An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

May 30th, 2016

The Sanford Guide — 46 Editions Later, Still Going Strong

I recently had a chance to visit Portland, Oregon, which for many will conjure up images of bicycles, hipsters, Mount Hood, roses, organic everything, and craft beers.

I recently had a chance to visit Portland, Oregon, which for many will conjure up images of bicycles, hipsters, Mount Hood, roses, organic everything, and craft beers.

It’s also the lifelong home of Dr. David Gilbert, the lead editor of The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy, an invaluable resource well-known to almost every clinician. Dave was kind enough to act as my host one afternoon last week, and he shared with me some interesting facts about this remarkable handbook; I’ll add some of my personal experiences with the guide as well:

- Dr. Jay Sanford provided the inspiration for the guide with a Medical Grand Rounds on newer antibiotics. The demand for the typed handout accompanying the talk was so strong that Drs. Sanford and Gilbert (who authored some of the original tables) realized they might be able to distribute it more widely. Oh, and this was in 1969 — the year of the Apollo 11 moon landing, Nixon’s first term, Woodstock, and the Miracle Mets, just to orient you to the time.

- There was never really a publisher of the guide, at least not in the traditional sense. The very definition of a home-grown enterprise: Sanford happened upon a small family-owned print house in New Jersey; they agreed to take on the project at a good price, and printed the guide for 10 years until the job became too large. It’s now printed by a large national printing company, and the publisher is “Antimicrobial, Inc” — essentially the Sanford family. Not aware of any other medical text with this arrangement.

- From 1989 through 2015, 24 million print versions of the Sanford Guide were sold. Sales peaked at 1.6 million copies/year. As with essentially every published work, print sales have declined due increasing use of the electronic version.

- The biggest challenge for the Sanford Guide was creating an electronic version. The complete process took 5 years, with the first electronic version released in 2010; the guide is now the top selling medical app in the Apple App Store. Says Gilbert: “The electronic version is frankly better in many ways… it’s much easier to express recommendations in the digital format.” Progress.

- The guide is strictly independent from industry. Before regulations on pharmaceutical gifts to physicians, we ID doctors (and I imagine others) would frequently receive a Sanford Guide gratis from various companies — often in a protective plastic cover, emblazoned with that company’s logo (only to be quickly covered with strategically placed masking or duct tape). Source of these guides notwithstanding, the content is solely created by the editors, using established guidelines and best judgment. Per Gilbert, industry might contact the editors regarding decisions on individual products, generating “spirited discussions” — but that’s it.

- The guide is published in 12 languages. Chinese, Japanese, Polish, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, Georgian, Croatian, Turkish, Korean, and Vietnamese. (In case you were wondering.)

- I got my first Sanford Guide right before doing my “core” clerkship in medicine. A friend of mine, already an intern, offered this sage advice to me, a very nervous med student: “Get a copy of the Washington Manual and that little antibiotic book with Chinese letters on the front — that’s all you’ll need.”

- The Chinese characters on the front mean “hot disease.” Sanford was a consultant to the US Army, including the Medical Corp in Korea. That’s where he first saw these Mandarin Chinese characters, and confirmed with Korean physicians that this was a way of expressing “fever”.

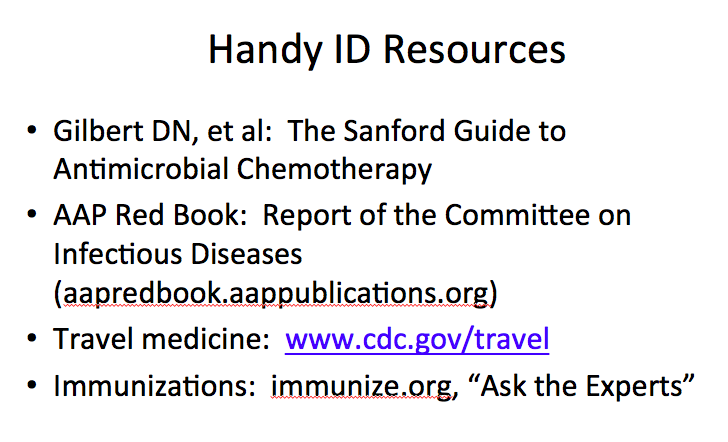

The Guide is the first of the “Handy ID Resources” I list in a talk on curbside consults. In a lecture entitled “Can I Ask You a Quick Question?” (all ID doctors will recognize that phrase), I show the slide on the right. Allows me to make a joke about the challenges of presbyopia — aren’t we doctors funny? — and to mention that the Sanford Guide comes in large print versions since the original text size became unreadable for many of us years ago.

The Guide is the first of the “Handy ID Resources” I list in a talk on curbside consults. In a lecture entitled “Can I Ask You a Quick Question?” (all ID doctors will recognize that phrase), I show the slide on the right. Allows me to make a joke about the challenges of presbyopia — aren’t we doctors funny? — and to mention that the Sanford Guide comes in large print versions since the original text size became unreadable for many of us years ago.- A friend and co-resident belittled my specialty choice of ID by citing the Sanford Guide. “How could you choose a field,” the future cardiologist asked, “where everything you need to know is in a little book small enough to fit in your pocket?” Wish I had a clever response at the time — something like, “How could you go into a field that is just an electronic pump and some tubes?” But when you think about it, there is a ton of information in each little Sanford Guide; any person who knows all its content is pretty smart indeed. (For the record, that co-resident has done quite well for himself, thank you — and I doubt he reads this blog.)

- Some ID doctors only pull out their Sanford Guide when no one is looking. I’ve had more than one ID attending — usually in his or her first year on the faculty — say they were too embarrassed to admit needing to look stuff up. The implication is that everyone should be able to remember the dose of IV ciprofloxacin with an estimated GFR of 30, or whether meropenem covers Stenotrophomonas. (It doesn’t.) But think about it — would you want your airline pilot to just try and remember the route from Chicago to Istanbul, or prefer that they consult a guide of some sort? If you need Sanford — or the Hopkins Guide, or UpToDate — no need to worry. I promise you will not be reported as deficient to IDSA, or have your board certification rescinded.

- The guide has given me numerous “teachable moments” when answering ID questions. For many years, a colleague and I answered the ID questions of a large multi-site group practice in the Boston area. Not surprisingly, the answer to many of these queries was clearly listed in the Sanford Guide. When confronted with a question on endocarditis prophylaxis, or when to give rabies shots, or whether antibiotic X covered bacteria Y, or whatever, I’d sometimes start this dialogue:

Me: Do you have one of those little antibiotic books, a Sanford Guide?

Curbsider: Yes.

Me: Now go to the index, and look up, “rabies”… you’ll find a table that tells you exactly what to do.

Curbsider: Hey, so it does! What a cool little book.

One last thing — please note that it’s the “Sanford Guide,” not the “Stanford Guide”, as newbies to medicine will sometimes wrongly say.

Those of us at the “Stanford of the East” are sensitive about this kind of mistake.

May 22nd, 2016

Drug Prior Authorizations Are a Very Blunt Tool for Cost Containment — And They’re Annoying

Insurance prior authorizations, or prior approvals (PAs) — those dreaded forms clinicians have to fill out, usually triggered by prescribing a non-formulary drug — are much on my mind these days. And most of it has to do with three letters, specifically “TAF.”

Insurance prior authorizations, or prior approvals (PAs) — those dreaded forms clinicians have to fill out, usually triggered by prescribing a non-formulary drug — are much on my mind these days. And most of it has to do with three letters, specifically “TAF.”

As readers of this site probably know, there are now three tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)-based coformulations approved for HIV treatment, all theoretically available for prescription alongside the older tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)-forms. In comparative clinical trials, TAF has consistently had a more favorable effect on bone and renal health than TDF — a benefit of considerable importance to older patients with HIV.

Why do I bring up these older patients? If you’ve been doing HIV clinical care for a while, your patient population is probably a lot like mine:

- Of a certain vintage — note I didn’t say “old”, though this apt definition isn’t far off the mark. In one of my patient sessions last week, the average age was 57 (range 45 – 71); for the record, the oldest patient with HIV seen in our practice last week was 88.

- On HIV treatment for a long time — often more than a decade.

- Virologically suppressed — they are great at taking their antivirals.

These characteristics mean that AIDS-related complications are very unlikely to happen. If I found out that one of my stable HIV patients were hospitalized after being struck by a meteorite or falling satellite, this would surprise me only a little more than if one were admitted with Pneumocystis pneumonia. If we consider the health concerns of these individuals, non-AIDS diseases are far more likely to occur than those related to HIV.

And while we clinicians can’t control the random showering of space debris, we can try to minimize drug toxicity — which brings me back to the TAF-based HIV treatments, and whether we should be using them, and in whom.

I’d argue that these older HIV patients are ideal candidates for TAF (as opposed to TDF) -based drugs, and I’ve found myself wanting to switch them from TDF to TAF multiple times each week. Aging intrinsically leads to declines in renal function and bone density, and increases the likelihood that there will be comorbid conditions further impacting the kidneys and bones (hypertension, diabetes, menopause for women). Furthermore, a patient’s lengthy HIV treatment often means that they have been on TDF for a long time — probably the most important risk factor for clinically important TDF-induced toxicity.

This clinical reasoning, however, is currently lost on most of the payers, who have set up their favorite tool — the “PA” (cue scary music here) — to discourage use of these new drugs.

As far as I can tell, it’s not that they have critically reviewed the data comparing TAF with TDF, and concluded that they disagree, or find it scientifically inaccurate. It’s simply that the TAF treatments are new, and new means you have to jump through hoops to get it.

Or, even worse, you can’t get it at all. Here’s an email I received from a pharmacist trying to help me on one of these cases, this for a 70-year-old man with osteopenia currently on TDF/FTC in whom I thought TAF/FTC would be a safer choice:

The medication is not covered and is excluded from coverage because it is a new drug to market. [Insert payer or pharmacy management company here] said that a review for coverage is not possible and that an appeal would be denied outright. They also said that a letter of medical necessity would not help to obtain coverage, either.

Thank you! Have a nice day!

Dan

Glad he can be so cheerful!

Look, I get it — drug costs are high, and PAs theoretically are a way of avoiding inappropriate use of new, more costly agents when older drugs would do the job just as well.

And though all three of the TAF formulations are cost-neutral to the older TDF treatments based on Average Wholesale Price, one has to assume there have been negotiations on price between the payers and manufacturers with TDF, deals that haven’t yet been made with TAF. (Or made public to us or our patients — “transparent” is never the word used to describe these deals.)

In addition, payers may well be looking forward to generic TDF, which is scheduled to become available next year and presumably would cost even less. It presumably will be easier to switch patients to generic TDF from branded TDF than from TAF, as a TAF to TDF switch could be viewed as switching to a potentially more toxic drug. Who would do that?

But are these mandatory PAs really the right way to decide whether a treatment is indicated — based solely on whether it’s new, and whether the clinician and his/her team have the endurance to fill them all out? Colleagues of mine delve deeper into the TAF vs TDF cost issues here, a welcome review of the relative values of these two drugs.

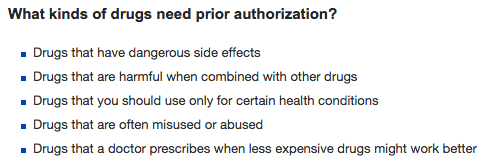

Meanwhile, over on an insurance company’s web page, they list the reasons behind PAs as follows:

As far as I can tell, bullet #5 is by far the most common reason for a PA — especially if the drug is new.

May 16th, 2016

Lots of College Graduations ID Link-O-Rama

For those of us living and working in Boston, we are most definitely smack dab in the middle of college graduation season — which means traffic is crazy, restaurants are booked, and energetic young adults are everywhere wearing gowns and funny hats.

In other words, a good excuse for an ID Link-o-Rama:

- FDA advises against use of fluoroquinolones for uncomplicated infections. Specifically, this means sinusitis, bronchitis, and uncomplicated urinary tract infections — in other words, conditions that often would get better without any treatment at all. FDA was in a tough position with this one. On the one hand, you have the fact that all antibiotics have side eff

ects — are quinolones really worse? On the other, you have personal reports like this. And not just a few of them. And, in case you’re wondering, this FDA statement is huge — very likely to be practice-changing, and something that has been in the works for years. Hope we see studies one day that give an estimate of incidence and mechanism.

ects — are quinolones really worse? On the other, you have personal reports like this. And not just a few of them. And, in case you’re wondering, this FDA statement is huge — very likely to be practice-changing, and something that has been in the works for years. Hope we see studies one day that give an estimate of incidence and mechanism. - Guidelines for evaluation and treatment of (non-Lyme) tick-borne infections updated. So what’s the best treatment for anaplasmosis, ehrlichiosis, and Rocky Mountain Spotted fever when your patient has a (maybe) contraindication to doxycycline — for example, the patient is younger than 8 years? Answer: Doxycycline! And what about the alternatives? Didn’t you hear me? DOXYCYCLINE! There are alternatives, just none of them — chloramphenicol, rifampin, quinolones — very good.

- Some smart people have known about Zika for years. I had the opportunity to interview Duane Gubler, a specialist in vector-borne infectious diseases, about Zika — and in his self-effacing way, he let on that he’s known about it for much longer than any of us. Great perspectives also on what it will take to contain it in the USA and globally, and an important side comment on Yellow Fever. Here’s a massive and comprehensive review on Zika on which he was senior author, if you can’t get enough.

- Clinical differences between Zika, dengue, and chikungunya summarized. Here’s a handy table we should all commit to memory.

- The HIV “care cascade” in the USA isn’t nearly as terrible as we thought. Specifically: 86% diagnosed, 72% retained in care, 68% on antiretroviral therapy, and 55% virally suppressed as of 2011, and it’s probably even better now. Of course, these updated data are much less newsworthy than the previous discouraging estimates — how long before these updated data are cited in place of these now famous (and much more attention-grabbing) figures?

- Deaths from opioid overdoses now exceed those from car accidents — by a lot. After a weekend of rounding on several patients with life-threatening infections from injection drug use, I wonder: Are these horrible infections counted among the casualties? For the record, I have never seen so many serious IDU-related bacterial infections, in particular among “kids” (ages 18-29).

- Over-the-counter loperamide is increasingly being used by people addicted to opioids. All of us HIV specialists have had patients on these drugs for years at a time, mostly (we thought) to counteract the toxic effects of certain antiretroviral agents. Now it appears that there is an important “off label” reason for the chronic use. Watch for the same issue with diphenoxylate/atropine (Lomotil).

- Are workforce limitations holding back treatment of HCV? As stated nicely in this editorial, “managing HCV remains entrenched in the domain of hepatologists, gastroenterologists, and infectious diseases specialists located primarily in urban referral centers.” Given the simplicity, efficacy, and safety of HCV treatment, the authors argue for expansion of treatment to non-specialists and non-MDs. Makes sense — but until that happens, keep sending HCV cases to us ID docs, we love treating HCV!

- Elvitegravir as a single-agent will no longer be available as of February 2017. (Information came as a “Dear Doctor” letter, so no link … somehow it snuck onto this “Link-o-Rama”!) Not surprisingly, hardly anyone is on elvitegravir (fewer than 50 patients nationally), which means that 99.9999% (that’s an estimate) of elvitegravir use is in coformulations, which will of course still be available. While stopping sales of elvitegravir alone is understandable based on the low utilization, even better would be removal of older toxic antiretroviral agents, such as didanosine, which can cause life-threatening side effects. I bet there are more than 50 people nationally on that drug!

- British red squirrels are getting leprosy. For years the red squirrels have been in decline due to the brash American gray squirrels, and now this! The horror. Remember, the English take their animals very seriously — some have said that this is where they channel all those warm emotions that they are so reluctant to use with people.

To wrap up in a totally different direction, some of my best friends and colleagues love musicals — me, not so much (would prefer good seats at a baseball game, thank you).

Regardless, I did think The Lion King was pretty spectacular, so enjoy!

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M-_Nm0-ZV20]

(H/T to Rochelle Walensky and Raphy Landovitz for the video, Reuters for the squirrel pic.)

May 8th, 2016

Zika, Baseball, and Waiting for a “New Normal”

I received an email from someone who’s known me a very long time.

I received an email from someone who’s known me a very long time.

Hint: She’s known me longer than anyone. Literally.

Here’s the email:

Baseball cancelled in Puerto Rico because of Zika. This story has you written all over it. (To use a cliche.)

Mom

I told you she knew me well!

For those not obsessed with this silly game to the same degree as I, here’s the story: Two games between the Pittsburgh Pirates and Miami Marlins were scheduled in San Juan, Puerto Rico on May 30-31 instead of in Miami.

This two-game series, of course, was planned before anyone had any idea that Zika would arrive and become a major health threat in Brazil, then move rapidly through Latin America and the Caribbean — including to Puerto Rico. Several hundred cases of Zika have been reported Puerto Rico (including one death), and some have estimated that 25% of the population will eventually become infected.

The players on the Pirates and Marlins raised significant concerns about traveling there, and two days ago it was announced that the series would be cancelled as a result.

Puerto Rico officials were, predictably, highly critical of the decision.

So what was Major League Baseball supposed to do? I can see both sides of this issue.

In favor of cancellation:

- A player could contract the virus and transmit it to his partner. This is of greatest concern, of course, if the woman is pregnant or trying to conceive.

- There’s still no readily available test to see if infection has occurred. A large proportion of infections are asymptomatic. Are these players supposed to wait 6 months before trying to have children? Or have unprotected sex? Seems like a lot to ask.

- There’s a small (but not zero) chance that a player will get either severe clinical Zika (fever, myalgias, and rash) or, even worse, Guillan-Barre syndrome. Bad enough for anyone — baseball player or not — but imagine if this player were a star like Andrew McCutchen or Giancarlo Stanton. (Brief aside: Stanton hit a home run nearly 500 feet the other day. Wow. Watch here.)

- What do the players get out of it? The whole idea of these trips is to promote the game globally — so it’s good for “the game”. But how about the players? They get paid the same regardless of where the games are played — why should they take this risk?

In favor of playing the games in Puerto Rico as originally scheduled:

- The CDC travel advisory on Zika is limited to women who are pregnant or trying to get pregnant. Not a single professional baseball player falls into this category. Didn’t even have to look that one up.

- The players will be mostly in settings where Zika transmission is highly unlikely. I don’t have their exact itinerary (they don’t typically share this with ID doctors), but it’s safe to assume they would stay at 5-star air conditioned hotels when they’re not playing. A comfortable air conditioned bus (at worst) would take them to and from the game. And though the stadium is old, it’s got to have an air conditioned locker room. Sure, the game itself is outdoors — but only for a few hours.

- They will only be there for three days. For such a short trip, the risk of getting Zika with the above conditions is incredibly small. Maybe almost as small as my chances of hitting a home run nearly 500 feet.

- How different is San Juan from Miami anyway? Virtually all public health officials are predicting Zika transmission in Southern Florida any day now. It might even be happening now — who knows about late May?

- Puerto Rico is the birthplace of several baseball superstars. Plenty of Hall of Famers and near Hall of Famers: Roberto Clemente. Roberto Alomar. (Hey — second time I’m writing about him!) Edgar Martinez. Ivan Rodriguez. Bernie Williams. This is an important pipeline for top baseball talent, we should support it.

- Zika didn’t stop hundreds of baseball scouts and other officials from recently visiting Puerto Rico to see a top prospect. The guy’s name, for the record, is Delvin Perez, a high school shortstop. I’d bet good money he never expected to see his name on this blog.

- They aren’t cancelling the Olympics in Brazil. If thousands of athletes from around the world can go to Rio, why can’t a couple of baseball teams go to Puerto Rico?

- Given what they’re being paid, the players should just do what they are told. The current average MLB salary is over 4 million dollars per year. The aforementioned Stanton has a 13-year, $325 million dollar contract. That will buy you plenty of DEET.

I don’t know whether baseball made the right decision on this one. But I do know that Zika is still so new, and so much is still unknown, that the decision is certainly understandable. With new threats of any sort — infectious or not — our risk assessment instincts are flawed, and typically biased toward fearing the worst.

So let’s give it a few years — Zika isn’t going anywhere, unfortunately. At that point we’ll know a lot more about how it causes disease, and in whom, and maybe even how to prevent it. We’ll certainly have better testing. There will be a “new normal” attitude about a world with Zika, just as there is now with West Nile virus, another mosquito borne virus which didn’t even exist in the Western hemisphere before 1999.

Once that new normal happens, I boldly predict that there will be professional baseball games played in San Juan.

Happy Mother’s Day!

April 30th, 2016

A Ridiculously Long Post: How EHRs Expose Unspoken Hierarchies Within Medicine — Or Maybe Are Just Bad

I am consulted by a surgeon about a patient with something that might be infectious, might not. A very appropriate referral.

I am consulted by a surgeon about a patient with something that might be infectious, might not. A very appropriate referral.

After seeing the patient and reviewing the history and scans, I decide a CT-guided biopsy is the next step.

The nice radiology fellow tells me “Just place the order in [enter name of EHR here]”. Since this is the first time I’m ordering this test using our new system, the prospect of doing so doesn’t exactly fill me with joy.

Nonetheless, I give it a go. I place the word “biopsy” in the dreaded order search box, hit enter, and cover my eyes, at least metaphorically.

A lengthy list appears, and I select the test closest to the one desired — for some reason it’s called “CT IR MASS ASPIRATION/BIOPSY (NO CATHETER) (Order #152640784)”. The order then requires filling out numerous fields (some of them woefully tiny for anyone past the age of, ahem, failing eye accommodation), clicking several check boxes, and deciphering inscrutable warning messages.

Since the precise diagnosis on this case isn’t yet known, and a precise description of the problem doesn’t come up in the formatted search, I do what everyone does when trying to navigate these complex screens and their finicky criteria.

I fudge it (in other words, make something up). Nevermind that the fudge doesn’t really fit the case — voila, it goes through!

But most importantly, the order for the biopsy includes a free-text box, where I enter the critical micro tests desired, specifically:

- routine and anaerobic culture with gram stain

- fungal culture and smear

- AFB culture and smear

- Nocardia culture and modified acid-fast smear

Note to micro lab: Prioritize pathology and fungal culture/smear if there isn’t enough specimen.

(If that seems overly detailed, trust me — I’ve been doing this ID stuff a long time. You’ve got to give precise directions. Sometimes you might even need to go from being the ID Attending to, as my brilliantly funny colleague Libby Hohmann once put it, the “Transport Attending”. That happens when you both specify the cultures to be done and are the person making sure the specimens arrive at the lab appropriately.)

After completing the order without setting the computer aflame, I feel a little glow of satisfaction — kind of like when you get a tough clue in a crossword puzzle, correctly guess your opponent’s hand in poker, or predict in advance when the runner on first tries to steal second on a 2-1 count.

Or maybe that glow is simply the computer screen reflecting off my face? Because the satisfaction is short-lived — soon after placing the order, I receive this from the radiology fellow:

Dr. Sax, thanks for your biopsy request. In addition to the order, we require you to put in separate orders for each microbiology test before the biopsy. Could you please place these individual orders- i.e. fluid culture, AFB, fungal culture, nocardia, etc and any other micro testing you think would be relevant? These will need to be entered as “Signed and Held” orders.

Brilliant.

Thoughts, emotions, reflections on this unfortunate turn of affairs.

- Why does this make me feel so worried — and frustrated? I envision entering these individual orders as a sure-fire way of heading down a bunch of digital rabbit holes, especially since some of the orders aren’t exactly common. What are the chances that the stain for nocardia would be straightforward? The frustration is amplified of course, by the fact that I already have written exactly what is wanted in the free text box. (That will be the first — but not last — time I mention this.)

- Why do I have to write these extra orders? No doubt for some billing and/or compliance reason, something completely separate from the patient care activity. Even though the desired tests are already clearly entered in the computer (second time mentioned), if they aren’t entered in exactly the right way, in exactly the right place — and by correctly, I mean “according to the rules of this particular EHR to meet whatever criteria are set up by whatever payer” — then they can’t be done because they won’t be paid for. Joy. Note that in our last EHR (we’re on our fourth), this free text order would have been fine.

- Why doesn’t someone more expert with the EHR take what I’ve written and enter the orders? Yes, this is passing the buck, but what we want is clearly spelled out in the free text box. (Third time.) It’s highly likely that someone on this care team has the expertise with this EHR to transcribe what I wrote into compliant EHR-ese. Maybe a “Super User”? Maybe a person whose sole job is to make sure orders are compliant with the above regulations? I hereby authorize him/her to make this happen.

- Why does this feel so burdensome compared to writing orders the old way? We doctors don’t mind writing orders when the process is straightforward — hey, look at my “free text” order for the micro tests cited above. (Fourth time.) Piece of cake. I have written orders like this hundreds of times, or alternatively written this exact list in hundreds of consult notes that are then transcribed into orders by others (interns, residents, PAs, NPs). But the process of writing orders has changed — it’s become tremendously nonintuitive — and even worse, it differs dramatically between platforms. You know how good electronic calendars can take your free text that says, “Dinner next Tuesday 7pm with Consuela at El Conejo Guapo restaurant”, and bingo, the dream date at The Handsome Rabbit is entered correctly? Wouldn’t that be a nice EHR feature? Dream on.

Perhaps the most important question hasn’t even been mentioned yet, and it’s this:

Why does it bother me so much?

I know, I know. In the time I spent writing this absurdly long anecdote, I could just suck it up, enter the orders, and get on with life — a bit frustrated, yes, but ready to move on to the next challenges, such as learning how to spell (and pronounce) “Aedes albopictus” and what PCSK9 actually stands for.

But first, some additional musing on this last question — why it’s so annoying — have yielded 3 key answers:

- Concern that the right tests won’t be done despite all the effort. This is the most important issue, after all — we’re all trying to help our patients. Wouldn’t it be terrible if the critical microbiology tests were omitted based on a cumbersome physician order entry system? Even after I clearly wrote the tests in the initial order? (Fifth time.) Or taken to the extreme level (why not, I’ve written this much ) — what if some critical intervention isn’t done because the order isn’t written correctly in the computer. Imagine those CPR scenes from the TV show ER if, instead of verbal orders, George Clooney had to fire up his laptop, put on his reading glasses, and start typing.

- A fear of the endless time sink. What if some of the tests don’t show up in the initial search? What if there’s an option for separate “nocardia culture”, “nocardia stain,” and “nocardia culture and stain” — do I choose the first, second, or third one, or all three? What if they ask if it’s “lab collect” or “clinic collect”, since it’s neither? How does a “Sign and Hold” order (as specified by the radiology fellow — who emphatically is blameless in this) differ from a regular signed order? I see the edge of that rabbit hole, drawing closer …

- The process elicited an uncomfortable reinforcement of the weird hierarchies in medicine. Any chance that this patient’s surgeon is dealing with the same challenges? I asked him, and he knows the EHR can be difficult, but he told me he barely ever interacts with it — he’s got a veritable army of scribes, PAs, residents, and other support staff who enter the information for him, support staff he can justify financially based on how hospitals are paid these days. Hearing he’s exempt from these frustrations elicited the same feeling I get watching the First Class flyers board the flight early. For the vast array of doctors (and essentially 100% of nurses and PAs, let the record show), no such luck. A giant chunk of EHR-generated clerical work has been handed to us in the form of mouse clicks, drop-down menus, and (too small) text fields. And it just feels lousy.

You might be wondering, after this long screed, what I ended up doing with these orders. Someone has to enter them eventually, right?

Guess.

https://youtu.be/rK1iPNeLTAo

(Picture credit: Anne Sax)

April 24th, 2016

Why Getting Old Isn’t Always So Terrible — and Why People with HIV Can Now Get Life Insurance

Two patient-related anecdotes, then a news item.

Two patient-related anecdotes, then a news item.

Anecdote #1:

A little email exchange I had with one of my patients recently:

Hi Paul,

Wondering if you got the refill request for my meds from my mail-order pharmacy — their customer service is lousy, and I can’t tell if it’s been approved. I’d like to get this settled before the weekend as I’m going away for a few weeks to celebrate my birthday.

Roger

My response:

Hi Roger,

Yes, I got the message and efaxed them the approval. They should have it to you by the end of the week. And happy birthday!

Paul

So why is this notable? He got his HIV diagnosis in 1989, and was told by more than one person (some of them famous doctors) that he’d be dead in a few years.

After some clinical trials with AZT and other early treatments that didn’t work out so well, for the last 15 years or so he has been totally stable from the HIV perspective, virologically suppressed, with a normal CD4 cell count, and no significant side effects from his treatment.

For the record, it’s his 80th birthday he’s celebrating. Guess those early predictions about his survival were wrong.

And that some older people really can do email.

Anecdote #2:

It’s 1992, my first year as an ID attending — early on in my first “real” job.

(I put it in quotes because what are internship, residency, and fellowship if not “real” jobs? Never really understood that distinction. But you get the point.)

A primary care doctor asks me about one of her patients, an HIV positive woman in her late 30s. The patient has a low CD4 cell count, but is asymptomatic. Since there is no email then, the doctor and I have an actual conversation.

It goes something like this:

PCP: Hi Paul, do you remember Tara, whom you saw once and started on AZT and Bactrim?

Me: Sure, how’s she doing?

PCP: She’s doing OK — CD4 cell count is down to 120, but she’s feeling fine. I’m wondering what to do about her cholesterol, which is over 300! Plus her mother died of a heart attack, and she’s really worried about it. Should I start her on lovastatin?

Me (skeptically): You could … but given the prognosis of someone with a CD4 of 100, and that she’s only in her 30s… is it really going to help her? How about we switch her to ddI? I can see her to discuss this.

PCP: Sounds good. But I’ll start her on lovastatin [You kids might not remember, that was the first statin drug.] It will make both of us feel better.

Me (thinking this but not saying it): There is no way she will live long enough to benefit from cholesterol-lowering therapy.

Fast-forward to today. Tara indeed continues to feel “fine”, at least from the HIV perspective — zero HIV complications, ever. Cardiovascular disease is by far her biggest threat, as she clearly has familial hypercholesterolemia.

Not the first time I’ve been wrong. And certainly not the last, as I thought the touch screen keyboard on the iPhone was a stupid idea that would never catch on.

Now the news item, from this week’s Boston Globe:

Good news — but importantly, the company is not selling life insurance policies to people with HIV for altruistic reasons. It’s no more an act of charity than when viatical companies purchased life insurance policies from people with AIDS in the bad old days (see the ad above from a 1994 magazine).

As illustrated by the above anecdotes — and no doubt thousands of others in practices around the world — survival for patients with HIV who are on treatment is every bit as good as for people with other chronic illnesses, in many cases better.

Here’s why Hancock is making this policy change, and why other insurance companies will likely soon follow:

“It’s based almost entirely on data, such as survival rates for people who have been on certain types of medication,” said Steven Weisbart, senior vice president and chief economist for the Insurance Information Institute, a New York-based trade group … “This is a very competitive business,” he said, “and companies like the Hancock and the Pru are looking for new policyholders who will buy life insurance that’s hopefully been priced appropriately.”

“What a drag it is getting old,” said the Rolling Stones, famously, in this song.

But as our long term survivors will tell us, it sure beats the alternative.

Happy Passover!

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=baQfqoZrEvI]

April 15th, 2016

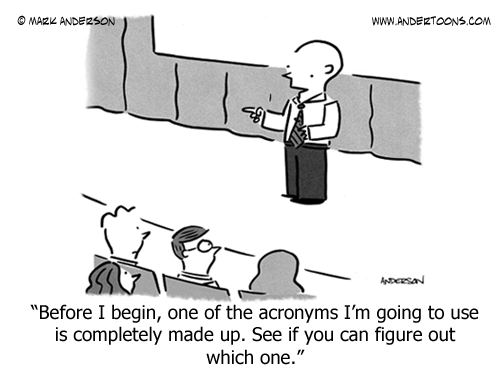

Mystifying Abbreviations on Daily Medical Rounds

I am currently attending on the inpatient medical service — always a treat, and a great learning experience for me each year. Aside from the refresher on inpatient general medicine — hey, no amount of repetition is too much when it comes to working up hyponatremia — I’m also fascinated by the steady proliferation of abbreviations and acronyms, bits of absurd sounding non-words or letters that sprout like weeds in the conversations and notes of these fine young doctors.

I am currently attending on the inpatient medical service — always a treat, and a great learning experience for me each year. Aside from the refresher on inpatient general medicine — hey, no amount of repetition is too much when it comes to working up hyponatremia — I’m also fascinated by the steady proliferation of abbreviations and acronyms, bits of absurd sounding non-words or letters that sprout like weeds in the conversations and notes of these fine young doctors.

Below a select list of some of the commonly used terms bandied about by our skillful interns and residents. Some are nationally used, others are just local-isms that are highly relevant for our hospital’s patient population.

- MOLST

- BMP — not to be confused with BNP, which also wasn’t in circulation when I was a resident (because it wasn’t available), but is now pretty established

- CIWA

- G and G — originally I thought it was GNG, but it’s not.

- CTPE

- TTP — not the hematologic disorder

- WOB

- DOAC

- HDS

- PNA

- TROPE

- RUCKUS — at least that’s how it’s spoken, as in making a lot of noise (a ruckus), but (hint) not spelled that way.

- APLAS

Note that none of these abbreviations or acronyms was in circulation when I was a house officer, but of course that was some time ago (ahem), so that’s not surprising. What’s remarkable is that many of them weren’t even used much last year, showing the remarkable fluidity of medical language, and ensuring an unending supply of confused medical students and gray-haired doctors.

So how many of them do you know? Please offer some guesses in the comments section. Upfront warning — the degree of difficulty is highly variable, and using the google machine (or even UpToDate) may not help.

April 2nd, 2016

You Too Can Have Fun with Academic Spam

Like most doctors who work at academic medical centers, I get a fair amount of “academic spam” — invitations to bogus meetings that take place in some exotic or at least warm place (China, Dubai, and Orlando are favorites), efforts to sell me monoclonal antibodies or, more recently, CRISPR-altered mice, and of course requests to contribute research papers or review articles to made-up journals.

These efforts must make money because, well, otherwise they wouldn’t exist.

So here’s a wonderful opportunity that recently came my way (some details changed to protect the “innocent”, but assuredly I haven’t changed the writing style or font colors one bit):

Editorial Board Membership: Wilkie Renal DisordersDear Dr. Paul E,Greetings of the day!It is an excited endeavor to start a new open access journal in the field of Medicine. At the onset, we would like to invite you to join us as an Honourable Editorial Board Member of Wilkie Renal Disorders.Wilkie Renal Disorders is an open access, peer reviewed, scholarly journal dedicated to publishing articles in all areas. The aim of the journal is to provide a forum for Nephrologists, researchers, physicians, and other health professionals to find most recent advances in the areas of clinical and experimental renal disorders.Please visit our journal at: http://wilkiepublishinggroup.com/wilkie-renal-disorders/If you are interested, kindly provide your short CV full contact details along with expertise keywords of your ongoing research work.We await your reply with interest.Best regards,Samantha FarnsworthEditorial office- Wilkie Renal Disorders# 54 Turniptown Way,

NEW JERSEY 08831, USA

Tel: +1-201-698-7575

You can imagine how excited I was to receive this invitation. Quickly, I replied as follows:

Dear Samantha:

Greetings of the day back to you! I’d be honoured to accept your invitation to be on the Honourable Editorial Board of “Wilkie Renal Disorders”. Here are my demands, which an impressive journal like yours no doubt will find easy to fulfill:

That you provide me board certification in nephrology, as I am currently trained only in bloodletting and bicycle repair.

That you provide me board certification in nephrology, as I am currently trained only in bloodletting and bicycle repair.- That you continue to refer to me as “Dr. Paul E.” The “Sax” part was always tricky for people to spell, and took too long to write.

- That during Editorial Board meetings, you allow me to bring my companion pet lizard, a green iguana whose name is Oscar. He’d appreciate a name tag during the meetings so that he feels like part of the team! Attached please find a photo so you’ll recognize him when he comes.

I look forward to a long and productive working relationship!

Regards,

Paul E.

Haven’t heard back yet. Maybe they have a “no iguanas” policy for their renal journal.

But the good news is that the next day the same publishing company invited me to be on the board of their Orthopedics journal, which I hear is much more liberal with companion pets.

March 27th, 2016

One-Week-to-Baseball ID Link-o-Rama

(Important note: Title has nothing to do with this post’s content. I just felt like writing something about baseball.)

As some of us eagerly await the start of the 2016 baseball season — especially Cubs fans — here are some ID/HIV items yearning to shag flies, toss around the horsehide, and play some pepper:

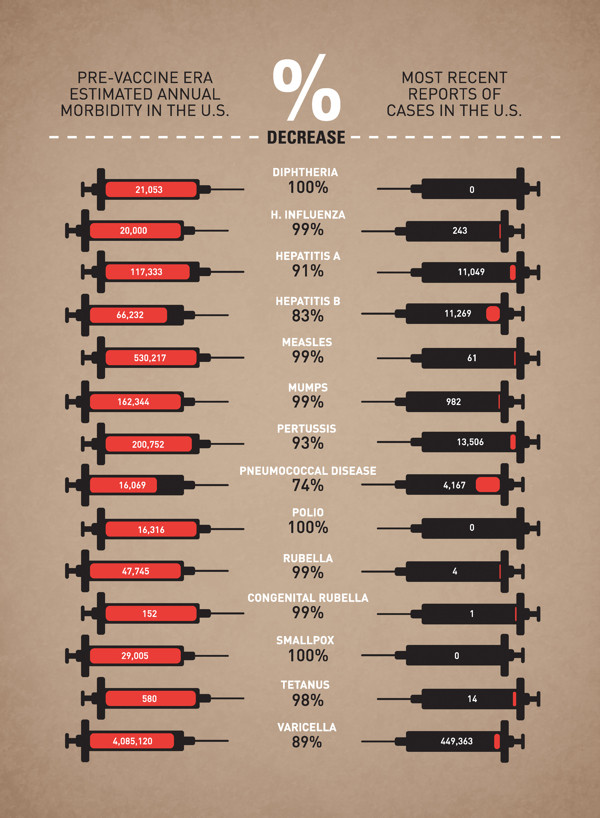

- Famous anti-vaxxer — and notorious scientific fraud — Andrew Wakefield was going to have his film shown at the Tribeca Film Festival, but now it’s been pulled. Robert De Niro might be a great actor, but he whiffed big time on this one. Here’s a humorous editing of the festival’s original biography of the filmmaker (notice I don’t write “scientist” or “doctor”).

- TB cases in the USA are up for the first time in 23 years. Up a little — 157 more cases in 2015 than 2014. It’s the end of a longstanding decline, a remarkable success story (so far). The CDC report accurately describes this as a “leveling” of TB rates — it’s not a “surge” as the headlines in the popular press write — but it also makes the complete elimination of TB in this country increasingly unlikely.

- CRISPR/Cas9 eliminates HIV from T-cells. With the caveat and confession that I’ve never done a single second of basic science research, my gut feeling is that this (or a related strategy) is more likely to be successful at curing HIV than giving chemotherapy-like drugs to “awaken” the latent reservoir. But what do I know? Good review of CRISPR for non-lab scientists here.

- While we’re curing HIV, let’s also try a new HIV vaccine strategy. This one will generate broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs), which are all the rage.

- Lots of flu out there right now. You’d almost think influenza is seasonal, or something crazy like that.

- The outbreak of Elizabethkingia anophelis in Wisconsin continues to baffle public health officials. The bugs are genetically related, but there’s no obvious environmental source (yet), and cases are widely dispersed geographically. Contaminated injectable medications, or an intravascular medical device, both distributed from the same (unsterile) point of origin? Trivia question — what was Elizabethkingia called before it was named after microbiologist Elizabeth O. King?

- CDC has issued an updated guidance on caring for women and men of childbearing age with Zika exposure or disease. Key take home recommendations: After symptomatic disease, women should wait at least 8 weeks before attempting conception, and men at least 6 months. With possible exposure and no symptoms, both should wait at least 8 weeks. As the data linking Zika to birth defects continues to accumulate, these guidelines make a lot of sense.

- In other mosquito-related infection news, this dengue vaccine candidate (TV003) looks very promising. All 21 vaccine recipients were protected against infection after challenge with a weakened form of dengue; by contrast 20 out of 20 placebo recipients developed viremia, 80% a rash. Importantly, TV003 elicits antibodies to all 4 dengue serotypes. At least two large clinical trials are being conducted, one in Brazil, one in Thailand.

- In this observational study, antibiotic exposure in babies was not associated with childhood obesity. It’s just one negative study; nonetheless, it would fascinating to get an interpretation from Marty “Missing Microbes” Blaser, who writes and speaks quite eloquently on this putative link between antibiotic overuse and the obesity epidemic.

- Here’s the study showing that dolutegravir significantly increases metformin exposures. These data led to a dolutegravir label change a few months ago, stating that metformin dosing should not exceed 1000 mg a day in patients taking both drugs. Dolutegravir and raltegravir have so few significant drug interactions, it’s critical to remember the important ones.

- Toxoplasmosis is associated with impulsive behavior and aggression. I gather toxo does the same thing to mice, making them more reckless — and hence more likely to be nabbed by cats (the source of the toxo to begin with). These studies on the neuropsychiatric effects of this parasitic infection in immunocompetent humans periodically appear in the medical literature; recent review here.

- Good targeted review of rapid TB diagnostics, in particular their use in low-prevalence settings. We’ve got a lot to learn from the extensive use of Xpert globally.

- Speaking of, the giant-pouched African rat can diagnose tuberculosis. It’s multi-talented, as it also can find land mines — here’s their web site. Maybe it’s just me, but I find the UTI-detecting dogs much cuter.

In case De Niro wants a movie short to replace the one he’s now cut from the Tribeca Film Festival, he can show this one — it would be better than Dirty Grandpa.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3aNhzLUL2ys]

March 20th, 2016

“Choosing Wisely” in HIV Medicine — Should We Stop Giving MAC Prophylaxis?

(Disclosure: The following post represents personal opinion, and is in conflict with treatment guidelines. Proceed at your own risk.)

(Disclosure: The following post represents personal opinion, and is in conflict with treatment guidelines. Proceed at your own risk.)

E-mail recently from one of our outstanding first-year fellows:

Hi Paul,

I’ve heard you recommended against the use of MAC [M. avium complex] prophylaxis in most settings in the modern HAART era. We admitted a 21yo F patient, non-compliant with meds, with a CD4 of 2. She has poor tolerance of pills in general which has been a major obstacle to her care. Would you recommend against the use of MAC ppx in this patient? Even with a CD4 of 2?

Thanks.

It’s a great question, notwithstanding the use of the term “HAART”. (I think she did that just to bug me).

In general, I’m not recommending MAC prophylaxis anymore, and here’s why:

- It’s never been proven necessary in the modern ART era. For the record, this is the most relevant placebo-controlled trial, and it enrolled patients from 1992-1994—eons ago, ART-wise (only available HIV therapies were NRTIs). There’s certainly no controlled clinical trial since 1996, when effective ART became widely available. This observational study from the HIV Outpatient Study (too bad it wasn’t the MACs cohort, ha ha) didn’t find any benefit, and this one from the early ART era was conducted in 1996-1997, a time when virologic suppression rates in clinical cohorts was 20-30%. Please tell me if I’m wrong and there are other more relevant studies.

- Effective HIV therapy reduces MAC risk much more than azithromycin ever did. Disseminated MAC was, along with CMV retinitis, one of those dreaded “final common pathway” OIs that occurred late in HIV disease, almost exclusively in patients with longstanding severe immunosuppression. The incidence of both of these conditions—especially if you limit diagnoses to non-IRIS cases—has dropped dramatically.

- Some of these advanced disease patients may have undiagnosed MAC. It could be clinical or subclinical, and you wouldn’t want to give low-dose “monotherapy” to them anyway. They might develop MAC IRIS, but do we have any evidence that MAC prophylaxis prevents MAC IRIS?

- High-dose, weekly azithromycin has side effects. These are mostly GI side effects, and I’d argue anything that might make it tougher for someone with a CD4 < 50 to take ART is a bad thing.

- Any antibiotic administered chronically selects for resistance, will alter the “microbiome.” Although clinical studies of MAC prophylaxis didn’t find much macrolide resistance in M avium, resistance to macrolides among other bacteria is widespread. And one dose of an antibiotic can alter the microbiome.

- It costs money. Not a lot, but something. And if it’s not doing any good, or even worse, distracting someone from taking ART, it’s bad value.

So could there be anyone in whom I’d still recommend MAC prophylaxis? I suppose—but without much enthusiasm, and only if all the following criteria were met:

- Newly diagnosed with HIV, or newly ready to take ART.

- CD4 < 50.

- No clinical symptoms or signs consistent with MAC.

- Expresses strong commitment to taking ART now that he/she has this serious diagnosis (AIDS).

In these cases, one could argue that it’s possible that giving it would provide some benefit during this very vulnerable period. If the patient takes ART, furthermore, the CD4 will soon be above the threshold allowing discontinuation of primary MAC prophylaxis,

But I’d have a very low threshold for stopping it (any GI toxicity in particular) even before the CD4 cell count is > 100, and would make it abundantly clear that this patient’s true lifeline to health is HIV therapy.

So what about a controlled clinical trial? It’s never going to happen—the incidence of MAC is too low these days, so the sample size would need to be untenably large. Additionally, finding and enrolling patients who meet the CD4 entry criteria would be an enormous challenge. These are not the easiest patients to get into clinical trials.

So what say you, ID/HIV specialists—should we still be prescribing MAC prophylaxis?