment options.

February 7: Televisit. I explain some treatment options, which I outline as bictegravir/TAF/FTC, dolutegravir/3TC, or doravirine plus TAF/FTC. He opts for the doravirine option based on side effects from previous treatments. Prescription sent to pharmacy.

I mention to him that doravirine sometimes requires a prior authorization. I also tell him that with his employer-provided insurance, it most likely will be fine. After all, the guy has a high-powered job in a very well known organization. He must have good coverage.

Furthermore, while HIV treatment remains quite expensive, none of the alternatives I’ve offered costs significantly more than what he’s currently receiving, and some cost less — at least based on the prices available to us.

Ha. Not so fast.

February 10: Message from patient that his pharmacy told him doravirine wasn’t covered. Needs a prior authorization.

I ask our pharmacy team, which consists of pharmacists and pharmacy techs hired for this express purpose, to help with it. They send it in, along with my office note from the televisit which justifies the reason for the treatment change.

February 14: I hear from the pharmacy team — prior authorization has been denied. Oh, and there’s this message:

Alternative Requested: PIFELTRO [doravirine] is NON-FORMULARY. MUST USE EFAVIRENZ, NEVIRAPINE, EDURANT. Call xxx-xxx-xxxx.

Well, this is a joyful Valentine’s Day present. They obviously don’t know his medical history, or much about HIV treatment. Why can I make this assumption?

- Efavirenz caused severe side effects years ago — he can’t take that.

- Nevirapine is not recommended in any treatment guidelines anymore, especially in people (like my patient) with high CD4 cell counts, as this increases the risk of severe hypersensitivity — he can’t take that.

- Edurant (rilpivirine) should not be given to people with low stomach acidity since it won’t be fully absorbed — he can’t take that.

I’ve always wondered — what if we followed these directives, and something truly terrible happened? After all, there are people who have died from nevirapine hypersensitivity, either from toxic epidermal necrolysis or fulminant liver failure or both.

Would the insurance company bear any of the blame, or legal risk? Would they care? I know the answer, sadly.

February 15: I call the phone number, which takes me to the pharmacy benefit manager. It’s the Giant-est of the Giants. How do annual revenues of more than 30 billion dollars sound? Pay for plenty of doravirine with that.

Phone tree. Then hold music. A warning about high call volume and long wait times. Then a person. Below a sampling of the dialogue.

Pharmacy Benefit Manager person #1: Hello, you’ve reached Brett. May I have the client’s member number?

Me: I don’t have it. I have his name and date of birth.

PBM person #1: OK, I’ll take that.

[pause while they look up the record]

PBM person #1: It says here the prior approval was denied. Pifeltro is non-formulary. You must use [pauses] EFAVIRENZ, NEVIRAPINE, EDURANT. [Difficulty reading the HIV drugs implies no knowledge of HIV medicine.]

Me: I know that — this is why I’m calling. But he can’t take any of those.

PBM Person #1: Do you want a clinician-to-clinician consultation?

Me: Yes. That’s why I called — this is the number we were given.

PBM Person #1: OK, let me transfer you.

[Hold music. Another warning about high call volumes and long wait times.]

PBM Person #2: Hello, you’ve reached Blake. May I have the client member #?

Me: I just gave that information to the previous person. Didn’t they pass that along to you?

PBM Person #2: Sorry, no.

Me: I have the name and date of birth, not the client #.

[Information given again.]

PBM Person #2: It says here that your prior approval was denied. You must use [pauses] EFAVIRENZ, NEVIRAPINE, EDURANT [more difficulty pronouncing the HIV drugs].

Me: That’s what the last person said to me, and I already know that. My patient can’t take any of these drugs. This is supposed to be a peer-to-peer consultation.

PBM Person #2: They sent you to the wrong number. I can forward.

[Hold music. Long hold.]

PBM Person #3: Hello, this is Bobby. May I have the patient’s name and client #?

Me: I only have the name and date of birth.

[Information given again. Third time, but who’s counting.]

PBM Person #3: I found the record. The Pifeltro was denied.

Me: Yes, Bobby, I know that, this is why I’m calling. Hoping you can help me. I’m an ID/HIV specialist in practice since 1992, and I’ve known this patient since 1996, including his full treatment history. The recommended alternatives are contraindicated — he can’t take any of them.

[Long pause.]

Me: Hello, do you need any further information?

PBM Person #3: I’m sorry, doctor, but I am not authorized to approve this drug.

Me [more than a little annoyed at this point — in fact here’s a good description of how I looked]: Why then am I speaking with you? This is the phone number I was advised to call. Are you a clinician? Do you have any knowledge of HIV treatment? Do you have access to the notes that were submitted for this claim?

PBM Person #3 [sounds like Bobby is now driving a car while speaking with me]: I’m sorry, Doctor. I am not authorized to approve this drug. If you want to appeal, or the patient wants to appeal, they will need to directly contact his insurance company with an appeal letter.

So why did all this happen? Why did Brett, Blake, and Bobby each fail to help my patient get his prescription covered?

It all starts with the relatively high cost of HIV treatment to begin with — a cost that has increased over 30% since 2012, a rate 3.5 times faster than inflation. Unlike most other industrialized countries, where government payers gather disease experts to review treatment options, then work with the pharmaceutical companies to arrive at a cost, such deliberations here are explicitly blocked and remain controversial.

With antiretroviral therapy so costly, insurance companies enlist the PBMs to negotiate what treatments get covered, what don’t, and how much they’re going to cost. It’s all done behind closed doors, in exchanges that one insider told me are “brutal.” As concisely (and accurately) stated in the opening to this recent perspective, “Prescription drug prices in the United States are opaque.”

The PBMs also sometimes direct where patients can most easily get their prescriptions filled (which may be the same companies, imagine that), and discourage dispensing of less expensive (but not negotiated) products.

If you think this clandestine process is ripe for distortion, obfuscation, and misuse of power, you’d be absolutely right. The lack of transparency means my patient and I have no way of finding out why doravirine isn’t covered — just that it isn’t.

But one thing I can state with 100% confidence — the refusal to cover my patient’s doravirine prescription has nothing whatsoever to do with improving the quality of his care, or following treatment guidelines, or really anything related to his health at all.

It was all about money. And that is sad indeed.

Hey, two more entries for the timeline:

February 25: Received information about the appeal process, and wrote the letter.

March 7: Still waiting …

(Thanks to brilliant colleagues Drs. Aaron Kesselheim and Ben Rome for reviewing this post. And to Dr. Glaukomflecken for making us laugh and cry at the same time.)

February 22nd, 2022

A Personal Tribute to Dr. Paul Farmer — Who Made Everyone Feel Important

Paul Farmer’s unexpected death this weekend has all of us who knew him reeling. This just should not happen to someone so generous, so important, and so visionary about helping others — especially others who, due to being born in impoverished life circumstances, can’t help themselves.

Paul Farmer’s unexpected death this weekend has all of us who knew him reeling. This just should not happen to someone so generous, so important, and so visionary about helping others — especially others who, due to being born in impoverished life circumstances, can’t help themselves.

This is not fair at all. We’re heartbroken.

The tributes will deservedly be pouring in over the next few days about his global impact, so here’s a very personal one. One of Paul’s great talents was making you feel important.

It didn’t diminish the experience one bit that he made everyone feel important — when he was talking to you, looking at you, he had you front and center in that big generous heart of his, and everyone else drifted away. These important people could include the President of the United States, the patient who was the fifth consult of a busy day on the inpatient ID service, the members of the band Arcade Fire, or a person with severe tuberculosis in rural Haiti. All are VIPs to Paul.

Several years ago, I cited this supernatural ability of Paul to make everyone he met feel like they mattered when discussing his skills as a doctor working here in Boston. Didn’t matter whether you were a patient, or a consulting surgeon with a short attention span, or a green medical student, or a hospital transport person. Everyone felt this from Paul, regardless of his skyrocketing fame.

One of these important people was my friends’ daughter, Lily. When she was 12, she read Mountains Beyond Mountains and, like countless others, derived inspiration from Paul’s career.

I told Paul about Lily’s enthusiasm for his work. Immediately he offered to sign a copy of his book Pathologies of Power, and told me to give it to her as a present. He inscribed it “For Lily, for later” (he knew it wouldn’t be easy reading for a 12-year-old), and he included his email address (of course). I told him I’d pay for the book, but he flat-out refused.

After I gave her the book, she dropped by one of our post-graduate courses that featured Paul as a speaker to thank him. More important was that he gave her time to talk about his work, and what she wanted to do with her life. She was truly starstruck, and used the experience to inspire a wonderful speech at her bat mitzvah.

(For those who haven’t heard bar or bat mitzvah speeches, they usually reflect pre-adolescent obsessions that then are jerry-rigged by the rabbi into something more generous or religious. Mine probably had something to do with baseball and model rockets — not health equity.)

Later, I thanked Paul for being so generous with both his book and, especially, his time with Lily. (This guy could be pretty busy, you know.) I told him that she featured his work and their meeting in her bat mitzvah speech, and how inspiring his dedication to helping the poor was to her.

Paul would take no credit (he never did) — but he did email me this:

Please send Lily my congrats on her bat mitzvah. I’ll bet that she’s going to talk about social justice and remaking the world for a long time. We need people like her on this planet.

The story doesn’t end here. Each time I saw Paul over the next few years, in addition to catching me up on family and work and whatever latest crisis he and Partners in Health were tackling, he’d smile and ask:

“How’s Lily?”

He’d be pleased to know that she’s currently lobbying at the state house on behalf of non-profit organizations in Massachusetts. It’s not a stretch to say that Paul’s influence led her to choose a career in public policy.

And no, he’d never forget her name. That’s just Paul for you. We’re all important — even when there’s nothing in it for him.

Not a bad lesson for how to live life, is it?

February 12th, 2022

The Rise and Fall of Ivermectin — 1 Year Later

Cheese consumption and death from bedsheets are highly correlated.

Here’s a confession few board-certified ID doctors will make — there was a brief period when I thought ivermectin could very well be an effective treatment for COVID-19.

It wasn’t when the in vitro data first came out. Therapeutic concentrations were not achievable in humans.

Nor when the anecdotal reports started pouring in, and sometimes making news. A former colleague of mine, a smart and clinically active person practicing in the Midwest, contacted me in late 2020 telling me that they acted as the primary medical consultant for a nursing home. Since they started using ivermectin, no patient had died or even been hospitalized from the disease. OK, a hopeful observation, but not proof.

Not when the figures appeared correlating ivermectin use and lower death rates from COVID-19 in some countries, mostly from tropical regions in South America and Asia. These figures always reminded me of these spurious (and often hilarious) correlations. Did you know that per capita cheese production correlated strongly with the number of people who died by becoming tangled in their bedsheets? Who knew? And what’s the mechanism?

And certainly not when these folks started pushing ivermectin with an enthusiasm that is frankly religious in intensity. This group’s treatment “protocols“, with their hodgepodge of antimicrobials (including ivermectin), immunomodulators, and vitamins — the kitchen sink approach — strain credibility.

Nope — my moment of greatest hope for ivermectin came just over a year ago, when Dr. Andrew Hill presented results from a meta-analysis of several randomized controlled trials, a presentation he would later also give to the NIH Guidelines panel. Andrew is a well-respected clinical researcher, someone well-known in the HIV research world.

In his analysis as first presented, the risk-ratio for mortality with ivermectin was 0.17 (95% confidence interval 0.08, 0.35), an 83% reduction in risk for dying. Outcomes for other endpoints (time to viral clearance, time to clinical recovery, duration of hospitalization) also favored treatment over controls.

Hearing these data, I reached out to Andrew to discuss his findings, and he generously discussed them with me. He acknowledged that the data were incomplete, but remained strongly suggestive of clinical benefit. Furthermore, he’d been in direct contact with the researchers who conducted the largest of these studies. They repeatedly reassured him that the data were sound.

I subsequently summarized my thoughts here in a post entitled, “Ivermectin for COVID-19 — Breakthrough Treatment or Hydroxychloroquine Redux?”; writing:

My take-home view? The clinical trials data for ivermectin look stronger than they ever did for hydroxychloroquine, but we’re not quite yet at the “practice changing” level. Results from at least 5 randomized clinical trials are expected soon that might further inform the decision. NIH treatment guidelines still recommend against use of ivermectin for treatment of COVID-19, a recommendation I support pending further data — we shouldn’t have to wait long.

What happened next? I offered Andrew the chance to submit the meta-analysis to Open Forum Infectious Diseases, which after conducting some additional analyses, he kindly did. Remember, at this time in early 2021, we had no readily available effective outpatient treatments COVID-19. Something inexpensive, safe, and widely available certainly would be most welcome.

After peer review and some revisions, with Andrew and his team reducing the survival effect size for ivermectin to 56% (still highly significant) due to some additional studies, we accepted the paper. We simultaneously solicited a thoughtful editorial from my Boston ID colleague Dr. Mark Siedner, entitled “Ivermectin for the Treatment of COVID-19 Disease: Too Good to Pass Up or Too Good to Be True?”

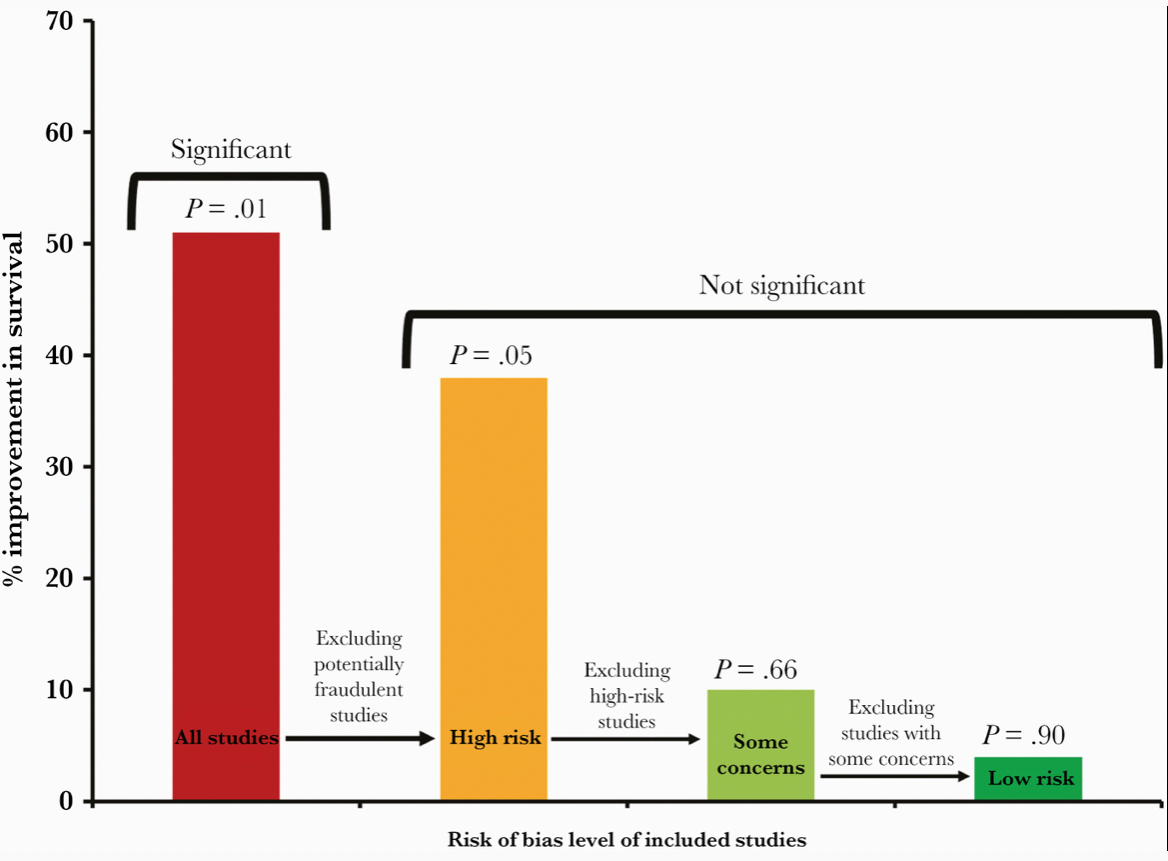

Well, we now know that the second part of Mark’s brilliant title turned out to be the case — too good to be true. Many of the studies on which the meta-analysis was based were highly flawed, and one was outright fraudulent. The fake data problem came to light just shortly after the meta-analysis appeared in print.

To his credit, Andrew promptly contacted me when the news broke. He immediately offered to retract the original paper, and even better to submit a detailed analysis of what went wrong.

This revised paper has just been published, entitled “Ivermectin for COVID-19: Addressing Potential Bias and Medical Fraud.” It includes this extremely telling figure, which shows how the effect size of ivermectin on survival drops to meaningless with exclusion of the fraudulent and potentially flawed studies:

Read the full paper! But if you don’t have time, here’s the lesson:

These revised results highlight the need for rigorous quality assessments, for authors to share patient-level data, and for efforts to avoid publication bias for registered studies. These steps are vital to facilitate accurate conclusions on clinical treatments.

Indeed. And for whatever role I played as an editor in sustaining the confusion — and sometimes heated conflicts — over this potential treatment for COVID-19, I deeply regret it and apologize. I hope this post, and even more, Andrew’s revision, explain what happened, and hope we all can learn something from this mistake. Certainly I did.

Meanwhile, several large placebo-controlled trials continue to test ivermectin for COVID-19 treatment in outpatients. It still might do something (though at this point I’m not very hopeful). At least one of the studies — COVID-OUT — is fully enrolled, and ACTIV-6 is far along, so more data will be forthcoming soon.

Will these results be enough to quell the controversy about whether ivermectin has a role in treatment COVID-19, settling the issue once and for all? Let’s hope so.

February 4th, 2022

Prior COVID-19 Is No Guarantee of Immunity

19th century apothecary advertisement, Lowell MA. Product has fewer drug interactions than ritonavir-boosted nirmatrelvir.

I’m no immunologist — a fact made vividly obvious to me several years ago when asked to teach a weekly medical student section that included cases and problem sets. The challenge was that the course combined immunology and microbiology.

I was on much firmer ground with the microbiology than the immunology, the latter often a wonderfully complex and mysterious system.

So why, then, am I about to wade into perilous waters and write about something very much immunology-related, a subject I’ve already confessed to being an amateur at? Because to us ID specialists, the immune system plays a critical role in how our bodies respond, clear, and protect us from various infections. We may not be true experts, but it’s highly relevant to what we do.

Additionally, I’m watching a debate unfold among ID colleagues, public health officials, epidemiologists, the lay public, politicians, and yes, even advanced degree-holding immunologists. It’s a debate about a critical issue facing the globe as we march on to the third year of the pandemic.

Namely, does infection with SARS-CoV-2 confer protective immunity?

Views range from “yes, certainly” to “maybe, sometimes” to “it depends” to “absolutely not.”

Everyone can cite their favorite study to back up their opinions — whether it’s an epidemiologic analysis of reinfection rates, or the cases of reinfection after prior COVID-19 that are less (or more!) severe than the first, or an in vitro study demonstrating robust (but then waning!) antibody responses, or how cells from people with prior infection continue to mobilize protective cytokines, or contrarily how prior infection inhibits these helpful cellular responses.

Many of the people lining up on opposite sides of this debate are smart, have impressive credentials, and aren’t shy about expressing their opinions — hence sparks do fly.

This doesn’t help resolve the issue, because of course they cite mostly the scientific studies and opinion pieces that support their views.

So for the price of subscribing to this blog, here’s my non-immunologist’s take, and warning — it’s a messy one with no precise answer:

Prior infection confers some degree of protective immunity. It varies from person to person, depends on the severity of the disease, with “just right” being more protective than mild or severe illness. (Cue classic Goldilocks analogy.) It’s not durable, is not guaranteed, and certainly isn’t going to lead to herd immunity on its own anytime soon.

Nope, no herd immunity by April 2022, just like it didn’t happen by April 2021.

Incomplete immunity conferred by prior episodes of COVID-19 is one critical reason that studies of populations continue to show that the unvaccinated have a markedly higher rate of hospitalization and death than the vaccinated — even though prior infection is becoming more common.

Two years into the pandemic, with major population surges, this remains an undeniable fact everywhere it’s studied — even though a higher and higher proportion of the unvaccinated have already had the disease. If prior infection were strongly protective, the gap between vaccinated and unvaccinated in risk of hospitalization would decrease over time. It hasn’t.

Omicron only exacerbated this reinfection issue, with many of us seeing or hearing about patients with repeat infections, sometimes quite quickly after a first infection:

https://twitter.com/TheBlondeRN/status/1489608641858654219?s=20&t=bairQyDjErYe4NJziFpC9Q

Indeed, if we asked a group of primary care clinicians, emergency room folks, and other front-line providers to raise their hands if they had cared for or heard of people with more than one episode of COVID-19 — usually less severe, but sometimes more — 100% would have their hands up.

Incomplete protection from prior infection isn’t what any of us want to hear. But as we’ve learned again and again, wanting something from this virus doesn’t make it happen. The other night, someone in my family asked me whether now, as Omicron nabbed so many of us who previously escaped, can we at last move past this pandemic and get back to normal?

It’s such a good question!

I just wish I had a more reassuring answer.

In the meantime, let’s get everyone vaccinated, even those with prior infection. It’s a much more reliable way of getting protected, especially from severe disease.

January 28th, 2022

Required Learning Modules and How to Make People Learn

Mandatory learning modules were different in the 19th century.

Like thousands of others who work in my organization, I’ve just finished a stultifying annual task — several hours of required online learning modules that must be completed to keep my job.

How much do we look forward to them? Think annual car inspections, or tax returns, and multiply the boredom factor several-fold.

You might not be surprised to hear that the due date is … today.

You also might not be surprised to hear that as part of the process, I aggressively sought out ways to multitask while the videos ran in the background — cleaned my desk, filed papers, did low cognitive demand patient care tasks, repeated some arm strengthening exercises to prevent tennis elbow, checked the latest weather forecast (ugh).

Since the clever folks who make these modules programmed them to stop running unless the video or slideshow is the active window, could I have been the only one who opened the program on a second computer? Doubtful.

In short, these “learning modules” offer a prime example of how difficult it is to make people learn things when they’re in no mood to learn.

Without exception, everyone I know races to the finish, delighted to find their to-do list empty. Even this doc, despite his admirable quest for learning and growth. Find an elective in the catalog! You bet.

https://twitter.com/kkidia/status/1487036908039544833?s=20&t=IYIQhUl6HbTSF7V9-RHTzw

It’s not that the topics in these required modules are unimportant — anything but. Patient confidentiality, racism in the workplace, infection control, employee harassment, managing chemical spills and fires, what to do if there is an armed intruder in the hospital.

Sure we make fun of the fire extinguisher trivia required to pass the fire safety module (“The canister with a thin hose which contains water is a Type A fire extinguisher, used for ordinary combustibles”), or the incredibly obvious statements (“Chemical exposures can be dangerous”). Tornado safety measures will never be as relevant in New England as they are in Oklahoma.

But read that list from the above paragraph again. It’s important stuff!

No doubt organizations must, for their accreditation, demonstrate that their employees are dutifully notified about these issues, explain when and how to get help, and provide a list of resources where a person can go to get more information. Given the extraordinary range of activities and backgrounds in hospital workers, this cannot be an easy task. One size most certainly does not fit all.

So I’m sympathetic about the challenge.

I just think that from a pedagogical perspective, there has to be a better way — a less painful way — to learn the material, one that would allow the hospitals to check this box.

Maybe this owl can come up with something while keeping her egg warm. Lots of thinking time.

She can even use the time to finish her Healthstream modules.

January 18th, 2022

Novak Djokovic Thinks He Can Play by His Own Rules — Australia Says Think Again

YWCA Health Poster, 1920s.

There was a truly talented kid on my ninth grade basketball team — let’s call him Robbie G.

He was a terrific player, fast and confident on the court, always eager to play, and just brimming with enthusiasm for the game. Every time he scored, the team and crowd (small as it was) buzzed with excitement and shouted his name. A joy to watch.

But — and this might surprise you based on my introduction so far — Robbie was an immature jerk.

The rules didn’t apply to him. He did what he wanted during practice, and with few exceptions, the coach just shrugged and let him.

More from Robbie: He jokingly (ha ha) taunted the less-good players on the team, which meant just about everyone received some knocks. I certainly learned to avoid him both in the locker room and on the bench (where I spent most of my time during games).

When our team lost, or even worse — when he met his match in an opponent who guarded him closely — he became a petulant baby. These were not good times to cross his path, or heaven forbid try to comfort him.

This behavior carried over to non-basketball settings, and in school he was a terror. Sometimes a bully, sometimes only a disruptive nuisance, he quickly made his his presence known to everyone nearby — the effect amplified by a small group of less-talented (and equally annoying) sycophants.

I couldn’t help but think of Robbie while reading the news about Novak Djokovic, currently the best tennis player in the world. He can’t play in the Australian Open this year since he’s refused COVID-19 vaccination, and the Australian government will not approve his visa.

Like Robbie’s artistry on the basketball court, only scaled up to the adult and professional level, Djokovic’s tennis is a sight to behold. Here, let sports writer (and avid tennis fan) Joe Posnanski describe it (I’d never do it justice):

…He blends the most incomprehensible array of weapons — blazing speed, unmatched anticipation, a mathematician’s sense of angles, a tireless hunger to return every shot, a dream of a backhand and the best return of serve in tennis history — and turns every match into an art exhibit.

But … see what I wrote up there about Robbie, and the rules not applying to him? This fits the Djokovic affair perfectly. It also fits that Djokovic gave an interview and posed for a photoshoot for a media group after exposure to COVID-19 and testing positive by PCR.

I feel fine. Some of my tests were negative. See, the rules don’t apply to me.

High-level athletic ability facilitates this I-know-best view of the world. Here’s the recipe: A lifetime of winning. Adulation by friends, fans, teammates, coaches. Intense competitiveness. Suspicion of others. Wanting to beat others.

Mix these all together, and of course a person ingesting this potent brew is going to think they know best for themselves. Each win proves them right, reinforcing the problem.

In fact, we’re so used to hearing stories about rule-breaking behavior among professional athletes — how about football’s Aaron Roger’s definition of ‘immunized’? — that those who express thoughtful and generous sentiments stand out as model citizens. Tennis has two of these exemplars at ready hand, Roger Federer and Raphael Nadal. Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic — the “big three” — have dominated men’s tennis for over a decade.

Says Nadal, with searing accuracy, about the whole Djokovic affair:

If he wanted, he would definitely be playing here without a problem. Everybody is free to make their own decision – but there are some consequences, no?

Bravo. And let the record show that 97 out of the top 100 tennis players in the world are vaccinated. Djokovic, one of the three unvaccinated, refused the vaccine because he thought he could. His rules. The Australian government, citing their rules, said otherwise.

Back to Robbie G. for a moment. Remember, there’s another important difference between my basketball teammate Robbie and Djokovic, one that goes way beyond their relative fame, fortune, and chosen sport.

Robbie was 14 years old. Djokovic is 34.

January 12th, 2022

The Pandemic Life of an ID Doctor — in Graphic Form

Three works of art sit on my father’s desk in his office, gifts from his children from when we were in grade school.

From my brother Ben, there’s a little bear, or perhaps it’s some other burly quadruped — easily a B+ in his art class from the 1960s, likely an A- now with grade inflation.

A graceful ceramic bird represents my sister Anne’s contribution. It’s elegantly taking wing with the kind of naturalistic style one might have found from Bernini himself as a 6-year-old. I can just hear the teacher’s approval as it came out of the kiln — top-of-the-class kind of stuff.

My piece of “art” is a rock with three small shells stuck on awkwardly by Elmer’s glue. Ouch.

In short, in our family Anne got the bulk of the artistic skill (and I got the least — almost zero). Long-time readers may remember her cartoons from our ID caption contests, this figure of the Four States of Clinical Medicine (a particular favorite of mine, so clean), or this Fulyzaq, may it rest in peace.

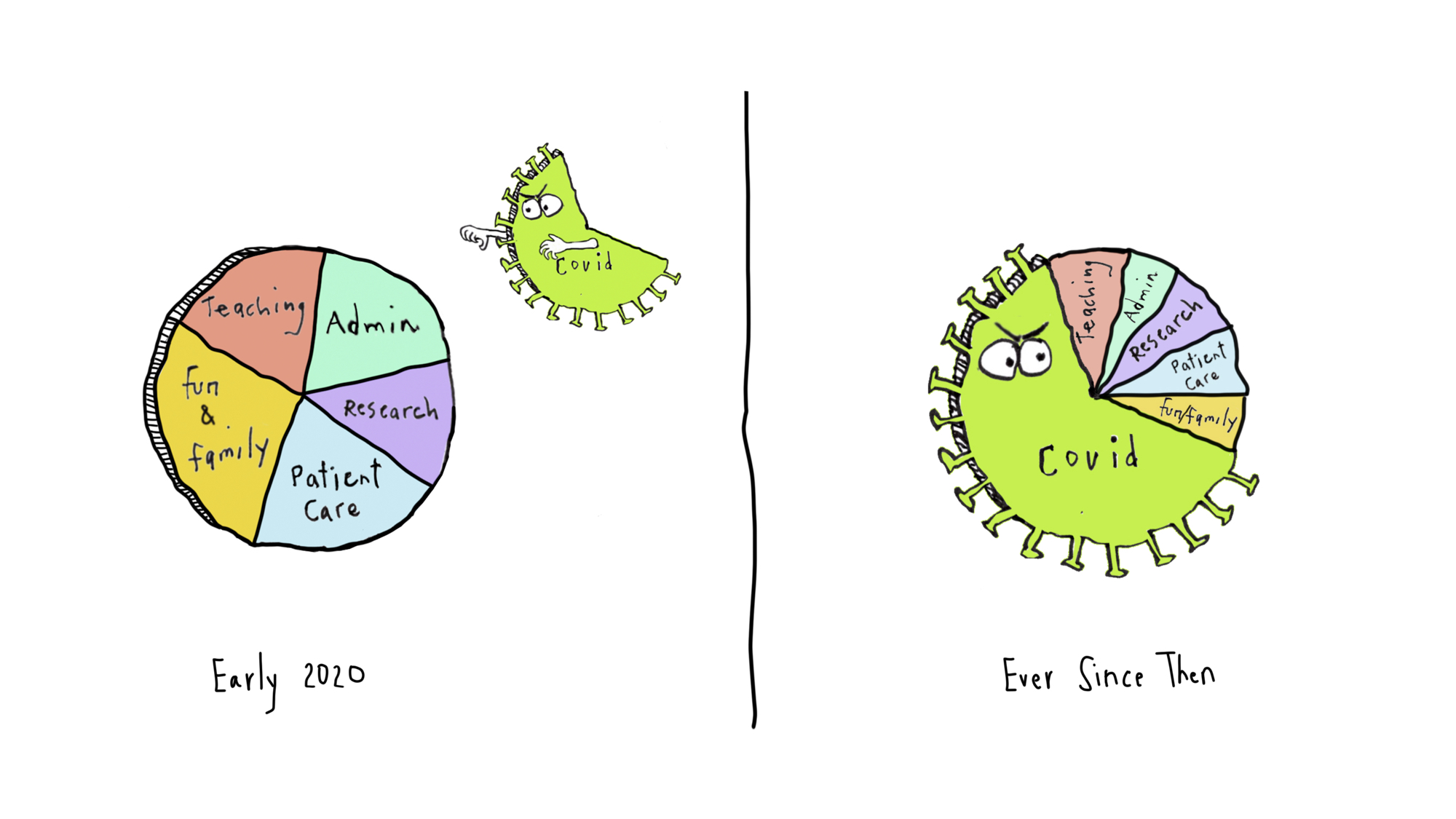

I bring this up now because Anne kindly asked me what life is like for us ID doctors now 2 years into the pandemic.

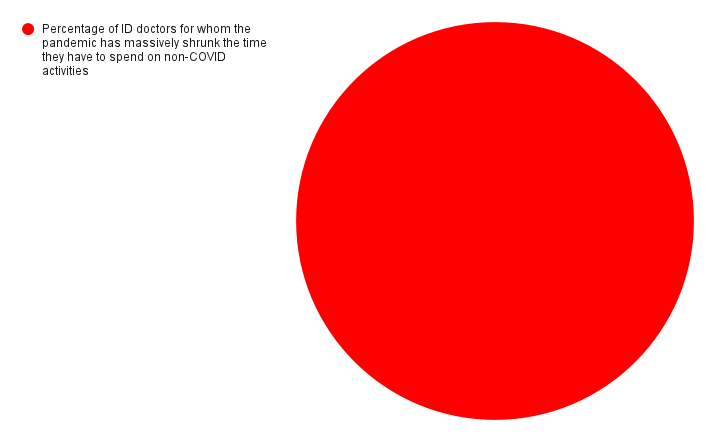

I tried to explain it by saying that our usual distribution of work and non-work activities are constantly barraged by this big bully, COVID-19. If you picture your life as a pie chart, with each slice representing how you spend your time, along comes this scary, gigantic brute shoving everything else aside and making the rest of your life experiences and activities that much smaller.

Anne was kind enough to sketch it out for me — it looks something like this:

The compression of non-COVID stuff is a loss — it’s even more extreme during surges (now), with the COVID part occupying at least 80% of this pie chart. And 90% of our worries and disturbing dream content.

So what are the consequences for other work and life activities? Let’s consider a few, selected at random from my experience and that of my colleagues.

That friendly call to your patient who recently started HIV therapy to give them the good news about their first monitoring blood tests?

That research on molecular mechanisms of drug resistance in shigella?

That quality improvement project on optimal management of Staph aureus bacteremia?

That teaching module for medical students on the diagnostic approach to fever and rash?

And finally, that hike in the woods to the top of a nearby mountain with your family, fully disconnected from work?

All made that much smaller — or delayed or skipped — by this giant piece of pie insensitively hogging space in your life chart. There’s only so much time in a day.

Of course, this is understandable. We’re infectious diseases specialists, after all, and the pandemic is caused by an infection, a virus. And no doubt this is true for other clinicians in various specialties — emergency room doctors, primary care providers, pulmonologists.

But I can guarantee what another pie chart looks like. It’s shows the percentage of ID doctors for whom the pandemic has massively shrunk the time they have to spend on non-COVID activities.

It’s a big circle, completely filled in, 100%. All of us.

Even I can draw that one.