An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

November 29th, 2022

#IDTwitter — Still a Wonderful and Entertaining Place to Learn

Twitter is much in the news recently, mostly for not-good reasons. Rather than rehash-tag (see what I did there?) its various struggles and controversies since the new owner took over, I’m going to let others cover that territory.

Twitter is much in the news recently, mostly for not-good reasons. Rather than rehash-tag (see what I did there?) its various struggles and controversies since the new owner took over, I’m going to let others cover that territory.

Instead, I’d like to go in a different direction, and share how this site remains one of the most valuable tools for learning about ID — and other medical and not-so-medical news.

It’s also a ton of fun. That is, if you’re careful, and know the rules, which I’ll get to in a moment.

First, here’s brief summary of how I figured out Twitter. I’m hopeful by sharing that you’ll consider joining. Plus, the more smart, engaged, and nice people we have on Twitter — people actively communicating about our fascinating field — the better it becomes.

It began for me in 2009, shortly after the tech writer David Pogue wrote about Twitter in the New York Times. He described a chaotic mess with essentially no rules — a place where you could crowdsource solutions to complex problems, or “entertain” people by sharing what you cooked for breakfast, or market your latest business idea, or link a piece of writing you found particularly profound, or show a puppy video that makes you gasp at the cuteness.

Or, all of the above.

But the best part of his piece was this comment:

DON’T KNOCK IT TILL YOU’VE TRIED IT. Of course, this advice goes for anything in life. But listen: even my own masterful prose can’t capture what you’ll feel when you try Twitter. So try it. If you don’t get any value from it, close the window and never come back; that’s fine.

As a big Pogue fan, and with nothing to lose, I thought — why not? So I signed up. Then, after trying it for 10 minutes or so, and remaining utterly baffled, I then just ignored it completely — for the next 6 years.

What changed?

Several things, happening all around the same time. First, I noticed that both some of my younger colleagues — and especially the medical residents and ID fellows — could cite recently published or presented research I hadn’t yet heard. Where’d they get this cutting-edge information? They all said one place: Twitter.

Here’s a recent example of a clinical trial published in JAMA that totally would have been off my radar screen for quite a while without Twitter, posted by the invaluable account @ABsteward:

https://twitter.com/ABsteward/status/1577318206993092610?s=20&t=avV7L4-RD1LpzYW9A3Yunw

Second, one of my editors here at NEJM Journal Watch, Kristin Kelley, expressed astonishment that I wasn’t promoting my own writing on Twitter. “Every writer does this,” she said, bluntly. Then she gave me a brief tutorial.

Now I do it regularly. Example:

Mask and vaccine mandates? Check. Socializing and networking over meals and drinks? Check. Some thoughts about this uncomfortable paradox here.

Big In-Person Medical Meetings and Cognitive Dissonance for ID Docs https://t.co/TnIz1Kgq2G @PriyaNori— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 17, 2022

Third, after dipping my toes in the water, I started seeing the highlights of major scientific conferences on Twitter without having to travel. No time away from home. No airfare. No registration fee. No hotel charges. For example, the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, or ECCMID, is a terrific meeting I’ve “attended” every year via Twitter since 2016.

Believe me — I am well aware that Twitter can be a place of discord and clashes, a site where people say stupid things they later regret, things that literally ruin their careers. Worse, Twitter can be the source of serious bullying and threats. Having been the target of some of these attacks (which most reliably occur after I post something about the benefits of vaccines), I can only imagine what it’s like to be the target of something broader, or even more sinister.

How then, to stay out of trouble? Here I turn repeatedly to Peter Sagal, best known as host of NPR’s eternally funny “news” show, Wait Wait, Don’t Tell Me. Peter’s “Rules of Twitter” are so effective that not only will adherence to them generally keep you from entering into the toxic fray, but you’ll find yourself applying them to real life too, making you a happier person. That’s pretty great.

So here they are in their entirety, conveniently “pinned” to the top of his profile page:

These are my Rules of Twitter, developed over many years via trial and (mostly) error. They are *my* rules, related to what I want to do On Here and what I want to avoid. Yours may and will differ, but I do suggest figuring out what they are. pic.twitter.com/tib7vZ4ORF

— @petersagal.bsky.social (@petersagal) November 8, 2021

For this year’s IDWeek, I was kindly invited to present the good side of #IDTwitter. The session also included two terrific talks by ID colleagues — Dr. Krutika Kappalli, who discussed what it feels like to be the victim of hate speech and abuse triggered by speaking plainly about science and public health, and Dr. Payal Patel, on how to engage news media from across the political spectrum on ID issues.

People who attended IDWeek can see watch the talks, but for others, I’ve gone ahead and posted a condensed version in a Twitter “thread” — check it out! — then come back here and watch this truly hysterical video.

Which I learned about on Twitter by “following” several talented comedians, including this guy.

November 21st, 2022

Five ID Things to Be Grateful For, 2022 Edition

Household magazine, 1952.

In what’s something of a holiday tradition on this site, I hereby present 5 ID things we can be grateful for as we prepare for the best holiday of the year. Why the best?

Family and friends. A nice big meal, with something for everyone. (My family of four has two vegetarians — they have plenty to eat.) No pressure about gifts.

And, most importantly, a chance to express gratitude, something we all should do more often.

I say you can’t beat it, and since this is still my column/blog/whatever (checks over his shoulder), that will be the final decision.

Onto the 5 things, starting with the very most obvious:

1. Trending toward endemicity. No, the pandemic isn’t “over” — especially for people who are immunocompromised, or very medically fragile. And Long Covid remains a persistent challenge and mystery.

But boy has COVID-19 changed.

I speak annually each fall in a Harvard postgraduate course for hospitalists. This is the third year I’ve spoken about management of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients.

The first 2 years, my case-based talk included patients with oxygen-requiring pneumonitis, with discussions about remdesivir, dexamethasone, tocilizumab, baracitinib, and other promising immune-based therapies. Pulmonologists spoke of ventilation strategies and ECMO.

This year? My case for discussion was someone admitted to the hospital with congestive heart failure, “incidentally” found on testing to have COVID-19 — maybe it tipped them over, maybe not. Most of the talk was about outpatient therapies (yes, it’s a hospitalist course — it was a reach), and managing that tricky nirmatrelvir rebound syndrome.

“We might have you pivot back to HIV,” said the course director, inviting me back for next year’s course. That would be just fine!

So while there’s still plenty of COVID-19 out there — and influenza and RSV have come charging back — we appear to be past the stage where our ICUs fill up with COVID-19 pneumonia, forcing our hospitals to restrict their basic functions. Draconian family visitor policies are gone. Some hospitals have even stopped testing all their asymptomatic inpatients.

Fingers crossed it stays this way. After all, it was last year at this time that Omicron hit. I’ve learned, with this virus, not to take anything for granted.

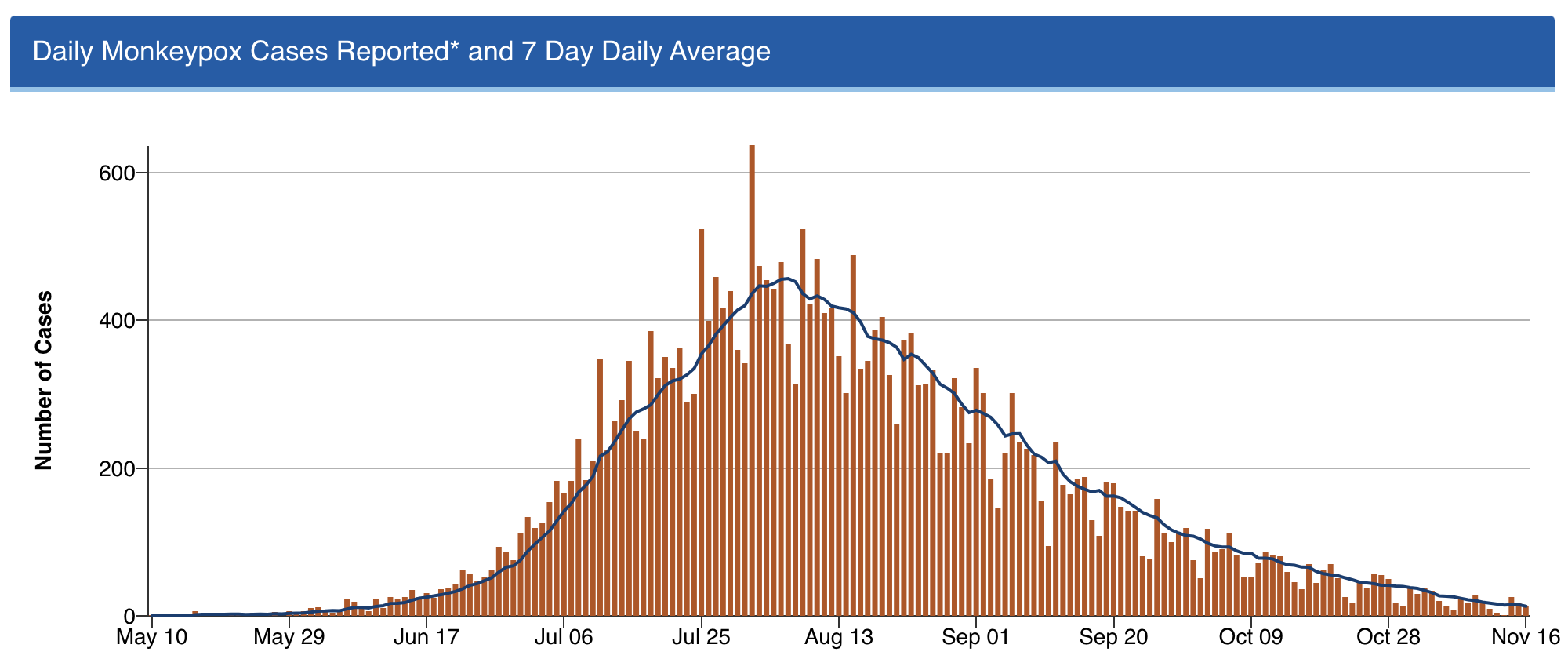

2. Monkeypox is under control. Back in July, one of my colleagues was spending nearly all of her time managing referrals for confirmed and suspected cases of this new (at least to us) sexually transmitted infection.

(And yes, it’s mostly sexually transmitted. I know there are debates about this nomenclature, but that’s for another time.)

It was tough, and her actions were heroic — full PPE for each case. Tecovirimat applications to the CDC. Struggling with Jynneos vaccine shortages. And, worst of all, some cases so severe they required hospitalization.

As the case numbers increased, we had to wonder — when was the steep increase in case numbers going to peak? Anecdotal cases with no apparent exposure, outside of the primary risk group (men who have sex with men), raised the possibility that this scary thing would explode even further.

But thanks to a spectacular collaborative effort by CDC, local public health officials, the gay community, and the roll-out of the Jynneos vaccine, the incidence of this viral infection dropped wonderfully.

Got to love this curve:

Shout out to Dr. Demetre Daskalakis (among others) — but I’ll give him extra credit as he’s a graduate of our ID program. He was quite the special ID fellow, and is quite the special ID doc!

3. Professional meetings are back — but now with a remote option, too. I spoke recently with someone who attended IDWeek this fall in Washington DC, asking her what she thought about the experience.

“It was wonderful,” she said. “I had a great time.”

She smiled as she said this — almost guiltily, I thought.

It’s an opinion I’ve heard repeatedly from those who went. There was something so strange, yet so exhilarating, about attending. Seeing old friends and colleagues for the first time in years. Marveling at the survival of our specialty, brutal though our experience has been. Sharing what it took to get through it.

But not everyone is ready to go back to these meetings — I understand that. The cost, the carbon footprint, the time away from work and from family — all negatives. And let’s be ID nerds about it, there’s no doubt that interacting with others at professional meetings is a risk factor for transmission of viral respiratory tract infections. Always has been, always will be.

Fortunately, the big meetings seem to understand all this, and now offer the chance to attend remotely. For IDWeek, 7431 attended in person, 2160 virtually.

I would call that progress.

4. Dolutegravir — and by extension, bictegravir — hold up stronger than ever. For those readers who don’t do HIV treatment, here’s little secret — it’s never been easier. Dolutegravir- and bictegravir-based treatment, consisting of these drugs plus tenofovir/emtricitabine (or lamivudine), is so sensationally effective that all but the tiniest fraction of people who take this combination achieve virologic suppression.

(I lump dolutegravir and bictegravir together since they’re quite similar — enough so that there’s even a colossal legal agreement about it.)

It’s worth acknowledging up front that these treatments aren’t perfect. We still have that frustrating weight gain issue, and a signal of possible excess cardiovascular risk. A fraction of people get headaches and insomnia from the drugs, and can’t take them. But by and large these treatments just work — and work better than anything we’ve ever had in the 35 years we’ve had antiretroviral therapy.

Treatment-naive and treatment-experienced. Resistance to the NRTIs or no resistance. Viremic or suppressed. Young and old. Advanced HIV disease or asymptomatic.

Sure, there are exceptions. If you push any drug too hard, with suboptimal adherence, or super high viral loads and severe immunosuppression, or drug interactions, you can select for resistance. In the NADIA trial of people failing second-line therapy, dolutegravir plus 2 NRTIs was noninferior to darunavir/ritonavir plus 2 NRTIs, but 9/235 in the dolutegravir strategy developed resistance, versus zero in the darunavir arm. The world is now conducting a massive conversion of most HIV treatment to “TLD” (tenofovir-lamivudine-dolutegravir), and it will be critical to follow this roll-out to explore the incidence of this resistance, the risk factors, and the optimal management.

But so far, in clinical practice, resistance to these second-generation integrase inhibitors is a rare enough thing that most experienced HIV clinicians have at most a handful of such cases in their practice. And we essentially never see it when people with virologic suppression switch.

Oh, and by the way — that concern about dolutegravir exposure during conception and neural tube defects? Gone! Thanks to the primary investigators, who accumulated a ton of more data since the first report in 2018, the incidence is now comparable to that with other ART strategies. Dolutegravir is now a recommended treatment for all pregnancy categories.

That last fact alone is worth some serious gratitude.

5. #IDTwitter — still a wonderful and entertaining place to learn.

Yep, chaos at the top notwithstanding, it still is.

But that’s the topic for my next post … provided the site is still running when I write it!

Hey, if you ignore the #EndOfTwitter stuff, the content on here remains pretty great https://t.co/O73xiLS6ZI

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) November 18, 2022

Happy Thanksgiving, Everyone! What are you grateful for this year?

November 7th, 2022

Five Quick Questions from Our Course, “ID in Primary Care”

Examples of non-digital, non-electronic learning tools, for historical purposes only.

As noted on this site before, we put on a course called “ID in Primary Care” every year for clinicians doing truly the hardest job in medicine — frontline primary care. Why is their work so challenging? While we can focus on one field, infectious diseases, they have to be aware of everything.

Tough task indeed.

We’ve been holding our course virtually since 2020, so this is our third time with the online-only, live-streaming format. On the plus side, this has allowed a greater number of participants, saves a whole lot of money both for travel and the meeting venue, and certainly has a much smaller carbon footprint.

On the other hand, we miss the direct contact with those who attend. Plus, Zoom fatigue is a real thing, and we have zero idea if our jokes land.

Pros and cons of this approach aside, we still draw a great mix of internists, family practitioners, nurses, and PAs, and every year they ask us terrific questions about clinical problems that they encounter on a regular basis.

Here are a quick five:

Question #1: I have a patient who says they get recurrent shingles several times a year, so she’s periodically back on valacyclovir. I can’t find anywhere how to manage this — boost their vaccine? Suppressive valacyclovir? If so, what dose? Help!

Answer: Ah, the patient with “recurrent zoster” — I put it in quotes because most of the time it’s actually not zoster at all. It’s either HSV (which can look strikingly similar) or a dermatologic manifestation of post-herpetic neuralgia, where someone has pruritus or discomfort in the same anatomic location of a zoster outbreak, so they scratch away and develop itchy red bumps.

When patients do get another case of zoster, it’s usually in a different dermatome, separated from the first episode by several years.

Have your patient stop the chronic antivirals if they’re on them, and next time they have an outbreak, get a swab and do a PCR for HSV and VZV on the lesions. If the diagnosis is still uncertain, have them check in with your favorite ID-oriented dermatologist if you’re lucky enough to work with one of these brilliant clinicians.

For more on this entity, read The Patient with “Recurrent Zoster”, which I have sent along to numerous eConsulters over the years.

Question #2: My patient is about to start a TNF blocker for ulcerative colitis. She comes from a country that gives BCG vaccine to all children. Should she get both an IGRA and a tuberculin skin test to rule out latent TB? I worry about false positives with the BCG.

Answer: If your prior probability of latent TB is low, as it is for most U.S. citizens, then one test should suffice, and go with the interferon gamma release assay (IGRA). However, if the person is from a highly TB-endemic region, especially if they recently immigrated here, and are about to start these immunosuppressive medications that greatly amplify the risk of TB reactivation, then the guidelines say to consider doing both — and this is what we would recommend. If either test is positive, I would give preventive therapy before starting the anti-TNF agent.

And no, prior BCG should not dissuade you from this strategy. As some regions where this vaccine is administered have very high rates of TB, there is no way to distinguish positive skin tests from BCG (which fade over time), versus from latent TB, versus both — and the vaccine doesn’t work that well in adults anyway.

For more, check out these terrific online resources:

BCG and false-positive tuberculin skin tests

Question #3: My patient has recurrent UTIs, but she is older with chronic renal disease. What’s the real story on use of nitrofurantoin in this setting?

Answer: Nitrofurantoin has made an amazing comeback in UTI treatment over the years, largely due to rising rates of community resistance to other agents and concerns about fluoroquinolone toxicity. However, it has poor tissue penetration, and prescribing information has long said not to use at CrCl <60 ml/min because of insufficient renal excretion and accumulation of the drug leading to more toxicity — in particular that nasty pulmonary hypersensitivity syndrome.

By contrast, in a 2015 review by the American Geriatrics Society, the conclusion was that nitrofurantoin could be safely used down to an estimated GFR of 30, provided the treatment course was 7 days or shorter.

Helpful to know this if other options are limited.

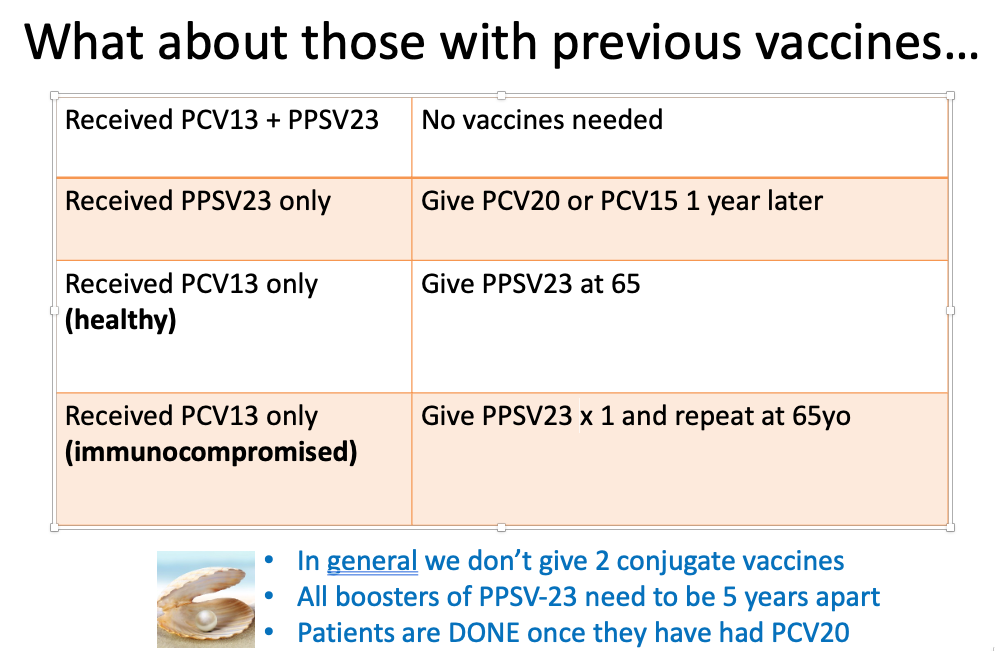

Question #4: I know that the pneumococcal vaccine recommendations have been updated, but it’s so confusing what to do with so many options. Any simple way of addressing this, in particular for those patients who’ve been vaccinated before?

Answer: We’re most definitely in a transition phase when it comes to pneumococcal vaccination, driven by the availability of the two new conjugate vaccines, especially the 20-valent one. Sometime in the near future, everyone getting a pneumococcal vaccine will get the pneumococcal 20-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV-20), and be done. Hooray!

But until then, we have a whole slew of people who’ve received older vaccines, both the conjugate (PCV13) and the polysaccharide versions (PPSV23). What should we do with them now?

My colleague Dr. Mary Montgomery put together this handy slide for her talk on adult immunizations, which I am sharing with her permission:

Question #5: Is the pandemic over?

Well it’s not over — but it sure has changed.

Want evidence? Just imagine this video appearing a year ago — inconceivable.

Today? It was a big hit on SNL this past weekend.

Suspect that for some, it’s too soon, while for others, it’s perfectly timed satire.

For me, it’s both. How about you?

October 25th, 2022

Yes, Even ID Doctors Get COVID — Including Famous Ones

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, various public figures have contracted the disease.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, various public figures have contracted the disease.

Tom Hanks, way back in early March 2020, was arguably the first globally famous person in the world to test positive for the virus. The announcement came right as much of the world prepared to shut down. My friends and I were wrapping up what would be our last indoor poker game for over a year when the news broke.

“Tom Hanks and wife test positive for corona,” said my friend Scott, looking at his phone between hands. We all reflexively reached for the hand sanitizer I’d strategically placed beside each person’s chair. Hey, back then it was fomites — remember?

Hanks made the news public in a typically generous and optimistic way. He’s the nicest super-famous-rich person on the planet, isn’t he? And his COVID episode elicited sympathy, and hope for a quick recovery, for both him and his wife.

But he’s a beloved actor, and hardly the kind of person to bring out the meanies.

Because since then, in lockstep with a virus that has infected a massive proportion of the world’s population, we’ve had a veritable cavalcade of famous people come down with COVID.

Let’s see, off the top of my head — two presidents, one vice president, prime ministers, numerous other politicians, multiple actors, several radio and TV talk show hosts, athletes, rock stars. You name it.

Plus, Tony Fauci.

And now, my friend and former colleague, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky. The announcement came just as we were finishing our first in-person meeting, IDWeek — which, as I predicted, was filled with unmasked work-related and social gatherings in conference rooms, hotel lobbies, and restaurants.

“This Marriott must have some special anti-infective power,” said one of my colleagues. “Seems when you leave the convention center and enter the lobby, you no longer need a mask.”

So why bring up the CDC director’s case of COVID? Because it has elicited one of my least favorite aspects of the pandemic since it started — the tendency for some people to gloat about another person’s illness, criticize that person, and to use it as a way of endorsing their particular stance on the disease.

Look, I made no secret about my opinion on how our former president handled the pandemic in the spring of 2020. But when he came down with COVID in the fall of that year, in the pre-vaccine era, and got pretty darn sick, I never wrote, or even said Good — he deserves it. Same goes for the parade of COVID-denialist radio talk show hosts, whose deaths struck me as both pathetic and tragic.

Frankly, it pained me to hear some friends and colleagues take this stance, and I shared my views with them at the time. You’re reveling in the illness and misery of others? Doesn’t that make you feel yucky?

Same happened with Dr. Fauci, and now Dr. Walensky — the negative reactions come from all around. Anti-vaxxers and libertarians on one side, COVID-zero and public health zealots on the other. Implication? You’re responsible for the mess we’re in; now this is your just desserts.

It’s painful to see and makes me so uncomfortable. Because the reality is that we’re all struggling to do our best with this tricky virus, which was only discovered in early 2020 — and hence leaves us reading a very new, and sometimes non-existent, playbook. There is no person whose call on policies or predictions could be 100% right, 100% of the time. Doesn’t matter how smart or famous you are.

So here’s a bold idea — how about we treat every person’s illness with the kindness and compassion we’d want when our friends, our family members, and we ourselves get sick?

It’s really not so hard to do, is it? After all, we did it with Tom Hanks.

October 17th, 2022

Big In-Person Medical Meetings and Cognitive Dissonance for ID Docs

Dissonance: lack of agreement; inconsistency between the beliefs one holds or between one’s actions and one’s beliefs; a mingling of sounds that strike the ear harshly.

Dissonance: lack of agreement; inconsistency between the beliefs one holds or between one’s actions and one’s beliefs; a mingling of sounds that strike the ear harshly.

It started shortly after the chaotic, disruptive, and all together unpleasant Omicron wave of 2021–22.

It continued through the BA.2 and BA.5 surges, and now plays on through the swarm of Omicron variants that float all around us.

It’s the persistent background sound of an ominous minor chord signaling COVID cases to those of us who specialize in Infectious Diseases — never going away, waxing and waning in volume, all summer long and now into the fall.

That’s one of the two chords playing repeatedly and giving us information about test positivity rates, wastewater data, vaccine and treatment-evasive variants, and generating calls from patients, colleagues, friends, and family members about having COVID.

Undoubtedly this chord will be playing louder as winter arrives, along with variants BF.7, BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, and who knows what else is in store. Respiratory viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, are seasonal, after all.

Playing at the same time is a different chord, in a happy major key — probably C major, no less. People hearing this chord can all but ignore that there’s plenty of COVID out there. Sniffles again are allergies, sore throats and coughs no more ominous than what they were before the pandemic. Meaning, not very.

COVID test for that mild sore throat? You’ve got to be kidding. Mask up for crowded indoor spaces? C’mon, that’s so last year.

Schools, restaurants, bars, concerts, big weddings, places of worship, gyms, travel — as noted here previously, all back to normal.

Most people don’t experience these two chords, playing simultaneously. But we do, we ID doctors — a scary chord in one ear, a happy one in the other.

Where does that leave us ID doctors? With a whole lot of dissonance — the sound of those two chords, major and minor, playing together. Minor if we’re caring for the immunocompromised and/or older and frail, or leading the infection control team at the hospital, or managing tight clinical schedules with people dropping out for 7–10 days for COVID, or responding to queries about COVID — the volume of which correlates perfectly with local wastewater concentrations of SARS-CoV-2.

But it’s a major chord if we’re trying to be like most “regular” people, just wanting to get back to a pre-pandemic life.

It’s an appropriate time to bring up this conflict, because we’re on the eve of our big professional meeting, IDWeek — first in-person IDWeek since 2019, which was, of course, the Before Times.

You won’t be surprised that this meeting of ID specialists has strict masking policies, and a vaccine requirement to attend.

You also won’t be surprised to hear that, like the rest of our species, ID docs can’t socialize if it involves eating and drinking without taking off our masks. Figure that half the motivation to attend these meetings (at least) is for this kind of networking. Or that many of us, in our non-ID time, have gone to weddings, parties, gyms, restaurants, concerts …

Some might call this hypocrisy. The very definition of two-faced — yes, literally! Masked while indoors at the meeting, unmasked while sharing lunches, drinks and dinners with colleagues we haven’t seen in ages. Hey, what’s it going to be, ID docs?

Others could argue it’s still rational to require masking at the meeting. As Dr. Priya Nori noted to me during a recent discussion on this topic, we’ll be reducing our risk of viral respiratory infections at least half the day — and some risk mitigation is better than none. This was my view when I shared being invited to a group work meeting that, to my chagrin, appeared to take place in a crowded basement closet. Couldn’t we do better on ventilation than that?

There’s validity to both of these views (hypocrisy vs. risk mitigation), though certainly Dr Nori’s is the kinder and more generous one.

But I have another interpretation. I think we’re just confused. And nervous. And tired. And humbled. And, speaking for myself, we’re collectively suffering through a bit of PTSD, recalling the last two really awful winters, and for those of us from certain urban centers, the nightmarish March–April of 2020.

We can certainly hope those days are behind us, that our vaccine and infection-induced immunity continues to attenuate the severity of disease, that our ICUs and ECMO machines will remain unstressed, our elective surgeries not postponed.

But we don’t know that. Hence the dissonance.

And I hear it, and suspect everyone attending IDWeek in Washington DC this week will hear it too.

October 10th, 2022

Molnupiravir Results in PANORAMIC Study — It’s Not All Bad News

Last week, the large PANORAMIC trial of COVID-19 treatment in outpatients with mild-moderate disease appeared in a pre-print. This large (25,783 participants!) randomized, open-label study compared molnupiravir vs. usual care in adults 50 or older, or having comorbidities known to make severe disease more likely.

The results?

Molnupiravir vs standard of care for outpts with Covid19. No difference in the already low rate of hosp/death, but take a look at this Time to Recovery 2ndary endpoint, a 4-day benefit! Robust across subgroups. Caveat: Open label design. https://t.co/t07aqg68s9 h/t @ASPphysician pic.twitter.com/MExXZLOTp2

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 6, 2022

Four days faster recovery with treatment! You might think this would be welcome news.

Ah, but think again. Because the response from the ID cognoscenti was lukewarm, and that’s putting it kindly.

Many cited the study’s open-label design as a major limitation, negating the favorable time-to-recovery result. The placebo effect is certainly in play when a person knows they are receiving active treatment.

Some noted the ongoing concerns with molnupiravir and mutagenicity — and the theoretical worries about generating variants.

Others criticized the cost of the drug.

But the major theme of the naysayers emphasized the inability of the treatment to demonstrate a benefit in the primary endpoint of interest — hospitalization or death. Here the result was quite low for both arms, and equal, at 0.8%. Not a bit of difference, and this lack of efficacy is also what the headlines typically featured.

As a result, when I polled people on whether they would prescribe molnupiravir now that they know the results, it didn’t surprise me that a majority said no.

Molnupiravir vs usual care in large open-label randomized trial. Pts mostly vaccinated; omicron era:

– Primary endpoint: no difference in hosp/death (0.8% for both)

– 4.2 days faster reported recovery

– faster viral clearance

– serious AEs 0.4% for both

Would you prescribe it?— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 8, 2022

With the caveats that this sort of poll is only representative of the people who saw and answered it, and that Twitter can be a really negative place — like “staying too late at a bad party full of people who hate you” — I do think it’s worth acknowledging these important concerns about both the study and the drug.

But it’s also worth highlighting the good news coming out of this trial — and it’s very good news indeed.

First and foremost, the amazingly low incidence of hospitalization or death underscores how much less severe COVID is now compared to when it first hit the human race. It’s especially notable since the study population included only those at risk for bad outcomes. When it comes to most infections, it’s a wonderful thing not to be immunologically naive, and the participants had very  high rates of vaccination and/or prior infection.

high rates of vaccination and/or prior infection.

(Parenthetically, the lower disease severity presents a virtually insurmountable challenge to conducting a clinical trial with this “hospitalization or death” endpoint — as noted by Dr. David Boulware, the sample size would need to be extraordinarily large.)

Second, let’s go back to the observed faster time to recovery for a moment. A 4.2-day improvement in time to recovery with no major short-term side effects — or drug interactions — is nothing to sneeze at, if you’ll forgive the very apt cliche. As a point of reference, this is quite a bit more than the observed clinical benefit seen with oseltamivir and baloxavir for influenza, which is typically 1-2 days. Note also that there is no mention of clinical or virologic rebounds, though perhaps the researchers did not assess for these endpoints.

So let’s imagine you are a person with COVID. You’re miserable — feverish, sneezing, coughing, out of work. Not hospitalization-level sick, but feeling pretty lousy.

Your doctor tells you they have a 5-day treatment that, in a large study, shortened the time to recovery by 4-5 days compared to people who didn’t get the treatment.

Plus, there were no major side effects, and the amount of virus dropped faster, too.

Wouldn’t you at least consider it?

Or, as Dr. Sarah Scott writes:

Well said. While acknowledging that the open-label design makes ascribing this benefit solely to the drug is impossible — people really want to believe that their treatment is making them better — we can also note that this difference in time to recovery is substantial, even by the standards of other non-placebo controlled trials.

Finally, the PANORAMIC investigators deserve a ton of credit carrying off this very large, pragmatic clinical trial. We all look forward to seeing it go through peer review and revision, information about rebounds (if they happened), as well as the promised follow-up data regarding long COVID. Also, the results of the nirmatrelvir/r (Paxlovid) arm of the study promise to be particularly interesting, as this is way more widely used than molnupiravir for COVID treatment, at least here in the United States.

Meanwhile, enjoy this video, because I certainly did.

September 28th, 2022

Even if You Think “The Pandemic Is Over” — Let’s Make In-Person Meetings Safer

“The pandemic is over.”

“The pandemic is over.”

Someone very famous used these words recently, triggering all kinds of controversy.

While most ID clinicians groaned at the comment, knowing that it would be taken out of context, repeated in headlines without any of the President’s cautionary statements, and fuel COVID denialists, it’s also worth acknowledging that most of the country really does feel this way.

Look, if at least 90% (rough estimate) of travelers at Boston’s Logan Airport no longer wear masks, either while waiting for their flight or on the plane, it must be 99% in most other U.S. airports.

(I checked with my colleagues in other cities. It is.)

Plus, schools are open, restaurants busy, concerts and sporting events full. Postponed weddings are happening. People again travel for business and academic meetings.

If we haven’t returned to prepandemic “normal,” whatever that is, we’re certainly heading that way. Why? Because you’d have to be a hermit if you either haven’t had COVID yourself, or don’t have several close family members or friends who’ve had it — sometimes multiple times — and recovered uneventfully.

“The flu I had a few years ago was much worse,” said one of my own friends this week, walking his dog in our neighborhood, and looking just fine.

In short, the infection remains incredibly common, likely will get most if not all of us eventually, and — here’s the fact — just isn’t as severe as it once was, mostly because of vaccines and prior infection-induced immunity. All these things are true.

This is the part of the post where I need to insert these critical and essential caveats. Some people still get quite sick from COVID — I worry in particular about those with weakened immune systems. Some people will get long COVID. And testing positive is still enormously disruptive, forcing people into isolation and wreaking havoc on schools, workplaces, daycare centers, and many carefully planned events. In short, COVID still s–ks.

You can quote me on that. Colds, flu, RSV, and company are pretty lousy too.

But as part of the improvement in the prognosis for COVID, and the opening of our society (even for ID docs) to multiple activities that previously had been cancelled, I want to address one in particular — and that’s in-person meetings.

We can’t make them 100% safe. Can we at least make them safer?

So far I’ve traveled to three, and of course my colleagues have started doing the same. IDWeek is coming up in October, CROI in February, and these meetings will undoubtedly include many meetings and unmasked social interactions that could spread both COVID and other respiratory viruses. I get that.

But mitigating strategies are still welcome. One such meeting at IDWeek specifically cited that it would take place in a room “that has accordion doors so it can be opened up for airflow, as well as a wrap-around balcony.” Terrific. Ventilation is good — it’s one of the major lessons learned during the pandemic.

Another meeting asked us to do rapid antigen tests on arrival. No, these tests aren’t perfect, and they don’t screen for other respiratory viruses, but the positive predictive value of them is high. I’d welcome a cluster randomized trial of testing vs. no testing prior to in-person meetings.

So let me share an example of what not to do, “pandemic is over” notwithstanding.

I recently went to a meeting of other ID specialists, and planned ahead of time to be unmasked during both the meeting and the lunch. I figured we ID docs would not attend if we had a respiratory illness. We’ve gotten good at that, avoiding illness “presenteeism,” and most people with contagious respiratory viruses have symptoms. So that was some reassurance.

But here’s the not-OK part: The meeting took place in a tiny, crowded, low-ceilinged room, with barely a few inches between seated participants — the very converse of “social distancing.” If someone had one of those CO2 meters placed strategically in the center, I suspect it would have been sounding its alarm from the first 30 minutes.

The room was small enough that multiple people commented about the forced intimacy, making jokes about how ironic it was that we ID doctors would be sharing so much mutual air over the next several hours — especially because it was a beautiful fall day. “We should have the meeting outside,” said one of the organizers. Ha ha.

Yep, it was packed in there — if not quite phone booth stuffing or Marx Brothers-stateroom tight, certainly much more crowded than any meeting room I’d been in for years. Let’s just say it’s a good thing we all showered after our morning run or time on the elliptical, because any hygiene infractions would have been immediately evident. Lunch, fortunately, was in a much larger, well-ventilated room.

So I wore an N95 mask during the meeting. I was the only one.

Because COVID still s–ks.

https://youtu.be/NWFl2S5-Ua0

September 8th, 2022

A Back To Work ID Link-o-Rama

Zelda, Zoe, and Louie on the cover of their latest album, Parallel Paws. With apologies to Debbie Harry and Chris Stein.

A few nuggets are rattling around in the inbox post Labor Day, including this extraordinary photo of our family dogs Zelda, Zoe, and Louie, posing for their latest album cover.

Woof!

Besides, I haven’t done one of these Link-o-Ramas since January 11, 2021! That was either 20 months ago or 20 years, hard to keep track of time these days.

Enough with the introduction. On with the links — starting with some highlights from this year’s 2022 AIDS Conference in Montreal:

- Should people on PrEP or with HIV with a recent history of bacterial STIs take doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis after sex? The cleverly named doxyPEP study showed a marked reduction in all bacterial STIs, including gonorrhea — a benefit not observed in a similar study conducted in France. And living in New England, I am, of course, reminded of post-tick bite doxycycline every time I hear about this strategy!

- Treatment of people with HIV/hepatitis B co-infection with BIC/FTC/TAF led to more favorable hepatitis B outcomes at 48 weeks than TDF/FTC plus DTG. These results suggest that TAF should be preferred over TDF for coinfection treatment. FYI, these were two of the three potentially practice-changing studies presented at this year’s 2022 AIDS Conference. (The third study, using injectable cabotegravir-rilpivirine in PWH with viremia, I’ve covered in more detail previously.)

- Another person with HIV has been cured with a stem cell transplant from a CCR5-negative donor. While this “City of Hope” patient with AML is just the fourth (or fifth, if you count the mystery Dusseldorf patient) to be cured, each cure case adds to our understanding of how we might accomplish this one day with more practical methods.

- This example of “exceptional” HIV control may give us an alternative to a sterilizing cure of HIV. Diagnosed with acute HIV in the 2000s, with a baseline HIV RNA of 70,000 and CD4 of 800, she was treated with ART and a grab-bag of immune based therapies (cyclosporine, IL-2, interferon, GM-CSF). Now off ART for more than 15 years with stable CD4s and an undetectable HIV RNA, she has a steady decline in the HIV reservoir with “enrichment of memory-like NK cells and CD8+ gamma delta T cells with NKG2C.” Sure. As always with such isolated cases, how much can we attribute to our interventions, and how much to a one-off very fortunate immune response?

- Targeted versus “shotgun” metagenomic sequencing on sonicate fluids derived from patients with suspected prosthetic joint infection had comparable yields, with the former being less expensive and having a faster turnaround time. Note that it detected potential pathogens in 48% of culture-negative PJIs. How long before such molecular testing becomes standard of care?

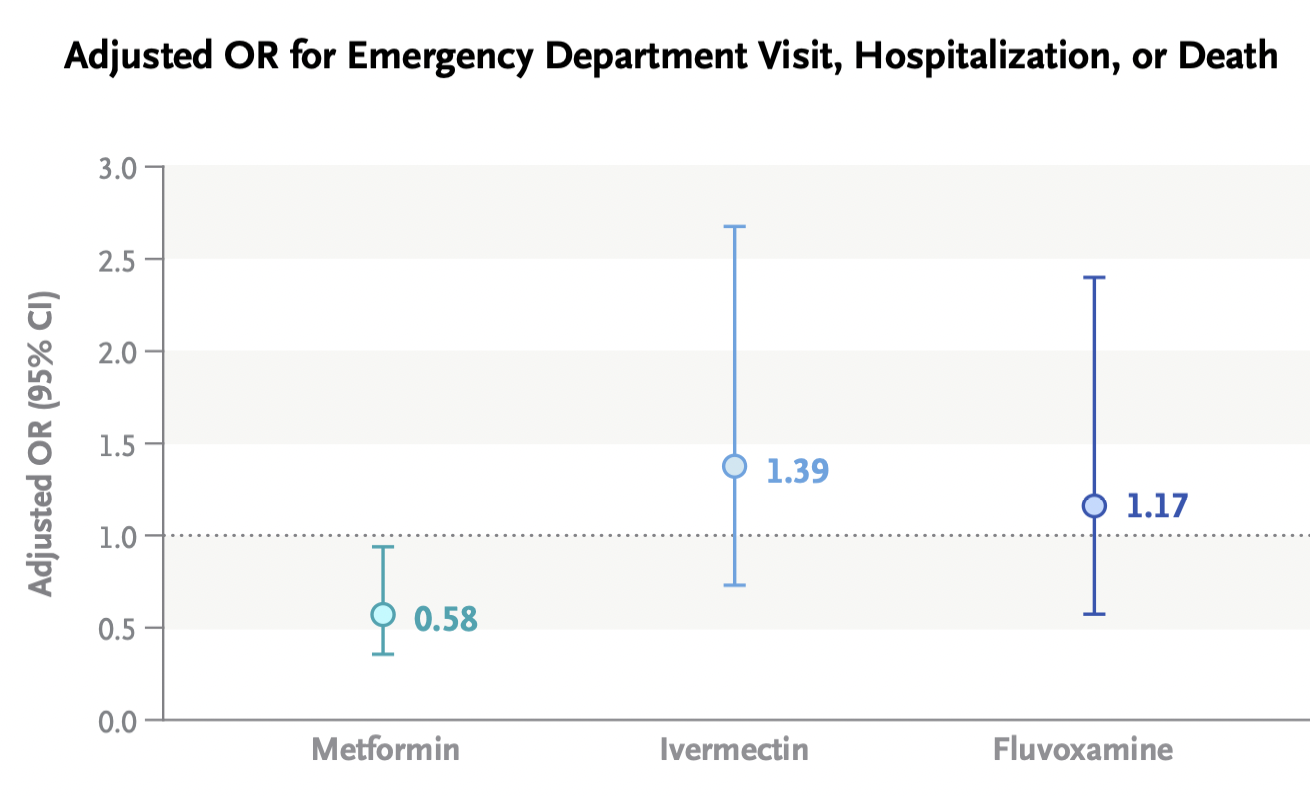

- A randomized clinical trial comparing ivermectin, fluvoxamine, and metformin to placebo for outpatients with COVID-19 found no significant difference in the primary outcome compared to placebo. One can be encouraged, however, by this signal from the metformin arm by looking at the secondary outcome of emergency department visit, hospitalization, or death. For a detailed further discussion of this interesting study by Dr. David Boulware, a co-investigator, read here. Note that a higher dose fluvoxamine strategy (which worked in the TOGETHER trial) is part of the ongoing ACTIV-6 clinical trial.

- Metformin shows up in numerous ID-related studies. In addition to its pleiotropic endocrine and anti-inflammatory effects, we can add antiviral activity against KSHV, SARS-CoV-2, Zika, and dengue, and a potential adjunctive role in tuberculosis, among others. And if you want to go further down this metformin rabbit hole, it’s not just being looked at for infection!

- A systematic review suggests that doxycycline for community-acquired pneumonia could make its way into the next guidelines. Resistance to azithromycin and the toxicity of fluoroquinolones make this a highly desirable option. Great accompanying editorial by the legendary Dr. Daniel Musher.

- Do either vaccination or prior infection reduce a person’s infectiousness when they contract COVID-19? Once we get past the fact that neither eliminates the risk of transmission — nothing is 100%! — we can at least cite several studies that prior immunity to SARS-CoV-2 reduces transmission risk, including this recent one done in a prison setting. Such data may point to a more stable time without marked surges, as community-wide immunity from either vaccine or infection or both could flatten rapid spikes in transmission.

- China has approved an inhaled vaccine for COVID-19. Used as a booster strategy after prior vaccination, the adenovirus-based vaccine induced humoral, cellular, and mucosal immunity. It’s the mucosal immunity that we hope will be more effective in blocking infection than our current vaccines. This is a big challenge, so it’s fortunate that many — around 100! — inhaled vaccines are under investigation.

- Are we treating peripartum infections appropriately? This review appropriately challenges the 2017 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines, which remarkably (and weirdly) still recommend ampicillin (or clindamycin) plus gentamicin — despite the fact that resistance to ampicillin is common, the dosing of these two drugs is complex, aminoglycosides penetrate poorly into abscesses, and the longtime availability of several safer and likely more effective options — such as piperacillin-tazobactam. “Get with the times” indeed!

- Treatment of cerebral toxoplasmosis with TMP/SMX appears to be as effective and less toxic than pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine. It’s also way less expensive, and much easier to take. This excellent systematic review could (some would say “should”) be guidelines-changing, as there is unlikely to be another prospective clinical trial conducted anytime soon, and most of the world already has made the switch.

- People who inject drugs admitted with complicated S. aureus bloodstream infections (including endocarditis) should be offered oral antibiotics at the time of discharge if they can’t safely continue intravenous therapy. Outcomes are significantly better than no antibiotics and comparable to IV after 10 days of IV treatment. Some would say switching to oral therapy should be the default option already — for everyone, if possible.

- In pregnant women, dolutegravir-based ART was superior to atazanavir–ritonavir, raltegravir, or elvitegravir–cobicistat in achieving viral suppression at delivery. It was similar to darunavir- and rilpivirine-based regimens, but the former is suboptimal due to twice-daily dosing, the latter because of food requirements and contraindicated acid-reducing therapies. With dolutegravir as the preferred option right now, we urgently need similar observational data on bictegravir/FTC/TAF, which is extensively used in clinical practice.

- Should linezolid replace clindamycin as adjunctive therapy for severe group A strep necrotizing fasciitis and toxic strep syndrome? Rates of resistance to clindamycin among beta strep species are high, and linezolid has similar in vitro suppression of toxin production. Makes sense. But file this one under the long list of questions for which there will never be a randomized clinical trial.

- SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen was detected in a majority of patients with long-COVID, or PASC. In 12 who had longitudinal samples, detection lasted 2-12 months. These results, if confirmed, imply a persistent reservoir of active viral replication, viral antigens, or both — and could lead to diagnostic tests and treatments, both of which are now sorely lacking.

- A clinical trial in the United Kingdom is testing tecovirimat treatment for monkeypox infection. Conducted remotely, with any clinician eligible to refer participants, the PLATINUM study tests tecovirimat 600mg twice daily for 14 days versus placebo on the rate of recovery and time to viral clearance assessed by weekly self-taken swabs. A similar study in the USA, run by the ACTG and called STOP, is expected to start soon.

Non-ID section:

- Even non-tennis fans might like this 2012 story about Frances Tiafoe. Written when he was just 14, the piece describes the childhood of the now 24-year-old Tiafoe, the first American man to make US Open semifinals since 2006. Stories like this definitely make me feel more patriotic than any shallow flag-waving! Tiafoe will certainly have his hands full tomorrow when he faces tennis wunderkind Carlos Alcaraz!

- A cardiac surgeon continued to operate despite a record number of malpractice suits, bad patient outcomes, and concerns raised by colleagues. At the very core of this terrifying story — as with many similar examples — is the strong financial incentive for hospitals to hold on to their “superstar” surgeons given the high revenues they bring in. Awful awful awful.

- Here’s a great depiction of participant behavior at scientific meetings. Well done, Dr. Ilan Schwartz!

Extroverts and introverts at conferences https://t.co/c6lm45DjKv

— Ilan Schwartz MD PhD (@GermHunterMD) September 7, 2022

Seems particularly appropriate for us ID doctors, as we gradually return to in-person big public meetings.

- The rock group Blondie released a deluxe box set celebrating the years 1974-1982. In case you’re wondering about the inspiration for the photo at the top of this post, this classic album was released 44 years ago this month, became a prominent part of the soundtrack of my college years … and it wasn’t called Parallel Paws!

Anyway… the earworms all day have been Blondie so I'm going to listen to the first three albums back to back. Pure pop. They were the best singles band in the world for a couple of years there. Parallel lines is pretty much perfect. #FridayNightIsMusicNight pic.twitter.com/tg6eMvPK70

— anthony vickers (@untypicalboro) September 2, 2022

(Dog photo by Hollis Rafkin-Sax, edited by Anne Sax, based on a design idea by … me.)

August 16th, 2022

Story as Evidence — Our Story

Edvard Munch, Towards the Forest II, 1915.

JAMA has a long-running and quite wonderful weekly feature called A Piece of My Mind, in which clinicians (mostly physicians) write about the human side of medicine. Not the place for dry descriptions of study designs or laboratory methods, A Piece of My Mind instead welcomes anecdotes, opinions, and emotions.

After all, as Drs. Preeti Malani and Jody Zylke wrote in a 2020 piece celebrating 40 years of the column, “physicians treat patients, not just their diseases, and confront complicated issues and circumstances daily.” In many of the columns, the table is turned, and the physician-writer shares what it’s like to be the patient — the person on the other side of the stethoscope, the scalpel, the chemotherapy infusion, or the psychotherapist’s office.

There’s a real strength to this form of communication, which at times can exceed the influence of even the best-designed clinical trial. While a single case might not stand up to a rigorous statistical analysis, a compelling story about a single patient — either as the caregiver or the person receiving the care — can have remarkable power.

Dr. Louise Aronson brilliantly described this phenomenon in a 2015 submission entitled “Story as Evidence, Evidence as Story.” She wrote:

In the public arena, the N-of-1 personal experience is considered not only data worthy of consideration but also sufficient to establish expertise. With a frequency and consistency that should make those who question the role of anecdotes in discussions of medicine and science rethink their position, a single, well-told story of human suffering trumps the most eloquent explanation of a large-scale trial.

I thought of this “Story as Evidence” phenomenon when hearing that the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, which eliminated the constitutional right to an abortion after nearly 50 years. Naively, I thought growing up that this right to choose would never be taken away.

Why is this relevant to A Piece of My Mind?

Because my wife and I have our own story to tell, now more than 2 decades old, and JAMA was kind enough to publish it this week.

August 8th, 2022

Long-Acting Injectable HIV Therapy for People Who Won’t Take ART?

Atlas. Lee Lawrie and Rene Paul Chambellan, 1937.

HIV treatment is so spectacularly effective that you might be surprised to hear that some people with HIV still have uncontrolled viral replication. We HIV clinicians watch with frustration and sadness as they experience progressive immunodeficiency, complications from advanced HIV disease, hospitalizations, and HIV-related deaths. Plus, while viremic, they continue to risk transmitting the virus to others.

What’s the barrier to successful treatment? In 2022, it’s almost never drug resistance. It’s that they can’t, or won’t, take oral antiretroviral therapy. Excluding those completely out of care (that’s a different problem), I’d estimate from various studies that they typically represent around 5% of a clinic’s population.

The percentage with uncontrolled HIV is higher in places like Ward 86, the safety net HIV clinic at UCSF — around 15% by their estimates. True to its mission, the clinic serves many people struggling with poverty, substance use disorder (especially cocaine and crystal methamphetamine), unstable housing, psychiatric illness, and low medical literacy. That’s why the case series they just published using long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine (CAB-RPV) is so remarkable.

That’s right — cabotegravir and rilpivirine for this highly challenging patient population, a group most certainly underrepresented in the pivotal clinical trials ATLAS and FLAIR.

Out of 132 people in Ward 86 referred for CAB-RPV treatment, 51 started injections. Of these, 39 patients had at least two treatments and were included in this report. The good news: All those with virologic suppression at baseline maintained HIV control during the follow-up, a tribute to the enhanced care provided by the team of clinicians involved in the program.

But by far, the most notable aspect of this report is what happened to the 15 people who were not on suppressive ART — in other words, the group highlighted in the first paragraph of this post, those not taking their meds.

This viremic group had a median CD4 cell count of 99 and a viral load of around 50,000 (with one over a million); a patient with resistance to raltegravir and elvitegravir (harboring the N155H mutation) was also treated. Despite these unfavorable baseline characteristics, 12 of 15 achieved virologic suppression (including the person with N155H), and the other 3 have HIV RNA that has declined by more than 2 log.

Although long-acting CAB/RPV is FDA-approved only for PWH w/ viral suppression, this remarkable case series (new in @CIDJournal) shows it can work also in those with viremia — where it could be a life-saving intervention. Clinical trials urgently needed. https://t.co/GvBQ0AtEvC pic.twitter.com/Z38ybgyLoe

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) August 4, 2022

Wow.

These exciting results notwithstanding, it deserves emphasis that using CAB-RPV for viremic patients takes us way outside the indications outlined in the FDA approval. This specifically stated that the treatment is for those “who are virologically suppressed (HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL) on a stable antiretroviral regimen with no history of treatment failure and with no known or suspected resistance to either cabotegravir or rilpivirine.”

There are plenty of additional caveats about using CAB-RPV in people not taking oral ART. The study includes just a small number of viremic patients, and the follow-up is relatively short (less than a year). We can’t say whether virologic suppression will be maintained, or what proportion will drop out of care and miss their injections, or how many will develop the much-dreaded two-class drug resistance to both integrase inhibitors and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors — resistance that will make subsequent treatments much more challenging. Plus, payers in some regions may not be as generous in covering treatment for a non-FDA approved indication.

It’s also worth remembering that Ward 86 is a special place, hardly representative of most HIV, ID, or primary care clinics. They have tons of dedicated on-site resources to enhance the care of their difficult-to-reach patient population. This includes doctors, nurses, pharmacists, social workers — a veritable army of people available to support and chase down people who might go astray while on HIV therapy.

Example: Two of the patients in this report with unstable housing received injections in the community with “street-based nursing services.” (When I wrote “chase down,” this is what I meant.) How many of us HIV providers have access to this kind of wraparound care? In other words, if you’re in a standard ID or HIV clinical practice, don’t try this at home quite yet.

These caveats notwithstanding, I maintain that this novel use of CAB-RPV is highly important, and that it’s critical it be explored further. Up to this point, our options for people who won’t take oral ART have been highly limited. In desperate cases, we’ve even resorted to feeding tubes to administer ART, these placed during prolonged hospitalizations for AIDS-related complications. If CAB-RPV can provide even half the people who won’t take oral ART an effective option, use in this population will be save more lives than CAB-RPV will through its FDA approved indication. After all, those people are by definition doing well on ART!

The alternative to trying this might be an HIV-related death. And no one in 2022 should die of AIDS without our doing everything we possibly can to get them on antiretroviral therapy.

Even if that includes an unapproved use of cabotegravir and rilpivirine.