An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

October 25th, 2014

What Makes An Ideal Applicant for a Fellowship in Infectious Diseases?

We’re at the tail end of the ID fellowship interview process, and am pleased to report we’ve seen some outstanding applicants.

They know that our field is the most interesting in medicine, and they view our recent “Epidemic of Epidemics” — to coin a phrase from John Bartlett to describe all this activity (Ebola, MERS, Enterovirus D68, etc.) — as not as a deterrent, but instead an important and fascinating challenge.

Face it: if it’s in the news these days, and it’s health related, there’s a good chance it’s an ID topic. Take a look at this, for example:

In that spirit, I thought I would share a recent email exchange with a former colleague:

Hi Paul,

I just started as program director for an internal medicine residency program in Illinois. I have been doing some career counseling with the residents, and have decided to email specialists I have known along the way with the following two questions about their field:

1. What are the characteristics of an excellent candidate for your fellowship?

2. How important is research experience? Bench vs. clinical?

Hope you’re well,

Craig

Here’s my response:

Hi Craig,

We look for the top clinical people, in particular those who relish the “great case” and love taking detailed patient histories (you know, does the patient have any pets, or has he/she been spelunking). They should definitely also enjoy bread-and-butter inpatient ID (which includes plenty of surgical/routine stuff as well as the fascinomas) and HIV and the complexities of transplant patients. It’s great when they express enthusiasm for the minutiae of microbiology (such as has Strep bovis changed its name?) as well as anti-infective agents (another cephalosporin — ceftolozane/tazobactam — is coming soon, am sure you’re thrilled). And they should want to be the local “expert”on all the newsworthy stuff that fills our days.

As for the research, it’s more important that they have a strong idea of what they would like to do. Yes if they have research experience, that’s a bonus, but it’s not required.

And they shouldn’t be going into ID for the $$$, or if they love to do procedures, because if they are, they are not very smart.

Nice hearing from you after all these years!

Paul

Sound about right? And what’s the story with Strep bovis anyway?

Speaking of pets and surgical infections, this one never gets old:

October 19th, 2014

Almost Filovirus-Free (That is, Ebola-Free) ID Link-o-Rama

If you’re an ID doctor right now, the filovirus of the moment Ebola is consuming a big chunk of all of your non-clinical time — and this is particularly true for those heavily involved in Infection Control, who are spending every waking hour responding to public hysteria, to various clinicians who seem to have all the answers, and to ever shifting federal, state, and regional guidelines. Thank you for doing this!

If you’re an ID doctor right now, the filovirus of the moment Ebola is consuming a big chunk of all of your non-clinical time — and this is particularly true for those heavily involved in Infection Control, who are spending every waking hour responding to public hysteria, to various clinicians who seem to have all the answers, and to ever shifting federal, state, and regional guidelines. Thank you for doing this!

So as change of pace, I bring you this Almost Filovirus-Free ID Link-o-Rama, though this ever-challenging epidemic does make an appearance at the end.

- There’s been a bit of controversy on mandatory flu shots for certain healthcare workers at a certain New England hospital, whatever that could be. In response, I offer this brilliant Mark Crislip essay (it’s actually more of a tirade), which is republished annually by him and quoted by others, and falls easily into the must read now category — you will laugh, you will cry, and if you’re a health care provider you will nod your head with recognition many times, wishing you had the guts to write it yourself.

- Speaking of vaccines, this coverage of national immunization rates for children in kindergarten reminds us that while vaccine refusers can dangerously cluster within communities, overall the USA is still doing quite well — which is why our outbreaks of vaccine-preventable illnesses are comparably small compared with Western Europe. School regulations requiring vaccination before school entry is policy for the public good at its best — it’s what you’d expect an ID doctor married to a pediatrician to say, but so be it.

- Enterovirus 68 — which is now known as Enterovirus D68 — is feeling a bit left out of the Panic Virus Hysteria, but here’s some good news: there’s a faster, better test to diagnose the infection, which will no doubt give a much better sense of the full spectrum of disease, and whether it is truly linked to neurologic syndromes.

- Kudos to my friend, colleague, and co-ID fellow (don’t ask when) Libby Hohmann, whose study of … um … ingesting frozen poop pills (that’s the easiest way to say it) for C diff points to a future treatment of this nasty condition. Sure beats having a colonoscopy (prep and sedation) or a nasogastric tube (mega-yuck) for delivery of the required donor material.

- On the inpatient ID side, Staph aureus MICs may not matter after all. If you combine this result with the lack of clinical studies correlating vancomycin levels with outcome, and the fact that every ID fellow spends a big chunk of his/her energy chasing these levels until they are perfect, can we have some sanity on this vanco level issue please?

- And while we’re talking about our oh-so familiar foe Staph aureus, and in particular MRSA, this editorial suggests we reconsider patient isolation for this infection and for VRE. Seems it’s probably unnecessary — with several major medical centers (Cleveland Clinic, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Detroit Medical Centers, others) already stopping this practice. Boy that would be liberating.

- That editorial was part of a fun-packed JAMA issue that was completely devoted to Infectious Diseases, including a study showing that around half of all hospitalized patients receive at least one dose of an antibiotic. And the most commonly prescribed drug? Vancomycin, followed (in order) by ceftriaxone, piperacillin-tazobactam, then levofloxacin. I wonder what proportion of patients admitted to a medical service get a cardiac ECHO?

- Guess what? Measuring CD4 cell counts in stable HIV patients on suppressive treatment doesn’t influence treatment decisions. No surprise. The problem, of course, is convincing our patients that the test we’ve been doing for all these years is no longer relevant — easier said than done!

- OK, Filovirus time. The policy of treating all US Ebola virus disease patients in special biocontainment units has not as far as I can tell been formally enacted, but that’s what’s currently happening. There’s been some confusion about the capacity our system has for doing so, as not all the beds in all the units can be occupied simultaneously, but it seems that it’s a grand total of 11 beds — the NIH has 2, and Emory, Nebraska, and Montana each has 3.

Department of Shameless Self Promotion: You can now sign up and get notification about the latest post by putting your email address in the box on the right. Not saying you want to do this, just that you can.

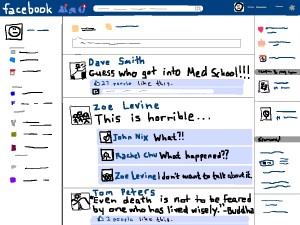

And while we’re on the topic of self promotion, here’s a painfully funny takedown of egregious Facebook behavior. Don’t complain that you weren’t warned — because we’ve all been there, done that.

October 15th, 2014

Second U.S. Healthcare Worker with Ebola Further Underscores Urgent Need for Enhanced Preparedness — and Perhaps Designated Care Centers

If you’re like most of us, when you heard that a healthcare worker in Dallas had been diagnosed with Ebola virus disease, you assumed that the exposure occurred during his first visit to the hospital.

That is, before he was diagnosed with Ebola, and before infection precautions had been instituted.

But no, it happened after he was diagnosed, and isolated, and presumably when all the care providers were using infection prevention measures of some sort. The same is true for the second Dallas healthcare worker, and the nurse in Spain, and in none of these cases can a specific breach in precautions be definitively pinpointed as the cause.

Yes, the nurse’s union in Dallas is citing major problems with their protocols, and certainly there were issues in Spain as well. But regardless of what actually happened, these cases emphatically reinforce that safe care for Ebola virus disease is a monumental challenge. Which is why all of us ID doctors are on high alert for the time when such a case occurs, and why yesterday CDC stated they would send out an expert response team to any hospital that has a confirmed case — a decision that makes tons of sense.

I confess the magnitude of this infection control challenge did not fully strike me until last week — this is before the Dallas care providers were diagnosed — when I heard a fascinating, brilliantly clear plenary talk at IDWeek from Bruce Ribner, the doctor in charge of the Emory team that cared for two Ebola patients. If you have half an hour, I cannot recommend this presentation strongly enough.

There’s a shortened text summary here on the IDWeek website, and many of his slides can be downloaded here (they were used for a national teleconference yesterday).

A remaining question — should all Ebola virus disease patients be cared for in designated centers only? The CDC is actively considering this recommendation, which needless to say has huge ramifications for our healthcare system.

Your thoughts?

October 12th, 2014

Approval of Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir Was Expected, but Still Is a Huge Advance

As expected, the FDA just approved the first single-pill treatment for hepatitis C genotype 1, a tablet containing 400 mg of sofosbuvir (SOF) and 90 mg of ledipasvir (LDV). For those not following this story closely, sofosbuvir is the pan-genotypic NRTI polymerase inhibitor approved last December to much rejoicing — and controversy about the price. Ledipasvir is the first HCV NS5A inhibitor, and is only available as part of this combination.

The brand name is “Harvoni”, which sounds a bit like an exotic offering on a menu that you need to ask your waiter to explain — “Ancho chile-rubbed Niman Ranch pork chop roasted in soy, ginger, and sesame, served with pan-sauted garlic kale, and garnished with corn and pinapple-harvoni salsa.”

But even though the approval was no surprise, and the brand name will (like all of them) take some getting used to, there’s no denying this is a huge step forward for HCV therapy. Let me list some of the reasons:

October 6th, 2014

Back to School: Questions from “ID in Primary Care” Course

Just wrapped our our annual postgraduate course, “Infectious Diseases in Primary Care,” where each year we get together with primary care providers (doctors, nurses, PAs) and review what we hope are the most clinically relevant topics in ID.

And each year we get a great bunch of questions, some of which I’ve listed below (along with an attempt to answer them):

- I know the zoster vaccine is indicated for people who have had shingles. But how long should I wait after they’ve had it before giving it?

Of all the questions I get about the zoster vaccine — and trust me, there are lots of them — this is currently the most common by a long shot. (Ha!) Importantly, this question gives me a chance to praise one of the most practical sources of ID information on the internet, the authoritative and incredibly useful “Ask the Experts” section of the Immunization Action Coalition’s web site. Questions like these are posted and concisely answered by, you got it, experts! And here’s what they say on this particular one: “Administering zoster vaccine to a person whose immunity was recently boosted by a case of shingles might reduce the effectiveness of the vaccine. ACIP does not have a specific recommendation on this issue. But it may be prudent to defer zoster vaccination for 6 to 12 months after the shingles has resolved so that the vaccine can produce a more effective boost to immunity.” So there’s my answer. - What do you do when the new syphilis test [treponemal ELISA] is positive, but the RPR is negative?

Depends. First step is to send one of the classic confirmatory tests — we use the TP-PA here, but the FTA-ABS or MHA-TP would be fine too. If that’s negative also, you’re probably dealing with a false-positive ELISA. If it’s positive, and the patient has been treated before, you’re all set — the negative RPR means he/she is cured. But if they’ve never had treatment, then it makes sense to treat for late-latent syphilis. None of this, of course, is based on firm clinical data correlating these strategies with clinical outcomes — welcome to the world of syphilis diagnostics and therapy! - Sometimes patients request that we screen them for “every STD.” Would you include HSV serologies?

Type-specific HSV serologies are very reasonable to send when someone makes this request, provided there is up-front education about what the results mean. Specifically, if someone tests positive for HSV-2, they are considered to have infection with this virus and could potentially transmit it even if they’ve never had symptoms. Furthermore, the positive test can’t indicate when someone acquired HSV-2, and most emphatically says nothing about from whom. And in this context (screening), forget the HSV IgM — it’s a lousy test , with tons of false positives. - If someone can’t take doxycycline, and is allergic to penicillin, should I use azithromycin for treatment of Lyme?

Azithromycin is less effective for Lyme than other treatments (doxycycline, amoxicillin, cefuroxime), so I’d only use azithromycin as a last resort. (Because who wants to use a less effective treatment for anything, especially Lyme. Shudder.) If we really scrutinize those antibiotic allergies, of course, we often find that it’s something very vague or isn’t an allergy at all. (“My mother told me I was allergic, so I guess I’m allergic,” says the 50-year-old man, who confesses he’s not even sure what “allergic” means.) More than 90% — some studies say way more — of those referred to allergists who have “penicillin allergy” turn out not to be allergic based on skin testing. In other words, I can’t imagine a setting where I’d have to use azithromycin for Lyme, though maybe a few doses until you sort out the allergy (or not) issue would be reasonable. - A patient of mine had a positive PPD and a negative interferon gamma release assay (IGRA). She said she had a BCG as a child, and she has no symptoms. Which one is right?

Can you hit the “rewind” button on your clinical encounters with her, and send only the IGRA and skip the PPD? This is one of the settings where IGRA is preferred, the patient with a BCG immunization history, as BCG will not trigger a positive IGRA and might do so for the skin test. That said, now that you have one positive and one negative, there is no way to determine whether the PPD is falsely positive due to the BCG, or the IGRA falsely negative since no test for latent TB is 100% sensitive. In other words, there’s no gold standard, so you’re sort of stuck making a clinical decision. So here’s what I do — in patients with low risk for TB exposure, go with the IGRA, and say the test is negative. If high risk, especially if contemplating something that increases the risk of TB activation (such as TNF-blockers), go with the positive PPD, and, presuming the CXR is negative, prescribe preventive therapy. - I know that resistance to azithromycin has increased, but does this mean it actually is less effective than other antibiotics for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia?

Way back when, before the existence of Z-paks and Zebra puppets and other brilliant azithromycin marketing, pneumococcal resistance to macrolide antibiotics was uncommon. However, the bug is now resistant to azithromycin around a third of the time in the US, with even higher rates in many other countries. While failure of treatment of otitis media with azithromycin due to resistance is well documented, the data with pneumonia are less clear — probably because the causes of pneumonia are more diverse, with a bunch caused by mycoplasma, some viral, some who-knows-what. Nonetheless, I’d be very concerned about using azithromycin as monotherapy for someone with fever, pleuritic pain, a lobar infiltrate, or other clinical features suggestive of bacterial pneumonia, and would definitely not rely on it alone for patients sick enough to be hospitalized. - The drug-drug interaction between statins and HIV drugs is scary — which one do you recommend?

You’re referring, of course, to the fact that metabolism of many statins is inhibited by ritonavir and cobicistat, which can lead to dangerously high statin levels. I’m a fan of using atorvastatin in this setting, and here’s why: it’s less dependent on cyp3A for metabolism than lovastatin or simvastatin, it’s more effective than pravastatin, the drug has been associated with all kinds of clinical benefits (practically every cardiologist on the planet is on it), and it’s generic. For your patients on ritonavir or cobicistat, just start with a low dose (10 mg daily) and titrate up as needed, stopping at 40 mg/day. If you want to face off with the Payor Police, pitavastatin (which has no cyp3A metabolism) is another reasonable option. - When is next year’s course?

Glad you asked! October 14-16 — mark your calendars! A beautiful time of year to visit Boston.

Hey, our course this year was held between two notable fall holidays for some of you (me) — so enjoy this video. And I totally agree with the “gateway drug” analogy!

September 28th, 2014

New FDA HIV Drug Approvals Unlikely to Have Much Impact, Unless …

If you’re an ID doc based in the USA, you probably received notice last week that two new HIV drugs were approved — cobicistat and elvitegravir.

And if you’re wondering what the big deal is, welcome to the club. In fact, the Canadians beat us to the punch with more significant approval, the co-formulated darunavir/cobicistat, branded as Prezcobix — which sounds like one favorite British breakfast cereal.

For the record, here are a few reasons why the FDA approval of elvitegravir and cobisistat will likely have little short-term effect on clinical practice:

- Elvitegravir is already available as part of TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI.

- Cobicistat is already available as part of the same single tablet regimen.

- If not coformulated, elvitegravir alone has no major advantages over raltegravir and dolutegravir.

- If not coformulated, cobicistat alone has no major advantages over ritonavir. (Though I gather the pill is smaller. Haven’t seen it yet.)

But — what if they cost less? Especially a lot less?

Then maybe.

September 24th, 2014

Quick Question: How Do I Fill Out This Tricky Patient Job or School Form?

From a long-term and highly respected colleague comes this challenging query:

Hi Paul,

One of my HIV pts, doing wonderfully well, is planning to enroll in a nursing program. She does not want to disclose her HIV status (fine with me), but the hospital requests a list of current meds which, of course, would blow her cover. My inclination is simply to leave the HIV meds off the list, but I asked our legal office who advises me not to do so — they say just decline to fill out the form. However, I don’t like that advice, since it essentially means my patient cannot enroll in the program. Of course I question whether the employer has the legal right to know all the meds, but I can’t change that in the short term.What sayest thou?

Miffed in Malden

Dear Miffed,

I completely share your frustration with these forms, which have bedeviled us ID specialists for decades. One of the more excruciating questions they sometimes ask is, “Does this patient have a contagious disease?” Hate that one; I’ve figured out that it’s best to interpret it as, “Does this person have a disease that would be considered contagious in the context of these job activities?” making it much easier to answer.

But the nursing program wants to know your patients medication list, which brings up the question of why. If they find out she were taking HIV meds — or psych meds, or immunosuppressive drugs, or five antihypertensives, or echinacea — would they reject her application? I hope not, as that would be highly discriminatory — people with these conditions can certainly work in healthcare provided they are medically stable. It’s not as if she’s applying to be an airline pilot, where the FAA has a very clear list of exclusionary medical conditions and medications. (At least I hope they do.)

But the nursing program wants to know your patients medication list, which brings up the question of why. If they find out she were taking HIV meds — or psych meds, or immunosuppressive drugs, or five antihypertensives, or echinacea — would they reject her application? I hope not, as that would be highly discriminatory — people with these conditions can certainly work in healthcare provided they are medically stable. It’s not as if she’s applying to be an airline pilot, where the FAA has a very clear list of exclusionary medical conditions and medications. (At least I hope they do.)

So yes, the form stinks. But in the meantime, you have to decide what to do, which leaves you with several alternatives — none of them perfect, but some clearly better than others.

- Decline to fill out the form. This is what your legal office advises, and while it may make sense legally, is it the right thing to do? Definitely not — in other words, I completely share your opinion. We overall want to be our patients’ advocates, especially for something that enhances their global well-being (something like enrolling in a job program). So if this isn’t the right answer (and it’s not), why did your lawyers give this advice? Let’s just say there’s a reason they went to law school, and we didn’t, and perhaps this example nicely sums up some differences between doctors and lawyers.

(Some of my best friends are lawyers. Really.) - Leave the medication section of the form blank. While this isn’t technically lying, it raises the uncomfortable possibility they will call you: “Dr. Miffed, this is Gladys Gleepster from Regional Community Hospital, and it’s about your patient Ms. Smith — you left a section of her health form blank. Could I fax this back to you so that you can complete it?” Then what are you going to do? Fess up that you did this intentionally? Continue to stonewall? Not a comfortable situation.

- Selectively leave the HIV medications off the list. In other words, lie about it. It’s a small lie, yes, and unlikely to hurt anyone, but a policy of “No lying on forms” is something we made official in our clinic years ago, and I strongly recommend it. It became particularly important back in the late 1990s, when some of our previously disabled patients had (miraculously) become quite robust on HIV therapy — it seemed (and was) deceitful to fill out forms stating that a patient “Can walk a maximum distance of one city block” when just that day they were boasting about finishing a strenuous mountain hike or a triathlon. Plus, there was that person who asked me for a letter granting him “automatic upgrades to business class, in particular on international flights” due to his “severe claustrophobia” that, as far as I could tell, only manifested itself when he flew coach. I suggested that he have this unusual problem verified by a psychiatrist before we could write such a letter, because “we can’t lie on forms.” Policy.

- Dump the form on the primary care provider. Yikes. As someone married to a primary care provider, who is figuratively looking over my shoulder as I write this, I emphatically state that this is definitely the wrong choice. (Though tempting. Sorry.) ID doctors may be dumped on with paperwork from homecare companies who insist that you resolve the final date of home antibiotics and, while you’re at it, please tweak that vancomycin level, but this is nothing compared to the deluge of forms PCPs get. Plus, many of our longitudinal HIV patients don’t have a primary care provider, so like it or not, you’re it.

- Write, “Patient prefers to keep this information confidential.” This, I think, is the best approach — especially if it’s preceded by your telling her that this is what you’re going to write. If she doesn’t like what you propose, tell her you “can’t lie on forms,” and she’ll most certainly come around to this being the best solution. Additionally, filling out the form this way will put the ball in the hospital’s court, perhaps even forcing them to reconsider the requirement that people list their medications before joining their nursing program. And wouldn’t that be nice if they changed it!

I said none of the solutions was perfect, but that’s my take. Any other ideas?

September 13th, 2014

In These Challenging Times for ID Doctors, a Little Comic Relief

I was passing a colleague in the hall the other day — he’s a general internist by training, now an important hospital administrator — and he briefly stopped me to get my take on the flurry of ID-related news bombarding the world right now.

Him: Hey, Paul, good to see you.

Me: Hi Jerry.

Him: Quite a time for you guys in ID, isn’t it. Did you read the piece in the Times on Ebola? On how it could mutate to become much more transmissible? Is airborne spread really a possibility?

Me: Yes, scary.

Him: And how about this enterovirus 68 situation? No cases in Boston so far, right? But how long before it gets here? That must be inevitable.

Me: Yes, scary.

Him: One more thing. We’ve spent every Christmas holiday the past few years in the Caribbean, this year we’re tentatively planning to go to a resort in the Dominican Republic. My wife wanted me to ask you about Chikungunya — any reason to be worried? Sounds like it’s a pretty bad situation down there.

Me: Yes, scary.

Now I was a bit less repetitive (and I hope more helpful) in my responses, but the message remains the same — this is quite the time for infectious outbreaks that are, in a word, “scary.”

Which is why it was a relief this past week to get the following comment on the blog, demonstrating that there are other things going on in the world besides hemorrhagic fevers, kids with severe respiratory disease, and febrile, joint-contorting sickness, and that furthermore, our site’s spam filter is not infallible:

“this article is fine but honestly all i care about is that black sabbath are the greatest group of all time.”

Thank you very much, glad you have your priorities straight.

And hat tip to Kristin Kelley for finding this brilliant comment in the comments folder, and even more so for having the presence of mind to alert me to it.

September 7th, 2014

It’s OK to Limit Who Prescribes HCV Therapy, but Insurers Shouldn’t Be Deciding

Some insurers would like to limit the prescribing of HCV treatment to gastroenterologists, hepatologists, or infectious diseases specialists. Not surprisingly, this doesn’t sit well with either the HIV Medicine Association (HIVMA) or the American Academy of HIV Medicine (AAHIVM), both of which have long acknowledged that some of the most seasoned HIV providers are generalists:

“There is no medical rationale for excluding some HIV providers from prescribing HCV medications,” said Donna Sweet, MD, AAHIVS, chair of the AAHIVM Board of Directors, an internist and HIV specialist. “HIV providers who have been treating HCV/HIV co-infected patients for years are uniquely qualified to manage potential drug toxicities and side effects stemming from combining treatment for HIV and HCV.”

I completely agree. Who is more qualified to prescribe HCV treatment, a provider with extensive experience managing HIV/HCV coinfection, or a gastroenterologist who has spent 90+% of his/her career practicing what some have called “lumen-oriented medicine” (see video below for explanation). And there are many ID specialists who do only inpatient ID consults — they would have as much chance correctly identifying ledipasvir, dasabuvir, and daclatasvir as winning the lottery.

The problem, of course, is that whether they say it or not, a motivation of the insurers is to delay treatment. I’m not so cynical to think it’s their only motivation, but it’s inevitably one of them. In the inherent conflict of interest that exists between medical insurance companies and expenditures for expensive short-term therapies, anything that delays treatment increases the likelihood that 1) other options will become available that drive down costs, or 2) the patient’s insurance will change, and it won’t be their problem anymore.

And as everyone learns in Econ 101, dollars spent in the future are worth less than those expended now — it’s called “discounting,” remember?

But is the concept of limiting who prescribes HCV therapy inherently wrong? Of course not — the benefit to the patient is so great, and the financial stakes are so high, it is eminently reasonable that only those qualified to do so should treat HCV.

It just shouldn’t be that the companies paying for the treatment, on their own, get to decide who the qualified providers are — they’re hardly disinterested enough to make this judgment wisely.

Everyone sing along now:

September 3rd, 2014

How to Choose a Case for ID Case Conference

As August becomes September, ID fellows across the land are becoming increasingly skilled, heading rapidly upwards on that steep learning curve that is the first year of fellowship. With one-sixth of the year already in the books, it’s a wonderful thing to see.

As August becomes September, ID fellows across the land are becoming increasingly skilled, heading rapidly upwards on that steep learning curve that is the first year of fellowship. With one-sixth of the year already in the books, it’s a wonderful thing to see.

One potential downside to this accumulating knowledge, however, is that they start to become familiar — they would say overly familiar — with the cases that make up the bread and butter of our field. “Another liver abscess? Big deal. I’ll get excited when the abscess is drained, and the cytology shows hooklets of Echinococcus — now that’s a case!”

(No one actually said that. It was a hypothetical paraphrase.)

Which is why in a month or two, they will start to wonder if they have any patients on their service that are case conference-worthy.

But the following guide will act as a reminder that yes, the ID service sees the most interesting cases in the hospital, and there is always something worth presenting at weekly case conference. Let’s take look at the options:

- The Amazing Case. These are obvious, so I will not belabor it, but typically they involve a rarely seen pathogen that somehow found its way to your hospital or clinic. Example: Just back from safari, a man came to the hospital with fever and headache — and lo, he had trypanosomes swimming around his blood smear. Needless to say, the ID fellow taking care of this man with African trypanosomiasis (a.k.a, “African Sleeping Sickness”) had no trouble selecting it for conference. That one was easy, so let’s move on.

- The Textbook Case. Every so often a patient has an illness that has not just a few, but every characteristic feature of a specific clinical syndrome — it’s as if they read a medical textbook before going to the doctor. Such cases have tremendous educational value, especially for residents and medical students — but really, who among us couldn’t use a refresher on what makes a case a “classic”? Example: The guy with several weeks of fatigue, anorexia, and low-grade fevers, physical exam with all the peripheral stigmata of endocarditis (Roth’s spots, Osler’s nodes, Janeway lesions — can you keep them straight?), a characteristic heart murmur, and a 1.5 mobile aortic valvular vegetation on the cardiac ECHO. Classic.

- The Funny Bug, Especially if in a Funny Place Case. Certain unusual microorganisms — funny bugs — can be conference-worthy on their own, especially if they have a great name (Staphylococcus lugdunensis) and/or a strong epidemiologic association (Capnocytophaga canimorsus = dogs, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae = lobsters, among other creatures). Now throw that funny bug into a funny (unusual) anatomic site, and bingo, you’ve got your case — even if it’s hardly a common manifestation of this infection. Example: A 31-year-old pregnant woman was admitted with abdominal pain and fever — ultimate diagnosis? Acute endometritis and bacteremia from Pasteurella multocida. Of course.

- The Now Quite Rare but Previously Very Common Case. Progress in vaccines has made certain conditions that were once standard business now quite unusual. As an example, I can count the number of cases of adult measles I’ve seen on one hand, or more precisely, on one finger. As a result, these cases are virtually always conference worthy, plus they give our more senior clinicians (ahem) a chance to wax eloquently about the bad old days. Examples: Virtually any vaccine-preventable illness (measles, mumps, Haemophilus influenzae invasive disease, even varicella). Bonus points for a case of rheumatic fever or late-onset neurosyphilis — not vaccine-preventable, but you get my drift.

- The Amazing New or Incredibly Confusing Diagnostic Test Case. Just the other day, a colleague from another hospital emailed me with excitement about a case of malaria. It wasn’t the case that was unusual — returning traveler from Africa, fever, etc. — but the fact that his hospital just got the Binax malaria rapid test, and he got the positive result back almost immediately. He was so excited he even took a picture of the positive test with his phone, sending it along with the email. Other examples: The first time you diagnose PCP with blood beta-glucan and or PCR. Or a case that makes you struggle through the C. diff testing quagmire. Or one that forces you to interpret the results of an EBV antibody panel. Someone with a dozen different Lyme tests — with one of twelve positive. (Ok, maybe not that last one.)

- The “Wow” Image Case. Way back in prehistoric times — meaning during my ID fellowship — one of our responsibilities as an ID fellow was to gather the relevant x-rays on our cases, not only for rounds, but also for case conference. It is no understatement that this was a huge challenge — these films were frequently scattered hither and yon throughout the various hospital buildings, so much so that we suspected that the place labeled “Radiology Film Library” was just a front for the hospital casino. And there seemed to be some hospital rule that all interesting brain CTs/MRIs were kept under the call-room bed of the neurosurgical chief resident. Today we have electronic access to all the images, plus everyone is carrying a camera, so we have this great opportunity to display these during conference. Examples: The initial rash of necrotizing fasciitis. Then the operative findings. The volleyball-sized tubo-ovarian abscess in the pelvis on CT scan, prior to drainage. (“Wow,” everyone will say.) The botfly removal (caution, observe at your own risk). You get the picture (ha).

- The Public Health Case. Let’s just imagine that someone shows up in your emergency department from Liberia/Sierra Leone/Guinea/Nigeria/Senegal. Never mind that they came in for a sprained ankle, someone is going to bring up the possibility of Ebola — especially when, on further questioning, the ankle person from Western Africa admits that 1) yes, they just visited family at home, and 2) yes, they too are worried about it; wouldn’t you be, especially since there’s a bit of headache/joint pain/fever. Since a sprained ankle and Ebola are hardly mutually exclusive, we’re talking prime conference material as soon as you get the consult — golden! Other examples: Any healthcare worker with tuberculosis. Or a restaurant worker with salmonella. You get the idea.

- The Management Dilemma Case. Despite our thick textbooks and nearly the entire universe of published papers available instantly on line, there’s a ton we still don’t know. I’ve written about a bunch of these clinical situations (here’s the list), and you can tell from the poll results that there really is no right answer — but that doesn’t stop people from having opinions. Another example: 60-year-old woman, professional cellist, has bronchiectasis and slightly worsening cough; a sputum culture is positive for M. abscessus, resistant (as usual) to all oral agents — she can’t imagine a life without playing the cello, and travels frequently. Should she be treated? If so, with what?

- The Everyone Else Was Messing Up Until We Came In and Saved the Day Case. All doctors love these EEWMUUWCIASTD cases, and they should never be underestimated as high-value material for case conference. In surgical conferences, they invariably present a patient languishing on the medical wards with abdominal pain, until “we took him to the OR and saved his life.” In ID conference, it takes a different form because we do no procedures. It usually involves some perfectly obvious (to us) historical detail that bingo, cracks a mystery case wide open — e.g., “So we simply asked her where she grew up and went to college, and when she told us Tennessee, we knew it was likely histoplasmosis”; or “They thought it was a simple community-acquired pneumonia, but we found out he had a twenty-pound weight loss, hemoptysis, and a history of an untreated positive PPD”; or “All someone had to do was ask her in Spanish/Vietnamese/Chinese/Haitian Creole what was wrong with her, and she told us”; or “He works as a touring semiprofessional golfer, had just returned from Mexico, and mentioned that he licks his golf balls before each drive for good luck.” These EEWMUUWCIASTD cases are tremendously gratifying — they reinforce the fact that we are the smartest doctors in the hospital, plus they make us feel better about the inverse correlation of intelligence with annual income.

I hope the above examples are a reminder that not all ID consults are decubitus ulcers and ICU fevers.

And if I left out a category, please let me know!