An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

May 12th, 2019

On Mother’s Day, a Tribute to a Mother Who Doesn’t Celebrate Mother’s Day

My siblings and I are pretty lucky, because our mother may be the smartest person in the world.

My siblings and I are pretty lucky, because our mother may be the smartest person in the world.

Let me reassure you that this is not just our biased opinion. Everyone who knows her well thinks the same thing — including my wife, who told me today, on Mother’s Day, that my Mom’s remarkable brainpower should be the focus of this profile.

(Not that my mother has any time for Mother’s Day. Unsentimental in the extreme, she disparages such holidays as manipulative.)

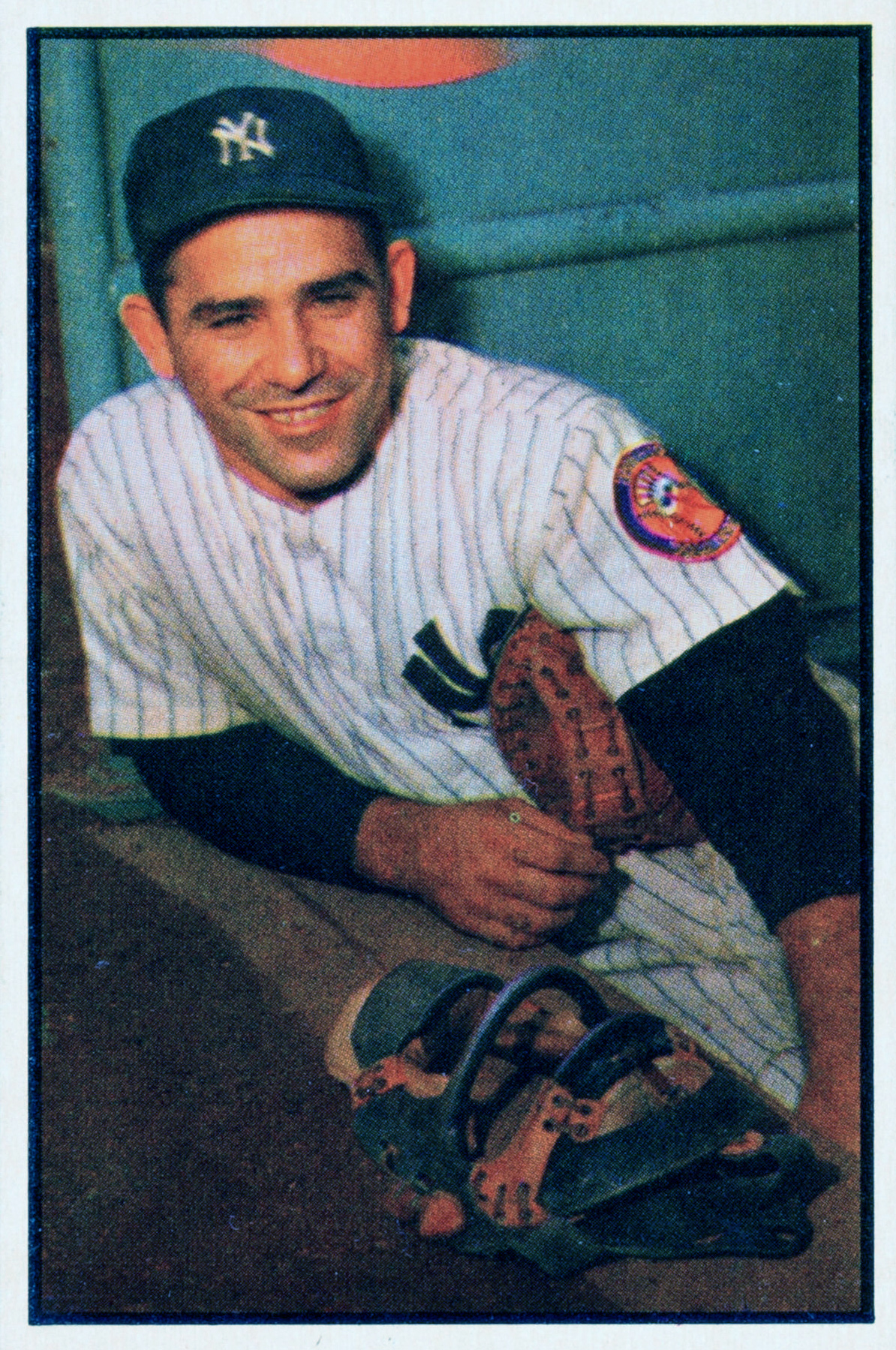

I first had an inkling of her intellectual superpower when, after underperforming on an important test in middle school due to numerous trivial distractions (baseball, model rockets, general silliness), I received some stern comments of disapproval from my father.

When my mother rushed to my defense, he countered as follows:

Look, no one is as smart as your mother. Most people have to study to do well in school.

I assure you this was said without the slightest exaggeration.

The first person in her family to attend college, she graduated early then followed the path of many women of her generation — married at 21, done having three children by 26 (!), she could have continued down this path of domesticity without anyone even noticing.

That’s what most women did.

But she went back to get a graduate degree (abandoning little me at home, sob), then started a successful career as a food writer, continuing to work as a journalist (Newsday, New York Daily News, Bon Appetit) for many years. In 2000, as the internet took off, she won a James Beard award for Best Internet Writing.

As this point, I know what you’re thinking — how could a food writer be the smartest person in the world? Surely that honor must go to a neuroscientist, a mathematician, a scholar of ancient histories, some super-linguist who speaks 20 languages.

Well, here are a few examples:

- Technology. Most people my mother’s age really don’t do well with new technology — remember the flashing clock on the VCR? But my mother was an early adopter of computers, owner of one of the first word processors — does this Wang 2200 look familiar to anyone? Although she’s not writing code or macros, she effortlessly uses computers and cell phones as tools to get things done — which is probably what most of us should do rather than obsess over the latest gadget.

- Breadth. My mother’s expertise extends way beyond food — literature, art, music, movies, theater, current events, all seem to be in her domain. My daughter is constantly amazed at how her grandmother — my mother — gets most pop culture references. During a video interview I did with many family members at the turn of the century, I asked her what she believed to be the greatest unheralded work of art. She paused briefly and said: “Eugene Onegin — and that’s because I just read the novel, saw the opera, and rented the movie.”

- Math and science. Though she has degrees in art history and English literature, I can talk to her about advances in medicine and science without the slightest need to bring down the level. It’s particularly remarkable how quickly she grasps key principles of clinical research and epidemiology, concepts that many of us spend years mastering — examples include confounding, sensitivity and specificity, lead-time bias, the potential harms of excessive screening. Explain these principles once, she gets them forever.

Not included in the above Mother’s Day (sorry Mom!) tribute is that she’s been consistently supportive of my brother, sister, and me in all our life and career decisions. When I ditched a cardiology fellowship for the much less remunerative — and even stigmatized — specialty of infectious diseases, she never once even hinted at displeasure.

So thank you, Dad, for choosing this very smart and wonderful person to be our mother.

She’s so special that I can even forgive her these two transgressions, both of which stem from this aforementioned lack of sentimentality:

- She threw away my baseball cards when I went to college. Why should anyone save these boring pieces of cardboard?

- She doesn’t get this whole dog thing. After all, they’re just animals.

Hey Mom, Louie forgives you, too.

May 5th, 2019

Latest Published Study on HIV Treatment as Prevention Is Déjà Vu All Over Again, But Some News Is So Good It Never Gets Old

Even if you’re not an ID or HIV specialist, there’s an excellent chance you’ve heard of the PARTNER2 study, just published in The Lancet.

If not, the title could not be more descriptive:

Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive partner taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy

And, in case you’ve just awoken from a Rumpelstiltskin Rip Van Winkle-length sleep, here are the results:

The risk is essentially zero.

This is far from the first time we’ve heard this information, either from this or other (HPTN 052, Opposites Attract) studies.

The formal publication of PARTNER2 therefore has a déjà vu quality to it, one which prompted Myles Helfand, the indefatigable and entertaining Executive Editor of the terrific HIV resource TheBody, to post the following:

Breaking: A fact we've already known conclusively for about three years https://t.co/YYML1z8igh

— Myles Helfand (@MylesatTheBody) May 3, 2019

“Breaking” indeed. Ha. To Myles, and to many of us, this is old news. The publication of the paper after years of comparable findings from this and other studies may seem anticlimactic, no big deal.

He’d no doubt cite that even this particular study was presented first at the AIDS 2018 conference last summer in Amsterdam. That’s over 8 months ago! Ancient history!

But here’s another take from Claire Farel, an ID doctor from the University of North Carolina (and, full disclosure, a wonderful graduate of our ID fellowship program):

Another boost to our conviction that #UequalsU and hopefully to the fight against #HIV stigma. Discussing U=U with patients has been a gift, leading to some of the most profound conversations I’ve had in medicine. Also, there’s never enough Kleenex. https://t.co/jC7iMhSQZ8

— Claire Farel (@claire_farel) May 3, 2019

(For those not in our field, that “U=U” stands for “Undetectable = untransmittable.”)

First, I am in complete agreement that telling people with HIV that their treatment prevents viral transmission is a “gift,” leading to profound and anxiety-relieving responses. It’s just as good as informing patients that if they take their HIV meds, they will not die of AIDS — and both pieces of information are equally true.

Conveying this information elicits such relief that yes, tears of happiness are often part of the mix, if you’re wondering about that Kleenex reference.

Second, the publication of a study in a peer-reviewed journal still lends far greater authenticity to scientific data than conference presentations or abstracts. This is particularly true when the journal publishing the paper is a prestigious one, such as The Lancet.

(I have cleared it with the Editorial Office that we’re allowed here at NEJM Journal Watch to write that The Lancet is prestigious. Note I didn’t say MOST prestigious.)

Don’t get me wrong — I agree that conference presentations play a critical role in rapidly getting important new data into the public domain. But there’s still room for distribution the old-fashioned way, in a journal, which is why I posted both Myles’s and Claire’s responses to this publication.

Before we leave this study, we must linger for a moment on the most unintentionally amusing sentence from PARTNER2.

It’s this:

In total, couples reported having condomless anal sex approximately 76,088 times during eligible couple-years of follow-up.

Something about the precision of that estimate — are they sure it wasn’t 76,089? — makes me smile every time.

April 28th, 2019

Even More Fun with Old Medical Images

Loyal readers of this site might note that we periodically stray from incisive, topical coverage of our exciting field of Infectious Diseases, and venture off into subjects that may or may not be ID-related.

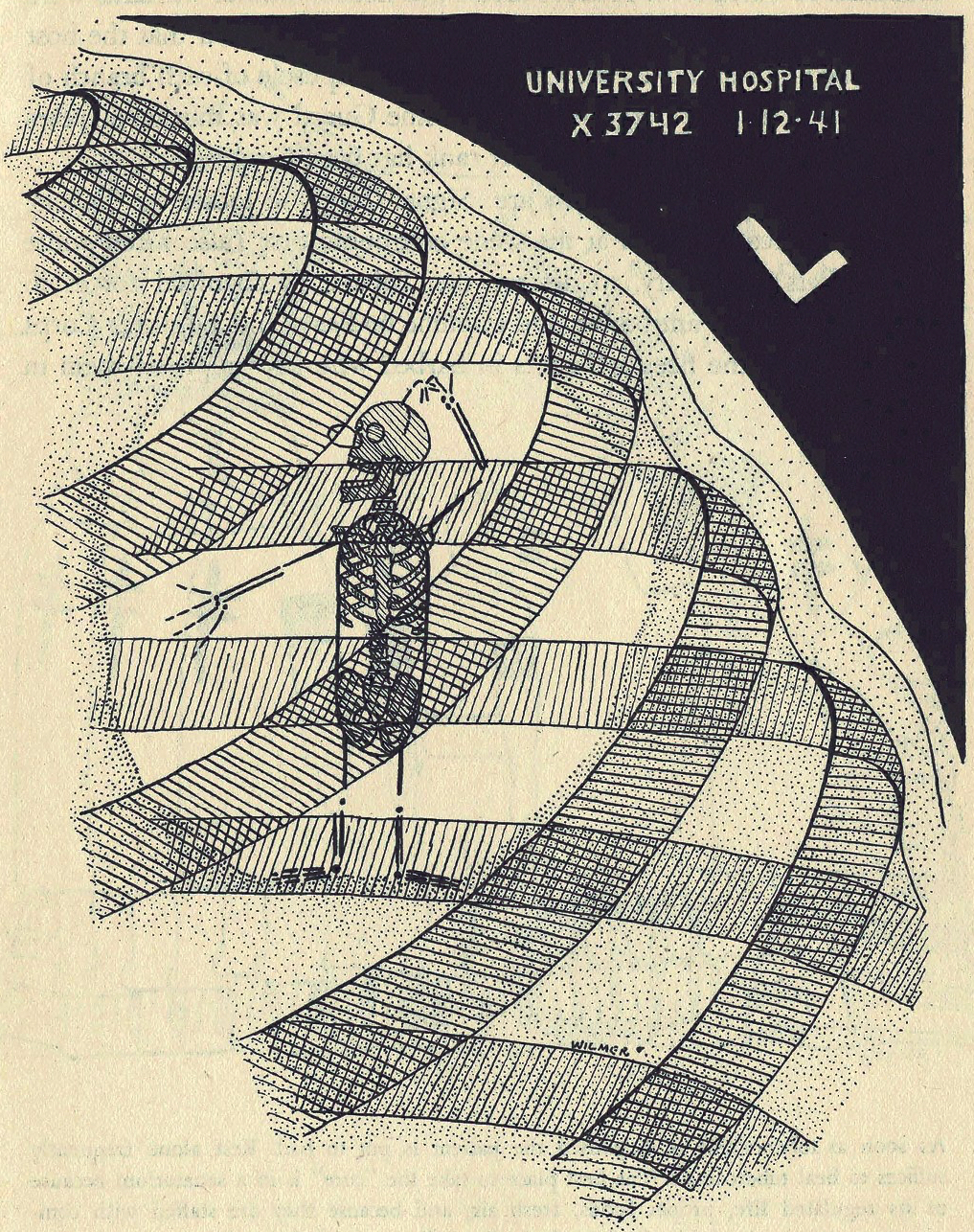

And good news for fans of this approach, because today it’s time to release our third episode of Fun with Old Medical Images.

Why today? The simple answer is that this feature appears on this site during certain holidays on the pre-Columbian Mesoamerica calendar, a calendar widely used by the Maya for centuries. I find it an excellent resource when trying to solve difficult scheduling problems.

As a reminder, here’s how Fun with Old Medical Images works: I choose an old image from the vast National Library of Medicine collection. Then, I make up a caption and provide a brief commentary.

All this is done for you free of charge — guaranteed without hidden registration or subscription fees.

Off we go, #1:

Though he accidentally left his white hat at home, Bailey was kindly still allowed by the nurses to pose for the team photo.

What a generous group! And you go, Bailey — such a good boy, sitting so still. And those pointy, asymmetric ears are adorable.

Let’s move right on to #2, into the OR:

Even after Dr. Griswold returned from his studies in Vienna with the latest techniques in sinus surgery, his patients continued to feel some pre-op apprehension.

Not surprisingly! And I’m growing more dubious about Dr. Griswold’s Viennese studies every day.

#3 finds us in a recreational pool for frogs:

Freddy the Frog loved the hoop dive game so much that he continued to play long after his friend had grown tired and gone home.

Say one thing for Freddy — he sure is fit! But doesn’t he know it’s time for dinner?

And in case you’re wondering, these two images are an old test for strabismus. Somehow.

Speaking of pairs, I bring you two trendy guys for #4:

The latest dance craze — don a bodysuit, shave your head, and pretend you have no neck. Fun for all!

I hear everyone’s been doing it — The Naked Bald No-Neck Strut. Kids today and their crazy dances!

Heading to #5, with a big challenge in our appearance-obsessed, digital era:

Despite generous use of Photoshop, there was only so much Connor could do to improve his Tinder profile picture.

Alas, Connor — dates will have to learn not to judge a book by its cover, your skilled Photoshop efforts notwithstanding.

Finishing with an even half-dozen, here’s #6, which brings us back to familiar ID territory:

Oh, you silly tuberculosis bacillus — we know how to find you!

So that wraps up today’s tour of Even More Old Medical Images. Please join us next time when we’ll be back with our usual erudite content.

But until then, enjoy this:

April 22nd, 2019

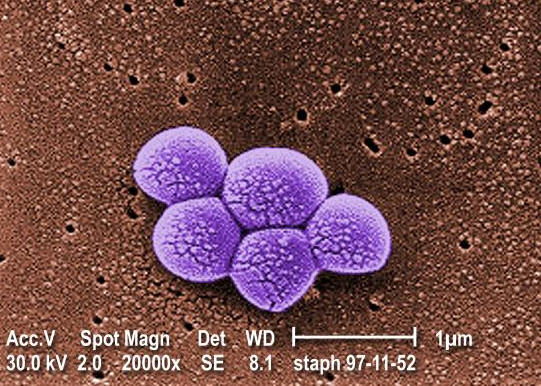

Two New Trials of Combination Therapy for MRSA Bacteremia Answer Some Questions — and Raise Several New Ones

Every clinically active ID specialist, hospitalist, and cardiologist realizes that treatment of bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant Staph aureus (MRSA) is no easy task.

In fact, it’s a problem so difficult that persistent bacteremia due to MRSA deserved highlighting here as an “Unanswerable Problem in Infectious Diseases”.

I wrote that over 5 years ago, and you know what? It’s still unanswerable!

One likely reason for the difficulty is that vancomycin kind of stinks as an antibiotic — there are molecular, pharmacologic, and potentially even immunologic reasons why it underperforms compared to beta-lactams.

Now, we have two new clinical trials to help move the field forward.

The first is the CAMERA2 study, just presented by Steven Tong at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID), with summary below thanks to Erin McCreary:

https://twitter.com/ErinMcCreary/status/1118093904719618048?s=20

The study asked the question of whether adding a beta-lactam to standard of care therapy (vancomycin or daptomycin) would improve outcomes for adults with MRSA bacteremia. Some 356 adults were randomized to receive either monotherapy (vancomycin mostly, with some daptomycin) or combination therapy of vancomycin or daptomycin plus 7 days of an anti-staphylococcal beta-lactam (flucloxacillin, cloxacillin, or cefazolin).

The primary outcome was a composite one of several endpoints, looking at:

- 90-day mortality

- Persistent bacteremia at day 5 or beyond

- Microbiological relapse

- Microbiological treatment failure (positive sterile site culture for MRSA at least 14 days after randomization)

As pictured here, there was no significant benefit of combination therapy over standard of care — even though clearance of bacteremia was faster in the combination arm. The limitations of time to blood culture clearance as a surrogate endpoint echo what we learned previously when evaluating adding aminoglycosides to beta-lactams for treatment of MSSA — faster clearance of blood cultures, but no clinical benefit.

Importantly, participants who received combination therapy had significantly more acute kidney injury, and numerically higher mortality, leading to early termination of the trial. The post-hoc analysis showed that this renal toxicity was far greater with flucloxacillin/vancomycin than cefazolin/vancomycin, and hence the former cannot be recommended.

So, is that the end of combination therapy of vancomycin plus a beta-lactam for MRSA? Certainly not — as noted above, vancomycin treatment strikes most of us as suboptimal, and daptomycin is no better. In addition, the vancomycin/cefazolin strategy in CAMERA2 appears to be safe and may provide greater antimicrobial activity without increasing toxicity. The lead author suggested that this combination may be the next one tested by this group.

The second clinical study in MRSA bacteremia is a recently published pilot trial that randomized 40 patients with MRSA bacteremia to receive either vancomycin or the combination of daptomycin plus ceftaroline — italicized since it is the only FDA-approved beta-lactam with activity against MRSA, and hence fundamentally different from the combination strategy tested in CAMERA2.

Here are the surprising results:

Although the study was initially designed to examine bacteremia duration, we observed an unanticipated in-hospital mortality difference of 0% (0/17) for combination and 26% (6/23) for monotherapy (P=0.029), causing us to halt the study.

Wow.

But before we get too excited, here’s a critically important caveat — with such small numbers, these results could have occurred by chance, especially due to an imbalance of randomization (there were more patients with advanced lung cancer in the monotherapy arm). The authors acknowledge that the results must be considered preliminary due to the small sample size, and strongly encourage a fully powered study of this approach. Agree!

But what about ceftaroline alone? The drug is only FDA-approved for skin/soft-tissue infections and pneumonia; the lack of controlled data on ceftaroline therapy for bacteremia is an unfortunate data gap.

So, here’s a proposed study for MRSA bacteremia — a three-arm, randomized trial comparing:

- Standard-of-care (vancomycin or daptomycin, investigator’s choice)

- Ceftaroline alone

- Daptomycin/ceftaroline

Hey, we ID doctors can dream, can’t we?

April 14th, 2019

Here’s One “Rule” of Medical Education That Needs Fixing — Or at Least a Little Context

Like any card-carrying ID doctor, I enjoy teaching about antibiotics. Give me a whiteboard (small group), or a PowerPoint set-up (lecture hall), and I’m off and running.

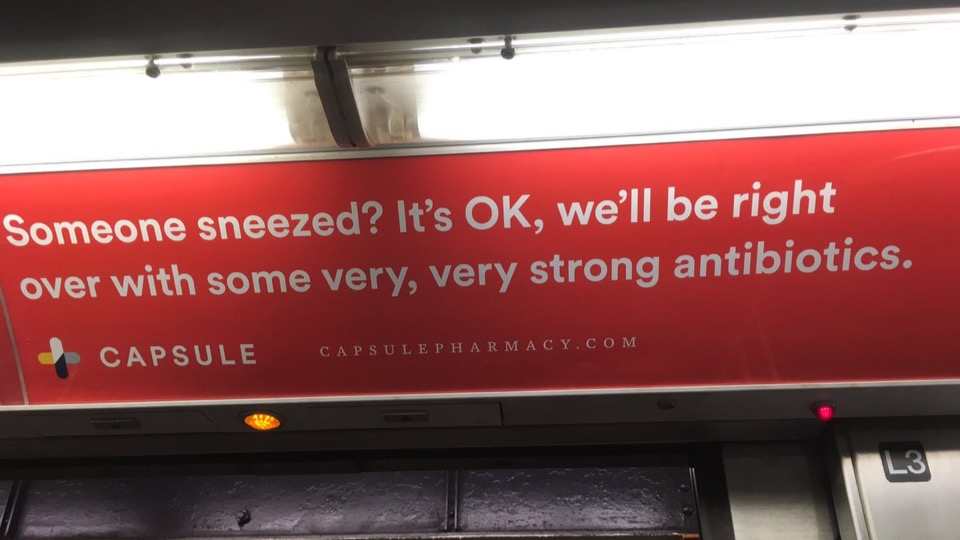

Not surprisingly, an important theme of these talks revolves around avoiding antibiotic overuse. Over the years, I’ve collected a few egregious examples of how marketing distorts public perception of antibiotics — and, in particular, their indications.

These images are fun to show in my talks — and, quite explicitly, to mock.

Here’s one:

Free Antibiotics! Just in time for “Cold and Flu Season!” How generous!

And here’s another, an ad I spotted on the NYC subway a couple of years ago:

“Very, very strong antibiotics” for someone who “sneezed.” Brilliant. Those strong antibiotics will be just the thing.

Let me state the obvious — these ads reinforce the very wrong belief that people with viral respiratory tract infections benefit from antibiotics. This misconception drives much of the inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in outpatient care and emergency rooms.

By showing the images, I’m hoping to demonstrate just how pervasive these incorrect views are. It’s a brief and entertaining (I hope) diversion from the more didactic parts of the talk.

But not so fast — the last two times I submitted slides for post-graduate courses, I received notice that these images were in violation of Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) standards, specifically:

STANDARD 4.3Educational materials that are part of a CME activity, such as slides, abstracts and handouts, cannot contain any advertising, corporate logo, trade name or a product-group message of an ACCME-defined commercial interest.

But here’s a question for the ACCME folks — doesn’t the context of these images matter? This usage is hardly promotional. It’s just the opposite, I’m making fun of these ads.

And here’s a second question — do you think we live in an advertising-free world? Wouldn’t the learners’ education be furthered by seeing examples of how misleading commercial claims can be?

One of the two courses relented when I made my point — slides stayed in. The other one, no such luck. I’m taking my revenge out on this inexplicable ruling by posting the images here.

But all this back and forth reminded me of this quite brave (and brilliant) statement by the iconoclastic Dr. Vinay Prasad — who no doubt expresses what many medical educators have thought over the years, but never have been so bold to say:

https://twitter.com/VPrasadMDMPH/status/1114221315265679360

And since Tom Lehrer just turned 91, and this is a post about education, I can’t resist sharing this brilliant song and video:

April 7th, 2019

New York Times Highlights the Problem of Antimicrobial Resistance — and the Tricky Issue of Disclosure

Right there, on the homepage of today’s New York Times, our national paper of record — Sunday edition, no less! — appears this headline:

A Mysterious Infection, Spanning the Globe in a Climate of Secrecy

Most of this piece is about Candida auris, the highly resistant fungus that targets our most vulnerable patients — those with weakened immune systems due to extremes of age, comorbid medical problems, cancer chemotherapy, or immunosuppressive drugs.

The authors do an excellent job bringing attention to the seriousness of the problem. They provide some theories about its origin and cite the many challenges each Candida auris case brings to hospital workers, in particular those in charge of Infection Control.

But there’s a second message in this piece, one highlighted by the difference between the online headline and the one in print.

Online: A Mysterious Infection, Spanning the Globe in a Climate of Secrecy

Print: Fungus Immune to Drugs Quietly Sweeps the Globe

It’s that Climate of Secrecy phrase, implying there’s a widespread cover-up effort.

Indeed, there’s a distinct tone of blame in the article directed squarely at institutions that failed to disclose problems with Candida auris. One person quoted likened it to a restaurant failing to disclose that it had a food poisoning outbreak.

But with the caveat that I don’t work at the institutions cited in the article, I emphatically wish to state that we ID specialists strongly welcome all publicity about the seriousness of antimicrobial resistance.

In fact, if you want two messages about which we have 100% unanimity, here they are:

- Vaccines work, prevent illness, save lives, and save money — the risks are vastly outweighed by their many benefits.

- The overuse of antimicrobial agents leads to a dangerous increase in drug-resistant microorganisms, and this is a huge local, national, and global threat.

Read what Infection Control specialist Dr. Dan Diekema wrote after he saw the piece in the Times — he was “Happy to see” that this important issue had risen to such prominence:

Happy to see that an emerging, antimicrobial-resistant, healthcare-associated pathogen has made the FRONT PAGE of the NYT! The reporters do a good job placing C. auris in larger context..@PaulSaxMD @mike_edmond @eliowa 1/9 https://t.co/OH1ioEWJRT

— Dan Diekema (@dan_diekema) April 6, 2019

He (and all of us) are even happier that there’s another piece in the Times on antibiotic resistance, here describing how the combination of antibiotic overuse, crowding, and poor sanitation inexorably drives up resistance rates in low and middle income countries.

So, if there’s a cover-up about this important problem, it’s not coming from us ID doctors.

One last point — while I am all for transparency and disclosure if it improves patient safety, the public must realize that having patients with drug-resistant infections within the walls of a hospital by no means proves that these clinicians and Infection Control departments provide substandard care.

As noted above, it’s frequently the sickest, most complex, and vulnerable patients who develop these infections. Often they are transferred from other institutions after prolonged hospitalizations, with many weeks of antibiotic exposure before they even reach our inpatient wards, and they already harbor resistant bugs.

It would be a shame if tertiary-care hospitals viewed mandatory disclosures of resistant infections as a disincentive for providing care to these patients, who arguably need advanced care the most.

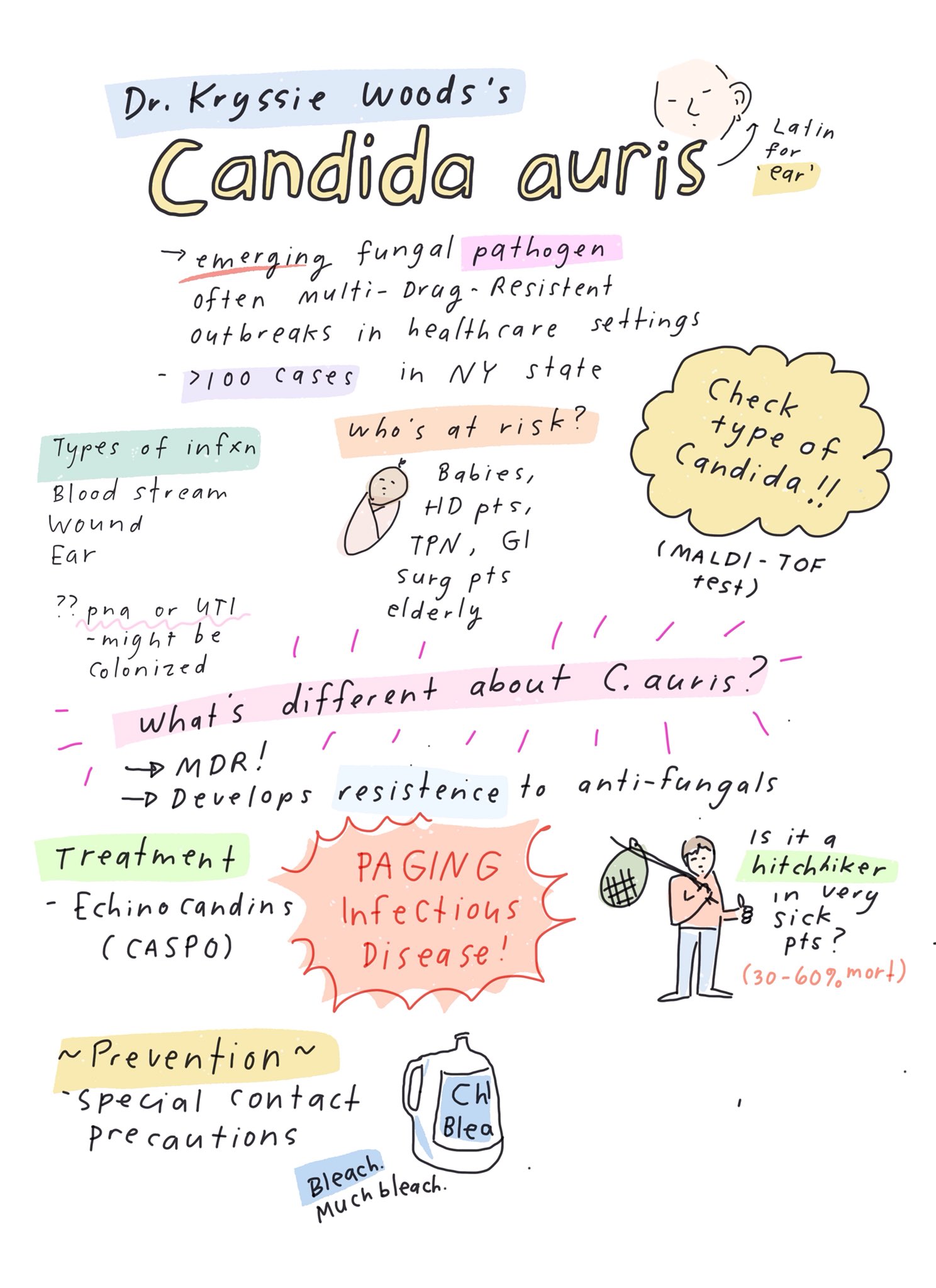

Meanwhile, here’s a wonderful summary of some key learning points about Candida auris — presciently sketched out by cartoonist-MD Dr. Grace Farris a couple of weeks before the Times piece was published. Thank you, Grace!

March 31st, 2019

The Problem with Research Posters — and a Bold Approach to Fixing Them

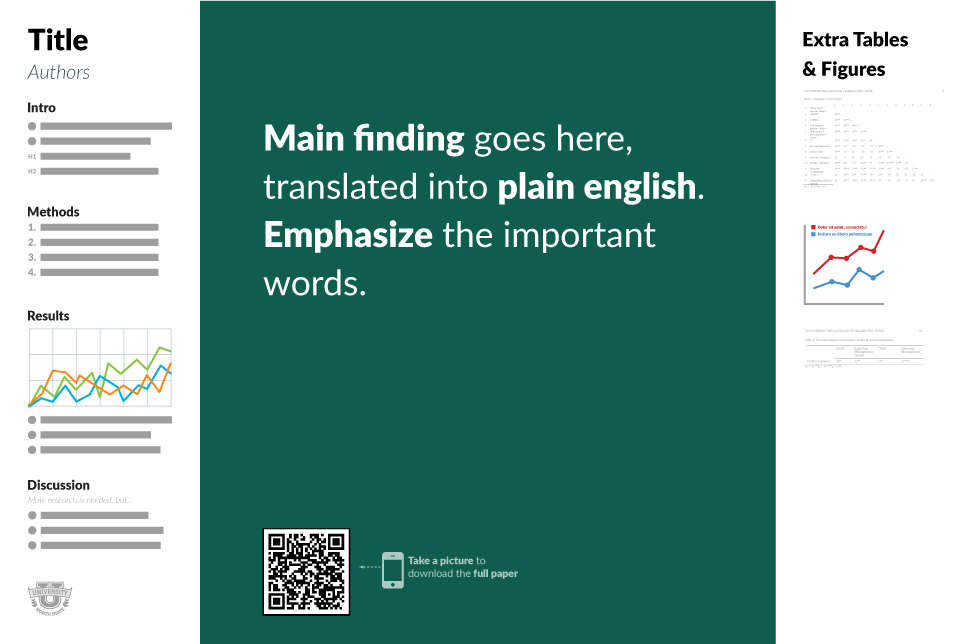

The scientific poster, as envisioned anew by Mike Morrison.

When submitting an abstract to a scientific meeting, you can usually expect one of three outcomes.

I’ve listed them below in order of preference, plus the messages the meeting organizers and abstract reviewers are not-so-subtly sending you:

- Oral Presentation: Congratulations! Your abstract has been accepted for an Oral Presentation — in other words, the work sounds so fascinating, so potentially important, we’d love to hear more. You’ll give a 10-minute slide presentation in front of hundreds (maybe thousands) of colleagues on a big stage, backed by a larger than life video feed of your face on our giant LCD screen — so remember to pluck those errant facial hairs beforehand.

- Research Poster: Congratulations, your study has been accepted as a Research Poster! Now, you must generate a single-slide PowerPoint file packed with text, figures, and bullet points, have it professionally printed as a bed-sheet sized poster, and then affix it to a mobile bulletin board during the conference. We’ll give you a designated time to stand by your poster to explain the results. But don’t be alarmed when hundreds of other researchers and their posters line up as well in a vast, industrially lit space. And when we say vast, we’re not kidding — an Airbus A380 might roll by on its way to the runway.

- Rejection: We’re sorry, your study was too weak and/or uninteresting to meet our high standards. We’ll probably tell you that there were many competitive submissions, which is supposed to make you feel better. But you can come to the meeting anyway, providing you pay the registration and housing fees.

While the oral presentation is clearly the winner here, the research poster is undoubtedly the most challenging — and much more numerous, so everyone has to do one sooner or later. Several reasons why posters fill us with dread:

- How do I know what to include on the poster? More isn’t always better, but that lesson is lost on all of us while preparing posters. The default position? More is more. Many of these posters have so much text that they would exceed word-limits on actual submitted manuscripts, if not Victorian novels.

- How to get noticed? This large poster with tiny text is simply hard to read — personally made worse by the fact that I’m at that stage of eye “health” where everything is either too far away or too close. As a result, most meeting participants experience research posters as a blur of information as they walk by. It doesn’t help that further distractions abound in the poster hall, including chance encounters with colleagues, friends, and the occasional giraffe, elephant or other large mammal. I mentioned that the poster halls were vast, didn’t I?

- What’s the best way to convey the information to the (rare) person who stops by and actually wants to discuss your poster further? Here you need a good “elevator pitch,” but I always feel kind of like the weather person on the news show. “And over here [gesturing], we have both the multivariable analysis and the 7-day forecast. Don’t forget your umbrella for Tuesday!”

- What if you get a bad poster location? Did I convey the vastness of these interior spaces with the above reference to the Airbus A380? To the giraffe/elephant? If you’d prefer another reference, I recall a time my poster was positioned in the back corner of a cavernous hall, so far from everything that I’m convinced Lewis and Clark would have skipped this part of the country as too remote or forbidding for habitation. I stood there a long time, just me and my poster, tumbleweeds rolling by … hello? Can anyone hear me?

- What do you do with the poster after the meeting? Many young researchers wonder how to transport the thing after the meeting, which isn’t exactly airline-friendly in shape. After years of experience, I’ve finally figured it out: Unless you have a specific need for the poster already scheduled, say, “Thank you for your service,” Marie Kondo-style, and toss it in the recycling bin. Problem solved!

Not all is lost with research posters, however — it’s still better than a rejection, much better. After all, some of the most important research starts its academic life as a research poster. In our field, the most notable example is the first case of HIV cure after stem cell transplant. Yep — originally “just” a research poster! Maybe it was the sample size (n=1).

Now, how to fix them. The topic is much on my mind since I stumbled across the work of Mike Morrison, a Ph.D. student in psychology.

After I reached out to him, he was kind enough to share this “short version” of why he tackled the problem:

User Experience (UX) Designer quits career and starts a PhD in Organizational Psychology. Goes insane from how horrifically inefficient the user experience of science is. Has serious health scare. Suddenly gets real motivated to fix the problem and speed up science. Starts with the poster.

His brave plan for research posters puts the main message right in the center — and BIG! — with supporting information along the side. I’ve embedded the key figure from his method at the top of this post; he generously shares some templates here.

So if you’re a medical or scientific researcher, do yourself a favor and watch the brilliant and entertaining video. I’ve been thinking about it since seeing it last week, and have already shared it with some collaborators — and now with all of you.

And for your next scientific meeting — will you be brave enough to try it?

March 24th, 2019

Tetanus Case, No More MAC Prophylaxis, Playing in Dirt, and Low-Level Viremia — A National Puppy Day ID Link-O-Rama

In honor of spring (March 20), and the very important National Puppy Day (March 23), here are a bunch of ID and HIV-related recent items for consideration, contemplation, and perusal:

In honor of spring (March 20), and the very important National Puppy Day (March 23), here are a bunch of ID and HIV-related recent items for consideration, contemplation, and perusal:

- A life-threatening case of tetanus in an unvaccinated boy highlights the personal and financial cost of the anti-vaccine movement. How deeply embedded are these false beliefs? The parents still aren’t vaccinating their children.

- Prophylaxis for Mycobacterium avium complex is no longer recommended for people who start ART immediately, regardless of CD4 cell count. Have been advocating for this change long enough to write, “I told you so, nah nah.” Bet it takes a while to extract this from medical school curricula, where somehow MAC prophylaxis has assumed importance way beyond its actual usefulness.

- Travel advice about Zika has dramatically changed. This is a sensible policy shift — ongoing transmission is now exceedingly rare, even the regions hardest hit by Zika back in 2015-16. Still, the information may cause ongoing confusion — sensible discussion here.

- What is it like for an unvaccinated adult to get measles? This personal account makes it clear that it’s no picnic — measles is no mild “viral syndrome.” Once again, so impressive when people use their own adversity to try and effect change — thank you!

- And along a similar theme, thank you to this teenager who has publically sought vaccines for himself — even though his parents remain anti-vaxxers, and have publicly criticized him.

- ID consultation improves outcomes and saves money for people receiving outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT). From the abstract: “ID consultations during OPAT are associated with large and significant reductions in the rates of ED admission and hospital admission … as well as lower total healthcare spending.” Here’s a bold idea — let’s ask insurance companies and other payers to pay ID doctors for this important service, which right now is often done gratis!

- In community-acquired pneumonia, starting treatment that includes combination therapy directed at Pseudomonas aeruginosa is associated with higher mortality. Retrospective studies like this one can be tripped up by unmeasured confounders — such as whether those who received combination therapy were sicker in ways that could not be accounted for — but given the absence of data supporting combination therapy, here one must assume that less is more.

- Playing in the dirt improves the gut microbiome and reduces the risk of allergies. How’s that for prematurely drawing conclusions about the clinical implications of a mouse study? You’re welcome. Still — it wouldn’t surprise me a bit if it turns out to be true.

- Medical history buffs and antibiotic geeks will appreciate this detailed account about antibiotic development, bacterial resistance, and vancomycin. Even though it’s 240 pages (!) long, rest assured that the “font” is large, it’s double-spaced, and once you start reading, it’s hard to stop! I like this sentence about the 1950s: “The antibiotics aureomycin, terramycin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol formed the closely related group known as broad-spectrum antibiotics.” Ha. (H/T to Dr. David Aronoff for this find.)

- This sensible review finds no evidence that patients with sacral pressure ulcers need long-term treatment for underlying osteomyelitis. This does not mean withholding antibiotics from cases where there is evidence of acute infection (fever, purulent drainage, surrounding cellulitis), but is does mean that empiric 6 weeks of IV antibiotics for an equivocal MRI finding is of questionable value. A good read for everyone who does inpatient ID consults.

- These ID doctors argue that our specialty should have a voice in the “This Is Our Lane” movement to reduce gun violence in our country. Certainly survivors of gun violence frequently have numerous infectious complications, especially those with spinal cord injuries. That the authors come from Louisiana — a state with a particularly high rate of firearm related deaths — adds to the importance of their message.

- A couple of additional studies add to the the evidence that persistent low-level viremia in HIV may mean something clinically — but we still don’t know what to do about it. In this paper, 50-199 was associated with subsequent failure; in this one, the problem level didn’t kick in until > 200. I’m convinced that for those that are 100% adherent to meds, it doesn’t mean much; for those that have low-level viremia due to irregular adherence, it does! For more on this topic:

- Here’s a new explanation for detectable HIV in patients on suppressive therapy — “repliclones”. These are large cell clones carrying intact proviruses, and don’t represent replication in the traditional sense — but can contribute to low-level detectable virus. (The RRR™ of CROI 2019 was two weeks ago; I should have highlighted this study.) A good further description of the study is here, along with what it means for cure research.

- This politician takes his kids to chicken pox parties, and this one believes that antibiotics work against measles. Hmmm … trying to think of something funny to write, but words completely escape me. And that’s rare.

- A second-year medical resident put together this informative and entertaining “Tweetorial” on MRSA precautions. Should be required reading for any institution considering the need for contact precautions for this organism. Wondering if he’s going into ID, seems like a natural!

Because this tweet seemed to strike a nerve among so many;.

Suppose its #tweetorial time to evaluate the evidence supporting, or not, the use of contact precautions (CP) to prevent the transmission and infectious complications of #MRSA https://t.co/BdwLxvQ4f6

— R Logan Jones, MD FACP (@rloganjonesmd) February 5, 2019

- We hear a ton about overtreatment of bacteriuria in the elderly, but might we sometimes be undertreating them? The study found no antibiotic therapy for UTIs was associated with a significant increase in bloodstream infection and all-cause mortality. The paper has already stirred up extensive controversy among antibiotic stewardship-types, not surprisingly.

- And in case you’re wondering, yes there are new guidelines for management of asymptomatic bacteriuria. To those who don’t practice medicine, let me assure you — this is not always an easy assessment to make, especially in the elderly in particular those with cognitive impairment! It’s still not quite clear what we should do with worsening incontinence, or when patients only note cloudy or “bad smelling” urine — a limitation acknowledged in the paper.

- Think of infection with Mycoplasma hominis and (in particular) Ureaplasma urealyticum in immunocompromised patients with unexplained hyperammonemia. That these organisms are so difficult to culture and also harbor unpredictable resistance patterns makes diagnosis and management tricky.

- ID has significant disparities in academic achievement and faculty rank by sex. Fascinating paper by one of our fellows (Dr. Jennifer Manne-Goehler), with perhaps the most interesting part being that the disparity is greater in ID than cardiology — why might that be? It is particularly important to understand these disparities in ID since women account for more than 50% of those entering our field.

- Rabies prophylaxis after a cat bite can cost you a lot. There’s nothing wrong with the medical management here; it’s the way our very peculiar healthcare system adjudicates the cost of care. In this example, a woman received a bill for $48,512 after a two-hour visit to an emergency room, which included shots of rabies immune globulin plus the vaccine, and a dose of an antibiotic. “My funeral would have been cheaper,” she said.

- United HealthCare is offering patients two $250 prepaid debit cards every 6 months to “offset medical expenses” if they go on certain less expensive HIV regimens. Consider this the converse of the “co-pay cards” provided by the pharmaceutical industry for brand-name drugs. The main problem I have with these programs is lack of transparency — here, what is United HealthCare making off this deal? Odds are it’s more than the cost of those debit cards, especially if those cards are used for services provided by United HealthCare anyway. Further information on this program from IDSA’s perspective is here,

- On the topic of drug costs, here’s authoritative and interesting review of drug pricing in ID. All the favorites are covered, from the shocking HCV drug prices to the mind-boggling pricing of generics such as pyrimethamine, albendazole, and even penicillin. The senior author is my long-time friend and colleague Dr. Rochelle Walensky — who appears to be far less cynical about that United HealthCare plan than I am!

- If you want a quick update on investigational antifungal agents, start right here with this summary. Wow, that’s quite a pipeline! And thank you, Dr. Andrej Spec (@FungalDoc), who was rewarded for this great work by receiving a commission (from me) for a full review paper.

- San Francisco has a poop on the streets problem. And no, it’s not just dogs and puppies — it’s also human feces on the street, the result of stark disparities of wealth readily apparent when walking around that city. From the piece: “An infectious-disease specialist … has compared certain parts of San Francisco—where contaminants include a proliferation of discarded needles—to slums he’s studied in the developing world. The slums were cleaner.” Thanks to Dr. Monica Gandhi for first alerting me to this problem!

Too bad it’s another year until National Puppy Day returns.

Until then, enjoy this:

March 18th, 2019

Just 1 Month of TB Preventive Therapy Works for People with HIV in TB-Endemic Regions — How About Other People in Other Places?

There’s a look our patients frequently give us when we tell them that preventive therapy for tuberculosis involves 9 months of treatment. If I were to put that look into words, they would be:

There’s a look our patients frequently give us when we tell them that preventive therapy for tuberculosis involves 9 months of treatment. If I were to put that look into words, they would be:

Yikes, Doc, 9 months is waaay too long — you must be out of your mind.

It’s the “9 months?!?!” face. We’ve all seen it.

Even the recent shift to using the 4-month rifampin strategy has been met with only partial relief, though I acknowledge it’s better. And the weekly isoniazid/rifapentine for 12 weeks approach hasn’t gained much traction in our clinic, possibly because some still believe that it must involve directly observed therapy.

This is why the clinical trial of TB prevention just published in the New England Journal of Medicine is so important. Tuberculosis remains the leading infectious cause of death in the world. Easier preventive strategies are urgently needed.

Nicknamed BRIEF-TB, the study compared a 1-month — you read that right, just 1 month — regimen of daily isoniazid (INH) and rifapentine to the standard-of-care, 9-months of INH. The primary endpoint was active TB or death. Eligible participants had HIV and were living in high TB prevalence areas, or had latent TB diagnosed through either a positive tuberculin skin test (TST) or a reactive interferon gamma release assay (IGRA). Roughly 3000 people entered the study.

After a median of over 3 years of follow-up, the 1-month strategy was noninferior to 9 months, with the incidence of active TB or death comparably low in both arms. Not surprisingly, the 1-month group completed therapy significantly more often than the 9-month group; toxicity was also less frequent, though this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Big news — this strategy could really change clinical practice, at least for people with HIV and especially in high prevalence regions.

But how do these data apply to those of us in areas of low TB prevalence, or to people without HIV, or both? Those are key questions.

On the one hand, if it works in regions with high TB incidence and in people with HIV, it should work in people here — where TB is much less common, and where we frequently prescribe preventive therapy even for people with normal immune status.

However, here are a couple of reasons to be cautious before making this extrapolation.

Essentially all the people we treat here for latent TB have positive TSTs or IGRAs. In the BRIEF-TB study, those with positive tests for latent TB comprised only 23% of the study entrants; in the remainder it was either not done or negative. While it’s true that these tests are notoriously insensitive in HIV, if a substantial proportion of the remaining 77% didn’t have latent TB at all, this could skew the results to showing no difference between arms.

Plus, most of the study participants received antiretroviral therapy. HIV therapy on its own reduces TB incidence even without preventive therapy. For people without HIV, sometimes we’re motivated to give preventive therapy for the very opposite reason — they are on, or about to start immunosuppressive treatment.

So for now, consider this an open question, an unknown that is unlikely to be answered in a comparable clinical trial done in people without HIV — at least if my clinicaltrials.gov search and consultation with TB experts is correct.

But take the poll anyway.

March 10th, 2019

Really Rapid Review — CROI 2019 Seattle

As a foot of wet snow bore down on Boston last week — see this post for why that matters — HIV researchers and policy makers headed to Seattle for this year’s Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, or CROI, which took place from March 4-7.

And already I was feeling the pressure, based on this one little nudge:

Looking forward to reading @PaulSaxMD Rapid review of #CROI2019

— Aishalton (@aishalton) March 3, 2019

OK, @Aishalton, here you go with some of the highlights. And it’s not just a rapid review, but a Really Rapid Review®!

I can never cover everything, so to all brilliant readers — please use the comments section for things I’ve missed, general comments, and questions.

- Tony Fauci led off the conference with the plan to eliminate HIV in the United States. Scientifically, it’s not rocket science or brain surgery — get enough people with HIV on treatment and those at risk on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and incidence will fall, as it has in San Francisco, New York, Australia, London, and other regions with high ART and PrEP coverage. But the big challenge in our great big and highly diverse country is that those hardest-hit with HIV — poor, minority populations, especially in the South — are exactly those with less access to medical care. Medicaid expansion, anyone? Tossing my slight skepticism aside, I noted that Dr. Fauci was genuinely excited about having all the various government groups behind it, which should eliminate some barriers. And he didn’t mention the President by name even once, proving he knows his audience!

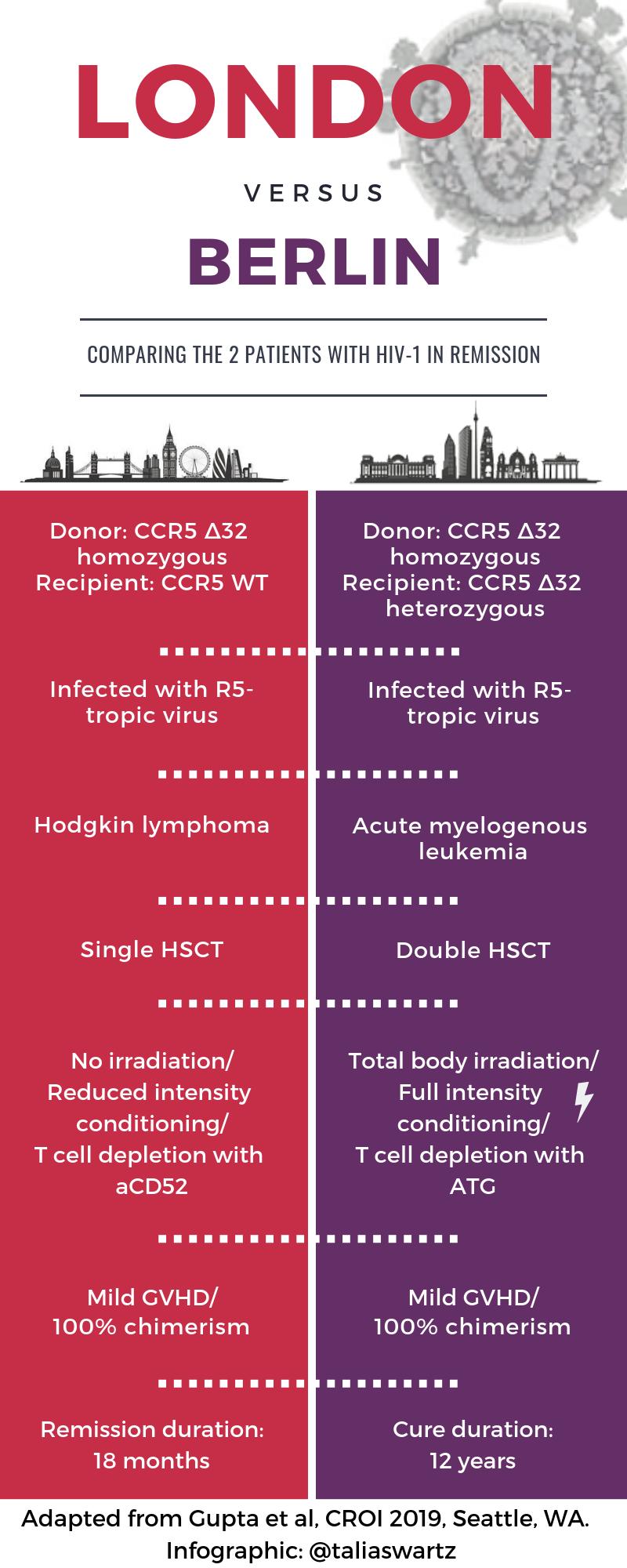

- A second person has been “cured” of HIV after receiving a stem cell transplant from a donor with the CCR5 delta 32 mutation [29]. You might have heard something about this case, ha ha ha. The transplant took place in London in a patient with refractory Hodgkin’s disease, and I put the word “cure” in quotes since there have been previous long-term remissions that weren’t durable (Mississippi Baby, Boston transplant patients). Note the important differences from the prior “Berlin” case — see awesome graphic courtesy Dr. Talia Swartz. And no, it’s still not a viable strategy for broader application, for clear reasons nicely articulated in this piece by Gregg Gonsalves — but an n of 2 is 100% better than an n of 1!

- But could it be an n of 3 [394]? This patient from Düsseldorf (why are all these cases in Europe?) has been off treatment since November 2018 — stay tuned. Remember, other stem cell transplants from CCR5-negative donors have not achieved remission, such as this notable example.

- For HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, TAF/FTC was noninferior to TDF/FTC [104]. Despite high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the study population, demonstrating ongoing potentially high-risk contacts, the incidence of HIV infection in this large study was much lower than expected. Hence, the results met the noninferiority threshold only because there were numerically fewer infections in the TAF/FTC vs. TDF/FTC group (7 vs. 15). Concerns about low incidence notwithstanding, the results argue that TAF/FTC is at least not too much worse (“noninferior” in English) in preventing HIV than TDF/FTC. In my opinion, it would now be preferred if there is pre-existing renal or bone disease.

- An electronic medical record algorithm can identify the best candidates for PrEP [105]. It is unrealistic to expect primary care clinicians to consider PrEP for all the patients in their panel, as the vast majority are not at high enough risk for acquiring HIV. In this study from Kaiser California, the top 1% HIV risk score generated by the EMR algorithm identified over 6000 candidates — with 92% not receiving PrEP. Seems like an excellent strategy to bring PrEP to those who need it the most.

- Among over 1437 people attending a New York City sexual health clinic, 97% started PrEP immediately after a clinical screen for acute HIV, hepatitis B, or impaired renal function [962]. The only test back before starting PrEP was a negative rapid HIV test. The study is part a laudable effort in New York to reduce barriers to PrEP initiation.

- In Atlanta, young black MSM who started PrEP had a high likelihood of stopping [963]. Roughly 125 started PrEP in a dedicated program for this patient population. During 720 days of follow-up, 63% stopped at least once, and 31% stopped completely.

- Out of 3685 patients newly diagnosed with HIV over a 2-year period in NYC, only 91 (2%) had been PrEP users — and nearly a third of them had the M184V mutation [107]. No K65R mutations were detected. By contrast, M184V was found in 2% of those who never used PrEP. Remarkably, only 75% of those who acquired HIV on PrEP had baseline genotypes! Seems like taking PrEP and then getting HIV infection is an emphatically good indication for clinicians to obtain resistance testing.

- A randomized population-based effort to provide ART to highly prevalent communities in Southern Africa reduced HIV incidence, but not in all study arms [92]. The trial, called POPART, randomized populations to standard-of-care, universal ART, or ART provided based on CD4 thresholds (initially 350, then 500, then universal). Surprisingly, only the last of these significantly reduced incidence. The results imply that even with 90-90-90 targets met, there is sufficient ongoing transmission that treatment alone is unlikely to end the epidemic in our highest prevalence areas.

- In patients with long-term viral suppression and no resistance, monthly, long-acting, injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine was noninferior to continued oral therapy [139]. The median time of suppression prior to switch was 4 years. Only 1.6% and 1.0% had viral loads >50 at week 48 in the injectable and oral therapy arms, respectively. Injection-site reactions were common, but mostly mild. Patient satisfaction scores for the injectable strategy were off-the-charts favorable. (FYI, the study is called ATLAS, which I’m sure stands for something clever.)

- After treatment-naive patients started treatment with ABC/3TC/DTG for 20 weeks and achieved viral suppression, monthly, long-acting, injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine was noninferior to continued ABC/3TC/DTG [140]. In this second study (called FLAIR), 2.1% and 2.5% had week 48 viral loads >50 in the injectable and ABC/3TC/DTG arms, respectively, at week 48. The tolerability of the injections and the treatment satisfaction scores? Again, excellent.

- In both ATLAS and FLAIR, a small number of participants failed the injectable therapy with emergent drug resistance despite adhering to study visits. Three such cases occurred in each study. For reasons that are still unclear (at least to me), 5/6 were enrolled in Russia, and all 5 harbored HIV subtype A1. In the FLAIR study, two patients developed the Q148R integrase-resistance mutation. Drug levels in all these participants were in the lower end of the distribution, but well within the range in which other study subjects maintained suppression. A mystery! Webcasts here and here.

- In treatment-experienced patients failing first-line therapy with 2 NRTIs/1 NNRTI, dolutegravir (+ NRTIs) is superior to lopinavir/r (+ NRTIs) regardless of baseline NRTI resistance [144]. Important, confirmatory results, with the full study recently published here. Based on the study design (which mandated that all study participants receive at least one genotypically active NRTI), the results cannot tell us the preferred NRTI combination to use with the baseline K65R plus M184V mutations — which didn’t stop me from asking about this after the presentation. I thought perhaps after looking at all those genotype results, the answer would magically emerge to the investigators!

- Transmitted drug resistance in the USA remains essentially stable [526]. The key percentages resistant by class: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) (11.9%), nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) (6.8%), protease inhibitors (PIs) (4.3%), and INSTIs (0.8%). These numbers represent small increases in NNRTI and INSTI resistance, but at this point hardly enough to change practice. (Hey, did you know that the CDC does these studies off of resistance genotypes that are ordered in clinical care and then forwarded to them? Seems like something that should be done with a more representative and population-based approach.)

- Providing viral load results during clinic visits significantly improved viral suppression and retention in care [53LB]. Investigators in South Africa randomized 390 people at their month 6 follow-up visit after starting ART to point-of-care viral load results (given to patients at their visit) or usual lab-based testing. Twelve months later, viral suppression was observed in 89.7% of the point-of-care group, vs 75.9% in the standard of care arm, a whopping 14% difference. If there were differences this profound in a clinical trial comparing HIV treatments, a DSMB would stop the study early!

- Several studies implicated integrase inhibitors (INSTIs) as treatment-related contributors to excess weight gain. Abstracts 669 (switch), 670 (initiation), and 672 (switch in women) all found a positive signal; abstract 671 (switch) did not, once controlling for other factors. (And weight gain is the very definition of multifactorial!) Neither did cabotegravir in a small study of people without HIV [34]. However, since a randomized clinical trial of switching from PI-based to DTG-based regimen demonstrated significant weight gain with the switch, this association with INSTIs appears to be causal.

- Baseline NRTI resistance did not influence viral suppression in patients successfully treated with tenofovir/FTC plus DTG if they were randomized to switch to bictegravir/FTC/TAF [551]. This is an interim analysis of an ongoing clinical trial, suggesting that as with treatment-naive patients and those switching with no resistance, DTG and BIC-based regimens are very similar. Note that “archive” DNA resistance testing identified resistance mutations not seen on historical genotypes; the opposite also occurred. Hmmm … wonder which is the gold standard?

- An investigational capsid inhibitor provided potentially therapeutic drug levels for 12 weeks after a single subcutaneous injection [141]. Phase 1 studies in people with HIV have begun. Key for this long-acting, potent agent (GS-6207) will be to find an appropriate partner drug.

- A single infusion of a broadly neutralizing antibody (bNAb) PGT121 sustained viral control for 6 months in two patients with low baseline viral loads [145]. By contrast, among the nine treated participants with viral loads higher than 3.3 log, four of nine did not respond at all. Several other presentations about bNAbs at the conference (here and here, for example), but this line of therapy is still in its infancy. (Two questions — does some savant know the names all of these bNAbs? Why isn’t “bNAb” spelled “BNAb,” with the “B” capitalized?)

- More studies aiming to improve the abnormal inflammatory or heightened immune activation status of people with HIV demonstrated no clear benefits. For the record, the interventions at this CROI included sirolimus, probiotics, and ruxolitinib. Hey folks — the immune system is complicated! It would not surprise me if further interventions in this area are limited to those treatments that would be indicated otherwise — e.g., statins for reducing cardiovascular disease.

- Opioid-overdose deaths among people with HIV have significantly increased since 2011 [147]. The increase has occurred in all transmission groups, not only those who acquired HIV via injection drugs.

- Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir successfully treated HCV in a small number of pregnant women [87]. Only 8 women were eligible; 10 potential participants were excluded due to genotype 2 or 3 infection. All had acquired HCV from injection drug use. The results suggest the next study should be with velpatasvir/sofosbuvir or glecaprevir/pibrentasvir — and also point to the huge data gap of HCV treatment in this population, as this is the only prospective study in pregnancy to date!

- Women late in pregnancy (>28 weeks gestation) and not on ART experienced a significantly shorter time to viral suppression when randomized to DTG vs EFV-based regimens [40]. Roughly 74% in the DTG arm and 43% in the EFV arm had viral loads <50 at delivery, a highly significant difference. These results appear to favor DTG, with two caveats that

might not be drug related — three HIV transmissions and four stillbirths occurred, all in the DTG arm. Transmissions were believed to be in utero transmissions — remember that starting ART late in pregnancy is associated with a 7-fold increased risk of maternal-to-child transmission, and a doubling of infant mortality in the first year. Name of this study? DolPHIN-2 (DOLutegravir in Pregnant HIV Mothers and TheIr Neonates) — and not to be confused with DolPHIN1— or the next study.

might not be drug related — three HIV transmissions and four stillbirths occurred, all in the DTG arm. Transmissions were believed to be in utero transmissions — remember that starting ART late in pregnancy is associated with a 7-fold increased risk of maternal-to-child transmission, and a doubling of infant mortality in the first year. Name of this study? DolPHIN-2 (DOLutegravir in Pregnant HIV Mothers and TheIr Neonates) — and not to be confused with DolPHIN1— or the next study. - Dolutegravir levels were reduced when given with preventive therapy of weekly isoniazid and rifapentine, but not enough to warrant dose adjustment [80]. Viral suppression was maintained, with no significant adverse events. Importantly, for treatment of TB (with daily rifampin), dolutegravir dosing should be changed to 50 mg twice daily. Name of this study? Also “DOLPHIN”, for DOLutegravir, rifaPentine, INH, INvestigation. (Notice how I put those together — clever, eh? And what are the chances of a single CROI having two completely unrelated HIV-related studies named “DOLPHIN”?)

- Cannabis appeared to improve blood brain barrier injury and CNS inflammation [459]. Of course it did! We were in Seattle, remember? And that’s not a skunk you’re smelling.

Look, even though your Netflix beckons, if you have a few moments, the following webcasts by experts on diverse topics are must watch for any HIV/ID specialist. I’m listing below my favorites, with the caveat that I couldn’t see all the talks and might have missed some other gem:

- David Back on Pharmacology and Drug Interactions

- Jeanne Marrazzo on STIs

- Irini Sereti on Inflammation

- Jean-Michel Molina on PrEP Challenges

- Laura Waters on Two-Drug Therapy

So, what did I miss? Let me have it.