An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

November 15th, 2020

Bamlanivimab for COVID-19 — Hard to Pronounce, Even Harder to Give

The latest COVID-19 treatment made available under Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) is bamlanivimab, a monoclonal antibody developed by Eli Lilly. For now, its use will be limited to outpatients who are at high risk for severe disease and/or hospitalization.

This EUA is based on the results of the phase 2 BLAZE-1 study, in which the treatment reduced the need for hospitalization among outpatients — especially those deemed at high risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes. For this group, 3% of bamlanivimab versus 10% of placebo recipients required admission.

And yes, you read that right — bamlanivimab.

The comedians sure had a field day with this tongue-twister, and boy it’s devilishly hard to say.

But let me focus instead on the difficulty of actually giving this product to a stable, high-risk outpatient with COVID-19 — because remember, that’s the only way it’s going to help anyone.

I’ve been ruminating over the challenges of implementing this treatment for a while, ever since research began on this class of drugs. Pharmacist Tim Gauthier’s outstanding summary amplified my concerns when he wrote that the logistics of administration would be “considerable” — which could be the understatement of the year.

Why so difficult? Let me list the ways:

- Supply is limited. Even accounting for the high-risk criteria listed in the EUA, the potentially eligible recipients will greatly exceed the number of distributed doses. How bad is the mismatch? This excellent review by my ID colleagues Drs. Robert Goldstein and Rochelle Walensky estimates that based on current case counts, the supply could be exhausted in less than 2 weeks. How will we choose who gets it?

- It must be given within 10 days of symptom onset. Some experts think even 10 days is too long a wait for effective intervention — the sooner the better. While we don’t know the precise window of opportunity for benefit, remember that these monoclonal antibody treatments (from both Lilly and Regeneron) don’t appear to help people already in the hospital.

- It must be given intravenously. How many outpatient clinicians have the ability to give infusions in their clinics?

- People with early COVID-19 disease are at their most contagious. Most secondary transmissions happen between 1 day before and 5 days after the onset of symptoms, during which time respiratory viral load peaks. And this is precisely when we’ll want to bring patients in for treatment.

- Most infusion centers have a high proportion of patients who are immunocompromised. Rheumatology, GI, and neurology patients receiving intravenous immunosuppressive agents. Cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. How can we safely bring COVID-19 patients into these centers? Should we even try?

- Many infusion centers are not set up for urgent referrals. Their regular patients have regularly scheduled infusions. Even setting up an urgent dose of ceftriaxone can be challenging if the schedule is already full.

- Both the infusion and the post-treatment monitoring take a lot of time. This isn’t a simple matter of showing up, getting one quick shot, then leaving. The infusion takes 1 hour, and there is a 1-hour monitoring period afterward to ensure no severe allergic reactions ensue. Budgeting 3 hours seems about right.

- Emergency departments do not want a 3-hour treatment clogging up their patient flow — especially if they don’t get paid. Unlike most infusion centers, hospital emergency departments do have the required infection control capabilities. However, would they welcome stable COVID-19 patients sitting around getting a 3-hour treatment? If so, how many? Not only would this distract from other critical activities, but under current systems of reimbursement for ED visits, there is no guarantee that the hospital will be paid for this service.

- The formulation is tricky to prepare and not stable for very long. Tim’s a pharmacist, so let me just quote him directly: “Preparation of the IV admixture is not simple and is stable for just 7 hours at room temperature or 24 hours under refrigeration (including infusion time).” Ugh.

- Serious side effects may occur. Although not in the published paper, the package insert cites at least one case of anaphylaxis and another serious infusion reaction among banlanivimab-treated patients. As a result, we are advised that this treatment “may only be administered in settings in which health care providers have immediate access to medications to treat a severe infusion reaction, such as anaphylaxis.”

Practically, these gargantuan logistical hurdles may make the limited supply moot — all of us are trying to figure out how to deliver this promising treatment to prevent hospitalizations, and it’s not an easy nut to crack.

But already there’s a sense that these difficulties could exacerbate existing disparities in COVID-19 outcomes, with underserved populations missing out again on the benefits of this tricky treatment.

Let’s imagine a hospital or other healthcare delivery system sets up a program to administer banlanivimab to people diagnosed with COVID-19 as outpatients. Because of drug supply constraints and the duration of the infusion and monitoring time, they limit the number of treated patients to two per day (a morning and an afternoon session), which is to be administered in a specialized infusion site separate from immunocompromised patients.

Patients are referred by their primary clinicians, or they can call themselves. An intake nurse or other health professional speaks with them, reviews the relevant medical history, and ultimately determines whether they meet the “high-risk” criteria for treatment. If so, they schedule the patient for one of the two daily treatment slots.

Sounds simple, right?

Now let’s consider two imaginary (but quite plausible) patients newly diagnosed with COVID-19, both of whom would meet eligibility criteria for banlamivimab therapy.

The first is a 74-year-old semi-retired lawyer with hypertension and adult-onset diabetes. He could lose a few pounds, so tries to play tennis at his club in Wellesley as often as possible. He gets regular check-ups in the hospital system’s primary care network. Because of that network, he periodically receives health alerts through his hospital’s patient portal, including reminders to schedule his eye exams, blood tests, and immunizations.

The second imaginary patient is a 71-year-old woman from the Dominican Republic who moved to Boston five years ago to live with her daughter and grandchildren. Although she worked at a restaurant before she moved (gaining quite a few pounds with on-the-job snacking), she now finds the language barrier difficult here, so does not work. She mostly stays at home, sometimes socializing with other older people in her neighborhood who also speak Spanish. She receives some primary care at her local community health center; they have recommended that she start treatment for high blood pressure and diabetes, but the clinicians keep changing, and not all of them speak her language, so she never did.

Which patient is most likely to be referred for a banlanivimab infusion? Which one is more likely to call and advocate for themselves?

I suspect no one needs a medical degree to answer those questions.

November 10th, 2020

Promising COVID-19 Vaccine Results and Progress on HIV Prevention — All in One Great Day

Monday, November 9, in the bedeviled year 2020, was an astounding day for research on prevention of infectious diseases — really unprecedented.

First — we awoke to hear that the Pfizer-BioNTech experimental COVID-19 vaccine was “90% effective” in preventing the disease after the second (of two) doses.

This was a planned interim analysis, taking place after 94 cases had occurred in 44,000 volunteers, with 39,000 completing the full series. No major safety concerns yet reported.

We of course need to review the full data, but these results are far better than any of us expected. For other viral respiratory infections, we have flu vaccine at one extreme of efficacy (20-50%, depending on the season), and measles at the other (90% or higher, and lifelong). Who could have predicted that the first SARS-CoV-2 vaccine result would be closer to the latter?

My ID colleague Dr. Mark Siedner and I wrote a primer on how to interpret the data, when they come out. Check it out!

Second — we learned the results of a critical HIV prevention study, HPTN 084, which compared TDF/FTC given once daily to injectable cabotegravir given every 8 weeks in HIV-negative women in Africa. Over 3000 women were enrolled at sites located in Botswana, Eswatini, Kenya, Malawi, South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.

Thirty-four HIV infections occurred in the TDF/FTC arm vs only four in the cabotegravir arm, a nearly 9-fold difference. As with HPTN 083 done in men who have sex with men and transgender women, the TDF/FTC strategy was effective, but the cabotegravir strategy significantly more so — a difference big enough in 084 to prompt the safety monitoring board overseeing the study to recommend stopping the blinded phase of the trial.

In a background of disappointing PrEP studies conducted in this population (African women), these results are particularly impressive. And because the Pfizer vaccine study dominated the day’s news (understandably), you might have missed this — hence I’m highlighting it here.

Wow, what a day. Thanksgiving came early in 2020, didn’t it?

November 1st, 2020

A Series of Disappointing Results of Immune-Based Therapies for COVID-19

It’s been a tough couple of weeks for immune-based therapies for COVID-19.

It’s been a tough couple of weeks for immune-based therapies for COVID-19.

We know that immune modulation in this disease, especially in its most severe manifestations, can improve outcomes.

Favorable results from the RECOVERY study of dexamethasone have made it the standard of care for most hospitalized patients who require oxygen. And we also know that our own immune system plays a major role in clearing this nasty virus.

So can we succeed with more targeted approaches? Either inhibition of our overly exuberant immune response or “boosting” our own immune systems through monoclonal antibodies?

(Some might classify the latter as antivirals rather than immune-based therapies. How about considering them both?)

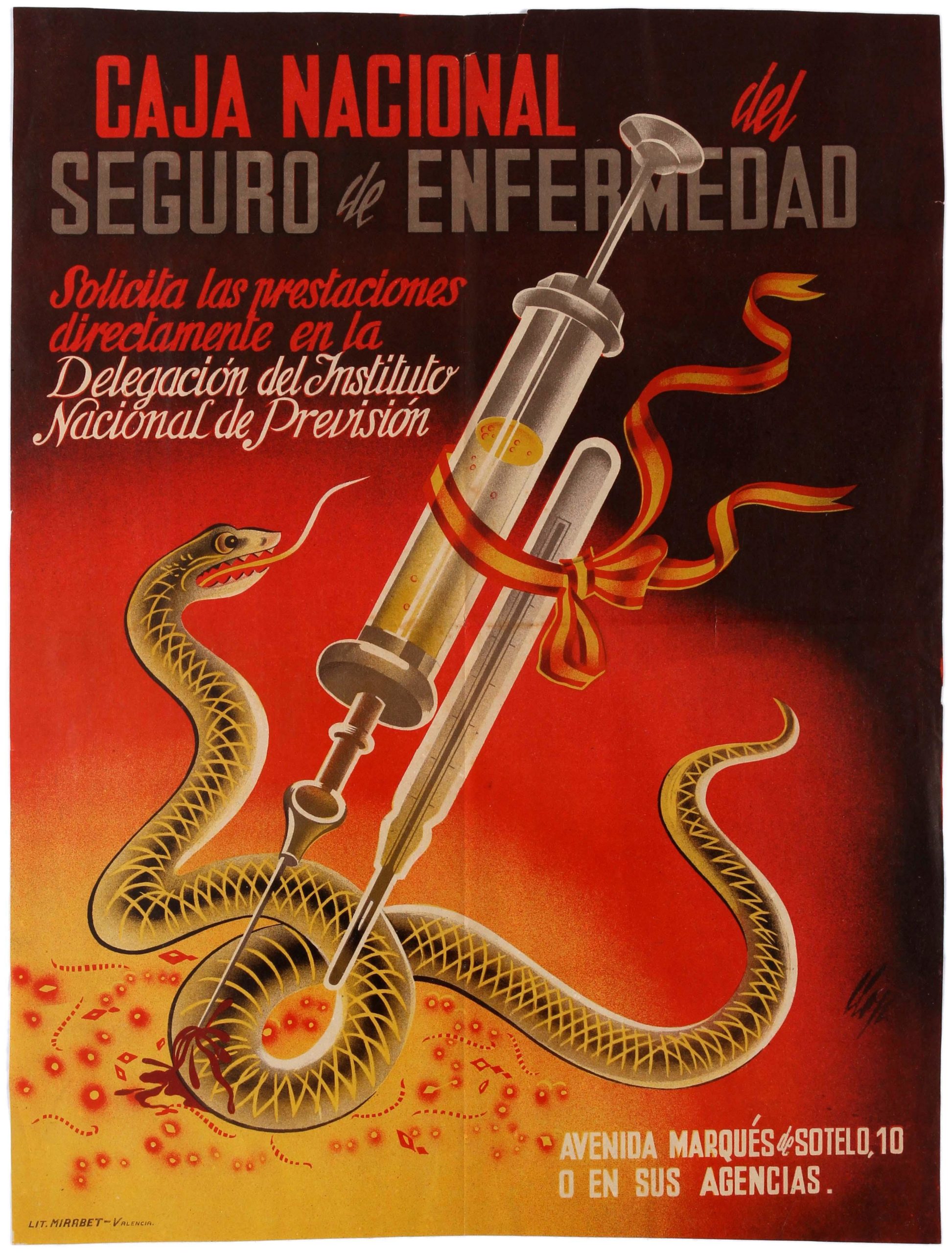

Let’s start with tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 (IL-6) inhibitor widely used off-label for treatment of COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic. Multiple observational and small prospective studies also strongly suggested clinical benefits.

Well, in a remarkable 48 hours late last month (October 21-23, to be exact), no fewer than four multicenter randomized clinical trials of tocilizumab appeared in print — three in peer-reviewed journals and one as a pre-print. All were done on hospitalized patients not receiving mechanical ventilation, and all compared tocilizumab with a “usual care” control.

- RCT-TCZ-COVID-19 (n=126): The primary endpoint was hypoxemia (protocol defined), ICU admission, or death. Investigators stopped the study early due to futility.

- CORIMUNO-19-TOCI-1 (n=131): Two endpoints were of primary interest — scores higher than 5 on the WHO 10-point Clinical Progression Scale (WHO-CPS) on day 4, and survival without need of ventilation (including noninvasive ventilation) at day 14. Tocilizumab did not demonstrate efficacy on the first measure and “might” (I quote the paper) have reduced the need for mechanical ventilation (results were borderline). No impact on mortality.

- BACC Bay Tocilizumab Trial (n=243): Unlike the first two, this was a placebo-controlled trial, with a 2:1 randomization to tocilizumab or placebo. Tocilizumab did not significantly reduce the requirement for intubation or mortality, the primary endpoint. Since the confidence intervals around the point estimate for benefit or harm were wide, the study could not exclude either one.

- EMPACTA (n=389): Also placebo-controlled, this study’s primary endpoint was death or mechanical ventilation by day 28. Here, tocilizumab did reduce the risk for mechanical ventilation, but mortality at day 28 was not improved — strangely, it was numerically higher with the treatment (10.4% vs 8.6%). (The study is not yet peer-reviewed.)

If that’s not enough, a September press release on the largest randomized study — COVACTA, with 450 participants — did not meet its primary endpoint of improved clinical status nor the secondary endpoint of reduced mortality.

What can we glean from this flurry of study results? I agree with this excellent review by Dr. Jonathan Parr, who wrote that the findings “do not support routine tocilizumab use in COVID-19.”

Oh well. Time will tell whether any secondary benefits from this targeted and powerful immunosuppressive accrue, but given its extremely high cost and potential adverse effects (including increasing risk of infection), we should not be using tocilizumab in routine clinical practice for COVID-19.

But at least we’ll soon have monoclonal antibodies, right? Well, monoclonal antibodies are promising — but if they work, and if so in what patients, both remain unclear.

What does appear clear is that the monoclonals in late-stage clinical trials — being developed by the companies Lilly and Regeneron — don’t improve outcomes in severely ill hospitalized patients. First, the NIH halted the study of LY-CoV555 in this population:

The Data Safety Monitoring Board reviewed data from the ACTIV-3 trial on Oct. 26, 2020 and recommended no further participants be randomized to receive LY-CoV555 and that the investigators be unblinded to the data. This recommendation was based on a low likelihood that the intervention would be of clinical value in this hospitalized patient population.

This followed an action-pausing enrollment in that study for a possible safety issue, but ultimately, the decision stemmed from a lack of benefit, also known as a futility analysis. Importantly, study of LY-CoV555 continues in outpatients with COVID-19, who may yet benefit as evidenced by a reduced need for hospitalization in the phase 2 study.

Next, Regeneron announced it had halted its own study of REGN-COV2 (an antibody “cocktail”) in patients requiring high-flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation, citing both a lack of efficacy and a potential safety concern. Could “immune enhancement” be playing a role? The trials of this treatment in other patient populations continue.

If REGN-COV2 rings a bell, that’s because it’s one of several therapies given to the president during his stay at Walter Reed Medical Center. It’s also part of the larger RECOVERY study conducted in Britain, and these negative results will prompt a data review by the study’s independent Data Monitoring Committee.

So neither antibody treatments worked in the more severely ill COVID-19 patients. And if they end up as promising treatments for milder disease — and I hope they do — imagine the logistical hurdles required to administer these intravenous therapies to outpatients with COVID-19. The mind boggles.

Let’s finish with the latest discouraging newsflash on COVID-19 immune-based therapies, this time with anakinra, the interleukin-1 (IL-1) inhibitor:

Same story again for #COVID19 drug claims:

* an open-label single arm study with "matched control" (à la Raoult) claims mortality reduction with anakinra (NCT04357366)

* French ANSM sets the RCT testing anakinra on hold for a death imbalance in anakinra arm… (ANACONDA-COVID-19)— Bertrand Delsuc (@BertrandBio) October 30, 2020

The halted study — yes, called ANACONDA — compared anakinra versus optimized standard of care in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. It was open-label, with a planned enrollment of 240, and a primary endpoint of “being alive and not requiring any invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).”

And now it has been halted due to excess mortality in the intervention arm. Ouch — the worst possible outcome. More details to come.

How about the favorable observational studies?

As with tocilizumab, these data can be highly misleading, even when explanatory models show that the treatment should work. Our brains have a tendency to make up scientific rationales for treatments that we want to work, it’s just something we can’t help doing. Such instincts are stronger than our ability to identify and control for all potential confounders.

As for these disease models, let’s remember that the immune system is oh so complicated — at its best, fine-tuned to protect us from pathogens, but not so strong as to cause uncontrolled autoimmune disease.

Just like we can’t open up a broken computer and disconnect random wires or remove various circuit boards to fix it, we can’t selectively suppress the immune system and expect favorable outcomes when treating a new disease. Which is why, ultimately, all of these treatments need data from controlled clinical trials before they can be broadly adopted.

It’s hard work, and it takes time, but it needs to happen.

October 25th, 2020

(Not) Attending Professional Meetings in the COVID-19 Era

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), our professional society, held its annual meeting this week, IDWeek.

As usual, I registered for and attended the meeting.

Of course I should have written “attended” the meeting, as instead of having an in-person meeting in Philadelphia (the original planned venue), it was entirely done online. Another “virtual” meeting due to COVID-19.

First, the good news. The preparation and content both were top-notch. Navigating the site, watching the presentations either live or on-demand, and reviewing the posters, I found the experience transparent and bug-free. (No pun intended.)

Happy to report there has been real progress in the virtual meeting user interface since the last conference I “attended”.

And there is gobs and gobs of content. (Or should that be “are gobs and gobs” — inquiring minds want to know!)

That’s the great thing about IDWeek — there’s so much to hear about that you eventually finish the meeting having learned a ton. The top experts in our field weigh in on what they’re experts about –what could be better? It’s especially useful when stepping outside one’s comfort zone.

Now, the not-so-good news — these online meetings can’t come close to replicating the experience of having them live.

To be sure, big in-person work meetings are far from perfect. They’re expensive, require travel (the agonies of which are legion), use up our carbon footprint, and gosh they are tiring from the socializing perspective. Sometimes you just want to sit in your hotel room and hide, and watch the major oral presentations and read the posters online.

Understandably, some doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and other clinicians wouldn’t consider attending these meetings. Too time-consuming and expensive.

But you know what? Doing only the online part misses a lot of what’s great about live meetings. When attending them, you can focus on the meeting, mostly free of the distractions of work and home.

I spent most of last week at work, well, working.

This is very cool. And beautiful! But given my distraction during #IDWeek2020 — you know, with clinic, epic messages, doodle polls, manuscript reviews, slide deadlines (with *learning objectives*), on-line learning modules, zooms, etc, I'm probably this dot way out here. pic.twitter.com/4dkf7C4nh0

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 25, 2020

Periodically last week, I’d remember that IDWeek was in fact still taking place — and then I’d have the double hit of guilt coming from both getting behind in work and the FOMO of not “being” at the conference. Yikes.

One colleague fought this problem by posting this:

Thank you for your email. I am attending a virtual conference, and will not be checking email until October 25. I will respond to your message as soon as possible.

Gives a new meaning to the term, “out of office message,” doesn’t it?

Furthermore, IDWeek in particular always has great community feel to it — these are our people. Really missed that.

What a great chance to network and reconnect. A clump of former ID fellows, now having launched their careers, gathers by a poster — how fun to catch up! A friend/colleague from New York or Los Angeles or Miami or Chicago or Philadelphia or Madrid or Sydney I’d not seen since the last conference — how are you? A person who’s recently made a big splash with a research paper, or a promotion, or by landing a big new job — congratulations!

And the personalities! Here are a few famous ones from my HIV world: Carlos del Rio somehow knowing literally everyone in our field — how does he do that? Jeanne Marrazzo’s enthusiastic and supportive laugh. Joe Eron steps up to the microphone, and asks the most incisive post-presentation questions. John Bartlett with his yellow note pad, sitting in the front row capturing every pearl. (Dating myself a bit with that last one.)

No, canceling in-person academic meetings isn’t the biggest loss dealt us by the COVID-19 pandemic, far from it.

But it’s a loss nonetheless.

October 18th, 2020

Does Remdesivir Actually Work?

Quick answer — it’s complicated.

Let’s start with a clinical anecdote — rightfully considered the weakest form of evidence, yet paradoxically holding great power over us because we’re imperfect humans. It’s the way we’re wired.

In April, a patient of mine with stable HIV came into the hospital with COVID-19 pneumonia. (Certain details changed for privacy.)

She works cutting hair, in a community hard-hit from the pandemic and where mask-wearing was inconsistent. She knew as soon as she developed fever, chills, and back pain that this is what she had.

She must have had symptoms for no more than 36 hours when she arrived at the hospital, and because she has HIV (who knew whether this worsened outcomes?) and is quite overweight, she was admitted.

She enrolled in the SIMPLE study — which compared remdesivir for 5 or 10 days to standard of care, all open-label — and was randomized to the 5-day course. She received her first dose of the drug the night of admission.

Again, she had been symptomatic for no more than 2 days.

The next day, she looked like a new person. Her fever was down, she was breathing more easily, and she told me her back pain went away as soon as the first dose had completed its infusion. She left the hospital on day 3, and made a complete recovery.

Of course, she could have recovered just as quickly without remdesivir — that’s the problem with an anecdote.

But based on this and other cases I saw — and the extensive experience of my indefatigable colleagues Dr. Francisco Marty and his team, who enrolled dozens of patients into this study — I was not surprised when in May, a different and more rigorous remdesivir clinical trial reported significantly faster recovery in the treatment arm than in the controls.

And because this study — called ACTT-1, now with final results — included a placebo arm and was blinded, this provided much stronger evidence that remdesivir actually works. (That’s in the title of this post.) It worked particularly well in people with shorter duration of symptoms and in those requiring oxygen. It didn’t help people so sick that they needed mechanical ventilation or ECMO.

When the data from ACTT-1 became available, we created a construct about these critically ill patients who didn’t benefit from remdesivir. In this view, they were in the immune phase of the illness, where the body’s immunologic response to the infection drove more disease than viral replication.

We can’t expect an antiviral to control these processes. Just like oseltamivir or baloxavir for influenza, you have to act early with remdesivir when treating SARS-CoV-2. Let dexamethasone or some other immunomodulator do the late work.

See, it all fits together perfectly.

But there were always holes in this neat little package.

First, the original remdesivir study from China showed no benefit of treatment. Yes, it was underpowered due to dropping case numbers, but the drug didn’t lower viral loads in recipients either. Concerning.

Second, the open-label study my patient enrolled in had a funny result in the 10-day arm — no apparent benefit compared with standard of care. (The 5-day arm did show benefit.) How do we explain that?

Now we have the interim results of the SOLIDARITY study, at least in preprint form, and that neat little package has even more holes.

In SOLIDARITY, over 11,000 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (from 405 hospitals and 30 countries) were randomized between whichever study drugs were locally available and open control. This included up to five options — four active treatments versus local standard-of-care. The drugs were lopinavir/ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine (remember those?), interferon beta-1a, or remdesivir.

(Based on the limited availability of some of the drugs across countries, the study arms differed in size.)

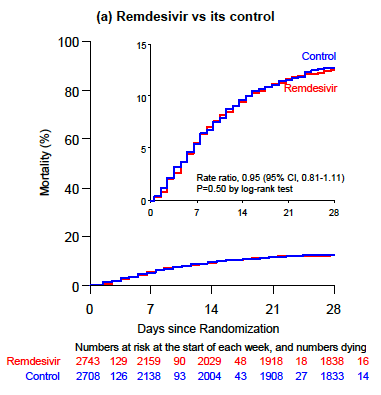

The results for all the interventions failed to show a survival benefit. And the survival curves for the remdesivir arm versus standard of care look depressingly the same:

You could barely draw curves that overlap so precisely. This figure has been emblazoned on the retinas of ID clinicians since the preprint was released last week.

You could barely draw curves that overlap so precisely. This figure has been emblazoned on the retinas of ID clinicians since the preprint was released last week.

So how do we explain these discordant results? We can’t do so completely given the different study designs and populations. But just as how ACTT-1’s benefits can’t overrule the SOLIDARITY results, nor can SOLIDARITY negate ACTT-1 or the 5-day results from SIMPLE.

So let’s put all the studies together, as shown here in this colorful meta-analysis, and exclude patients who are on mechanical ventilation since no study demonstrated benefit in this population:

https://twitter.com/mikejohansenmd/status/1317056317522169856?s=20

First, we’ll note that SOLIDARITY’s much larger sample size trumps (ouch) the other studies. Second, the point estimate just crosses 1 (no benefit), but falls to the left of the line, suggesting (if you squint) some benefit.

If I had to postulate where we’d see the greatest benefit for remdesivir, it would be in patients with shorter duration of symptoms. Even in the negative underpowered study from China, those with fewer days of illness did better than controls. Could it be that the favorable results in ACTT-1 were from the fact that 25% of patients were enrolled with symptoms for 6 days or fewer?

Related, SOLIDARITY began enrollment in March, and for much of the enrollment period, patients with COVID-19 did everything they could to avoid hospitalization. For many, I suspect the short window of time for this antiviral to benefit had closed by the time they were admitted. Duration of symptoms is not reported in the preprint, a critical piece of information.

So for now, the answer to the question, “Does remdesivir actually work?” is a cautious maybe. Sometimes. For some people.

Which, given the absence of anything else right now and its low toxicity, means I’d still recommend it for most hospitalized people with COVID-19 — with the hope of giving it sooner rather than later, especially for those on oxygen at high risk for disease progression.

But if we can learn anything from the mental gyrations required to square these conflicting study results, it’s that we definitely need more effective options.

October 12th, 2020

“Dying in a Leadership Vacuum” — Defended

This past week, the Editors of the New England Journal of Medicine published a piece entitled “Dying in a Leadership Vacuum.”

This past week, the Editors of the New England Journal of Medicine published a piece entitled “Dying in a Leadership Vacuum.”

It’s a scathing indictment of the United States government’s response to COVID-19, in particular our inability to have a science- and evidenced-driven approach to control a disease that has now killed more than 215,000 Americans.

One might ask what purpose such an editorial serves. After all, those who agree with the sentiment (raises hand!) already know, less than a month before election day, how we’re going to vote.

And those who disagree will dismiss its publication as politics as usual.

Never mind that our government’s first comprehensive pandemic response program was started by a Republican president, George W. Bush. The same president who launched the largest global HIV treatment program in history, the President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

There’s hardly an ID specialist out there who didn’t strongly support these important initiatives. So no, this isn’t all about politics.

Another criticism of the editorial, say some doubters, is that it could have the paradoxical effect of driving voters away — confirmation that doctors and scientists are elitist intellectuals with a liberal bias.

In short, it does little more than “making the writers feel good.”

There is perhaps some validity to this perspective — I was accused of the same when writing an imaginary “apology” issued by the president. (Somehow we never heard from him — no surprise.). But it did make me feel better, so guilty as charged on that account.

But still — are there other benefits to such an opinion piece?

I’d say yes. An important counter view is that a pointed editorial from the usually apolitical New England Journal of Medicine signals the severity of the problem we have. Saying nothing would arguably be a political stance as well.

The piece also acts as a convenient way to catalogue some painful data, and highlight our more egregious mistakes. It’s well-written, and accurate, and already has been read over 2 million times. But if you don’t have time to read the whole thing, here are some choice selections.

First, some damming mortality statistics:

The death rate in this country is more than double that of Canada, exceeds that of Japan, a country with a vulnerable and elderly population, by a factor of almost 50, and even dwarfs the rates in lower-middle-income countries, such as Vietnam, by a factor of almost 2000.

Next, our ongoing testing and PPE fiascos:

When the disease first arrived, we were incapable of testing effectively and couldn’t provide even the most basic personal protective equipment to health care workers and the general public. And we continue to be way behind the curve in testing. While the absolute numbers of tests have increased substantially, the more useful metric is the number of tests performed per infected person, a rate that puts us far down the international list, below such places as Kazakhstan, Zimbabwe, and Ethiopia, countries that cannot boast the biomedical infrastructure or the manufacturing capacity that we have.

Our inability to support coherent social policies:

Our rules on social distancing have in many places been lackadaisical at best, with loosening of restrictions long before adequate disease control had been achieved. And in much of the country, people simply don’t wear masks, largely because our leaders have stated outright that masks are political tools rather than effective infection control measures.

How about our usually capable and non-partisan government agencies?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which was the world’s leading disease response organization, has been eviscerated and has suffered dramatic testing and policy failures. The National Institutes of Health have played a key role in vaccine development but have been excluded from much crucial government decision making. And the Food and Drug Administration has been shamefully politicized, appearing to respond to pressure from the administration rather than scientific evidence.

And now, the big finish:

But this election gives us the power to render judgment. Reasonable people will certainly disagree about the many political positions taken by candidates. But truth is neither liberal nor conservative. When it comes to the response to the largest public health crisis of our time, our current political leaders have demonstrated that they are dangerously incompetent. We should not abet them and enable the deaths of thousands more Americans by allowing them to keep their jobs.

So there’s hope — and it comes on November 3.

Until then, we have dogs, and The Beatles.

October 4th, 2020

Does the White House Outbreak Invalidate the Strategy of Frequent Testing for COVID-19 Control?

As I’ve written here many times, I’m hopeful that frequent, inexpensive, rapid home testing for COVID-19 will help us climb out of this pandemic mess.

Let’s name it the Mina Frequent Testing Plan, after my indefatigable colleague Dr. Michael Mina who has championed it for months — most recently in a perspective published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

For the Rip Van Winkles out there, here are the basics of this approach:

- Much of the community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 comes from people who don’t know they are infectious since they have no or few symptoms.

- Testing them using standard PCR tests is impractical — too slow, expensive, and difficult to access.

- Scientists and companies have collaborated to develop simple paper-based rapid tests done on saliva samples.

- Results return in 15-30 minutes and require no special instruments for interpretation — analogous to home pregnancy or HIV tests.

- Produced at scale, the tests are cheap and readily available — $1-5 each.

- These tests pick up some people who have high levels of infectious virus but are either asymptomatic or presymptomatic — hence potentially contagious to others but otherwise unaware themselves. Now, none of these people are being detected.

- Once they have a positive test, they isolate at home — they don’t go to work or school. Tests would be confirmed using standard PCR.

- Individuals can also buy them for use at home.

- Schools, hospitals, nursing homes, food service companies, places of worship, and others can purchase them in bulk, with requirements for a negative test (even better, a series of negative tests over the previous several days) for entry.

The strategy has a growing number of advocates across the medical, scientific, and public health fields — including the FDA — which is exciting. Here’s a short white paper on the topic many of us have helped draft, with a focus on testing in schools.

But as the Mina Frequent Testing Plan drew sufficient attention, various criticisms appeared, in the press and on social media. (Here’s a skillful rebuttal.)

These negative views certainly raise important concerns. I worry in particular about false positives — they will be inevitable when doing high-volume testing on a low-prevalence population.

Now, we have a president who acquired COVID-19 despite the fact that he and those who surround him are tested often.

How did this happen? Is this the death knell of the Mina Frequent Testing Plan?

The obvious first explanation is that no test is perfect. The rapid antigen tests used by the White House will miss some people who are infectious. Of particular concern are those who get tested only once, right before meeting the president.

The math is simple — if you increase the number of visitors, you increase the chance that at least one person with infection will escape detection with a single rapid test.

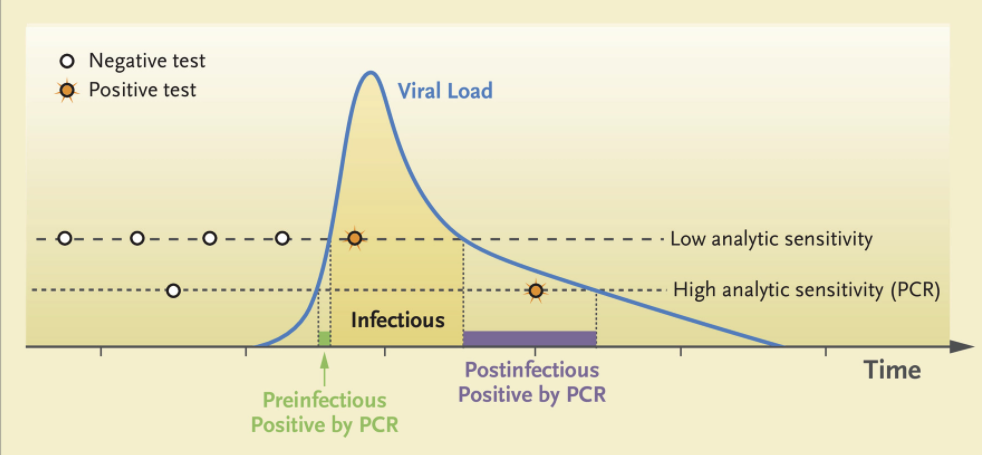

Remember, one strength of the Mina Frequent Testing Plan is just that — it’s frequent! People who test negative in the early phase of infection will test positive with tomorrow’s or the next day’s test based on the kinetics of viral replication in someone who has just come down with the disease.

From Mina’s NEJM piece, here are those viral trajectories — a person with a negative test in the morning could potentially be infectious shortly thereafter:

With the many visitors to the White House on Saturday, September 26 — the day the president announced the nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court — only a single rapid test granted them access to the event, mask-free.

Also, let’s remember that testing won’t give us a free pass to behave as if we were living in the Before Times, again because testing isn’t perfect. Certain activities facilitate spread of the virus — crowds, close conversations, poor ventilation.

How about this for an example?

At least 7 people who attended ACB's nomination ceremony in the Rose Garden on Sep. 26 have since tested positive for coronavirus. But experts say the more risky time spent that day was at a reception inside the White House. Here are some scenes. https://t.co/mTsZsxmSfy

— Christiaan Triebert (@trbrtc) October 3, 2020

Ouch.

Or this?

Double ouch! Watching that video makes most of us ID clinicians feel like we’re living on another planet. Suspect many of you readers feel the same!

In summary, let me quote my Boston ID colleague Dr. Roby Bhattacharyya, who wisely wrote:

People tap-dancing prematurely on the grave of rapid testing should reflect on how remarkable it is that for people behaving this way all year, indoors and out, in a place with countless thousands of visitors, it took until October for a superspreading event to happen. Test more.

So yes, the Mina Frequent Testing plan lives on — even if the track record of keeping the president free of the virus does not.

Which teaches us more about the limits and vagaries of human behavior than it does the limits of testing, doesn’t it?

September 27th, 2020

Humbled — But Still Hopeful

When Dr. Anthony Fauci joined us earlier this month for a virtual medical grand rounds, several of my colleagues participated. At the end, each was asked to comment about what they had learned so far from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. Michael Klompas, our brilliant hospital epidemiologist, wisely answered:

Humility.

His answer resonated strongly again, because this week our hospital is facing a cluster of cases on our inpatient service.

I want to underscore that Mike and our infection control team have worked tirelessly on our COVID-19 response right from the first moment we heard about it in January — longer than anyone. They have done an exemplary job, providing transparent and evidenced-based guidance. They have done everything they can to keep our patients safe, and bring us to work safely as well.

The clinical staff — doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, physical therapists, social workers, dieticians — adhere to infection control policies. Same for other essential workers delivering food, cleaning the rooms, working in the cafeteria, transporting patients.

But we humans are, well, human. Meaning not perfect. Nor are systems created by humans perfect. We are constantly learning. To pretend otherwise would be hubris.

And our cluster is a reminder that this is a tricky virus. As some have said, the Goldilocks’ porridge of viruses when it comes to how it spreads.

Not so universally severe that it can be diagnosed and contained once identified — like Ebola, SARS, MERS.

Not so well-understood from a transmission perspective that cases can be prevented through avoiding exposures and targeted immunization — rabies.

Not so mild in most people that we can tolerate nearly universal infection — Epstein-Barr virus.

To cause a pandemic, the likes of which we haven’t seen in over a century, SARS-CoV-2 has to be just right.

It causes a mild infection in most (not all) young people; becomes progressively more serious as we age; takes advantage of those with common comorbidities (diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity); and — here is the crucial factor — spreads to others before we have symptoms.

Or even have no symptoms at all.

Now, as the hospital tests literally thousands of employees, sequences the virus, does engineering analyses, and conducts behavioral interviews, we’ll optimally learn what happened with this cluster so we can prevent it from happening again — both here and elsewhere.

Yes, humbled. But optimistic that with continued transparency about what we find, there will be progress.

September 20th, 2020

Sports During COVID-19 — When What Doesn’t Matter Actually Matters a Lot

A few weeks ago, I got a text from a long-time ID colleague here in Boston:

Hey Paul want ur opinion … this is for an interview with MLB radio, and no one knows less about baseball than I do, but as an avid fan and wise ID doc, do you think the season should continue?

Confession — it took me around 3 milliseconds to respond, if that.

And my answer was yes.

But, some no doubt are thinking, we’re in the middle of a pandemic. It’s hardly under control. A bunch of players had already tested positive, proving it’s not safe.

And — let’s remember — it’s just sports. Sports don’t matter.

But here, in all its tarnished, selfish, complicated, and ultimately messy way, is why I still think it’s worth trying to play professional sports in 2020.

These professional leagues have extraordinary resources — and the motivation — to control outbreaks. The NFL alone boasts annual revenues of $25 billion. You think this might motivate the owners to play the games safely?

The players’ careers don’t last forever. The average professional football player’s career length is only 3-4 years, Major League Baseball 5-6 years. That’s the brief time most of these supremely talented individuals make the bulk of their life’s earnings.

The slowed reflexes, loss of muscle strength, decreased vision, accumulating injuries, and other changes brought on by aging loom as opponents that no athlete has ever beaten. A fast, hungry young rookie is always coming up to take their place — especially if they’re not superstars.

The clock ticks down on these brief careers even during a pandemic.

Sports have already taught us something about disease control — and can teach us more. With coordination well beyond what our government appears willing, motivated, or capable of doing, they have deployed extraordinary strategies that, so far, have been remarkably effective.

Can anything be more of a success story than the NBA? Who could have predicted that they would have zero COVID-19 cases when they placed hundreds of young men into Florida during a surge of cases?

Their strategy of frequent testing, creating a limited “bubble” of exposures, and importantly getting buy-in from both the ownership and the players now is being emulated by other industries.

Not only that, they helped validate a new technique for using saliva for COVID-19 testing.

I’ve made no secret that I don’t like football, and confess I prepared myself to reject whatever plan the NFL came up with to play the games safely. The decades of denials the NFL tossed out about the hazards of the sport gave me no confidence they could possibly go forward with a legitimate plan.

But no! After listening to this Freakonomics podcast, I was frankly blown away at their thoughtful and highly detailed approach. This includes frequent (daily!) testing, active participation of the players’ union and the league in civilized negotiations about policies, reliance on science rather than emotion or politics to do the right thing, wow — this is how to bring an epidemic under control!

Professional sports give many of us something we need right now — a distraction. Pandemic. Fires. Violence. Racial tension. The death of an inspirational public figure. Raging political discord.

Yep, 2020 has it all. Why not enjoy a few moments away from these nightmares to watch Naomi Osaka storm back and win the US Tennis Open, or LeBron James fight Father Time in the NBA playoffs, or Mike Trout continue a career that looks like he could become one of the greatest baseball players of all time?

With echoes of FDR’s advice to proceed with the baseball season despite World War II, again sports can give us a well-needed reprieve from the grind of daily existence, both as fans and as participants.

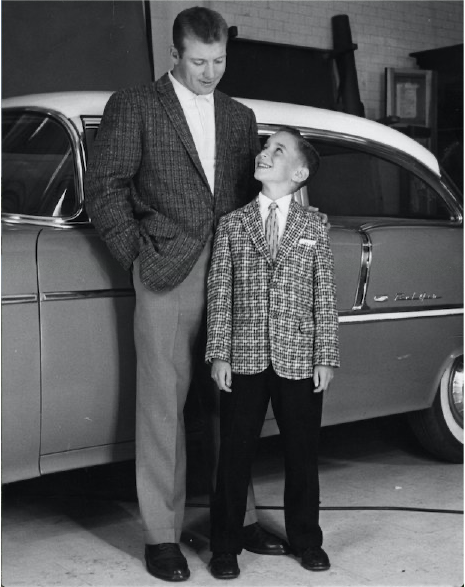

One of my patients, mostly very isolated since early March due to COVID-19, kindly shared the above picture with me since he knows we share a fondness for baseball. (Ok, “fondness” = obsession.)

It’s a promotional photo taken with Mickey Mantle in 1956, the year he (Mantle) won baseball’s Triple Crown. (I’m sharing it with my patient’s permission.) Take a look at that kid’s face! And thinking about sports still gives him pleasure today.

Some might argue that these professional leagues’ safety measures divert resources (especially testing) away from schools, nursing homes, and other settings that need them more. Fair enough.

But is there any indication that if pro sports didn’t start up again, that the tests would have flowed to the schools? As noted by Will Leitch, “All of us should be able to get tested easily and quickly! But that fact does not inherently mean that what leagues are doing is wrong.”

So let’s play ball — and hope we learn something from these professional leagues about how to control the pandemic by getting buy-in from all involved.

And, most importantly, by following the science.

September 13th, 2020

Restaurants Are Hurting — But Dining Indoors Poses Real COVID-19 Risk

As we learn more about transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the news for restaurants goes from bad to worse.

And while there’s a long list of sad things about this pandemic, the decimation of the restaurant business for owners and the people who work there is right up there. The loss of the restaurant experience for us diners is pretty sad, too.

Importantly, restaurant dining isn’t one of those hypothetical risks for COVID-19, such as surface contamination of groceries and delivered packages. It’s a real, well-documented concern with strong supporting evidence.

In a CDC study conducted at 11 healthcare facilities and just published last week, investigators queried 154 people with symptoms consistent with COVID-19 and positive tests, along with 160 control individuals testing negative. They asked about various activities in the two weeks prior to the onset of symptoms — eating out, shopping, going to an office, visiting a hair salon, taking public transportation, attending a religious service, and others.

People with positive test results were more than twice as likely to have reported dining at a restaurant than were those who tested negative. No other activity conferred significant risk.

It’s a small study, and the authors note several potential limitations, but they amplify the message that crowded settings, close contact, and lack of mask wearing indoors increase the risk of COVID-19.

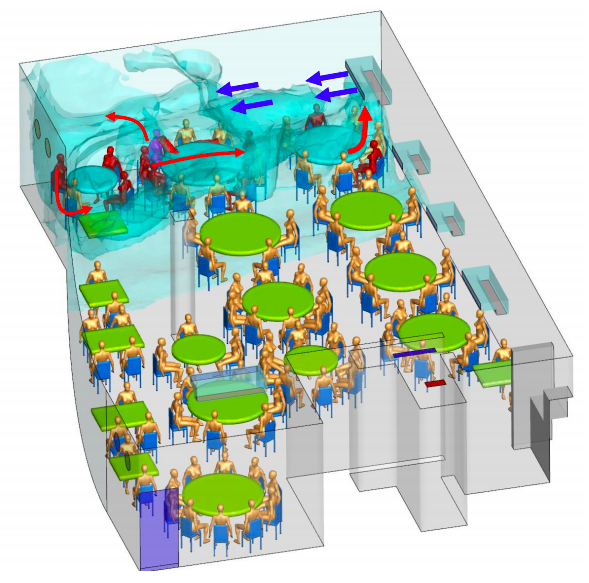

The vagaries of restaurant ventilation — so exquisitely detailed in this investigation of a restaurant outbreak in China — add to the hazards of indoor dining.

Here, one presymptomatic person infected nine other diners, all of whom sat under the the same air conditioning vent that recirculated “old” rather than fresh air.

None of the 68 diners in other areas developed COVID-19, nor did any of the 8 waiters — likely because transient contact is much lower risk.

Meanwhile, Harvard epidemiologist Professor Miguel Hernan compares epidemic curves in New York and Madrid in this fascinating thread:

1/

Look at the shape of these curves.New York and Madrid had similar epidemics until they spectacularly diverged.

In March, both cities were caught by surprise and shut down because of #COVID19.

In September, the situation is under control in NY and alarming in Madrid.

Why? pic.twitter.com/VF0BCl0xyt

— Miguel Hernán (@_MiguelHernan) September 11, 2020

What does this have to do with restaurants?

In New York, indoor dining is CLOSED. Indoor dining in Madrid was OPEN at 60% capacity in June. Bar service opened too. Protocols weren’t aggressively enforced. Since June it has been easy to find crowded bars and tables. The contrast with NY was striking as anyone spending time in both places can tell you.

Is it too far fetched to extrapolate from these cross-city comparisons and conclude that opening restaurants played a role? Not really, when you consider how cases in the southern US spiked when bars and restaurants opened in regions that still had significant community transmission.

(And having had the pleasure of dining late — and I mean late — into the evening in Madrid, I can assure you that these meals are the very opposite of transient when it comes to potential exposure time.)

As noted above, all this information about restaurants and COVID-19 risk makes me very sad. Having grown up in New York — arguably one of the world’s great restaurant cities — I love the way a top restaurant experience provides more than just excellent food. The atmosphere, the conversational buzz, the decor, the rituals, and of course the intermingling of so many different cultures enhance our lives in countless ways. Certainly I’m not alone in missing this colorful aspect of life from the Before Times.

Not only that, but my mother worked as a food writer, and for years wrote a weekly column in the New York Daily News on hidden restaurant gems in the city. If a new Ecuadorian restaurant opened in Queens that generated some buzz, you can be sure we’d soon be sampling some empanadas ecuatorianas or llapingachos.

Meanwhile, awaiting a vaccine and other preventive strategies, what can we do now to support these hurting restaurants?

Dine outside while we can. Tip heavily. Order take out. Buy merchandise. Other ideas here.

But skip the indoor dining in restaurants for now. And while we miss it, it might help to remember that eating out isn’t always so great.

https://youtu.be/K_q4S7lZeik