An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

April 12th, 2020

IDSA’s COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Highlight Difficulty of “Don’t Just Do Something, Stand There”

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) gathered a series of experts for what were undoubtedly many late-night calls, reviews of published and pre-print literature, and revisions (of revisions), and admirably generated a set of treatment guidelines for COVID-19.

The problem — there is no proven effective treatment for COVID-19.

That is, there’s no proven treatment based on our usual highest standard metric for efficacy, the randomized clinical trial — nor the next-best thing, a carefully done observational study that meticulously accounts for potential confounders.

Which means these guidelines have a Groundhog Day-like quality. In a series of clear and comprehensive sections, they review the available evidence, then repeatedly conclude the same thing:

The IDSA guideline panel recommends the use of [insert putative COVID-19 treatment here] in the context of a clinical trial. (Knowledge gap.)

Well, not exactly the same thing — for some of these treatments they insert the word “only”, yielding “… only in the context of a clinical trial.”

Here’s the difference between the two, according to the lead author:

For interventions with certainty regarding risks and benefits, the expert panel recommended their use “in the context of a clinical trial”. The guideline panel used “only in the context of a clinical trial” for interventions with higher uncertainty and/or more potential for harm.

But the message is clear. We don’t have sufficient evidence now to recommend any specific treatment.

That’s right — for chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin, tocilizumab, corticosteroids for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), lopinavir/ritonavir — all are readily prescribable by clinicians (each is FDA-approved for other indications), yet none is proven to work for COVID-19.

That might be hard to believe given the publicity surrounding some of the approaches, in particular hydroxychloroquine. But those are the facts as of today.

So where does that put clinicians on the front lines managing this new disease?

Highly conflicted.

Hey #IDTwitter and other clinicians who are caring for people with #COVID19. Have you prescribed (or recommended) hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for this infection? Please vote and comment. Thank you!

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) April 11, 2020

Those favoring the use of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 say that there is at least some evidence that hydroxychloroquine helps — enough so that controlled studies are ongoing. We certainly don’t have anything else to offer, and people are sick!

Plus, there’s a plausible mechanism of action, with in vitro antiviral activity. Maybe even two mechanisms if we consider the anti-inflammatory effect.

In addition, there’s this comment, posted by a critical care specialist in response to my poll:

Yes. No idea if it works, but it’s plausible, and it’s part of the YNHH [Yale New Haven Hospital] treatment algorithm for now. Wonder if those on the only-clinical-trials high horse have ever prescribed Haldol for agitated delirium?

High horse, ivory tower, unconnected to “real practice” — these are common charges levied at academic medicine, with some justification. Certainly not everyone has access to clinical trials.

And even when clinicians do have access to these studies, not all patients meet inclusion criteria, and some others might choose not to participate.

Indeed, at our hospital — which, like many academic medical centers, both has clinical trials for COVID-19 and prides itself on following evidence-based medicine — approximately a third of our COVID-19 cases have received hydroxychloroquine.

(Thanks to our crack ID PharmD Jeff Pearson for the quick data review.)

But why just a third? Why not all of them?

Let’s take up the nay-sayers view. They cite the weakness of the data. One study was, on further scrutiny, so flawed the journal publishing it raised concerns about the low quality of the study. How often do we see that?

Another trial has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal, was quite small, and showed improvement in some minor endpoints only — with tremendous heterogeneity in other treatment approaches.

Furthermore, people already receiving hydroxychloroquine for rheumatologic indications have already acquired COVID-19 — how effective can it be? Plus, there’s an abstract of a study (inadvertently circulated before publication) that not only shows no benefit, but also suggests harm.

If we have questions about clinical benefit, all must acknowledge that any treatment can cause harm. Of particular concern with hydroxychloroquine for elderly patients — those at greatest risk of severe COVID-19 disease — is QT prolongation, a problem worsened with concomitant azithromycin, many other medications, and underlying heart disease.

Is it any wonder the poll results are so split? This is a real tough one.

Often in such circumstances, it’s helpful to ask what one would do for a loved one — or yourself — if having to make the decision.

Personally, I would not take hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19, concerned about side effects and not so sanguine about its potential antiviral activity. The road is littered with drugs that have in vitro activity for respiratory tract infections, and yet do nothing when given to people.

In fact, our list of effective antiviral treatments for these infections is very short! For common respiratory tract infections, we have only the influenza drugs — and even with the flu, some argue the benefits are marginal.

I do understand the opposite view. I would listen carefully to a patient who strongly wanted treatment and go forward with prescribing it, provided they understood the risks and there were no contraindications.

But a well-designed clinical trial? Sign me up. We’ve got to learn more about this disease, and fast.

So take it away, Mabel and Olive. You two are giving me great pleasure at a time when we all really need it.

April 6th, 2020

Dear Nation — A Series of Apologies on COVID-19

(What I’m sincerely hoping we’ll be hearing in an upcoming press conference, and soon.)

(What I’m sincerely hoping we’ll be hearing in an upcoming press conference, and soon.)

Dear Fellow Americans,

I’d like to take a brief moment in today’s press briefing to say something that is long overdue.

I’m sorry.

In a moment, I’ll cite the specifics of what I’ll be apologizing about.

But first, I want to acknowledge the sadness of this spring. I see our parks, fields, and forests coming alive with beautiful flowers and trees in bloom, but see none of the exciting vitality, diversity, and spirit that characterizes our great country.

Here in your nation’s capital, the cherry blossoms bear witness only to a sad silence. I imagine they are in mourning for the terrible losses already inflicted by this cruel virus. No doubt many of you have experienced losses yourself — I offer you my deepest, and most heartfelt condolences in your grief.

Now it’s time for me to apologize. By doing so now, I hope to chart a path forward so we can work together to end this devastating threat.

Let me apologize for dismantling programs put in place to deal with global infectious threats.

Acting like a reality TV host instead of a leader, I fired Tom Bossert — he was Homeland Security Adviser and coordinated the response to pandemics. I also let Tim Ziemer go — he was the head of global health security on the White House’s National Security Council. I then shut down the entire global health security unit.

Then Dr. Luciana Borio, the National Security Council’s director for medical and biodefense preparedness, left as well. Like Ziemer and Bossert, my administration never replaced these talented individuals — I confess these moves greatly weakened our ability to respond to infectious threats.

Dr. Borio tried to warn us in late January what was coming. I’m sorry for not heeding that warning.

I also apologize to the reporter who asked me about these actions, and I called her questions “nasty” — that was an inappropriate and disrespectful response. You were correct to challenge me on these moves, as have many others in these exchanges. Going forward, I promise to engage in productive dialogue with an understandably interested press corp.

I have repeatedly proposed funding cuts to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), where many positions also remain unfilled. I even did this after COVID-19 had already appeared in our country. I’m sorry about that.

In addition, I have taken away the CDC’s lead role in navigating and monitoring a response to the outbreak, silencing their regular briefs during infectious threats. The CDC workers are dedicated public health professionals who deserve our respect, and our thanks. They tried to issue a broad warning in late February, one we should have heeded.

Instead, I downplayed their warnings. I’m sorry to them, and to you, for this misdirection.

I apologize for all the times I’ve mentioned that media coverage of COVID-19 is politically motivated. Such comments only serve to drive us further apart at a time when we need to be working together.

In other words, from now on, no more of this:

Low Ratings Fake News MSDNC (Comcast) & @CNN are doing everything possible to make the Caronavirus look as bad as possible, including panicking markets, if possible. Likewise their incompetent Do Nothing Democrat comrades are all talk, no action. USA in great shape! @CDCgov…..

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 26, 2020

I’m sorry for not accepting the WHO COVID-19 test when first offered to the United States, for not moving more quickly to remedy our initially flawed tests, and for the ongoing struggles you experience even today with testing.

I did not help matters by saying in mid-March that COVID-19 testing could be obtained easily by any doctor, and that the tests were perfect. This clearly misled the public, causing more confusion — I apologize for that.

I’m sorry for calling the virus that causes COVID-19, which is SARS-CoV-2, the “Chinese virus”. Such medically inaccurate comments only encourage racism.

I’m sorry for saying to those working at overrun and beleaguered hospitals that they are exaggerating their need for lifesaving equipment such as ventilators. To the Governor of New York, I admire the selfless leadership you are displaying as our country’s largest city grapples with this terrible health threat.

To those of you on the front lines, putting your health and your family’s health at risk to care for people with COVID-19, I apologize for not doing enough to protect you. Despite what you have heard from our administration thus far, the federal stockpile should be there for all of us.

I also am sorry for the patchwork system in place for distributing these materials, which does not appear to be equitable.

Moreover, I apologize for implying that we already have an effective treatment for COVID-19, when such statements need the support of carefully done clinical studies.

Mostly, I’m sorry for the lies, half-truths, impulsive attacks, and bullying I’ve been responsible for ever since this horrible pandemic spread around the world. At times I confess financial and market forces, along with politics, motivated my actions more than personal and public health. I deeply apologize for that.

Many, including myself, have said we’re at war right now. Indeed, some aspects of this struggle are similar to war, when all a nation’s resources must be mobilized against a common enemy.

But wars pit people against people, so the comparison doesn’t quite fit, especially in a time when human kindness and caring are so important. In the fight against this infection, it isn’t other people who are enemies — it’s the virus.

Let’s work together to fight it.

Thank you.

(This song was co-written by Adam Schlesinger, who died last week of COVID-19 at age 52.)

March 26th, 2020

No Opening Day … Yet

My memories of spring have always included baseball.

I worshiped my older brother Ben — he’s still pretty great — and he loved baseball. So as the days in March shifted from cold and dark to slightly less cold and much less dark, the game he played so brilliantly with his friends pulled me in. I was hooked.

I became so obsessed with baseball that my mother recalls hearing me talk about it in lengthy, excruciating detail — our “conversations” became tedious enough that she would intermittently say “yes” or “mmm” or “wow” just to pretend she was actually listening.

(Mom, all is forgiven.)

When the warm weather truly kicked in, I played various pick-up games pretty much every day — stickball, fungo, softball, Whiffle ball, some rubber-covered indestructible ball that had the same size and weight as a baseball, but survived concrete and pavement. We made up rules since we never had full teams.

No hitting to right field. No walks. No base running — played with “imaginary” runners on base. A cleanly-fielded grounder was an out since no one played first. A ball in the trees was a home run. Over the trees was a Grand Slam, even if no one was on base.

The rectangle-shaped strike zone painted on the school brick wall would have to suffice for every player — didn’t matter if you were Jose Altuve- or Aaron Judge-sized.

Also, there was Little League, then baseball for my school teams. Take a look at that keystone combo in the photo!

Meanwhile, I read everything I could about the sport — its rich history, the great players and the teams, the remarkable games, the endless statistics. A memorable (to me) 4th grade class presentation on Ty Cobb consisted of my listing, with astonishment, his stratospheric batting averages each year:

“… .382, .419, .409, .389 … .383, .382, .384 … .389, .401!”

Now that was an exciting report. One of my classmates bluntly told me afterwards she’d never heard anything so boring in her life.

Today was supposed to be Opening Day for the 2020 baseball season.

But COVID-19 had other ideas, halting Spring Training and delaying the start of the season until who knows when.

“You don’t make the timeline, the virus makes the timeline,” says the wise Dr. Fauci. This version of how long we’ll be dealing with COVID-19 strikes me as much more grounded in science than Mark Cuban’s.

As a result, while usually we cue up this brilliant passage about baseball from Bart Giamatti at the end of the season, how about now?

It breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart. The game begins in the spring, when everything else begins again, and it blossoms in the summer, filling the afternoons and evenings, and then as soon as the chill rains come, it stops and leaves you to face the fall alone. You count on it, rely on it to buffer the passage of time, to keep the memory of sunshine and high skies alive, and then just when the days are all twilight, when you need it most, it stops.

“Play ball!” can’t come soon enough.

March 22nd, 2020

Quiet Hospital Zone

Academic medical centers right now would provide visitors — if they were permitted — a strange experience.

Academic medical centers right now would provide visitors — if they were permitted — a strange experience.

Usually buzzing with clinical and research activity, with incessant human interactions in hallways, on rounds, at the bedside, in conference rooms, our hospitals are now eerily quiet — and very, very, tense.

Minus the intensive care units, the “special pathogen units” (or whatever name assigned to them), the emergency room — the rest of the place is practically silent.

Elective ambulatory care has basically shut down. Same for elective surgeries.

Scheduled for screening colonoscopy? Cancelled.

Annual mole check with your dermatologist? Rescheduled for 3 months (at least) from now. Hernia repair? Sorry.

Follow-up with your nurse practitioner about that new blood pressure medication? Virtual visit — better get that home blood pressure monitor out from the closet.

The inpatient floors have, as usual, patients with acute medical and surgical problems — but discharges occur expeditiously, with signs at the hospital entrance prohibiting visitors. This is no place anyone wants to linger. The hospital census is way down.

As for conferences, they are all but done. Medical grand rounds, clinical case conferences, morbidity and mortality, resident report — all cancelled, or converted to Zoom, or Webex, or GoToMeeting, or Skype, or whatever your platform may be.

The cafeteria still serves food, but there’s no self-serve anything, a tricky pivot for an enterprise that usually offers many buffet choices. Forget the salad bar. A long-term kitchen employee — Pat, she’s wonderful — wears a mask and kindly hands you your cup of soup, using plastic gloves and plenty of distancing.

No groups congregate at the tables — which are pushed to the side of the room. Don’t sit here.

The cashiers have a wary look on their face — please don’t hand me cash — but to their credit, are as friendly as ever.

Quiet. Hospital Zone.

March 16th, 2020

Difficult Times — Meaning No CROI Really Rapid Review 2020

In a usual year, right about now, I’d be obsessed with two things:

In a usual year, right about now, I’d be obsessed with two things:

- What were the most practice-changing studies presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, or CROI? I’d want to summarize those for a patented, copyright-protected, check-with-my-lawyer-before-copying, Really Rapid Review©®.

- How will the upcoming baseball season play out? Most readers here don’t care, I concede. Oh well, we all have our enthusiasms.

But this isn’t a usual year, especially not for us specialists in Infectious Diseases.

Baseball is on hold for now, thank you coronavirus — they say two weeks, but everyone knows it will be longer. Who knows.

As for CROI? Due to some remarkable sleight of hand, at the last minute it became a virtual meeting, with research and plenaries presented online. The planners moderated the sessions in place right here in Boston — but no one attended live.

I thought about writing a Really Rapid Review©® on this electronic CROI.

But I was so distracted by COVID-19 activities that it was tricky. (Ok. Impossible.) Today I concluded that the product wouldn’t meet the high standards of those who read this site regularly, for which you have my sincere gratitude.

Meanwhile, you can take a look at this isolated citation from the conference. I do think it is the most important practice-changing study from CROI 2020 — how often do we see randomized clinical trials in pregnant women with HIV?

(HARDLY EVER. There, I answered.)

It’s called IMPAACT 2010. And with the disclosure that I’m a (relatively unimportant) co-investigator on the study, and obviously some disappointment that it didn’t get the attention it deserved, here’s a take-home message — DTG + TAF/FTC may well be the best regimen for treatment-naive pregnant women.

Important, practice-changing RCT presented a #CROI2020 on Rx of HIV in pregnancy. Take-homes:

– DTG superior to EFV in viral suppression

– TAF/FTC+DTG best for adverse pregnancy outcomes

– Weight gain most with TAF/FTC+DTG; closest to rec wt changes @IMPAACTNetwork pic.twitter.com/6mNWstFbVX— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) March 11, 2020

Meanwhile, if you want to know how your fellow ID doc feels right now, take it away Adi:

Medical professionals internally right now pic.twitter.com/vYlABMUycv

— Adi (@IDdocAdi) March 16, 2020

Thank you for your patience. And take care of yourself during this difficult time.

March 8th, 2020

As Testing Ramps Up, Diagnoses of Coronavirus Disease in the U.S. Will Soon Increase Substantially — How Will We Respond?

Brace yourself. As coronavirus disease (COVID-19) occurs at multiple locations around the United States, the number of confirmed cases here is about to increase big time.

There are two reasons:

- New infections

- More testing

Believe it or not, despite statements by certain politicians, COVID-19 tests still cannot be ordered by any clinician who believes it should be done. In many parts of the country — including, as of today, Massachusetts — a local health department continues to be the only place to get the test. These state labs have limited resources, and hence must offer the test only to those who have a clear exposure, or have a severe respiratory illness without other obvious cause.

That’s about to change. Two of the largest commercial labs in the country, LabCorp and Quest, announced that they have tests ready to go.

Plus, multiple academic medical centers plan to modify their existing molecular diagnostic assays by adding the coronavirus genetic sequence as a target. This will enable testing to be done rapidly “in house” at hospitals that see the highest volume of critically ill and immunocompromised patients.

And not a moment too soon. By all objective measures, our testing has been woefully inadequate, meaning that the reported number of diagnosed COVID-19 cases are the proverbial tip of the iceberg — an iceberg of the pre-climate change magnitude.

Consider — today’s report shows 484 cases reported with 20 deaths. Remember that these tests were done mostly on the sickest people. That’s why our mortality rate is so high at 4.1%.

By contrast, consider South Korea, which already has widespread disease and an aggressive testing policy (they have apparently done over 140,000 tests). They have diagnosed 7,314 COVID-19 cases, with 50 deaths, for an estimated mortality rate of 0.6%.

If we apply that 0.6% mortality rate to the 20 deaths we’ve had here, this would mean there are already around 3,000 cases in the United States. We just haven’t been testing enough to find them.

(Apologies to epidemiologists for the crude estimates. Hey, math is hard.)

There are several ways we could — as clinicians, scientists, media, public — react to this surge of cases that will inevitably dominate the headlines in the coming weeks.

On the negative side is panic, which will bring with it further hoarding behavior, conspiracy theories, and unproductive accusations. On this last one, I’d like to emphasize what I posted here about the people I know who work at CDC and the department of public health — they are not to blame:

Agree. The people I know who have worked at @CDCgov and at @MassDPH have been hard-working, mission-driven, and science-based individuals who want to do the right thing. They must be given the resources they need. https://t.co/iukkqLkRMb

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) March 7, 2020

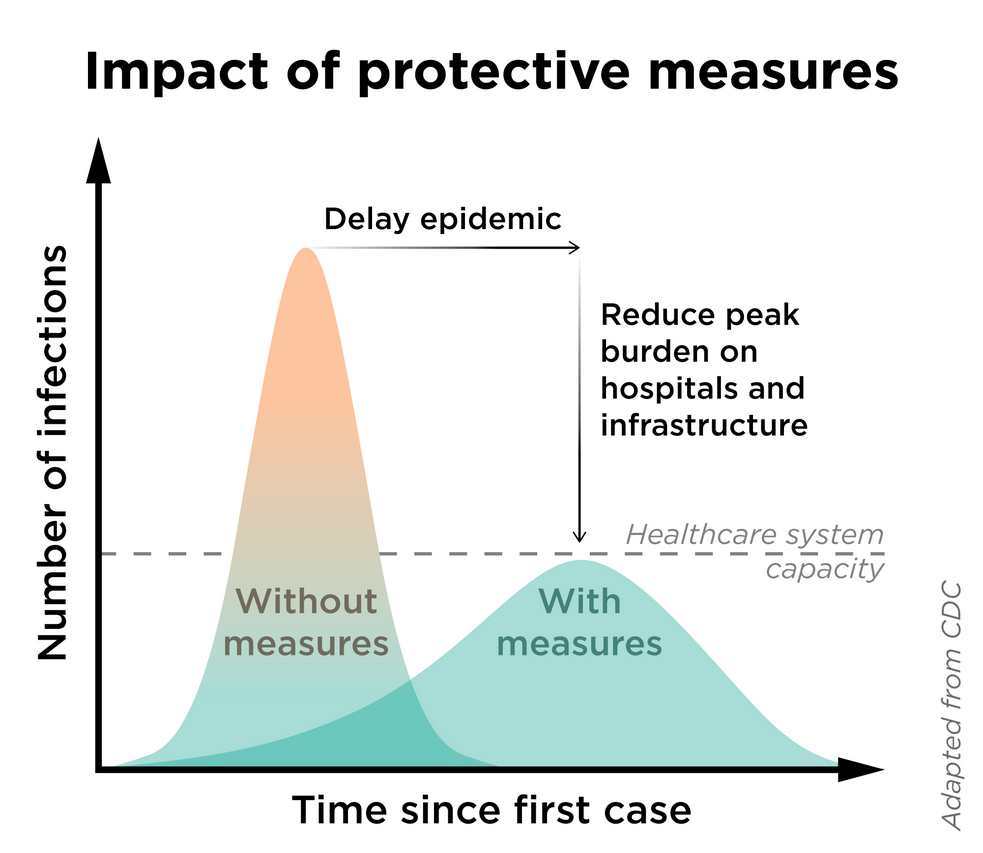

Another terrible reaction will be to suppress the information.“I like the numbers being where they are” is not an effective mitigation strategy — a strategy which will be critical to prevent the overburdening our healthcare system (see figure).

What I’m hoping for?

Let’s welcome the accurate data, even though the numbers will sound scary. It’s time for expansive tests for COVID-19, even introducing them as soon as possible on our multiplex respiratory virus testing platforms.

Such information will give us a much better sense of the spectrum of the illness here, as well as the risk factors both for COVID-19 acquisition and severe disease. It will also allow us to institute more sensible infection control policies, to allocate resources where the disease is most prevalent, and to construct viable strategies to turn the tide against the epidemic.

When Knowledge is Power confronts Ignorance is Bliss during a public health emergency, give us the first one every time.

March 6th, 2020

CROI 2020 Will Be a “Virtual Meeting” After All — Plus, What Scares Me (and Doesn’t) About Coronavirus

This just in:

BREAKING NEWS: #CROI2020 will be a virtual meeting this year! Thanks to @IAS_USA @DonnaJacobsen and all CROI leadership for wrestling with this difficult decision and putting public health first. https://t.co/KPmJ66x7GL

— Melanie Thompson (@drmt) March 6, 2020

If you’re a frequent reader of this blog, you might have read here just minutes ago that it was going ahead after all — with a discussion about how difficult it must have been for the organizers to make the decision.

Never mind. Kudos to all of them for remaining nimble in this uncertain time.

As for the coronavirus situation, there are some things I truly fear — and others, not so much.

I was asked to write about them on WBUR’s CommonHealth. Many thanks to Carey Goldberg for this idea, and coming up with the excellent title.

February 25th, 2020

First Week on Service, with One-a-Day ID Learning Units

There is almost always something to be learned from every new patient.

There is almost always something to be learned from every new patient.

It might be buried somewhere in the history, or the physical, or the lab tests, or the micro, or the imaging — but the odds are excellent that, with enough rumination, you’ll find it.

I can’t remember now who taught me this important fact, or even if it was ever explicitly stated to me. Quite possibly it was just implied — or personified in action — by some really smart, impressive clinical mentor. Someone skilled in finding that nugget of learning in every case.

It might have been my legendary residency program director; or the World’s Greatest Chief Medical Resident (I’m still missing her, sadly); or the brilliant Chief of ID during my fellowship; or the most intuitive ID clinician on the planet.

(FYI, that last guy remains an invaluable resource on tough cases.)

Regardless, these ID Learning Units are out there. And here are seven — one-a-day — from my first week on the inpatient ID consult service:

1. Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis. You’ll have an “a-ha” moment the first time you see this strange and challenging entity.

Day #1: Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis (CNGM) is a chronic inflammatory process, associated with corynebacterium spp. (Causal?) Optimal management remains unclear–generally involves combination of abx and corticosteroids. @Yijia_89 https://t.co/RjeerNHSb6

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 19, 2020

2. Consider pulmonary arteriovenous malformations when encountering a brain abscess, especially if there are no other obvious risk factors.

Day #2: Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations are a risk factor for bacterial brain abscess; some have a history of recurrent nosebleeds, with visible mucocutaneous telangiectasias on exam. Suggests all brain abscess pts should be screened for PAVM. https://t.co/KAtOECbJOn

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 20, 2020

3. Chronic meningitis — must be one of the most difficult diagnoses in all of ID.

Day #3: Chronic meningitis is CSF pleocytosis that persists for at least 4 wks without spontaneous resolution. ID, autoimmune, and neoplastic processes may be causative; up to 30% no Dx. Next gen sequencing may help. @Yijia_89 @rose_m_olson https://t.co/ZAbUMFOljW

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 21, 2020

4. A convenient cefazolin dosing strategy in hemodialysis — thanks to Dr. Chris Bland, who pointed out this even better study. A real game-changer for inpatient ID consult services everywhere.

Day #4: Cefazolin dosed post-hemodialysis is an ideal strategy for treating MSSA infections in patients with ESRD, obviating the need for a PICC line or other catheter. Excellent PK; good outcome in this small clinical study of bacteremia. https://t.co/nfRca4S49t

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 22, 2020

5. With cutaneous lesions that may be zoster, PCR is the diagnostic test of choice — much better than both culture (which lacks sensitivity) and direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) testing, which is highly dependent on getting enough cells.

Day #5: PCR is the diagnostic test of choice for cutaneous VZV, greatly surpassing viral culture in sensitivity (and also much less operator dependent than DFA). Of course in many cases, clinical diagnosis is sufficient! https://t.co/pt3z80fecA

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 23, 2020

6. You know those patients with a positive syphilis screening test, a positive confirmatory test, but a negative RPR? Well, as we’ve discussed before, they’re quite unlikely to have neurosyphilis.

Day #6: In a study of 265 CSF exams, not a single case of neurosyphilis was diagnosed among those whose blood VDRL was negative. Similar study from Hopkins with RPR. h/t Khalil Ghanem https://t.co/lkyu3sNiKL pic.twitter.com/ptk0ScztFy

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 24, 2020

7. When scanning your HIV patient’s historical genotypes, if you find Y188L, that eliminates the entire NNRTI class of drugs. It’s also naturally present in all HIV-2 isolates.

Day #7: Universal resistance of HIV-2 to NNRTIs is due to the Y188L polymorphism, which appears in all HIV-2 isolates. (Similarly, when seen in HIV-1, Y188L confers resistance to all NNRTIs, including doravirine, +/- etravirine.) @Yijia_89 https://t.co/tpeGG1Upgn

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 25, 2020

February 17th, 2020

Short-Course Treatment of Latent TB, Combination Therapy for Staph Bacteremia, Adult Vaccine Guidelines, Novel Antifungals, and Others — A Non-COVID-19 ID Link-o-Rama

There’s so much out there right now on COVID-19 (the disease) and SARS-CoV-2 (the virus) that the other ID news gets crowded out.

Which means it’s time for non-COVID-19 ID/HIV Link-o-Rama! I haven’t done one of these in a while, so there’s plenty of material in the vaults yearning to be free.

- The CDC now recommends short-course, rifamycin-based, 3- or 4-month latent TB infection treatments as preferred over 9 months of isoniazid. Completely agree, as 3 or 4 months seems so much shorter than 9 months. Important reminder — watch for rifampin-related drug interactions! Will the 1 month of rifapentine plus isoniazid regimen be in the next version of these guidelines?

- Among patients with MRSA bacteremia, addition of an antistaphylococcal β-lactam to standard antibiotic therapy with vancomycin or daptomycin did not overall improve outcomes. While persistent bacteremia was numerically reduced with combination therapy, vancomycin plus an antistaphylococcal penicillin led to a higher rate of renal injury, prompting the DSMB to stop the study early. This safety issue was not observed with cefazolin, so vancomycin plus cefazolin is still being studied in a separate trial. Excellent summary from the lead author Steven Tong here.

- Ceftaroline plus daptomycin combination therapy may reduce mortality in patients with MRSA bacteremia. This retrospective, matched cohort study supplements favorable findings on this combination from an earlier, small, randomized trial. Some appropriately cautionary commentary from the lead author Erin McReary here. Unfortunately, it does not appear that a randomized study of this combination is in the works due to the cost of the drugs and lack of interest from the manufacturers. Let’s continue the staph bacteremia theme but move on to MSSA with …

- Cefazolin and ertapenem appear to rapidly clear persistent MSSA bacteremia. This uncontrolled study describes 11 patients for whom this combination treatment quickly cleared blood cultures. The authors postulate that ertapenem “rescues” the relatively attenuated activity of cefazolin against MSSA, noting that certain microenvironments (such as bacterial endocarditis vegetations) might make this reduced activity clinically relevant. That’s enough Staph bacteremia for now!

- The latest DHHS HIV guidelines have added dolutegravir (DTG) plus lamivudine (3TC) as a recommended initial regimen. This is the first time a two-drug regimen has garnered this status. Appropriately, there is accompanying cautionary language about excluding baseline HIV RNA > 500,000, chronic hepatitis B, and transmitted M184V. With the encouraging data on this highly effective two-drug regimen, I ask — what’s the purpose of abacavir/3TC/DTG, which is also still listed?

- The TANGO study showed that people with viral suppression on tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)-based treatments can safely switch to DTG/3TC. Switch strategies will likey account for most of the use of this DTG/3TC regimen, since for initial treatment, it’s still easier to go with TAF/FTC/BIC or TAF/FTC plus DTG (no need to know baseline viral load, resistance, or hepatitis B status). And another dance-named study — SALSA — will expand this switch population to anyone who doesn’t have resistance to either 3TC or DTG (no baseline TAF regimen required). No reason why the results of SALSA will be any different than TANGO, but of course surprising things do happen. And no, I don’t know what either of these acronyms stands for.

- The cost of antiretroviral therapy in the United States is high — and increasing faster than the rate of inflation. In 2012, the yearly average wholesale price for recommended initial regimens was $25,000 to $35,000, increasing to $36,000 to $48,000 in 2018. While hardly anyone pays this full price due to insurance, the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP), patient assistance programs, and other funding mechanisms, even paying part represents real hardship for some patients — especially concerning since high out-of-pocket costs negatively impact adherence.

- Immunization for zoster may reduce the risk of stroke. In a review of Medicare data, receipt of the live zoster vaccine was associated with a 20% reduction in the risk of stroke for those younger than 80. Note that the data analyzed preceded the availability of the recombinant zoster vaccine, which is more effective in preventing shingles than the live version. Since zoster is a potential trigger of stroke, would we see an even greater decline in stroke incidence with the newer vaccine? A compelling additional motivation for immunization.

- Roughly $42 million was spent responding to measles outbreaks in 2019 alone. In addition to the huge cost of controlling these outbreaks, there is also the opportunity cost for public health departments and their staff — who have plenty of other work to do. So annoying.

- Another state has a bill to eliminate “religious” exemptions for vaccines. Strongly support these bills! These non-medical exemptions for children are particularly insidious, as clinicians out of respect may not want to question patient preferences based on religious beliefs. But the reality is that no mainstream religion actually prohibits vaccinations, which is why I put “religious” in quotes.

- The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) released its 2020 Adult Immunization Schedule. As anticipated, they formally endorse some changes hinted at previously — notably no longer recommending pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV-13) for all adults older than 65 (“consider” based on preference), and supporting the HPV vaccine up to age 45 if patients have ongoing risk for new infection.

- Approximately 8% of mycoplasma isolates in the United States have evidence of resistance to macrolides. Difficult to estimate the clinical implications of this resistance, since we rarely isolate mycoplasma in clinical practice and such testing is only available in research laboratories. Regardless, fluoroquinolones and doxycycline likely retain activity, along with the recently approved drug lefamulin — an antibiotic I still haven’t had the opportunity (or cause) to use.

- Here’s a mega-review of investigational antifungal agents. Rezafungin, ibrexafungerp, olorofim, fosmanogepix, et. al. — the gang’s all here! An incredibly useful paper, especially for those of us not actively involved in antifungal research.

- In a retrospective, multicenter, cohort study done in the VA system, empiric anti-MRSA therapy for patients hospitalized for pneumonia was associated with worse clinical outcomes — even in those at risk for MRSA. By using some serious statistical gymnastics, the investigators examined data from 89,000 admissions to emulate a clinical trial result. Can you say “inverse probability of treatment–weighted propensity score analysis using generalized estimating equation regression” and explain it, please? Still, it’s another cautionary note about unnecessary broad-spectrum therapy and a real boost to antimicrobial stewardship efforts to stop empiric vancomycin.

- Dr. Aditya Shah, an ID Fellow at Mayo Clinic, continues to make us laugh. How about this one from last week?

When the attending supervises the procedure you are doing #stewardmeme https://t.co/WqEIaJ2W8O

— Adi (@IDdocAdi) February 16, 2020

Adi was kind enough to join me on an OFID podcast to discuss what motivates and inspires him to post these memes — highly recommended!

February 9th, 2020

Should Medical Subspecialists Attend on the General Medical Service?

As I’ve written about many times on this site, one of the highlights of the year for me is when I attend on the medical service — something I’ve been doing pretty much forever.

As I’ve written about many times on this site, one of the highlights of the year for me is when I attend on the medical service — something I’ve been doing pretty much forever.

There’s a wonderful learning exchange that goes on, with my knowledge of ID being repaid in kind by the others on the team — interns, residents, nurses, pharmacists, other attendings — who bring me up to date on current general medicine outside of ID.

(Including the acronyms. Yikes!)

I tried to capture this flow of information by commenting on this highly amusing post by Mayo Clinic’s Dr. Adi Shah — and hence confess was taken aback by this comment from Dr. Stephen Shafran, an ID doctor from Canada:

https://twitter.com/ShafranStephen/status/1215526965697896449?s=20

This is an important perspective, one which we subspecialists should examine carefully. How can we ensure that the care and supervision we provide be as safe as that done by a generalist?

This concern has been on my mind the past few weeks, prompting posting of this poll:

Hey #medtwitter, picking up on a classic @IDdocAdi meme from earlier this year, I ask this question — is it ok for medical subspecialists to attend on a general medical service? Why or why not?

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) February 8, 2020

While the results are reassuring, this is hardly scientific — clearly many of the people who participated are ID specialists themselves, and probably many of them also attend on general medicine.

So, where are there actual data? I searched for studies on clinical outcomes for generalist versus subspecialist inpatient attending — and came up with very little.

One study from a single academic medical center suggested that hospitalists had more efficient use of resources (shorter length of stay and costs) than rheumatologists and endocrinologists, but clinical outcomes (readmissions, mortality) were similar. So, is it really unsafe?

As for the trainee experience, this group from UCSF argued strongly that having subspecialists as medical attendings greatly enriches their learning, and might motivate residents to pursue a given subspecialty as a career.

In the absence of definitive information, allow me to list certain strategies that I hope mitigate the safety issues Dr. Shafran raises.

- Those of us subspecialists who choose to do inpatient medicine generally maintain certification in Internal Medicine as well as our specialty.

- It’s very much a self-selected population of subspecialists who choose to do general medicine.

- The subspecialists well-represented on general medicine services have, in their day-to-day activities, a substantial amount of general medicine in their practice — both inpatient and outpatient. There’s a reason you won’t see many subspecialist attendings on medicine who spend most of their time inserting coronary stents or doing ERCPs.

- Obtaining consults on cases outside of one’s comfort zone is encouraged, and never considered a sign of weakness.

One other thing, perhaps specific to our hospital, is the structure of our medical team. The rotations typically pair us subspecialists with hospitalists or outpatient generalists. While only one doctor can be the attending of record for a given patient, the team has two attendings, both hearing about all cases on rounds. More on this team structure here.

After the above exchange occurred on Twitter, I received the following kind email from Dr. Badar Patel, one of our interns:

The experience I’ve had with subspecialists serving as our general medical attendings have all been extremely positive, and I don’t believe we’ve had safety issues as the Twitter thread would suggest. I am interested in medical education and would love to be involved if an opportunity to study this in a formal manner were to come up.

For a start, he’s created a survey about this issue, and already sent it to our house staff.

If you’re in clinical medicine, we’d be thrilled if you would take it as well — here’s the link. All responses are anonymous. We plan to write up the results in a future perspective piece.

And who knows, maybe we’ll learn something! After all, we all have the same goals — better care for our patients, and a better learning experience for our trainees.

Thoughts, comments, and opinions on this topic most welcome!