An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

July 3rd, 2011

Proof That We Are Not French

In case you were worrying about fading American national identity as we celebrate July 4, did you see this detail on a recent E. coli O104:H4 outbreak from France?

In case you were worrying about fading American national identity as we celebrate July 4, did you see this detail on a recent E. coli O104:H4 outbreak from France?

More recently, at least 15 people in Bordeaux, in southwestern France, appear to have been infected with the strain found in Germany. Most of them have been linked to a day care center in Bègles, a suburb, where the victims apparently ate gazpacho garnished with sprouts.

I think it’s safe to say that among day care centers in the United States, the number serving gazpacho garnished with sprouts is approximately the same as those serving Chateau Lafite as the drink to accompany chicken fingers with fries.

Or should that read, “avec frites.”

June 24th, 2011

Reflections on Levofloxacin as it Goes Generic

With the news that a generic form of levofloxacin has just been approved by the FDA, some thoughts about this remarkable antibiotic:

With the news that a generic form of levofloxacin has just been approved by the FDA, some thoughts about this remarkable antibiotic:

- When it was first approved in 1996, levofloxacin was the first oral antibiotic that really covered all common causes of community acquired pneumonia. Strep pneumo, H flu, mycoplasma, legionella, chlamydia — check, check, check, check, and check. Doctors realized this, of course, and prescribed it like mad.

- Grave prognostications about the threat of pneumococcal resistance to quinolones invariably followed — but this never materialized to a sufficient degree to change practice, at least not in the United States. It has remained unusual to find one of these levofloxacin-resistant pneumococci in clinical isolates, and surveillance reports show that such resistance is surprisingly rare.

- However, rates of gram negative (especially) and Staph aureus resistance to quinolones just keep going up and up. Amazing, these bugs are smarter than we are! What a concept! These UTI guidelines cite “collateral damage” of using quinolones for uncomplicated cystitis — a wise move.

- These cautionary notes notwithstanding, some medical services think it’s mandatory that every patient receive at least one dose of levofloxacin prior to hospital discharge. I made that up, and have mentioned it before, but you get my point — this is still one popular antibiotic. See #1, above.

- As numerous other quinolones fell by the wayside due to safety issues, levofloxacin has remained overall quite safe. Temafloxacin, trovafloxacin, grepafloxacin, sparfloxacin, gatifloxacin — gone, but not forgotten. Trivia question for detail-obsessed ID types (which means all of us): Why were each of these pulled off the market? And what were their trade names? (Hint: several of the trade names sounded like they were lifted right from a science fiction novel.*)

- But even though it’s relatively safe, levofloxacin does have some serious side effects. Probably the worst of these is the tendon rupture/tendinitis issue — deserving of the dreaded “black box” — but I’ve also seen anaphylaxis, delerium, QT prolongation, photosensitivity, and many many cases of C diff. Bottom line is that this is a drug: we humans did not evolve to have levofloxacin coursing through our system. (Tell that to cardiologists about statins.)

- In vitro, levofloxacin is neither the most active gram-negative or gram positive quinolone. Those would be ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin, respectively. But it hasn’t really seemed to matter much, has it? See #1 (again), above.

- Presumably, the availability of generic levofloxacin will eventually eliminate the levofloxacin to moxifloxacin swap often mandated by payors. Since our hospital has levofloxacin as its preferred respiratory quinolone, it has set up the peculiar practice of using levofloxacin during the hospitalization, then changing to moxifloxacin on discharge. This can’t make medical sense — they are not identical after all — so I for one will be glad to see this exchange come to an end.

*An experienced starship pilot, Raxar expertly navigated his Tequin-400 aircraft through the high mountains of Trovan. This was no easy task, as the planet’s distinctive craggy peaks were nearly completely obscured by thick clouds of Omniflox — the highly-toxic gas released from volcanic eruptions. Off in the distance, he could see the bright lights of the capital city Zagam. “Home at last,” he said out loud. But Raxar spoke too soon, for little did he know that this final leg of his journey would take him to worlds unknown …

June 15th, 2011

Hockey Helicobacters

Today’s ID/HIV items come to you courtesy of a winter game being played during a summer month:

Today’s ID/HIV items come to you courtesy of a winter game being played during a summer month:

- So it appears that community-based care of HCV augmented by telemedicine is just as good as traditional clinic visits to specialists. My first thought on reading this important paper is that there are undoubtedly lots of ways to incorporate technology into patient care for the better, extending the reach of specialty services. But — and call me a cynic — if in a fee-for-service world, specialists get paid for services rendered during office visits, and not for setting up and managing telemedicine, which one do you think they’ll choose? To quote the editorialist: “It is also important to develop models for financing this innovative care model, with respect to both the specialists and the primary care providers involved.” Emphatically agree.

- Here’s a comprehensive list of sprout-related outbreaks, if you’re keeping score.

- In the flurry of recent drug approvals in the ID/HIV world — ceftaroline, nevirapine XR, rilpivirine, fidaxomicin [update: apparently not available until later this summer], boceprevir, telaprevir, generic zidovudine/lamivudine — I always wonder what the early anecdotal experience will be from experienced providers. Any first impressions? So far I’ve used ceftaroline and rilpivirine, not the others.

- Did you see this latest “scorecard” on states’ compatibility with the 2006 HIV Testing Guidelines? It includes three suggested key elements of HIV consent to facilitate testing: 1) changing from opt-in to opt-out 2) allowing general consent for care to include HIV testing, and 3) permitting written or oral consent. Good news: now only 4 states per this report have HIV testing laws outside these recommendations. In fact, there is only one state that is incompatible with all three components. And that state is … Massachusetts, thank you very much! (FYI, we’re working on changing this.)

- Can’t believe I missed commenting on this remarkable paper in Lancet ID, which clearly documents the clinical relevance of transmitted drug resistance, as well as the importance of baseline genotype testing in reducing the risk of treatment failure. It also hints that in the presence of any transmitted resistance, a boosted PI-based regimen might be the best choice, at least for virologic outcomes. Makes sense. Further commentary in Journal Watch AIDS Clinical Care here.

And as you watch tonight’s Stanley Cup final, and thoughts turn to winter, you might note that the 2012 CROI dates and location still have not been announced. Are the conference organizers awaiting the outcome of tonight’s game to decide where to go? Both Boston and Vancouver in February would be suitably cold options.

June 9th, 2011

E. Coli, ID Doctors, and Fear of Infections

This was going to be about the shiga-toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) outbreak in Germany, and I promise to get there eventually.

This was going to be about the shiga-toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) outbreak in Germany, and I promise to get there eventually.

But to start: One very useful concept from psychiatry is “reaction formation.” For those of you who have forgotten your college Psych 101, here’s the definition:

A psychological defense mechanism in which one form of behavior substitutes for or conceals a diametrically opposed repressed impulse in order to protect against it.

Some examples: the person who controls criminal impulses by becoming a cop, or someone with a fear of heights who fixes cell phone towers.

How about ID doctors? Do some of us choose this field because we’re scared of catching nasty bugs?

Undoubtedly yes — I have one colleague who, at great personal expense, had all the windows, screens, and vents replaced in his house because he saw some bats flying around his neighborhood on a warm summer evening. He has been observed to wear a surgical mask when he looks in his patients’ ears (“just to protect you,” he lies), gets the tempura at sushi restaurants, and he wouldn’t travel to a developing country even if you gave him, for free, round-trip first-class airfare and the best suite in this resort.

He’d deny it, but I strongly suspect his choice of specialty is directly related to his fear of contagion. (That interpretation was gratis. You’re welcome.)

But then there are plenty of us who are relatively cavalier about infectious risks. In one famous example, a certain sainted ID doc (initials PF) never received vaccination for hepatitis A despite having probably the highest travel/work related risk on the planet. The result: a fairly prolonged hospitalization from acute hepatitis A. Boy was he sick. (Read all about it in this excellent book.)

Even more impressive, there are those who bravely volunteer for outbreak investigations, even for incredibly scary, mysterious, or untreatable diseases. Two recent examples that come to mind are SARS in China and the extensively drug resistant (XDR) TB cases in South Africa.

With the caveat that any self-reflection is likely to be biased, even in a highly psychoanalytic milieu (my father is a psychiatrist), I consider myself as one of those ID doctor on the less-worried side of the spectrum. I’ll take my chances with the bats (unless one actually bites me …), choose whether to eat or not to eat sushi based on taste (not because of infectious risk), and believe that most Travel Clinics cater predominantly to the worried-well — or, if you want to be less nice about it, the paranoid. Plus, I have never feared getting HIV from patients, even in the 1980s when we knew a lot less about transmission than we do today.

On the other hand, I doubt very much I’ll be raising my hand anytime soon to volunteer for on-site evaluation of an Ebola outbreak.

But getting back to this toxin-producing E. coli: here’s one infection that I do take pretty seriously — ok, I admit it scares me — and confess to being kind of rude about it.

You don’t want me at your cookout if you plan to serve hamburgers rare, as I will undoubtedly be obnoxious about sharing my fears not just with you but all the other guests as well. Maybe it’s because of stories like this one. Or perhaps because my wife has discussed with me a few truly harrowing examples of previously-healthy kids from her practice who ended up on dialysis. Or that antibiotics not only don’t help, they even increase the risk of disease. And yes, I also saw the movie “Food Inc.” (review here), which really does make you understand why ground beef in particular is so risky.

So as they investigate the source of this terrible outbreak in Germany — which appears to be non-meat related, at least based on what is known right now — do yourself a favor, and cook those burgers all the way through, and skip the sprouts. (I know burgers taste worse cooked this way, but most people don’t like sprouts anyway.) And take some comfort in the fact that at least in the USA, cases of STEC from the O157:H7 strain are actually down (Journal Watch summary here). Let’s hope it stays that way.

June 4th, 2011

HIV Epidemiology and Something Even Many Smart Medical Students Don’t Know

Periodically I like to give an informal quiz to the medical students about HIV epidemiology. It’s a multiple choice question that goes something like this:

Periodically I like to give an informal quiz to the medical students about HIV epidemiology. It’s a multiple choice question that goes something like this:

Based on the recent epidemiology of HIV in the United States, in what group are new cases of HIV infection rising the fastest?

- Men who have sex with men (MSM)

- Injection drug users (IDUs)

- Heterosexual women

- Some other group

(Correct answer: #1.)

Now these are smart kids. Many of them have done impressive things before starting med school, including a bunch who have even worked in the HIV field (especially global HIV). Yet despite these brains and experience, you’d be amazed how often they choose the wrong answer, most commonly choosing #3 (a group in whom incidence is essentially flat or declining) or #2 (injection drug use HIV in the USA is, thankfully, disappearing).

On the 30th Anniversary of the first report of what is now known as AIDS, the MMWR has released its latest HIV Surveillance report. And, as in pretty much every year for more than a decade, here are the facts:

Surveillance data show that the proportion of HIV diagnoses occurring in MSM continues to grow. HIV incidence among MSM has increased steadily since the early 1990s. In 2009, MSM accounted for 57% of all persons and 75% of men with a diagnosis of HIV infection... Syphilis and gonorrhea are endemic among MSM; outbreaks or hyperendemic sexually transmitted infections have been reported from many communities where HIV infection also is prevalent, further increasing the risk for acquiring and transmitting HIV.

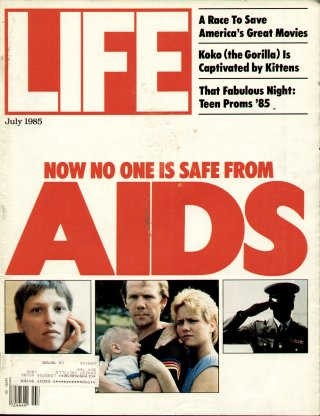

I’m not sure why this isn’t more widely known (certainly we HIV/ID specialists know it), but I have a theory. Sometimes a story has media “stickiness”, and once it’s out there, it’s hard to get rid of it. When AIDS first hit, it was overwhelmingly a disease of MSM and IDUs; quickly it became apparent, however, that it was a sexually transmitted infection so that women were at risk too. This was a big media story — famous Life Magazine cover shown above — and somehow this has never disappeared.

It’s kind of like, “tuberculosis is making a comeback in the USA” when, in fact, TB rates are historically low. The TB Comeback is just too sticky. Same thing with the generalized HIV epidemic in this country which, if you take a look at this incredibly cool map, has never happened.

Take home message: HIV prevention and testing efforts should be maximally deployed where the epidemic is still raging. Here in the USA, that means MSM and/or communities of color.

June 2nd, 2011

Original XMRV/CFS Paper Almost, Sort-of Retracted by Science

From the pages of Science

In this week’s edition of Science Express, we are publishing two Reports that strongly support the growing view that the association between XMRV and CFS described by Lombardi et al. likely reflects contamination of laboratories and research reagents with the virus … Because the validity of the study by Lombardi et al. is now seriously in question, we are publishing this Expression of Concern and attaching it to Science’s 23 October 2009 publication by Lombardi et al.

In the roughly year and half since this story first broke on XMRV as a possible cause of CFS, there have been literally dozens of scientific papers (published, unpublished, and presented), many editorial comments, conference proceedings — and probably thousands of blog posts (I’ve added to the traffic) and impassioned comments from people suffering from this condition.

As I’ve noted before, perhaps the best coverage in the non-medical/science press has been over here in the WSJ.

And while there is now significant “concern” about this XMRV/CFS association, there is little doubt about the need for more research on CFS. One problem is that the XMRV debate could become a distraction in the search for other possible causes, host factors, diagnostic tests, and treatments. Let’s hope that doesn’t happen.

From the

From the