An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

August 1st, 2015

Ten Reasons to Attend Our “Infectious Diseases in Primary Care” Course

With an up-front apology for the shameless plug — sorry! — here are 10 great reasons to attend our annual postgraduate course. It’s called Infectious Diseases in Primary Care, and takes place October 14-16 here at the Fairmont Copley Plaza Hotel in Boston.

With an up-front apology for the shameless plug — sorry! — here are 10 great reasons to attend our annual postgraduate course. It’s called Infectious Diseases in Primary Care, and takes place October 14-16 here at the Fairmont Copley Plaza Hotel in Boston.

- All the topics are clinically relevant to day-to-day practice. Look at these topics! There’s a strict ban on basic science research (unless it’s relevant to patient care). Slides depicting gels or other complex lab experiments are prohibited.

- The faculty are all active in patient care and love to teach. Particular call-out to my long-time clinical mentor, Jamie Maguire. But they’re all great.

- Paul Farmer will be in the house. You can then say you saw him before he won the Nobel Peace Prize. (That’s my prediction. He’d never say this.) Plus, when he’s standing right next to me, it will be proof that we are not identical twins. More on Paul here. (Forgive the dated Tiger Woods analogy, it meant something at the time.)

- Get your ID questions answered, and more. I’ve periodically featured these questions since they are so interesting — here are some from last year’s course, for example. If you attend, ask away! We’ll do our best to answer.

- Keep your ID knowledge up to date. New immunization guidelines? New STD guidelines? New antibiotics? New HCV drugs? New outbreak in some travel location? No problem, we’ve got it covered. Let the record show we’ve been predicting this chikungunya thing for years.

- Fall is the best time to visit Boston. Like all locals, I’ve spent many hours complaining about Boston weather — not October weather, however, which is probably our best month. Comfortable days, cool nights, crisp blue skies, low humidity, fall foliage, local apples,

Red Sox in the playoffs.(Oops. Probably not that last one this year, sorry.) Fall in New England is simply wonderful. - The Fairmont Copley Plaza is a gorgeous hotel, with a perfect downtown location. Walk everywhere — restaurants, shopping, historic sites, picturesque neighborhoods. More about the venue here. Plus they have adorable black labs holding court in the lobby.

- Syllabus updated each year. Available both electronically and, for a small extra fee, print.

- “Name the Diagnosis” photo quiz, with a special prize. We’ll post some images of interesting and/or exotic infectious diseases — dirifilariasis in a human, for example — and ask you to name the diagnosis. The person with the most correct answers takes home a special ID-related award. Plus, you can impress your friends.

- Meet your CME requirements. It’s Harvard Medical School, after all — The Stanford of the East. Here are the details — we’re accredited by ACCME, the American College of Family Physicians, the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, the European Continuous Medical Education Council, and the Interplanetary Society of Postgraduate Medical Studies, which is based on Mars. (I made that last one up.)

There, ten reasons. Plus an added bonus — the candy that falls from the ceiling at the end of each lecture is yours to keep, which comes in handy for Halloween!

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TRGkEDADmRU]

July 26th, 2015

Really Rapid Review — IAS 2015, Vancouver

Vancouver will always have a special place in HIV treatment history. It was here, in 1996, that many of us first saw the potential of combination antiretroviral therapy to control this disease.

Vancouver will always have a special place in HIV treatment history. It was here, in 1996, that many of us first saw the potential of combination antiretroviral therapy to control this disease.

Specifically, Study 035 of AZT, 3TC, and indinavir (presented by Trip Gulick) demonstrated the astounding finding that triple therapy induced sustained virologic suppression and dramatic immunologic improvement.

Could it be that not everyone would eventually die of AIDS? Optimists certainly felt so — and indeed they turned out to be right.

It was only natural, then, that Trip would be given the chance to give an overview of HIV therapy at the conference — he did a terrific job of reviewing “What to Start,” with a summary of where we’ve been, where we are today, and where we might be going.

(And no, he didn’t sing.)

But what about new research? Without having the density of new material presented at CROI — something of a relief, really, during these summer months — the IAS 2015 conference still featured many interesting papers, some of which I’ve summarized in this Really Rapid Review™. I refer you to the (kind of clunky) conference website for the full abstracts and slide sessions; below I’ve listed the abstract numbers, because I can’t figure out how to link the abstracts.

- Long-term “remission” in an infected adolescent without ART. Got to start with the story that (inexplicably) got the most press: A perinatally infected child stopped HIV therapy (or more accurately, family stopped therapy) at age 6. Patient is now 18 years old and has had a detectable HIV viral load only once since stopping treatment. Remission? Or just an HIV controller? You decide, but I’m going with the latter, and no, the investigators did not use the word “cure” — which hasn’t stopped the media from tossing it around freely. [MOAA0105LB]

- HPTN 052 final results. In the landmark study that proved HIV treatment prevented transmission, we now have evidence of eight linked transmissions from people on HIV therapy to their partners — and all occurred either early in HIV therapy (before suppression) or during treatment failure. In other words, zero transmissions from participants with stable virologic suppression. Excellent news! [MOAC0101LB]

- And while we’re on the topic of landmark trials, Jens Lundgren presented the results of the START study on the very same day it was published in a highly prestigious medical journal. Key takeaways: HIV therapy is beneficial for patients with CD4 > 500 in preventing both AIDS complications and, in developed countries in particular, non-AIDS complications (mostly cancers). And note that most of the clinical events happened when the CD4 was > 500. [MOSY0302 — but read the paper!]

- In a large, randomized, double-blind trial done exclusively in women, elvitegravir/cobicistat/FTC/TDF is superior to TDF/FTC, ATV/r. Amazingly, the study (called WAVES) was given a poster and not an oral presentation — a completely inexplicable oversight given 1) it was a well-done study with an important result, 2) there were no other large randomized treatment trials at the conference, and 3) women have been terribly underrepresented in many recent clinical trials. Plus, the late-breaker posters were placed in the poster hall equivalent of Siberia, way over at the far edge of the room. Bizarre. [MOLBPE08]

- This presentation included a series of remarkable figures on proportion of people with HIV who are diagnosed, on treatment, and virologically suppressed. For the record, the USA is third in percentage diagnosed (86%), ninth in successfully treated (30%) — one whole percentage point above Sub-Saharan Africa. [MOAD0102]

- Three switch studies demonstrate the potential benefits of switching to elvitegravir/cobicistat/FTC/TAF (tenofovir alafenamide). 1) A large randomized trial compared staying on current regimen (TDF/FTC plus EFV or ATV/r or EVG/COBI) to switching, and the switch was overall superior [TUAB0102]; 2) Patients with chronic hepatitis B coinfection maintained or improved hepatitis B control [WELBPE13]; 3) Patients with stable chronic renal insufficiency (eGFR as low as 30) had stable renal function after the switch [TUAB0103]. In all three studies, switching from TDF-based treatment led to improvements in renal and bone parameters, with small increases in lipids. This “ECF-TAF” regimen is currently in the late stages of FDA review.

- In this large Spanish cohort study, TDF/FTC/EFV given as a single tablet was better virologically and economically than 1) other multi-pill regimens, 2) the same regimen given as multiple pills. Not a controlled study, but strongly suggestive of the benefits of coformulation nonetheless. [TUPEB264]

- In the aggregate ACTG clinical trials data that demonstrated an excess of suicidality for those randomized to EFV-containing regimens, 75% of participants participated in a genetic substudy. When these subjects were analyzed based on genetic predictors of of EFV metabolism, those with the slowest clearance of the drug had the highest relative risk of suicidality. These data do strengthen the findings from the original paper. (Disclosure: I’m a co-investigator.) [TUPEB273]

- In virologically suppressed patients receiving a boosted PI plus 2 NRTIs, switching to the two-drug regimen of DRV/r + RPV maintained virologic suppression as well as staying on the baseline regimen. Small sample size alert (n=60), so consider this a pilot study only. [TUPEB270]

- Another case report of resistance to dolutegravir in a treatment-experienced patient, with emergence of the R263K mutation. Additional integrase mutations emerged with ongoing failure, leading to a 5-fold loss of DTG susceptibility. Note that at baseline, the patient (a 12-year-old perinatally infected child) had no detected NRTI mutations (though extensive prior ART), and though treated with TDF/FTC + DTG, oddly did not select for RT mutations. This case (and those from the SAILING study) notwithstanding, resistance to DTG remains rare event — though it does happen. [TUPEA068]

- At 24 weeks in a phase II randomized double-blind study, the investigational NNRTI doravirine is comparable to EFV with a lower incidence of CNS side effects. Though the 24 week results for the < 40 cop/mL result seem unimpressive for both arms (around 70%), this is due to the patients with high baseline viral loads still having low-level viremia — no resistance detected in either arm, HIV RNA still declining. Two phase III studies of doravirine are underway. [TUAB0104]

- BMS-955176 is a second-generation maturation inhibitor that has activity even against viruses “resistant” to the first-generation drug in this class, bevirimat. In a small randomized trial, reductions in HIV RNA were comparable with BMS-955176 plus atazanavir to a standard-of-care regimen of TDF/FTC, ATV/r. A larger study of this two-drug combination is planned. [TUAB0106LB]

- In a large claims analysis of newly-diagnosed patients in the USA, the rate of comorbid conditions (hypertension, diabetes, CV, renal disease) was higher in 2013 than 2003. Not surprisingly, rates of these conditions were particularly high in the Medicare group. We HIV specialists really need to buff up our management skills as our population of patients ages! Maybe get to use the shiny new lipid lowering tool! Can you say “proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9”? [MOPEB157]

- Neither DRV/r or EVG/COBI/FTC/TDF induced insulin resistance over 14 days in this normal volunteer study. LPV/r did. [TUPEB105]

- Remember the regimen of simeprevir and sofosbuvir for HCV? That was briefly the preferred interferon-free regimen for HCV genotype 1 — way back when in early 2014, ancient history — based largely on results of the small COSMOS trial. Here the OPTIMIST-1 and 2 studies give a more precise estimate of efficacy of “SIM-SOF” in HCV monoinfected patients, with 12 weeks of treatment looking better than 8, and a higher rates of response in non-cirrhotic, treatment naive patients. Regardless, the regimen is probably not going to be used much in the post SOF/LDV era, or the one about to start (see next study), unless there is a big reduction in cost. [TULBPE10 and TULBPE11]

- In the C-EDGE study, HIV/HCV (genotypes 1, 4, and 6) co-infected patients were treated with the one-tablet regimen of grazoprevir (protease inhibitor)/elbasvir (NS5A inhibitor), with 96% cured. Five virologic failures (all relapses) out of 218 enrolled. Based on drug-drug interactions, HIV regimens were limited to TDF/FTC or ABC/3TC plus raltegravir, dolutegravir, or rilpivirine. FDA approval likely this year. [TUAB0206LB]

- In a compassionate use program in France, daclatasvir and sofosbuvir was highly effective in HIV/HCV coinfected patients with no other HCV treatment options and advanced liver disease. Treatment was 12 or 24 weeks, and RBV could be added at the discretion of the clinician. Overall cure rate 90-96% (tricky to get exact numbers given heterogeneity of treatments), with no apparent benefit of extending to 24 weeks or using ribavirin. Note that over 70% had cirrhosis. Note also that daclatasvir was just approved by the FDA for treatment of genotype 3 (along with sofosbuvir). [TUAB0207LB]

- Two studies about optimizing HIV therapy during stem cell transplants cite strategies to maintain virologic suppression. This is particularly important given the risk of severe viral rebound in these patients who have both uninfected target cells and no HIV-related immune response. Both papers cite the occasional need to use enfuvirtide — talk about a niche indication! [WEPEB337 and TUPEB298]

Finally, a little bit about the setting — Vancouver is, of course, a spectacularly beautiful city. It is much changed since 1996, with high-rise luxury office and residential buildings pretty much everywhere, and an even stronger international presence. But it’s still far from overly crowded, has those extraordinary waterfront vistas, wonderfully cool summer weather, gorgeous urban parks, great food, and the longest uninterrupted walkway in the world, the incredible Seawall.

Finally, a little bit about the setting — Vancouver is, of course, a spectacularly beautiful city. It is much changed since 1996, with high-rise luxury office and residential buildings pretty much everywhere, and an even stronger international presence. But it’s still far from overly crowded, has those extraordinary waterfront vistas, wonderfully cool summer weather, gorgeous urban parks, great food, and the longest uninterrupted walkway in the world, the incredible Seawall.

A city biker’s dream.

Now, for a tune with a Canadian theme …

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mL7n5mEmXJo&w=560&h=315]

July 18th, 2015

Disrupting the Normal Microbiota Might Make Us Fat, Allergic, Asthmatic, and Lead to Celiac Disease

Over at Open Forum Infectious Diseases, I recently had the opportunity to interview Dr. Martin Blaser, Professor of Medicine and Microbiology at New York University. He’s also the Director of the Human Microbiome Project, and author of the book, Missing Microbes: How the overuse of antibiotics is fueling our modern plagues.

Over at Open Forum Infectious Diseases, I recently had the opportunity to interview Dr. Martin Blaser, Professor of Medicine and Microbiology at New York University. He’s also the Director of the Human Microbiome Project, and author of the book, Missing Microbes: How the overuse of antibiotics is fueling our modern plagues.

Marty has been a long-time champion of the concept that our normal bacterial flora strongly influence our health. (He prefers the term “microbiota”, for the record.) He makes a compelling case that the overuse of antibiotics over the years has contributed to several modern health epidemics, including obesity, allergic diseases, asthma, and celiac disease, along with some cancers. [Edit: And now juvenile idiopathic arthritis? The list keeps growing!]

The implications of the research he cites are far reaching, suggesting that the downside of antibiotic overuse could extend way beyond selection of resistant organisms.

Full interview here, transcript here.

Highly recommended!

July 11th, 2015

Citing WHO Guidelines, Squirrels Protest Latest Virus Discovery

An open letter to the Editor-in-Chief of the New England Journal of Medicine

An open letter to the Editor-in-Chief of the New England Journal of Medicine

Saturday, July 11, 2015

Dear Dr. Drazen:

On behalf of the International Association of Variegated Squirrels, I am writing to protest the article that appeared in your July 9 2015 issue, entitled “A variegated squirrel bornavirus associated with fatal human encephalitis.”

We variegated squirrels believe the title and content of this paper are stigmatizing to variegated squirrels, and are not in keeping with recent guidance from the WHO regarding best-practices in naming new diseases.

As a reminder, variegated squirrels the world over are trying to counter literally centuries of discrimination and injustice. Indeed, the paper you published includes these chilling sentences:

All three patients [with encephalitis] were breeders of variegated squirrels (S. variegatoides). They were friends, had met privately on a regular basis, and had exchanged their squirrel breeding pairs on multiple occasions.

In our opinion, this involuntary captivity and heartless exchange of fellow variegated squirrels highlights the ongoing challenges we face on a day-to-day basis.

In addition, based on extensive communications I have had with non-variegated squirrels, I am concerned that the paper will have a similarly negative effect on all 200 squirrel species. From the five-inch African pygmy squirrel to the three-foot Indian giant squirrel, all are upset about this stigma by association. And you don’t want to get a three-foot squirrel mad at you, trust me on that one.

Squirrels — variegated and non-variegated alike — have much to be proud of. Before scientists go and name a scary viruses after us, please keep in mind the literally millions of innocent fellow squirrels who roam free, climb trees, nibble acorns and other nuts, and have never transmitted a disease to anyone.

Respectfully,

Rocky

Chairman and Spokes-Squirrel

International Association of Variegated Squirrels

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1EnDwkclDcA&w=420&h=315]

(H/T to Rebeca Plank for the photo and link to squirrel facts.)

July 7th, 2015

For HIV in the USA, Not in Care Exceeds the Undiagnosed — Solutions Welcome

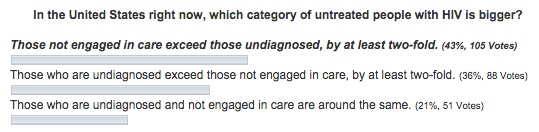

In last week’s post, I asked about two of the key components of the HIV care cascade — the “undiagnosed” vs the “diagnosed but not in care,” and which group was larger in the USA. Here are your answers as of now:

The people who read this site are a pretty knowledgeable group when it comes to issues related to HIV. This is not a blog about collecting beer steins, philosophical ruminations over baseball cards, or knitting, to cite three mentioned to me by patients over the years.

(That middle one is quite something. As is his book, if you’re into that kind of thing. Which I am.)

But more than half (57%) of even this erudite readership got the question wrong — because in the United States, those diagnosed but not in regular care greatly exceed the undiagnosed. It’s by a factor of more than two-fold to one, at least if you believe the CDC data displayed in this nifty video.

In the undiagnosed, there’s been progress: making HIV testing easier has resulted in a great reduction in those who have HIV but don’t know it. The latest data from CDC have just been published, and we’re down to just 14%. Yes, 14% is still too high — and it’s up to 25% undiagnosed in certain regions (we’re looking at you Louisiana) — but it’s a vast improvement over the 30-40% estimates we were seeing 10 years ago.

And in many regions, it’s now < 10%. Meaning that more than 90% of those with HIV know that they have it, and can get on treatment, prolong their lives, and stop spreading the virus to others.

Now, about that much bigger other group — 30-40% or so of those with HIV in the USA — who know they have HIV and aren’t getting care and treatment.

What’s up with that?

Solutions to this problem eagerly awaited.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CWf5LBfZVGQ&w=560&h=315]

July 1st, 2015

Undiagnosed or Not in Care? For HIV, Which Is the Bigger Problem?

These days, it’s hard to have a “closed book” examination.

These days, it’s hard to have a “closed book” examination.

The information is everywhere — on your computer, your phone, your tablet — whatever screen happens to be glowing in front of you.

“In the age of the internet, why be wrong?” is something my son used to say as we sat at the dinner table, grappling to remember who was the mother of Perseus, the flight time between Boston and Ft. Lauderdale, or the new name for Haemophilus aphrophilus.

(Still can’t get over that one. And yes, ID doctors have fascinating dinner table conversations.)

So it’s tough to ask you to try and take this quiz without heading over to the CDC and finding the answer. But give it a go because 1) I have a theory, triggered by a patient with advanced HIV disease I just saw in the hospital — which somehow always feels like a failure of our healthcare system — and 2) if you get it wrong, who cares? Nobody will know.

The question is about how we can possibly still have untreated people with HIV in this country, even though the medications are widely available, highly safe and effective, and simple to take. Plus, there are numerous programs in place to ensure that pretty much everyone who needs it can get coverage for treatment.

Is it that they are undiagnosed and hence don’t know that they should be on treatment? Or do they know that they have HIV, but for some reason aren’t engaged in regular care?

June 24th, 2015

Epidemic of Republican Presidential Candidates Shows No Signs of Abating

Chilling news from The Borowitz Report:

The number of official candidates for the 2016 Republican Presidential nomination has risen to thirteen, according to officials at the Centers for Disease Control…

“It might have been misplaced optimism on our part, but we had started to believe that this thing had been contained,” said the C.D.C. spokesman Dr. Harland Dorrinson. “Regrettably, it has not.”

While scientists disagree about how running for President spreads from person to person, most epidemiologists believe that a candidacy needs an environment rich in narcissism and delusion—plus a host to feed on, ideally a sociopathic billionaire.

When I contacted the author regarding this disturbing information, he responded:

You were my target audience for this one.

Does this mean he makes up the news on his site?

I’m shocked to hear that.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DR01liZXlNE&w=560&h=315]

June 20th, 2015

Alex Rodriguez’ Story Reminds Me of a Case of Scientific Misconduct — Until It Doesn’t

If you’ll forgive me a bit of baseball-related rambling, there’s an incredible story going on this year with the resuscitation of Alex Rodriguez, both as a player and, even more remarkably, as a person in the public eye.

Or, to quote the play-by-play announcer Michael Kay, who on Friday got it perfectly when he commented on A-Rod’s 3000th hit (it was a home run):

In the space of about a year, he’s gone from persona non grata to the Man of the Hour.

To quickly recap A-Rod’s “crimes,” these included the use of steroids to boost performance, lying about it when caught, and then attacking his employers in court in a pointless effort to get his full-year suspension dropped. All that behavior led to the “persona non grata” part of the A-Rod story.

And while there are still some baseball fans who hate the guy (especially around this neck of the woods, see this play for a prime example why), there’s no doubt he’s been cheered plenty this year — cheered perhaps more than any time since the sensational start to his career as a brilliant young shortstop for the Seattle Mariners.

First, he’s having an excellent season, and second (and in some ways even more remarkably), he seems to have undergone a personality transplant. His previously awkward manner now comes across convincingly like sincere humility. Whatever genius is acting as his media coach — or seeing him for psychotherapy — should win a Nobel Prize in … something.

In short, A-Rod has remade his baseball career and, at least partially, his reputation.

Which got me wondering — would we be so forgiving for such behavior in academic medicine? Scientific misconduct, in particular fabrication of research data, has several parallels.

In both settings, the guilty parties start with genuine talent, widely recognized and praised. Soon after start the short cuts to success. And in both, after an initial period of denial, rationalization (“everyone is doing it”), and self-justification (“I am so gifted/brilliant that this is what I would have accomplished/found anyway”), the evidence of guilt becomes overwhelming. This is followed by swift public censure and various degrees of punishment.

The parallels end, of course, with the postscript. A-Rod is getting another chance by many because, well, it’s just a game. And we love comeback stories in sports.

In scientific misconduct — especially the egregious cases — the stakes are too high.

Forgiveness is just not part of the story.

And apologies to one of my readers from Germany, who told me he never gets it when I write about baseball.

June 11th, 2015

Summer Is Almost Here ID Link-o-Rama

I know, I know. You’re sick of hearing Bostonians complain about the winter we just had. But did you know that the weather here didn’t get reliably warm here until, well, this week?

We all have PTSD. Don’t talk to us about anything even vaguely white, flakey, and cold. Yes, we’re afraid of refrigerated coconut.

I’ll stop whining now.

- The spread of MERS in Korea is facilitated by severe overcrowding in hospitals. Who knew that getting a hospital room in Seoul was like trying to get a reservation at a top restaurant in New York City.

- Remarkable paper on survival after AIDS-related opportunistic infections in San Francisco since the beginning of the epidemic. Vast improvement over time, of course, but not uniformly among all OIs — outcomes for lymphoma (especially CNS) and PML are still dismal.

- A short-course of antibiotics (4 days) for abdominal infections seems to be just fine. The challenge, of course, is not with straightforward cases — it’s the ones where “source control” can’t be verified. Or, to quote the fine accompanying editorial, “Early in the 21st century, it seems likely that source control remains a considerable problem in treating abdominal sepsis.” Indeed. So though it’s an important study, I don’t think we’re quite ready to remove this from the unanswerable questions list.

- Like something out of science fiction, this test can tell you every virus you’ve ever been exposed to. Based on personal domestic experience, I would bet pediatricians break all kinds of records for positivity on this one. And how long before you can get this test done at your local CVS? Further discussion here in the New York Times, in case Science isn’t your cup of tea.

- The Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines have been updated, a heroic effort that will be cited and referred to many, many times. It’s a vast document, so use the above CDC link (which has a Table of Contents) rather than the MMWR one, which doesn’t. Apps coming soon per lead author Kim Workowski.

- Provocative piece on the complex issue of academic-industry relationships, which raises the distinct possibility that anti-industry sentiment might have gone too far in medical research and publishing — a view echoed here by the Editor-in-Chief of the NEJM. Getting this issue reviewed from a different perspective is most welcome, as I can’t imagine how we could have made HIV treatable without this collaboration. Not surprisingly, these views have engendered some controversy, including from former editors.

- Related topic — here’s a fascinating profile of nucleoside-nucleotide guru Raymond Schinazi, the man responsible (to at least some degree) for several groundbreaking HIV and HCV therapeutics. This is not your typical PhD academic scientist — how many have earnings that rival hedge fund managers, George Clooney, or Alex Rodriguez? And who is more deserving?

- Shigella with resistance to azithromycin and quinolones, and widespread resistance of salmonella to quinolones. The news on these enteric bugs keeps getting worse. Thoroughly cook those burgers this weekend!

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZPlfuJYViE&w=560&h=315]

June 4th, 2015

A Slightly Less Painful Way to Learn the Three-Letter Abbreviations for HIV Meds

One of the stupid things about being an HIV/ID specialist is the highly arcane code we use to abbreviate HIV treatments.

One of the stupid things about being an HIV/ID specialist is the highly arcane code we use to abbreviate HIV treatments.

Why was zidovudine originally AZT, and now ZDV?

Why is lamivudine 3TC?

And tenofovir TDF?

Of course there are legitimate biochemical reasons why these are the right abbreviations, but they are lost to most of us who do not have degrees in medicinal chemistry.

Which is why I would like to share that someone I know — a highly brilliant researcher with dozens of papers in high-profile journals, innumerable grants and awards, and many successful mentored investigators — can’t keep these abbreviations straight.

Example: He recently shortened rilpivirine to RLP.

Sorry, “RLP” isn’t going to cut it. It’s imaginative, and original (I’d wager no one has ever used it before), and starts with the right letter, but someone of his stature would certainly be expected to know that it should be RPV.

Of course, he’s not the only one who has trouble with these tricky abbreviations. Medical students and residents despair at learning them, and ID fellows struggle as if they were learning the coagulation cascade. I recently had one smart and experienced PharmD tell me they were “alphabet soup”, and that the abbreviations for HIV meds always threaten to make any lecture on treatment deadly boring.

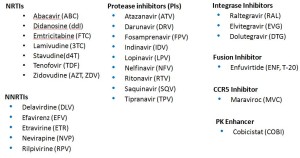

With that in mind, here’s some help. In an effort to help struggling Newbies and Full Professors alike learn these key abbreviations, I’ve pasted below three lists — Advanced, Essential, and Basic HIV Medication Lists.

First, Advanced — the whole kit and caboodle, all 27 medications (click to enlarge):

The secret here is that many of these medications are of historical interest only. You don’t really need to know the lousy old meds that are barely ever used anymore — am thinking of you ddI, d4T, SQV, IDV, DLV…

Sure, many HIV/ID specialists pride themselves on knowing all of them — and even more, that they know the years of FDA approval (of the original drug and coformulations), and the trade names. Most will even know the meds that are no longer available — for example, that ddC was the abbreviation for zalcitibine, a horrible NRTI that had the even more horrible brand name Hivid. Good grief, what were they thinking?

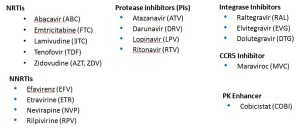

Second, the Essential list — the ones that I’d say are critical to know for most HIV/ID specialists. Note that even though several of these drugs are rarely used any longer as initial therapy (e.g., nevirapine, lopinavir), many patients still are on them and doing great — so you’ll still come across these in practice now and again:

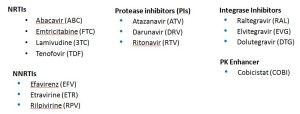

With that second list, we’re down to a mere 18 meds. But it can get even simpler, with the Basic list:

Ah, that’s better — now we’re down to just 14 — the antiretrovirals you’re most likely to encounter actually received by a patient in 2015. One might quibble and say that exclusion of lopinavir and maraviroc was unjust, but hey — we’re talking basic here! Learn these first.

Take it away, Trip.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uQnDqULwPv4]