An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

November 29th, 2020

Great Questions from Our Course, Infectious Diseases in Primary Care — Plus Bonus Podcast

Going to take a partial break from all things COVID-19 today and recap some of the terrific questions we received in our course, Infectious Diseases in Primary Care.

Not surprisingly, there were plenty of COVID-19 questions but also the usual mix of practical queries from everyday practice.

Front-line clinicians doing office-based practice attend this course, and every year, they remind us of the common problems and quandaries they face in their day-to-day work. It’s a great mix of general internists, family practitioners, nurse practitioners, and PAs.

This year, of course, we held it virtually due to the pandemic, bringing with it predictable trade-offs.

On the plus side, more people could attend, the lectures are available to watch on-demand (at least for a while), and also the barrier to asking questions was lower — just type in a question and send!

On the other hand, we missed the personal interactions with participants and couldn’t get immediate feedback on whether what we were teaching was useful — watching people during teaching gives you a real sense of whether they’re with you on the topic or perplexed. Finally, humor during teaching is all but impossible to gauge — did the jokes land or fall flat?

But we got some amazing questions and didn’t have time to answer them all, so here’s a baker’s dozen and some quick answers.

Question #1: Would you give the recombinant zoster vaccine to someone who is 40 and at high risk because they are immunocompromised?

Answer: The quick answer is that the ACIP doesn’t yet recommend it in this population, but it has been studied in a variety of immunocompromised hosts (autologous stem cell transplants, rheumatoid arthritis), and it is safe and effective. So in general, the answer is don’t give it to people younger than 50, or to the severely immunosuppressed, at least for now; future guidelines may change, so stay tuned. (And of course, insurance may not cover it in this population.)

Question #2: Can you address the sensitivity/specificity of the rapid antigen tests for COVID-19 and the problem of low vs high pretest probability?

Answer: Since the antigen tests do not have an amplification step (unlike the PCR), they are less sensitive for detection of the virus. Despite this drawback, their rapid turnaround time makes them quite useful in certain settings. In a case where the pre-test probability is low — such as in an asymptomatic person with few or no high-risk exposures — a negative test further reduces the post-test probability that the person has asymptomatic COVID-19. Antigen tests are also quite likely to be positive in those who are most infectious.

By contrast, in a person who has compatible symptoms, a negative antigen test would not be sufficient to rule out the disease, especially in the hospital. Stick with PCR for those cases.

Question #3: What do I do when a job requires varicella titers, and they come back negative? The patients did receive their primary varicella vaccine series.

Answer: The varicella titers we do in clinical practice do not reliably assess for vaccine-induced immunity. Hence, we do not recommend them for this purpose, and the patient should provide proof of having had the primary series as sufficient evidence.

Question #4: Do we need to give a hepatitis B booster if it’s been a long time since the primary vaccine series? Someone recently told me he received it more than 30 years ago.

Answer: In general, boosters are not recommended after the hepatitis B vaccine series — especially if follow-up titers showed that at some point after the vaccine, the patient responded. (Checking is recommended for healthcare workers.) Even if the titer is now negative, exposure to hepatitis B will induce an anamnestic (always hard to pronounce!) response, so people will be protected.

One common exception to this rule is for people on hemodialysis. A repeat vaccine would be indicated if their titers all below 10 mIU/mL. Some people also recommend this strategy for other immunocompromised hosts, but this is not yet fully endorsed in guidelines. Here’s a great list of hepatitis B FAQs from the CDC.

Question #5: For fecal transplants, why do we not accept stool from obese donors?

Answer: There is evidence that the microbiome of normal versus overweight people differs and also that antibiotic administration (at least in childhood) leads to weight gain — remember, this is why livestock and poultry receive antibiotics, to fatten them up! Plus there’s at least one case report of emergent obesity after fecal transplant from an overweight donor. Unfortunately, we don’t have evidence yet of the converse — that normal-weight donors lead to weight loss in those who are overweight.

Question #6: Any evidence that vitamin D supplementation prevents or treats COVID-19?

Answer: Studies have shown that there is an association between low vitamin D levels and a higher risk of testing positive for COVID-19 and that people hospitalized with the disease have lower levels than population-based controls. One small, randomized trial also suggested a possible benefit of giving vitamin D.

While these data suggest that supplementation will help, remember that low vitamin D levels correlate with poor health in general and that the road is littered with failed studies of vitamin D treatment for a wide range of conditions, including critically ill people with respiratory failure. Pending the results of a fully powered study of vitamin D in COVID-19, we don’t currently recommend it.

Question #7: For our stable HIV patients, please specify which statins can be given safely with ART. (Note: I didn’t write “HAART”.)

Answer: It all depends whether the ART (and thank you for not saying “H—T”!) contains the pharmacokinetic boosters ritonavir or cobicistat, which can dangerously increase levels of certain statins, especially simvastatin. If not, especially if they’re on a dolutegravir- or bictegravir-containing regimen (as so many people with HIV are these days), then you can use any statin.

But if ritonavir or cobicistat is in the mix, go with low-dose atorvastatin (10-20 mg daily), as levels will increase 2-4 fold. Another alternative is pitavastatin — no interaction potential — though insurance sometimes doesn’t cover this one. Finally, efavirenz lowers atorvastatin levels somewhat, so starting with a slightly higher dose is reasonable. And if you’re not using the Liverpool HIV Drug Interactions site, start now!

Question #8: How should we dose trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for skin and soft tissue infections?

Answer: While a pivotal large clinical trial used two double-strength tablets twice daily, observational studies show no difference in outcomes between this and the standard 1 DS twice-daily approach. PharmD Bryan Hayes provides a nice summary of this controversy.

My practice is to recommend 2 DS twice daily for large and young people, and 1 DS twice daily for smaller and elderly patients — I’ll let you decide if this seems like a reasonable approach. And for the non-pediatricians out there, remember that each double-strength tablet contains 160 mg trimethoprim and 800 mg sulfamethoxazole — amazing how few clinicians of adults know that!

Question #9: It is my understanding that a tick must be attached for over 24 hours for a patient to get Lyme disease. Is that correct? Does this influence your approach to preventive therapy?

Answer: You are correct about the need for tick attachment for at least 24 hours before Lyme transmission, but the practical problem is that the ticks don’t provide us time-stamped receipts for how long they’ve been snacking on our blood. (So inconsiderate of them.)

So unless one has clear evidence about timing — went for a hike in the afternoon, tick found that evening — we tend to be quite liberal in our administration of preventive therapy, meaning that pretty much anyone who asks for it gets it. This goes against the guidelines, but it’s a much more real-world approach! Remember, too, that black-legged ticks are now ubiquitous in our region — one can pick them up doing pretty much any outdoor activity.

Question #10: If I treat someone for early Lyme, is there any reason to get a follow-up Lyme titer to confirm that my clinical diagnosis was correct?

Answer: Generally not — both because it won’t alter your approach to future therapy (people can get Lyme multiple times) and because there is some evidence that early antibiotic therapy blunts the antibody response to this infection. Some might argue that it’s good to have a baseline for future evaluations or to check based on curiosity alone, but neither reason in my opinion is sufficient to warrant doing the test. And yes, that’s two Lyme questions in a row — hey, this is New England!

Question #11: Corticosteroids used to be recommended for herpes zoster for prevention of the post-herpetic neuralgia. Can you comment on this?

Answer: While some older clinical trials suggested that steroids helped reduce pain in patients with acute herpes zoster, a Cochrane review of several randomized studies showed no aggregate benefit. A further limitation is that many of the studies excluded patients with even small contraindications to steroid treatment, such as having diabetes or being on immunosuppressive therapy. As a result, we ID docs don’t routinely recommend them — but the neurologists still sometimes do, and admittedly, a short course is unlikely to be harmful.

Question #12: What negative side effects of long term antibiotics do you educate patients about? (I have some on antibiotics for years from ‘Lyme specialists’.)

Answer: While the adverse effects of this strategy are well-documented (line infections, resistance, C. diff), it can sometimes be difficult to communicate this in a non-judgmental way. One sometimes useful strategy is to refer them either to the CDC site or, if they want something with a bit more narrative and without government associations, the Lyme Science site. The latter is a remarkable (and quite frightening) resource. Sorry, yet another Lyme question — there were so many!

Question #13: My patient had an illness consistent with COVID-19 in the spring but was never tested since there was such a shortage. Now he has prolonged post-illness fatigue and “brain fog” and wonders if he has “long COVID.” His antibody test is negative. Help!

Answer: This is a huge challenge on multiple fronts, as it’s possible he had COVID-19 in April but that his antibody titer has declined — it’s highly variable from person-to-person and also depends on what assay is being used. We unfortunately have no routine way to measure cellular immunity. Of course, it’s also possible he had a different viral respiratory tract infection.

Since I ended on this difficult topic of COVID-19 long-term symptoms, time to plug our latest podcast on Open Forum Infectious Diseases. Joining me is Dr. Vinay Prasad from UCSF, covering a wide range of COVID-19 issues, including treatments, research, long COVID, publications, and policies.

He has some remarkable (and controversial, no surprise) insights. You won’t regret it.

(Transcript here.)

November 24th, 2020

Some ID Things to Be Grateful for This Holiday Season — 2020 (!) Edition

“Grateful?” some might wonder. “He must be out of his mind.”

But even in the cursed year that began shortly after the first report of the disease now known as COVID-19 on (almost) New Year’s Eve, we can still find some things to praise, and to offer our gratitude. Or at the very least, acknowledge that without them, things would be so much worse.

Plus, it’s become an annual tradition on this site.

So here’s a list to get us started, just in time for Thanksgiving.

The remarkably high efficacy of experimental COVID-19 vaccines. These vaccines could have been a complete bust. Or like the flu vaccine, 40-50% effective in a good year, less than 20% in a bad one, usually worse than a coin-flip. Or accompanied by terrible side effects.

Instead, not only are the first two vaccines roughly 95% effective, but they prevent severe disease, including (by report) in the most vulnerable populations. No major side effects reported (yet). And they were developed with record-breaking speed, using a novel messenger RNA technology that is quite brilliant — even if it is totally obvious, ha ha.

love this

Nation Can’t Believe They Spent So Long Overlooking Obvious Solution Of mRNA Instructions For Spike Protein Encapsulated In Lipid Nanoparticle https://t.co/hi8kYHxhgb via @theonion h/t @_j_sax

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) November 20, 2020

Now reports show a third vaccine is effective even without this (so obvious) mRNA approach.

To the scientists who started working on these vaccines, to the labs and factories that put them together, to the companies that bet big on them, to the NIH for supporting the research, to the clinical research teams who enrolled tens of thousands of people working tirelessly for months, to the participants who volunteered — we owe our most heartfelt thank you.

The endurable scientific acumen and utter professionalism of Dr. Anthony Fauci. One of my patients, a no-nonsense guy in his late 40s who manages a car dealership, brought him up the other day out of the blue. “I love the guy,” he said. “He gives the medical information, doesn’t sugarcoat it, and doesn’t care about the political stuff.”

Exactly. We’ve all seen Tony (which is what everyone calls him) rise to the occasion during previous infectious threats, speaking about the science without reverting to hyperbole or pandering to his audience, but what he’s done with COVID-19 continues to amaze — he’s living what he describes as his “worst nightmare,” yet hardly misses a beat.

Even after retirement, people often referred to Joe DiMaggio as “The Greatest Living Ballplayer.” So do we have in Tony Fauci our Greatest Living ID Doctor? I think we do — though while he’s in great shape, he should work on improving his pitching.

The people who keep the hospitals running, but never get enough credit. I’m referring to the hard-working folks in food services, housekeeping, transport, engineering, security, phlebotomy, IT, laundry, admissions, and a whole slew of other jobs that make hospitals function — they are all coming to work each day, just like us clinicians, but (I’ll say it again):

They never get enough credit.

So here’s some credit — thank you so much!

The arrival of telemedicine (finally). In the Before Times, several barriers stopped telemedicine’s full adoption. But there was one big fat elephant in the room blocking the doorway, which was that most doctors would only get paid for face-to-face visits. It didn’t seem to matter that telemedicine could make patient care better and more convenient by improving access and limiting wasteful travel time.

And there were technological hurdles, too. While everyone else used fancy video calls and web conferencing that would make George Jetson jealous — Zoom existed before COVID-19, you know — most of us clinicians had to put up with systems that were buggy at best and didn’t work at all at their worst. And just try and coach a technophobe on how to download a proprietary secure app onto their cell phone, create a username and password, and log on.

Since COVID-19? Presto-Chango, telemedicine has very much arrived — so much so that for certain specialties (psychiatry, endocrinology, some primary care), virtual visits now can outnumber in-person appointments. One of my friends does all her routine surgical post-op checks virtually, only bringing patients in if there are problems or if her patients request to come in (most don’t). And most payers get it, and pay for it, at least for now.

Plus, the technology is much better. Zoom has come to patient care, and I’m also a huge fan of Doximity dialer.

Regulatory and payment issues remain (in particular providing virtual care across state lines), but telemedicine is too good and too important to allow it to go away, even after the pandemic is over. It’s here to stay.

Our remarkable hospital microbiology laboratories. These magnificent places have always held wonder for us ID doctors, providing both fascinating information about our cases and, in turn, making us look smart. Thank you for that!

But what they’ve done since early 2020 is nothing short of extraordinary. As everyone knows, test shortages for SARS-CoV-2 consistently hamper our country’s COVID-19 response. Even with this pressure, the microbiology labs have nonetheless pulled together enormous resources to make testing continually available in hospitals, and they have employed multiple redundant platforms to ensure that the system doesn’t break down

Oh yeah — they continue to do all that other stuff (stains, cultures, sensitivities, PCRs, MALDI, antigens, antibodies) we need for patient care. Amazing.

The meticulous and hard-working infection control practitioners. For non-ID readers, it may surprise you to hear that within the field of Infectious Diseases there is a group dedicated specifically to the field of infection control. They are key players in keeping us safe while working in the hospital; their reach extends to outpatient activities as well.

Not surprisingly, they are by nature drawn from a certain type of detail-oriented person. Here’s what I wrote a few years ago when discussing the “raging” controversy over whether doctors should wear white coats:

People who specialize in Infection Control are some of the most measured, data-driven, and methodical individuals in all of medicine. You know the stereotype of the brash, volatile, and cowboy surgeon, the person that everyone tiptoes around? These Infection Control folks are the polar opposite.

They also have a drive to get things right. During the pandemic, when many of us are working harder than ever, the specialists in infection control (mostly doctors and nurses) have simply not rested for months. I’m enormously grateful for all that they do.

Long-acting cabotegravir for HIV prevention. Had to get one non-COVID thing in here, and this was the easy choice. Daily TDF/FTC and TAF/FTC work great for pre-exposure prophylaxis, yes — but only if you take it. Plus, the data in women didn’t quite reach the high efficacy in men.

Which is why the results of HPTN 083 (men who have sex with men, transgender women) and HPTN 084 (at-risk women) are so exciting. In these studies, while TDF/FTC was effective, an injection of cabotegravir every 8 weeks was even better — so much so that both studies could be stopped early. Hooray! We are all looking forward to seeing more when these studies are published.

Honorable mention. There are bunch more things I could have mentioned, but this post has already gone on too long. Sorry!

So just briefly, here are a few, rapid-fire style — the ancillary bonus of how social distancing decreases influenza and other respiratory viral illnesses; the highly qualified people on the president-elect’s COVID-19 task force; the way the pandemic reinforced ID’s commitment to support health equity; the insightful voices of Zeynep Tufekci, Julia Marcus, Ed Yong, and certain other non-MDs in making us all think a bit deeper about what this all means; that more people can attend conferences since they went virtual; that most of us haven’t had to suffer an interminable airport delay since forever; that my favorite sports (tennis and baseball) are naturally socially distanced; that people rediscovered the great outdoors as the safest place to socialize; the Olive and Mabel competitions (“a bit of showboating, needs to be careful”); the poems America and Good Bones; and that this guy does the best The Crown impressions you’ll ever see.

https://youtu.be/-LQTBOBfA18

You get the idea. So what are you grateful for in late 2020? Don’t be shy.

November 18th, 2020

Just Another Urgent Plea from Your Friendly ID Doctor for Risk Mitigation as the Holiday Season Approaches

There’s lots in the press about how to have safe holiday gatherings in 2020 as cases of COVID-19 increase pretty much everywhere in this country.

How about this simple strategy?

Celebrate only with the people you live with already.

Bingo. That way Thanksgiving will be no riskier than your daily meals together.

End of advice column, right?

The problem is that this is analogous to advising abstinence for birth control or for prevention of sexually transmitted infections. It’s scientifically accurate, but the chances of 100% adherence by 100% of the population are zero.

So if we assume that this advice will not be followed by all — and that’s quite a fair assumption — how can we mitigate the risk?

Let’s make a list:

1. Keep the gathering small. Got a kid in college coming home for vacation? Sorry, the roommate can’t join the fun this year. No neighbors either.

2. Eat outside. Not so easy in New England, but as my hardy friend said, there’s no such thing as bad weather, just bad dressers. Plus the long-term forecast predicts warmth! Optimism!

3. Stay distanced if indoors. No, there’s nothing magic about 6 feet apart. But 6 feet is safer than 3 feet, and 9 feet is better than 6. You get the idea.

4. Wear masks while indoors and not eating. You do it now in public. You do it if someone comes to the house for a delivery or an appliance repair. Do it at home too if you have a visitor, even if it’s a family member.

5. Ventilation, ventilation, ventilation. This is for those who can’t eat outside. Open the windows. All of them. Here’s some more detailed advice from an expert, which most of us ID doctors emphatically are not:

I’ve seen a lot of questions about the importance of ventilation and the spread of SARS-CoV2. I have expertise in the science of indoor air quality & want to share some simple steps you can take to make your home & family safer during the pandemic. 1/

— Paula Olsiewski (@polsiewski) November 17, 2020

6. Keep the eating and drinking together time short. Risk of COVID-19 is a complex summation of distance, time, and activities during exposure to a person who’s infectious. And there’s hardly anything riskier than eating and talking together indoors — especially if the conversation becomes raucous, with people shouting.

7. In the week before the gathering, strictly limit social activities. Restaurants around the country are still open. Many places of worship are too. Time to start getting take-out food (tip well!), or joining your congregation electronically.

8. Give elders and otherwise vulnerable people an easy way to opt out. Even better, encourage them to join by zoom, facetime, google meets, or whatever platform is easiest for them. Study after study after study shows that this isn’t the same disease in everyone. Look at this figure — is there another infection that so shockingly discriminates by age?

The effect of age on the #COVID19 infection fatality rate. Just published @nature, data from 45 countries, 22 seroprevalence studies https://t.co/TWSogoHMMh

by @meganodris @hsalje @SCauchemez @fdlwang @datcummings @andrewazman and colleagues pic.twitter.com/pXtvZky4xA— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) November 2, 2020

9. Remember, it’s likely going to be weird like this for just one year. Got to love those vaccine study results — roughly 95% efficacy for two different vaccines! In a year’s time, let’s make getting your COVID-19 vaccine the ticket to gathering safely.

10. Get tested. Even better, get tested more than once, especially in the days leading up to the event.

Some might be surprised to read the advice about testing, which has gotten a bad name because it’s not fail-proof.

Am concerned that headlines like this (which are widespread) will discourage people from testing before seeing family. No, the tests aren't perfect, but they are *far* better than nothing. Get tested! Even if symptom-free! https://t.co/uBJ2O6rxeN

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) November 16, 2020

But this is not an all or nothing thing. Some testing is better than no testing. Remember, a negative test if done on a person without symptoms — even using less-sensitive antigen tests — lowers the likelihood that this person has contagious COVID-19.

It doesn’t replace the other strategies. But it does augment them.

Thank you for your time.

November 15th, 2020

Bamlanivimab for COVID-19 — Hard to Pronounce, Even Harder to Give

The latest COVID-19 treatment made available under Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) is bamlanivimab, a monoclonal antibody developed by Eli Lilly. For now, its use will be limited to outpatients who are at high risk for severe disease and/or hospitalization.

This EUA is based on the results of the phase 2 BLAZE-1 study, in which the treatment reduced the need for hospitalization among outpatients — especially those deemed at high risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes. For this group, 3% of bamlanivimab versus 10% of placebo recipients required admission.

And yes, you read that right — bamlanivimab.

The comedians sure had a field day with this tongue-twister, and boy it’s devilishly hard to say.

But let me focus instead on the difficulty of actually giving this product to a stable, high-risk outpatient with COVID-19 — because remember, that’s the only way it’s going to help anyone.

I’ve been ruminating over the challenges of implementing this treatment for a while, ever since research began on this class of drugs. Pharmacist Tim Gauthier’s outstanding summary amplified my concerns when he wrote that the logistics of administration would be “considerable” — which could be the understatement of the year.

Why so difficult? Let me list the ways:

- Supply is limited. Even accounting for the high-risk criteria listed in the EUA, the potentially eligible recipients will greatly exceed the number of distributed doses. How bad is the mismatch? This excellent review by my ID colleagues Drs. Robert Goldstein and Rochelle Walensky estimates that based on current case counts, the supply could be exhausted in less than 2 weeks. How will we choose who gets it?

- It must be given within 10 days of symptom onset. Some experts think even 10 days is too long a wait for effective intervention — the sooner the better. While we don’t know the precise window of opportunity for benefit, remember that these monoclonal antibody treatments (from both Lilly and Regeneron) don’t appear to help people already in the hospital.

- It must be given intravenously. How many outpatient clinicians have the ability to give infusions in their clinics?

- People with early COVID-19 disease are at their most contagious. Most secondary transmissions happen between 1 day before and 5 days after the onset of symptoms, during which time respiratory viral load peaks. And this is precisely when we’ll want to bring patients in for treatment.

- Most infusion centers have a high proportion of patients who are immunocompromised. Rheumatology, GI, and neurology patients receiving intravenous immunosuppressive agents. Cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. How can we safely bring COVID-19 patients into these centers? Should we even try?

- Many infusion centers are not set up for urgent referrals. Their regular patients have regularly scheduled infusions. Even setting up an urgent dose of ceftriaxone can be challenging if the schedule is already full.

- Both the infusion and the post-treatment monitoring take a lot of time. This isn’t a simple matter of showing up, getting one quick shot, then leaving. The infusion takes 1 hour, and there is a 1-hour monitoring period afterward to ensure no severe allergic reactions ensue. Budgeting 3 hours seems about right.

- Emergency departments do not want a 3-hour treatment clogging up their patient flow — especially if they don’t get paid. Unlike most infusion centers, hospital emergency departments do have the required infection control capabilities. However, would they welcome stable COVID-19 patients sitting around getting a 3-hour treatment? If so, how many? Not only would this distract from other critical activities, but under current systems of reimbursement for ED visits, there is no guarantee that the hospital will be paid for this service.

- The formulation is tricky to prepare and not stable for very long. Tim’s a pharmacist, so let me just quote him directly: “Preparation of the IV admixture is not simple and is stable for just 7 hours at room temperature or 24 hours under refrigeration (including infusion time).” Ugh.

- Serious side effects may occur. Although not in the published paper, the package insert cites at least one case of anaphylaxis and another serious infusion reaction among banlanivimab-treated patients. As a result, we are advised that this treatment “may only be administered in settings in which health care providers have immediate access to medications to treat a severe infusion reaction, such as anaphylaxis.”

Practically, these gargantuan logistical hurdles may make the limited supply moot — all of us are trying to figure out how to deliver this promising treatment to prevent hospitalizations, and it’s not an easy nut to crack.

But already there’s a sense that these difficulties could exacerbate existing disparities in COVID-19 outcomes, with underserved populations missing out again on the benefits of this tricky treatment.

Let’s imagine a hospital or other healthcare delivery system sets up a program to administer banlanivimab to people diagnosed with COVID-19 as outpatients. Because of drug supply constraints and the duration of the infusion and monitoring time, they limit the number of treated patients to two per day (a morning and an afternoon session), which is to be administered in a specialized infusion site separate from immunocompromised patients.

Patients are referred by their primary clinicians, or they can call themselves. An intake nurse or other health professional speaks with them, reviews the relevant medical history, and ultimately determines whether they meet the “high-risk” criteria for treatment. If so, they schedule the patient for one of the two daily treatment slots.

Sounds simple, right?

Now let’s consider two imaginary (but quite plausible) patients newly diagnosed with COVID-19, both of whom would meet eligibility criteria for banlamivimab therapy.

The first is a 74-year-old semi-retired lawyer with hypertension and adult-onset diabetes. He could lose a few pounds, so tries to play tennis at his club in Wellesley as often as possible. He gets regular check-ups in the hospital system’s primary care network. Because of that network, he periodically receives health alerts through his hospital’s patient portal, including reminders to schedule his eye exams, blood tests, and immunizations.

The second imaginary patient is a 71-year-old woman from the Dominican Republic who moved to Boston five years ago to live with her daughter and grandchildren. Although she worked at a restaurant before she moved (gaining quite a few pounds with on-the-job snacking), she now finds the language barrier difficult here, so does not work. She mostly stays at home, sometimes socializing with other older people in her neighborhood who also speak Spanish. She receives some primary care at her local community health center; they have recommended that she start treatment for high blood pressure and diabetes, but the clinicians keep changing, and not all of them speak her language, so she never did.

Which patient is most likely to be referred for a banlanivimab infusion? Which one is more likely to call and advocate for themselves?

I suspect no one needs a medical degree to answer those questions.

November 10th, 2020

Promising COVID-19 Vaccine Results and Progress on HIV Prevention — All in One Great Day

Monday, November 9, in the bedeviled year 2020, was an astounding day for research on prevention of infectious diseases — really unprecedented.

First — we awoke to hear that the Pfizer-BioNTech experimental COVID-19 vaccine was “90% effective” in preventing the disease after the second (of two) doses.

This was a planned interim analysis, taking place after 94 cases had occurred in 44,000 volunteers, with 39,000 completing the full series. No major safety concerns yet reported.

We of course need to review the full data, but these results are far better than any of us expected. For other viral respiratory infections, we have flu vaccine at one extreme of efficacy (20-50%, depending on the season), and measles at the other (90% or higher, and lifelong). Who could have predicted that the first SARS-CoV-2 vaccine result would be closer to the latter?

My ID colleague Dr. Mark Siedner and I wrote a primer on how to interpret the data, when they come out. Check it out!

Second — we learned the results of a critical HIV prevention study, HPTN 084, which compared TDF/FTC given once daily to injectable cabotegravir given every 8 weeks in HIV-negative women in Africa. Over 3000 women were enrolled at sites located in Botswana, Eswatini, Kenya, Malawi, South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.

Thirty-four HIV infections occurred in the TDF/FTC arm vs only four in the cabotegravir arm, a nearly 9-fold difference. As with HPTN 083 done in men who have sex with men and transgender women, the TDF/FTC strategy was effective, but the cabotegravir strategy significantly more so — a difference big enough in 084 to prompt the safety monitoring board overseeing the study to recommend stopping the blinded phase of the trial.

In a background of disappointing PrEP studies conducted in this population (African women), these results are particularly impressive. And because the Pfizer vaccine study dominated the day’s news (understandably), you might have missed this — hence I’m highlighting it here.

Wow, what a day. Thanksgiving came early in 2020, didn’t it?

November 1st, 2020

A Series of Disappointing Results of Immune-Based Therapies for COVID-19

It’s been a tough couple of weeks for immune-based therapies for COVID-19.

It’s been a tough couple of weeks for immune-based therapies for COVID-19.

We know that immune modulation in this disease, especially in its most severe manifestations, can improve outcomes.

Favorable results from the RECOVERY study of dexamethasone have made it the standard of care for most hospitalized patients who require oxygen. And we also know that our own immune system plays a major role in clearing this nasty virus.

So can we succeed with more targeted approaches? Either inhibition of our overly exuberant immune response or “boosting” our own immune systems through monoclonal antibodies?

(Some might classify the latter as antivirals rather than immune-based therapies. How about considering them both?)

Let’s start with tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 (IL-6) inhibitor widely used off-label for treatment of COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic. Multiple observational and small prospective studies also strongly suggested clinical benefits.

Well, in a remarkable 48 hours late last month (October 21-23, to be exact), no fewer than four multicenter randomized clinical trials of tocilizumab appeared in print — three in peer-reviewed journals and one as a pre-print. All were done on hospitalized patients not receiving mechanical ventilation, and all compared tocilizumab with a “usual care” control.

- RCT-TCZ-COVID-19 (n=126): The primary endpoint was hypoxemia (protocol defined), ICU admission, or death. Investigators stopped the study early due to futility.

- CORIMUNO-19-TOCI-1 (n=131): Two endpoints were of primary interest — scores higher than 5 on the WHO 10-point Clinical Progression Scale (WHO-CPS) on day 4, and survival without need of ventilation (including noninvasive ventilation) at day 14. Tocilizumab did not demonstrate efficacy on the first measure and “might” (I quote the paper) have reduced the need for mechanical ventilation (results were borderline). No impact on mortality.

- BACC Bay Tocilizumab Trial (n=243): Unlike the first two, this was a placebo-controlled trial, with a 2:1 randomization to tocilizumab or placebo. Tocilizumab did not significantly reduce the requirement for intubation or mortality, the primary endpoint. Since the confidence intervals around the point estimate for benefit or harm were wide, the study could not exclude either one.

- EMPACTA (n=389): Also placebo-controlled, this study’s primary endpoint was death or mechanical ventilation by day 28. Here, tocilizumab did reduce the risk for mechanical ventilation, but mortality at day 28 was not improved — strangely, it was numerically higher with the treatment (10.4% vs 8.6%). (The study is not yet peer-reviewed.)

If that’s not enough, a September press release on the largest randomized study — COVACTA, with 450 participants — did not meet its primary endpoint of improved clinical status nor the secondary endpoint of reduced mortality.

What can we glean from this flurry of study results? I agree with this excellent review by Dr. Jonathan Parr, who wrote that the findings “do not support routine tocilizumab use in COVID-19.”

Oh well. Time will tell whether any secondary benefits from this targeted and powerful immunosuppressive accrue, but given its extremely high cost and potential adverse effects (including increasing risk of infection), we should not be using tocilizumab in routine clinical practice for COVID-19.

But at least we’ll soon have monoclonal antibodies, right? Well, monoclonal antibodies are promising — but if they work, and if so in what patients, both remain unclear.

What does appear clear is that the monoclonals in late-stage clinical trials — being developed by the companies Lilly and Regeneron — don’t improve outcomes in severely ill hospitalized patients. First, the NIH halted the study of LY-CoV555 in this population:

The Data Safety Monitoring Board reviewed data from the ACTIV-3 trial on Oct. 26, 2020 and recommended no further participants be randomized to receive LY-CoV555 and that the investigators be unblinded to the data. This recommendation was based on a low likelihood that the intervention would be of clinical value in this hospitalized patient population.

This followed an action-pausing enrollment in that study for a possible safety issue, but ultimately, the decision stemmed from a lack of benefit, also known as a futility analysis. Importantly, study of LY-CoV555 continues in outpatients with COVID-19, who may yet benefit as evidenced by a reduced need for hospitalization in the phase 2 study.

Next, Regeneron announced it had halted its own study of REGN-COV2 (an antibody “cocktail”) in patients requiring high-flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation, citing both a lack of efficacy and a potential safety concern. Could “immune enhancement” be playing a role? The trials of this treatment in other patient populations continue.

If REGN-COV2 rings a bell, that’s because it’s one of several therapies given to the president during his stay at Walter Reed Medical Center. It’s also part of the larger RECOVERY study conducted in Britain, and these negative results will prompt a data review by the study’s independent Data Monitoring Committee.

So neither antibody treatments worked in the more severely ill COVID-19 patients. And if they end up as promising treatments for milder disease — and I hope they do — imagine the logistical hurdles required to administer these intravenous therapies to outpatients with COVID-19. The mind boggles.

Let’s finish with the latest discouraging newsflash on COVID-19 immune-based therapies, this time with anakinra, the interleukin-1 (IL-1) inhibitor:

Same story again for #COVID19 drug claims:

* an open-label single arm study with "matched control" (à la Raoult) claims mortality reduction with anakinra (NCT04357366)

* French ANSM sets the RCT testing anakinra on hold for a death imbalance in anakinra arm… (ANACONDA-COVID-19)— Bertrand Delsuc (@BertrandBio) October 30, 2020

The halted study — yes, called ANACONDA — compared anakinra versus optimized standard of care in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. It was open-label, with a planned enrollment of 240, and a primary endpoint of “being alive and not requiring any invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).”

And now it has been halted due to excess mortality in the intervention arm. Ouch — the worst possible outcome. More details to come.

How about the favorable observational studies?

As with tocilizumab, these data can be highly misleading, even when explanatory models show that the treatment should work. Our brains have a tendency to make up scientific rationales for treatments that we want to work, it’s just something we can’t help doing. Such instincts are stronger than our ability to identify and control for all potential confounders.

As for these disease models, let’s remember that the immune system is oh so complicated — at its best, fine-tuned to protect us from pathogens, but not so strong as to cause uncontrolled autoimmune disease.

Just like we can’t open up a broken computer and disconnect random wires or remove various circuit boards to fix it, we can’t selectively suppress the immune system and expect favorable outcomes when treating a new disease. Which is why, ultimately, all of these treatments need data from controlled clinical trials before they can be broadly adopted.

It’s hard work, and it takes time, but it needs to happen.

October 25th, 2020

(Not) Attending Professional Meetings in the COVID-19 Era

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), our professional society, held its annual meeting this week, IDWeek.

As usual, I registered for and attended the meeting.

Of course I should have written “attended” the meeting, as instead of having an in-person meeting in Philadelphia (the original planned venue), it was entirely done online. Another “virtual” meeting due to COVID-19.

First, the good news. The preparation and content both were top-notch. Navigating the site, watching the presentations either live or on-demand, and reviewing the posters, I found the experience transparent and bug-free. (No pun intended.)

Happy to report there has been real progress in the virtual meeting user interface since the last conference I “attended”.

And there is gobs and gobs of content. (Or should that be “are gobs and gobs” — inquiring minds want to know!)

That’s the great thing about IDWeek — there’s so much to hear about that you eventually finish the meeting having learned a ton. The top experts in our field weigh in on what they’re experts about –what could be better? It’s especially useful when stepping outside one’s comfort zone.

Now, the not-so-good news — these online meetings can’t come close to replicating the experience of having them live.

To be sure, big in-person work meetings are far from perfect. They’re expensive, require travel (the agonies of which are legion), use up our carbon footprint, and gosh they are tiring from the socializing perspective. Sometimes you just want to sit in your hotel room and hide, and watch the major oral presentations and read the posters online.

Understandably, some doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and other clinicians wouldn’t consider attending these meetings. Too time-consuming and expensive.

But you know what? Doing only the online part misses a lot of what’s great about live meetings. When attending them, you can focus on the meeting, mostly free of the distractions of work and home.

I spent most of last week at work, well, working.

This is very cool. And beautiful! But given my distraction during #IDWeek2020 — you know, with clinic, epic messages, doodle polls, manuscript reviews, slide deadlines (with *learning objectives*), on-line learning modules, zooms, etc, I'm probably this dot way out here. pic.twitter.com/4dkf7C4nh0

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 25, 2020

Periodically last week, I’d remember that IDWeek was in fact still taking place — and then I’d have the double hit of guilt coming from both getting behind in work and the FOMO of not “being” at the conference. Yikes.

One colleague fought this problem by posting this:

Thank you for your email. I am attending a virtual conference, and will not be checking email until October 25. I will respond to your message as soon as possible.

Gives a new meaning to the term, “out of office message,” doesn’t it?

Furthermore, IDWeek in particular always has great community feel to it — these are our people. Really missed that.

What a great chance to network and reconnect. A clump of former ID fellows, now having launched their careers, gathers by a poster — how fun to catch up! A friend/colleague from New York or Los Angeles or Miami or Chicago or Philadelphia or Madrid or Sydney I’d not seen since the last conference — how are you? A person who’s recently made a big splash with a research paper, or a promotion, or by landing a big new job — congratulations!

And the personalities! Here are a few famous ones from my HIV world: Carlos del Rio somehow knowing literally everyone in our field — how does he do that? Jeanne Marrazzo’s enthusiastic and supportive laugh. Joe Eron steps up to the microphone, and asks the most incisive post-presentation questions. John Bartlett with his yellow note pad, sitting in the front row capturing every pearl. (Dating myself a bit with that last one.)

No, canceling in-person academic meetings isn’t the biggest loss dealt us by the COVID-19 pandemic, far from it.

But it’s a loss nonetheless.

October 18th, 2020

Does Remdesivir Actually Work?

Quick answer — it’s complicated.

Let’s start with a clinical anecdote — rightfully considered the weakest form of evidence, yet paradoxically holding great power over us because we’re imperfect humans. It’s the way we’re wired.

In April, a patient of mine with stable HIV came into the hospital with COVID-19 pneumonia. (Certain details changed for privacy.)

She works cutting hair, in a community hard-hit from the pandemic and where mask-wearing was inconsistent. She knew as soon as she developed fever, chills, and back pain that this is what she had.

She must have had symptoms for no more than 36 hours when she arrived at the hospital, and because she has HIV (who knew whether this worsened outcomes?) and is quite overweight, she was admitted.

She enrolled in the SIMPLE study — which compared remdesivir for 5 or 10 days to standard of care, all open-label — and was randomized to the 5-day course. She received her first dose of the drug the night of admission.

Again, she had been symptomatic for no more than 2 days.

The next day, she looked like a new person. Her fever was down, she was breathing more easily, and she told me her back pain went away as soon as the first dose had completed its infusion. She left the hospital on day 3, and made a complete recovery.

Of course, she could have recovered just as quickly without remdesivir — that’s the problem with an anecdote.

But based on this and other cases I saw — and the extensive experience of my indefatigable colleagues Dr. Francisco Marty and his team, who enrolled dozens of patients into this study — I was not surprised when in May, a different and more rigorous remdesivir clinical trial reported significantly faster recovery in the treatment arm than in the controls.

And because this study — called ACTT-1, now with final results — included a placebo arm and was blinded, this provided much stronger evidence that remdesivir actually works. (That’s in the title of this post.) It worked particularly well in people with shorter duration of symptoms and in those requiring oxygen. It didn’t help people so sick that they needed mechanical ventilation or ECMO.

When the data from ACTT-1 became available, we created a construct about these critically ill patients who didn’t benefit from remdesivir. In this view, they were in the immune phase of the illness, where the body’s immunologic response to the infection drove more disease than viral replication.

We can’t expect an antiviral to control these processes. Just like oseltamivir or baloxavir for influenza, you have to act early with remdesivir when treating SARS-CoV-2. Let dexamethasone or some other immunomodulator do the late work.

See, it all fits together perfectly.

But there were always holes in this neat little package.

First, the original remdesivir study from China showed no benefit of treatment. Yes, it was underpowered due to dropping case numbers, but the drug didn’t lower viral loads in recipients either. Concerning.

Second, the open-label study my patient enrolled in had a funny result in the 10-day arm — no apparent benefit compared with standard of care. (The 5-day arm did show benefit.) How do we explain that?

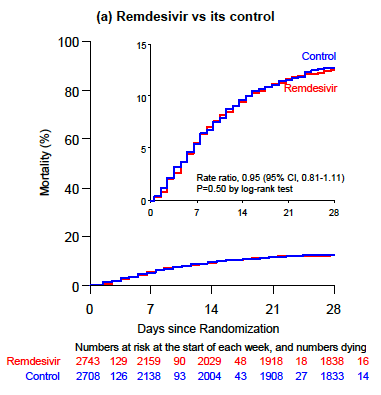

Now we have the interim results of the SOLIDARITY study, at least in preprint form, and that neat little package has even more holes.

In SOLIDARITY, over 11,000 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (from 405 hospitals and 30 countries) were randomized between whichever study drugs were locally available and open control. This included up to five options — four active treatments versus local standard-of-care. The drugs were lopinavir/ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine (remember those?), interferon beta-1a, or remdesivir.

(Based on the limited availability of some of the drugs across countries, the study arms differed in size.)

The results for all the interventions failed to show a survival benefit. And the survival curves for the remdesivir arm versus standard of care look depressingly the same:

You could barely draw curves that overlap so precisely. This figure has been emblazoned on the retinas of ID clinicians since the preprint was released last week.

You could barely draw curves that overlap so precisely. This figure has been emblazoned on the retinas of ID clinicians since the preprint was released last week.

So how do we explain these discordant results? We can’t do so completely given the different study designs and populations. But just as how ACTT-1’s benefits can’t overrule the SOLIDARITY results, nor can SOLIDARITY negate ACTT-1 or the 5-day results from SIMPLE.

So let’s put all the studies together, as shown here in this colorful meta-analysis, and exclude patients who are on mechanical ventilation since no study demonstrated benefit in this population:

https://twitter.com/mikejohansenmd/status/1317056317522169856?s=20

First, we’ll note that SOLIDARITY’s much larger sample size trumps (ouch) the other studies. Second, the point estimate just crosses 1 (no benefit), but falls to the left of the line, suggesting (if you squint) some benefit.

If I had to postulate where we’d see the greatest benefit for remdesivir, it would be in patients with shorter duration of symptoms. Even in the negative underpowered study from China, those with fewer days of illness did better than controls. Could it be that the favorable results in ACTT-1 were from the fact that 25% of patients were enrolled with symptoms for 6 days or fewer?

Related, SOLIDARITY began enrollment in March, and for much of the enrollment period, patients with COVID-19 did everything they could to avoid hospitalization. For many, I suspect the short window of time for this antiviral to benefit had closed by the time they were admitted. Duration of symptoms is not reported in the preprint, a critical piece of information.

So for now, the answer to the question, “Does remdesivir actually work?” is a cautious maybe. Sometimes. For some people.

Which, given the absence of anything else right now and its low toxicity, means I’d still recommend it for most hospitalized people with COVID-19 — with the hope of giving it sooner rather than later, especially for those on oxygen at high risk for disease progression.

But if we can learn anything from the mental gyrations required to square these conflicting study results, it’s that we definitely need more effective options.

October 12th, 2020

“Dying in a Leadership Vacuum” — Defended

This past week, the Editors of the New England Journal of Medicine published a piece entitled “Dying in a Leadership Vacuum.”

This past week, the Editors of the New England Journal of Medicine published a piece entitled “Dying in a Leadership Vacuum.”

It’s a scathing indictment of the United States government’s response to COVID-19, in particular our inability to have a science- and evidenced-driven approach to control a disease that has now killed more than 215,000 Americans.

One might ask what purpose such an editorial serves. After all, those who agree with the sentiment (raises hand!) already know, less than a month before election day, how we’re going to vote.

And those who disagree will dismiss its publication as politics as usual.

Never mind that our government’s first comprehensive pandemic response program was started by a Republican president, George W. Bush. The same president who launched the largest global HIV treatment program in history, the President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

There’s hardly an ID specialist out there who didn’t strongly support these important initiatives. So no, this isn’t all about politics.

Another criticism of the editorial, say some doubters, is that it could have the paradoxical effect of driving voters away — confirmation that doctors and scientists are elitist intellectuals with a liberal bias.

In short, it does little more than “making the writers feel good.”

There is perhaps some validity to this perspective — I was accused of the same when writing an imaginary “apology” issued by the president. (Somehow we never heard from him — no surprise.). But it did make me feel better, so guilty as charged on that account.

But still — are there other benefits to such an opinion piece?

I’d say yes. An important counter view is that a pointed editorial from the usually apolitical New England Journal of Medicine signals the severity of the problem we have. Saying nothing would arguably be a political stance as well.

The piece also acts as a convenient way to catalogue some painful data, and highlight our more egregious mistakes. It’s well-written, and accurate, and already has been read over 2 million times. But if you don’t have time to read the whole thing, here are some choice selections.

First, some damming mortality statistics:

The death rate in this country is more than double that of Canada, exceeds that of Japan, a country with a vulnerable and elderly population, by a factor of almost 50, and even dwarfs the rates in lower-middle-income countries, such as Vietnam, by a factor of almost 2000.

Next, our ongoing testing and PPE fiascos:

When the disease first arrived, we were incapable of testing effectively and couldn’t provide even the most basic personal protective equipment to health care workers and the general public. And we continue to be way behind the curve in testing. While the absolute numbers of tests have increased substantially, the more useful metric is the number of tests performed per infected person, a rate that puts us far down the international list, below such places as Kazakhstan, Zimbabwe, and Ethiopia, countries that cannot boast the biomedical infrastructure or the manufacturing capacity that we have.

Our inability to support coherent social policies:

Our rules on social distancing have in many places been lackadaisical at best, with loosening of restrictions long before adequate disease control had been achieved. And in much of the country, people simply don’t wear masks, largely because our leaders have stated outright that masks are political tools rather than effective infection control measures.

How about our usually capable and non-partisan government agencies?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which was the world’s leading disease response organization, has been eviscerated and has suffered dramatic testing and policy failures. The National Institutes of Health have played a key role in vaccine development but have been excluded from much crucial government decision making. And the Food and Drug Administration has been shamefully politicized, appearing to respond to pressure from the administration rather than scientific evidence.

And now, the big finish:

But this election gives us the power to render judgment. Reasonable people will certainly disagree about the many political positions taken by candidates. But truth is neither liberal nor conservative. When it comes to the response to the largest public health crisis of our time, our current political leaders have demonstrated that they are dangerously incompetent. We should not abet them and enable the deaths of thousands more Americans by allowing them to keep their jobs.

So there’s hope — and it comes on November 3.

Until then, we have dogs, and The Beatles.

October 4th, 2020

Does the White House Outbreak Invalidate the Strategy of Frequent Testing for COVID-19 Control?

As I’ve written here many times, I’m hopeful that frequent, inexpensive, rapid home testing for COVID-19 will help us climb out of this pandemic mess.

Let’s name it the Mina Frequent Testing Plan, after my indefatigable colleague Dr. Michael Mina who has championed it for months — most recently in a perspective published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

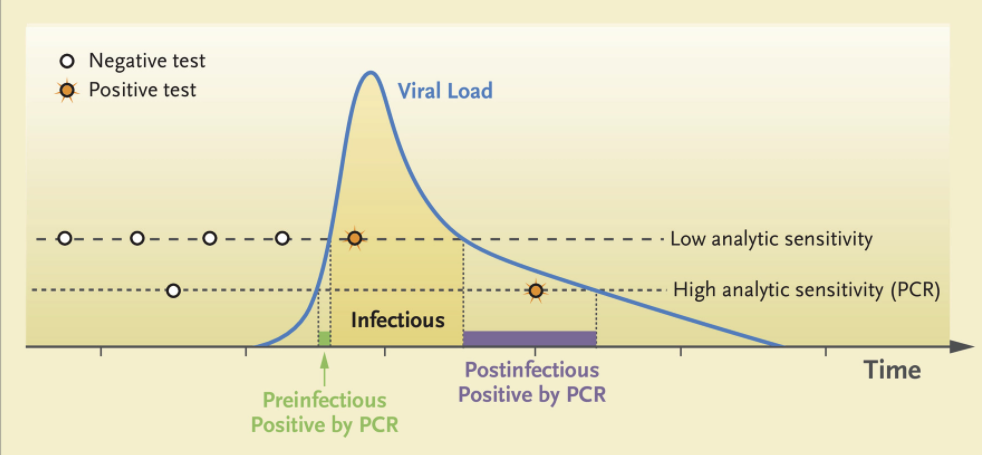

For the Rip Van Winkles out there, here are the basics of this approach:

- Much of the community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 comes from people who don’t know they are infectious since they have no or few symptoms.

- Testing them using standard PCR tests is impractical — too slow, expensive, and difficult to access.

- Scientists and companies have collaborated to develop simple paper-based rapid tests done on saliva samples.

- Results return in 15-30 minutes and require no special instruments for interpretation — analogous to home pregnancy or HIV tests.

- Produced at scale, the tests are cheap and readily available — $1-5 each.

- These tests pick up some people who have high levels of infectious virus but are either asymptomatic or presymptomatic — hence potentially contagious to others but otherwise unaware themselves. Now, none of these people are being detected.

- Once they have a positive test, they isolate at home — they don’t go to work or school. Tests would be confirmed using standard PCR.

- Individuals can also buy them for use at home.

- Schools, hospitals, nursing homes, food service companies, places of worship, and others can purchase them in bulk, with requirements for a negative test (even better, a series of negative tests over the previous several days) for entry.

The strategy has a growing number of advocates across the medical, scientific, and public health fields — including the FDA — which is exciting. Here’s a short white paper on the topic many of us have helped draft, with a focus on testing in schools.

But as the Mina Frequent Testing Plan drew sufficient attention, various criticisms appeared, in the press and on social media. (Here’s a skillful rebuttal.)

These negative views certainly raise important concerns. I worry in particular about false positives — they will be inevitable when doing high-volume testing on a low-prevalence population.

Now, we have a president who acquired COVID-19 despite the fact that he and those who surround him are tested often.

How did this happen? Is this the death knell of the Mina Frequent Testing Plan?

The obvious first explanation is that no test is perfect. The rapid antigen tests used by the White House will miss some people who are infectious. Of particular concern are those who get tested only once, right before meeting the president.

The math is simple — if you increase the number of visitors, you increase the chance that at least one person with infection will escape detection with a single rapid test.

Remember, one strength of the Mina Frequent Testing Plan is just that — it’s frequent! People who test negative in the early phase of infection will test positive with tomorrow’s or the next day’s test based on the kinetics of viral replication in someone who has just come down with the disease.

From Mina’s NEJM piece, here are those viral trajectories — a person with a negative test in the morning could potentially be infectious shortly thereafter:

With the many visitors to the White House on Saturday, September 26 — the day the president announced the nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court — only a single rapid test granted them access to the event, mask-free.

Also, let’s remember that testing won’t give us a free pass to behave as if we were living in the Before Times, again because testing isn’t perfect. Certain activities facilitate spread of the virus — crowds, close conversations, poor ventilation.

How about this for an example?

At least 7 people who attended ACB's nomination ceremony in the Rose Garden on Sep. 26 have since tested positive for coronavirus. But experts say the more risky time spent that day was at a reception inside the White House. Here are some scenes. https://t.co/mTsZsxmSfy

— Christiaan Triebert (@trbrtc) October 3, 2020

Ouch.

Or this?

Double ouch! Watching that video makes most of us ID clinicians feel like we’re living on another planet. Suspect many of you readers feel the same!

In summary, let me quote my Boston ID colleague Dr. Roby Bhattacharyya, who wisely wrote:

People tap-dancing prematurely on the grave of rapid testing should reflect on how remarkable it is that for people behaving this way all year, indoors and out, in a place with countless thousands of visitors, it took until October for a superspreading event to happen. Test more.

So yes, the Mina Frequent Testing plan lives on — even if the track record of keeping the president free of the virus does not.

Which teaches us more about the limits and vagaries of human behavior than it does the limits of testing, doesn’t it?