An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

April 30th, 2025

On-Service ID Link-o-Rama — Osmosis Edition

First-year ID fellows this time of year bring a lot to inpatient consult rotations. Years of high-volume inpatient care have sharpened their clinical instincts, and at this point they have an impressive fund of ID knowledge. Plus, the fellow on our current rotation gets along great with everyone — patients and consulting clinicians alike — a remarkable and under-appreciated talent that really brings joy to the experience of being on the “ID Team.”

First-year ID fellows this time of year bring a lot to inpatient consult rotations. Years of high-volume inpatient care have sharpened their clinical instincts, and at this point they have an impressive fund of ID knowledge. Plus, the fellow on our current rotation gets along great with everyone — patients and consulting clinicians alike — a remarkable and under-appreciated talent that really brings joy to the experience of being on the “ID Team.”

What ID fellows emphatically don’t have, however, is lots of free time — hence non-medical, non-ID things appropriately take priority in what little free time they have. That laundry isn’t going to wash, dry, and fold itself. You wish.

Because first-year fellows are so busy, I tell them they’ll get emails from me pretty much each day with at least one relevant study, something I’ve very briefly cited on rounds. Here’s the important part: I also tell them they do not need to respond, or even to read the referenced paper. It’s for subconscious learning, a kind of literature osmosis — something I’m sending in their general direction now that might seep into their brains for the future.

So here’s a bunch of them from this rotation, with some bare-bones commentary.

The Best Way to Rule Out Active TB. In head-to-head comparisons, Xpert MTB/RIF outperformed AFB smear in ruling out pulmonary TB — useful both in low- and high-prevalence settings. Two negative tests in the U.S. had a 100% negative predictive value for active TB. The amount of energy, time, and money spent — some might say wasted — ruling out TB in low-likelihood cases here never ceases to astound me; on the other hand, cases of unrecognized TB can be disastrous both clinically and from a cost perspective. Still, in low-risk patients, it’s the infection control version of everyone being forced to take off shoes before going through security at the airport.

Drug Hypersensitivity to Antibiotics That Aren’t Beta-Lactams. Fluoroquinolones, vancomycin, tetracyclines, and macrolides all can rarely trigger immediate (type 1) hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs). It can be particularly tricky with severe vancomycin infusion reactions, as these can mimic type I HSRs with angioedema, chest pain, dyspnea, bronchospasm, and hypotension. Mast cells doing their mast cell thing.

Inhaled Amikacin for Refractory Pulmonary Mycobacterium avium Complex (MAC). This pivotal trial led to FDA approval of inhaled liposomal amikacin for pulmonary MAC, showing a higher culture conversion rate for amikacin (29%) compared to standard therapy alone (9%). A high proportion of participants got side effects like hoarseness and bronchospasm, so be prepared if you use it. I highlight the study here because it’s one of the rare controlled clinical trials in this very common condition, a glaring data gap we feel just about every day in ID practice. As a result, nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) pulmonary disease remains fertile ground for anecdotes and strong opinions — more good studies would be welcome!

CMV Reactivation in the ICU: Treat or Don’t Treat? Short answer for immunocompetent patients: don’t treat. This randomized clinical trial was stopped early due to worse outcomes with valganciclovir. It’s still unknown what to do in immunocompromised patients.

Myasthenia Gravis and Antibiotics: Caution with Fluoroquinolones and Macrolides. Prior to this rotation, I had thought that only aminoglycosides exacerbated this condition, but it turns out other drug classes can do the same. A fund-of-knowledge lacune for me. Credit to my current fellow who taught me this, so here’s to the bidirectional flow of knowledge that happens every rotation! Yay!

Crushing BIC/FTC/TAF for HIV Treatment. Good news: Based on this study presented at CROI 2025 by some of my brilliant ID pharmacist colleagues, crushing bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide for tube feeds seems feasible for patients unable to swallow whole tablets. And for those who don’t do HIV medicine on the inpatient service, trust me — this comes up a lot.

In HIV, Hospitalization for Acute Infections Markedly Lowers CD4 Cell Counts. While the linked study looked only at pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in people with HIV not on ART, this phenomenon also happens with suppressive ART — which can be very scary to those not in the know. However, the CD4/CD8 ratio is not influenced, and counts will recover when the illness resolves.

How Long to Treat Spinal Osteomyelitis? An exception to the “shorter is better” rule, this observational trial suggests 6 weeks isn’t always enough. Longer therapy for high-risk cases (especially due to MRSA) may be warranted; I find CRP monitoring helpful in these cases. Importantly, oral rather than IV therapy makes this a much more viable strategy.

That last one is a good transition to a designated Staph aureus section, in honor of the first-year ID fellow’s primary nemesis:

Cefazolin and Ertapenem for Persistent MSSA Bacteremia. It’s hard to believe that patients can have days or even weeks of positive blood cultures despite appropriate antibiotics with this nasty bug, but it’s a common enough consult for ID doctors that we see this repeatedly. This case series reported rapid clearance with the combination of cefazolin plus ertapenem, the two antibiotics targeting different penicillin-binding proteins. Bonus: They included an animal endocarditis model showing lower vegetation bacterial counts with combination therapy.

Does PET/CT Actually Improve Mortality in Staph aureus Bacteremia? Maybe not. This clever analysis highlighted “immortal time bias” — patients need to survive long enough to get the scan, making survival look artificially better than those who don’t get the scan. Once adjusted for this bias, PET/CT was no longer associated with improved outcomes. By the way, both the combination ertapenem and cefazolin treatment and this PET/CT issue are part of the SNAP trial. Amazing!

Cefazolin for CNS Infections due to Staph aureus — the Debate Continues. Probably it’s ok, as pharmacokinetic data suggest it may provide even better drug levels than nafcillin and oxacillin, and clinical failures with breakthrough infection are rare. But not everyone is convinced. Certainly will be interested to see what the SNAP trial teaches us with this population. (H/T to Dr. Jonathan Blum for these references.)

Quantitative Microbial Cell-Free DNA Sequencing from Plasma Can Help Diagnose Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Infections. Not everyone with implantable cardiac devices and staph bacteremia has device infection. In this study, patients with definite infection had DNA levels (as measured by the Karius assay) that persisted during antibiotic therapy, spiked after device extraction, then declined rapidly. Conversely, in patients with only possible infection, levels became undetectable after several days of antibiotics and remained so post-extraction. The test could one day become a standard part of monitoring these patients, though today such a strategy would be prohibitively expensive.

So that’s a wrap — a bunch of papers sent with zero expectation they’d be read immediately by the fellow on our ID team, even though she’s outstanding! But maybe one or two will seep in via osmosis — or (to switch metaphors mid-sentence), stick like that song you heard once, and now know forever.

April 18th, 2025

SNAP Trial Helps Resolve Long-Running Controversies Over Management of Staph Bacteremia

For those who do hospital-based patient care, the significance of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) cannot be overstated. It’s one of the most frequent reasons for infectious disease consultations — and for good reason: when mismanaged or complicated, it can lead to high morbidity, a myriad of complications, and a disturbingly high mortality rate.

For those who do hospital-based patient care, the significance of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) cannot be overstated. It’s one of the most frequent reasons for infectious disease consultations — and for good reason: when mismanaged or complicated, it can lead to high morbidity, a myriad of complications, and a disturbingly high mortality rate.

Despite its clinical importance, pivotal questions about optimal management have lingered for decades — stuff we were talking about during my ID fellowship remain unresolved, and that’s saying something. This uncertainty stems partly from the remarkable heterogeneity of the illness, with cases ranging from straightforward and swiftly resolved to fulminant sepsis with multiple metastatic complications despite appropriate antibiotic therapy. Persistent bacteremia — defined as continued blood culture positivity after initiating treatment — is disproportionately associated with S. aureus, outnumbering other pathogens by orders of magnitude.

One long-standing debate centers on the optimal antibiotic for MSSA bacteremia — after all, a bunch of drugs are active in the laboratory against staph. Does the better safety profile of cefazolin outweigh the theoretically superior in vitro activity of anti-staphylococcal penicillins (nafcillin, oxacillin, flucloxacillin) in the setting of high bacterial burden — the so-called “inoculum effect”? Another unresolved issue is whether we can trust penicillin susceptibility testing when the lab reports an MSSA isolate is penicillin sensitive. In the lab it looks great, but is old-fashioned penicillin really still a viable option?

Enter the SNAP (Staphylococcus aureus Network Adaptive Platform) trial — the largest randomized controlled trial ever conducted for SAB. Led by Drs. Joshua Davis and Steven Tong from Australia, this global study encompasses sites across Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Canada, Israel, South Africa, Europe, and the U.K.

(Conspicuously missing: the United States. Sadly, this isn’t because we’ve eradicated S. aureus or because “if you are healthy, it’s almost impossible for you to be killed by an infectious disease,” as a certain high ranking health official confidently — and wrongly — claimed. It’s estimated we have 120,000 episodes of SAB per year with 20,000 deaths. No, the real reasons are the diverse challenges to doing collaborative clinical research in our country, a deficit deserving of a separate post. Sigh.)

The SNAP trial is an adaptive clinical trial, evaluating a broad range of interventions with the goal of improving outcomes for this life-threatening condition. At ESCMID Global 2025, we got our first look at some SNAP results — and they were worth the wait. Two key comparisons were presented: cefazolin versus flucloxacillin for MSSA, and penicillin versus flucloxacillin for penicillin-susceptible S. aureus (PSSA). The MSSA trial enrolled 1341 participants; the PSSA one, 281. For those wondering about flucloxacillin (which is not available in this country), data from this same research group suggest it is quite similar to both nafcillin and oxacillin.

Highlights from the cefazolin study:

- Cefazolin was noninferior to flucloxacillin for 90-day mortality in MSSA bacteremia — 15.0% and 17.0%, respectively.

- Acute kidney injury rates were lower in the cefazolin group.

- Early mortality was lower with cefazolin.

Highlights from the penicillin study:

- Penicillin was noninferior to flucloxacillin in 90-day mortality (13.8% vs 21.5%, respectively) — and might have been superior with a larger sample size.

- Significantly lower rates of acute kidney injury with penicillin.

- If your lab is conducting penicillin susceptibility testing for S. aureus correctly, you can trust the results — penicillin is fully active.

It’s always a thrill when clinical research sets out to answer important questions directly related to patient care, and these two first SNAP trial results clearly succeeded. Anyone doubting whether cefazolin should be first line over a semi-synthetic penicillin — data suggested in observational studies — can remove those concerns; similarly, penicillin is clearly the better choice for susceptible strains. The results will no doubt be widely cited and, perhaps more importantly, might finally put some of these lingering debates to rest.

I emailed Drs. Davis and Tong after ESCMID to congratulate them, and to inform them that I was planning to write this summary. They told me the manuscripts are headed to certain high-profile medical journals soon.

Hmm, wonder what those could be …

April 11th, 2025

Looking Back at a Defunct ID Meeting — and Ahead to a Thriving One

Ugly branded mug from an ICAAC meeting. Who would use this?

Back in prehistoric times, many ID doctors and microbiologists would gather each fall at a meeting to review the latest antimicrobial clinical trials and promising “bug-drug” studies of novel compounds in development. The meeting was called the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, abbreviated ICAAC.

There were a bunch of problems with ICAAC. First, everyone associates “chemotherapy” with cancer treatment, which of course this wasn’t. Second, the abbreviation (spoken “ick-kack”) sounded a lot like the emesis-inducing medication that once was used in emergency departments for poisonings. Third, it was often scheduled within weeks or days of the annual meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, or IDSA — or even jointly, creating a (very long) meeting, leaving everyone scrambling for espresso and searching for earlier flights home.

That it took place in the busy fall months, sandwiched between school starting and the holiday season, didn’t help.

Add to that the fact that ICAAC lacked a coherent identity. Was it a microbiology meeting? A clinical conference? A showcase for biotech and pharma, where investigators tried to sound convincingly enthusiastic about new drugs despite modest MIC reductions or a dubious noninferiority design? It was all of these things, and sometimes none of them.

In ICAAC’s giant exhibit hall, packed with displays from pharmaceutical and diagnostic companies, meeting attendees would receive “free” swag of sometimes comically useless items. Who wants to go to the supermarket with shopping bags emblazoned with the brand name of the latest fluoroquinolone, or a novel therapy trumpeting treatment success in “life threatening sepsis”? One of my friends would return home each year with what he considered the ugliest coffee mug of the conference; I believe the teicoplanin mugs frequently won the contest, perhaps a foreshadowing of the fact that the drug would never become commercially available in the United States.

Over time, the problems with ICAAC compounded. Attendance dwindled. And eventually, in an effort to rebrand and perhaps escape the shadow of its onomatopoeic curse, ICAAC was absorbed into a broader meeting: ASM Microbe, which takes place in June.

(Remarkably, another conference — the International Conference on Autoclaved Aerated Concrete, of all things — has since picked up the ICAAC acronym. Bold move.)

The annual IDSA meeting, now rebranded as IDWeek, took up some of the clinical trials slack when ICAAC stopped in 2015, but it’s never really hit its stride as a place to highlight breaking research. It’s more a meeting for state-of-the art reviews by experts in the field, and for catching up with former colleagues and co-fellows.

Today, the best meeting for practice-changing ID clinical trials has become the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) Global, which just to be confusing, was until 2024 called the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, or ECCMID. Every time someone says “ESCMID,” I still have to pause and translate back to “Oh right, ECCMID.”

For years now, many of the real practice-changing research studies in ID debuted at ECCMID (now ESCMID), and I have no doubt that this week’s meeting (which started today) will be similar. I’m not attending, but will be monitoring content from afar on Bluesky and whatever that other site is called that used to be so useful. Ironically, it was research studies presented at ECCMID that first clued me in to the power of social media for disseminating research, as even from my office here in Boston I could track the most important meeting content. For the record, it was the OVIVA study. Kind of a big deal.

So long live ESCMID, but here’s to ICAAC. May its memory live on, somewhere in the collective ID conscience, perhaps as an ugly teichoplanin mug — and may we all remember: if your acronym sounds like a cat coughing up a hairball, it might be time to rethink branding.

April 3rd, 2025

Gepotidacin — New Antibiotic or Rare Tropical Bird?

A Blujepa! (Drawing by Anne Sax.)

Imagine you’re birdwatching in the Costa Rican rainforest, Merlin app in hand. A flash of iridescent blue catches your eye. You scan the canopy and whisper excitedly:

Look, it’s the elusive Blujepa! A rare sighting!

No, not a real bird, but the brand name of gepotidacin, something rarer — and arguably more exciting — than a tropical bird, at least to us ID geeks: a brand new antibiotic class for treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections. That’s right, a first-in-class triazaacenaphthylene antibiotic, approved by the FDA on March 25 for the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections (uUTIs).

(If you’re wondering about pronunciation, I have on good authority it’s, JEP-oh-TIE-dah-SIN. Say it fast — it kind of sounds like an obscure progressive rock band, doesn’t it? Pretty sure Gepotidacin opened for Emerson, Lake & Palmer in 1974.)

Approval of the drug was the direct result of favorable clinical trials, EAGLE-2 and EAGLE-3. (Yes, more birds. You’d think this antibiotic came with feathers.) In both of these studies, 5 days of gepotidacin was noninferior to nitrofurantoin; in EAGLE-3, it also met criteria for superiority. The most common side effect was diarrhea, but it was overall well-tolerated.

So cue the ID fanfare.

(Muted trumpets only—we ID docs must always maintain antimicrobial stewardship mode. And let’s be honest — no one really knows what a “triazaacenaphthylene antibiotic” is, but that seems to be the convention to cite the biochemical structure of new antibiotics, as if any of us speak that language. Linezolid was frequently introduced as “the first oxazolidinone antibiotic”, whatever that means.)

To put this gepotidacin approval into context: the last time we had a new class of antibiotics for this indication, people were listening to Genesis and Yes and ELP on cassette tapes — maybe even 8-track tapes if you were stuck driving around your beat-up Chevy Nova. Since then, our therapeutic options have largely consisted of dusting off the same old standbys — TMP-SMX, nitrofurantoin, and if needed, fosfomycin or a fluoroquinolone. The last of these, of course, has tumbled out of favor, what with the tendons, the CNS effects, the QT issues, and the black box warnings piling up on your bedside table like overdue library books. And fosfomycin isn’t really that effective, is it?

Enter gepotidacin. Not only is it orally bioavailable — always a win for treating UTIs outside the hospital — but it also has activity against some resistant gram negatives that have increasingly shrugged off our old reliables. The drug inhibits bacterial DNA replication by targeting two essential bacterial enzymes: DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. This dual inhibition mechanism is unique, and different enough (we hope) from quinolones to limit cross-resistance.

Of course, the excitement is tempered by the usual caveats:

- the approval is currently for uncomplicated UTIs only

- it won’t be cheap (pricing is not available yet, but one can presuppose)

- the package insert includes a warning about avoiding the drug in people with QT prolongation — a caveat that also applies to quinolones.

Finally, approval of any new antibiotic is accompanied by the low-level anxiety that overuse will have us back where we started by the time we learn how to pronounce it properly.

Still, if gepotidacin can keep some patients with resistant E. coli out of the hospital and away from IV carbapenems, that’s a net win.

And if the distinctive call of the Blujepa brings to mind Rick Wakeman noodling through a virtuosic keyboard solo, well, that’s just a bonus. Take it away, Rick!

Ok, I’ll stop now. This is getting way too silly.

March 5th, 2025

What Is the Future of Treatments for COVID-19?

Photo by Alexey Komissarov on Unsplash

In this raging flu season, where people with influenza-related illness outnumber those with COVID-19 for the first time since the pandemic hit in 2020, we might be fooled into thinking that we no longer need better treatments for COVID-19. This would be a mistake — this virus still causes much misery, peaking each winter but circulating year-round, destabilizing lives everywhere.

But how will we get these better treatments? How can we do clinical trials with meaningful end points adapted to the current clinical spectrum of the disease? After all, what we have now has some big-time flaws.

These are the questions raised by the SCORPIO-HR study of ensitrelvir, just published in Clinical Infectious Diseases (of which I’m Editor-in-Chief), along with an insightful editorial commentary. Ensitrelvir is a SARS-CoV-2 protease inhibitor similar to nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), but it’s once-daily and doesn’t need the ritonavir; it’s already approved for use in Japan and Singapore.

In the study, around 2000 non-hospitalized adults with symptomatic COVID-19 were randomized to ensitrelvir once daily for 5 days or to matching placebo. The primary end point was time to sustained reduction of 15 COVID-related symptoms, with secondary end points of time to resolution of a smaller subset of symptoms, as well as viral load reductions.

For the primary end point, the study results were negative — time to resolution of all 15 symptoms was 12.5 days for ensitrelvir, 13.1 days for placebo, a non-significant difference. The treatment did better with secondary end points of time to resolution of 6 symptoms (stuffy nose, runny nose, sore throat, cough, low energy or tiredness, and feeling hot or feverish) and SARS-CoV-2-viral load reduction, both of these statistically significant in favoring ensitrelvir. The treatment was also well tolerated, with no detected safety events of note and rare virologic rebound.

So what should we do with these results? As with Paxlovid in a lower-risk or vaccinated population, ensitrelvir failed to achieve its primary end point. Yet the treatment was active for faster recovery from certain very common symptoms; whether one values this clinically would be a personal preference. One could argue that resolution of all symptoms set the bar too high for an antiviral in our current era of near universal pre-existing immunity.

In the accompanying editorial, Drs. Beatrice Zim and Cameron Wolfe take on the challenge of how to design clinical trials for COVID-19 when the clinical severity of the disease has so dramatically changed. They advise:

The largest unmet opportunity is likely for trial teams and regulatory authorities to be creative in building adaptive design into protocols that cannot only move with the evolution of therapeutics but also with the clinical landscape … Modified regulatory opportunities that are capable of handling modified trial design should be explored in preparation for future pandemics as we reflect on our successes and trial failures of the last few years.

Meanwhile, the venue for making such changes now faces an uncertain pathway. A planned meeting of government regulators, academic clinical trialists, and industry representatives to discuss trial designs for COVID-19 was cancelled unexpectedly earlier this year. Consider this meeting yet another casualty of changes at the top, which have included cancelled meetings on vaccines and reviews of submitted research grants.

Ugh.

But I don’t want to end on this (now familiar) depressing note, and finish instead with some brighter news — ensitrelvir as post-exposure prophylaxis reduced the incidence of COVID-19 in household contacts. It’s the first antiviral to demonstrate this benefit, one not observed with either Paxlovid or molnupiravir in prevention trials. We’ll see more details of this study presented at next week’s Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in San Francisco.

February 27th, 2025

Tragic Childhood Death from Measles Reminds Us That Some Don’t Understand Either the Medical Significance or the Human Heart

My ID colleague Dr. Adam Ratner, Chief of Pediatric ID at NYU Medical Center, just published an insightful and remarkably timely book called Booster Shots: The Urgent Lessons of Measles and the Uncertain Future of Children’s Health.

Chapter Six is entitled “Making Nothing Happen,” and it starts off with this especially profound paragraph:

Prevention can be a tough business. A pediatrician talks to a parent about choking hazards or sleep positions or bike helmets, but she never gets to know which specific children that advice has helped. You can’t see prevention unless you broaden your view, looking at populations over time. Getting rid of leaded gasoline decreases childhood lead poisoning; changing recommendations about infant sleep positions lowers the risk of sudden infant death syndrome. But you don’t get to know which kids benefited — who would have not worn that helmet and had the bike accident, tipped over that unsecured television stand, died of SIDS… Vaccines are one of our best tools for prevention. They are amazing inventions that prevent serious diseases so kids can get on with their lives. But you never really know exactly who they helped. Vaccines are masters in making nothing happen.

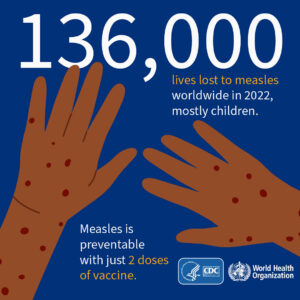

I emphasized the last sentence, because it is the opposite of this “nothing” that happened to that poor child in Texas — who by not receiving their recommended measles vaccine, missed the opportunity for “nothing” and now is tragically dead.

And some of the responses to this case, including from the very person charged with running our Department of Health and Human Services, reveal significant weaknesses in understanding both the medical significance of the case, and, just as damningly, the human heart — how we feel when reading about a childhood death. These comments clearly aim to downplay the importance of this outbreak in general, and the death of this child in particular, so I’ll follow them with corrections:

- “It’s not unusual.” In fact, the last measles death in the United States occurred in 2015, in an adult. So it’s the opposite of “not unusual.”

- “Outbreaks happen all the time.” This is the largest outbreak in Texas in more than 30 years. Measles was eradicated in this country in 2000, with sporadic cases happening only from international exposures. The drop in measles vaccination rates in some regions since then has led to some large local outbreaks — including this one in New York City which motivated Adam to write his book.

- “Those hospitalized are mainly there for quarantine.” Not according to the chief medical officer at the hospital, Dr. Laura Johnson, who said “We don’t hospitalize patients for quarantine purposes.”

- “Everyone I know had measles growing up, including me, and we all turned out fine.” That’s because with nearly universal infection, the denominator was huge. But before the vaccine became available in 1963, 400 to 500 people died of measles each year, most of them children. There’s your numerator.

- “It’s just one death out of 124 cases, while 1 in 36 kids has autism.” The measles vaccine does not cause autism. The original paper was based on fraudulent data, and later retracted; multiple other population-based studies have found no relationship.

- “If everyone else gets the vaccine, why should I have to worry about it for my child?” This isn’t so much a lack of medical knowledge problem, but a selfishness problem. Take a look at yourself in the mirror.

Let me turn now to why pediatric deaths and illness weigh so heavily in the minds of all healthcare providers and public health officials. It’s a lesson I’ve learned first-hand by being married to a pediatrician, watching my wife consumed with worry when a single patient in her practice is seriously ill. It’s captured well in this quote from Dr. Burton Grebin:

The death of a child is the single most traumatic event in medicine. To lose a child is to lose a piece of yourself.

This is why medical students, interns, and residents have so much closer supervision in pediatric teaching hospitals than in general hospitals. Why surgeons have to train an extra-long time to become pediatric specialists. Why pediatric practices field calls 24/7 from worried parents (especially first-time parents) about every little thing. (But some aren’t so little.) And it’s why the loss of a child is considered one of the most traumatic experiences an adult can have.

This is not ageism; this is human nature — who we are. And if the raw emotions don’t resonate, here’s some simple math: Let’s say this death in Texas was a 10-year-old child; the death robbed this person of approximately 70 years of life, of being part of and building a family, of contributing to our society. And it’s not just deaths that the measles vaccine prevents. A case of encephalitis with residual neurologic deficits could lead to decades of disability, with extraordinary individual and societal costs.

So let’s remember that lifesaving childhood vaccines are indeed “masters in making nothing happen.” In this case, nothing sure beats the alternative.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog do not represent those of NEJM Journal Watch, NEJM Group, or the Massachusetts Medical Society.

February 21st, 2025

The Language Grouch Returns

Plaster anatomic head, 1900.

If you’re an ID doctor, there’s a lot to be grouchy about these days. This. This. THIS! The list is long — and growing. Longtime readers with an interest in ID: I ask that you please contact your members of Congress to convey the harmful impacts of the workforce cuts at the CDC, NIH, VA, and other agencies. Thank you.

Now, on to the topic of today’s post — a break from the news but maintaining the grouchy mood to discuss some words or phrases I deeply dislike. We’ll come to a new one in a minute, but first a review of a few others already in my penalty box:

- HAART. I sense this one is vanishing, especially among us ID and HIV specialists — either that or people are afraid to say it in front of me. Seems that ART, standing for “antiretroviral therapy,” has finally triumphed. Hooray! Whether my campaign against HAART has anything to do with its demise is unknown, but I’m happy to take credit. In fact, I’ll add that to my CV now.

- Thanks in advance. As a reminder, I vastly prefer (even welcome!) a simple “Thank you” or “Thanks” when a person asks for something. My wife thinks this pet peeve of mine is beyond petty, saying “You want people to thank you and be appreciative, but at the same time you don’t approve their way of doing so. That’s not fair.” Good point — but a Thanks in advance innocently placed at the bottom of an email reminding me to complete my annual HealthStream modules, or a request for 3 learning objectives for an upcoming talk, still rankles. Oh well.

- Quick question. It’s possible every ID doctor gets hives when they hear this one, since the range of complexity in these “quick questions” is vast — and truly unknowable when someone starts out by greeting you with Can I ask you a quick question? I shared this distaste for the “quick question” prelude with an experienced (and excellent) nurse, and she told me I have misinterpreted the intent of the “quick” — it’s not to meant to demean the knowledge of the queried person (me), but to soften the impact of the curbside to follow. She’s no doubt right — people are trying to be nice! — so I’ve become much more tolerant of this one. Preemptive antihistamines are no longer required to prevent the hives.

But this is just a partial list. So today I’m bringing back the Language Grouch to introduce another unfavorite phrase — and this time it’s a common request:

Can I pick your brain?

Every time I see this one, I immediately think about what it means literally. This would involve cracking open someone’s skull, rooting around inside, and then using a sharp tool to pick at what most people consider the most important organ in the body. The fact that neurosurgeons do this routinely is still unfathomable to me, all these decades of being a doctor later.

But, as the saying famously goes, I’m no neurosurgeon (or rocket scientist), which puts me with roughly 99.999% of the population. And for us non-neurosurgeons, being an active brain picker would not only be inappropriate — it would also get us arrested. Don’t do it.

But of course the request is metaphorical — people who say, Can I pick your brain? aren’t asking to perform a craniotomy. What they’re after is information, not chipping away at your white or gray matter. I know this because I distinctly remember the first time I got the request, which occurred way back in my senior year of college, and no doubt explains my distaste for it. Pull up a chair, here’s the story:

I was taking a wonderful history of music course, the kind of broad survey that completely changes your life by introducing you to something you never really understood. It was the second semester, and we were on to some of the heavy hitters — Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schubert, Chopin, Brahms. The standard classical music canon.

Our “homework,” if you could call it that, consisted of going to the music library and listening to the greatest music of Western civilization in the listening lab, along with an annotated score. Homework! I distinctly recall listening to the opening notes of Beethoven’s Fourth piano concerto as one of my assignments, heard through the special headphones they gave us when we checked out the recordings. Hearing those gentle notes, then the early key change from the orchestra right after the opening, and reading along in the score — it literally gave me chills!

For some context, the early 20-something me had mostly been listening to Led Zeppelin, Blondie, Steely Dan, Elvis Costello, and The Pretenders — Genesis and Yes were the closest I’d come to classical music. Discovering these 19th century great works of music was a revelation. To call me an enthusiastic student barely begins to describe how happy this class made me. I couldn’t get to the lectures fast enough.

The course also had weekly small sections, taught by a fun and funny graduate student memorably named “Fla.” (It must have stood for something. I wonder where he is now. Definitely not picking brains.) I was the kind of student who, if you’re not really into this music stuff, you’d find annoying. In our weekly small teaching sections, I sat at the front of the class and actively engaged with Fla, absorbing his every word.

In the same class was a (sort of) friend of mine, who I’ll call Brian to protect his identity. I’m not saying his large size and ability to push people around and knock them over while wearing pads and a helmet helped him get into college, but just sharing that “talent” of his shows that I have my suspicions.

Not only was Brian indifferent to the charms of the music course, but he also teased me about what he considered my very teacher’s pet-like behavior. Most of the teasing happened in our dorm’s dining hall because he stopped going to the small sections early in the course.

But when it came to prepare for our final exam, Brian reached out to me because there was simply no way to cram the listening assignments into the time he had remaining before the test. Listening to music takes time — you can’t speed it up, they’re not digital podcasts.

Not only that, one of the goals of the small sections was to highlight the most important material, always a harbinger of what was to be on the tests. And Brian had only attended a tenth of the classes — and I’m being generous with that estimate. Fla held no charms for him.

So here’s what Brian said (he was a last-name-first user):

Hey Sax — can I come over sometime and pick your brain about the key material for the music final?

How would you have responded?

Take it away, Ludwig. This music still gives me chills.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog do not represent those of NEJM Journal Watch, NEJM Group, or the Massachusetts Medical Society.

February 14th, 2025

This Year Influenza Came Back to Remind Us It’s Not Messing Around

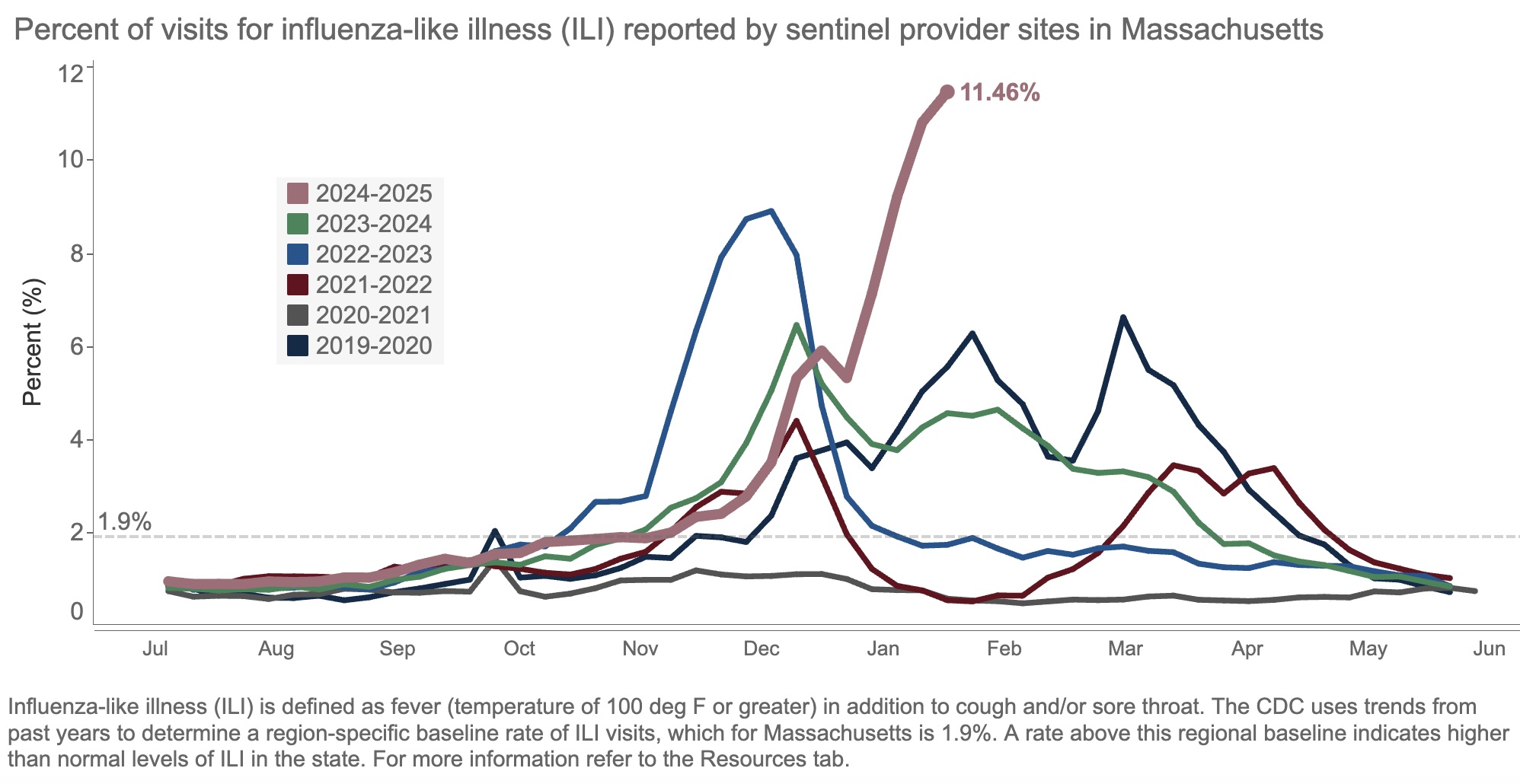

If it seems like pretty much everyone you know either has the flu or is recovering from it, it’s because we’re in the middle of the worst flu season in over a decade.

Take a look at this figure, from our state’s surveillance data, updated yesterday:

The result of all this “influenza-like illness”? Patients are deluging outpatient clinicians with messages about fevers, sore throats, coughs, and related symptoms. Hospital beds and ICUs fill up with chronically ill people whose condition has worsened due to the flu. Emergency rooms, already overstrained, park sick people in hallways awaiting evaluation and treatment.

Yes, it’s bad out there, folks. This week, we heard that our hospital has four times as many people hospitalized with the flu than as those hospitalized with COVID-19, the first time this has happened since the pandemic.

One of the most common questions we ID doctors get when the flu season is bad, or late, or just strange, is, “Why this year?” The honest answer is this humble three-word sentence:

We don’t know.

Some have blamed the cold weather this winter without much in the way of a significant thaw. Maybe, but other cold winters haven’t necessarily had this much flu. Plus there’s plenty in southern states.

Others cite the low rate of influenza vaccination, in reaction to overzealous (in some views) COVID-19 vaccine recommendations. Perhaps, but this has never been a popular vaccine.

A third theory is the fact that masking and other infection prevention activities in the community have ended. I doubt it’s this because masking was pretty much over last year and even the year before.

Some have asked me if this year’s strain of flu is somehow different, and the answer is that surveillance molecular data do not so far suggest this is the case. This is in contrast to the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, where during April (!) flu cases surged because of the emergence of a novel H1N1 variant to which younger people had little immunity.

Related, one cause of this year’s high number of cases emphatically isn’t a flood of cases of “highly pathogenic” avian influenza, H5N1. Despite active surveillance at the state level, we still are not seeing this illness from this strain to a significant degree — fortunately!

Note that I put the words “highly pathogenic” in quotes. H5N1 is of course of great concern because we have no natural immunity to it. If it emerges as a human-to-human pathogen, we’re looking at an explosion of cases, analogous to or worse than 2009. That’s bad enough.

But another major worry is that it might be intrinsically more virulent, more likely to cause severe disease per case. But the cases of H5N1 reported thus far in the United States from animal sources have had a wide spectrum of severity. At one extreme there has been a death, and at least one ICU admission; at the other end of the spectrum, many have had mild illness (conjunctivitis seems particularly common), and a recent serologic study in 150 bovine veterinary practitioners found 3 positive cases — all asymptomatic.

So I’d propose we remove the two-word phrase “highly pathogenic” as a common modifier of H5N1 until we really know whether it deserves this scary label — not just in birds and cats, but also in humans.

And please, let’s press on with the following:

- Active influenza surveillance, with transparent reporting of data. This recent government action to reduce the CDC workforce will not make this easier. To quote one of my former colleagues who works there right now, “It’s a very sad time for public health.” 100% agree.

- Re-invigorated research to improve the flu vaccine. That universal flu vaccine can’t come soon enough.

- Further drug development to improve flu treatment. Can I interest anyone in interferon lambda again, which was effective in COVID but never developed? It’s a potential treatment for respiratory viruses that may be agnostic to etiology.

Here’s hoping.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog do not represent those of NEJM Journal Watch, NEJM Group, or the Massachusetts Medical Society.

February 6th, 2025

Could This Be the End of PEPFAR?

Short email from a longtime colleague, working in Africa at a PEPFAR site:

Without USAID, PEPFAR is essentially dead.

I got chills reading this.

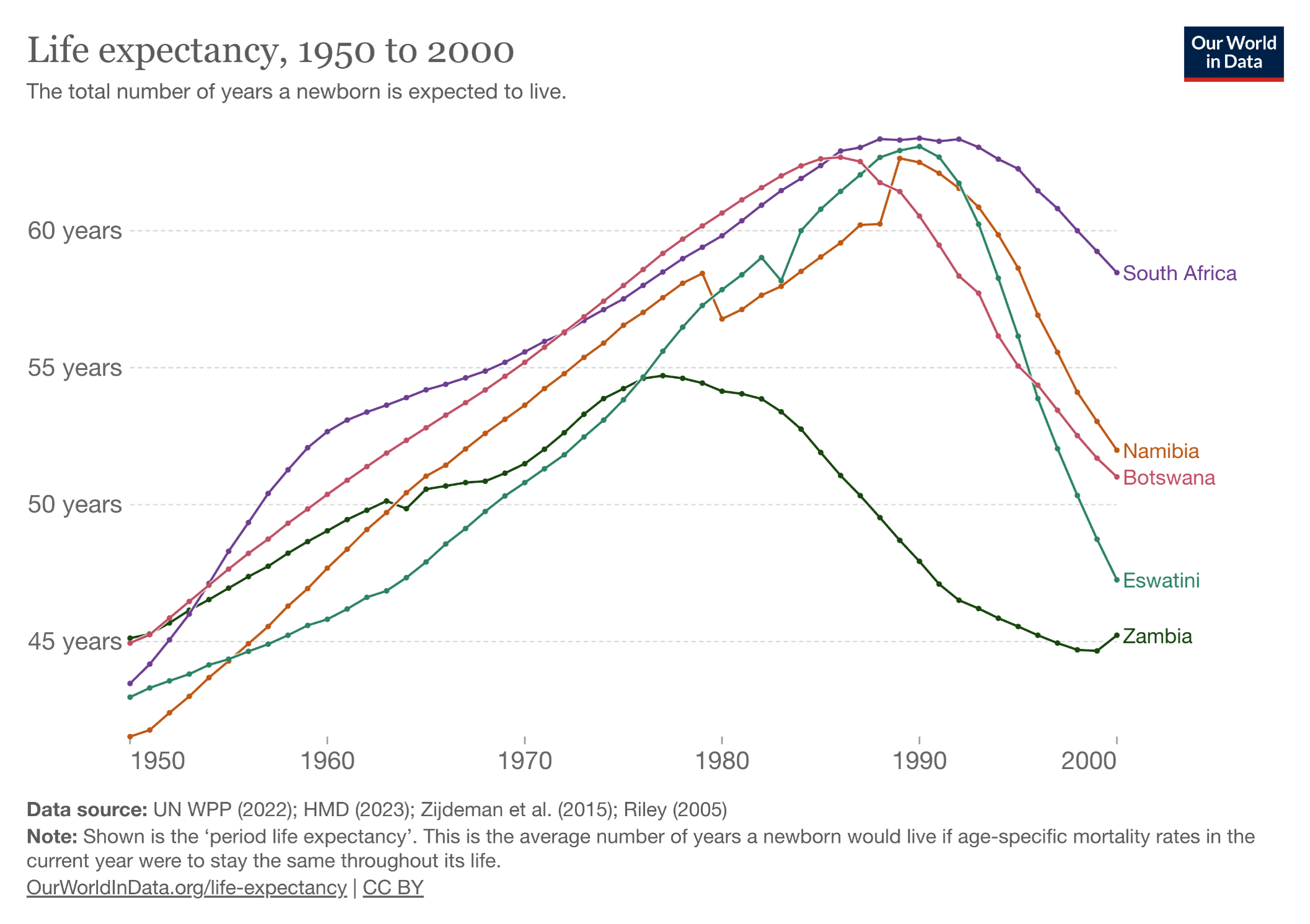

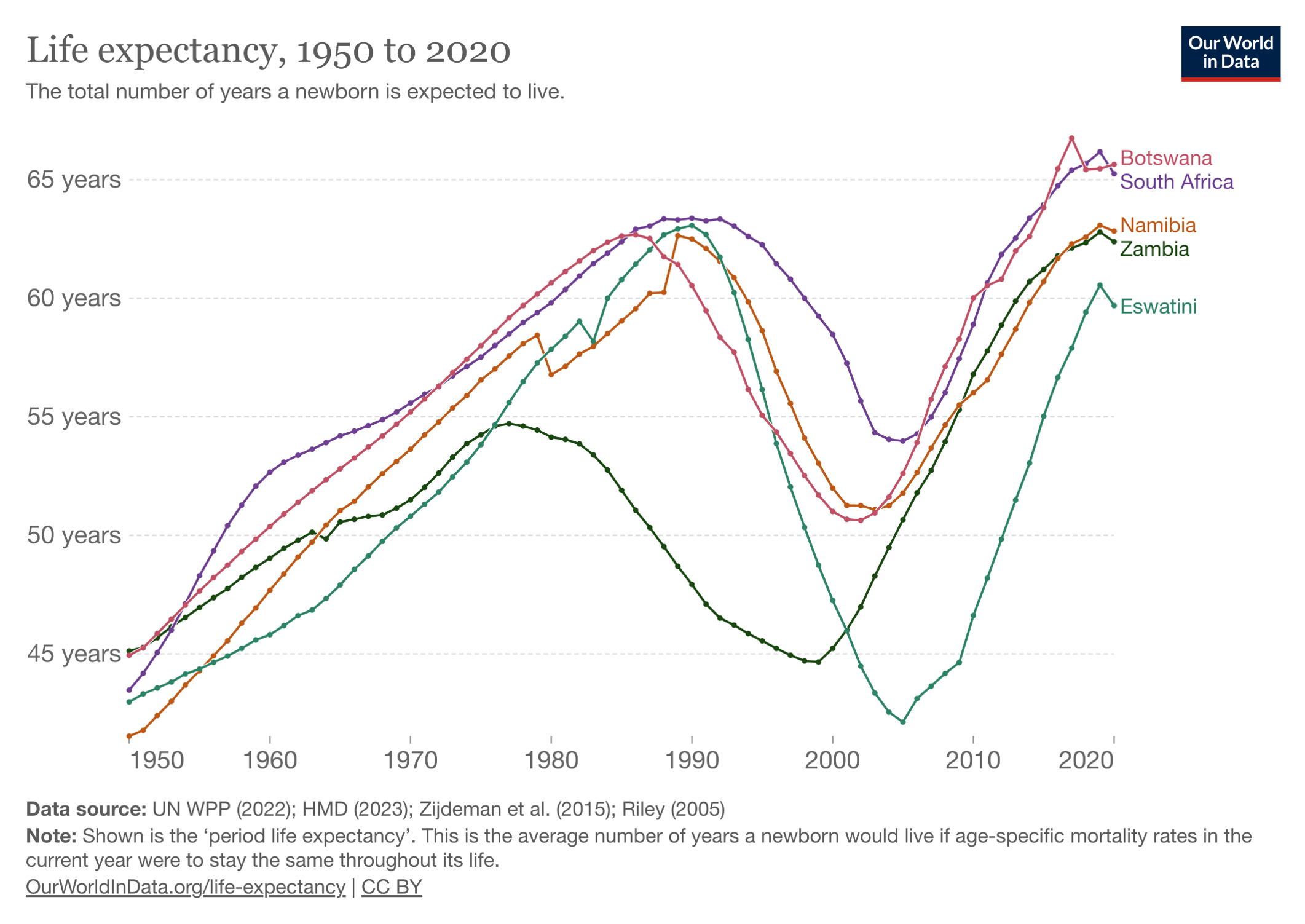

PEPFAR, the abbreviation for the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, started in 2003 under the direction of President George W. Bush. To say it’s been a resounding success undersells the impact of the program. Take a look at these two graphs, first the trend in life expectancy in several African countries (all PEPFAR recipients) before access to HIV therapy:

Now let’s look at what happened after the broad roll-out of HIV treatment, greatly facilitated by PEPFAR:

The PEPFAR program shows what happens when you pour resources into a devastating problem with a highly effective solution — in this case, a rapidly progressive and fatal disease of younger people (AIDS), with subsequent halting of that disease with antiretroviral therapy. Widely cited — and credible — estimates are that PEPFAR has saved more than 26 million lives. It has been so effective that for years it garnered bipartisan support from U.S. politicians who otherwise agreed on hardly anything.

What does USAID have to do with PEPFAR? USAID collaborates with PEPFAR and local partners to implement HIV programs, ensuring the delivery of antiretroviral therapy and other critical services. The sudden freeze in aid disrupts these efforts, potentially jeopardizing the health of countless individuals who rely on consistent HIV care. To quote again my colleague:

USAID manages the supply chain with multiple donors and products — drugs, reagents, equipment. They represent a substantial portion of the PEPFAR budget in my country.

Some have argued that provision of HIV care internationally should shift to be the responsibility of the host countries, especially now that ART has become so inexpensive and widely available. While I understand this argument, isn’t the sensible approach to make this transition gradually, or at least with some warning? And what about the other essential work of USAID? If this action is done solely to save the Federal government money, it’s not going to have much effect. As a reminder, only around 1% of the Federal budget goes to economic foreign aid, and not all of that to USAID.

Beyond the primary concern, which is the health of individuals receiving care and treatment through this program, there’s the reputation cost for our country. A country that supports effective foreign aid in poor nations is considered generous and kind; one that suddenly pulls such aid the polar opposite — selfish and cruel. Another communication from a colleague in a different country:

As a result of the PEPFAR/USAID freezes, we lost a third of our staff in our HIV clinic, mostly people who dedicated their entire professional lives to the clinic. The offices are empty and corridors echo where they didn’t before.

Let’s contrast this with the joy this program engendered when it started. I distinctly remember meeting a doctor from Nigeria in the early days of PEPFAR; he was smiling broadly at the extraordinary effectiveness of ART that he could now give to literally hundreds of his patients. Shaking my hand, he said — “We cannot thank you enough. Please tell President Bush.”

I never met the former President, but I certainly would do so if I had the chance.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog do not represent those of NEJM Journal Watch, NEJM Group, or the Massachusetts Medical Society.