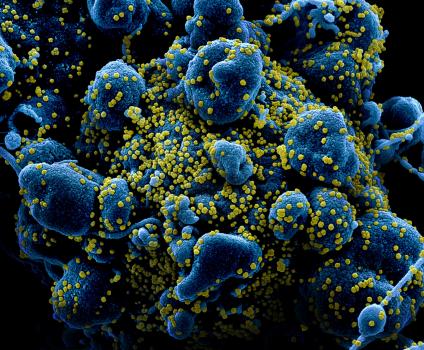

An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

June 28th, 2020

Is COVID-19 Different in People with HIV?

From the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, one of most common questions I’ve received has been whether COVID-19 has different clinical manifestations in people with HIV.

Would it be more lethal since people with HIV have impaired immune systems? Or milder since some of the damage in severe cases is immunologically mediated?

Or would it be similar, since antiretroviral therapy (ART) is so effective?

Or maybe people with HIV are protected, as they are already taking antiviral medications — some of which (in particular the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, NRTIs) have activity against SARS-CoV-2 in experimental systems.

The honest answer, as it has been for so much of this new disease, is that we don’t know definitively — but the early evidence from small studies suggested COVID-19 was quite similar in those with and without HIV.

This passed the anecdotal test too. Here in Boston, all of us HIV/ID specialists have had patients with HIV develop COVID-19. Absent other medical problems known to be associated with poor outcome, they mostly did fine.

What we need, of course, are larger, well-conducted cohort studies to confirm these impressions. And those are just starting to appear.

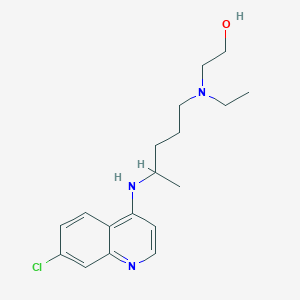

In the Annals of Internal Medicine, Spanish researchers describe the incidence of COVID-19 among 77,590 HIV-positive persons receiving ART, looking also at their risk of hospitalization. They primarily focused on their antiretroviral therapy — in particular, the NRTIs.

During a 3-month period, 236 people with HIV were diagnosed with COVID-19, and 151 were hospitalized. The risk of hospitalization by NRTI treatment per 10,000 patients was lowest for TDF/FTC (10.5), while other NRTI strategies were similar (TAF/FTC 20.3, ABC/3TC 23.4, single or no NRTI 20.0). None of those on TDF/FTC died or were admitted to the ICU. The group receiving TDF/FTC also had a lower overall incidence of infection.

What might explain this apparent protective effect of TDF/FTC? As noted above, and further elaborated upon in the paper’s discussion section, NRTIs demonstrate in vitro antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2; furthermore, tenofovir may have beneficial immunomodulatory effects. The higher plasma and extracellular concentrations of tenofovir DF over tenofovir AF could explain the differences between the two.

But before we leap to that conclusion, remember that similar in vitro observations exist for numerous anti-infective compounds, from A-Z and beyond. (Remember hydroxychloroquine? Oh yeah, that was a thing.) Citing these mechanistic explanations hardly proves that they do anything in human beings.

And of course the people remaining on TDF/FTC today are least likely to have many of the medical comorbidities associated with worse outcome in COVID-19 — they’re healthier at baseline. Most older people with HIV, in particular those with renal or cardiovascular disease, now receive either TAF/FTC, or increasingly, a regimen that does not include either tenofovir or abacavir. The paper does not include data on these factors.

So consider the data from this fascinating paper to be hypothesis-generating rather than conclusive — as readily acknowledged by my long-time friend and HIV/ID colleague from Spain, Dr. Jose Arribas, also a co-author on the study.

We await confirmatory observations elsewhere, perhaps in people currently taking TDF/FTC for HIV PrEP — could it amazingly also be preventing a second viral infection? — or even better, from the results of a pre-exposure prophylaxis randomized study, now ongoing.

Of course these data about the NRTIs don’t get at the original question posed at the start of this post — do people with HIV who get COVID-19 do better, worse, or the same as those without HIV?

Tucked away in the discussion section is this sentence:

In line with the greater all-cause mortality of HIV-positive persons compared with the general Spanish population, we found greater age- and sex-standardized mortality from COVID-19 in HIV-positive persons (3.7 per 10 000 compared) than in the general population (2.1 per 10 000).

A large South African study, furthermore, recently reported the following:

Large study of clinical outcomes of #COVID19 in South Africa demonstrates HIV associated with increased risk of death. Effect has not been seen in smaller European, USA cohorts thus far. No diff by viral suppression. H/T @AntonPozniak https://t.co/TXwlJzsOnQ pic.twitter.com/FUxz5J7Aog

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) June 17, 2020

The linked slide presentation contains scant data about the HIV population — only that this effect was seen in both those with and without HIV viral suppression. Apparently we’ll hear more at the 23rd International AIDS Conference in July.

So what can explain these apparently negative outcomes of COVID-19 in people with HIV, both in Spain and South Africa?

In Spain and other developed countries, I’m betting on comorbidities — hinted at by the senior author of the Spanish study.

A significant fraction of our older HIV population endured years of uncontrolled viremia, immunosuppression, and toxic ART. This group experiences excess non-HIV medical problems comparable to HIV-negative people who are 5-10 years older. Many of these issues are well-defined risk factors for severe COVID-19, and perhaps controlling for these conditions will yield a prognosis comparable to those without HIV.

For South Africa, additionally, people with HIV tend to come from much more socially disadvantaged backgrounds — it is strongly associated with poverty and lack of access to care, also negative predictive markers in COVID-19 worldwide.

So while data from these larger studies are welcome, we eagerly await more. And in the meantime, we can contemplate what all the acronyms stand for in the alphabet soup that is Jose’s twitter profile.

June 21st, 2020

Dexamethasone Improves Survival in COVID-19 — Why This Should Be Practice Changing Even Before the Paper is Published

When the news broke last week that the dexamethasone component of the RECOVERY randomized clinical trial was halted because those receiving the drug were significantly more likely to survive, I posted the following:

– Very welcome news, dex is cheap, widely available!

– Demonstrates the power of RCTs vs obs studies, which were conflicting

– How will the numerous ongoing studies of immunomodulators be modified?

– Rx guidelines — act now or wait for more info?https://t.co/qBsaZ1csH2— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) June 16, 2020

Note my last point, about “guidelines”. These committees have a responsibility to get what they recommend right, and might be slower than clinicians to recommend an intervention with limited information — even if it is potentially life-saving.

But my assumption was that clinical practice would change quickly, awaiting the updating of guidelines. After all, this is what we’ve been waiting for — data from a randomized trial demonstrating a clear benefit. Even better, it’s a readily available, inexpensive strategy — a course of corticosteroids — familiar to us all.

I confess the responses to my post, and comments elsewhere, surprised me. Lots of skepticism. Wow.

The comments fell into several interrelated categories:

Let’s wait for the study to be peer-reviewed and published in an established medical journal before changing clinical practice.

Really? Even when the sickest patients — those requiring oxygen or ventilatory support — were more likely to survive?

(Yes, I keep italicizing that endpoint. Emphasis, you know.)

For the record, here are the results:

Dexamethasone reduced deaths by one-third in ventilated patients (rate ratio 0.65 [95% confidence interval 0.48 to 0.88]; p=0.0003) and by one fifth in other patients receiving oxygen only (0.80 [0.67 to 0.96]; p=0.0021).

When a study stops because of a survival benefit for a life-threatening disease, take note. It’s because continuing the study as originally designed is unethical — those randomized to receive “usual care” would be deprived of a potentially life-saving treatment.

The steering committee has a responsibility of ensuring the safety of trial participants. And remember, they have access to all the study data, even if we don’t.

It’s critical that this information be made available as soon as possible. Patients are being treated today who might benefit, and writing papers and subsequent peer review take time — typically weeks, even with the “warp speed” of COVID-19.

To quote one of the investigators: “Dexamethasone is inexpensive, on the shelf, and can be used immediately to save lives worldwide.”

Well said.

Why are we getting critical information via press release? I’m inherently distrustful. A press release doesn’t represent actual data.

It’s reasonable to be skeptical of clinical trial press releases, especially when issued by private pharmaceutical companies with multi-million dollar marketing divisions.

These notoriously exaggerate the importance of study results, especially when focused on surrogate markers of disease that may or may not predict clinical outcome.

But consider — this isn’t a press release by a giant company, citing a minor change in an inflammatory cytokine or quality-of-life metric in an open-label study. It’s a respected clinical trials group, funded by the government of Great Britain, and they are reporting a survival benefit from their clinical trial.

To their credit, they early on started doing randomized trials of various COVID-19 interventions while the rest of the globe practiced the therapeutic equivalent of throwing drugs against the wall hoping some of them would stick.

Lopinavir-ritonavir! Interferons! Oseltamivir! Hydroxychloroquine! Azithromycin! Ivermectin!

And it’s not just antimicrobials — virtually every immunomodulator under the sun, some extremely expensive, has found its way to off-label use for critically ill patients with COVID-19. Tocilizumab! Sarilumab! Anakinra! Ruxolitinib! Eculizumab! Any-other-mab! And more …

Yes, it’s hard to keep up — see Table 1 in this recent review for all the various anti-inflammatory approaches tried off-label, with many of these now under study.

If we’re using some of these unproven therapies — and many of us have — why not dexamethasone, which in the RECOVERY trial improved survival?

Here we go again! Haven’t we been burned already multiple times with research on COVID-19, only later to have this information questioned, or retracted?

Quite reasonable to be cautious in this very fast-moving area.

But the infamous research that has “burned” us involved much weaker levels of evidence — little more than anecdotal observations at one extreme and observational studies with likely falsified data at the other.

None has been a randomized clinical trial with a survival benefit.

(Have I noted that result enough times already? Nah.)

I need more details about the study. What were the primary endpoints? The specifics of the intervention? What were the patient characteristics of those enrolled? Did some subgroups benefit more than others? What were the toxicities?

All very reasonable questions! But good news — we have the full protocol available for review. This can answer some of these queries, including the endpoints and description of the exact interventions studied.

It’s a highly valuable document that may allay some concerns that the investigators somehow didn’t conduct the study or analyze the data properly.

And I share the interest in seeing the fully published paper to examine the study results in more detail.

But until it is published, we have now highly favorable results in the most important clinical endpoint in any interventional study — improved survival.

So aside from those patients for whom corticosteroids would be contraindicated, it’s hard to imagine not offering dexamethasone — today — to a person with COVID-19 that requires supplemental oxygen or ventilatory support. They might live longer!

And that’s good news.

Just like getting a fresh video from the sporting archives of Olive and Mabel.

[Originally this post cited the action of a Data Safety Monitoring Board; rather the study Steering Committee assessed that enough patients had been enrolled to answer the question of whether dexamethasone provides benefit. Have modified to reflect this difference.]

June 7th, 2020

Hydroxychloroquine Not Effective in Preventing COVID-19 — In Praise of a Negative Clinical Trial

The headlines might read, Malaria Drug Ineffective in Preventing COVID-19 — but that doesn’t do justice to a remarkable clinical trial, just published this week in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Led by Dr. David Boulware at the University of Minnesota, the study asked this question: Does hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) prevent the development of COVID-19 in people after significant healthcare or household exposure to the disease?

To say that the recruitment of this post-exposure prophylaxis trial was innovative hardly gives the methods enough credit. I first heard about the study in mid-March, based on this post by the lead author:

Healthcare worker exposed to COVID-19? Sharing a home with someone with COVID-19? Our Univ. of Minnesota team at the has launched a clinical trial studying a drug that may help prevent infection in those exposed to coronavirus. Email us at covid19@umn.edu to enroll.#IDTwitter pic.twitter.com/eFa425j2Z5

— David Boulware, MD MPH (@boulware_dr) March 17, 2020

It wasn’t long after reading this that I received a frantic message from one of my long-term patients with just this sort of high-risk exposure. I immediately referred him to the study.

With this study design, he didn’t have to fly to Minnesota to enroll — it was all done remotely. Informed consent, medication dispensing and shipment, adverse event monitoring, endpoint assessments.

(He did fine, by the way.)

In essence, this randomized, placebo-controlled study gives new meaning to the phrase “multicenter clinical trial”! I count 821 “centers” — specifically, the homes of the 821 participants, 414 of whom received HCQ, 407 placebo.

As the authors note, the conduct of the study had major advantages:

This approach allowed for recruitment across North America, minimized the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection to researchers, lowered the burden of research participation, and provided a timely answer to this question of whether postexposure prophylaxis was effective. Moreover, this approach allowed broad geographic participation regardless of anyone’s physical distance from academic centers, increasing the generalizability of the findings.

Think also of the countless time, money, and effort saved by avoiding the need for local institutional review board approvals, clinical trials contracts, and study visits. Remarkable.

No, this isn’t the first study to enroll and follow participants remotely — the groundbreaking Physicians‘ and Nurses’ Health Studies come to mind. But it’s certainly the first one conducted and completed during a global pandemic.

For the record, the incidence of clinical COVID-19 illness did not differ significantly between groups (11.8% for HCQ, 14.3% placebo), and people receiving HCQ had more side effects, mostly gastrointestinal. There were no serious cardiac adverse events, a problem reported on other studies (especially when combined with azithromycin).

As noted in the accompanying editorial (and acknowledged by the authors), the study had several limitations, most notably the small proportion of COVID-19 cases (just over 10%) confirmed by PCR, and the delay (3 or more days) between exposure and starting preventive treatment. Furthermore, such a remotely conducted study cannot collect highly detailed data.

These and other limitations mean that these results may not be definitive; other prevention studies with HCQ continue.

Still, kudos to the investigators for so quickly carrying out this remarkable study. It’s a reminder that sometimes the innovation in clinical trials comes in the methods section, not in the results.

May 31st, 2020

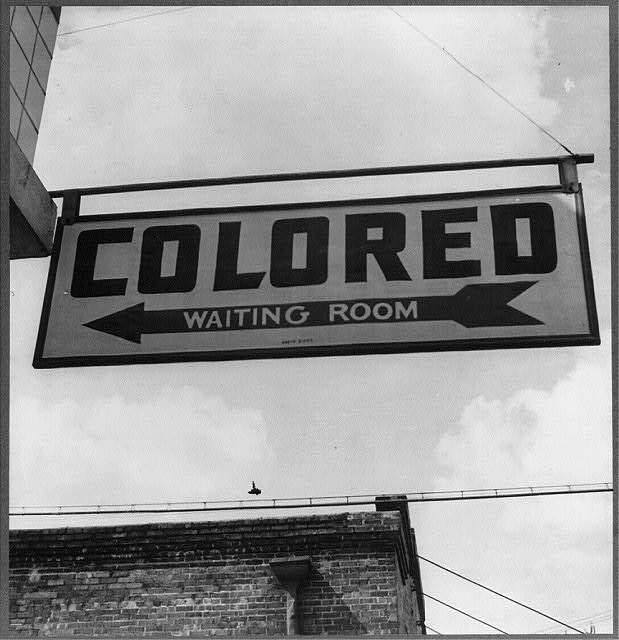

America the Not So Beautiful Right Now, with a Must-Read Book Suggestion

Have you read W. Kamau Bell’s The Awkward Thoughts of W. Kamau Bell: Tales of a 6′ 4″, African American, Heterosexual, Cisgender, Left-Leaning, Asthmatic, Black and Proud Blerd, Mama’s Boy, Dad, and Stand-Up Comedian?

If you haven’t, may I suggest you put it at the top of your list, and pronto? In addition to being funny, moving, and thought-provoking, it’s one of the most influential books I’ve read in the past decade — and could not be more relevant now.

And by influential, I mean influential to me — a white guy living in the United States, and therefore generally oblivious to the terrifying racism blacks experience here on a regular basis.

So probably influential to anyone who hasn’t experienced what he describes in this brilliant book. It acts as a great antidote to our complacent cluelessness.

There’s a chapter I’ve thought about so many times since, especially this week. It’s called, “Awkward Thoughts about Being a Black Male, Six Foot Four Inches Tall in America”.

Here’s how the chapter starts — apologies for the lengthy quote, please read to the end:

I am afraid of the cops. Absolutely petrified of the cops. Now understand, I’ve never been arrested or held for questioning. I’ve never been told that I “fit the description.” But that doesn’t change a thing. I am afraid of cops the way that spiders are afraid of boots. You’re walking along, minding your own business, and SQUISH! You’re dead. Simply put, I am afraid of the cops because I am Black. To raise the stakes even further, I am male. And to go all in on this pot of fear, I am six foot four and weigh 250 pounds . . . at least. (I stopped keeping track, which is the next best thing to actually working out.) Michael Brown, the unarmed Ferguson, Missouri, eighteen-year-old shot dead by police in the summer of 2014 , was also six foot four. Eric Garner, who was strangled to death by the NYPD, was six foot three. Depending on your perspective, I could be described as a “gentle giant,” the way that teachers described Brown and the way that friends described Eric Garner. Or I could be described as a “demon,” the way that Officer Darren Wilson described Michael Brown in his grand jury testimony. And just like Eric Garner, I have asthma, so when I hear him say on video, “I can’t breathe,” as the officer chokes the life out of him for selling loose cigarettes, I can feel it in my chest as I’m sure he did.

Oh that last sentence — so chilling. Written in 2017, in case you were wondering.

Some readers might wonder why I’m covering this topic today here on an ID blog. Some might suggest I stick to medical topics, say they don’t come here for this kind of commentary, accuse me of “virtue signaling”.

To them I say — feel free not to read this. No one’s forcing you.

And imagine if I didn’t comment. So much worse — unbearably so, at least for me. Our country’s history of racism is so long and painful the problem will only improve if we all fight it together.

Meanwhile, if you can’t stand a post without ID, how about this from super ID fellow Dr. Aaron Richterman, commenting on the staggeringly disproportionate toll COVID-19 has taken on people of color?

Remarkable that this paper in @NEJM alludes to genetic differences but doesn't mention the word "racism" one time.https://t.co/SetGVpnfU1

— Aaron Richterman, MD (@AaronRichterman) May 27, 2020

Highly relevant.

May 25th, 2020

A Major Advance in Non-COVID-19 ID Research You Might Have Missed

One thing about the COVID-19 pandemic — other important non-COVID ID news gets crowded out.

One thing about the COVID-19 pandemic — other important non-COVID ID news gets crowded out.

As a prime example, take HPTN 083, a major clinical trial in HIV prevention. The results are a big deal, and should have garnered more attention when they were released last week.

This randomized, double-blind pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) study compared long-acting injectable cabotegravir (CAB), given every 2 months, with a control arm of daily TDF/FTC (brand name Truvada). The population was men who have sex with men and transgender women at high risk for HIV. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funded the study with the drug manufacturers (ViiV and Gilead, respectively) providing the study drugs.

In reviewing the results of the ongoing trial, a data safety and monitoring board (DSMB) found the data so compelling that they stopped the blinding and informed participants of their treatment assignment.

DSMB actions like this are generally big news — the same thing happened recently with the COVID-19 remdesivir study comparing it to placebo, showing a faster recovery time in the remdesivir arm. So let’s take a brief break from all-things-COVID and look in more detail at the HPTN 083 results.

The study enrolled 4570 participants with a mean age of 28 years; 12% were transgender women. Importantly, 50% of the U.S. enrollment identified as Black or African American, the group in this country at disproportionately high risk of HIV. Participants also came from Argentina, Brazil, Peru, Thailand, Vietnam, and South Africa.

During the study, 50 participants acquired HIV, for an overall incidence rate of 0.79%. Since the investigators predicted a background HIV incidence of 4.5%, these results show that both study arms were highly effective in preventing HIV.

But here’s where it gets really interesting — 38 of the infections came in the TDF/FTC arm (incidence, 1.21%), versus only 12 (incidence, 0.38%) in the CAB treatment group.

Let’s do the complicated math — there were about three times fewer HIV infections acquired by participants on CAB than on TDF/FTC.

Since there’s still no baseball, I’ll fill the gap by applying the appropriate metaphor — this most certainly is a home run for HIV prevention. And, if you prefer Greek epic poetry metaphors, it appears that injectable cabotegravir overcomes the Achilles heel of daily TDF/FTC, which is adherence.

Safety and tolerability of the two approaches were similar, though injection site reactions were more common in the CAB arm. Remember, though all received active drug, accompanying placebos were also administered — kudos to the study sites for pulling this off, that’s a lot of injections.

The press release stated that resistance testing is “in progress” — these data will be critical. If the failure of CAB leads to integrase resistance, this will be a substantial disadvantage to this otherwise very promising strategy.

An additional endpoint of some interest (also not yet reported) will be weight changes over time since TDF/FTC tends to suppress weight, while most integrase-based regimens in people with HIV lead to weight gain. No effect of cabotegravir on weight was observed in a small previous study, but there was no TDF/FTC control arm.

Importantly, HPTN 084, a parallel trial designed to evaluate CAB in comparison to daily oral TDF/FTC in women in sub-Saharan Africa, is ongoing. The results of both these studies will capture the populations at greatest risk of HIV globally, and fully round out our understanding of these two strategies of HIV prevention.

As noted here previously, the FDA delayed approval of long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine late last year, so as of today clinicians cannot prescribe cabotegravir for PrEP. But you can be sure these results will add urgency to completing the approval process, COVID-19 notwithstanding.

They also will amplify the importance of other long-acting PrEP studies in development, including the injectable capsid inhibitor GS-6207 and the nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor islatravir, which is also undergoing evaluation as an implant.

Before finishing, I offer this disclosure and a personal note. The protocol chair of HPTN 083 is Dr. Raphael (Raphy) Landovitz, a longtime friend and former colleague mentioned numerous times on this site. I first met him (many) years ago when he was in medical school, and noted him to be brilliant, opinionated, funny — and most emphatically (and refreshingly) not your typical stereotype of the successful academic.

When he left Boston for UCLA to work under the research mentorship of Dr. Judy Currier, the energy level of the country shifted noticeably westward. Our loss. Regardless, it has been enormously gratifying to watch him go from success to success, with HPTN 083 just the latest example.

And even though he and I don’t share hobbies — he’s passionate about Broadway musicals (hard pass for me) but can’t stand baseball — even I have to admit that this is very, very well done:

May 17th, 2020

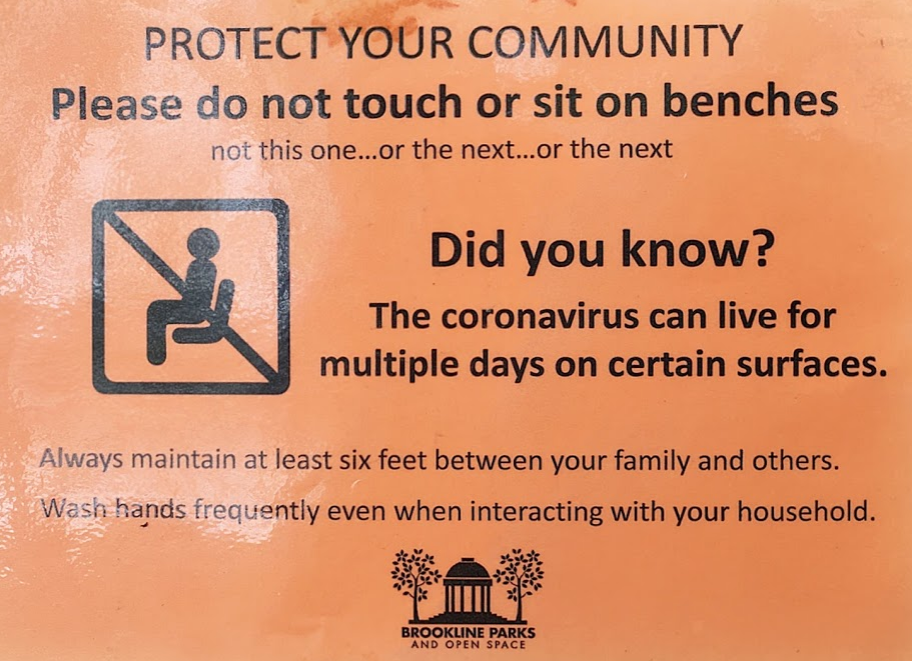

Does Strictly Limiting Outdoor Activities Help Prevent the Spread of COVID-19? A Call for Reason

I really miss playing tennis.

Tossing that out there to confess up front why the following might not be the world’s most objective perspective.

But take a look at this:

Jeepers, much of that advice strikes me as silly. Or, as put bluntly by one respondent here:

So, if I understand well, I can sleep with my wife but playing tennis with her just crosses the line, right? S**t, this is a tricky virus!

Ok, back to me and tennis. Some years ago, my wife gave me a nice tennis racquet for a certain milestone birthday.

She had just watch me play in a casual pick-up tournament for novice players at a local park, and noticed I couldn’t shut up about how fun it was for weeks.

It was easily one of the best birthday presents in the history of the planet. I’ve been playing tennis 2-3 times a week ever since. While walking, biking, or driving to the courts, I get this delightful giddy feeling of excitement each time.

Plus — and other devoted amateur athletes and hobbyists will certainly recognize this feeling — playing tennis is one of the few activities during which my mind goes blank on work issues. Patient care worries, manuscript deadlines, demands for learning objectives, human resources struggles, required online learning modules, email overload — all gone.

Boy, I miss that.

So I acknowledge some bias here on the question of whether strictly limiting outdoor activities actually limits the spread of COVID-19.

And — must be said — missing tennis is trivial compared to the hardships, health issues, and losses wreaked by this awful virus.

But follow me on the tennis thing anyway, because I do think that some of our most important public health messages get diluted by nonsensical and absolutist guidelines not rooted in science.

Where do we see most of the spread of COVID-19?

Households, especially those that can’t isolate symptomatic individuals due to lack of space. Crowded settings with poor ventilation. Nursing homes. Shelters. Ships. Call centers. Restaurants and bars. Parties. Family gatherings. Public transportation. Meat packing plants.

What do all of these settings have in common? They’re indoors. Or they’re crowded. Or even worse — both.

That’s because the likelihood of getting infected directly correlates with the amount of virus in the air we’re breathing, and the time we spend breathing it. Read this magnificent and widely circulated post by Dr. Erin Bromage, if you want more details.

Or this wonderful summary of carefully done transmission studies by Dr. Muge Cevik:

A lot of discussion recently about transmission dynamics, most of which are extrapolated from viral loads & estimates. What does contact tracing/community testing data tell us about actual probability of #COVID19 transmission(infection rate), high risk environments/age?

[thread]— Muge Cevik (@mugecevik) May 4, 2020

Outbreaks linked to outdoor activities invariably involve crowds — this Italian soccer match, for example.

How about the infamous Spring Break 2020 revelers, basking outdoors in that glorious sunshine while the rest of the country watched, horrified?

It’s possible that they contracted COVID-19 on the beaches, but much more likely these transmissions occurred during the evening hours while packed together like sardines — not just in their shared hotel rooms, but also while attending museums, poetry readings, and chamber music performances.

(Oops, I mean bars, bars, and more bars.)

Again, the problem with too-strict or illogical public health advice is that they make us distrust all the messages. As noted by population scientist Dr. Julia Marcus in this excellent and thoughtful piece:

The choice between staying home indefinitely and returning to business as usual now is a false one. Risk is not binary. And an all-or-nothing approach to disease prevention can have unintended consequences.

Some take-home messages? Yes, avoid crowds. And indoor spaces with poor ventilation. Keep your distance from others when you can — and when you can’t, limit the time spent in close proximity. And wash your hands a lot.

But do go outside and get some fresh air. Don’t yell at the jogger across the street without a mask, or the person having a picnic in the park with their family — they are not going to infect you.

And let’s be reasonable when it comes to public health messages, focusing on what really counts.

Tennis anyone?

May 10th, 2020

Thank You to Inpatient Nurses — The People Doing the Most Direct COVID-19 Patient Care

Anyone who does inpatient medicine or surgery knows well the major imbalance in time spent on direct patient care between doctors and nurses.

Nurses spend way more time actually with patients than we do — I’m referring to time in the rooms caring for patients.

While we round and review charts, document lab test results, bring up radiographic images, write orders, and debate the merits of the latest hydroxychloroquine or remdesivir study, they do direct assessments and respond most immediately to patient needs.

It’s been this way for years. The late Dr. Arnold Relman, former editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, sustained a major injury several years ago that required a prolonged hospitalization. Writing about the experience, he cited how doctors (vs. nurses) practice medicine today:

What I hadn’t appreciated was the extent to which, when there is no emergency, new technologies and electronic record-keeping affect how doctors do their work. Attention to the masses of data generated by laboratory and imaging studies has shifted their focus away from the patient. Doctors now spend more time with their computers than at the bedside. Reading the physicians’ notes in the MGH and Spaulding records, I found only a few brief descriptions of how I felt or looked. Conversations with my physicians were infrequent, brief, and hardly ever reported. What personal care hospitalized patients now get is mostly from nurses.

Emphasis mine.

COVID-19 only brings this stark disparity into sharper focus. A diagnosis of COVID-19 means necessary isolation — single room, no visitors. Clinicians must put on (“don”) personal protective equipment (PPE) to see patients, then take off (“doff”) the PPE without contaminating oneself — a strategy best done with an attentive monitor. It’s not easy to get it right.

Since PPE supply chains have been strained right from the start, we must limit the number of clinicians with direct patient care. Bring on the telephone or iPad consults — that was never a thing before. Way fewer doctors in the room, both during rounds and the rest of the hospital day. But all patients still have the same amount of nursing care.

We ID specialists say this again and again about the risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the cause of COVID-19. The riskiest activities involve spending prolonged time in close proximity to someone with the disease — especially someone who’s acutely ill and coughing.

And in the hospital, the health professionals doing most of this high-risk activity are the inpatient nurses.

I’ve thanked them before for this. But May 6-12 is National Nurses Week — an excellent reminder to be grateful again for what they are doing in this very challenging time.

May 6th, 2020

Early Memories of Burton “Bud” Rose, Founder of UpToDate — and Medical Education Visionary

Let’s rewind the clock a bit — OK, a lot. Ancient history.

Let’s rewind the clock a bit — OK, a lot. Ancient history.

It’s winter, 1986. An interview day for medical residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. A bunch of us nervous medical students sit in a conference room, wearing our interview suits, while Dr. Marshall Wolf tells us what to expect that day.

Amazingly, Marshall knows all our names already — which he proves by saying them out loud while handing us each folders.

The folders have our schedule for the day, including our interviews with faculty. One of my interviews is with Dr. Burton “Bud” Rose.

No exaggeration — he was already legendary among medical students. We all had his book, “Clinical Physiology of Acid-Base and Electrolyte Disorders,” which described this complex topic with astonishing clarity.

One of my medical school classmates, a brilliant guy but sometimes a bit of a bull in a china shop, described using this book during his medicine rotation:

His book gave me a rich and logical foundation in the field, along with a silly level of cockiness. The chief resident during my medicine clerkship asked why people with DKA develop hyperkalemia. I responded, confidently, “insulin deficiency and hyperosmolar solvent drag.” She said, “No it is cation exchange.” I replied, “You are wrong.” It went back and forth for awhile, and then I brought her the book next day. I was right, but it did not help my evaluation.

Not surprisingly, I’m awestruck to have an interview with Bud Rose. Even more nervous than before, if that’s possible.

But meeting Bud was great — he couldn’t have been more welcoming. And it was memorable, too — memorable for the precise sentences that made up his conversation (no surprise), and for one particular exchange indelibly imprinted in my memory:

Bud: What area of medicine interests you the most?

Me: Infectious diseases.

Bud: That’s my least favorite. Too much memorization. I prefer areas of medicine where you arrive at diagnoses by understanding basic physiology. (Smiling.) Like nephrology, for example.

Me: Can I change my answer?

Bud (laughing, fortunately): Too late. So convince me — why should someone like ID?

Me: Maybe because I was an English major in college — I like stories. And ID cases often have great stories — like the patient I saw who developed a knee infection from Pasturella multocida because his German shepherd licked between his toes every night. People often think of cats with pasturella, but dogs have it too.

Bud: That is a good story — it’s disgusting, but it’s a good story. But you had to memorize that dogs have pasturella, didn’t you? See, I’m right about ID. Too much memorization.

The conversation then went to his college major, which was History — he liked stories too — and how he ended up in medical school, why he loved teaching, how Boston differs from New York, why I should start playing tennis, and how Brigham medical residents supported each other.

It was a wonderful, far-ranging, and bidirectional conversation. Not intimidating at all.

Not once did he ask me about my less-than-stellar preclinical medical school transcript — relief — and to this day I’m grateful to have matched at the Brigham, no doubt due in some small part to my interview with the legendary Bud Rose.

During residency, he regularly stopped by our intensive care unit to review cases of renal failure and electrolyte abnormalities with us. He’d ask only for the numbers — the electrolytes, renal function, and glucose on a given patient — along with a list of the patient’s medications, and the primary reason for admission to the ICU. That’s it.

From these bare-bones presentations, he’d narrow down the possibilities for each of these cases to the two or three most likely diagnoses — sometimes the only diagnosis. It was a clinical reasoning tour-de-force, the likes of which to this day amazes me.

Let’s now fast forward from 1986 to, roughly, 1993. Yes, still ancient history — still long before the days of high-speed internet.

I’d been gone for a few years doing my ID fellowship, but now I’m back at the Brigham for an ID faculty position. Soon after returning, I get a call from Bud Rose — he wants me to come meet with him to discuss a project he’s working on.

He’s still in the same tucked-away office we had our interview in in 1986, but there’s something new in the room — a small computer on its own little table, barely bigger than the computer itself. I believe it was a Macintosh SE, with a tiny screen and two floppy disk drives.

Here’s our dialogue this time:

Bud: Imagine you’re seeing a patient, and she has hyponatremia. What are the first questions that come to mind?

Me: Hey, I’m an ID doctor — not a nephrologist, remember?

Bud (smiling): I haven’t forgotten that! But this works for anyone who does patient care. What comes to mind?

Me: Hyponatremia — what’s causing it? How serious is it? How do I treat it?

Bud: Exactly! Now if you were planning to manage this patient, you’d want the answers to your questions — normally you’d go to a medical textbook, and find the index, then the chapter on hyponatremia, and then scan for causes and prognosis and management. But what if you could leap right to the answers? And those answers could be updated rapidly with the latest research? Let me show you something.

He heads over to the computer, and launches a program called Hypercard — and writes in the search box, “causes of hyponatremia.” Instantly a paragraph appears on the topic. On the computer screen, I recognize Bud’s clear and well-organized writing, adapted from his textbook.

Bud (continuing): Now look at this — here’s some highlighted text. He moves his mouse over the word “hyperkalemia.” If you click on this word, it takes you to the card on that topic. I call them cards because they represent cards on a particular question, or problem, from my card file.

He points to a meticulously organized card file on which he’s summarized a staggering array of nephrology papers.

Me: Wow, that’s amazing!

Bud: Now I’ve just done this for nephrology. I would like to expand to all of medicine. Are you interested?

Me: Even ID? I thought you hated ID.

Bud: Not if you include the stories.

Of course I’m interested — how cool is that little machine! What he’s showing me in this meeting, of course, is a very early version of UpToDate — the preeminent “point of care” medical reference that has over time all but obliterated traditional medical textbooks.

Bud’s key insight is that what we clinicians want, first and foremost, is authoritative advice on how to manage our patients — and that advice stems from common clinical questions. The background information on pathophysiology, the basic research, the details of clinical trials, the epidemiology should only serve as foundations to this primary goal, answering these questions.

And it must be updated in real-time — no delays for publication of new editions. It isn’t called “UpToDate” for nothing. It anticipated the fast pace of biomedical research long before any other medical resource.

That the original program was distributed on floppy discs makes its success all the more remarkable. He couldn’t have anticipated the ubiquity of high-speed internet, or smart phones, or electronic medical records, but each of these has further solidified UpToDate’s leadership in this medical education space.

Google for medicine, but smarter and based on evidence. What a great analogy.

Bud told me many years ago his two favorite things in the world were taking walks with his wife and kids on a beautiful day, and playing tennis. After that, it was hearing from a clinician that UpToDate had helped improve patient care.

I don’t know how many family walks he took and tennis games he played — but no doubt thousands and thousands have benefited from that project he started on his small computer.

Bud Rose died April 24 2020 of Alzheimer’s disease and COVID-19.

April 27th, 2020

Leaked Remdesivir Study Information, Tocilizumab and Sarilumab Trials, and the Hazards of Early COVID-19 Research Findings

In the podcast I did with Helen Branswell — Infectious Diseases and global health reporter for STAT — she mentioned that the flow of scientific information for the COVID-19 pandemic made the commonly cited “drinking from a fire hose” analogy somehow inadequate.

Since she’s from Canada, I offered Niagara Falls as an alternative, to which she cleverly responded.

Yeah. It’s like standing out at the falls, trying to fill a glass of water. It’s overwhelming and it’s impossible to keep up.

She then mentioned the ascendancy of the preprint servers, which of course is part of this deluge. Never in the history of medical research has so much non–peer-reviewed data made its way to the public’s insatiably hungry (or should I say thirsty, to continue the analogy) view.

And it’s not just preprints. Let’s start with remdesivir, the repurposed antiviral making its way quickly through clinical trials — though apparently not quickly enough.

Here’s what we know as of today, April 27, 2020:

- There is one (count ’em) peer-reviewed published paper on use of remdesivir in COVID-19. It appeared right here in the august pages of the parent journal of this site, the venerable New England Journal of Medicine. It’s an uncontrolled

expanded accesscompassionate use study showing that it might work, and likely isn’t too harmful. That’s all we can say from this controversial publication — controversial because under normal circumstances, the New England Journal of Medicine does not publish studies like this. But they would argue (and I agree), these are far from normal circumstances. - Optimistic comments from a site investigator conducting a remdesivir study became public. During what sounds like a faculty meeting or medical grand rounds, the researcher said people in the study responded promptly to remdesivir treatment. Under ordinary times, this information would not have left the walls of the hospital, or even been mentioned at all — but these are not ordinary times! We conduct all meetings online, making them easy to record (and to leak, um, share). In the annals of “How is current life so bizarrely different from pre-COVID-19 life?,” let’s remember this one.

- Discouraging results of a partially completed study appeared on the World Health Organization’s site. More accurately — briefly appeared; it has now been taken down, but can still be read because someone took a screen shot, and shared it. The target sample size for this randomized trial was intended to be 453, but only 237 enrolled — whether the study was stopped due to a futility analysis or because the incidence of COVID-19 in China fell is not clear (the company statement implies the latter). Regardless, based on this now infamous screen shot, the drug did not significantly improve clinical outcomes. And yes, we’re now gleaning information from a blurry screen shot. Gosh, how we’ve changed.

Published, peer-reviewed data on remdesivir is expected soon — looking forward to that.

Speaking of looking for data, how about this one about tocilizumab, the humanized monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-6 receptor:

#Covid19 | #Tocilizumab improves significantly clinical outcomes of patients with moderate or severe COVID-19 pneumonia. First results of the #CORIMUNO-TOCI open-label randomized controlled trial https://t.co/L403gJ7rfF pic.twitter.com/TLiL8PAmCU

— AP-HP (@APHP) April 27, 2020

That’s all we get — just the title slide of what looks to be a PowerPoint presentation. Someone else offered additional data, perhaps an investigator?

Good news. 129 moderate or severe patients w/ #COVID19. 65 in #tocilizumab arm, 64 in control arm. Endpoint: death or need for mechanical ventilation by D14. Tocilizumab significantly superior to control arm. Publication will follow soon.

Tantalizing! But is there more? Peer-reviewed journal next, or preprint server?

If that’s not enough for a Monday a.m., we also have this announcement about sarilumab, another monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-6 receptor. Here’s an excerpt from what is a quite complex (and confusing, at least to me) summary:

Analysis of clinical outcomes in the Phase 2 trial was exploratory and pre-specified to focus on the “severe” and “critical” groups. In the preliminary Phase 2 analysis, Kevzara [sarilumab] had no notable benefit on clinical outcomes when combining the “severe” and “critical” groups, versus placebo. However, there were negative trends for most outcomes in the “severe” group, while there were positive trends for all outcomes in the “critical” group (see table below).

Got that? Negative and positive trends.

So why is this happening? To overstate the obvious, we are all so desperate for good news on therapy for this terrible infection that we hang on every released word. And the rapidity of communication these days allows such preliminary messages to appear instantly!

But there’s definitely something missing, too. Actually, a lot missing.

Let’s take the tocilizumab study: No details on inclusion or exclusion criteria. No sample size calculation or statistical methods section. Nothing on screen failures. Nothing on dosing, duration of follow-up, concomitant therapies. No “Table 1” of baseline characteristics. No information on clinical outcomes. No safety data.

And of course, no peer review. Oh well.

With sarilumab, we have more information, but it’s so convoluted I don’t think anyone can make an assessment of whether this treatment is helpful, or harmful, or in what populations.

And for remdesivir? One grows tired of getting “critical” medical information from images that probably should have been communicated by Snapchat, if that.

Though come to think of it — what a great analogy. Because nothing ever dies on the internet.

Hey, listen to Helen Branswell tell her story!

April 19th, 2020

Gratitude Before, During, and After Rounding on COVID-19 Service

It snowed in Boston yesterday morning — heavy, wet flakes covered the daffodils and tulips that just started coming up — but this brief return to winter didn’t make my red, itchy eyes from spring pollen feel any better.

The flowers didn’t look too happy either. Oh well.

But just as the annual misery of a typical Boston April started to bug me, the work at the hospital provided plenty of distraction — in a good way. Because even in the midst of this terrible pandemic, there are many reasons for gratitude, some big and some small.

Today’s theme — appreciation for people doing an astounding job under truly difficult circumstances. This is hardly a comprehensive list, but just the things that came to my attention during rounds yesterday.

1. Enter the hospital. In US hospitals now, patients and staff must enter through different doors; at the staff entrance we show our ID badges, then our electronic COVID PASS attesting we’re healthy enough to work, and then we pick up our daily surgical mask. Sounds like a huge pain, right? In fact, the people working at these entrances exemplify kindness and efficiency. Not only that — masks with elastic loops (rather than loose ties) showed up this week back in stock, making life so much easier. Thank you.

2. Pick up your scrubs. Most people caring for patients with COVID-19 wear scrubs, and of course this increased demand strains the scrub distribution system. But so far it’s working out mostly ok, with machines dispensing clean sets in your designated size without much difficulty. I haven’t worn scrubs since residency — a long time ago, yikes — and my amazement at this automated system brought to mind George Bush, Sr.’s clueless response to supermarket price scanners in 1992. In my defense, my last time wearing scrubs was even before this date! Regardless, to the people washing the scrubs and stocking these machines — thank you.

3. Put on your PPE. Even after you’ve done it a bunch of times, it’s not easy putting on this personal protective gear — so many places you can go wrong. Fortunately, observers stationed outside of each room guide us through every step. Marie, Diego, Tommy, Danielle, Lucy (to list 5 of many) — all have been extraordinarily helpful, patient, and responsive, even though this isn’t even close to what they usually do in their actual jobs. They’ve been reassigned from the OR, the emergency room, the surgical floors, or the radiology suites to provide this important service. Thank you.

4. Work in a clean, comfortable place. Hospitals need to be clean, but that’s no easy task. Ever see what the resident work or call rooms look like after lunch? Eek. As we’re cogitating over CRPs and D-dimers and ferritins, the people responsible for keeping our patient floors clean work hard and mostly silently, invariably in the background but very much appreciated. Thank you.

5. Get the update from the nurses. In our “SPU’s” — that’s “Special Pathogen Units”, name not chosen by me — the nurses on the floors have been simply amazing, providing remarkable care under very challenging circumstances. A key thing every ID doctor learns early in his or her training is that if you want the complete picture of how someone is doing, ask the patient’s nurse. They’re the ones in the rooms the most, a reality more true now than ever given the need to preserve PPE and other barriers to patient visits. Thank you.

6. Work with dedicated medical trainees. Medical interns and residents. Surgical versions of the same. ID fellows, dermatology trainees, and budding oncologists. Future cardiologists and invasive gastroenterologists and thoracic surgeons-to-be. One thing you can confidently say about all of them — NONE EXPECTED TO BE DOING THIS RIGHT NOW. (All caps, italicized, and bolded for emphasis.) None signed up for this — not even the ID fellows! All of their planned training has been completely sidelined by a few pangolins (maybe) and SARS-CoV-2. Regardless, the trainees’ sustained calm and pleasant demeanor, their competence, and the compassion with which they approach patient care in the COVID-19 era cannot be overstated. Plus, they want to learn about this scary new disease — no running away, they have genuine interest. Just amazed and impressed. Thank you.

7. Get breakfast, lunch or dinner. By my quick calculations, I estimate that I have eaten 8,423 meals either in our hospital’s cafeteria or the coffee place in the lobby. COVID-19 changed how we get and consume food, but both the cafeteria and coffee place still open daily for business — and all the people working there smile (you can tell by looking at their eyes above their masks), and the food is still fine. And good value! Thank you.

No, things aren’t perfect. The lines for scrubs right before shift changes stretch out into the hallway (6-foot separation!), our elevators in our oldest patient tower still could … be … faster …, there’s no salad bar, and I’ve already complained about the masks with the tricky ties (doing it behind your head is so tough for fumble-fingered non-surgeons).

But boy, things could be worse.

Hey, it reached 60 degrees today! Thanks for that, too.

Mabel and Olive, go at it.