An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

November 6th, 2016

Do ID Clinicians Perpetuate Our Own Stigma?

Infectious Diseases doctors will find this exchange familiar:

New person you’re meeting: What to do you do?

ID Doc: I’m a doctor.

New person: Oh — what kind?

ID Doc: A specialist in Infectious Diseases.

New person (making a face, or moving a few feet back, either to be humorous or truly frightened, or both): Yuck! Well I guess someone has to do it …

The stigma associated with Infectious Diseases is as much a part of the field as knowing why Pneumocystis carinii is now Pneumocystis jirovecii, and how to pronounce the drug class that includes linezolid and tedizolid. (Oxazolidinone.)

I mention this aspect of ID as it came up recently in the context of our shiny bells and whistles electronic medical record. One of its many features (common to most EMRs) is that you can generate letters to patients to notify them of their lab results.

Here’s what the header to those letters looks like; I highlighted the key problems:

There are four issues with this image, three small, one big. The three small items first:

- That’s the old hospital insignia. Here’s the new one.

- The lower-case “b” in BWH. Hello, can we get a proofreader in here?

- For some reason it’s calling our practice “bWH Infectious Diseases Medicine”, which is a term used literally nowhere else — we’re the “Division of Infectious Diseases” to the rest of the world.

None of these is a big deal (though it is kind of ironic to see what you get for your billion dollars).

What is a big deal, however, is that many of our patients have made it abundantly clear to us that they don’t want any references to “Infectious Diseases” on materials mailed to them.

Worse would be “Infectious Diseases” on the envelope return address — gosh, anyone could see that — but mentioning it at the top of a letter is also off limits. (For the record, our old EMR had an option to choose “generic BWH letterhead”, and we went with that as the default.)

We’re also not supposed to say we’re calling from “Infectious Diseases” when leaving appointment reminders or other voicemail messages. So we don’t.

And there’s more.

I’ve had patients tell me that they don’t like the fact that our practice is called “Infectious Diseases” in the hospital directory, preferring that we be listed by some generic term — one suggested we go back to the plural, “Medical Specialties”, which is what our office used to be called when we shared clinical space with Renal, Pulmonary, and GI. Another wanted the bland moniker “Brigham Associates” — to which I would always wonder, “associates with what?”.

Some don’t even like sitting in our waiting room — this is very sad, when you think about it — even though they are coming to us for their own ID problem.

But think of how we’ve responded to our patients’ concerns:

- Many ID/HIV practices or inpatient services have various euphemisms that say nothing about the mission of the clinicians — Ward 86, the Moore Clinic, the 1917 Clinic are three famous examples.

- A terrific group of HIV/ID nurses I’ve worked with for over 20 years calls themselves “The Resource Team.”

- I know a famous hospital (yes, again that other one in Boston abbreviated with 3 letters) that frequently refers to HIV as “Z virus” — a longstanding tradition that greatly precedes (and has nothing to do with) Zika.

So back to our patient letters: I contacted our excellent IT liaison to see if we could change the letterhead back to something that doesn’t say “Infectious Diseases”, and included our HIV social workers in the email thread, thinking they would certainly amplify the importance of this change to our patients.

Surprisingly, I got this back from one of them:

Does any other department need to protect their patients by disguising the name of where they work? It’s as if we own stigma like our patients. In Social Work they call that “the parallel process”. It’s kind of a part of our own identity, our reality, and for some of us our pride in our specialization. I’ve been changed as a person because of it. Wow, really getting deep this morning!

Susan

Susan has a point. Imagine if “Dana-Farber Cancer Institute” or “Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center” were asked by their patients not to include the word “Cancer” in their names. Or if a Cardiologist asked to remove his or her specialty from their hospital identification badge — I know one ID doctor who actually did this, as he didn’t want to make patients or hospital coworkers uncomfortable.

Makes you think. Are we doing more harm than good in treating our field with such exceptionalism?

October 29th, 2016

Are Antibiotics Useful for Small Skin Abscesses? Now There’s an Answer

Let’s start with the clinical controversy, one that’s been bouncing around Emergency Rooms, outpatient practices, postgraduate courses, and medical journals for years. Specifically, are antibiotics helpful for skin abscesses that are adequately drained?

It’s still debated since of course most patients with this annoying problem will get better on their own provided the drainage is adequate. What do the antibiotics add, if anything?

Now, thanks to a superb clinical trial presented this past week in New Orleans at the annual IDWeek Meeting, we have some answers.

And though the study is important, there’s a good chance you don’t know about it, even if you attended IDWeek. First, just like the last time this group presented results of a different trial on at a national meeting, the abstract presentation took place in front of a only a handful of meeting participants.

Second, even if you wanted to come see the presentation, you might have been stymied by the vast travel distances inside the New Orleans Convention Center, which must be one of the longest indoor spaces on the planet. Safe to say that no one who attended this meeting finished a day with fewer than 10,000 steps, unless they brought along their hoverboards or Segways. Sometimes it felt like I was walking half the way to Baton Rouge.

(For the record, that first study ended up being a major paper in the esteemed New England Journal of Medicine. Justice!)

Anyway, here are some of the details of this new study:

- Adults and children with small skin abscesses were eligible provided they weren’t immunocompromised, diabetic, or systemically ill.

- They all underwent abscess drainage and cultures.

- Participants were randomized 1:1:1 to receive TMP/SMX, or clindamycin, or placebo for ten days. (Glad they followed the Golden Rule.)

- 786 subjects enrolled (505 adults and 281 children) at several sites around the country.

- 67% had positive cultures for Staph aureus; 74% of these isolates were MRSA.

- At a 10-day post-therapy visit, cure of infection was seen in 83.1% and 81.7% of clindamycin and TMP/SMX treated patients respectively — both significantly better than placebo (68.9%).

- TMP/SMX was better tolerated than clindamycin, with adverse event rates of 11% (TMP/SMX) and 22% (clindamycin). Placebo was 12.5% (guess that’s the “nocebo” effect). There were no cases of C diff or severe rashes.

- Clindamycin-treated patients had fewer relapses than those receiving TMP/SMX.

The droll presenter, Dr. Robert Daum, and the senior author, Dr. Chip Chambers, made a couple of other interesting observations. First, if the culture grew a Staph aureus resistant to clindamycin, responses were reduced. The good news is that this resistance was observed in only around 5% of isolates, a much lower percentage than typically seen in Staph aureus from hospitalized patients.

Second, if cultures were negative for staph, response rates were similar between all three treatment arms — meaning you could potentially stop antibiotics in select patients based on culture results (though important caveat, this strategy wasn’t tested).

The results of this study add to a growing body of evidence that antibiotics do in fact improve outcomes even for drained skin abscesses, swinging the pendulum further back in the direction of using them for this indication. Whether you and your patient think that this net 10-15% increase chance of cure is worth the risks of antibiotics will probably depend on the case — but at least now we have the data to make an informed decision.

And boy, do my feet hurt.

October 20th, 2016

Back to School: Questions from “ID in Primary Care” — Shared and Answered!

Once again, we’re giving our “Infectious Diseases in Primary Care” post-graduate course in beautiful Boston — where the weather is perfect, the air crisp and clear, and we are all watching with excitement as the few remaining baseball teams and presidential candidates make a mad dash to the end of their respective races.

Once again, we’re giving our “Infectious Diseases in Primary Care” post-graduate course in beautiful Boston — where the weather is perfect, the air crisp and clear, and we are all watching with excitement as the few remaining baseball teams and presidential candidates make a mad dash to the end of their respective races.

(You might have heard something about that.)

As in the past, we get a boatload of excellent questions from our participants, most of whom are highly experienced primary care clinicians. Note that not all of these questions have a definitive answer, so if you have an opinion or want additional clarification, please weigh in!

Off we go:

- One of my patients had a positive tuberculin skin test, but didn’t believe it, so I sent a [insert brand name here for your interferon gamma release assay of choice, which I hate typing]. That came back as negative. The blood test is more accurate, isn’t it?

We get this one every year, so might as well start off with it! The problem here is that there is no “gold standard” for diagnosing latent tuberculosis — it’s easy when they both agree, but sometimes the TST is positive but not the IGRA, sometimes the reverse, and neither test has 100% sensitivity. The main advantage of the IGRA is that it is less prone to false-positive results from either BCG or non-tuberculous mycobacteria. In the case when you have a discordant result, go with the one that you think makes the most sense based on the likelihood of lifetime TB exposure — and don’t forget to use the invaluable Online TST/IGRA Interpreter to help guide your decision! If the stakes are particularly high (e.g., about to get TNF inhibitors), act on the positive result. Read more on this topic here. And to reiterate, typing the brand names of IGRAs is NO FUN AT ALL, but here goes: QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube and T-SPOT.TB. Good grief. - My patient doesn’t want to get the zoster vaccine since she’s afraid of getting a live-virus vaccine. Should I just wait until the inactivated vaccine comes out and then immunize her?

Sure, it’s reasonable to wait. The inactivated zoster vaccine has been tested in multiple prospective clinical trials (for example this recently published study in adults 70 or older), and is highly effective at reducing the risk of zoster, and also quite safe. Currently under FDA review, it will probably also require vetting by the American Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) before insurance plans will cover it. The current live-attenuated zoster vaccine is also safe and effective, but since zoster immunization is hardly urgent, if your patient wants to wait, that’s probably the way to go. Hey, I heard the vaccine may carry the nifty brand name “Shingrix”. I make fun of lots of brand names on this site — Fulyzaq, R.I.P. — but got to give credit when the marketers come up with a good one, and “Shingrix” is emphatically one of those. - Do we really need to get a chest X-ray on a young patient with suspected pneumonia? Why not just treat them based on physical findings?

The primary reason to get a CXR is that the optimal antibiotic choice depends on what part of the lung is involved — levofloxacin, for example, is particularly effective in the left lung. (That was a joke. Ha.) Actually, my colleague Mary Montgomery fielded this one, so I’ll let her answer: “It’s important to get a CXR in order to avoid giving unnecessary antibiotics for acute bronchitis, which gets better without them — most are viral. We used to think that any radiation exposure was worse than antibiotics, but as we are learning more about the microbiome and antibiotic resistance the risk equation is changing. The radiation risk from one CXR is equivalent to 10 days of natural background radiation. (For comparison a mammogram is equivalent to 7 weeks of natural background radiation and a PET-CT is equivalent to 8 years!) And every antibiotic dose risks changing the microbiome, causing antibiotic resistance, or leading to C diff.” - How do I choose between the multiple flu vaccines available?

Choosing among the current flu vaccine options is like trying to choose a breakfast cereal in a large US supermarket — there’s simply too much choice, and that’s without the live intranasal vaccine this year. Regular dose, high dose, trivalent, quadravalent, adjuvanted, eggless, mercury-free — pretty soon they’ll be offering them with free WiFi and a breakfast buffet. The ACIP won’t put their money down on any single vaccine brand, essentially saying “Get any of them — they all work.” Note the latest entry to this dizzying array of options — a recombinant egg-free quadravalent vaccine. I suspect the various Guidelines Committees are awaiting more definitive efficacy data, especially on the high-dose vs regular dose option — until then, we a study showing somewhat better response rate to the high-dose vaccine in the elderly. Some think this is enough to use the high-dose in the elderly, others don’t. - I heard the flu season last year didn’t peak until March — is that because we’re vaccinating people earlier in the year, and their antibody protection wears off in late winter?

While there is evidence that antibody titers decrease over time after influenza immunization, this is not the reason the season peaked in March last year. Flu season peaks change year to year, usually falling somewhere in the northern hemisphere between December and March. As to why it varies like this, only the people who can predict the severity of the upcoming flu season can tell you. (Big secret: They don’t know that either.) - I saw someone in my office recently who told me he was on a plane for 3 hours next to man who was coughing the whole time. He’s worried he might have been exposed to TB. How long should I wait before testing him?

You should test him now, to establish a baseline — especially if you don’t have a prior negative one on file. Since it takes 2-8 weeks to generate an immune response to TB after exposure — and it’s the immune response we’re measuring with both the TST and the IGRAs — guidelines suggest waiting 8-10 weeks after exposure for the second test. Remember that converting from negative to positive has a greater urgency for preventive treatment, as the risk for active disease is much greater in the first few years after acquiring TB. And while most people who are coughing a lot on planes do not have tuberculosis, I’m going to propose that airlines have the equivalent of negative air flow rooms for their coughing passengers. Can’t be too sure, right? - I take care of patients in a capitated healthcare system, and we’re grappling what to do about hepatitis C treatment. It’s just so expensive!

If you agree that curing HCV before there’s significant liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, cancer makes sense — and of course you do, it’s medically irrefutable — then we have to prescribe these treatments for our patients. The good news is that the cost is way down from the crazy “SIM-SOF” days of 2014, when curing a single patient of HCV could easily cost > $100,000. There are now numerous options for therapy, in particular for genotype 1, all of them more than 95% effective and many consisting of just one pill a day for 12 weeks. This wide range of choices has had the expected effect on pricing, with deep discounting off of “average wholesale price” now the expectation for all insured patients, whether their coverage is private or government payer. So if you haven’t looked into it for a while, you’ll likely be pleasantly surprised — estimates of current cost/cure are roughly $20-40,000/patient, depending on the regimen and the payer. Still a lot of money, but think of what we’re getting in return! - Can you please continue to put fun videos on your blog?

Gladly. Meanwhile, if you have some questions appropriate for this course, post them in the comments section below, we’ll do our best to answer. And next year’s course looks like it will be October 25-27.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K_7k3fnxPq0]

(Hat tip to Joe Posnanski for the video.)

October 9th, 2016

Why Guessing An ID/HIV Doctor’s Political Affiliation Is Easy

One of our medical school’s most beloved teachers gives a wonderful lecture on how to give an effective presentation. He offers many invaluable tips for a successful talk, such as 1) Show up early; 2) Know your audience; 3) Don’t read your slides; 4) Never include a slide that you need to preface by saying, “I know you can’t read this, but …”

One of our medical school’s most beloved teachers gives a wonderful lecture on how to give an effective presentation. He offers many invaluable tips for a successful talk, such as 1) Show up early; 2) Know your audience; 3) Don’t read your slides; 4) Never include a slide that you need to preface by saying, “I know you can’t read this, but …”

He also cites certain “off limit” topics that could alienate you from your learners, hence best avoided if possible.

Here’s the list:

- Sex

- Politics

- Religion

Wise advice.

But to an ID/HIV specialist, Topic #1 is simply unavoidable. Sorry. And since we’re less than a month from wrapping up one of the most bizarre presidential races in U.S. history, Topic #2 is front-and-center in everything we do these days, and where we’re going to venture today.

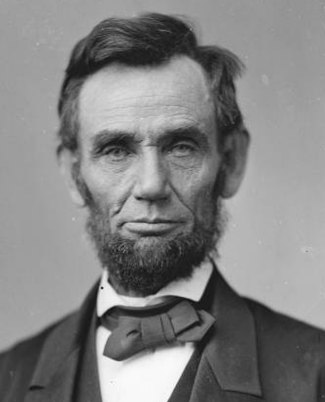

The motivation is a New York Times piece published last week entitled, “Your Surgeon Is Probably a Republican, Your Psychiatrist Probably a Democrat.”

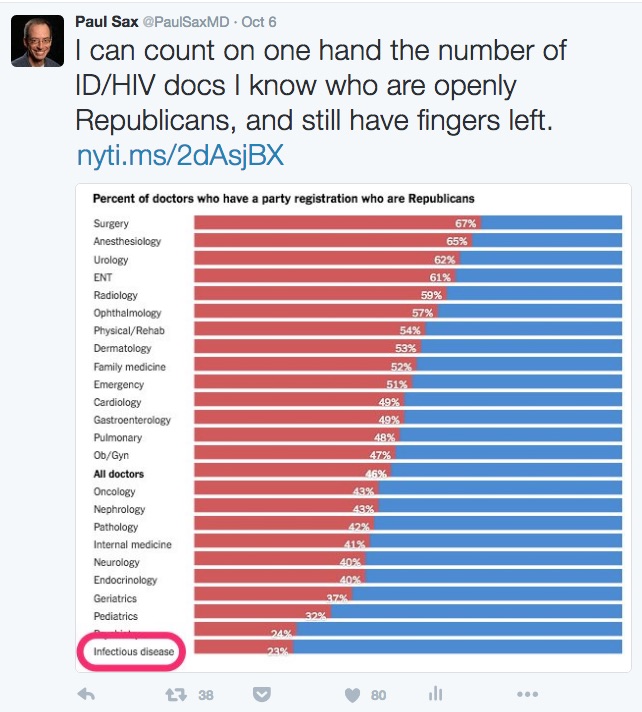

Which prompted me to offer this observation (and lightly edited figure):

So if I might edit the title, it could be, “Your Surgeon Is Probably a Republican, Your Psychiatrist Probably a Democrat, and Your ID/HIV Doctor Probably Hasn’t Voted Republican Since Lincoln.”

(Actually, that’s not quite true — but you get the idea. And it’s Psychiatry right above ID in the figure, obscured by the highlight I added.)

So now that I’m deep into these dangerous political waters, I’m wondering why we’re at the bottom of this graph. Or at the top, if you flip the question.

Two quick thoughts inspired by the article:

- ID/HIV doctors support the “safety net” culture of healthcare. Think about our AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) and Ryan White Care Act — arguably among the most successful national health programs in the country. (For the record, ADAP was the topic of the second-ever post on this site way back when, triggering all kinds of prickly comments. Glad the nice people at NEJM Journal Watch didn’t pull the plug right then and there.) And consider organizations such as Partners in Health or Médecins Sans Frontières. Or the vast number of ID doctors who devote their energies to global health, or to emerging infectious diseases, or to life-threatening outbreaks, or to diseases that disproportionately strike the poor or disenfranchised (tuberculosis, malaria, HIV, HCV, cholera, parasitic diseases), or to working in “free” clinics for sexually transmitted infections. Somehow these efforts register as more Blue than Red, don’t they?

- Money. Hey, this isn’t the first time we ID/HIV docs have been at the bottom of a figure — remember 2014, when we ranked last in salary? Things have improved for us since then, fortunately, but even with these salary gains, we’re hardly in surgical specialty territory. So there’s a strong correlation (higher salary, more likely Republican), but it’s hard to argue that this relatively low pay directly causes Democratic leanings — unless you conclude that highly paid doctors resent high taxes (which after all pay for those safety nets) more than we do.

But it’s probably more complicated than just these two factors, so would be interested in your thoughts.

And just for fun, let’s make it 3 for 3 on those prohibited topics …

October 2nd, 2016

“Brink of HIV Cure” ID Link-o-Rama

There, that title got your attention, didn’t it?

There, that title got your attention, didn’t it?

Anyway, this HIV cure news thing and a few other ID/HIV topics to contemplate while buying your pumpkin, celebrating the New Year in October, or shaking your head that all the stores seem to be putting out their Christmas stuff already. I mean, come on — it’s not even Halloween!

- Are British scientists really on the “brink” of an HIV cure? No. Very glad they are making “remarkable progress”, but sounds like overly ambitious headline-writing to me. Reminiscent of this story from a few years ago.

- Nice summary over the latest controversies involving the flu vaccine, in case your patients are asking. Repeated vaccines leading to reduced response, status of the live attenuated nasal vaccine (not dead yet — pun intended!), effect of statins (but not NSAIDs — remember that?) — lots of good stuff here. And yes, we should still be encouraging the annual shot.

- Another complication of severe influenza infection — invasive aspergillosis. Everyone knows about bacterial superinfections, now here’s another one to watch out for this flu season.

- Serious illness appears to be rare among children who acquire Zika. Refreshing to have some good news on this particular subject. Note that most of the children in this series were older (median age 14), hence it’s not known whether acquisition of Zika in a newborn would have different clinical manifestations (in particular, long-term neurologic complications).

- On the topic of Zika, CDC now recommends that men wait at least 6 months from last possible exposure (if even if asymptomatic) before attempting conception with their partner. This 6 month wait was previously recommended only for men who had symptoms. Is there a role for antibody testing after possible exposure? Unknown, but I bet good money that people will do it (understandably).

- Tenofovir alafenamide works just as well as tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for hepatitis B. As we’ve seen in other comparative studies with TDF, there was a more favorable effect on bone and renal markers. Since treatment is going to be lifelong, the rationale behind using TAF over TDF in hepatitis B is going to be just as strong as it is with HIV. (And you can use TAF in co-infected patients, despite the package inserts for TAF/FTC, ECF-TAF, and RF-TAF.)

- From 2010-2013, approximately 1 in 4 people newly diagnosed with hepatitis C already had laboratory evidence of advanced fibrosis. Suspect the situation is much better now — there’s been a huge push for screening — but these data indicate a substantial burden of HCV-related disease regardless.

- Prospective study shows that patients with HCV-related cirrhosis have significantly better outcomes after HCV cure. Important outcomes, too — lower rates of hepatic decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma, and death. People with HCV-related cirrhosis are analogous to HIV with CD4 < 200, or AIDS complications — that is, those likely to benefit the most, and soonest, from treatment.

- A single dose of azithromycin significantly reduced the risk of post-cesarean section infection when added to standard cephalosporin prophylaxis. Putative explanation is azithromycin’s activity against Ureaplasma urealyticum. Data from this study seem very convincing, and likely to change standard of care soon.

- One mother explains why she’s no longer anti-vaccine after her whole family — including her three children — developed severe rotavirus infection. Very brave to go public with something like this, and valuable, too, as turnarounds from previous anti-vaccination individuals seem particularly persuasive. For the record, my pediatrician wife says her practice saw a decline in hospitalizations only months after the rotavirus vaccine was approved.

- The HPV vaccine is already reducing the incidence of incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. It will be fascinating to see how guidelines for cervical cancer screening are modified (with presumably reduced need for screening) as the cohort of vaccinated females ages.

Meanwhile, allow me to finish with this very funny curbside (at least funny to us).

Yes, I know — ID geek jokes. 80s mosquito, ha.

Sorry.

September 25th, 2016

Is There a Hospitalist “Bounce-Back” to ID?

The New England Journal of Medicine recently published two outstanding pieces on hospitalists, and they had pretty much diametrically opposing perspectives.

Both should be required reading for anyone practicing medicine, and indeed anyone who might know — or be — a patient in a U.S. hospital one day.

In short, everyone.

But since you may not have time, let me give you the condensed versions:

Wachter and Goldman, “Zero to 50,000 — The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist”: The hospitalist movement is booming because hospitalists increase the efficiency — and possibly also the quality — of inpatient care.

Gunderman, “Hospitalists and the Decline of Comprehensive Care”: Due to the their limited training, narrow focus, and frequent shift changes, hospitalists inherently weaken the doctor-patient relationship, and may negatively impact patient care.

Both pieces make valid points, and you will probably find yourself nodding with recognition as you read each one. But rather than comprehensively review them, I want to focus first on the issue of greatest relevance to Infectious Diseases, in particular the recruitment of fellowship applicants — money! As creators of the very term “hospitalist” (they should have patented it), Wachter and Goldman provide a concise historical overview of how the field emerged out of multiple aligned forces, the first (and arguably the most important) being financial:

How could hospitalists, then, fashion careers out of a role that was economically unattractive to their colleagues? Once evidence of substantial cost savings had accumulated, health care organizations found it advantageous to have hospitalist programs, and most provided financial support to create appealing jobs with reasonable salaries.

In short, so valuable is a short length of stay to a hospital’s bottom line that essentially all hospitalist positions have subsidized salaries. They also have substantial “time off”, with many positions offering full-time salaries for part-time hours — 7-on, 7-off is a popular (if much-debated) model.

Tough for ID (or any non-procedural specialty) to compete! Indeed, many cite the abundant well-paying hospitalist positions available to internal medicine graduates as the primary driver of the decline in applications to ID and nephrology programs. In an interview I conducted with fellow ID-docs Wendy Armstrong and Mike Edmond recently on Open Forum Infectious Diseases, both brought their A-game (listen!), and what Mike said about hospitalists vs ID positions rings particularly true:

We are seeing an increase in debt burden for students as they complete medical school and go into residency, so that factor is becoming a heavy one on their minds. We have a lack of salary parity with fields that require less training than being a subspecialist in infectious diseases … ID is essentially asking people to do more training in order to make less money, and I think for many residents in internal medicine that’s just a non-starter.

But there’s hope for us yet, and it’s primarily because some of those in hospitalist work are doing so not because of the work itself, but for other reasons.

While I must emphasize that there are many hospitalists who have chosen the field because it’s an excellent way to be directly involved in patient care and, often, quality improvement, teaching, and clinical research, some are doing it primarily for the money because they must — they have too much medical school debt. If so, there’s a decent chance that the hospitalist position will eventually prove something less than career (or soul) nurturing.

For another group, the choice is also expedient — this is good money for part-time work. For this group, it’s not hospitalist work as a career destination, but primarily a way to subsidize their other medical or non-medical activities that are less remunerative — international work, teaching, business start-ups, administrative aspirations, novel-writing.

As an example of the latter, how about U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek Murthy? He was an excellent hospitalist at the Brigham (brush with greatness, I know) for several years, primarily while pursuing the activities cited in his official biography in his “time off”. It’s either appropriate — or ironic — that he’s cited by Wachter and Goldman as validation for the prestige of the hospitalist position!

Getting back to ID, we’re smack dab in the middle of fellowship interviews, and I’m pleased to report that we still see outstanding applicants to our field — superb clinicians, brilliant researchers, esteemed teachers, thoughtful humanists.

And a substantial number of them have spent the last year or two as hospitalists. They have used those temporary positions to pay-down some of their medical school debt so that they can eventually train in the field that they’ve always loved — ID. They are excited to begin exploring ID in depth, and often somewhat disgruntled by the churn of admissions and discharges that is inpatient medicine in 2016.

Full disclosure, this “hospitalist bounce-back” phenomenon is anecdotal — I don’t have actual numbers to back this up.

But I’m curious to hear if others are experiencing the same thing, both in ID and other fields.

Now for a different kind of “bounce-back”…

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aS3xaXsh6vo]

September 18th, 2016

Ten Years After Landmark HIV Testing Guidelines, How Are We Doing? Specifically in Emergency Departments?

In the late 1990s, a patient was admitted to our hospital with HIV-associated PCP. He had advanced AIDS, a CD4 cell count < 100, and was sick enough to require a temporary stay in our ICU.

In the late 1990s, a patient was admitted to our hospital with HIV-associated PCP. He had advanced AIDS, a CD4 cell count < 100, and was sick enough to require a temporary stay in our ICU.

Those clinical details aren’t so remarkable — “late” diagnoses of HIV still happen, and happened even more back then. What’s remarkable is what happened to him before he got admitted.

As an (early) freelance web designer, he had no medical insurance, and received his infrequent care through an emergency department at a hospital near his apartment. He had gone there around a month before we admitted him with cough and weight loss; no pneumonia was seen on his CXR at that point. He told the doctor who saw him that he was worried he had AIDS since he was a gay man and hadn’t been tested in many years.

According to the patient, the doctor there told him that he was right to be concerned, but that the policy of the ED was that they could not do HIV tests. He urged him to see a primary care doctor soon after discharge from the ED to get this checked.

Never happened — he didn’t have a primary care provider. His illness smouldered along for a while, until it became severe enough that he was admitted here with pneumonia. He said repeatedly that if he knew he was HIV positive, then he would have sought care much earlier.

When I told this story to someone from our ED way back then, they said the same thing — that it was a “policy” (unwritten, but widely agreed upon) that they should not send HIV tests, even if they clinically suspected a patient had AIDS.

One of our current Emergency Medicine doctors, Kelli O’Laughlin, explains:

Historically there is a sentiment in emergency medicine that energy and resources in the emergency department should be reserved for dealing with urgent medical conditions rather than on diagnosis of chronic medical issues. Additionally, emergency medicine clinicians have avoided testing patients in the ED for HIV because of the concern results will return when the patient is no longer in the ED. This can make it challenging to share results with the patient, which can expose physicians to legal risks. Other barriers to HIV testing in the ED include lack of provider knowledge and comfort with pre-test counseling and post-test counseling.

Well a lot has changed with HIV testing since the late 1990s, most notably the landmark CDC HIV testing guidelines, issued almost exactly 10 years ago today. (Happy 10th Birthday!) Those guidelines have been critical in reducing the proportion of people in the USA with HIV who are unaware of their status (now around 10-15%), allowing those with HIV to get life-saving treatment before getting AIDS-related complications, and preventing further HIV transmissions.

While the guidelines are often cited for recommending an HIV test for most US adults and removing the requirement for written informed consent, just as important was that they specified where HIV testing should take place — namely “all health-care settings.” If that’s not clear enough, this is:

The recommendations are intended for providers in all health-care settings, including hospital EDs [emphasis mine], urgent-care clinics, inpatient services, STD clinics or other venues offering clinical STD services, tuberculosis (TB) clinics, substance abuse treatment clinics, other public health clinics, community clinics, correctional health-care facilities, and primary care settings.

I don’t think it’s an accident that hospital EDs are listed first among health-care settings in the CDC testing guidelines. As noted here:

HIV disproportionately affects populations that are likely to be without a regular source of care or have a history of barriers to care, which may contribute to delayed diagnosis and further transmission of HIV. Many are dependent on the public sector for the financing and delivery of their care. … Consequently, EDs — whose patients include large numbers of underinsured and uninsured — are likely the only source of health care for many people with HIV or at risk for HIV.

And what about guidelines about HIV testing specifically from the American College of Emergency Physicians? They’re in agreement, and have been since 2007.

This post is undoubtedly “preaching to the choir” — who reads an ID/HIV blog, after all? — but the main reason I’m writing it is not just because of the impending 10 year anniversary of the CDC guidelines, but to underscore just how difficult the culture shift has been in certain EDs around the country.

Including, ahem, ours. And, since misery loves company, the situation is even worse at one of our “partner” hospitals (which will go unnamed, but is also commonly abbreviated with three letters).

Writes Kelli:

Despite CDC recommendations for HIV screening in health-care settings, in our own emergency department, ironically, we do not have processes or systems in place to make HIV testing efficient. We cannot ensure that abnormal results will reach the patient. I experienced this problem over a year ago when a patient I tested for HIV was discharged from our emergency department observation unit without receiving his/her abnormal result of the initial HIV screening test. Fortunately we were able to locate this patient shortly after. Motivated both by the gap between CDC recommendations and our practice, as well as this individual case, I worked with colleagues to establish the HIV Testing in the ED Committee.

I’m confident that with Kelli’s leadership, it will become a reality soon. Already I can tell that our ED clinicians are ordering more HIV tests, and we’ve been collaborating with them to ensure that any positive results are given an expedited evaluation by an ID doctor.

What’s the situation where you work?

September 11th, 2016

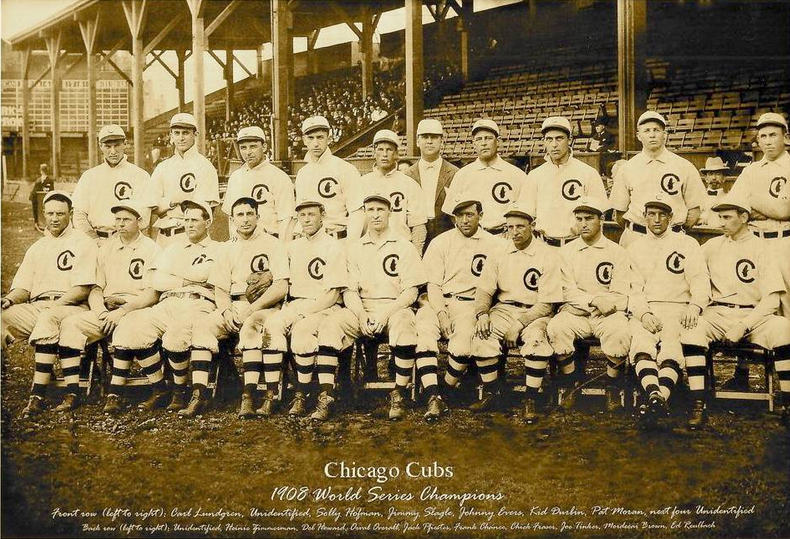

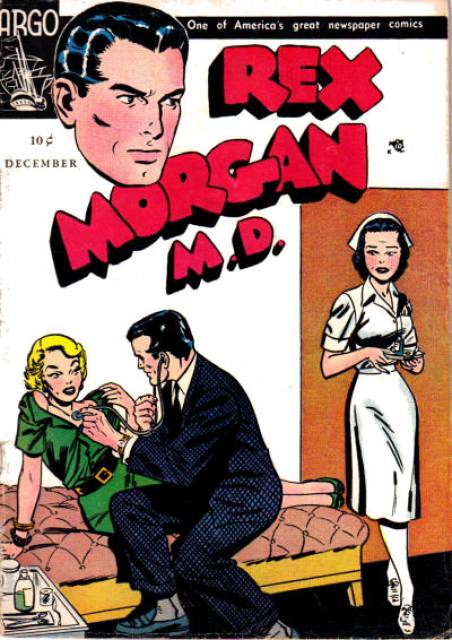

Poll: More on Morgans, and Vote on Your Favorite Cartoon Caption

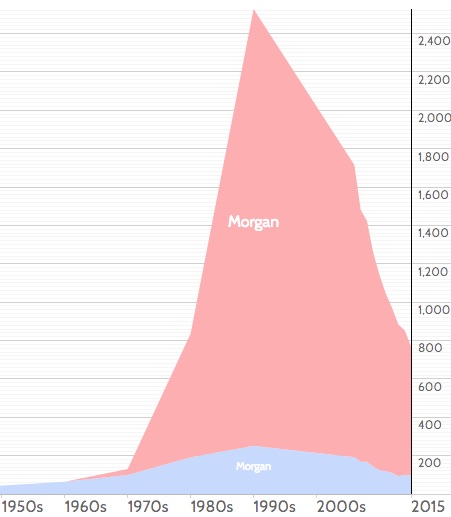

During my last post on the new HIV testing algorithm, I mentioned that I’d recently met a doctor named “Morgan” for the first time. I also provided actual data why this might be an unusual name for a doctor today, but, rarity notwithstanding, we should anticipate more examples of “Morgan —-, MD” soon.

During my last post on the new HIV testing algorithm, I mentioned that I’d recently met a doctor named “Morgan” for the first time. I also provided actual data why this might be an unusual name for a doctor today, but, rarity notwithstanding, we should anticipate more examples of “Morgan —-, MD” soon.

At the end of the post, I wrote: “And if there are any other doctors named Morgan out there, I look forward to hearing from you.”

The topic prompted a curious series of emails between certain esteemed editors at NEJM Journal Watch and me. Below, a (heavily edited and augmented, but bones are unchanged) version for your perusal:

Esteemed Editor #1 (EE#1): Hey, did you hear from any doctors named Morgan?

Me: Not yet. But in 10 years — there will be plenty! They will be banging down my door! Look at that graph! It really does seem to be a “generational” kind of name … You must know plenty of Morgans. [She’s much younger than I, hence my comment.]

EE#1: I personally know ZERO Morgans.

Me: Hey, how old are you? I’m figuring that most Morgans are in their late-20s-30s around now. My nephew is getting married this weekend, he’s around 30. Bet he knows some Morgans.

EE#1: Almost 46!!!! [Note the 4 exclamation points.] I could have a kid named Morgan. But all of my imaginary kids are named something else.

Esteemed Editor #2 (EE#2), who has been cc’d on these critical emails, but thus far is playing it cool: Are you implying that you think we are in our 20s? If so, we will love you forever. The only Morgan I know is the one from the Mindy Project.

Esteemed Editor #3 (EE#3), who’s also been cc’d and now can’t resist weighing in: Morgan Fairchild… not a millennial. Born in 1950! [The internet is cruel.]

EE#1: Yeah, pretty much the only one I’m familiar with.

Me: Morgan Freeman too, though I think of Morgan Fairchild as the true pioneer in the Morganization of the USA. And let’s face it, most of the young Morgans out there are females.

EE#1: Right, it’s a unisex name. But more XX than XY recently.

EE#2: I can’t believe I forgot about Morgan Freeman! And he won an Academy Award, didn’t he?

Me: It was for The Shawshank Redemption. [I don’t really know this, but state it very confidently, at least if there’s an email equivalence of confidence. Guys love “The Shawshank Redemption.” And I’m counting on the fact that we’re all so “busy” — as evidenced by these emails — that they’ll never fact-check me. Oh well.]

EE#1: Wrong! Per Wikipedia: “Freeman won an Academy Award in 2005 for Best Supporting Actor with Million Dollar Baby (2004), and he has received Oscar nominations for his performances in Street Smart (1987), Driving Miss Daisy (1989), The Shawshank Redemption (1994) and Invictus (2009).” So nominated for Shawshank, but didn’t win. In fact, nominated for a lot!

Me: Did you fact-check Wikipedia? [I got no response to that one.] Our readers would think I’d completely lost my mind if I wrote another blog post about doctors and Morgan, but there just might be enough material here.

EE#1: Well, I’m the blog manager for your blog (and technically I report into EE#2 for this portion of my job). So, she might object to your Morgan-obsession. : ) I’ll defer the final decision …

EE#2: No objection from me! Make it hilarious. [That will be your assessment. I’m doing my best!]

EE#1: Maybe do a two-topic post, in which Morgan is only one of the topics.

Me: Actually, I was just kidding.

EE#1: Darn, I wish you were serious! Have a nice evening, all!

Ahem.

ID doctors, of course, are probably wondering, in our geeky way, about whether this all started with Morganella morganii, which is possibly fueling my obsession. Double Morgans, after all! And there’s a pretty famous comic with a Dr. Morgan name (see above picture), but his first name is Rex. Emphatically not Morgan.

On the subject of comics, it’s time to vote on your favorite caption for our last cartoon. After culling through the entries and submitting them to the usual rigorous testing, we’ve arrived at 3 top candidates for this fine drawing. Please vote!

September 4th, 2016

The Most Common Question About the New HIV Testing Algorithm, Answered

A primary care doctor in the Boston area recently emailed me this question:

A primary care doctor in the Boston area recently emailed me this question:

Hi Paul,

A 28yo woman had a positive 4th gen +Ag/Ab assay, but a negative HIV-1/2 differentiation assay and negative HIV viral load. She had no signs of acute HIV, but is not using condoms with her partner, whose HIV status she doesn’t know. We repeated the test yesterday and she is again Ag/Ab+, the remainder of the test is pending. If we get the same results again, would you try to get a Western blot?

Thanks,

Morgan

[Not her real name, but I did just meet a doctor named “Morgan” for the first time, so feel compelled to comment here. If you look at this name popularity graph, I guess we have an explanation for the rarity of this name among MDs to date. Did you know Morgan was the 30th most common girl’s name in the USA during the 1990s? So expect more Morgan MDs soon!]

“Morgan’s” question has come up numerous times since the new algorithm kicked in, and it reflects a misunderstanding of what the newer tests can and can’t do.

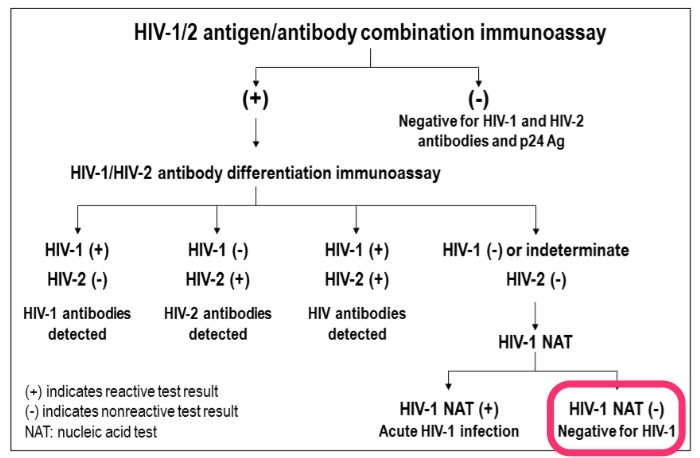

Remember, the big advance in moving from the 3rd to the 4th generation screening test was the addition of p24 antigen to the sensitive ELISA antibody. This shortens the window period from HIV acquisition to a positive screening test by about a week.

The second big change is that the confirmatory test is now a differentiation assay, an antibody test that tells us if the person has HIV-1 or HIV-2 — the Western blot couldn’t do that. If it’s negative, an HIV RNA (viral load or other nucleic acid test, NAT) is recommended, since the screening test (with its antigen component) is more sensitive early in disease than the differentiation assay. Importantly, the Western blot — may it R.I.P. — offers no advantage in sensitivity over the FDA-licensed differentiation assay (in fact, it’s a bit worse), so won’t be of help in these cases.

However, if the HIV RNA is negative, then we’re dealing with a false-positive screening test, and this is exactly the scenario in the email. For relatively low-risk patients, this is a far more common explanation for the positive 4th generation screen/negative differentiation assay pattern than true acute HIV infection, just as it was for a reactive ELISA with negative Western blot.

How much more common? In this review (pages 34–36) by the primary architect of the algorithm, Bernie Branson, we get some numbers:

The specificities of 4th generation HIV assays are >99.6% — which means that as many as 40 per 10,000 test results may be false-positive. In most populations of persons testing for HIV, the prevalence of acute HIV infection is 2 per 10,000 persons tested or less. Thus, the frequency of false-positive immunoassay results usually far exceeds the prevalence of acute HIV infection.

For those who prefer all this stuff explained graphically, here’s the key figure from the latest HIV testing guidelines; I’ve highlighted this case’s results in bright fluorescent pink:

To summarize:

- The 4th generation screening test shortens the window period after HIV acquisition.

- The differentiation assay tells us if the person has antibodies to HIV-1 or HIV-2.

- In screening test positive/differentiation test negative cases, the next step is an HIV RNA (or other NAT).

- Most (but not all) will have a negative HIV RNA, and therefore don’t have HIV.

In other words, false-positive screening tests will continue to happen — even with the new algorithm.

Thank you very much for your attention, and enjoy this amazing video, which must have taken its creator many, MANY hours to complete. Wow.

And if there are any other doctors named Morgan out there, I look forward to hearing from you.

(H/T to IMS for the video, though it looks like many millions of people have beaten us to it.)

August 27th, 2016

ID Cartoon Caption Contest #1 Winner — and a New Contest for the End of Summer

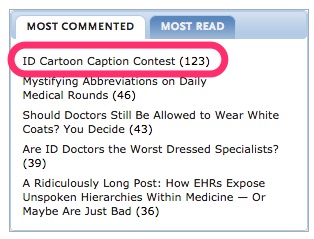

All blogs worth the price of admission have a sidebar, and this one is no exception.

Critical components include (but are not limited to) the following:

- The Option to Subscribe — Go ahead, you know you want to. It’s right over there to the right. Just enter your email address and click subscribe — no username, password, or two-step verification required. Then, kind of like colonization resistance, the notifications you’ll get of a latest post here will help crowd out those dubious invitations to conferences in China, Dubai, or Malaysia, the requests to submit papers for the The Journal of Infectious and Non-Infectious Diseases, and the people who are trying to sell us CRISPR reagents.

- The Search Box, where you can enter diverse topics such as “Should I curbside ID about whether to give the rabies vaccine?” or “Why does he hate the term HAART?”

- The Most Popular Posts list, which here is called, “Most Commented,” with another tab for “Most Read.”

In case it wasn’t obvious enough, I’ve highlighted that the first ID Cartoon Caption contest drew quite a response. If we add in entries that were sent to me directly via email, there were well over 200 submissions. Not bad for a debut performance.

Anyway, here’s the winner of ID Cartoon Caption Contest #1:

The winner was Dr. Michael Dantzer, who has kindly given me permission to use his real name (I assume it’s his real name). As promised, he gets a free lifetime subscription to this blog and, of course, lasting fame and fortune.

He also sent me a nice note praising my excellent sense of humor in picking his entry as a finalist. It should be noted, however, that the selection of his entry as a finalist relied not so much on my subjective sense of what’s funny, but a highly complex algorithm that includes not only scientifically validated humor criteria but also gas liquid chromatography and multiplex PCR.

Anyway, it’s high time for a new contest. Summer is about to end, Labor Day cookouts loom, and we must be vigilant to the ever rising threat of both foodborne pathogens and carcinogenic heterocyclic amines:

Go at it. Put your entries in the comments section (preferred), on my Twitter feed, or email it directly to id.caption@yahoo.com.

(Drawing by Anne Sax, of course.)