An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

January 25th, 2009

Just Twenty Days Until Pitchers and Catchers Report …

As the temperature in Boston again falls below 10 degrees, my thoughts longingly turn to baseball — and how a locally unpopular team is making a foray into the world of Infectious Diseases:

As the temperature in Boston again falls below 10 degrees, my thoughts longingly turn to baseball — and how a locally unpopular team is making a foray into the world of Infectious Diseases:

The potential of a serious staph infection affecting a member of the team has not been lost on the New York Yankees. According to a provider of disinfecting sports coating, the Yankees have been proactive in their quest to keep the new stadium as clean as possible.

“Of course they want to protect their investments, but they also want to minimize any bacterial infection anywhere in the new stadium to protect the fans,” said Craig Andrews, CEO of CSG Sportscoatings. “They are the most proactive of any organization in Major League Baseball in protecting their facilities for players and fans.”

Andrews said all public bathrooms and concession areas, along with the home and visiting clubhouses, weight rooms, lounges, showers, coaches’ rooms, dugouts and bullpens, are being treated.

Whether these coatings actually work is open to debate — regular cleaning of surfaces with detergent-based cleaners or disinfectants seems most important in locker rooms — but regardless, I can just hear it now.

Yankee fan: “Great, now Texeira, Sabathia, Jeter, and A-Rod can stay healthy.”

Red Sox fan: “This will probably spawn the super-bug that will end civilization.”

Football fan: “Who cares?”

January 22nd, 2009

Fear of Vaccines: Not Just Parents

Fear of vaccines are legion among many parents, with enormous public health resources devoted to defusing this fear and trying to debunk common myths. I find this site particularly useful.

(Talk about a “hot button” topic. Read this to get an idea about how passionate views on vaccine safety can be. Wow.)

This fear, however, isn’t limited to parents. With the updated adult immunization schedule just released, I thought I would share a recent e-mail I received from a very experienced internist:

A man with nasal polyps on inhaled steroids regularly, requests Zostavax. Would you counsel avoiding the injection out of concern for him developing disseminated zoster with the vaccination, or is this not a concern? Would the vaccine have any effect on the likelihood of lung cancer recurrence, which was surgically resected last year?

The answer to the first question is easy — no. (Guidelines here, reviewed by me here.)

But the second question? Why would someone worry that the zoster vaccine would cause a relapse of cancer? Is there yet any biologic or epidemiologic data that could possibly link immunization with cancer recurrence or progression?

Yet if the vaccine is given, and the cancer then recurs, will the patient — and his doctor — connect the two?

One of the first lessons in Statistics 101 is that correlation does not mean causation. But boy this is a hard lesson to learn.

January 17th, 2009

Salmonella, CDC, and How to Prevent a Cold

Today’s ID/HIV Link-o-Rama is being brought to you from the frozen tundra of Boston, MA:

Today’s ID/HIV Link-o-Rama is being brought to you from the frozen tundra of Boston, MA:

- This past summer’s salmonella outbreak that sickened more than 1000 people was linked to raw jalapeno and serrano peppers. In the current one, the suspected culprit is contaminated peanut butter. Aside from the fact that raw hot peppers and peanut butter in a jar are both uncooked, I can hardly think of any two foods as being more dissimilar. (“Would you like some hot salsa with your peanut butter?”) Count food safety as one of the formidable challenges for the newcomers to the FDA (along with perhaps updating their clunky web site).

- Another government-agency transition will be taking place at the CDC, as current chief Julie Gerberding will be stepping down. (Can’t seem to find this info on their now-excellent site — maybe waiting for the official day, Jan 20 2009.) Her tenure will be forever linked to her strong position during the anthrax attacks of 2001, which led to her subsequent appointment — plus charges that she softened her position on global warming to match that of President Bush. And there was a notable appearance in this famous Journal of Epidemiology.

- The pneumococcal vaccine has significantly reduced cases of pneumonia in infants, and meningitis in both children and adults. The current rate of pneumococcal meningitis is 0.79 case per 100,000 persons, confirming what I always tell our ID fellows — that bacterial meningitis is a rare entity indeed, so it’s no wonder we are consulted on virtually every case. It doesn’t matter that choosing the right antibiotic is usually easy; these cases are terrifying.

- Add a reduced risk of colds to the (long) list of benefits associated with a good night’s sleep. Study volunteers (yes, people volunteered for this) were 3-fold more likely to get a cold after a rhinovirus challenge if they slept less than 7 hours a night. I am not by nature one of those paranoid ID doctors who believes that the world is filled with nasty micro-critters just waiting to strike — in fact, I’m relatively laissez-faire on most ID-related issues. (Eating in Mexico City, for example.) However, I’m terrified of colds (am convinced the severity of colds is proportional to nose size) and can think of few greater motivations for getting enough sleep than this latest research.

- Speaking of cold — cold weather, that is — the high temperature in Montreal yesterday was -4.0 degrees Fahrenheit. As I write this, it is a comparatively balmy 1 degree above zero. Say what you will about the CROI organizers, they are a hardy bunch. This year’s meeting should make those Februaries in Chicago seem like a trip to the Caribbean.

Stay warm!

December 31st, 2008

Free Antibiotics!!!

Yes, the northeast supermarket/pharmacy chain Stop & Shop will now offer antibiotics — for free.

(And they are not the first. Take a look at this amazing advertisement.)

Says Stop & Shop’s “consumer advisor” Andrea Astrachan:

Stop & Shop pharmacies are committed to improving the health and wellness in our communities during the winter season when families are susceptible to coughs, and certain cold-related [emphasis most definitely mine] and bacteria-borne illnesses. As the provider of fresh, wholesome foods that help our customers stay healthy, we feel it is equally important to offer these free antibiotics to fight illness.

Fresh food linked with free antibiotics! What would Michal Pollan say?

And call me cynical, but could it be that someone looked at the profit margins on generic amoxicillin compared with, say, your typical cough/cold remedy, and thought … “Hey, if we can get them here for our free antibiotics, maybe they’ll grab some NyQuil, and some Tylenol PM, and some Tenzaprine AQ …”

(I made “Tenzaprine AQ” up. Not bad, eh?)

The list of free antibiotics is here — not much of a surprise what’s included, as all are widely-used generics. (Sorry, no linezolid.) And it should be noted that ciprofloxacin’s stock seems to have fallen almost as far as Enron’s.

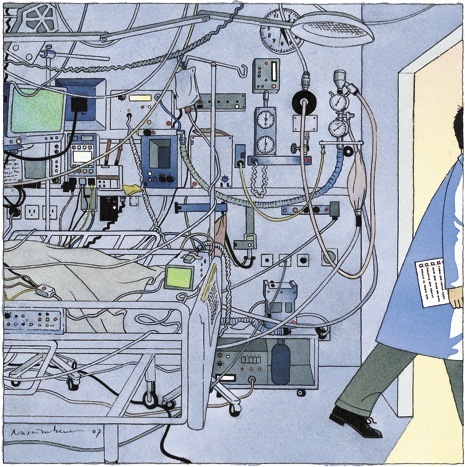

Of course in many situations the generic antibiotic is the right one to use, and I’m sure the consumer will appreciate this $10 or so savings off the pharmacy bill. But if ever there were a time to bring out (again) this wonderful New Yorker cartoon, this is it!

December 29th, 2008

Required Reading: Introducing the “iPatient”

Many HIV/ID specialists first heard of Abraham Verghese from his book My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story, which was published in 1994. He told us what it was like to be a newly-minted ID doctor, thrust into treating the first cases of HIV/AIDS in a remote town in Tennessee during the mid-1980s.

Compelling stuff — I thought the book was terrific. (And apparently I’m not alone, as I’ve received it as a gift no fewer than 3 times.)

In this week’s New England Journal of Medicine, Verghese has a wonderful perspective piece on a phenomenon that will be all-too familiar for doctors working in academic medical centers:

On my first day as an attending physician in a new hospital, I found my house staff and students in the team room, a snug bunker filled with glowing monitors. Instead of sitting down to hear about the patients, I suggested we head out to see them. My team came willingly, though they probably felt that everything I would need to get up to speed on our patients — the necessary images, the laboratory results — was right there in the team room. From my perspective, the most crucial element wasn’t.

What follows is a beautiful description of the tension between the “traditional” ways of clinical medicine — which involve taking real histories and doing actual physical exams — and the new way, which uses in place of the real patient “an entity clothed in binary garments: the iPatient.” And what’s wrong with treating the iPatient?

Pedagogically, what is tragic about tending to the iPatient is that it can’t begin to compare with the joy, excitement, intellectual pleasure, pride, disappointment, and lessons in humility that trainees might experience by learning from the real patient’s body examined at the bedside. When residents don’t witness the bedside-sleuth aspect of our discipline — its underlying romance and passion — they may come to view internal medicine as a trade practiced before a computer screen.

Even if you don’t believe in his premise — that something is lost when “the iPatient’s blood counts and emanations are tracked and trended like a Dow Jones Index” — this is a nifty bit of medical writing. You’ll find here none of the sanctimony such pieces often have (“in my day, we spun our own hematocrits, and were the better for it …”), just common sense about the potential consequences of focusing more on the computer screen than the person being treated.

Highly recommended.

December 23rd, 2008

Flu Resistance to Oseltamivir: The Bugs Win Again

I must admit, the recent report that 49 of the 50 H1N1 flu viruses tested by the CDC are resistant to oseltamivir caught me by surprise. For the non-math majors among the readership, that’s a 98% resistance rate. Yikes.

I must admit, the recent report that 49 of the 50 H1N1 flu viruses tested by the CDC are resistant to oseltamivir caught me by surprise. For the non-math majors among the readership, that’s a 98% resistance rate. Yikes.

Actually, the rate of resistance is so high that at first I didn’t believe it when my wife told me — thought she’d flipped the numbers. “You mean that 1 of 50 was resistant,” I insisted — wrongly. As usual, the pediatrician has the accurate news on the latest outbreak — I should have learned that long ago.

So … what happened? Last year the resistance rate was only 10%, and it’s not as if since then we’ve put oseltamivir in the drinking water. The bulk of people with influenza never get diagnosed or treated, so it can’t be due to excessive prescribing on the part of clinicians. I doubt there’s much in the way of off-label or illicit use, and certainly nothing like this is showing up in my spam filter:

Brand name T-A-M-I-F-L-U cheap! From bestcanadapharmacy.com

One smart virologist I know suggested it might be the result of preventive programs in nursing home-type settings during flu outbreaks. These preventive treatments can go on for weeks, so if the resistant viruses have any sort of evolutionary advantage, they could become the dominant strain.

For now, interim guidelines for management of patients with influenza are available here. We’ll be using zanamivir (must be the best name for an antiviral ever — too bad it can’t be used in kids or patients with asthma), and our old friend rimantadine — though this latter drug has no activity against influenza B, and of course H3N2 viruses are already likely to be resistant.

Or we’ll be using nothing but TLC, which is kind of where we were several years ago. And chalk another one up for the bugs, they are (in aggregate) pretty darn smart.

December 19th, 2008

Infectious Disease in the ICU: Help Please? Part I

I am currently attending on the inpatient service, which means I spend a good chunk of my day seeing new ID consults and rounding on follow-ups. As I’m sure is true in most hospitals, many of these consults are from the intensive care units (ICUs).

After 18 years in this ID business, I confess I still find myself quite challenged by ICU Infectious Diseases. It’s not due to the complexity of the cases, in fact just the opposite — paradoxically, there’s a sameness to the cases that is worlds away from the wonderful variety of ID/HIV elsewhere: the outpatient with fever of unknown origin, or the inpatients with endocarditis, meningitis, orthopedic infection, HIV-related complication, or tropical fever (the stuff that makes up much of the rest of the consult volume). One intensivist says that once patients get past the first few days after admission, most of the medical issues they face are similar.

From the ID perspective, this means “rounding up the usual suspects,” including searching for line infections, UTIs, C diff, sinusitis, pancreatitis, surgical site infections, acalculous cholecycstitis, drug fever, infected pressure ulcers and — especially — nosocomial pneumonia.

There’s a sameness to these investigations that makes individualizing care difficult, and often forces us to focus on the (abundant) microbiologic data as distinguishing characterisitics. Just how resistant are the bacteria isolated from this patient’s respiratory sample? How many different possible pathogens can be cultured from a surgical drain? What is the significance of candida isolated from several non-sterile sites? How about those few colonies of coagulase negative staph on a removed line tip?

So where to go for help? For a comprehensive “how to” for this patient population, check out the recent IDSA/American College of Critical Care Guidelines. It’s an impressive document.

And give yourself plenty of time — it’s 20 pages long, and has over 200 references.

(In Part II, the issue of empiric antibiotics in the ICU.)