An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

June 20th, 2009

More HIV in the Adult Film Industry (Maybe)

From the New York Times last week:

Health officials in Los Angeles said Friday that 22 actors in adult sex movies had contracted HIV since 2004, when a previous outbreak led to efforts to protect pornography industry employees.

(snip)

Occupational health officials have long argued that failing to require that performers wear condoms during intercourse and other acts is a violation of safe-workplace regulations.

But Deborah Gold, a senior safety engineer with the California occupational health department, said violations in the pornography industry were so widespread that the state had a difficult time cracking down.

My first response on reading this was amazement that the number was so small — and, remarkably, that number turned out to be even smaller (1 case) when further details emerged in the LA Times:

Los Angeles County public health officials backtracked Tuesday on their statements last week that at least 16 unpublicized cases of HIV in adult film performers had been reported to them since 2004.

Despite their release of data to The Times describing the cases as “adult film performers,” the county’s top health official acknowledged that the agency does not know whether any of those people were actively working as porn performers at the time of their positive test.

(snip)

The county lacks sufficient information to delve deeply into the cases and still has received no formal report on the most recent case.

“The system we have and the laws we have do not facilitate the kind of contact tracing and verification that we’d like to see,” [LA County Health Officer] Fielding said. “AIDS has been treated separately from other STDs.”

Bottom line here: Aside from this well-researched cluster of cases reported in 2004 in the MMWR, we likely only have a vague idea how many cases of HIV are in, or linked, to this “industry” — which in addition to these semi-regulated companies undoubtedly has a huge underground as well.

And until we get rid of this bit of HIV exceptionalism cited above by Dr Fielding, appropriate contact tracing and partner notification are going to be very difficult indeed.

June 8th, 2009

H1N1: A Tale of Two Practices

As an adult ID/HIV doctor, I must say the clinical impact of H1N1 thus far has been underwhelming, notable more for the calls about prophylaxis or suspected cases than the real thing.

As an adult ID/HIV doctor, I must say the clinical impact of H1N1 thus far has been underwhelming, notable more for the calls about prophylaxis or suspected cases than the real thing.

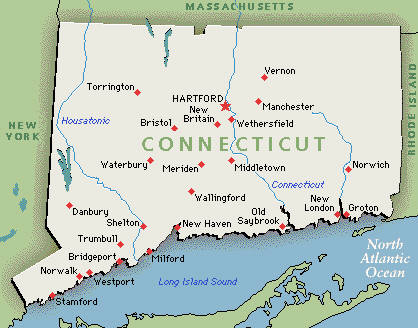

(Last week, one patient with fever and “suspected swine” — hard for people to shake that name — turned out to have … Lyme disease. Ah, New England in June.)

But for my wife, the pediatrician? There’s a full-blown epidemic out there, with outpatient visit volumes way up, and nearly continuous oseltamivir prophylaxis among her staff. As in mid-winter, she and her practice partners are routinely making the influenza diagnosis based on symptoms alone.

And while this report suggests the age cut-off for partial immunity to H1N1 is 60, I suspect strongly — based on our highly-anecdotal, two-doctor-family, completely non-scientific observation — that it’s going to turn out to be quite a bit younger.

June 1st, 2009

“Long-term Nonprogressors” and “HIV Controllers”: Rare Indeed

When giving an overview of HIV pathogenesis to a group of clinicians, Bruce Walker usually asks the assembled if they have any patients in their practice who have undetectable viral loads without antiretroviral therapy.

When giving an overview of HIV pathogenesis to a group of clinicians, Bruce Walker usually asks the assembled if they have any patients in their practice who have undetectable viral loads without antiretroviral therapy.

Generally about three-quarters of the audience has at least one such patient. They are then asked to refer them to his research cohort, which has a goal of trying to figure out why some patients can control HIV replication without needing antivirals.

But how common is this “controller” phenomenon really? And how about its immunologic correlate — people with long-term HIV infection but no significant decline in the CD4 cell count?

Nifty paper in AIDS this month trying to answer this question: Using the French Hospital Database, and starting with over 45,000 potentially eligible patients, the group found that only 69 were “elite controllers” — that is, had >10 years HIV infection, 90% of viral loads <500 cop/mL, and most recent viral load <50 cop/mL.

Stable CD4s were even less common. Only 25 patients were “elite long-term nonprogressors” — that is, had HIV for more than 8 years, CD4 cells > 600, and no CD4 cell decline. That’s an prevalence of 0.05%, or 5 for every 10,000 patients.

Medical students and residents sometimes ask me if a particular patient of mine, asymptomatic and not on antiretroviral therapy, is a “long-term nonprogressor.”

I always respond by asking them what specifically they mean by the term — because as this paper shows, when you look for a truly benign course of HIV infection, you need to look pretty darn hard.

May 28th, 2009

The Paul Farmer Watch

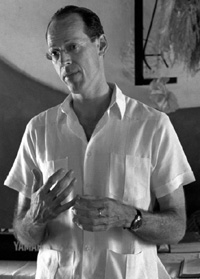

Our pal Paul Farmer keeps racking up the titles:

Our pal Paul Farmer keeps racking up the titles:

Dr. Paul Farmer, a pioneer in improving health services in the Third World, has been named chairman of Harvard Medical School’s Department of Global Health and Social Medicine …

(snip)

Peter Brown, spokesman for Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said Farmer also had been named to succeed Kim as head of the Division of Global Equity at the hospital, a Harvard teaching facility.

Of course what we we’re all wondering is whether he’ll stop with these, or go on also to accept a senior role in the Obama administration:

After weeks of feeling neglected and anxious that no new administrator has been named, USAID and international development community sources tell The Cable they are excited at reports that Paul Farmer, the legendary cofounder of an innovative group that has delivered healthcare to the poor in central Haiti and beyond, is under consideration to head the U.S. aid agency or serve in a top administration international assistance post that would encompass it.

Regardless of his decision, there is a huge irony here — which is that if ever there were a person in our field who couldn’t seem to care less about titles, it’s this guy.

Which is how it should be, of course.

May 13th, 2009

Working While Contagious: Why Do We Do This?

File this under, “physicians behaving badly”: The nearly universal MD practice of going to work while sick.

File this under, “physicians behaving badly”: The nearly universal MD practice of going to work while sick.

The ironic thing is we think we’re being selfless — after all, if we don’t show up, our patients will need to be rescheduled, or someone will need to cover, or some administrative/teaching task will not get done — but let’s imagine for a second that we actually asked our patients what we should do.

Answer: Go home. Get better. Don’t infect me.

Or, to quote the signs that have appeared in our hospital since H1N1 hit, “If you have a cough, sore throat, and fever, please do not enter the hospital unless you are here for care.”

(Patients with these symptoms who are here for care are instructed where to obtain a surgical mask.)

One primary care internist, writing in the New York Times, seems to have kicked the habit:

As a resident, my greatest pride was in never having missed a day for illness. I’d drag myself in and sniffle and cough through the day. Once, I’m embarrassed to admit, I trudged up York Avenue to the hospital making use of my own personal motion sickness bag every few blocks while horrified pedestrians looked on. Now, though, I see the foolishness of this bravura.

Sadly, I think she’s in the minority.

May 7th, 2009

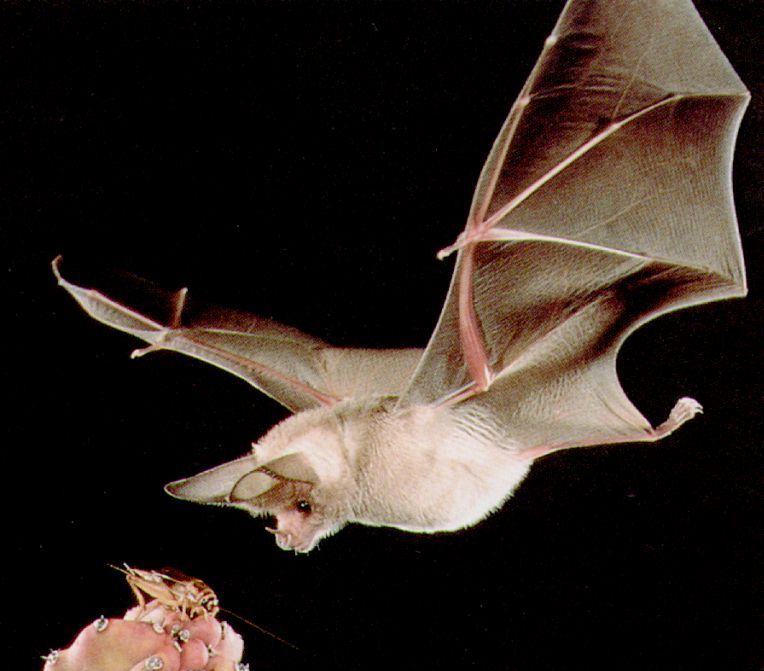

Human Rabies from Bats: Another Look at the Numbers

The gang from Canada is at it again, reviewing human rabies cases from bats and trying to make some sense of the data.

The gang from Canada is at it again, reviewing human rabies cases from bats and trying to make some sense of the data.

(For a summary of their outstanding prior paper in CID, read this.)

But before we get to their latest masterwork, here are some questions to ponder. While doing so, keep in mind the practice of giving the rabies vaccine to a person with “bedroom exposure to a bat while sleeping, without evidence of direct physical contact”:

- Are you more motivated by avoiding an “error of omission” (a mistake from not doing anything) than an “error of commission” (a mistake from doing something)?

- Do you ever envision yourself being named in a lawsuit for failure to provide preventive therapy?

- Do you sometimes imagine yourself cited in a newspaper as the doctor who said, “that isn’t necessary”, only then to have the patient in question be the one in a zillion who gets rabies? (“We called Dr. Freepner, and he said not to do it. Later, she was dead.”)

- Do you feel you have a moral imperative to provide preventive therapy for a condition that will likely be fatal, no matter how unlikely it is that a patient will develop it?

- Do you think cost, limited supply, and personnel issues should always be secondary considerations when making decisions about an individual?

- When you read official guidelines that state that preventive vaccination “can be considered” in low but not zero risk circumstances, do you interpret that to mean it should be given?

- Did you ever find yourself doing something clinically that you just knew made no sense, yet you did it anyway?

I suspect we all could answer “yes” to some, if not all, of the above questions. These are not rational decisions, they are emotional ones.

Hence this latest paper is such a joy to read. It provides yet more evidence that a policy of giving the rabies vaccine to patients with a “bedroom bat exposure” but no contact is, to be blunt, pretty ridiculous. Some of the key numbers:

- Based on a telephone survey done in Quebec, fewer than 5% of people with such bat exposure get vaccinated.

- The estimated incidence of rabies due to this exposure is 1 case per 2.7 billion person-years.

- The number needed to treat to prevent a single case of human rabies from bedroom exposure (but no contact) is around 2.7 million.

- If all potential exposures were investigated and evaluated fully — after all, this is recommended in the guidelines, right? — this would require 49 physicians, 491 nurses, and 259 veterinarians working full-time for a full-year. And this estimate does not even include administration of the rabies vaccine!

In short, what we are doing is absurd — we are giving preventive therapy to a small proportion of the potentially exposed only because they show up, and because we can. It has very little to do with preventing actual cases of rabies, but it sure makes us and our patients feel better.

But if it’s indicated for those who show up, what about the 95% who don’t? Solid quote:

Failure to intensely pursue a greater proportion of eligible persons then becomes paradoxical public policy: a recommendation that is known to be sustainable only if ignored by most eligible persons is of doubtful usefulness and questionable ethics.

So what are we to do? The authors conclude that the recommendations for rabies vaccine for bedroom or other occult exposures “be reconsidered.” I read that to mean, “be scrapped.”

And someone please point me in the direction of why some irrational physician behavior is so hard to shake.