An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

July 1st, 2010

RFA-AI-10-009, HIV Cure, and “Berlin Patient” Update

Interesting “RFA” (Request for Application, #RFA-AI-10-009) from Bethesda:

Interesting “RFA” (Request for Application, #RFA-AI-10-009) from Bethesda:

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institutes of Health (NIH), encourage grant applications from institutions/organizations to address the problem of HIV-1 persistence in HIV-1-infected persons treated with suppressive antiretroviral drug regimens… The goal of this initiative is to expand the knowledge base on HIV-1 latency and persistence so that eradication strategies can be designed, developed and evaluated.

In other words, research directed at a cure. If there’s any doubt about what the ultimate goal of the grant is, the title of the RFA is “Martin Delaney Collaboratory: Towards an HIV-1 Cure (U19)”, named in honor of the influential patient advocate who died last year.

I’ve written before about the “Berlin Patient” (here and here, for example) who, after receiving a bone marrow transplant from a donor homozygous for the delta-32 CCR5 mutation, was able to stop all antivirals without experiencing virologic rebound. The latest on him from the “cure” perspective is that even Bob Siliciano’s lab can’t find virus in the guy:

As of today, [the Berlin patient] remains healthy, and his HIV levels are undetectable … Even samples sent to Siliciano’s lab and other U.S. facilities that have the most sensitive assays have come up empty. Says Siliciano: “I think he’s cured.”

From single case report — one that began with an obscure research poster at the 2008 Retrovirus conference — to a complete cure of HIV, this case must be showing us the way to eradicate the virus.

And if you’d asked me ten years ago which I thought we’d see first, a truly effective HIV vaccine or a legitimate pathway to an HIV cure, I’d definitely had said the vaccine.

Now I’m not so sure …

June 23rd, 2010

Combined HIV Antibody/Antigen Test Approved

From the FDA:

From the FDA:

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today approved the first assay to detect both antigen and antibodies to Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)… The highly sensitive assay is intended to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of HIV-1/HIV-2 infection, including acute or primary HIV-1 infection. Since it actually detects the HIV-1 virus (specifically the p24 antigen) in addition to antibodies to HIV, the ARCHITECT HIV Ag/Ab Combo assay can be used to diagnose HIV infection prior to the emergence of antibodies.

This is definitely progress, as it seems fairly obvious that combined antibody/antigen detection is how we should optimally be diagnosing HIV infection.

The fact remains that despite the increased sensitivity of antibody testing, some HIV cases are still missed when patients present with recently-acquired infection, too soon after viral transmission to have detectable antibody. One acute case we saw recently had reactive ELISA, but a completely negative Western blot — anecdotally this is becoming an increasingly common “negative” HIV test since ELISA has cranked up the sensitivity so much.

The two settings where this new test might be particularly useful are in high-prevalence populations (where the incidence is higher) and when people seek testing soon after a risky exposure.

Remaining questions include the cost of the new assay (both in literal terms and in lab personel resources), the predictive value of a reactive result in low risk settings, and how the p24 antigen here compares in sensitivity with HIV RNA measurement (our usual way of detecting acute HIV). On the last issue, at least one past study suggested that p24 was less sensitive than HIV RNA, but that was a long time ago.

(FYI, June 27 is National HIV Testing Day. Apologies for the grammatical error — “a HIV test” — in the above image, I love the poster.)

June 16th, 2010

Another HIV Drug Development Program Bows Out

Last month, Avexa announced that they will not be going forward with their development of the investigational NRTI apricitabine.

Last month, Avexa announced that they will not be going forward with their development of the investigational NRTI apricitabine.

Now Myriad says its program to develop bevirimat is closing as well.

The problems with these drugs — twice daily dosing with apricitabine, formulation and mixed responses with bevirimat — are not the real story here, since arguably we have overcome these hurdles with investigational drugs before.

Nope, the real issue here is that the challenge of HIV drug development has become staggeringly high due to the very success of our current therapies. Who wants to spend the resources on therapies for drug resistance when hardly anyone fails treatment anymore?

Which leaves me wondering: what are we going to do with that small population of patients who have literally no drug options? The group with NRTI, NNRTI, PI, enfuvirtide, and integrase resistance who have dual-mixed tropic virus?

Time for “orphan drug” status for investigational HIV drugs that meet this need? Certainly some sort a national collaborative effort would be welcome, as most practices have very few of these unfortunate patients.

June 11th, 2010

Plays at the (Culture) Plate

Some quick ID/HIV/other thoughts while we marvel in all that is Strasburgian:

Some quick ID/HIV/other thoughts while we marvel in all that is Strasburgian:

- Did you know that HIV medication adherence improves over time? So much for “pill fatigue.” By the way, this anecdotally fits with my experience as well. And right now, the biggest reason for patients’ stopping their HIV meds is financial, usually due to loss of or change in insurance.

- This BMJ paper showing that getting an antibiotic in the primary care setting increases the risk of resistance in the person taking the antibiotic should be distributed to every outpatient practice in the universe — and then be prominently posted in waiting rooms.

- More on the underutilized zoster vaccine in the NY Times. Again, from my admittedly warped perspective as an ID doctor — one I’ve already confessed to here — this is one adult immunization not to skip! Biggest barrier? Who’s going to pay the $300 or so for the vaccine. For an example of ironic journalistic juxtaposition, an adjacent piece cites the hundreds (or even thousands) of dollars people might spend on the health of their pet.

- Over on KevinMD, here is a list of suggestions for how to talk to patients while using an electronic medical record. Some good advice — but the bottom line is that something is lost when our attention is split between the patient and the glowing screen. Just think about trying to get your kid’s attention while he/she is on-line. Or vice-versa.

- Want to increase the nasty (as in raunchy) comments auto-posted on your blog? Easy, just include a few choice words in your post’s title. Let’s just say that our spam filter has been busier than usual recently.

Hey, peak Lyme season is here — watch out everyone, hungry ticks are everywhere!

June 2nd, 2010

Screening for Anal Cancer and the World’s Worst Job

In Journal Watch AIDS Clinical Care, we published a simple case: Clinically stable HIV+ gay man, on HIV treatment; anal pap comes back with “atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance” (ASCUS).

In Journal Watch AIDS Clinical Care, we published a simple case: Clinically stable HIV+ gay man, on HIV treatment; anal pap comes back with “atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance” (ASCUS).

What to do with this result? Two experts weighed in, Howard Libman and Joel Gallant. In Howard’s thoughtful response, he acknowledges the limitations of the data thus far, but said he would refer the patient for high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) and biopsy — which is what most of our readers said as well.

But Joel acknowledges that, despite an institutional protocol to refer all such patients, he wavers a bit for those with ASCUS:

I have been bending the rules in patients with ASCUS and monitoring them with yearly Pap smears rather than referring them for HRA. I do this with the understanding that the Pap smear provides an imprecise measurement of the true grade of dysplasia and that those with ASCUS could have higher grades on biopsy. However, I have to weigh that risk with the fact that my patients don’t enjoy going through HRA, biopsy, and ablation, that the parallels between anal and cervical dysplasia aren’t perfect, and that the protocols around anal Pap smear are written without much evidence backing them up.

It’s safe to say that we don’t really know yet what to do — not in this situation, nor in multiple other scenarios involving anal cancer screening.

Just a few questions to ponder: How frequently (if at all) should anal paps be done? If the sensitivity is so poor, why not refer all gay men for HRA/biopsy, skip the pap? Or should it be limited to those with a history of condyloma? (Read this concerning paper.) Or should those patients go right to biopsy? Should HPV testing be done in all patients? What anal cancer screening should be done in HIV-infected women? Or should this just be done in women with cervical disease?

If the evidence were stronger, clearly the Primary Care and OI Prevention Guidelines would recommend a standard screening protocol.

But until then, one hear’s the voice of Joel Palefsky — owner of the “World’s Worst Science Job” — as he highlights the benefits of preventing a common, potentially life-threatening and disfiguring cancer. In response to his (and other’s) work, a diverse range of practitioners out there (PCPs, ID docs, gynecologists, dermatologists, surgeons) now offer high-resolution anoscopy with biopsy for this indication.

But is screening for cancer always the right thing to do?

May 23rd, 2010

Dengue in the News … Again

The recent dengue cases acquired in Florida prompted me to think of two things.

First, is this really a surprise? Dengue has become increasingly common in the Caribbean, the mosquitoes that transmit the virus are widespread in the United States, and it’s not as if there’s some sort of microbiologically (if that’s a word) impermeable barrier between the islands in the Caribbean and our southernmost states:

Add a dose of climate change (not mentioned in the MMWR editorial — just a hunch), and bingo, the perfect recipe for tropical diseases in the Continental 48.

Still, many kudos to the astute ID doctor in Rochester NY who made the diagnosis:

During this third visit [to her primary care doctor], a consulting infectious-disease specialist raised the possibility of dengue infection, despite no recent travel by the patient to a known dengue-endemic area.

Hey, this is why they pay us the big bucks!

The second thing I thought about was another time dengue was the headline in MMWR. Anyone remember the really big news in MMWR when the lead was “Dengue type 4 infections in U.S. travelers to the Caribbean”?

May 18th, 2010

Electronic Medical Records and (LONG) ID Notes

When it comes to writing consult notes, it often seems as if we ID specialists have a blatant form of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Every detail is fair game — travel history, dietary habits, all sorts of seemingly trivial exposures, and of course microbiologic data stretching back to the Cretaceous period.

I’ll never forget receiving sign-out from the graduating first-year ID fellow when I started my fellowship. It included a photocopy of a consult note she had written the day before on a woman with fever after gallbladder surgery.

In five pages of meticulously-detailed prose, there was this memorable item from the Social History:

Two pets at home: a dog (Rusty) and cat (Cleo); both are healthy.

Good news for Rusty and Cleo! But what could this possibly have to do with post-operative fever after gall bladder surgery? Even if you allow that perhaps she was suffering from some bizarre post-cholecystectomy zoonosis (if there is such a thing), why was it necessary to cite the pets’ names?

Electronic medical records have, if anything, made matters even worse for the detail-obsessed. The ability to cut and paste endless reams of data into a note is irresistible to most ID docs.

It leads to a bizarre paradox where the more information in the note, often the less useful it is — a phenomenon expertly dissected over here on the always-interesting KevinMD blog. Says guest writer Jaan Sidorov:

[A doctor] had received a copy of a lengthy consultant-physician’s documentation involving one of his patients and was astonished by the blob of past data, prior notes, test results, excerpts, quotes, interpretations and correspondence that had been replicated word-for-word in the course of “seeing” his patient. The terse portions describing what the patient actually said, what the consulting doctor actually examined and what the diagnosis and plan were were inconspicuously buried toward the end of the EHR document.

And you know what’s most maddening? Under the current “guidelines” for coding and billing, there are true incentives — both financial and regulatory — to write this kind of text-heavy note, one heavily infused with templates and boilerplate language. The more complexity the better!

Here’s a proposal: the goal of a consult note should be concise documentation of what you think, and why, then what you’re recommending, and why.

I’m sure Rusty and Cleo would agree.

May 9th, 2010

Amusing Medical Cartoons … and Humor in Medicine

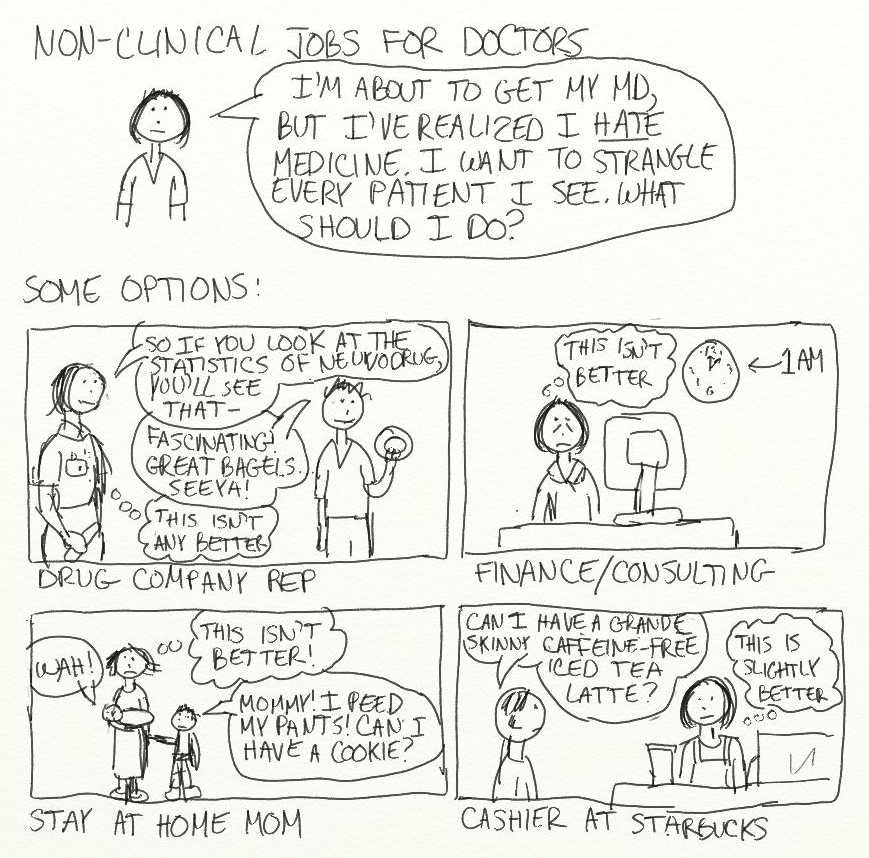

Someone pointed out this cartoon to me.

Someone pointed out this cartoon to me.

What an eloquent depiction of the interior dialogue of a young doctor as she considers various non-medical careers.

Brilliant!

Which led me to thinking more broadly about humor in medicine, about which I quickly remembered that anyone writing about humor (as opposed to writing humorously) will be instantly unfunny.

Sorry.

So let me be brief, and say that I hung around with a bunch of people in college who made cartoons like these their principal means of communication. And that crude art notwithstanding, there’s a real talent to to it.

And most of these are great.

I wonder what she/he (I assume she?) thinks of ID specialists …

The Lancet has

The Lancet has  Over on our Journal Watch AIDS Clinical Care site, we did a

Over on our Journal Watch AIDS Clinical Care site, we did a