An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

January 25th, 2025

Let’s Hope the MMWR Resumes Publication Sooner Rather Than Later

To us specialists in Infectious Diseases, there are certain verities we hold near and dear to our hearts:

- Antibiotics are miracle drugs, but the bugs will become resistant if we don’t use them responsibly.

- Certain childhood vaccines (e.g., measles, polio, H flu type B) stand as some of the greatest scientific accomplishments in human history.

- To understand infectious risks, you have to have good data, carefully sourced and analyzed.

Number 3 is why this week’s non-publication of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) came as such a shock. MMWR is the CDC’s primary way of publishing and communicating important data for public health. It didn’t go out because of a communications pause at federal health agencies issued by the new administration. The gap in publication marks the first time in its more than 60-year history that the CDC didn’t release a new issue.

Want an example of how useful the MMWR is for us ID people? Here’s a good one:

Highlighted in red, dear friends, is the first report of the disease now known as AIDS occurring in five previously healthy gay men in Los Angeles. The text from this account has always struck me as a perfect example of careful but prescient scientific reporting:

The occurrence of pneumocystosis in these 5 previously healthy individuals without a clinically apparent underlying immunodeficiency is unusual … All the observations suggest the possibility of a cellular immune dysfunction related to a common exposure that predisposes individuals to opportunistic infections.

Spot-on accurate. The second MMWR detailing more AIDS cases occurred less than a month later. Remember, these publications appeared 2 years before the discovery of HIV, the virus that causes the disease.

Subsequent MMWR reports on the rising incidence of AIDS, the populations at risk, and the strong epidemiologic evidence for modes of transmission played key roles in figuring out what was happening on a national and global level. We knew even before the virus was discovered that sexual, perinatal, and blood-borne infection were all implicated, and that household and other “casual” contact posed little, if any, risk.

Want more recent examples of infectious threats all reported in MMWR? A partial list:

- SARS

- MERS

- Zika

- Ebola

- Chikungunya

- Candida auris

- Mpox

- H5N1 avian influenza

- Innumerable food-borne outbreaks

- And yes, of course, COVID-19

I put COVID-19 last because I strongly believe this is the primary motivation for the communications pause issued by the new administration. The pandemic was so horrifically disruptive — so traumatic — to our society that we’re still grappling with the best way to deal with it.

And one unfortunate coping mechanism is the urge to scapegoat individuals and organizations for what happened. The CDC and its publications were often in the center of this storm, and some now want to blame them for all that they were unhappy about.

Was CDC perfect? Of course not. But they tirelessly worked to get things right, and reported abundant COVID-19 data on case numbers, hospitalizations, deaths, and vaccinations that we all turned to regularly. To expect, in hindsight, that they would do so infallibly is setting an impossible standard — one no organization, government or otherwise, can meet.

Apparently, the MMWR staff are still at work, so let’s hope that the pause in communication is brief. There always will be infectious threats out there, with H5N1 avian influenza now being foremost on our minds. It’s only through careful and regular reporting of data that we can face these threats responsibly.

January 11th, 2025

Ten Interesting Things About Norovirus Worth Knowing

For reasons unclear to all, we’ve had quite the run (!) on norovirus cases in the United States this winter. Seems like everyone knows someone who’s been taken down by this nasty illness, and this crowd of miserable people includes one of my medical school classmates, a good friend who texted us about her experience.

For reasons unclear to all, we’ve had quite the run (!) on norovirus cases in the United States this winter. Seems like everyone knows someone who’s been taken down by this nasty illness, and this crowd of miserable people includes one of my medical school classmates, a good friend who texted us about her experience.

Thanks for sharing, Diane, speedy recovery!

So here are ten interesting facts worth knowing as you wisely head to the sink to wash your hands again before eating:

1. It is the leading cause of acute gastroenteritis in the world. This chart-topping characteristic of norovirus is probably even more impressive now that the rotavirus vaccine is available, dropping childhood cases from that virus dramatically.

In case you’re wondering, “acute gastroenteritis” just means diarrheal disease of sudden onset that lasts less than 2 weeks and may be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and fever.

2. It was discovered after studying stored stool specimens collected during a community outbreak from 1968. That outbreak involved half (!) the students at a school in Norwalk, Ohio — hence the name, “Noro” gets its first syllable from “Norwalk”. I guess the citizens of that town didn’t want to be remembered for this dismal week.

Before the identification of virus, scientists strongly suspected a transmissible agent for this illness for obvious reasons. Not only was the attack rate so high in that school, but some of the family members of those students (who had not been in the school) came down with a similar illness.

Researchers then conducted some highly disturbing (from an ethical standpoint) human challenge experiments from specimens collected during this same outbreak, proving that it was, in fact, contagious. Can you imagine trying to get studies like this through a human subjects committee today? Awful.

The actual publication of the pivotal paper documenting discovery of the virus wasn’t until 1972, when advances in electron microscopy allowed identification of the culprit critters from four years earlier, shown in this image:

3. Cases of norovirus peak in the winter months. In fact, the illness was once called “winter vomiting illness” due to this seasonal peak, with this generic term used prior to the discovery of the causative agent. Why winter? Humans gather indoors, huddling together against the cold, passing respiratory viruses between each other in the air, and viruses like norovirus in contaminated food, water, and surfaces. Fun times!

It was also called “non-bacterial gastroenteritis” to distinguish it from salmonella, shigella, and other causes of diarrhea that could be diagnosed by cultures. These “non” labels in medicine have always amused me — describing something by what it is NOT. You know, “non-A, non-B hepatitis” before we knew about hepatitis C, or “non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM),” a term still in broad use despite way more NTMs than TMs. Weird.

(I still miss NASH — non-alcoholic steatohepatitis — for fatty liver, an entity that seems to change its name every week.)

4. Infamous sites for norovirus outbreaks include cruise ships, daycare centers, recreational water parks, military barracks, nursing homes, and college dormitories. But especially cruise ships — go ahead, check out that link, I’ll be here when you get back.

… (waiting patiently) …

OK, now that you’ve seen the list of reported cruise ship outbreaks just in the past year, do you still want to take that winter cruise? Fact: any place or situation that people gather in close settings, and where contaminated food, water, and surfaces are hard to control, can trigger these outbreaks. How about particular foods? Oysters are often mentioned, which is no surprise at all, giving me an additional reason to avoid these slimy beasts*.

(*Easy for me to say since I don’t like them. Hardly a sacrifice. Feel very fortunate it’s not chocolate, or pizza.)

5. The incubation period is typically 24–48 hours after exposure. However, this doesn’t mean a person is “in the clear” after a couple of days if they don’t catch it in a household, on a cruise ship, or a dormitory that has active cases, for reasons that will be plainly evident in the next scary facts about the durability and ubiquity of norovirus in our world.

6. While norovirus shedding peaks during the acute illness, the virus can still be detected in stools for weeks in many people, small amounts can cause disease, and it’s devilishly hard to kill. The median time to loss of the virus is a month. Wow. A decent proportion of asymptomatic children shed the virus — nearly half in a study of kids in Mexico.

Plus, it’s an incredibly hardy virus — it resists freezing, heating to 60°C, and is not eradicated by alcohol-based hand sanitizers. I’ve heard this last phenomenon is because of the durable norovirus capsid, versus the much more fragile envelopes in other viruses, such as SARS-CoV-2 and influenza. I’m sure virologists have a much more sophisticated explanation.

One might wonder, reading these facts, why everyone doesn’t get norovirus all the time, or at least once every year. It comes down to those basic principles of infectious diseases, which are host factors (immunity, genetics, stomach acidity), inoculum size (how much virus found its way to you), and luck. Secondary attack rates might be high, but remember that sentinel outbreak in Norwalk — “only” half the students got it.

(For the record, my friend Diane’s husband is doing just fine. So far.)

7. After 1–2 days of utter misery from norovirus gastroenteritis, most people start to improve. During recovery, it’s not uncommon to have a week or so of feeling wiped out as one regains hydration and nutrition, but the general trend is favorable despite some ongoing gastrointestinal symptoms.

As with all infections, the disease is more severe for those at the extremes of age and people who are immunocompromised. For the latter group, illness can be prolonged, lasting weeks or even months, leading to profound weight loss.

8. There is no antiviral treatment for norovirus. Treatment is “supportive”, with the goal of maintaining hydration and getting at least some calories in during the acute phase. Remember, even people with cholera — the most notorious and life-threatening diarrheal disease of humankind — can absorb fluids when given liberally. So hydration is key.

What about during recovery? There’s lots of advice out there on the interweb, with variously recommended diets (e.g., bananas, rice, applesauce, toast — “BRAT” — clear broths, avoiding dairy products and spicy foods, etc.), but the reality is that we don’t have good evidence for any particular diet. I tell patients basically to eat what they want, in moderation, and to listen to what their bodies are telling them. The return of hunger is an excellent sign a person is on the mend.

9. The diagnostic test of choice for norovirus is stool PCR. Many laboratories now do molecular tests first — not cultures — to evaluate the causes of diarrhea. Since it’s so common, norovirus is included in all the multiplex panels that test for multiple pathogens.

The increased use of molecular testing no doubt explains at least in part the increased incidence of this infection. But on the flip side, the vast majority of cases are never diagnosed — so whatever figures we see on incidence are no doubt a massive underestimate.

10. Prevention strategies include frequent hand washing, cleaning contaminated surfaces, and isolation of symptomatic patients. As noted above, despite both pre- and post-symptomatic viral shedding, the highest risk time for transmission is during the symptomatic phase of the illness. Will we ever have a norovirus vaccine? Perhaps, though there are plenty of obstacles.

So that’s 10. Actually way more than 10, see how your subscription brings you added value?

And as an additional bonus, listen to my brilliant colleague Dr. Mike Klompas speak in our postgraduate course. Check out his #1 tip for infection control — for norovirus, it’s gold!

January 3rd, 2025

On the Inpatient ID Consult Service, Oral Antibiotics Have a Rocky Road to Acceptance

Home IV antibiotics are not fun — just look at her face. (Image: Pixabay)

Having just completed a stint doing inpatient ID consults, I came away impressed with three things:

- Staph aureus remains the Ruler of Evil Invasive Pathogens in the hospital setting.

- You can “jinx” a holiday season by saying it’s usually quiet on Christmas. This year it sure wasn’t quiet, hoo boy.

- Some surgeons aren’t ready to accept the evidence about oral antibiotics being just as good as intravenous (IV) for their patients with severe infections.

Note I wrote some surgeons — not all. But with apologies to authors of the POET and OVIVA studies, and in particular to Dr. Brad “Oral is the New IV” Spellberg, who has been a leader in this space, I bring you now a blended version of several conversations I had with surgical colleagues when I recommended oral antibiotics for their patients:

Me: I heard from your resident that you wanted a PICC line for Mr. Smith. Did you see our consult note?

Surgeon: Thanks for following him. No, didn’t read it — what did it say?

Me, not at all surprised that the attending surgeon didn’t read our Masterpiece: We recommended that he go home on trim sulfa, one double-strength tablet twice daily. (I might have said Bactrim. Ok, I did.) The organism is susceptible, and it has excellent oral absorption. That way we can spare him the PICC line and all the risks and hassles of home IV therapy.

Surgeon: This was a very severe infection — I’d prefer we be as aggressive as possible in treating it.

Me: Understood. But there’s literature now showing that oral antibiotics are comparable to and safer than IV. I’m especially comfortable in recommending it when there is a high GI-absorption option like Bactrim, a susceptible bug, and there has been source control, as in this case.

Surgeon: Thanks for sharing that — I’m not up on the ID literature, but this infection threatened to get into the joint (or bloodstream or CNS — it’s a generic conversation). In the OR, we drained frank pus*, and had to copiously** irrigate the site with 3 liters of sterile saline.

(*I always felt bad for people named “Frank” when I hear this expression.)

(**Surgeons frequently use the word “copiously” when they irrigate infections. And how do they decide on the number of liters to use?)

Me: Yes, I understand it was bad. But it sounds like you got it all — that’s probably the most important thing. Another thing, he’s taken Bactrim before, and we know he tolerates it well.

Surgeon: Maybe use orals for a milder infection, but not for an infection this severe. I told him after the surgery he’d be going home on IVs. If we use oral antibiotics and it fails, I’d feel bad we didn’t attack this as hard as possible with IV antibiotics.

Me: Ok, we’ll set up the home antibiotics.

Surgeon: Great, thanks so much. Really appreciate your help.

Me: No problem. He’ll go home on 6 weeks of IV colistin.

(That’s an ID joke, ha ha. It really was ceftriaxone.)

A few comments about this exchange.

- It’s entirely friendly. We both want what’s best for the patient.

- The surgeon has already made up his mind before consulting us that IV is preferred over oral antibiotics.

- There is deep anxiety about oral antibiotics not being “aggressive” enough with a “severe” infection, with the concern about an error of omission rather than commission. Meaning, a bad outcome by doing less outweighs concerns about a bad outcome by doing more, which is why I bolded this sentence, and repeat it here: “If we use oral antibiotics and it fails, I’d feel bad we didn’t attack this as hard as possible with IV antibiotics.”

This last point gets to the core of this debate. Surgeons, who by their very nature are quite active in their day-to-day practice, may not comfortable with what they consider a less invasive approach. Intravenous antibiotics are more challenging, more intensive, typically reserved for inpatients or critically ill people, hence (they think) they must be better.

This is a particularly tough nut to crack. And I get it — if an infection is severe, don’t we want to treat it as aggressively as possible?

The problem with this line of thinking is that it ignores good clinical evidence (including randomized trials and well-done observational studies); it does not factor in the risks, hassles, and cost of IV therapy; and it forgets the important principle Brad often cites, which is that the bacteria don’t care how the antibiotic got there — just that it got there.

In some ways, we’ve fostered the surgeon’s view by taking on the management of home IV therapy — often called Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy, or OPAT — as a core responsibility of us specialists in Infectious Diseases. After all, who knows antibiotics better than we do?

But this has insulated them from the problems. If we had each surgeon manage OPAT for their patients, it would open their eyes about misplaced monitoring labs, clotted and infected lines, upper extremity DVTs, failed home deliveries of medications, confused care providers at home, capricious vancomycin levels, and miscellaneous other mess-ups that are an unwelcome part of home IV therapy.

I have a hunch that if Dr. Orthopod P. Neurosurgeon had to manage these and myriad other OPAT issues, they’d be quite willing to consider an oral option if we told them a good one existed.

December 28th, 2024

Notes from a Trip to China

Thanks to Glenn, tour guide extraordinaire, for this picture of the Forbidden City! (Yes, it was cold.)

Here are some observations from a recent trip to China, a country I’d never visited before. It was an 8-day trip related to my editor role at Clinical Infectious Diseases (there is a Chinese edition) and my particular area of focus within Infectious Diseases (HIV), so I’ll start with some epidemiology and medical stuff and wrap up with some non-medical observations.

Big picture — it’s an amazing country, well worth visiting, with dynamic city life, historic sites, incredible food, and so many people. Very grateful for the opportunity to visit.

Two caveats ahead of time — this was just one trip, an “academic exchange,” with lectures and hospital visits. So my experience can hardly be considered fully representative of this complex and giant country. Second, that 13-hour time difference scrambles the brain a bit, so it’s possible (likely) I got some of this wrong. Corrections welcome from the true China experts out there!

Medical and Epidemiology Section

Over 1.4 billion people live in China — that’s over a billion more than in the USA (334 million), in a country roughly the same geographic size. Must keep that in mind when interpreting any epidemiologic data.

China lost the “most populous country in the world” title recently to India, which just edged it out. Population growth has stopped, even after the end of the one-child policy. Like many prosperous nations, young adults in China don’t want to have big families anymore.

China still has just over 100,000 new HIV diagnoses a year. If you think about our 38,000 new cases/year in the USA, and adjust for our respective country’s populations, their incidence appears to be similar to ours, perhaps a bit lower.

Sexual transmission of HIV dominates the current China HIV epidemic in most regions. People told me it was, like the USA, predominantly in men who have sex with men — but it’s hard to find this information in official figures. It’s an enigma!

Despite a big scale-up and wide availability of HIV testing, the late diagnosis of HIV remains a huge problem. Approximately a third of new HIV cases are diagnosed when the CD4 cell count is < 200. As a result, they still have plenty of people diagnosed during a hospitalization for opportunistic infections.

The spectrum of opportunistic infections they see includes the full range of bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, and viral pathogens. One difference is that southern China is an endemic region for Talaromyces, which is quite uncommon in North America.

There’s very little use of PrEP. This is a big opportunity for HIV prevention, as late HIV diagnosis means not just symptomatic HIV disease and opportunistic infections, it also implies many years of potential HIV transmissions prior to getting on suppressive HIV therapy.

The doctors in clinical practice are unbelievably busy, busy in ways we could never endure in the USA. Doctors told me that some days they saw 50 or more patients. Overnight shifts in the hospital had similar numbers.

One Chinese doctor cited a visit to the USA where she heard doctors complain about being too busy with an HIV clinic that had 10 patients scheduled during an afternoon in clinic. She found that highly amusing.

(Hey — I’d find that busy too!)

The incredibly high demand for medical services, and the required brevity of the clinical visits, has engendered a strain between doctors and patients, and plenty of distrust. Several people mentioned this to me.

The government provides ART and laboratory monitoring for all people with HIV. This includes standard lab tests and more sophisticated molecular tests, if indicated.

The default government-supplied first-line treatment is a four-pill tenofovir DF, lamivudine, and efavirenz regimen. (The efavirenz comes as two 200 mg pills.) This is why a randomized clinical trial comparing it to BIC/FTC/TAF was ethical — efavirenz-based therapy is still standard of care in China.

People can pay to get integrase-inhibitor based first-line regimens that include either bictegravir or dolutegravir. The price is much lower than in the USA.

Transmitted HIV drug resistance is a growing problem. Not surprisingly, it’s NNRTI resistance that’s the issue, which is exactly what happened here in the 2000s.

Non-Medical Section

Cash in China is gone. Everyone pays for things electronically. This is true in the fanciest hotels, shops, and restaurants, at the humblest street stalls selling inexpensive souvenirs, marinated tofu rolls, and chili noodles, and everything in between. The only “cash” I saw was a replica of a bill on a decorative airline ticket.

An app does everything. That app is WeChat — it pays for things, yes, but so much more. It also consolidates your spending history, chats, shared photos, locations, call records, probably your dog’s birthday. It’s all there in one multi-purpose location.

The government monitors everything, and everyone knows this. That includes, of course, WeChat. Sure must make it convenient for them to see what you’re up to!

Cameras are everywhere. I walked into a hotel for a meeting, one I wasn’t staying at, and a camera quickly picked up my face in the elevator, projecting it on a screen next to the number pad and highlighted it.

The cities I visited were unbelievably clean. I visited Guangzhou, Hangzhou, and Beijing. These are big cities, with plenty of people and high population density. You’d think that would lead to plenty of garbage on the streets and overflowing trash cans, but I saw zero of both. It was wonderful.

The cities I visited were unbelievably clean. I visited Guangzhou, Hangzhou, and Beijing. These are big cities, with plenty of people and high population density. You’d think that would lead to plenty of garbage on the streets and overflowing trash cans, but I saw zero of both. It was wonderful.

(Quick aside: Interesting contrast to my hometown New York, where bags of garbage are put out on the street on a regular basis, and trash bins are few and far between or over capacity — or non-existent! New York’s garbage certainly must be quite a shock for visitors from China.)

The cities are unbelievably safe. It was wonderful (again). I strolled down some packed pedestrian passages, brimming with people looking at shops, tasting street food, watching the occasional public dancing group. I asked the person I was walking with — who was wearing his backpack on his back — if he ever worried about pickpockets. “Doesn’t happen here,” he said.

(Another aside — Barcelona is one of my favorite cities in the world. But can you imagine how long your wallet or cell phone would last in your backpack if you wore it on your back on Las Ramblas?)

The quality of rail travel — subways and high-speed trains — is light years better than ours. Public transportation is very affordable and (not surprisingly) very crowded. The airports are gleaming and efficient.

Car traffic in the big cities is quite dense (like ours) but exacerbated by an enormously wide range of vehicles (cars, trucks, scooters, mopeds, bicycles both manual and electric) using the same roads. Seems like half the cars are electric (green license plates), featuring many brands not available here.

Tourist sites are very popular, with most of the tourists Chinese — book ahead! And don’t be fooled by the “empty” look of the Forbidden City in the picture at the top of this post — that was due to the skilled photography work of Glenn, my erudite tour guide, who knew the perfect vantage point for every photo. The place is huge, by the way — that picture is probably 10% of the total area.

Intense security is part of the process of entering famous sites. Don’t forget your passport, which will be scanned or at the very least reviewed.

Tea is ubiquitous. This is the drink that accompanies every meal.

Starbucks is ubiquitous. This and the previous comment are not oxymorons. Tea is for meals, Starbucks for other times of day. In all of my foreign travels, I have never seen a higher density of this chain. There are nearly 8,000 Starbucks in China, and the number has grown fast. Not surprisingly, domestic coffee production has risen up as a competitor.

If you ask for water at a restaurant, it will be hot. Granted, I was there in the winter. But I was told this is typical year-round. It’s actually quite pleasant once you get used to it.

Restaurant meals have no “courses.” The food comes out when it’s ready, even when there are multiple dishes to be shared.

If there’s tipping at hotels, restaurants, or taxis, I didn’t see it. They assume the payment is also for the service. Gosh, that’s a better system.

Family ties are ironclad. Grandparents, children, and grandchildren all occupy the center of life — even if it means lots of travel to make it work and living situations that could strain privacy. Multi-generational households are the bedrock of social life in China.

The work ethic and ambition of young professionals is off-the-charts high. Conversations invariably included numbers of hours worked, salary targets, and promotion goals — plus an acknowledgment that there would be no short cuts to success.

I traveled through Hong Kong on my way and was surprised to learn that people need an “Entry Permit” (EEP) on their Chinese passport to enter the region from mainland China — even today, 27 years after the transfer to Chinese sovereignty.

The control of the internet is a real thing. Google, YouTube (owned by Google), most social media, and the vast majority of western news sites are blocked. There is an English-language, China-sanctioned version of CNN that is available online and on television. Interesting to observe what news is given the go-ahead.

They are enormously proud of the economic progress and poverty alleviation their country has made in the last several decades. They also expressed, at least to me, admiration for resources that our country offers. Several mentioned family members who studied or worked in the USA.

MLB in China stands for “Major League Baseball,” but not really. It’s a fashion label first and foremost. And New York Yankees and Los Angeles Dodgers logos dominate (90% of the team insignias, based on my quick tally). To the Red Sox and Giants fans out there, don’t worry — they are fans only of the logos, not the teams!

It was a fascinating trip — looking forward to going back!

(H/T to Joseph Tucker, Jonathan Li, and Kevin Zhang for helpful feedback on this post, and enormous thanks to the organizers of my trip and my medical hosts, Christoph in particular, who made it possible.)

December 12th, 2024

Dr. Thomas O’Brien — Expert in Antimicrobial Resistance and Giant in His Field (Literally)

Dr. Thomas (Tom) O’Brien was born in January 1929, in between the discovery of penicillin (September 1928) and the publication of the findings in a medical journal (May 1929). As noted by his longtime mentee Dr. John Stelling, Tom physically embodied the antibiotic era — quite appropriate for someone best known for his groundbreaking work in antimicrobial resistance. He died this week at the age of 95.

Dr. Thomas (Tom) O’Brien was born in January 1929, in between the discovery of penicillin (September 1928) and the publication of the findings in a medical journal (May 1929). As noted by his longtime mentee Dr. John Stelling, Tom physically embodied the antibiotic era — quite appropriate for someone best known for his groundbreaking work in antimicrobial resistance. He died this week at the age of 95.

A longtime faculty member here at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Tom inspired a crowd of people like me who knew him as a wonderful colleague and mentor. Regularly fielding questions about tricky drug-resistant bugs, he also radiated enthusiasm about the entire field of Infectious Diseases in a way that was never boastful or showy.

I can easily still picture his smiling face towering over the rest of us during weekly plate rounds in the microbiology laboratory, taking such pleasure in the minutiae of a surprising isolate or advance in diagnostics. “Look at this plate of VRE,” he once memorably said. “It grows better with vancomycin. How about that?”, followed by a quick chuckle of amazement at the smarts of microbes.

Tom also was the person whom I first heard describing the framework for thinking about patient care, leading to the The Four States of Clinical Medicine and the perfect two-by-two table. Just wonderful — I think about this all the time.

Here are a couple of personal anecdotes, if I may:

Way back when I was just starting out as a faculty member, still in my early 30s, I received a consultation on a patient with slow-to-resolve severe cellulitis. (Some details in the case have been changed for confidentiality.)

She had chronic leg edema, so was vulnerable to these infections, and this was the second hospitalization for this problem. She also was a high-powered professional here in Boston, a leader in her company; when I first met her, the most striking thing was the pile of impressive-looking documents and thick reports on her hospital tray table as she continued to work despite the infection.

(This was before we had laptop computers or the internet. I told you it was “way back when.”)

I introduced myself as the ID attending, and she shot me a glance over her reading glasses that could not have expressed disappointment more clearly. You? the look communicated, all but telling me, I am not optimistic that you can help me — you’re too young.

After completing the history and physical exam, I told her that the antibiotics the medical team had chosen were fine, but that sometimes these infections — which are usually caused by strep, the same or similar bacteria that cause strep throat — can take a long time to improve. Elevating the leg as much as possible could help speed the process.

Well! This was clearly not what she wanted to hear. Sighing with frustration, she told me this was unacceptable and requested a second opinion — and here’s the kicker: “… from someone older, more experienced.”

Tom O’Brien to the rescue! I saw Tom in the microbiology laboratory and explained the situation. Smiling — he was always smiling — he generously said, “Let’s go up there together and speak with her. My gray hair might reassure her.”

(He did have impressive hair. Family trait, I guess.)

To say that Tom’s kind, gentle manner helped diffuse a tense encounter barely begins to describe how calming his presence in the room was. Lowering himself down from his 6-foot, 5-inch (estimate) vantage point, and sitting by her bed, he gently gave her his thoughts in friendly, easy-to-understand terms, reinforcing what I said without in any way diminishing or ignoring her concerns. It was a master class in doctor-patient communication, and I’m grateful to this day for it.

The rest of her hospitalization she was pleasant — and patient — both with me and the slow improvement. But improve she did!

Here’s a second anecdote: My wife and I were at a divisional holiday party a year or so after the birth of our second child. Struggling big-time with two careers and two little kids, we asked Tom and his impressive wife Ruth (a corporate lawyer) how they managed — especially since they had six (!) children.

“Oh, you do your best,” he said. “Just make sure you show up for their big events. And there’s no shame in getting help.” He then proceeded to tell us that they had an account with a local cab company (this was before Uber), and that their kids happily shuttled from activity to activity using taxis while their parents were at work.

It’s not that opening an account with a cab company solved all our problems. It was his acknowledgment, in such a friendly, unpretentious way, that this parenting thing was tough but that you get by, somehow. If they could do it with six kids, certainly we could do it with two. Something about his calm and cheerful demeanor in the face of this challenge made everything seem better — an approach Tom had about many problems.

(Someone told me that he sometimes said he raised five, not six children — “the sixth one we just threw in there with the rest, and let them take care of raising number six.”)

Dr. Thomas O’Brien, you will be missed! And though I started this piece writing that he is “best known for his groundbreaking work in antimicrobial resistance,” some would argue that perhaps another fact about Tom should take that top spot. I’m speaking, of course, about his son.

Conan, my condolences to you, your mother, Ruth, and your whole family. He was a great one.

(Edit: I learned after posting this that Conan’s mother Ruth, age 92, died 3 days after her husband Tom.)

December 8th, 2024

Who’s Going to Get Lenacapavir for HIV Prevention?

At the International AIDS Conference this past summer, Dr. Linda-Gail Bekker brought down the house presenting the results of the PURPOSE 1 trial of twice-yearly injectable lenacapavir for prevention of HIV in women. The results — zero infections out of over 2000 participants — demonstrated clear superiority over oral PrEP with TDF/FTC. The study simultaneously appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine; always wonderful timing when that happens.

At the International AIDS Conference this past summer, Dr. Linda-Gail Bekker brought down the house presenting the results of the PURPOSE 1 trial of twice-yearly injectable lenacapavir for prevention of HIV in women. The results — zero infections out of over 2000 participants — demonstrated clear superiority over oral PrEP with TDF/FTC. The study simultaneously appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine; always wonderful timing when that happens.

Now, with a similar study design (without the TAF/FTC arm), we have the results of PURPOSE 2, which tested lenacapavir for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men and people who are gender diverse. Again, the injectable approach significantly beat out oral PrEP, with only two infections occurring among nearly 2000 lenacapavir recipients, around a 10-fold lower rate than in the TDF/FTC arm.

These studies highlight one of the great joys of HIV medicine, in that occasionally we get a study result that’s so dramatic it makes everyone in the field wake up and go wow. To jog your memory, here are five previous 5 wow-moments, at least in my opinion:

- Zidovudine during pregnancy markedly reduces mother-to-child transmission.

- Triple therapy with protease-inhibitor/dual NRTI-based ART improves survival — a lot.

- Integrase inhibitor–based salvage treatment gives nearly everyone a chance at viral suppression, even those with multi-drug resistance.

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis works for prevention of HIV in people at high risk for HIV.

- Suppressive HIV treatment is 100% effective for prevention of HIV transmission.

After each of these studies appeared, everything changed — and changed fast. Guideline writers scrambled to update their recommendations, and HIV treaters, clinical researchers, and community activists strongly advocated for changes to the standard of care.

Will the spectacular results of the PURPOSE 1 and 2 trials meet with the same rapid change in guidelines and rapid adoption? There are reasons to think they will, and reasons to think they won’t.

On the favorable side are, obviously, the incredibly good results — so good that many media reports incorrectly cited these twice-yearly injections as a “vaccine”. Hey, quick fact check, it’s not a vaccine!

(Though parenthetically, one does speculate that something this effective will make HIV vaccine research even harder than it is already. How can one demonstrate better protection with a vaccine than seen in the PURPOSE studies?)

The contrarians will cite the current high cost of lenacapavir as treatment, especially compared to generic TDF/FTC, which CostPlus drugs now lists at $32 for a 3-month supply, and many government-sponsored programs will pay for entirely.

Plus, we have the cabotegravir experience in the “real world”, a sobering reminder that efficacy does not equal effectiveness — or at least not if the breakthrough treatment isn’t put into practice. Remember, cabotegravir was also significantly more effective than TDF/FTC in two blinded clinical trials, demonstrated 100% efficacy in women (if one excludes the participants with HIV at baseline), and has been FDA approved for HIV prevention since December 2021.

And our use of cabotegravir so far in the USA? Based on a recently published CDC report of national prescription trends for PrEP, it was around 3% of those on PrEP in 2023; someone who works on PrEP implementation research told me that it’s only a bit higher today. And its adoption in the parts of the world with the highest HIV incidence is, sadly, essentially zero.

FDA approval of lenacapavir for PrEP is pretty much a sure thing, and expected some time in 2025. Who will get it for HIV prevention promises to be one of the more fascinating stories in HIV medicine over the next couple of years. Stay tuned.

November 27th, 2024

Some ID Things to Be Grateful for This Holiday Season — 2024 Edition

Not a fan.

The calendar says it’s nearly the fourth Thursday of November, so here in the United States, the Thanksgiving holiday is upon us. It’s a day when we gather with family and friends to express thanks, to eat plenty (usually too much), to watch a bunch of spectacular athletes bash themselves to smithereens in the name of sport, and to wonder why anyone would eat sweet potatoes with marshmallows.

(Must be the same people who eat candy corn during Halloween. Yuck on both accounts. And no, I cannot be convinced otherwise.)

It’s also time for me to take stock of our ID world, citing some things in our field that I’m grateful for — an annual tradition on this site. Off we go:

Twice-yearly lenacapavir was really effective for HIV prevention. How could this not garner first mention? While it awaits FDA approval for this indication, and making it broadly available will be a critically important challenge, this should a major advance in pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV.

We’re about to get a bunch of new drugs for treatment of urinary tract infections. The FDA already approved sulopenem etzadroxil with probenecid and pivmecillinam, and they granted gepotidacin priority review (approval expected by March, 2025). Since UTIs are increasingly caused by resistant organisms, I count this as progress. Naysayers will say, “But what about resistance, side effects, cost, and access?”, so allow me to cite the ID doc’s consistent ambivalence about new antimicrobial agents.

But since this is a gratitude post, I’ll just go with the glass half full here — and hope I can figure out how to say sulopenem etzadroxil with probenecid without using the trade name (it might be impossible).

Three additional studies confirmed the remarkably high resistance barriers of dolutegravir and bictegravir. The results of D2EFT (pronounced “DEFT”), VISEND, and a study from the GHESKIO treatment center in Haiti all gave the same message — that these two integrase inhibitors could be used with tenofovir/3TC or FTC and still achieve or maintain viral suppression, regardless of the degree of baseline NRTI resistance. Amazing! Great to have confirmatory data in support of the prior NADIA and 2SD studies.

Seven days of antibiotics was noninferior to fourteen days in the treatment of bloodstream infections. What a great clinical trial — ask an important and common clinical question, set up the primary and secondary endpoints to be of substantial interest, and then power it appropriately to answer the question. The results provide some solid evidence for The Rules, at least if Staph aureus and endocarditis aren’t in the picture. Why can’t we have more clinical trials like this? Can’t wait to hear what they find in secondary analyses, and in their follow-up BALANCE+ studies.

Metagenomic sequencing and other advanced molecular techniques are slowly making their way into clinical practice. I’d bet good money that if I asked 100 practicing ID docs whether they’ve had at least one case where one of these tests provided a solid, practice-changing diagnosis — rapidly and without an invasive procedure — more than 90% would raise their hand. Maybe 99%.

Rwanda appears to have contained the Marburg virus outbreak. In doing so, the country provided a model for pathogen response, involving enhanced testing, rapid initiation of isolation policies, and scaling up supportive care. If there are no further cases by December 21, the outbreak will be declared over.

The DHHS HIV treatment guidelines removed abacavir from its list of recommended initial treatment regimens. If you combine abacavir’s deficiencies (hypersensitivity, cardiovascular risk, lack of hepatitis B activity, pill size) with the remarkably high effectiveness of dolutegravir/lamivudine and the renal and bone safety of tenofovir alafenamide, there’s hardly any reason to use abacavir anymore — you really have to do some mental acrobatics to come up with a compelling indication. Nonetheless, I suspect HLA-B*5701 will live rent-free in our brains forever.

Non-ID gratitude section:

eBikes are now widely available, in many different styles and at a broad range of price points*. If you haven’t tried one yet, what are you waiting for? They are miraculous machines, allowing you to ride unthinkable distances and zoom up steep hills, so therefore can replace cars on many routes. I already have over a thousand miles on mine and have had it only around a year. (*What’s the difference between a “price” and a “price point”. Gosh if I know.)

Andrea Petkovic is a very fine writer. Two things I’m obsessed about are tennis and great writing. How exciting it’s been, therefore, to discover a professional tennis player (now retired) who provides both? Her writing alternates topics breezy and serious, the tone is deft, human, and humorous, and every week there’s a new selection — the most recent example a beautiful rumination on the retirement of Rafael Nadal. The strength of self-published newsletters comes to life in examples like this.

I discovered at least one thing that Microsoft Teams does better than Zoom. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it’s sharing a Powerpoint presentation. Here’s the brief summary: if you share the file rather than sharing your screen, it gives you a great look at your upcoming slides and other features. It’s the “Presenter View” without having to do anything. Transformative!

Jim Gaffigan is skinny now, and even better, he has a new comedy special. He naturally starts out by explaining how he got his new sleeker physique (this will be no surprise), and the responses he’s received from others — all A+ comedy material from this brilliant and prolific comedian. But he quickly veers off into much broader territory, in particular parenting (he has 5 kids) and, in one particularly funny bit, technology.

Take it away, Jim!

Hey, I’ve been doing this post for years now and expect that I’ve missed one of your favorites. What are you grateful for this year?

November 18th, 2024

Marking a Social Media Mass Migration — Until the Next One

Periodically my wife and I will have a bunch of trainees (medical students, or residents, or ID fellows, or a mix) over to dinner. Seated around a big table, with no time-crunch of rounds, pagers, or EPIC orders, we can all get to know one another in this more relaxed setting.

Periodically my wife and I will have a bunch of trainees (medical students, or residents, or ID fellows, or a mix) over to dinner. Seated around a big table, with no time-crunch of rounds, pagers, or EPIC orders, we can all get to know one another in this more relaxed setting.

Plus, they get free food, never a bad thing in the years before you start having a real salary.

It helps at these events to have a few icebreaker questions ready in case the guests are nervous, or just because the answers to the questions are so darn interesting. One of our favorites is the classic, What do you love to hate, and hate to love?

To clarify the question, for the purposes of this post, love to hate means something you feel with such a passion that you’ll go on and on about how much you hate it. For years, my answer was readily at hand — football, the American version. I bore people at social events on this topic, despite being in the minority, and once even wrote an opinion piece making my argument.

But for the past 2 years, my response has changed. The thing I now love to hate is what a certain billionaire has done with the site formerly known as Twitter.

(Sorry, I can’t refer to it by the new name. That name is so unimaginative, so eye-rollingly juvenile that it hurts even to write it. Truly.)

As I’ve noted before, the appeal of the original Twitter snuck up on me, with my participation essentially zero for years after I signed up. Then I discovered it was the easiest way to keep up on the latest advances in our field — infectious diseases specifically and medicine in general.

During the pandemic, it became all but indispensable, as changes to the best treatment and prevention strategies came so quickly that I felt I had no way of staying current without it. Experts from around the world — people I otherwise never would have known about or met — enhanced its value, weighing in on strengths and weaknesses of new studies.

I supplemented this informational use of Twitter with several other useful tasks. I could boost the accomplishments of others, promote my own work, and (no small thing) indulge in several miscellaneous hobbies (baseball, tennis, cute dog videos).

The fact that I’d figured out a way to tweak the settings so that attackers couldn’t view or respond to my posts — and strictly followed Peter Sagal’s rules — made some of the more widely publicized limitations of Twitter something I was able to avoid. It was like having an effective social media vaccine.

So what happened? Since October 2022 — note date — my experience on the site has steadily deteriorated. The effectiveness of that vaccine has faded. So what happened?

- Curation now fails. The algorithm either stinks, or most of the people in my field stopped posting interesting things, or both — hence I’m rarely seeing good ID content. Lots of what I get in my feed is irrelevant junk. Pointless ads. Spam.

- Limits on the blocking function. Why on earth would they remove this key safety feature?

- Limits on displaying graphics generated from certain URLs, or limits on those URLs entirely. Surprise, surprise, they might be competitors, or sites that someone (guess who) doesn’t like.

- A certain person’s posts pop up repeatedly, even though I don’t follow him. Hint: He owns the place.

- Bots. Who’s real and who isn’t? Very hard to tell.

- Payment is regularly requested to boost influence. Wasn’t “flattening hierarchies” one of the proposed benefits of Twitter, our “digital town hall”?

- The stupid new name. See above.

That’s plenty. Thanks to the prescient departure from Twitter of my colleague Dr. John Ross years ago, and the energetic assembly of ID “starter packs” by Dr. Ilan Schwartz, I’m joining hundreds of ID docs and millions of others who went over to Bluesky in the past couple of weeks — here I am. That’s a new background photo of Louie, featuring one of the silly plates my wife discovered in a remainder bin.

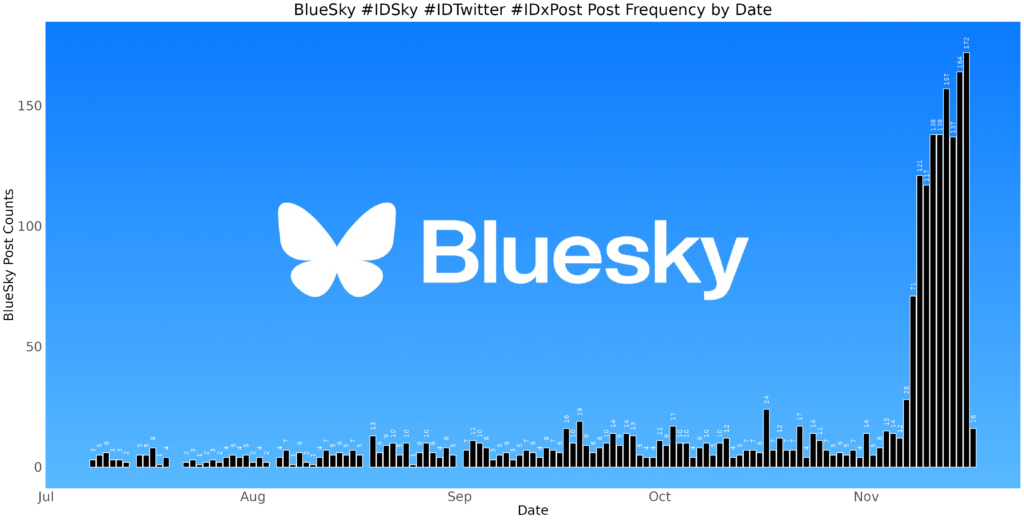

And wow, this has been a fast switchover, nicely documented both by the mainstream media and more specifically for us ID docs, by Dr. Ken Koon Wong. (That’s his figure on ID engagement at the top of this post, used with his permission.) If you’ve been active as a poster or just lurker on Twitter, I’d encourage you to give Bluesky a try. Here’s Ken’s excellent guide on how to get started.

Let’s see what happens over time. I have no illusions about the permanence of this move, as nicely articulated in a recent piece in The Atlantic. Ignored or abandoned social media sites (MySpace, Friendster, Mastodon, et al.) lay at the bottom of digital scrap heaps like unused USB drives in your desk drawer from a decade ago. Plus, I have no idea how the owners of Bluesky will find a way to support it financially.

Note that the above list of reasons to leave Twitter left off its political associations. Honestly, that is the one thing that I’ll probably miss the most about leaving the site — the exposure to perspectives different from my own. Bluesky has already been accused of being an “echo chamber,” a notorious limitation of social media in general, most notoriously Facebook — of course your “friends” agree with most of your views!

Other limitations of Bluesky are more technical than systemic. You can’t easily bookmark posts. There’s no app optimized for tablets. No polling function. Their servers sometimes struggle with the massive influx of new users. And I have no idea how they plan to make money on this thing, which ultimately I guess will determine its longevity.

Importantly, I haven’t found most of the cute dog feeds yet. But I’m hopeful since WeRateDogs has made the move!

This is Lily. She's been accused of drinking her mom's slushie. Will not be taking any questions at this time. 14/10

I trust you, Lily.

So this is where I’ll be in the social media universe, at least for the time being. Looking forward to more of that great learning I had from Twitter in the pre-2022 era — Bluesky can’t be far off if Dr. Tony Breu has already posted.

And if you’re wondering what I hate to love (the other part of the two-part question), it’s potato chips. Irresistible, but not salubrious.

And it looks like I’m not the only one.

Today in relatable science: Gulls making a mysterious daily trip that turned out to be to a potato chip factory

— Brooke Jarvis (@brookejarvis.bsky.social) 2024-11-15T20:15:15.323Z

November 12th, 2024

Musings About a Bruising and an ID Link-o-Rama

An ID Link-o-Rama — get it?

We’ll get to the ID links in a moment, but first, allow me to share a few words about the election, which strangely feels like a million years ago.

(It was a week. Time is strange.)

Instead of rehashing what happened and what’s to come, here’s what I’m offering: some feelings from one specialist in infectious diseases — me.

I’ll start by saying that long-time readers can probably surmise that the winner on November 5 wasn’t the candidate I voted for. I know, shocking.

Nor would you be surprised to hear that most of my ID colleagues voted the same way I did. Not all of them, of course — our political leanings may tilt heavily one way, but they’re not unanimous.

Still, as the results of the election rolled in and it became evident that they would yield an incontestable win for the Red Team, it occurred to me (as it did in 2016) that our pervasive opinion puts us outside the norm. That’s usually okay — why be mainstream all the time? I think we ID doctors wear our distinctiveness with pride, if not with fancy clothes.

But the post-election feeling among most of my colleagues (and me) was one of disbelief — how could someone vote for that guy? It also made me feel isolated, and sad.

This is especially the case since this country of ours happens to be one that I have deep affection for, warts and all.

Truth be told, even with the election of a man who claimed that recent immigrants are eating dogs and cats, and who once suggested that injecting a disinfectant would treat a novel coronavirus, there’s no place else I’d rather live. Here’s one big reason why: It’s that I have the freedom — the right — to voice a critical opinion of our president-elect, and that I proudly voted with the 72 million and not the 75 million voters. Let’s not take that freedom for granted, and continue to defend it.

On to the ID links, a baker’s dozen to prepare us for Thanksgiving pies, just a bit over 2 weeks from now.

Ensitrelvir prevented the development of symptomatic COVID-19 among household contacts. These are potentially exciting results, especially since Paxlovid did not work in a similar prevention study, and whatever monoclonal antibody du jour we’re using seems doomed to fail eventually as variants emerge. Ensitrelvir is a SARS-CoV-2 protease inhibitor approved for use in Japan and Singapore; I’m very hopeful we’ll have access to it here as well.

7% (8 out of 115) of dairy workers had serologic evidence of highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1). That seems like a lot, doesn’t it? Whether H5N1 will eventually yield an increase in influenza case numbers and/or per-case severity during this or future flu seasons remains unknown, but most definitely deserves close watching.

A large collaborative group of ID pharmacists and doctors published WikiGuidelines for prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections. What a sensational resource of data on diagnosis, treatment, and prevention! Really great. But somewhere along the way I lost the meaning of the term “Wiki” as it applies to mega-projects like this — what does it mean?

Once again, macrolide resistance was strongly predictive of poor outcomes in pulmonary disease due to M. avium complex. Those with MICs ≥32 µg/mL had an odds ratio of 0.25 for achieving microbiological cure.

Omadacycline treatment of M. abscessus led to a faster resolution of symptoms and better microbiologic clearance than placebo. It’s a small, phase 2 study, but it would be huge if eventually omadacycline gets FDA approval for this difficult-to-treat infection.

Related, here is a “State-of-the-Art” review of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. Written by top experts in the field, it covers all the main topics in a practical, informative way. Highly recommended, as I do all the State-of-the-Art Reviews in Clinical Infectious Diseases!

Cases of pneumonia due to mycoplasma have increased substantially in children and young adults. I first heard of this through my most reliable (and readily available!) source of community infectious outbreaks — my primary care pediatrician wife, who says recently “everyone” seems to have it. Helpful clues (per her) are failure to respond to beta-lactams and those weird mycoplasma-related rashes.

Immunity following yellow fever vaccination appears to be durable. Breakthrough cases occur but very rarely. This paper supports the recommendation that a one-time shot for travelers need not be repeated, so very good news.

In its first year of availability, the RSV vaccine reduced the risk of hospitalization by 80% among adults over 60. It was also effective in immunocompromised hosts. It remains unclear whether these vaccines will need to be repeated; for now. there is no recommendation to do so.

According to this preprint study, by the end of 2023, 99.9% of the U.S. population had immunologic exposure to SARS-CoV-2 via either infection or vaccination or both. Previous infection was also nearly universal, at 99.4%. It’s in this immunologic milieu that current antivirals for COVID-19 must make their impact — a tall order, but I believe still achievable with appropriate symptom-based endpoints.

In data collected from two academic medical centers over 5 years, uptake of anal cancer screening for men who have sex with men who have HIV was very poor. Additionally, cytology performed badly in both sensitivity and specificity, raising questions about whether we should be doing it all (versus referring high-risk individuals directly for high-resolution anoscopy). Am I the only one who thinks that the guidelines issued for anal cancer screening are impractical to implement and not evidenced-based?

Using a hospital-based database, investigators found that 41% of patients with babesiosis had coinfection with Borrelia burgdorferi, the etiologic agent of Lyme disease. I knew it was high, but didn’t think it would be that high — should probably prompt empiric doxycycline in everyone newly diagnosed with babesia. Wow. By contrast, ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis occurred in only 3.7% and 0.3%.

There is very little good evidence on the optimal use of long-term suppressive antibiotics therapy, prompting this sensible review. The four main categories they cover are prosthetic joint infections, hardware infections of bone not involving joints, vascular graft infections, and cardiac implantable electronic devices. The authors also offer advice about monitoring and situations to consider antibiotic cessation.

Ok, now a few bonus non-ID links — just one involving politics, I promise!

The New Yorker just reposted Claire Keegan’s exquisite short story “Foster”. It was later published as a novella, and made into a movie called The Quiet Girl. Some think the book is better than the movie, others the reverse. Regardless, I can’t recommend either of them strongly enough. The movie for another great book of hers, Small Things Like These, has just been released. Anyone see it yet?

For a laugh-out-loud read that will resonate strongly with those charged with writing letters of recommendation, give Dear Committee Members by Julie Schumacher a try. Giving new meaning to the term epistolary novel, the book captures the life of a middle-aged academic who’s clearly past his prime, but still has quite the way with words. I heard about this book from my friend (name dropping, sorry) Andy Borowitz, so thank you, Andy!

Speaking of, Andy Borowitz thinks the President-elect is in for a world of trouble. Love this quote: “As for Trump’s war on inflation, the skyrocketing prices caused by his proposed tariffs will make Americans nostalgic for pandemic-era price-gouging on Charmin.”

The online piano instructional company Pianote has some astounding videos on YouTube. The most remarkable are those where they play a song for the first time to a gifted musician, to see what they can do with it on the spot. See the video below for a remarkable example.

Makes a person optimistic about the capabilities of the human species, doesn’t it?

October 30th, 2024

The Riveting Conclusion of How PCP Became PJP

Before I get back to the saga of Brave New Name — How PCP Became PJP and Why It Matters, allow me to share that I had some trepidation about publishing this thing.

A deep dive down a hole with very high-risk for tularemia exposure (see what I did there?), it veered off topic more than half-baked Tesla Robotaxi loses the roadway during a driving snowstorm. Worried, I tested a draft of Part 1 out on a regular reader I trusted very much. (Ok, ok, my Mom.) She confessed she was “skimming by the end”, which made me concerned I’d gone too far.

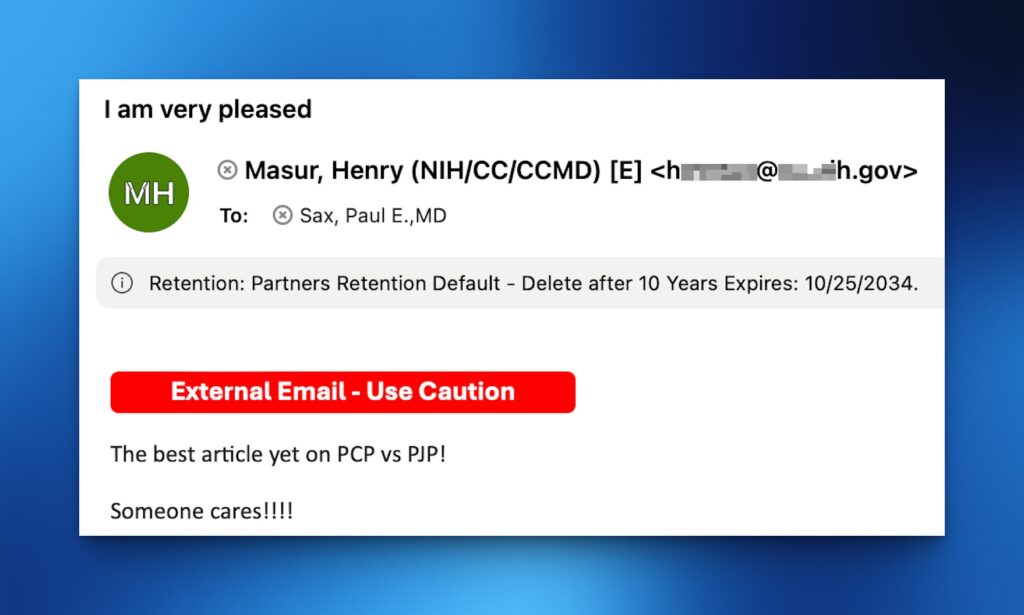

But when I got this after posting Part 1, I knew the piece had hit its target:

Kind email from Henry, shared with his permission.

Dr. Henry Masur! The Pneumocystis Expert Extraordinaire is “very pleased”! Amazing!

Now, back to our story.

(Read this next sentence like a voiceover starting the next episode in your favorite series … )

Previously, on Brave New Name — How PCP Became PJP and Why It Matters, we learned that the cause of the most famous HIV-related opportunistic infection — Pneumocystis carinii — was actually a rat fungus, and not a human pathogen after all. The name Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, and its abbreviation PCP, were both in jeopardy.

If we take the perspective of the scientists making the discoveries about the genetic basis of the organism, this was not a time for sentimentality — it was a time for facts. Pneumocystis carinii was not the bug infecting humans, and that error deserved correction.

To solve this problem, a group of motivated researchers gathered in 1999 at a meeting to settle the issue once and for all. (That meeting must have been a banger.) In a bold move strongly supported by the molecular evidence, they renamed the human pneumocystis Pneumocystis jiroveci (more details here without a paywall) in honor of the the Czech parasitologist Dr. Otto Jirovec who first described the infection in humans.

(Ostensibly the first. Read on.)

Shock waves resonated through the ID and microbiology community. I remember walking down the street in Back Bay, Boston, one July evening in 1999, enjoying some warm summer breezes, and suddenly I heard a loud screams in the distance. What had happened?

Pedro Martinez had struck out 5 of the 6 betters he faced in baseball’s All Star game at Fenway Park. It had nothing to do with this Pneumocystis name change. Still, this novel last name (jiroveci?) of human Pneumocystis caused an multifactorial crisis of international proportions. Among the problems, here are a quick half-dozen:

1. No one knew how to pronounce it. This confusion continues today.

Hey Julien! Thanks for taking the time to make this video. Good try (and lovely music!), but a brief search would have yielded the correct pronunciation, which is “yee row vet zee”. Say it again with me — yee row VET zee.

Of course now that you’ve learned it, we’ll share that some think it should be “VET-chee”, not “VET zee”. But this is hardly the only issue.

2. The original spelling ended with one “i,” when in fact it should be two — jirovecii, not jiroveci. The error arose out of a conflict between standards set by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (one “i” for a parasite) versus the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (two “i’s” for a fungus). And yes, someone published a letter on this topic. (Wow, talk about padding your CV.)

Now say it again with me — yee row VET zee aye. Or, if you prefer, yee row VET chee aye.

Brief aside: (Editor: Yeah sure.) How many International Codes of Nomenclature are there? Where do the committees making the decisions meet? Do they get swag (water bottles, T-shirts, fleeces) at their meetings? If so, I’d like someone to send me a backpack with an “International Code of Canine Nomenclature” logo, which I’m sure has a cute pup on it. Thank you.

3. Not everyone agreed the name should be changed. Dr. Walter T. Hughes (remember him? he’s the “Famed Pneumocystis Guru” from Part 1, the guy with the Cushingoid rats) strongly opposed the change, stating that good old Otto Jirovec was not even the first person to discover the pathogen in humans — that credit should go to Drs. Meer and Brug, with a paper they published a full decade before Jirovec, who must have stolen a page from Carini’s book to claim he was the first.

More importantly, “changing the name to Pneumocystis jiroveci [sic] will create confusion in clinical medicine where the name Pneumocystis carinii has served physicians and microbiologists well for over half a century.” So wrote Dr. Hughes, who no doubt would be surprised that we post here a picture of him as a 3-year-old on his family farm in Ohio.

Dr. Walter T. Hughes, 1933 — although he wasn’t a doctor quite yet.

4. Other joined in the battle to save carinii. A certain Dr. Francis Gigliotti later took up the fight with his own impassioned plea — one where he saw the name change as an unfortunate first step in a chaotic world of new and confusing names for Pneumocystis, each derived from their species-specific origins:

Because the overwhelming majority of “species” are currently “undiscovered” at this point, anyone can submit a new species name for any of the Pneumocystis organisms that infect each mammalian host that has not yet been specifically named. If individuals choose such an approach, what effect will this have on the desire to have an organized system to name Pneumocystis derived from monkeys, chimps, rabbits, dogs, horses, cows, or goats, for example?

What effect indeed! Imagine our frustration as we cared for immunosuppressed goats with pneumonia, desperately trying to remember the goat-specific name.

A baby goat, otherwise known as a kid. Male kids are bucklings, female kids doelings. Aren’t you glad you read this blog?

Instead of rashly changing Pneumocystis carinii to Pneumocystis jirovecii, Gigliotti proposed setting up a task force headed by an impartial scientific body, such as the National Institutes of Health. Another meeting! And such a fine use of our taxpayer dollars, to address this important issue!

5. Despite these protests, advocates for the name change would not back down. Drs. Melanie Cushion and James Stringer (he wrote the spelling-change letter) swiftly countered Drs. Hughes and Gigliotti, defending the name change with strong words of their own: “Dr. Gigliotti’s argument against species recognition was stretched beyond reasonableness when it included a defense of practices inconsistent with sound microbiology.” Them’s fighting words!

And if you doubt the authors’ credentials, Dr. Cushion and Dr. Peter Walzer wrote a whole book about Pneumocystis. Entitled Pneumocystis Pneumonia, it’s now in its 3rd Edition. Here’s one Amazon Review:

Big words about a small bug

I was scrolling through the internet, looking for some light reading, and came across this substantial tome — 2.42 pounds, no less! The title drew me in. I was a big fan of Pneumocystis Pneumonia, 2nd Edition, by the same authors, and was looking forward to the next revision. I was not disappointed. Drs. Walzer and Cushion have a breezy style that others might tend to dismiss as not up to the serious task of fully conveying the scientific importance of Pneumocystis pneumonia. But I think they strike just the right tone. I can’t wait for Pneumocystis Pneumonia, 4th Edition.

(I made that review up. Sort of. Modified with permission from the original author.)

To be fair, Pneumocystis Pneumonia, 3rd Edition, is not cheap (list price $170). But at over 700 pages long, the book arguably is excellent value. I have a copy on my coffee table.

6. If the name is to be changed — and, much to Dr. Hughes’s and Gigliotti’s dismay, it ultimately has changed — what should the abbreviation be? We arrive back, finally, to the topic of these two posts — you thought I’d never get there, didn’t you?

Even after Pneumocystis jirovecii’s widespread adoption, some wanted so badly to stick with PCP over PJP that they dug up a “c” in the middle of the new name that they could recycle: PneumoCystis jirovecii pneumonia. Clever!

Indeed, several change-the-name-to-jirovecii advocates, backed by the legendary Dr. Ann Wakefield (of Pneumocystis wakefieldiae fame), even embraced this compromise. Tossing a bone to the Pneumocystis carinii supporters, she wrote this reassuring sentence in the abstract of a paper, undoubtedly to assuage the complaints they probably didn’t anticipate would become so passionate.

Changing the organism’s name does not preclude the use of the acronym PCP because it can be read “Pneumocystis pneumonia.”

My friend Dr. Joel Gallant has always loved this solution, a way of harkening back to happier and more innocent times when Aggregatibacter aphrophilus was the much more mellifluous Haemophilus aphrophilus. As a result, for many years one of the chapters on Pneumocystis pneumonia I wrote in UpToDate included this sentence:

The abbreviation of “PCP” is still used in the infectious disease community to refer to the clinical entity of “PneumoCystis Pneumonia”; this allows for the retention of the familiar acronym amongst clinicians and maintains the accuracy of this abbreviation in older published papers.

Well, PCP would no longer technically be an acronym — it’s not the first letters of other words, the definition of an acronym — but it seemed like a reasonable compromise. Now everyone can be happy, right?

The Big Conclusion

Well, not happy for long. Time marches on, and with it the generation of doctors and nurses and pharmacists who clung to Pneumocystis carinii and PCP have gradually been outnumbered. Younger clinicians, less-biased by these historical squabbles and unaware of the gymnastics required to keep the abbreviation PCP relevant, simply don’t care. They see something called Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and turn to the most immediately obvious shortcut — PJP.

In other words, younger age is an independent predictor of use of PJP over PCP. I base this on a multivariable analysis the NEJM Journal Watch statistical editor did on the responses to my original poll, using the demographic information each participant provided. Although such an data review never occurred — no one submitted demographic information, and there was no multivariable analysis — it sounded so impressive to write that, I couldn’t resist. Nonetheless, the first sentence of this paragraph is still true. Younger folks pretty much all say PJP.

And in order to stay youthful, that’s what I call it now too. Look, here’s proof!

Have a great Halloween, everyone! And thanks for sticking around to the end.