An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

March 13th, 2024

CROI 2024 Denver: Really Rapid Review

One of the most rewarding things about social media in medicine is tapping into the minds of other smart people in your field, especially people you can’t otherwise interact with on a day-to-day basis. When that person is someone like Dr. Sébastien Poulin — a funny and indefatigable ID/HIV doctor from Montreal — it’s especially worthwhile.

One of the most rewarding things about social media in medicine is tapping into the minds of other smart people in your field, especially people you can’t otherwise interact with on a day-to-day basis. When that person is someone like Dr. Sébastien Poulin — a funny and indefatigable ID/HIV doctor from Montreal — it’s especially worthwhile.

Over the past few years, he’s taken the time to scan the entire program of an upcoming ID/HIV conference, selecting his highlights. With the caveat that no one’s highlights will be exactly like anyone else’s, these reviews have nonetheless provided a framework for going to an upcoming meeting that I’ve learned from, valued, and greatly enjoyed.

Well, this year Dr. Poulin could not make the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2024, which took place in Denver last week. So with a nod to him — get well soon! — here’s a Really Rapid Review™ of some of the studies from this year’s meeting that I found particularly interesting.

It’s the first time CROI has been in Denver since 2006 and, while no one presented a viable strategy for HIV cure or an effective HIV vaccine, we saw plenty of interesting studies. Here’s a sampling, roughly ordered by treatment, complications, and prevention.

After virologic suppression, long-acting injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine (CAB-RPV) was superior to oral antiretroviral therapy (ART) in those who struggle with ART adherence. So many good things to say about this study — it was randomized, it used economic incentives successfully, it included a population rarely included in clinical trials. And here’s an irony: the net benefits of using CAB-RPV on a per-person basis are likely to be much greater in this study group than in those for whom the treatment is FDA approved, who are already doing well on oral ART. Think about that for a moment.

CAB-RPV injected every 2 months was noninferior to continued oral ART in Africa. Conducted in South Africa, Uganda, and Kenya, the study demonstrated that this treatment would be effective even with infrequent (every 24 months) viral load monitoring and, more remarkably, with a high proportion harboring non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI; 10%) and integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI; 8%) mutations on proviral genotypes done on baseline samples. (I still would not recommend this regimen for people with known resistance!) Two of 256 CAB-RPV recipients developed integrase resistance.

Once-weekly lenacapavir and islatravir maintained virologic suppression. The weekly dose of islatravir was 2 mg and did not lower total lymphocyte or CD4 cell counts. This is the first once-weekly oral ART regimen with demonstrated efficacy, with phase 3 studies planned.

Other once-weekly oral agents are in development. These include an integrase inhibitor, an NNRTI, and a nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor (NRTTI).

In a study conducted in Haiti, switching people on a second-line boosted protease inhibitor (PI)-containing regimen to BIC/FTC/TAF was highly effective. Such individuals are known to have high rates of nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) resistance, so this reinforces the results of the 2SD study, which showed the safety of the boosted PI to second-generation integrase switch in maintaining virologic suppression — even without knowledge of this resistance. Proviral DNA resistance testing is planned. Remarkable that the primary investigators on site in Haiti could conduct this study in a setting with such extreme civil unrest, a heroic task. (Disclosure: I am a co-investigator.)

In an open-label, phase 2 study, daily oral bictegravir plus lenacapavir was compared to a continued complex regimen, with comparable rates of virologic efficacy. While they were given separately in this phase 2 study, a co-formulation of BIC/LEN is currently in phase 3 trials.

Twice-daily BIC/FTC/TAF achieved comparable virologic suppression to TDF/3TC plus DTG twice daily in HIV-related tuberculosis. Impressively, virologic suppression was observed in 97% of participants in both arms. After the presentation, some raised concerns about the unnecessary doubling of the TAF/FTC dose in the BIC/FTC/TAF group, but these agents are very unlikely to cause toxicity even with this increased exposure — and none was observed.

In a large (N=1362) observational study, the effectiveness of CAB-RPV in clinical practice was similar to clinical trials. Confirmed virologic failure occurred in 2% of individuals; a second study (N=278) reported an incidence of 0.9%. In one single-site report, 4% (3 out 75 patients) experienced this negative outcome and are now on PI-based regimens, with a suggestion that irregular injection practices at an independent infusion center may have contributed. Treatment failure with resistance is the most dreaded outcome of this CAB-RPV regimen, so it’s good to have these “real world”* data.

(*Ouch. Some people hate that term. I find it mildly annoying, preferring “in clinical practice”, which my friend Dr. Eric Daar hates. Oh well. But “real world” is so widely used these days it’s hard to avoid — so I succumbed and used it.)

A case series demonstrated the effectiveness of combining long-acting cabotegravir plus lenacapavir. The most commonly cited reason for using cabotegravir without rilpivirine was baseline RPV resistance — which is especially likely in people with long-term HIV and prior treatment failure, and is a major issue globally. From a practical standpoint, cabotegravir alone (without RPV) for HIV treatment is not FDA approved — only for prevention — which means that clinicians must discard the RPV when obtaining it for treatment and used in this fashion.

Ward 86 in San Francisco again reported high rates of viral suppression for people with viremia who were treated with CAB-RPV. Out of 59 such patients followed to week 48, 81% (48/59) remained on LA-CAB/RPV and were virally suppressed; an additional 7 patients were on alternative ART and suppressed. Only 3 of 59 (3%) experienced virologic failure with resistance. These are some of the core data that motivated the change to the IAS-USA treatment guidelines, discussed here previously.

Several studies (abstracts #117-121) with broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) demonstrated that we’re still far from seeing these agents as part of viable ART strategies. Issues remain the complex, slow, and expensive test for resistance; a high proportion of people with pre-existing resistance once the test is done; intravenous administration (for some bNAbs); and, even if levels achieved are adequate with a susceptible virus, still a higher rate of failure than we see with standard ART. On the flip side, bNAbs may offer the first chance at twice-yearly therapy (with lenacapavir); updated results from that study were presented in a small number of patients.

Two years after a programmatic switch to tenofovir/3TC/dolutegravir (TLD), virologic failure with DTG resistance was observed, but uncommon. Not surprisingly, it was more likely in those who were viremic at switch — individuals who not only struggle with adherence but also are more likely to harbor NRTI resistance mutations.

A separate prospective cohort study showed that people with treatment failure after switching to TLD had low tenofovir diphosphate levels. Levels were particularly low in those with failure on boosted PI regimens prior to the TLD switch, confirming that suboptimal adherence continued to be a problem for people on failing therapy.

Detection of resistance mutations by proviral (“archive”) genotypes over time is highly variable. It’s not that the mutations come and go — it’s that the sampling process may or may not detect them. The take-home message is that this test has a strong predictive value positive for detected mutations, but negatives should be viewed with appropriate caution.

How effective was lenacapavir in patients with no other fully active drugs? In this analysis from the CAPELLA study of highly treatment-experienced patients, 12 participants had zero fully active background agents when treated with lenacapavir. Regardless, 8 of 12 still achieved and maintained virologic suppression. While such a strategy isn’t recommended (always best to use active drugs in combination), it may be necessary in certain individuals under extreme resistance situations. Results remind me of ACTG 364*, when two NRTIs plus efavirenz — another potent but relatively low-resistance barrier drug — still suppressed viremia in 62% despite extensive baseline NRTI resistance.

(*How’s that for a blast from the past?)

In a randomized clinical trial of hepatitis B non-responders, the HepB-CpG vaccine (HEPLISAV-B) was superior to the standard recombinant vaccine in inducing a seroprotective response. Both two and three doses of the vaccine achieved this favorable result. This is the kind of study that should lead to a change in vaccine guidelines.

In patients with positive hepatitis B core antibodies, switching to a two-drug antiretroviral regimen without tenofovir was not associated with transaminase elevation. This applied even to the 118 individuals not on 3TC or FTC; the study mixed those with and without HBSAb. A second study, by contrast, demonstrated hepatitis B reactivation in 1 of 7 patients with isolated anti-core antibody (no surface antibody) when switched to a non-tenofovir and non-3TC/FTC regimen. A take-home message from the various studies to date? Those with isolated anti-HB core antibodies should, if possible, remain on anti-hepatitis B-containing ART; switches to regimens without tenofovir or FTC/3TC should be monitored for hepatitis B reactivation.

Simultaneous initiation of HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment was highly effective. The regimens used were BIC/FTC/TAF and SOF/VEL for HIV and HCV, respectively. Out of 128 patients enrolled (52 HIV treatment-naive), all achieved HIV viral suppression, and 98.4% (126/128) had HCV cure by sustained virological response (SVR) 24 assessment. Imagine trying to do something like this in the early ART and interferon for HCV eras — it is extraordinary how far we have come with HIV and HCV treatment!

The final results of the DOXYVAC study were presented — and the meningitis B vaccine just missed demonstrating significant protection against gonorrhea. This randomized trial looked at both doxy PEP and the meningitis B vaccine in a factorial design, and we learned at last year’s CROI that doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis (doxy-PEP) intervention was protective. These updated results showed the incidence of gonorrhea in the vaccine arm was numerically lower than no vaccine (58.3 vs 77.1/100 person-years, respectively), for a hazard ratio of 0.78 (95% CI 0.6-1.01)*. When a result is this close, the most conservative conclusion is that “a small benefit cannot be excluded.” Even if that benefit is real, a better gonorrhea vaccine would be of great use!

(*Time to quote Maxwell Smart.)

In San Francisco, a policy of recommending doxy-PEP to men who have sex with men (MSM) and trans women was strongly associated with a decline in the incidence of chlamydia and syphilis. No significant change was observed for gonorrhea. Additional supportive data on doxy-PEP came from a single clinic site and from the open-label extension of the DOXYPEP study. National guidelines are expected soon; they’re already in draft form.

In a VA-based study, prostate cancer was diagnosed at a later stage in men with HIV versus HIV-negative controls. This finding is of particular interest since prostate cancer has been historically one of the few cancers not observed to have a higher incidence in persons with HIV (PWH), strongly suggesting this result represents a screening gap — which, though controversial as a general tool, is still recommended in higher risk men.

Using data from the REPRIEVE trial, investigators reported that risk-prediction tools underestimated cardiovascular event risk in high-income regions only. The effect was particularly strong in women, who experienced about two and a half times more events than predicted; for Black participants 50% more.

In a prospective single-arm clinical study, semaglutide reduced the amount of liver fat by 31% at week 24. Not surprisingly, weight and glucose control also improved. A second analysis from this study demonstrated a reduction in psoas muscle volume, without impairing physical function. These are two of four studies on glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists at CROI, and my overall sense is that they’re working the same as in people without HIV — with the caveat that “Ozempic face” might be particularly distressing to people who have baseline lipoatrophy. The slide session started with a terrific review by Dr. Todd Brown.

Switching to a doravirine-containing regimen was associated with weight loss. Although it’s not specifically spelled out in the poster, the bulk of this effect most likely arose from switching the whole regimen to TDF/3TC/DOR, as TDF-based regimens are known to have weight-suppressive effects. Since in a previous clinical trial, there was no change in weight in a previously presented randomized trial of switching from BIC/FTC/TAF to DOR/ISL, it seems unlikely that switching just an INSTI to DOR would lead to weight loss — a question that will be answered by an ongoing clinical trial.

Damage to intestinal enterocytes might explain the weight loss and lipid-lowering effects of tenofovir DF. Twelve men on TDF and twelve on TAF underwent gastroscopy, with biopsies from the proximal and distal duodenum. Those on TDF had more histologic abnormalities (flatter villi and deeper crypts), as well as lower levels of certain nutrients absorbed from the proximal duodenum, and higher levels of serum intestinal fatty acid-binding protein, a marker of enterocyte damage. Both groups had evidence of mitochondrial damage on electron microscopy.

Women who switched to an integrase-based regimen during menopause experienced early accelerated increases in waist circumference and body-mass index. Comparison groups included women with HIV who did not switch regimens, and women without HIV — neither experienced these changes.

In rural Uganda and Kenya, a prevention “package” that offered the options of oral preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), PEP, and cabotegravir greatly increased the uptake of PrEP over standard of care. The effect was huge — a five-fold increase — and led to a significant reduction in HIV transmissions in those offered the package versus usual care.

In a prospective study of PEP, BIC/FTC/TAF was well tolerated with no seroconversions. Study results support previously published data. Given the low incidence of seroconversion in PEP users, we will never have a comparative clinical trial of different ART strategies that demonstrates one approach is better than another; as such, BIC/FTC/TAF seems like an optimal default choice since it’s simple, well tolerated, and has few drug interactions. Time to include this in PEP guidelines, which are in need of updating?

Three of six children with in utero HIV transmission stopped treatment without viral rebound. All mothers received ART during pregnancy, and the babies started treatment within 2 days of birth. Treatment was stopped at a median of 5 years of age, and the duration of remission was reported as 48, 52, and 64 weeks. Among the 3 children who rebounded, one did not do so until week 80 — hence it’s premature to call these kids cured.

So that’s a wrap! Of course it’s hardly comprehensive, so if I left out your favorite study or studies, have at it in the comments.

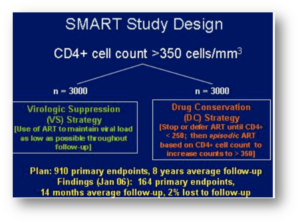

Here’s a reminder of the big news out of the first Denver CROI in 2006:

That’s the SMART study of CD4-guided treatment interuption which highlighted the oral presentations. I distinctly remember Dr. Steven Deeks telling me in the hotel lobby, “You’re not surprised at that result, are you? Of course stopping treatment is a bad idea.” As usual, Steve had figured things out long before any of us!

That meeting also featured a trio of drugs destined to change the history of HIV treatment for people with resistant virus — darunavir (TMC-114), etravirine (TMC-125), and raltegravir (MK-0518). In the years to come, many who had never previously achieved viral suppression reached “undetectable” for the first time, and remain so today.

March 2nd, 2024

Just as CROI Gets Ready to Start, an Important Change to the IAS-USA HIV Treatment Guidelines

One of the top experiences of my ID career has been working with a research group that does HIV disease modeling. The people involved are without exception smart, collaborative, generous, funny, and hard-working — an amazing combination of positive traits.

One of the top experiences of my ID career has been working with a research group that does HIV disease modeling. The people involved are without exception smart, collaborative, generous, funny, and hard-working — an amazing combination of positive traits.

They get this, I believe, from their leader and founder, Dr. Ken Freedberg, who sets a great example. He has been a research mentor and friend of mine for years.

(You might recognize one of his many mentees: Hi, Rochelle Walensky, if you’re reading this!)

Anyway, it’s not often that I disagree with Ken on anything in the HIV treatment area, so it’s been an interesting couple of years as we discussed a strategy that’s been on the cutting edge as a way to manage some of our most challenging cases — namely, the people with HIV who (for a variety of reasons) do not take oral antiretroviral therapy.

As anyone who does HIV care knows, this small fraction of our patient population occupy a disproportionate share of our worries, account for the bulk of hospitalizations and HIV-related deaths, and as a result represent an ironic (and tragic) contrast to the extraordinary success of HIV treatment. It’s unfathomably frustrating on many levels.

The reasons they do not take ART are numerous, and not mutually exclusive — including denial, stigma, mental illness, and substance use disorder — but a glimmer of hope emerged with successful reports of the off-label use of injectable cabotegravir-rilpivirine (CAB-RPV) in a group of people with ongoing viremia who are not taking ART. While these reports first appeared from Ward 86 in San Francisco under the direction of Dr. Monica Gandhi, other studies and anecdotal evidence from clinical treatment sites (including our own) followed.

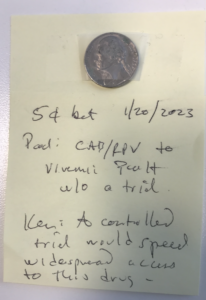

But back when these reports first emerged, Ken took the position that widespread use of this treatment would require a prospective clinical trial, preferably with a randomization to standard of care, to prove that it works; he furthermore thought that it would not appear in guidelines until such a study took place. I countered that such patients have already proven that they will experience treatment failure if randomized to continue oral therapy, and that such a study would not be necessary to show that injectable ART is the best strategy under these desperate situations.

We bet a nickel. Evidence in photo at the top of this post.

Ken may have gotten his wish. The injectable strategy for people who struggle with adherence got a boost with the announcement of results from the LATITUDE trial, an ACTG study that enrolled people with treatment failure. It provided economic incentives to lower the viral load to undetectable with oral ART, and then randomized them to injectable versus continued oral therapy. The study was stopped early in favor of the injectable ART arm; we’ll see the full results at CROI next week as a late-breaker.

It’s not quite the same population as the one we’ve been discussing (the randomized switch to CAB-RPV in LATITUDE is only after virologic suppression), but it’s close.

Meanwhile, I’ve been energetically pitching to my colleagues on the IAS-USA Guidelines Panel to update our recommendations for use of cabotegravir-rilpivirine for people not able to take oral ART who have advanced HIV disease. The argument is simple: such an intervention can be literally life-saving given the poor prognosis of untreated HIV with low CD4 cell counts, or prior HIV-related complications. Takes us back to the bad old days, pre-1996.

I’m thrilled to report that this revision just appeared in JAMA. Note that this intervention is not for all people who struggle with adherence — just those at the highest risk for HIV disease progression:

When supported by intensive follow-up and case management services, injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine (CAB- RPV) may be considered for people with viremia who meet the criteria below when no other treatment options are effective due to a patient’s persistent inability to take oral ART:

– Unable to take oral ART consistently despite extensive efforts and clinical support

– High risk of HIV disease progression (CD4 cell count <200/μL or history of AIDS-defining complications)

– Virus susceptible to both CAB and RPV

It will be critical to assess how this treatment does in clinical practice, to monitor for emergent integrase and NNRTI resistance, and to provide the intensive case management services this patient population deserves. And if a prospective study starts employing this strategy, one that does not involve a randomization to continued oral ART, all the better to gather more data on how it performs. Enrollment highly encouraged.

But as we’ve demonstrated in a modeling study, injectable CAB-RPV doesn’t need to be 100% effective in a population with advanced HIV disease to save lives — even a virologic suppression rate of 45% would do the trick.

Did I win the bet? Or did Ken? I say we both save our nickels, and call it a tie.

February 20th, 2024

Variability in Consult Volume Is a Major Contributor to Trainee Stress — What’s the Solution?

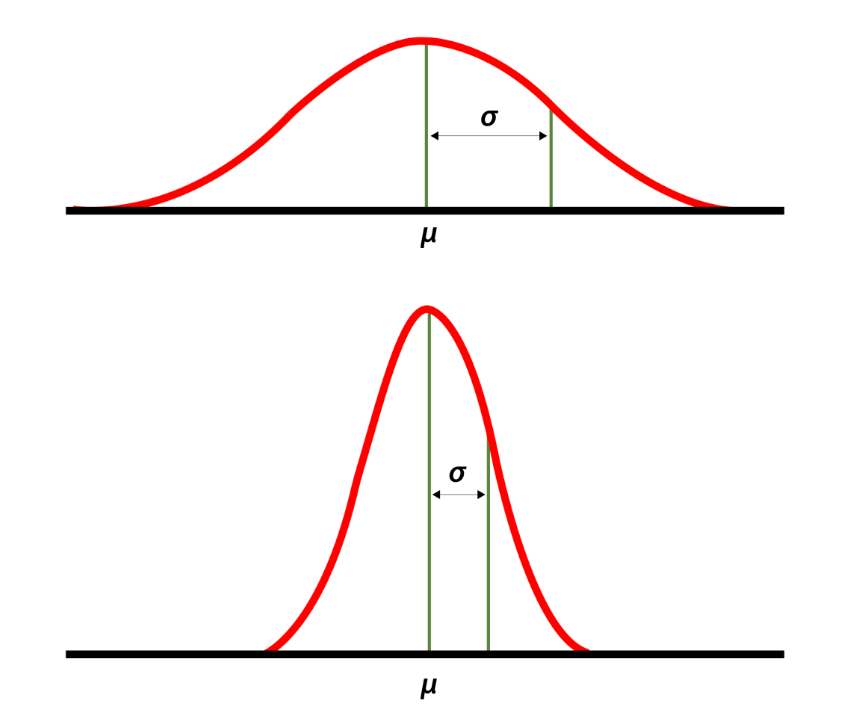

High and low standard deviations around the mean. Source: National Library of Medicine.

Back when he was program director of our ID fellowship, Dr. David Hooper would give the applicants a description of our program. One of the key parts was his estimating the workload — in particular, the number of new consults per day.

“We average three to four consults a day,” he said. “But there’s a high standard deviation around the mean.”

That last part he said humorously, with a smile and a shrug. It was a wonky joke, but everyone got it since it’s well known that consult volume is unpredictable — nothing different about our program compared to any other. But this variance is a critically important part of consultative medicine, one I’d argue is one of the key drivers of physician stress, especially for trainees.

What do I mean? Join me in this thought exercise. You’re an ID fellow with a weekend off, and it’s Sunday night. You’ll be picking up a new service on Monday — first day of a new rotation! — and will be responsible for learning the details of the cases on your team and catching up on weekend events.

Not only that, you’ll also be seeing the new consults that get called in that day. You know Monday will be busy, but how busy?

Let’s take two scenarios for the number of new consults — which would you choose if given the option?

- A day when you will get four new consults — no more, no less. Once you’ve done the fourth, you’re done with new consults for the day.

- A day where your consult volume that day is uncertain. You know that the average number of consults/day in your program is between three and four; however, light days (one or two consults) are balanced out with very busy days of five, six or, rarely, even seven new consults.

I suspect most of us would choose the first option, even though the “average” outcome of choice #2 is fewer consults.

This says a lot about psychology, risk perception, and our decision-making strategies. In studies of decision science, participants often choose the “sure thing” over a potentially more valuable but uncertain outcome — a phenomenon often referred to as “loss aversion.”

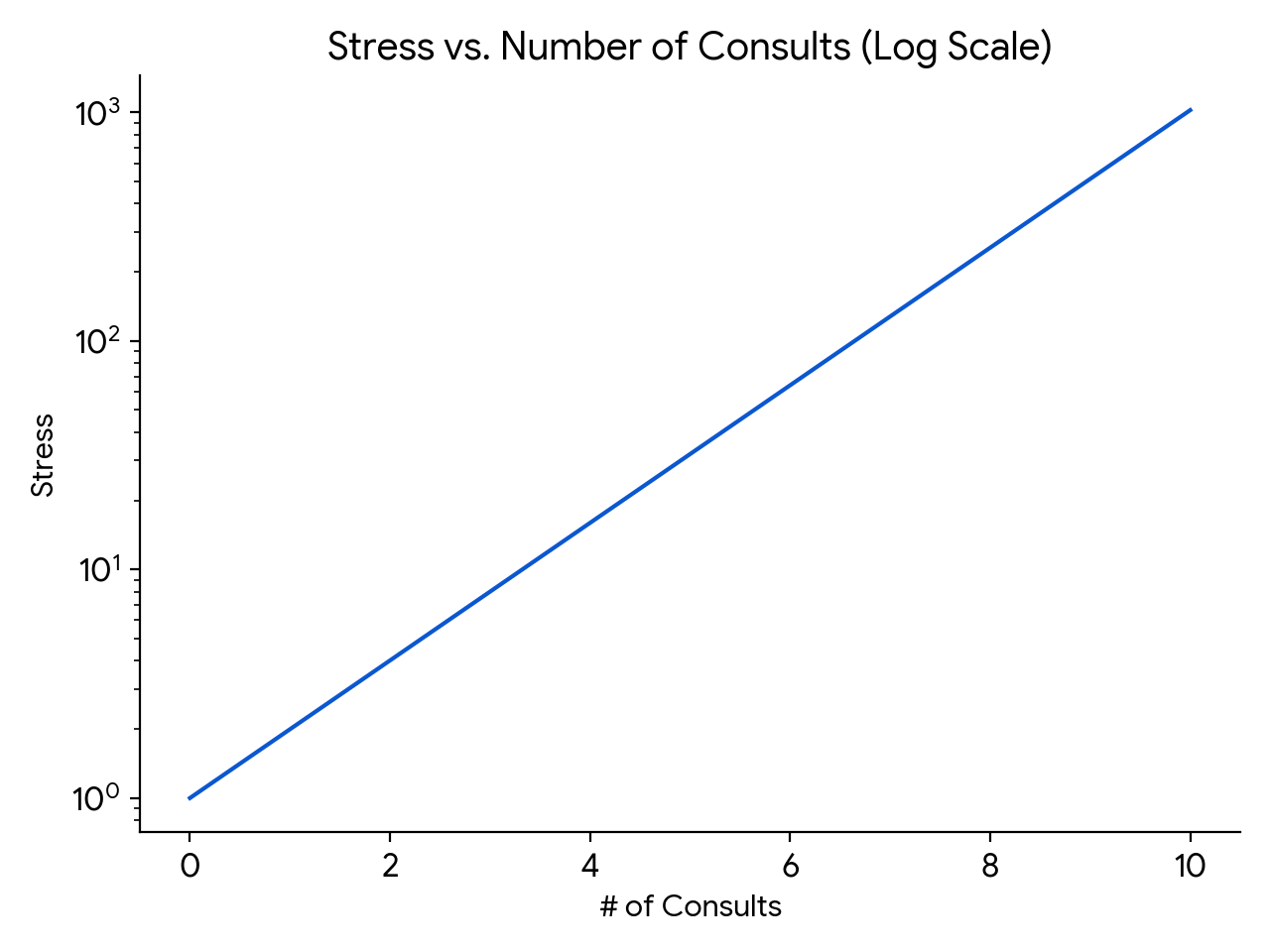

An important point is that the relationship between consult volume and stress does not increase linearly — it’s more like on a log scale, which means that going from five to six consults is much more difficult than going from three to four, even though both just add a single new case. And what this additionally means is that getting six consults is much more than twice as stressful as getting three.

(How about those math skills. Impressive, eh?)

Finally, there is something inherently stressful about living through the amorphous blob of work potentially coming your way in choice #2. The day could start out relatively peacefully, with just a single consult, making you cautiously optimistic but still vulnerable. But then, an hour or so after lunch, the chief resident in orthopedics could page you and say they’ve just accepted in transfer two patients with infected prosthetic joints — both of whom will need your attention when they arrive (whenever that will be).

That hypothetical day still didn’t yield more consults than in choice #1, but the unpredictability of the way they came in made the day seem so much more tense.

(Note: This discussion must seem foreign to ID doctors in private practice, where consult volume directly links to personal revenue. But try to imagine yourself back in the days of your ID fellowship, however, and you’ll get what I mean!)

I thought of this challenge recently since we recently had quite the week when it comes to consult-volume variance. Afterwards, I sent a note commenting about this to Dr. Daniel Solomon, our fellowship’s current Associate Program director. His response:

I think the hardest thing about being on service (and in particular first-year fellowship when they are on the front lines holding the pager) is not the cumulative volume of work. It’s the unpredictability of each day. It is hard to make reliable plans with friends and family when the variance is so high.

I couldn’t agree more.

Solutions? One thing we proposed was to unload some of the simpler cases to an eConsult system, where inpatient medical and surgical teams received clinician-to-clinician advice from us after a discussion, record review, and our writing a brief note in the chart. The issue? As I wrote previously — no one has figured out how to pay for these things. Proposal rejected.

Some say that instituting a “cap” on new consults solves this variance-in-volume problem, and there’s definitely some truth to that. Such caps limit the burden of a high consult day on the ID fellows, much as a cap on admissions does the same for interns and residents. Plus, that uncertainty factor is greatly reduced.

This solution isn’t straightforward to implement, however. First, who sets the right number? ID training programs have a wide range of expected new cases per ID fellow per day. I’m very much aware that our daily average of three to four per day isn’t the same as other programs, some of which have considerably higher volume.

Also, should the cap be the same regardless of the number of patients you’re already following, or the complexity of the service? Should it be the same for general ID consults as it is for transplant and oncology services, which have an average complexity per case that’s much higher? And how do we account for variable team structures? Some regularly have rotating medical residents and/or students on board to help defray some of the work, while others rarely have these learners.

One other issue with a cap relates to the inherent value of clinical volume for volume’s sake. There’s a cliché in clinical medicine that goes, “The more you see, the more you see.” Since many ID programs (ours, for example) have only 1 year of intense inpatient clinical training, why not make the most of it, provided the volume isn’t too brutal? We all know that there’s no better way to learn about a clinical entity than to care for a patient who has it — the first-year ID fellow who sees CNS nocardiosis, or falciparum malaria during pregnancy, or disseminated histoplasmosis will never to forget those distinctive but relatively rare diseases, to choose just three that recently popped up on our inpatient service.

Although it doesn’t seem so at the time — an understatement — even doing a consult on “routine” cases brings value. Seeing many examples of Staph aureus bacteremia, or infected abdominal collections, or osteomyelitis under sacral pressure ulcers cumulatively helps develop an approach to these common entities, and to appreciate the wide variability in clinical presentation and management.

So far this discussion about the cap looks at it from the fellow perspective. It doesn’t address the fundamental cause, which is that the consulting services need our help caring for their patients, and it’s our mission to help them. That the volume of these requests is unpredictable isn’t their fault. Hence, once a trainee is capped, this work then must get done by someone else, right? Is it the on-service attending, who is still responsible for staffing the fellow-seen cases on this already busy day? Some other faculty member waiting in the wings, eager to do a late afternoon bunch of consults? Who has those faculty?

In summary, there are pros and cons to putting a cap on new consults for ID fellows. I’d be interested to hear — do you have a cap on new consults in your fellowship program? If so, what is it, and how did you decide on a number? Who’s responsible for doing the work over the cap? Share your thoughts in the comments section.

And enjoy this quite remarkable video, which somehow escaped my notice when it first appeared. Glad they remembered to press the record button!

January 25th, 2024

Printed Medical Textbooks — Going, Going, but Not Quite Gone

Take a look at the things behind my desk at work:

- cute photos of family and dog

- a bunch of sentimental objects, gifts from grateful patients or colleagues

- a smattering of miscellaneous plaques and clocks

- pictures of our current (awesome) first-year ID fellows and other stuff

- a bunch of books, several of them many inches thick

You may not be familiar with item #5 on this list — those hefty books — so allow me to remind you what they are. Those are medical textbooks. Because if you’re like me, there’s a decent chance you haven’t opened a medical textbook in months, or even years. It’s these that we’ll be chatting about today.

There was a time when consulting these heavy tomes fortified our approach to clinical care on a regular basis. Now, many of us barely ever open them; instead, we look online to recently published papers, comprehensive reviews, the latest treatment guidelines, or other sources to stay up-to-date.

(See what I linked there? Full disclosure, I’ve been a contributor to UpToDate since its very early days, as I’ve detailed previously.)

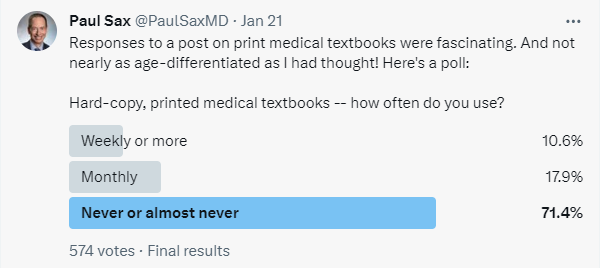

For evidence supporting this move toward online sources and away from print textbooks, take a look at the results of this poll:

Granted, those who respond to polls on Twixter already live much of their lives online, and hence least likely to turn to an actual printed book. That’s why I repeated it below — different audience, maybe a different response. But still, if you’re a doctor, nurse, pharmacist, or student, chances are excellent you own one or more textbooks, but they’re sitting somewhere in your office, their hundreds (or even thousands) of pages as fresh as the day they left the publisher.

Here are some representative comments I received related to this post:

I literally never use paper textbooks for anything and haven’t for about a decade.

I’m 35 and have a deep nostalgia for physical print books, so I have all my old textbooks (including Harrison’s), but I never use them.

Textbooks in print? Never. Last time over 15 years ago. I do read from the textbooks online.

Have these books in my office shelf for the sentimental value. I have used them twice in last few years.

Wrote a chapter in a textbook. Received free copy. Can’t find a med student around here who will take it off my hands.

Several of these textbooks might include outdated information, pointing to a critical problem with printed books highlighted by Dr. Michael Calderwood:

They look pretty on a shelf but are already outdated by the time that they arrive. Knowledge is changing quickly, and we need readily accessible, expert curated, living documents.

Even worse, how many of us replace the old versions? Guilty as charged — I checked the publication dates on some of the textbooks displayed on my shelf. One is from 2003! Another, 1997! No doubt there are some clinical pearls in these old books, but my advanced math skills calculate that they are decades outdated. Reader beware!

Or maybe your textbook serves another function:

In our fellows’ room, we have an old version of Mandell holding up a computer monitor (which occasionally displays the electronic pdf from the new version). That’s how we use it.

Importantly, there was a vocal contrasting opinion, no doubt representing the 10-28% from the poll. And it’s so interesting that it’s not just older doctors who have this favorable view of printed textbooks! Dr. Courtney Harris, a recent graduate from our ID fellowship program, weighed in with this comment:

I love them. I probably pull one out once a month for hard clinical questions or when I just need a deep overview of something I feel like I really don’t have a good grasp on. Plus I love physical books in general – having a few in my office just gives me joy.

This minority but opinionated group must help sustain the traditional textbook market. Some who continue to use print textbooks say that they can’t learn things as deeply from online sources — a reminder that there’s no right way to learn, just that people take different paths to their own education.

But going back to the numbers from the poll, I maintain that print medical textbook users represent a small (and I suspect shrinking) group. I wonder how long this fragile relationship will continue, especially because writing, producing, and publishing these books isn’t cheap — and neither is their price tag should you want to purchase one.

I confess that exploring this topic fills me with a tinge of nostalgia, one almost reaching melancholy. It has a similar emotional effect to hearing the accounts of other print media dropping in popularity and becoming decreasingly viable economically. Newspapers and magazines (in particular) have been decimated.

Augmenting the sadness is my longstanding participation in writing for some of these texts. For generations of doctors, an invitation to contribute to these pivotal books signaled a true honor. You felt a deep responsibility to research and know the topic thoroughly, to get it just right. After all, someone reading it could make treatment decisions based on your summary of the existing literature. Authorship in these well-known reference books acted as a good way for academic physicians to plant a flag that reads, “I belong.”

Today? A colleague of mine recently submitted a revised version of a chapter to one of these pivotal texts, one that I co-author with him. As it was being revised, I seriously wondered who would ever read it. I can’t imagine the numbers would come anywhere close to a comparable topic in UpToDate, or as covered in a treatment guidelines paper.

I wouldn’t give up on the printed stuff completely, though. Not only are there still people like Dr. Courtney Harris who still value the concrete, real thing you can hold in your hand, but perhaps there’s a burgeoning market: my 20-something-year-old daughter told me recently how much she loved subscribing to the print versions of two high-quality magazines.

They arrive in her mailbox each week — her actual mailbox, not the electronic one. Imagine that.

January 2nd, 2024

Reflections on Working in the Hospital During the Holidays

On-service ID team, December 25, 2023

For the zillionth year in a row, I spent the Christmas holiday working in the hospital. For me, it’s not much of a sacrifice — we don’t celebrate Christmas, and my kids are long out of school so the strict limits on when we can take vacation are a thing of the past. But it puts me in a notable minority, as around 90% of U.S. workers have the day off.

So what do we 10%-ers get in exchange for working? Here’s a secret — we get plenty. A brief rundown:

Camaraderie. This is one of the best things — the immediate recognition among those in the hospital that we’re in this together. Take a look at that picture of the faculty and fellows on call. Do those look like unhappy doctors? Importantly, a couple of the members of this quintet do celebrate Christmas, yet made the sacrifice to come in. To them, an especially big thank you!

Continuity. Sadly, illness doesn’t take a holiday and neither do hospitals — they’re a 24/7 business. The patients who must be in the hospital over Christmas are mostly quite sick, or socially disadvantaged, or both. They’re usually pretty upset about having to be there, quite understandably. So they very much appreciate that some of the doctors who were following them before the holidays know them during the holidays too.

Barter. Working Christmas allows us to trade this important holiday for others. For example, I haven’t worked Thanksgiving in years and almost always find a way to get coverage for Passover. Already I’ve blocked off Christmas 2024 as a time both my wife and I will be working — you’re welcome, happy to do it.

Bonus. Several years ago, our division adopted the policy of providing a small bonus to the on-service faculty for working certain important holidays. (Apologies to our residents and fellows who don’t get this. Maybe that will change now that they have adopted a union?) Note that for most salaried workers, it’s typically 1.5 or even 2 times the hourly rate. Believe me, it’s appreciated.

Golden Citizenship Award

Citizenship. Some of the crew on call over Christmas volunteer to do so nearly every year. As the person in charge of clinical scheduling, I hereby give them the Golden Citizenship Award. Mike, Eric, Amy, Anna — you know who you are — thank you! Place this award in a prominent place, it’s quite valuable.

Sustenance. The hospital president every year sends around an email wishing us happy holidays and announcing that lunch and dinner in the hospital cafeteria are free. This year’s entrees were pretty good, both the chicken and vegetarian options, though I wasn’t a big fan of the dessert. But if it’s sweets you’re after, no worries — hospitals are replete with goodies, homemade and otherwise, practically everywhere you go. This year, I arrived on one hospital unit to find gorgeous homemade chocolate chip cookies invitingly set out on a tray with a sign saying, “Take One”; another unit had a huge basket of assorted Lindt truffles. Noticing my rapt attention to the chocolates, a kind nurse insisted I not leave the floor until taking a few. Yum.

Appreciation. If you work over the holidays, you can pretty much guarantee that plenty of people will thank you. Patients, doctors, nurses. Hey, note that even I am thanking people (see “Camaraderie” and “Citizenship”, above).

Learning. Medicine is a lifetime of education! No reason this needs to stop over the holidays, right? Cryptosporidiosis, vascular graft infections, bacteremia as a complication of appendicitis, drug-induced vasculitis — summarized these topics and others in an on-line thread. Plus, one of the fellows shared an interesting paper on antibiotic-associated neutropenia. Much appreciated, Carlos!

Pace. Hospital census used to drop dramatically in the week before and after Christmas, leading to a delightfully slower pace in what is usually a very busy environment. While that effect is much less dramatic with the post-pandemic bed crunch, there are still fewer elective surgeries and admissions. So it’s still not quite as busy as during the rest of the year, a welcome break. And if you’re worried that I’m going to jinx this effect by even mentioning it, I refer you to a classic paper.

Diversity. Here’s a wonderful thing that made me smile on December 25, courtesy of Dr. Vamsi Aribindi:

Happy New Year, everyone!

December 22nd, 2023

A Holiday Season 2023 ID Link-o-Rama

Hey Image Creator, make a holiday greeting card in mid-century modern with dogs.

A bunch of ID (and a few non-ID) items of note as you prepare for the peak of the holiday season.

The President of IDSA has written an open letter to the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) asking for changes to the recertification process. Current IDSA President Dr. Steven Schmitt proposes several modifications, all designed to reduce the burden and cost to the doctors. It importantly includes results from a member survey that shows a majority of ID docs believe the program “adds no clinical value, does not positively impact clinical practice and contributes to burnout.” A whopping 92% of early career ID doctors find the cost a burden. Note that it’s hard to find any survey that has responses so overwhelmingly negative about an ostensibly educational program.

Here’s part two of my commentary on this ABIM issue. In this update, the current president of ABIM gets mad, says something he later regrets (maybe), apologizes (accepted, thank you!), but sticks to his guns anyway. After reading this, my ID colleague/pal John Badley kindly sent me an email stating, “Paul, you and your blog are not despicable.” Thanks for the reassurance, John! And let me be clear once again — I do believe that it’s essential physicians continue to learn, and to keep their clinical practice updated, but I’m increasingly aware that the recertification process as currently designed has major limitations.

Patients who had recently used PrEP and acquired HIV were 7 times more likely to have baseline resistance at HIV diagnosis than those who never used it. The most likely explanation for this excess resistance is that PrEP was stopped, and then re-started after HIV was acquired. The most common mutation detected was M184V (lamivudine and emtricitabine resistance), so DTG and BIC-based three-drug therapy still should be active. Rather than use these data to discourage use of PrEP, we should leverage it to encourage better adherence and more regular follow-up.

Two investigational antivirals hastened time to recovery in people with COVID-19 compared to placebo. VV116 is a remdesivir oral analogue, and leritrelvir is a SARS-CoV-2 protease inhibitor given without ritonavir. Neither study reported significant safety concerns, and both would have fewer drug interactions than nirmatrelvir/r (Paxlovid), especially VV116. While the authors didn’t comment on rebound, recall that this issue does not happen with IV remdesivir. These two drugs (VV116 in particular) along with ensitrelvir all appear to have major advantages over our existing options for outpatients. As cases rise again this December (as they have every December since 2020), I eagerly — and confess impatiently — await better alternatives!

For children presenting to emergency departments with acute gastroenteritis, molecular testing led to a significant increase in identification of a potential pathogen and decreased the need for follow-up visits. The diagnostic yield increased from 3% in the pre-intervention period compared to a whopping 74% with molecular testing. Molecular testing was associated with a 21% reduction in the odds of any return visit, a clinical benefit strongly endorsed by my pediatrician wife (fewer “he had another loose poop” calls). These results remind me of one of the early studies of enterovirus PCR for meningitis, showing that even when you don’t have a treatment, sometimes just knowing the diagnosis can have benefits.

Treatment of men with UTIs and fever is one of the exceptions to the “shorter is better” rule of antibiotic courses. More relapses and treatment failures occurred after the 7 vs. 14 day course; strongly suspect prostate infection is the nidus for recurrence. I’d add high-risk vertebral osteomyelitis to this short list of conditions that may require longer treatment, based on both a prior observational study and anecdotal experience.

A microbiology laboratory tested 85 clinical isolates of beta streptococci for susceptibility to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, and doxycycline. The surprise (to some) winner? Trim-sulfa (100%), followed by clindamycin (85%), with every ID doc’s favorite doxycycline bringing up the rear, with only 57% susceptible. Some would argue that this in vitro activity of trim-sulfa vs. strep has long been proven in clinical studies of skin and soft tissue infections (such as one in kids and one in kids and adults), but that hasn’t stopped clinicians from frequently choosing double therapy with beta lactams plus trim sulfa for outpatient treatment of these infections. Guidelines, too, steer people away from trim sulfa for strep. Trim sulfa’s bad reputation vs. strep stems from an artifact introduced in a now outdated method of resistance testing, which had high thymidine content of the test media inhibiting the activity of the drug.

Weight gain after switching an NNRTI-based regimen to tenofovir DF/lamivudine/dolutegravir occurred only in those whose pre-switch NNRTI was efavirenz — not nevirapine. As previously observed, the women gained more weight than men. Also previously noted is that efavirenz has a weight-suppressive effect, which is not observed in other drugs in the NNRTI class — rilpivirine and doravirine also do not suppress weight. The mechanism by which efavirenz has this effect remains unclear, but I’m betting that this is an off-target toxicity. One confounder in this study is that most of the participants on NVP were on AZT/3TC, most on EFV were on TDF/3TC, and these NRTIs also influence weight.

In a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial, vitamin D did not lower the risk of upper respiratory tract infection in older adults. A large study, involving 16,000 participants, this is another negative vitamin D supplementation randomized trial we can add to a large pile. Oddly, in a prespecified analysis, the researchers observed a significantly lower occurrence of URI in the vitamin D group, compared to placebo, during summer only — exactly the opposite of what I’d expect. A protective effect also was seen in Black participants.

A synbiotic preparation called SIM01 improved certain symptoms of long COVID significantly more than placebo. These symptoms included fatigue, “general unwellness,” memory loss, gastrointestinal upset, and difficulty in concentration. There was a corresponding alteration in the treatment group’s gut microbiome. Confess I didn’t know what constituted “synbiotics” before this study — it means “a mixture of probiotics and prebiotics that beneficially affects the host by improving the survival and activity of beneficial microorganisms in the gut.” And in case you’re counting, this is the third COVID-19-related randomized clinical trial coming from China I’ve chosen to highlight.

A graphic designer provided a detailed account of her devastating symptoms from long COVID. This is a long, quite heartbreaking piece, beautifully depicted, painful to read. Clinicians will appreciate that for some patients, the meticulous record keeping provides some solace, the sheer volume of it starting in 2020 no doubt correlating with the severity of her symptoms. She writes, “I thought that if I collected enough data, I would eventually figure out what was going wrong. But no matter how much data I collected or how many correlations I tried to draw, answers eluded me. Still, I couldn’t stop tracking. My spreadsheet was the only thing I could control in a life I no longer recognized.”

A detailed pharmacokinetics study evaluated bictegravir/FTC/TAF in 29 virologically suppressed pregnant women with HIV. The main findings were that while concentrations of all three drugs during the second and third trimester were lower than postpartum levels (roughly 40-80% of postpartum levels, biggest reduction for bictegravir), the mean bictegravir exposures were still more than 6.5-fold greater than the protein-adjusted 95% effective concentration. No virologic failure or infant transmissions occurred. This regimen — the most commonly used in the U.S. right now — is still listed as having “insufficient data” in pregnancy guidelines. I wonder if this small study will change that category.

Latent infection with Toxoplasma gondii was associated with increased mortality. Note that I wrote “associated” and not “causes”, as this large observational study found marked demographic differences between those who were seropositive and seronegative. One also wonders why the tests were sent to begin with — certainly it’s not a commonly ordered test, done only in very specific clinical circumstances. Nonetheless, it’s worth remembering that even latent infections can have consequences, as is increasingly evident with studies on CMV.

A Mostly Non-ID Section:

The story behind the “booming business” of cutting under a baby’s tongue to improve breastfeeding. Although well intentioned, this procedure has minimal evidence to support its now growing use despite being widely recommended by certain lactation specialists. It also takes advantage of parents during a time of great emotional vulnerability when there is already enormous pressure to breastfeed. Here’s what we do know: it’s very profitable for the doctors and dentists doing the procedure, and it can have serious complications. I’ve been listening to wise pediatricians — especially one very close to me! — express concerns about this procedure for years, so it’s gratifying to see this exposed.

A survey of nearly 19,000 physicians found that nearly a third had a moderate or high “intention to leave” practice within 2 years. With the caveat that any survey may select only for those who are unhappy and want to express their discontent, the most striking figure from the paper places medical specialties in 4 different quadrants — along the vertical axis professional fulfillment, the horizontal proportion with burnout. Trust me, we don’t want to be in the bottom right (low professional fulfillment, high burnout). I was pleased to see that ID just escaped, sitting in the upper right — scoring higher than average on the burnout side of things (bad), but also higher on professional fulfillment (good)

A general internist wrote about the patients who fired him. In this excellent account of a difficult subject — and the valuable things he learned through the process — he tells the story of four such patients who left his practice. He concludes by writing: “To keep this reflection under 2000 words, I leave out the stories of two other patients. I am also not sure I could have tolerated writing more.” We need more of these stories in clinical medicine to balance out the “I came in and saved the day” anecdotes — which not surprisingly are much more common!

Hey, happy holidays everyone! Let’s wrap up the year with these American-born dancers living in Galway performing to a song written and performed by a singer-guitarist from Puerto Rico, who quite amazingly was born blind and started playing the guitar at age nine.

December 8th, 2023

Clinician-to-Clinician Advice Is Great for Everyone but Still Horribly Undervalued

One of the best things about being an ID doctor is that you get to interact with all the medical and surgical specialties. This is one of the most common answers to the question, “Why did you choose to specialize in ID?” and it certainly resonates with me.

One of the best things about being an ID doctor is that you get to interact with all the medical and surgical specialties. This is one of the most common answers to the question, “Why did you choose to specialize in ID?” and it certainly resonates with me.

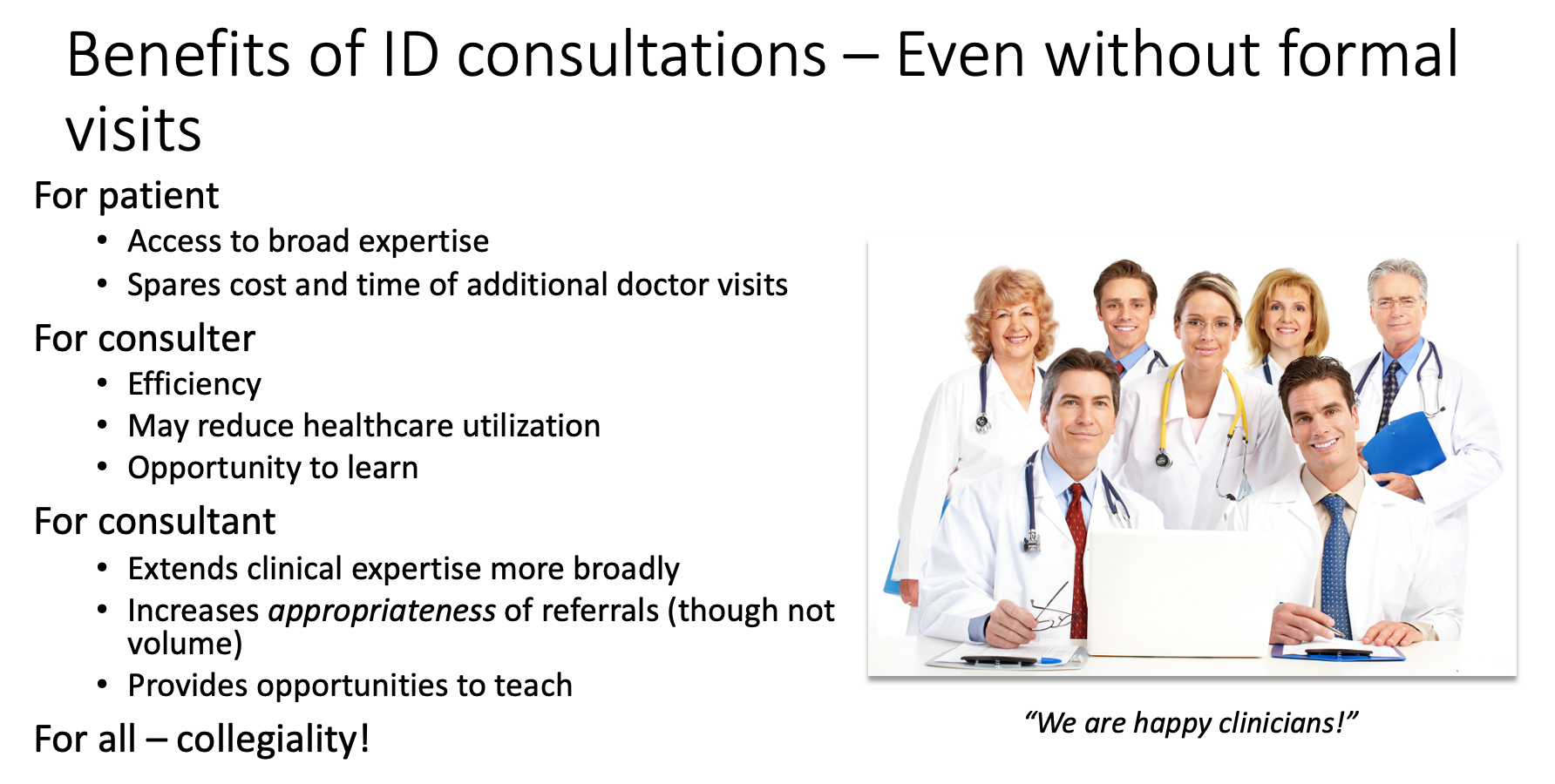

As a result, we’re frequently in the position of providing clinician-to-clinician advice — which, when done without seeing the patient, was historically called a “curbside” consult. Informally asked, often prefaced with “Can I ask you a quick question,?” these curbsides have pros and cons that I’ve written about on this site numerous times.

It’s a topic near and dear to my heart, so much so that I have an entire talk on this subject that starts with several slides outlining both the benefits and the risks of this practice. And for the hard-liners (see photo above on the right) who never do clinician-to-clinician advice without seeing the patient, trust me there are benefits, some of which I’ve summarized on this slide from my talk:

In a similar theme, around 10 years ago, our hospital system started offering “eConsults,” adapting similar programs from elsewhere. Instead of referring a patient for in-person consultation to a specialist, clinicians could place an order in the medical record, and a specialist would review the question, the data from the patient’s chart, and write a note.

This form of consultation occupies an intermediate place between actually seeing, interviewing, and examining a patient, and the informal “curbside” consults where you give just general advice, undocumented anywhere. Completing the note is expected within 24 hours. Because eConsults are asynchronous, meaning we specialists don’t need to respond immediately, they are far less disruptive than getting paged or called directly.

A huge advantage of this approach over curbsides is that we can review the primary data. In addition, the consulting clinician now has specific advice documented in the chart on how to proceed, which may include ordering additional tests or modifying treatment. In a small proportion of eConsults, we advise that the clinical scenario is too complex to resolve without a formal visit. After all, we can’t put a limit on the complexity of the case — that’s at the discretion of the consulting clinician. When that happens, fortunately, we’ve still been able to weigh in on tests to order ahead of time that will make an in-person visit with us or another specialist more valuable.

How has the program done?

To say eConsults have caught on vastly understates it — they are a huge hit. Imagine if a miraculous Beatles reunion became the opening act for Taylor Swift. To quote one primary care doctor who previously had a solo practice, “It’s by far the best thing about working here.”

You can easily see why they’re so popular. Not only do clinicians get access to nearly the full range of medical and surgical expertise at our academic medical center, often an eConsult can spare their patients the inconvenience and cost of an extra doctor visit. Indeed, published data on our program strongly show that eConsults decrease the volume of formal referrals, while increasing their appropriateness. Evaluations from different centers (here and here) had similar findings. Implied in these data is that care efficiency improves and the total cost to the healthcare system declines (fewer visits = lower costs).

Sounds like these eConsults are a real advance, for patients, clinicians, and payers, a rare win-win-win trifecta — so much so that we proposed expanding the eConsult service to inpatients to deal with the never-ending deluge of curbsides that arise in hospitalized patients.

So far, all sunshine and warm tropical breezes. So, what’s the problem?

No one has figured out how to pay for these things.

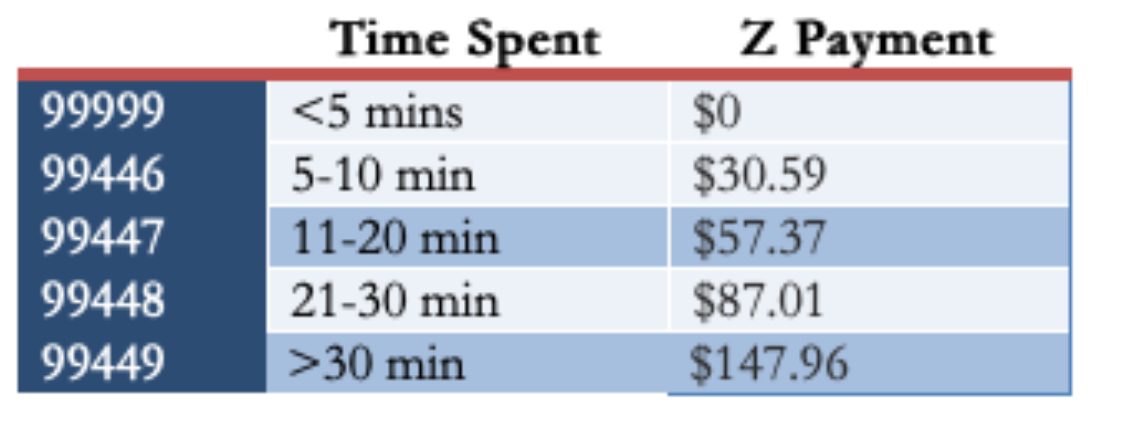

In a healthcare system where procedures dominate the payment landscape — the more, the better! — an advance in efficient patient care just can’t get the attention of the payers or the administrators holding the purse strings. Yes, there are billing codes for clinician advice activities without seeing the patient, but the net pay is poor (average 0.5-1 RVU, latest conversion factor $33.06/RVU), and the technical hurdles of getting reimbursement can be tricky to implement. Plus there’s this requirement:

THESE REQUIRE INFORMED PATIENT CONSENT! Since the consulting physician is not seeing the patient, the requesting physician must obtain and document informed consent.

And guess what? If you or another ID doctor ends up having to see the patient and do a consult on the case within a week, that “formal” consult can’t be billed! As a result, hardly anyone uses these codes, at least based on my emailing a variety of ID doctors in academic medical centers, and by the lukewarm responses to an online query.

So if we’re not billing insurance, how do eConsults get supported? Note I’ve used the common euphemism for money — support.

Here, our hospital system pays us for eConsults out of the Physicians’ Organization budget, a finite resource; they set the reimbursement at $50/eConsult when we started, an amount that hasn’t budged despite a substantial increase in the cost of living over the last decade. In addition, they declined our offer to expand eConsults for inpatients, even though we offered to expedite these to make discharges more efficient.

I queried a bunch of other ID doctors in a variety of practice settings about their payment models, and their responses were diverse (and fascinating). Some get paid a set amount, like our program. One does use the “interprofessional consults code” and makes do (unhappily) with the meager payments. Another uses these codes, but augments them to what seem to me to be much more reasonable rates:

(For the record, in my experience, most eConsults would be in the third or fourth category, occasionally fifth if they involve contacting the consulting clinician or a reference laboratory.)

The ID director at a “closed” healthcare system says they have no specific payment for eConsults, but that they are tied directly to the ID doctor’s job responsibility. He estimated that “all clinician-to-clinician advice for the on-call ID doctor, without direct patient contact, accounts for 3–5 hours/day” — a substantial time commitment! Finally, Dr. Allison Nazinitzky, who does ID locums work, shared with me that one of her telehealth contracts pays her $125 for an “interprofessional consult with note — a flat fee no matter how long.”

(Check out my interview with Dr. Nazinitzky. Her experience finding the true value of ID clinical care is dynamite.)

The medicolegal aspects of eConsults should be factored into any estimation of the value of the program. eConsults may reduce medicolegal risk for the referring clinician, but they substantially increase it for the specialist taking it on. Why? As noted in an excellent review of the legal risks of curbside consults, this is because we are now explicitly reviewing the patient’s chart and providing specific advice:

The closer a physician gets to providing very specific information—what dose to start with, when to draw labs and what other kinds of studies to get, and what to do specifically with a particular patient—the closer that physician is coming to being part of the care team, as opposed to just providing general information.

Despite the boilerplate language we insert at the end of each note indicating the limitations of eConsults, this will serve as little protection if a suit is filed. As part of the care team, our names can be included in any filed suit. And even if we are later dropped because we never saw the patient, the process itself can be long and painful.

So what’s the solution? I say include these advice services as part of what constitutes the job of a clinical ID doctor — give us appropriate RVU or full-time equivalent (FTE) credit for it — and make it commensurate with the time, value, and medicolegal risk associated with the service.

And if that doesn’t happen, let’s do what Dr. Andrew Pavia recommends, in my response to the query about whether he uses the interprofessional consults codes:

In other words, stop doing eConsults until they’re properly supported. Seems like a good plan!

November 23rd, 2023

Giving Thanks — This Time to You, Readers of This Thing

Louie with his favorite dessert plates

Most years around this time I post some ID-related things to be grateful for — a research advance, a nice shift in epidemiology showing fewer people are sick and more are living longer, a new drug approval we’ve been eagerly awaiting. That kind of thing.

Last year, for example, it was gratitude that mpox had come under control (fingers crossed). That dolutegravir and bictegravir were holding up just fine. That Covid-19 finally seemed to be trending toward true endemicity (second pair of fingers crossed). And a quick comment about a certain social media site that remained a “wonderful and entertaining place to learn”, chaos at the top notwithstanding (yeesh, still holding out hope).

This year, I’m doing something different.

I’m going to thank you, whoever’s out there reading this thing, for sticking with it all these years. I’m truly grateful for your emails, your comments, your feedback, our chats at professional meetings, but most especially, for your eyes just reading this. Face it, if no one were reading these posts, I highly doubt the fine people at NEJM Journal Watch would continue supporting it. So thank you so much, and keep reading!

(Actually, if no one were reading it, I’d probably be writing something somewhere anyway — that’s how I’m wired — but you know what I mean.)

At this year’s IDWeek, at the Medical Education Community of Practice meeting, I met Dr. Priya Kodiyanplakkal, an ID doctor from New York. In the pre-meeting chat, she gave me the greatest compliment I could imagine about this blog, one she later kindly posted in this convention center lobby photo:

What she said is exactly what I’m trying to do — to convey what it’s like practicing clinical ID, the “everyday realities of being an ID physician” for all of us out there doing it.

And while I can’t know exactly who the readers are, I know from the numbers that it’s not just ID docs — it’s a much larger group of healthcare providers, people who find ID interesting, or enjoy my takes on broader issues of clinical practice (e.g., rants against fax machines, ABIM recertification, CME requirements), or just want to see the latest photo of Louie.

(My wife Carolyn purchased those dessert plates from a store which had them on sale in a remainder bin. Can you believe it?)

But whoever you are, I do know that we’ve built a remarkably nice, smart, and civil community. At one of our editor’s excellent suggestions, we have a moderated comments section, meaning we review the comments before posting. With few exceptions most of them are thoughtful and not at all nasty — it’s uncommon that we have to ding one for breaking the site’s rules. A rarity for internet communication!

Speaking of the editors, thank you also to the three of them, who take turns reviewing each post before it appears, scanning for typos, unclear prose, and unauthorized material. They’ll probably not be happy with me that this one went up without their approval, but this is a national holiday, after all — don’t want to bother them. Plus, I can guarantee that I hold all the rights to that photo at the top.

So after starting writing here in 2008, and 877 posts later, I’m still at it — thanks to all of you readers.

Hey — you can still buy these plates on eBay, in case you’re wondering. Happy Thanksgiving, everyone!

November 16th, 2023

Being a Good Doctor — Why Are the Simple Things So Hard?

The simple things that make someone not just a doctor — but a good doctor — can slip away from us when we’re too busy, or tired, or preoccupied, or hungry. That’s why it’s wise periodically to be reminded of the “soft skills” that, while individually not tricky, together make a huge difference in how patients perceive us.

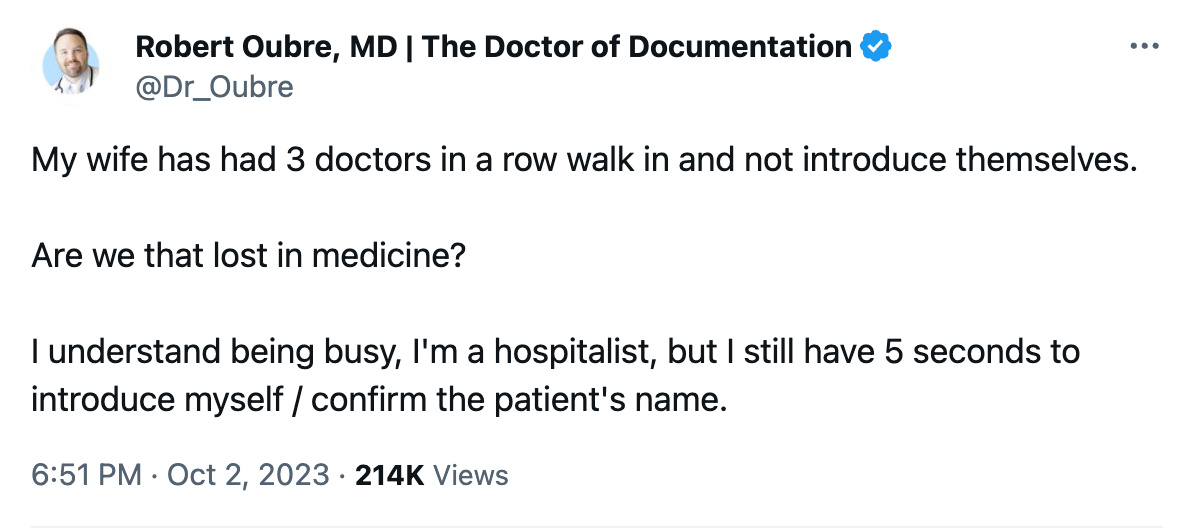

“Soft skills,” by the way, is the term coined recently by Dr. Robert Oubre, a hospitalist from Louisiana who specializes in Clinical Documentation Improvement, or CDI. Periodically imparting his wisdom on social media and in his newsletter, he recently posted something entitled, “Preventing and Protecting Against Lawsuits.” Here’s what one lawyer told him was a critical part of avoiding legal trouble during patient care:

You should practice in a way that causes your patients, and everyone you work with, to like you.

Be likable! How sensible. Because beyond lawsuit protection, I’d argue these soft skill make up critical components of patient care, and legal risk-reduction is just a corollary benefit.

Here are some of those skills he cites, in bold, followed by my comments — it’s a great list. He writes from the perspective of hospital care, but a lot of them transfer over to the clinic.

Sit. In the hospital, patients are often in bed, sometimes in a chair, but hardly ever standing. Get on their level. This small physical act greatly increases their sense that you care about them and that you’re giving them time. Logistically, it’s not always easy — family might be visiting, chairs might be occupied or have stuff on them, the room might be architecturally challenging. But try to make it happen when you can.

Call. Find out who they’ve listed as their designated family member or friend to help out, and keep that person updated. We had the importance of this action driven home to us during the dark days of the pandemic, when families couldn’t visit. One time-saving strategy is to have the patient call while you’re rounding in the room or during the office visit, and put their family member on speaker phone.

Ask, “What questions do you have?” rather than “Do you have any questions?” The former invites questions, the latter subtly discourages them.

Introduce yourself. Patients meet a ton of clinicians during their hospitalization, especially if it’s a long and complex one. Coverage changes, weekends and holidays happen, specialists aplenty get called in. For many services, the era of working extended blocks of time of consecutive days is long gone. So it never hurts to remind patients who you are — and do it repeatedly, as with rare exceptions, we are terrible with names. (You lucky few out there who are good with names are fortunate indeed!) During his wife’s recent care, Dr. Oubre posted the following — that empty, confused feeling when people fail to introduce themselves:

Use the patient’s name. There’s really no excuse for not greeting the patient by their name — after all, we all know it, it’s right at the top of the medical record. So use it — “Good morning, Mr. Smith”, “Hello again, Ms. Lopez”, “Hi, Mr. Gupta, how was your night?”, etc. (Then introduce yourself — again. See above.) If the name is unfamiliar or hard to pronounce, ask them how to pronounce it, and do your best to get it right. Plus, on those occasions when a patient changes rooms, this action provides another check that you’re not about to take a history, do a physical exam, or worst of all, do a procedure on the wrong person. (Yes, it happens.)

Acknowledge others in the room — and find out who they are. I added that last bit. Both are crucial. Let’s imagine you walk in the room, and your patient (a man) is accompanied by a woman. Try this script: “Hello Mr. White, I’m Dr. Schwartz, nice to meet you.” Turn now to the woman, and say, “And who do we have with us today?” Not — “… and is this your wife?” Most of the time it will be the spouse or partner — but not always. Everyone has made the mistake of assuming it’s a spouse, only to find out it’s the patient’s friend, or sibling, or parole officer, or daughter (ugh), or mother (ugh again). If you haven’t yet made this embarrassing generational error, learn from our mistakes and don’t do it yourself.

Corollary to this point: On rare occasions, your patient doesn’t want the extra person there, but has been forced (or even bullied) into it. Give them an opportunity to be alone with you, by asking if they’d like the person to be there during the history or during the physical exam. For young adults (ages 18-25, give or take), I typically allow the parents in the room during the initial history, then ask them to leave during the physical at which time I can ask more delicate and private questions.

American Theater Poster, 1899

Mention the NAME of other doctors that are caring for them. While you may not be able to do this for all the doctors, try at least to name the primary attending physician, or in the outpatient setting, the referring clinician. And don’t just mention their name — tell them you’ve been communicating. “I heard from Dr. Li, your primary care doctor, that you had a positive TB blood test and had some questions”, or “I know from reviewing your chart that Dr. Aslam thinks you might need a change in antibiotics.” With so many people involved in a patient’s care, it’s critical to inform them that everyone is working as a team to help them get better — “Establish a team-work mentality” is another one of Dr. Oubre’s soft skills, and this strategy affirms this team work.

Smile. Listen. Affirm their experiences. One patient I saw with severe asthma told me how grateful she felt when one of our gifted pulmonologists said something like, “That must be very scary for you” when she described the sensation of having an asthma attack. Remarkably, in all the years of seeing various clinicians, no one had ever mentioned that before. Having this doctor acknowledge her fear went a long way to establishing their very successful long-term care plan.

For our new HIV diagnoses, we make sure to acknowledge the feelings they have when they find out their HIV test returned positive — something along the lines of, “It can be hard to hear that the test is positive.” Then pause, and let them speak. We can then quickly move on to reassure them that the diagnosis is no longer a death sentence, that treatment can lead to a long and normal life, and that we’ll help them adjust to this new reality of having a chronic (but treatable!) condition.

Follow up on promises. My wonderful (and still dearly missed) late colleague Paul Farmer took this to heart more than anyone I’ve met. No matter how busy or crazy his schedule, if he told a patient he’d be back to hear more of their story, or to give them boots, he’d do it. (Here’s the boots story, #2 in the list.) I’m not saying we need to buy everyone boots — but his actions stand out as a good model for what we should aim for.

Be approachable to nurses. This statement, of course, applies to all the members of the care team. There’s no room in good patient care for outdated hierarchies or authoritarian actions. The nurses, social workers, pharmacists, front desk staff, the person delivering the food tray, transport personnel — we’re all there to accomplish the same thing, which is to get our patients better. The more we acknowledge and validate the others we work with, the better we’ll do.

Remember to look at them — not just the computer. Sure, we can consult the electronic medical record during the visit — just tell them that’s what you’re doing, and even apologize if you need to go on a lengthy search. Or invite them over to do it with you! But staring exclusively at the computer screen and typing while seeing a patient is a surefire way to create distance between “us” and “them.” And yes, I added this one to the list, as it’s long been a pet peeve of mine.

A non-medical person reading the above might think this stuff is easy. What’s the big deal? But trust me, the fact they seem so obvious stands in sharp contrast to just how difficult they are to do consistently, in particular when external demands weigh in as distractions.

But try we must — not only to avoid lawsuits (the original purpose of Dr. Oubre’s excellent list), but just to be a kind and caring doctor.

Anything left out you want to mention?

It certainly never hurts to ask about pets — people love talking about their pets, especially if they have a special talent.

October 31st, 2023

HIV Research Highlights from IDWeek 2023

Having already featured an important non-HIV clinical research study from IDWeek — the amazing ACORN trial — I turn now to a grab bag of HIV-related studies, a veritable Halloween treat bag full of them.

Having already featured an important non-HIV clinical research study from IDWeek — the amazing ACORN trial — I turn now to a grab bag of HIV-related studies, a veritable Halloween treat bag full of them.

(Note to self: What’s with that “Halloween treat bag” reference? Couldn’t you come up with a less awkward way to link this content with the posting date?)

Note acknowledged. I’ll think of something snappier for next year!

Here are the studies:

Compared to placebo, semaglutide markedly reduced weight and total body fat in PWH with lipohypertrophy (#1984). Interestingly, there was no effect on ectopic fat in the liver and pericardium, locations which correlate with some adverse outcomes. Lead investigator Grace McComsey (who has led several remarkable single-center studies on metabolic issues) cautioned that lipoatrophy might worsen with this treatment, potentially a concern in particular for our older patients who received thymidine analogue drugs (ZDV, d4T) in the distant past.

In a large (n=225) retrospective cohort study, GLP-1 receptor agonists were more likely to lead to > 5% weight loss in those with higher baseline BMI and longer duration of treatment (#1983). Dulaglutide appeared less likely to achieve this weight loss than semaglutide and terzepatide. What does it say about the current state of outpatient HIV management that these two studies of GLP-1 agonists were featured oral abstracts at an ID meeting?

One dose of penicillin is as good as three for early syphilis (#2889). During my ID fellowship, a local expert strongly opined that 3 doses were necessary, especially with concomitant HIV. Not so say the results from this multicenter randomized trial, where response rates were comparable with 1 vs 3 doses, including in the 67% of study participants who also had HIV. Data confirm what is recommended in treatment guidelines.

A bunch of studies looked at various comparisons between BIC/FTC/TAF and DTG/3TC, two highly popular and effective regimens. In an interim analysis of a randomized clinical trial comparing remaining on BIC/FTC/TAF vs. switching to DTG/3TC, the switch strategy was non-inferior at week 24 (#1603). There were more discontinuations in the DTG/3TC arm, explained in part by the open-label nature of the study (ascertainment bias). As with the TANGO and SALSA switch studies, switching to DTG/3TC did not result in weight loss. Interestingly, a person who remained on BIC/FTC/TAF experienced virologic failure at week 12, with detection of M184V and G140S mutations. I believe this is the first report from a prospective study of any participant experiencing virologic failure with INSTI resistance on this regimen — wonder if there was prior treatment failure on RAL or EVG.

Switching to BIC/FTC/TAF (n=3527) or DTG/3TC (n= 2213) in clinical practice maintained virologic suppression, with very rare instances of virologic failure (#1023). Only two and three cases of virologic failure occurred, respectively, after over a year of follow-up. Since this is a non-randomized study, the patient characteristics differed between those getting BIC/FTC/TAF vs. DTG/3TC: BIC/FTC/TAF recipients were significantly more likely to be Black, on government insurance, have experienced prior virologic failure, and have a lower CD4 count; those on DTG/3TC had a lower eGFR. Regimen discontinuation occurred statistically earlier with DTG/3TC versus BIC/FTC/TAF.

Related to the above, clinicians gave different reasons for switching to BIC/FTC/TAF vs. DTG/3TC (#1570). For BIC/FTC/TAF, these reasons were inconsistent healthcare visit attendance, adherence challenges, substance use, HBV coinfection, or viremic on current regimens. For DTG/3TC, concerns about low eGFR or excess weight gain motivated the switch. For the weight issue, note that none of the switch studies of DTG/3TC have shown any difference between BIC/FTC/TAF and DTG/3TC when it comes to weight — and IDWeek provided another one (see #1603 above).

Out of 1843 PWH who started CAB/RPV in a US-based cohort, 229 (12%) had a detectable viral load at treatment onset, a strategy outside of licensed indications (#1028). For 93 of them, the viral load was > 200, so true virologic failure. Virologic suppression was achieved in 82% overall, with 4% experiencing virologic failure. There was scant data on pre- or post-treatment resistance, or more importantly why the clinicians chose this regimen — especially since the median CD4-cell count was around 500! As noted previously, I strongly believe that if we’re using this treatment for virologic failure, we should limit it to those with low CD4-cell counts at very high risk for disease progression.

Data from a claims database suggests that adherence and persistence on injectable CAB/RPV is better than oral ART (#1024). Adherence was generally high for both strategies, but significantly higher with CAB/RPV using the 90% adherence threshold. Data are both reassuring and perhaps not surprising, given that CAB/RPV requires fewer doses, our generally careful selection of candidates for this strategy, and the intense efforts to keep those who are on it engaged.

In a pilot study, 33 patients successfully received CAB/RPV at home (#1027). Remarkably, a single nurse drove to homes in a 3000 square mile region. The study sent the medications by mail, with instructions for home refrigerator storage and pre-visit preparation by the patients. This is a good proof-of-concept study, but for obvious reasons not sustainable by most healthcare systems. And while I once thought that pharmacies would be a good location for getting CAB/RPV, the commercial pharmacies in our region are now massively understaffed and overwhelmed.

In a prospective cohort study, women with low-level viremia had higher rates of treatment failure, with a trend toward more multi-morbidity (#1025). These results are similar to those observed in cohorts made up of mostly men. Management strategies are still uncertain, aside from redoubling efforts at ensuring adherence and using high resistance barrier regimens.