An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

December 30th, 2021

Omicron and Reduced Severity of COVID-19 — Some Good News We Desperately Need

We’ve been burned so many times making predictions about COVID-19 that I should post this conspicuously by my computer:

The famous pundit meant, of course, that “you don’t know anything” — we know his true intentions since he also said “Nobody goes there anymore. It’s too crowded.”

The “know nothing” quotation is a reminder that COVID-19 is a new disease. While we do in fact know more than nothing, we still have so much to learn. This applies to pretty much the whole COVID-19 universe, including its origins, virology, immunology, epidemiology, prevention, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and complications. Constantly learning, constantly updating assumptions, guidelines, and messages.

With that humble start, I’m about to write a sentence that fills me both with excitement and, I confess, some trepidation.

It looks like Omicron causes less severe disease than prior variants.

Why trepidation? Well obviously I don’t want to jinx it, we’re still in the midst of a very major surge.

As anyone with a pulse knows, a lot of people have been diagnosed with COVID-19 in the past few weeks, more than we’ve seen at any point in the pandemic.

In fact, our world right now is a mess. (I’ve gone back and emphasized this sentence with bolding and italics, as some readers have told me they missed my acknowledging this stark truth.) Some have a mild or asymptomatic case, but some are miserably ill, recuperating at home. A smaller number are hospitalized with severe COVID-19, especially the unvaccinated or those with impaired immune systems. Some proportion of all these cases could end up with long COVID, a dreaded complication with still no clear treatment.

Plus, each new diagnosis — regardless of severity — enormously disrupts family, school, work, and social life. What I’m about to write does not in any way to diminish how awful the pandemic is right now for just about everyone.

But looking at the evidence and clinical experience on severity, I’m going to poke the beast and conclude that Omicron does appear milder.

First, the big picture — we have a record number of cases pretty much everywhere in North America and Europe.

(1) The massive number of infections in European countries is "real".

Yes, more people got tested for Christmas, and there have been some backlog issues in many countries.

But the 7-day positive rates have been rising rapidly, and nothing indicates that cases are "over-counted". pic.twitter.com/YFClWuXDYa— Edouard Mathieu (@redouad) December 29, 2021

However, despite this extraordinary spike in cases, deaths from COVID-19 are numerically lower than they have been at any point since way back in October 2020, more than a year ago. Record high case numbers and fewer deaths means that the global case fatality rate has dropped — it’s now below 1% for the very first time during the pandemic.

It’s even more encouraging when you consider that we are undoubtedly undercounting cases, both because people with mild symptoms are less likely to be tested, and because positive home tests are rarely reported. That denominator keeps getting bigger.

What these remarkable data tell us is that Omicron’s mutations may fool our antibodies, but our protection is far from useless — infection with Omicron occurs, but our primed cellular immunity (from prior infection or vaccines or both) quickly kicks in and takes it out. Go T-cells!

Second, let’s look at Omicron — the virus itself — in the lab, and compare it with other variants in its ability to inflict damage on various cells. Soon after Omicron appeared, a lab in Hong Kong reported that it grew less well in lung tissue than other variants.

Just one lab? Interesting, but let’s see what others find … and now we have no fewer than four others all reporting similar data, a veritable world tour that started in Hong Kong, but now includes Liverpool, Belgium, Japan, and Cambridge:

5 Studies, 5 Figures. All consistent, independent replications in vivo, in vitro. Omicron can't infect lungs or lung cells as well as prior variants.@KU_Leuven @SystemsVirology @GuptaR_lab @hkumed @LivUni pic.twitter.com/X9jbugx0vs

— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) December 29, 2021

Less virus activity in the lung could mean less lung damage, the primary organ targeted in severe — and fatal — COVID-19. Hope.

Third, let’s talk with the front-line clinicians — people like you and me. The doctors and nurses seeing cases in South Africa told us repeatedly in late November that this Omicron-related COVID-19 was different, that patients were less sick.

They generated data to confirm their impressions, yet somehow some northern hemisphere docs still didn’t buy it.

South Africa just had a devastating Delta surge, the thinking went, so there was natural immunity protecting them — the lower severity may not apply here. And remember, it’s summer down there. Plus, can the data be trusted if not collected here?

But now, our data and our anecdotal impressions match theirs — in plain speak, they were right. Anyone doing clinical care currently in the United States would agree that most cases we see right now are truly mild.

Not just mild in the over-inclusive category of “not requiring hospital care.” But mild like any generic endemic respiratory bug — remember those? Many of the clinical encounters with patients with COVID-19 occur over the telephone, and even their voice sounds different from prior variants — stronger, more confident they’ll recover, less afraid. That’s highly anecdotal, I know, but it’s just what I’m hearing.

So what does this giant Omicron surge, with a seemingly less-dangerous variant, mean for the future of COVID-19?

What does it mean for the “average” patient who gets it? How about for the immunocompromised, the elderly? For young children?

What does it mean for the logistics of patient care, work, schooling, getting together with friends and family, or just trying to live our lives in some tolerable way until the surge abates?

What should it mean from a policy or public health perspective?

What do these early data on cross-immunity with Delta mean? Sounds promising, but what does it mean for protection against future surges, or the inevitable next variant?

I could speculate, both on the optimistic and pessimistic side.

But I don’t know nothing.

Happy New Year, folks.

December 20th, 2021

Believe It or Not, We Already Have a Highly Effective Outpatient Antiviral Treatment for COVID-19

A pine tree. With a colorful birdhouse.

And that treatment is … (drum roll) … remdesivir.

Yes, you heard me right. Remdesivir, the very same antiviral with a checkered history in COVID-19 clinical trials, with some studies showing efficacy (sort of), others not much of anything.

What’s the truth here?

For that, let’s turn to what gets my vote for the most unheralded highly favorable clinical trial result since the start of the pandemic, the PINETREE study.

The trial randomized 562 outpatients with an increased risk for severe COVID-19 to daily intravenous remdesivir for 3 days or placebo. None had vaccination or treatment with monoclonal antibodies.

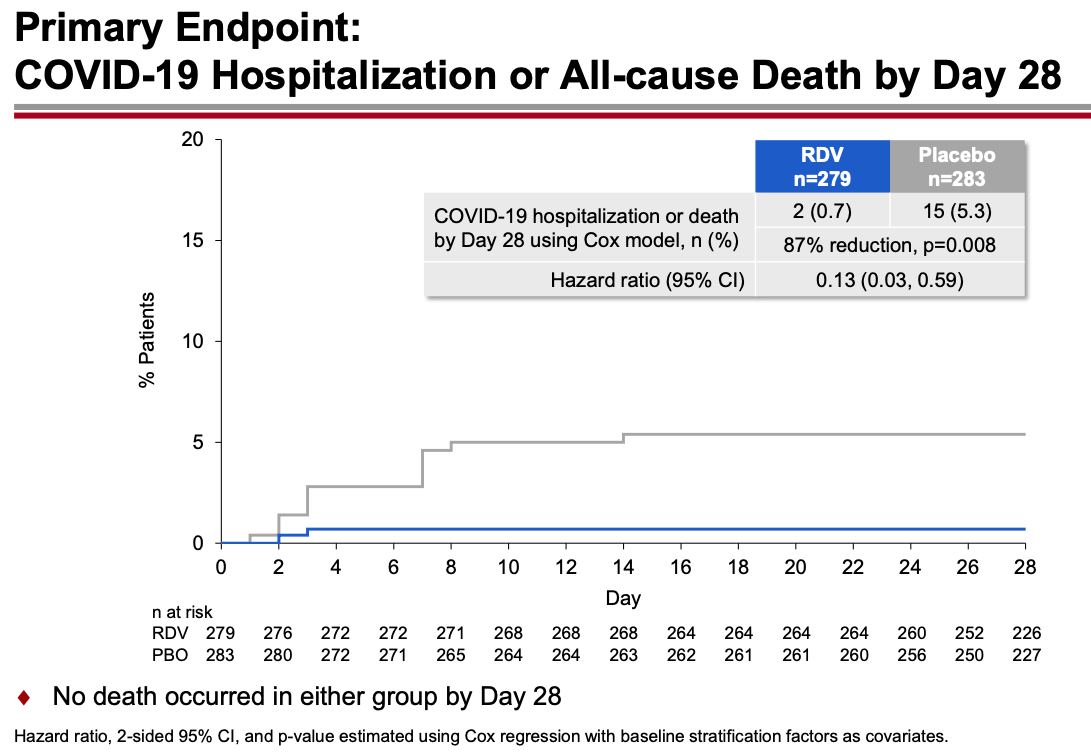

The results were unequivocally positive — remdesivir-treated patients had an 87% reduction in the risk of hospitalization or death, with no significant treatment-related toxicities. Key figure from the IDWeek 2021 late breaker presentation:

The contrast with the so-so results of the drug in hospitalized patients is striking, and underscores the importance of early antiviral treatment for this disease. By the time the immune-mediated organ damage kicks in — which is when most hospitalizations take place — it’s often too late for antivirals to have any effect.

Note that remdesivir given early in the course of illness to outpatients yields comparable results to the monoclonal antibodies and nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir (Paxlovid), and better results than molnupiravir. (Yes, caveats about cross-study comparisons understood.) Furthermore, remdesivir has been available for months, and is the only fully FDA-approved treatment for COVID-19 — which means clinicians can prescribe it in whatever setting they deem useful.

But it’s hard — OK, nearly impossible — to find anyone who has actually used remdesivir in a nonhospitalized patient:

The PINETREE study showed that remdesivir daily for 3 days in nonhospitalized, high-risk individual with Covid19 reduced the risk of hospitalization by 87%.

Have you or anyone you know used it this way outside of a research study? https://t.co/o9e0IBPH0F— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) December 19, 2021

The reasons so few have adopted this treatment are obvious. Setting up outpatient intravenous therapy urgently is a challenge even under the best of circumstances — and doing so for patients who are acutely ill and have a highly contagious infectious disease only makes it more challenging.

The study sponsors recognized these hurdles and stopped the study early because of the availability of single-infusion monoclonal treatment and vaccine availability, both of which seemed destined to make the study results of limited clinical utility.

But with Omicron’s arrival, the results of PINETREE instantly become quite relevant. Omicron is so highly contagious and vaccine evasive that many people who have been “fully vaccinated” (time to retire that phrase, by the way) will contract COVID-19. My (very funny) British ID colleague Neil Stone describes it as follows:

Forget airborne, this thing seems to spread by telepathy — feels like you can catch it just by THINKING about it.

Furthermore, the most widely used monoclonal antibodies in current use — casirivimab and imdevimab and bamlanivimab and etesevimab — don’t neutralize Omicron. Sotrovimab, which is predicted to retain some activity, is in very short supply. The oral antivirals nirmatrelvir and molnupiravir are not yet available, and even once they get approved, supplies will be severely limited. Note again that molnupiravir reported lower efficacy than remdesivir, and furthermore has mutagenesis concerns.

My late colleague Francisco Marty — a brilliant clinical researcher — proposed studying remdesivir as a single IV dose, analogous to the one-dose baloxavir and peramivir treatments for influenza. This would greatly facilitate outpatient and emergency room treatment. Remdesivir infusions don’t take long, and require no post-treatment observation. Unfortunately, the study never went forward.

Maybe it’s time to revive the idea? Start a clinical trial now comparing 1 vs. 3 doses, using a noninferiority design?

Regardless, we’re going see a lot of COVID-19 in the next few weeks. Since most PCR assays do not report “spike gene target failure” — a hallmark of Omicron — clinicians will not know in real time whether these cases are Omicron or Delta, and hence whether the currently available monoclonal antibodies will work.

But based on other regions where Omicron appeared, the dominance of this variant is all but inevitable and will occur rapidly. This experience in Houston is typical, one we’re seeing in multiple areas in the United States right now:

Sunday Update: The Omicron variant is now in Houston in full force, accounting for 82% of new symptomatic Houston Methodist #COVID-19 cases as of earlier this week.

#Omicron became the cause of the supermajority of new Houston Methodist cases in less than three weeks. pic.twitter.com/XL5C31P4As— S. Wesley Long (@drswlong) December 19, 2021

Why not prepare for this change by shifting the resources we’ve developed for intravenous monoclonal antibodies to intravenous remdesivir? Let’s offer this first to our highest risk patients — people who are B-cell depleted, transplant recipients, other severely immunocompromised.

It won’t be easy, but it will be worth it. Let’s use all the effective tools we have to treat this disease, and that includes remdesivir for high-risk outpatients.

December 15th, 2021

Do We Need to Remind People that COVID-19 Is Truly Awful?

Last month, I read a deeply harrowing description of what it’s like to be hospitalized with severe COVID-19. I strongly urge you to read the full thread:

https://twitter.com/CRStoli/status/1458600993621430272?s=20&t=km6XxJ5IDsQGQKsygjXfWg

Something about the plain, direct language he uses to describe the patient experience hits home here like few other depictions I’ve read — it rings true in so many ways.

And many of us in healthcare might forget just how dehumanizing and uncomfortable hospitalization can be — not just the severe discomfort of being critically ill, but the added insults of daily early AM blood draws, terrible food, scratchy pillows, and loss of privacy.

Peter in the captain’s chair.

The author is Chris Stolarski, associate director of university communication at Marquette University in Milwaukee, who was kind enough to talk with me further on an OFID podcast, which is also embedded at the bottom of this post. You can tell from our chat that Stoli (that’s what everyone calls him) is by nature an upbeat person — a Groucho Marx fan and music lover, with a particular fondness for old dachshunds. Here’s his pup Peter, by the way.

Still, Stoli is quite clear that he nearly died — his hospitalization was a terrifying nightmare, and his recovery far from easy, the illness leaving him with permanent nerve damage and tachycardia. He’s hopeful that telling his story will convince more people to take COVID-19 seriously and get vaccinated. (He contracted COVID-19 before vaccines were available.)

Why is this still important? Well just this week, The Atlantic published a piece entitled, Where I Live, No One Cares About COVID, by Matthew Walther.

In a bemused, and at times openly mocking tone, he cites the ongoing concerns about COVID-19 as the domain of the coastal, urban elites. For him and his family, living in rural Michigan, life has been back to pre-pandemic normal for nearly two years.

Here’s a typical passage, in which he openly ridicules media coverage of how to gather safely during the holiday season:

As Christmas approaches, we can look forward to more of this sort of thing, with the meta-ethical speculation advanced to an impossibly baroque stage of development. Is it okay for our 2-year-old son to hug Grandma at a Christmas party if she received her booster only a few days ago? Should the toddler wear a mask except when he is slopping mashed potatoes all over his booster seat? Our oldest finally attended her first (masked) sleepover with other fully vaccinated 10-year-olds, but one of them had a sibling test positive at day care. Should she stay home or wear a face shield? What about Omicron?

I don’t know how to put this in a way that will not make me sound flippant: No one cares.

Yes, he’s an excellent writer. Also yes, he’s deeply wrong about this last sentence — No one cares should more accurately really read, I don’t care. Otherwise, he’s guilty of the same echo-chamber bias he’s leveling at “the professional and managerial classes in a handful of major metropolitan areas.”

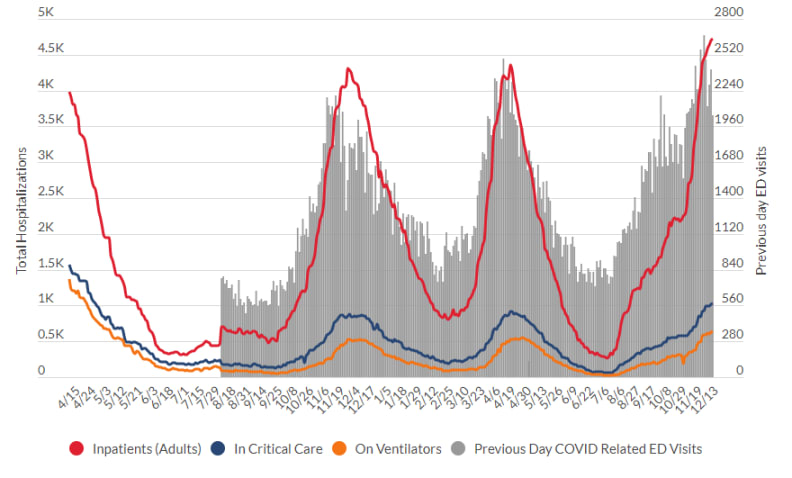

Readers of this site will no doubt be aware that Walther chose to write this piece as cases and hospitalizations due to COVID-19 continue to increase rapidly in most of the United States — including in Walther’s state of Michigan:

Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services

We’re sadly on the same grim trajectory we were last winter — and this is before the highly transmissible Omicron variant makes a major push into our country. We might deeply want COVID-19 to be over, but this doesn’t magically make it happen — the virus couldn’t care less.

Not surprisingly, Walther’s piece triggered the ire of many (raises hand!), in particular front-line healthcare workers who can’t hide from the disease. Here’s a particularly good (and angry) commentary from University of Colorado’s Dr. Josh Barocas, who kindly substituted * for certain letters so I could quote it here on these pages:

As an ID physician, frontline worker, & public health professional, I think I’ve generally held my sh*t together pretty well over the past two years (not lashing out, being civil) but this garbage @TheAtlantic article undid me (let me explain)-please readhttps://t.co/oWyLwtKmcj

— Josh Barocas, MD (@jabarocas) December 14, 2021

Well said, Josh. Because the answer to the question posed by title of this post is clearly YES.

(Transcript here.)

December 13th, 2021

ID Learning Units from Inpatient ID Consults

Nerve cells in a dog’s olfactory bulb, from Camillo Golgi’s Sulla fina anatomia degli organi centrali del sistema nervoso (1885).

Need a break from all-things COVID-19? Feeling OH-verwhelmed by OH-muh-kron?

(I guess that’s how some pronounce it … or AWE-mee-kron… or oh-MIKE-ron … or who knows. Two things for sure — there’s no “n” after the “m”, and it’s a drag regardless of how it’s pronounced.)

To cheer everyone up, here’s a palate cleanser of non-COVID-19 ID Learning Units from a stretch on the inpatient ID service earlier in the fall. I’ve been storing them up just for today.

Here are the criteria for inclusion:

- Has to be related to a case.

- Has to be posted each consecutive day. (Careful readers will note I missed one so did two on one day. Mea culpa.)

- Has to have a reference.

- Has to be interesting.

- Has to have no patient confidentiality issues.

And for this batch, it has to be a non-COVID-19 topic. Though some may find it hard to believe, there are other infectious diseases out there — in fact the entire field of ID existed before SARS-CoV-2 ever jumped its way to humans and started this dismal pandemic.

As always when on service, I’m very grateful to have worked with a couple of highly energetic and smart ID fellows, an ID pharmacy team (faculty and resident) who taught me something daily, plus a medical resident who seems destined (I hope) to be a great future ID doc.

Hooray for that!

Off we go, each with a bit of commentary about why they were selected:

#1:

Day #1: NADIA trial — after rx failure, DTG non-inferior to DRV/r when given with either TDF/3TC or ZDV/3TC, despite *extensive* NRTI resistance. Huge implications for management of both viremic and suppressed patients. https://t.co/Mjx6EWoH4J

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 13, 2021

NADIA is one of the most practice-changing studies in HIV medicine in a while — which ironically will be more relevant in clinical practice for those already suppressed than those with treatment failure, even though the latter is the study population.

Key question — can essentially all people with HIV on 3-class regimens or NRTIs plus boosted PIs due to resistance switch to tenofovir/FTC plus DTG? Or even simpler, to BIC/FTC/TAF? I think so, provided they have full susceptibility to INSTIs.

#2:

Day #2: Xpert MTB/RIF outperforms AFB smear in ruling out TB in low prevalence settings, with two negatives having a 100% neg predictive value. An important advance in hospital infection control. @annieluet https://t.co/zR5cxxTMQk pic.twitter.com/NEUY2I4XLN

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 14, 2021

The results of this study greatly expedite the tuberculosis rule-out, which in low-prevalence settings is done on many patients with an extremely low pre-test probability of TB. As always, no test is 100% perfect in the real-world setting, which means that for high pre-test probability cases, we might need to keep up precautions even with negative testing.

#3:

Day #3: For pts with recurrent cellulitis, this RCT showed that penicillin reduced the incidence of cellulitis from 37% to 22% over a median of 25 months of follow-up. NNT to prevent 1 episode of 5. Practice-changing study for many clinicians. https://t.co/b27R12pP3D

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 15, 2021

I find myself citing this study repeatedly, probably because there are so few clinical trials of long-term antibiotic use that so clearly demonstrate benefit. And don’t forget the compression stockings, another effective measure!

#4:

Day #4: Small comparative clinical trial found T/S as effective as sulfa-pyr for toxo encephalitis, and better tolerated. Results reinforced by observational data and clinical experience globally. Often we switch to T/S at d/c — what's your practice? https://t.co/6mI3yiCZxg pic.twitter.com/KObKFzabTJ

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 16, 2021

This is the only randomized trial comparing TMP/SMX to pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine for HIV-related cerebral toxoplasmosis, and it’s woefully underpowered (a fancy way of saying, “too small”). But globally many more use TMP/SMX for this infection — it’s more readily available, less expensive, and much easer for patients to take.

Since it’s highly doubtful that there ever will be another controlled clinical trial, at what point do guidelines shift to recommend TMP/SMX over pyrimethamine-sulfa solely on the weight of clinical experience? I’d vote soon, since it’s not as if the pyrimethamine-sulfa strategy itself was ever subject to a controlled studies. (And no, I don’t know why this 1998 study was reprinted in December 2020.)

#5:

Day #5: The Staph intermedius group includes several coag pos staph spp that are the predominant cause of soft tissue infection in dogs — but can rarely also cause invasive disease in humans. Woof https://t.co/qCvwTlZcdI @NeilanAnne pic.twitter.com/wZ6aPGPKpY

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 17, 2021

Hi Louie! A self-indulgent post about a little known dog-related fact.

#6:

Day #6: Cefepime neurotoxicity is most common in older patients with renal dysfunction (heard that one before?), and should be considered especially in those with myoclonus. Don't forget dose adjustment in renal disease! https://t.co/Rl9Wcm6Gwd pic.twitter.com/JEbqlOBGqz

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 18, 2021

Anecdotal impression: Among hospital-based clinicians (hospitalists and medical residents), there is much greater awareness of this notable adverse effect of cefepime — especially with the decline in use of vancomycin plus piperacillin-tazobactam due to concerns about its renal toxicity.

#7:

Day #7: S maltophilia is intrinsically resistant to many agents (n.b. carbapenems), but often retains susceptibility to T/S, levo, ceftaz, mino. T/S usually listed as Rx of choice, but no comparative studies. Meta-analysis: FQ at least as good as T/S. https://t.co/4Rd48eNzDq pic.twitter.com/HH29KqOX0a

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 19, 2021

“Steno” is such a tough bug to treat, and TMP/SMX at high dose can’t be used for everyone. Spoiler alert — another good observational study on TMP/SMX vs levofloxacin about to be published soon in a journal near you.

#8:

Day #8: Cefiderocol enters bacterial cells using active iron transporters & is active against many MDR GNR. C/w best available Rx, cefiderocol similar to best therapy vs CRE, but w/ numerically more deaths — cause unclear. Chance due to small #'s? Other?https://t.co/s7pOmv0rb3 pic.twitter.com/kpenANJZsR

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 20, 2021

This is one of those inexplicable clinical trials, with an important outcome — deaths! — happening more in the experimental cefiderocol than the control arm, for reasons that still are not clear. (Reminds me of the early clinical trials of bedaquiline.) I suspect it’s because the heterogeneity of the patients with these infections is so huge that there’s the chance of death for multiple noninfectious reasons too, but I don’t know. For now, as we await more data, cefiderocol is increasingly used for treatment of highly resistant gram-negative infections in the hospital.

#9:

Day #9: How quickly can antibiotics turn blood cultures negative? Fast! The rate of pos blood cultures reduced by >50% just an hour after IV antibiotic Rx — but many will still be positive, so getting cultures in septic pts still useful. https://t.co/XOywNPd5Ob pic.twitter.com/xOP4mmI960

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 21, 2021

Reminder to emergency room, primary care, and urgent care clinicians everywhere — get blood cultures before starting antibiotics. Thank you very much, you’ve just made a lot of ID doctors very happy.

#10:

Day #10: Can we use cefazolin for treatment of central nervous system infections due to MSSA? Good concise summary of the data, pro and con, here. h/t @BWDionne https://t.co/VskwYvLi3Z pic.twitter.com/RJikvkJFrr

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 22, 2021

This particular question — can we use cefazolin over oxacillin or nafcillin for CNS infections due to MSSA — comes up all the time. The short answer is probably yes, with the bad reputation of cefazolin for this indication likely a carry-over from observations about another first-generation cephalosporin, cephalothin.

#11:

Day #11: In RCT of linezolid vs vanco for MRSA pneumonia, clinical response (PP analysis) was significantly higher with linezolid. Similar results in the ZEPHyR study (2013). Both had methodological issues, but data suggest it's as least as good. https://t.co/LXWc5m20op pic.twitter.com/2DNUkC6Gc8

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 23, 2021

Back when linezolid was a branded antimicrobial and cost a ton, many didn’t believe this company-sponsored clinical trial, discounting the results on various methodologic issues.

However, a second study found the same result (linezolid better than vancomycin), and hence this is one recommendation I frequently make when consulted on a case of MRSA pneumonia — switch the vancomycin to linezolid.

#12:

Day #12: Chemoprophylaxis is recommended for close contacts of patients with meningococcal infection. How about exposure to culture-positive respiratory secretions, e.g. from pneumonia or pharyngitis? CDC says no — interesting distinction. https://t.co/yrVwU6NSTZ pic.twitter.com/vpBAte42Dy

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 25, 2021

Since I don’t really understand this difference in recommendations for preventive therapy, allow me to quote Dr. Patrick Hickey: “Meningococcus is one of those infections for which every time there is a possible exposure physicians dutifully review the guidelines and then (more often than not) don’t follow them.” Agree!

#13:

Day #13: Impaired renal function is a risk factor linezolid-related thrombocytopenia. According to @BWDionne, we may one day see recommendations for reduced dosing (600 mg daily?) in patients with low eGFR. https://t.co/gYYygjmvXi pic.twitter.com/OQD0jNZo3p

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 26, 2021

More on linezolid! A reminder that impaired renal function is a risk factor for drug toxicity, which can be severe. Seems like dose reduction for this drug in some patients would be warranted, but is not now currently recommended.

#14:

Day #14: After suppression with boosted PI (bPI) plus NRTI as 2nd-line ART, maintenance Rx with bPI plus 3TC has high rates of success, even with M184V — better than bPI monoRx. One of many studies showing ongoing antiviral effect of 3TC even with M184V. https://t.co/kEVOaHLMHK pic.twitter.com/Cq30jbuBQq

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 26, 2021

Monotherapy studies with boosted PIs and dolutegravir have invariably failed despite their high resistance barrier, with more virologic rebound and development of resistance. As demonstrated in the NADIA trial (see #1, above), this can be overcome with just partial NRTI activity — which here in MOBIDIP is lamivudine despite the M184V mutation.

That’s a wrap! I’ll be on again over the holidays, will likely do the same.

Now enjoy this amazing visual (just a clip) of an extraordinarily beautiful piece — Un Sospiro (A Sigh), by Franz Liszt, played and displayed in a novel way. In dark times, it’s helpful to remember that human beings can do remarkable things.

https://twitter.com/YouTube/status/1350533338998693891?s=20

Plenty more where that come from!

December 6th, 2021

Omicron and the Quest for “Negative Capability”

John Keats, portrait by Joseph Severn

Wow, that was quite the depressing post-holiday week in ID Land.

For that, we can thank the new villainous variant, Omicron, which arrived ironically just as most of us here in the United States sat down to celebrate something approaching a “normal” Thanksgiving for the first time in two years.

Oh yes indeed, thank you very much for joining us, Omicron. How do you like your cranberry sauce?

Talk about an unwelcome guest at the party.

Here in Boston, like many parts of the northern U.S. and Europe, the arrival of Omicron joins a very active pandemic still dominated by Delta. It’s not like we needed this new highly transmissible, immune-evasive version of SARS-CoV-2 to jolt our holiday season. The current version (Delta) of the world’s least-favorite virus remains quite capable of straining hospital resources; disrupting school, work, and travel; and putting us all on edge.

Sigh.

Meanwhile, everyone wants to know what happens next. I totally get it — the pandemic has been with us for what feels like an eternity, and an accurate prediction would be highly valuable for all. Since the news broke about Omicron — has it really been less than 2 weeks? — these predictions have come in two vastly different flavors.

First the doom and gloom:

It’s highly transmissible … and very vaccine evasive … lots of reinfections … so many mutations … case rates skyrocketing in South Africa, fastest increase ever … super-spreader events among fully vaccinated … kids getting hospitalized … already it’s on all continents … some monoclonal antibodies won’t work … spike gene target failure, whatever that means … >30% test positivity in some parts of South Africa … transmission with minimal contact in Hong Kong … how do you even pronounce this stupid word …

Or alternatively, maybe it’s not so bad after all:

Cases are mostly mild … hospitalization rate is lower than with Delta … our cellular immunity (from vaccines or prior infection) will save us from severe disease … Omicron may have genetic material from common cold coronaviruses, and we live with those, don’t we? … maybe the mutations will make it less virulent … the vaccine manufacturers are tweaking the vaccines to respond … our PCRs and rapid antigen tests still work … some monoclonals (sotrovimab, AZD7442) should still be effective … antivirals are coming soon … this will be how the pandemic finally plays out, a mild disease leading to broad immunity …

So which one is it? Are we headed back to square one, and soon will be decontaminating our groceries and packages again? Or are we close to the pandemic endgame, optimistically predicted before, but this time we really mean it?

The reality is undoubtedly somewhere between these two extremes. We can’t possibly be going back to square one; we know so much about this virus by now:

I absolutely hate this title in @TheAtlantic

To say we know nothing completely neglects the research, learnings and experience of past 2 yrs.

We know SO much about Omicron.

Relative to ALL we DO KNOW, the things we don’t know are minor

— Michael Mina (@michaelmina_lab) December 4, 2021

On the other hand, Omicron could very well pose quite the challenge, as it appears to have qualities similar to Delta and has so many spike protein mutations that vaccine scientists gasped when they first saw the structure. In other words, beware overly optimistic predictions about Omicron just as much as doomsday scenarios.

Where does that leave us? At times of great uncertainty, I try to channel the teaching from a memorable college English literature course on Romantic poetry. (I know, pretentious — but stay with me on this one.) The great poet John Keats, writing to a friend, cited an ideal state of mind for the creative process, one he called “negative capability.”

Despite the word negative, he meant it in a quite positive way, as it describes a person “capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

Not surprisingly, I’m not the first person, and not even the first doctor, to think of this important quality while trying to navigate unknowns while living through a pandemic. Indiana University’s Dr. Richard Gunderman (who has way more titles than I) wrote earlier this year a highly pertinent essay:

Rather than coming to an immediate conclusion about an event, idea or person, Keats advises resting in doubt and continuing to pay attention and probe in order to understand it more completely … Negative capability also testifies to the importance of humility, which Keats described as a “capability of submission.” As Socrates indicates in Plato’s “Apology,” the people least likely to learn anything new are the ones who think they already know it all.

I’ve tried this negative capability approach this past week with the deluge of questions sent my way by worried colleagues, friends, and family.

Here’s a brief personal example, posted with permission:

Maybe it’s a copout, but for questions like this, there is no 100% correct, data-driven, or accurate answer. What would you say?

And how are you doing, folks?

November 23rd, 2021

Gratitude for 40 Years of Progress in HIV Care and Research

The Chap Book — Thanksgiving, Will H Bradley, 1895.

I was working with one of our outstanding senior ID fellows in clinic last week, and she presented the case she’d just seen, a 54-year-old man with HIV (certain details changed for confidentiality):

Will is doing great on [fill in one-pill daily regimen], missing no doses. He’s having some difficulty with sleep (his wife says he snores all night if he doesn’t use CPAP), not really sticking to his low-salt diet, and back pain. He agreed to get the flu shot. He’s due for labs.

In other words, this was your very typical HIV follow-up visit. Someone quite brilliantly likened them to well-baby visits for us ID doctors, because they often have zero active ID issues. It’s all about health maintenance.

(The flu shot doesn’t count as an active ID issue.)

Why even bring this up? Because this ID fellow had the wisdom to add, in an aside:

It’s hard to believe that just two years ago his CD4 cell count was 6, his viral load was over a million, and he was hospitalized with PCP.

Yes, it’s hard to believe. And it is amazing.

Remember, the median survival for a person like this with a serious HIV-related opportunistic infection in the 1980s was roughly 1 year. And today, this man not only has an excellent prognosis, but his active medical issues are the bread-and-butter of any primary care practice — sleep apnea, hypertension, low back pain, immunizations.

Thanksgiving is this week, and the best part of this holiday is that we express thanks for the good things that have come our way over the past year. In this spirit, I’ve typically written an ID-themed “gratitude” post in honor of this annual Thursday day off from work. It’s a fun column to write, and it’s interesting to look back and see the progress we’ve made and what we cheered about — especially in the pre-pandemic times. Sigh.

But this year, in honor of the 40th year since the publication of the first cases of AIDS, and because someone invited me to give a “History of HIV” talk, and because World AIDS Day just happens to be December 1, I’m going with just this biggie — the medical miracle of HIV care and research over the past 4 decades.

Here’s the talk I gave, Part 1, which covers the first twenty years:

The "History of HIV" talk I gave last week actually has this title, which I don't think is an overstatement. Posting it now with gratitude, just in time for Thanksgiving (my favorite holiday — the gratitude and family part).

(Part 1 thread)

1/x pic.twitter.com/120HGtFKEh— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) November 20, 2021

Part 2 is here, bringing us up to date, and finishing with a link to the full slide set — go ahead and download to your heart’s content. Both Parts 1 and 2 include content quite miraculous by any standards.

Grateful for this progress!

And grateful also for Saturday Night Live — a show which, despite its age, can still hit it out of the park* every so often.

Happy Thanksgiving!

*”Hit it out of the park”: To do or perform something extraordinarily well.

November 12th, 2021

Time to Simplify the COVID-19 Vaccine Policy — Authorize a Booster Dose for Anyone Who Wants One

Medlar, Poppy Anemone, and Pear. From The Model Book of Calligraphy (1561–1596).

At this point in the post-vaccine era of the pandemic, we all know people who have had COVID-19 despite being fully vaccinated. Patients, coworkers, family, friends.

The reason these breakthroughs are so common is now obvious — our initial vaccine strategies did not provide durable protection against infection. And recognition of this fact prompted the FDA and CDC to recommend a booster dose for people at high risk for severe COVID-19, and for people at high risk for exposure to the virus. Six months after the second dose is the recommended schedule.

Based on my occupation, I’m one such eligible person. (Thank you, Dr. Walensky.) But shouldn’t everyone have access to this benefit? I’d strongly argue yes.

Because at this point, it’s not just one study showing the vaccines are losing their effectiveness over time — it’s multiple studies, conducted all around the world in highly diverse settings and using different vaccines. As an example, let’s go with this large recently published paper because the effectiveness curves tell the story so clearly:

Important paper, just published @ScienceMagazine, on waning vaccine effectiveness among >780,000 US Veterans over time and during the Delta wave. Across all ages; J&J vaccine had the most decline; reduction protection vs deaths too (Figure at right) https://t.co/onRQY9XAl0 pic.twitter.com/nj6zG3Hedw

— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) November 4, 2021

While the vaccines continue to be way better than no vaccine in prevention of serious COVID-19, hospitalization, and death, they’re slowly losing their effectiveness in these metrics too — especially among high-risk individuals.

Let’s also state the obvious:

Some people who get “mild” breakthrough infections get pretty sick, and feel lousy.

They have fevers, chills, cough. They lose their sense of smell and taste. They are profoundly fatigued. They’re out of work, or school, and have to isolate from their family and friends.

In other words, though classified as “mild” cases for epidemiologic purposes, they don’t feel so mild to people who get them.

In addition, a symptomatic case — breakthrough or not — can pass the virus on to others, which is especially worrisome for the not insignificant proportion of the population who are immunocompromised and don’t get full protection from the vaccines.

Which is why, while watching our vaccine experts and public health officials and the FDA and the vaccine manufacturers debate over who should and who should not be eligible for a 3rd dose of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, I’ve come to the straightforward conclusion that it should be any adult who wants one.

And I’d recommend that strategy for pretty much 100% of people who ask me what they should do — just as I’d advise an annual flu shot. After all, influenza also causes a nasty respiratory viral infection that most of the time does not lead to hospitalization or death. We still want to prevent the flu in young healthy people, don’t we?

Another benefit of advising boosters for all is that it will simplify the messaging about what we advise our patients, which is now way too convoluted. Allow me to quote (with permission) primary care physician Dr. Lucy McBride, who expressed frustration with the conflicting messages she’s been getting from the press and the CDC. She wonders what to tell her booster-ineligible patients now:

My concern is over the messaging and about the lack of clarity from CDC about what our overall goals are. I think it would improve trust in our public health institutions if they just came out and said, “Look – the vaccines still work great in preventing hospitalization and death, but we are worried about rising case numbers in the upcoming winter months and would like to reduce infections as much as possible.”

Agree 100%.

Some worry that authorizing boosters for all locks us in to repeated cycles of COVID-19 vaccination in an endless cycle of shots. But the reality is we just don’t know enough yet to make this statement. It could be that just this third shot is required for durable protection in most people. Or, alternatively, that periodic boosters will be required. Or something in between, based on community risk of disease, age, other risk factors, or a simple test to assess who is protected and who isn’t, or some other metric.

In short, we just don’t know — best to acknowledge that up front.

Additionally, some argue that giving a third dose distracts us from getting the unvaccinated people their first dose, or that doing so depletes the vaccine supply from global distribution to places that have limited access, or that this will increase vaccine hesitancy, or that some very small fraction of those who get vaccinated will have an adverse event, or that there are other non-policy prevention strategies that need reinforcement.

These are legitimate points to raise (artfully done by colleagues of mine) in discussions about where to focus our efforts in public health. We should welcome these debates, but not lose sight of the fact that these efforts can be done in parallel. Continuing to advocate for first-time vaccination for the unvaccinated and simultaneously offering boosters to adults are not strategies that conflict. California and Colorado already have adopted this approach.

So as we head into the winter, with cases increasing again — and Europe providing a potential warning of what we’ll be seeing soon in the USA — it’s time to just make these third doses available to all who want them.

Because getting this viral infection stinks. And preventing it is in everyone’s best interest.

October 31st, 2021

Interesting and Important Studies from IAS 2021 and IDWeek That Caught My Eye

Vintage Halloween postcard, 1913.

As noted in my previous post, attending virtual meetings poses some serious challenges.

The biggest obstacle: trying to do one’s regular job while periodically checking in (or more likely not checking in) on the meeting. And while I might have been able to pull off some Really Rapid Reviews© after a few virtual meetings, not so for the last two.

So instead, I’ve packaged 2 into 1, hoping this gives you sufficient value for your blog-reading dollar, lack of really rapidness notwithstanding.

Here, then, are some highlights from these two meetings, in a not-so-rapid (but I hope still interesting) review. The International AIDS Society (IAS) 2021 took place in July, IDWeek in early October.

As usual, but even more so now with virtual attendance, I’m bound to miss some important studies. Let me know in the comments what those might have been.

IAS 2021 is first up:

Single high-dose liposomal amphotericin-based treatment for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis is just as effective and less toxic than standard of care. This devilishly difficult-to-treat opportunistic infection continues to take a major toll globally, in particular in Sub-Saharan Africa, where this study (called Ambition-cm) took place. The comparator arm (daily amphotericin for a week with 5FC) is both less convenient and has more side effects. Two questions: 1) Can we make liposomal amphotericin and 5FC more widely available? 2) Does this study have implications for us here, where we use two weeks of induction amphotericin and 5FC?

PrEP failures with TDF/FTC may have drug resistance at HIV diagnosis: While the title of the abstract cites “High rates of drug resistance …”, the actual infection incidence was reassuringly rare. This study was done in Africa, giving us a far different view of PrEP than here — 75% women. Out of over 100,000 PrEP users, HIV was diagnosed in 208, and 27 had resistance mutations. Note the higher than expected incidence of K65R, probably because of subtype C virus, along with the transmitted NNRTI mutations.

No selection of INSTI resistance among women in HPTN 084 who acquired HIV while receiving cabotegravir. Good news, and the results contrast with the small rate of resistance seen in HPTN 084 among MSM. One very challenging HIV diagnosis occurred in a woman who had (in retrospect) very early acute HIV (detectable virus but below 40 copies/mL), was randomized to cabotegravir, then had viral suppression and no seroconversion until week 33 of the study. Once this gets into clinical practice, assessments for HIV breakthrough will be challenging! 35/36 of those in the TDF/FTC arm who failed PrEP had suboptimal adherence.

On-demand TDF/FTC PrEP just as effective as daily PrEP among MSM in China. Analogous to the PREVENIR study, here the participants could choose how they wished to take the PrEP — daily or with the 2-1-1 on-demand strategy. In other words, the study was not randomized. An interesting observation — they enrolled MSM who chose not to go on PrEP at all; perhaps not surprisingly, they had the highest HIV incidence.

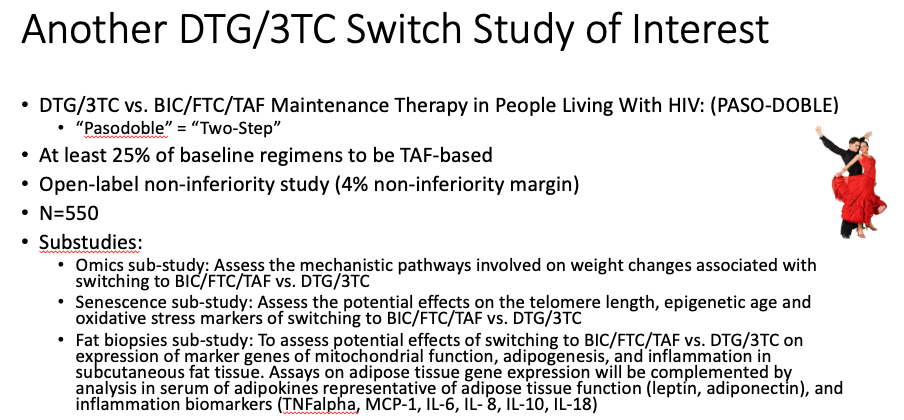

DTG/3TC maintains viral suppression in patients with a variety of baseline regimens. Unlike the TANGO study, where all participants were on TAF-based ART, in this study (called SALSA) they could be on any standard ART regimen, provided no history of treatment failure or resistance. The results demonstrate again that DTG/3TC is clearly a safe strategy virologically for this population. Note that there was more weight gain in the switch arm, likely because around half the baseline regimens included TDF (see first summary from IDWeek, below, for an explanation). An ongoing study — called PASO-DOBLE, get it? — will investigate whether maintenance therapy with DTG/3TC offers objective benefits over BIC/FTC/TAF, such as improvements in metabolic, bone, and various aging outcomes. Here’s a slide summary I made of that study, including the requisite dancers!

Lenacapavir as a subcutaneous injection every 6 months in treatment-naive patients achieves high rate of viral suppression at week 16. There were several different strategies in this phase 2 study which ultimately include two-drug maintenance, but the most novel were those that included lenacapavir given subcutaneously every 6 months (after an oral lead-in) with TAF/FTC. Over 90% had virologic suppression at week 16 (a planned interim analysis); BIC/FTC/TAF had 100%. One case of treatment-emergent resistance to both lenacapavir and FTC occurred in a participant who started treatment with a baseline viral load just over 100,000 cop/mL, implying that the resistance barrier to this novel drug isn’t as high as second-generation INSTIs.

No apparent worsening of outcomes from COVID-19 among people with HIV. This registry-based study included 21,528 hospitalizations, out of which 220 were people with HIV. Given the gazillion studies that have looked at this issue, it’s reassuring to note that not all demonstrate that HIV is a risk factor for more severe COVID-19 disease. My hunch? If you take our healthiest PWH (on ART, viral suppression), and carefully control for demographic factors and comorbidities known to worsen COVID-19, there won’t be much of an effect, if any, of having HIV.

Giving ART to “blipping” HIV controllers improves some immunologic markers. In this observational analysis of 301 controllers followed for a median of nearly 15 years, 90 started ART for various reasons — 83 with viremic “blips” before starting, and 7 with always undetectable viral loads. For those in the former group (the “blipping controllers”), ART led to reduced activated CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes and total CD8 T cells, and increased CD4/CD8 ratio but did not increase the CD4 cell count. No changes were observed in those who were always undetectable. Whether to treat people with this virologic phenotype remains one of the truly unanswered questions in HIV today.

Patients with a history of K65R from prior virologic failure and currently suppressed on ART switched successfully to BIC/FTC/TAF. The study included 71 people, half of whom also had M184V (hence resistance to both tenofovir and FTC). Viral suppression has been maintained in all of them now followed for a median duration of 47 weeks. These results are perhaps not surprising given the results of the NADIA study with TDF/3TC + DTG in people with treatment failure (many of whom had K65R), but they are reassuring to see nonetheless with this slightly different integrase inhibitor. My colleague Serena Koenig is studying this strategy in a randomized clinical trial being done right now in Haiti. Isn’t it remarkable how NRTIs retain activity even after genotypic (and high-level phenotypic) resistance?

Shifting now to IDWeek, with a few HIV and in particular COVID-19 studies of note:

A meta-analysis of seven clinical trials in 19,359 HIV-negative people shows that TDF is associated with weight loss. The strength of this comprehensive study is that the control arms received placebo, and that any “return to health” (which leads to weight gain) from treatment of HIV is excluded. The mechanism by which TDF induces weight loss is not clear, but we should definitely counsel our patients that discontinuing this drug may lead to weight gain. Some big questions remain — why does TDF do this more in some people than others? What is the mechanism? Is it harmful or salutatory? And — not relevant here, but clearly the case — why is the effect strongest when TDF is given with EFV?

Antibody responses to COVID-19 vaccines may be impaired in some people with HIV. Leading predictors of a good response were CD4 cell count (higher better), suppressed HIV RNA (suppressed better than viremic), and which vaccine was given — mRNA-1273 (Moderna) did better than BNT162b2 (Pfizer).

Another dual monoclonal antibody treatment reduces the risk of hospitalization and/or death in outpatients with COVID-19. The antibodies are BRII-196 and BRII-198, and the effect was in line with other treatments — a 78% reduction in risk. Provided there is no viral escape, I suspect the distinguishing characteristics of these various treatments will be their pharmacologic properties — half-life, formulations, mode of administration, cost. If that’s not enough for you …

Regdanvimab reduced the risk of hospitalization in high-risk outpatients with COVID-19. Hospitalizations occurred in 4.0% of the treatment group, and 8.7% receiving placebo, a 70% reduction in risk. (Amazing how consistent these results are.) Apparently regdanvimab binds to a different location in the spike protein than the other monoclonals.

AZD7442 (Tixagevimab/Cilgavimab) given as pre-exposure prophylaxis to high-risk outpatients significantly reduced the risk of acquiring symptomatic COVID-19. After 83 weeks of follow-up, only 8/3460 (0.2%) of the AZD7442 group vs. 7/1737 (1.0%) of those receiving placebo developed COVID-19, a 77% reduction in risk. Importantly, the study population was not vaccinated, and only 4% were high-risk based on being immunocompromised. Nonetheless, the results strongly suggest that AZD7442 — given as two 1.5 ml IM injections — will be a viable prevention strategy for the not insignificant population of immunocompromised people who have suboptimal responses to vaccines. The company has requested Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for this indication — there will be many patients eager for this treatment!

Another study demonstrates that casirivimab and imdevimab improves outcomes for hospitalized patients. We’ve known about the survival benefit of this treatment for seronegative patients from the RECOVERY trial for several months. Here a similar finding of benefit — a reduction in mortality — was found for the seronegative patients, with no signal of harm in those who were seropositive. This treatment (better known as REGEN-COV) is now limited in the United States to outpatients at high risk for COVID-19 disease progression, or for post-exposure prophylaxis. The results of these two studies suggest that modification of the current EUA to allow inpatient use, at least for seronegative patients, cannot come soon enough!

Remdesivir for 3 days given to outpatients with COVID-19 significantly reduced the risk of hospitalization. Only 2/279 of those receiving remdesivir required hospitalization, vs. 15/283 receiving placebo, an 87% reduction; there were no deaths in either arm. No effect was observed on nasopharyngeal viral load, raising the question — are we measuring the right surrogate? While giving remdesivir for 3 days to an outpatient to someone with active COVID-19 would be no picnic, these results are in many ways the strongest efficacy data we have for the drug — and underscore that if giving remdesivir to hospitalized patients, it should be started early (inclusion criteria required symptoms for a week or less). The same likely applies to any antiviral agent.

Am sure there are plenty of studies that I missed, but these in particular caught my eye. And for now at least, in-person meetings have started to return, with many (all) also having a remote option — so-called hybrid meetings. Denver will host a hybrid CROI in February 2022, and we just had a hybrid EACS in London, where my friend Joel Gallant attended.

Here’s his front-line experience:

I’m attending the hybrid EACS in London in person, my first face-to-face conference since the pandemic began. It’s strange to be sitting in a large, largely empty conference room watching a bunch of speakers give pre-recorded virtual talks on a big screen. In many cases there’s no one on stage at all. It’s as though the Zoom meeting has been turned into a spectator sport. But at least it’s easier to get a table for lunch than at most conferences.

Don’t you love pandemic silver linings?

Hey, in case you have some leftover pumpkins after Halloween, here’s something you can do with them.

October 12th, 2021

A Few Thoughts on “Attending” Virtual Meetings

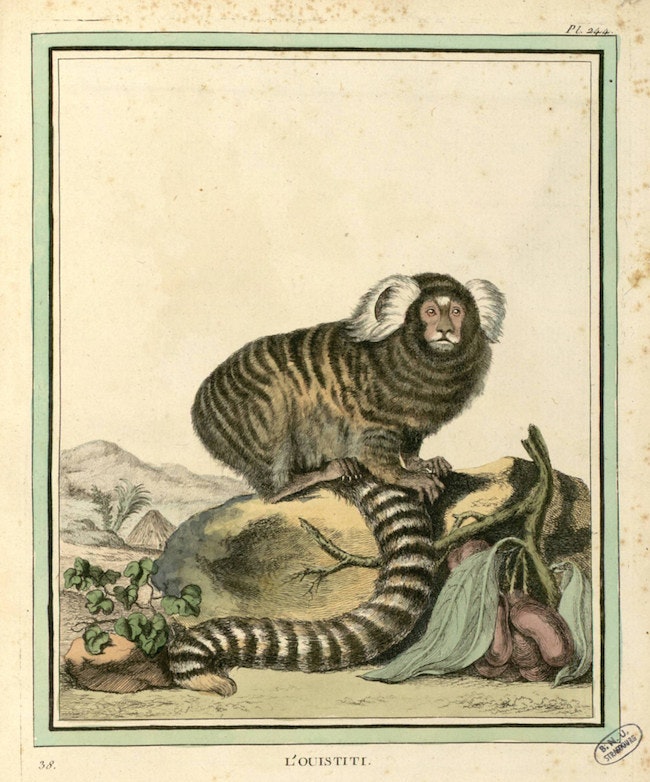

Ouistiti (marmoset), from Buffon and de Sève’s Quadrupeds (1754). Apparently the French say “ouistiti” instead of “cheese” before a photo — perhaps somebody who’s actually from France can confirm or refute.

Once upon a time, long, long ago, before SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19, many of us in academic medicine attended in-person scientific meetings that took place annually around the world.

I was one such person — usually 2-3 times a year. My primary charge at each of these meetings was to assemble the best, or most interesting, or most controversial clinical science and summarize it. Usually, I did this the weekend after the meeting, writing it shortly after walking my dog Louie on Sunday.

He was a very helpful editor.

I called them Really Rapid Reviews©, posted them here, and sent a stern letter to the US copyright and patent offices saying that under no circumstance could anyone copy them and sell them for profit. My crack legal team would be all over violators with the full force of the law.

While that last part (the copyright-patent-legal part) might not be true, the rest of the above narrative is 100% verifiable in these archives.

But then COVID-19 happened. Virtual meetings replaced the in-person scientific ones. I was so overwhelmed after Virtual CROI 2020 — through no fault of the conference, hey it was March 2020 — that I barely remember any of the content, though I did manage to cover one very important study.

Fast-forward roughly 18 months to now. Yes, many of us still “attend” (note the quotes) these virtual meetings — which means for most of us that you go to work as usual and try to snatch some free time to watch pre-recorded presentations on things that sound interesting.

Or you don’t. “Many sessions are like articles I’ve put aside and never get around to reading,” says Dr. Neil Clancy, offering up a perfect analogy. The problem? “Virtual really doesn’t help me disengage from clinic or other duties,” says Dr. Woc-Colburn. Exactly.

If this isn’t enough of a struggle — and believe me, it is — each meeting’s website has a different format, fraught with perilous glitches, sign-in pages that forget who you are, distracting “rooms” and “avatars”, and search function dead-ends. Don’t they know by now that the search function is the #1 key feature in all of these virtual meetings?

Plus, what about the non-meeting activity that happens at meetings? Says Dr. Neil Stone, “Nothing quite replaces the interpersonal connections made at conferences. The conversations you have over a drink at the end of the day are often far more important than sitting listening to the talks, the content of which you often know of in advance.” Indeed this is true!

Grrrr. You can tell I’m not a huge fan of the virtual format — it’s wearing me out.

But for the sake of argument, let me take the side of the virtual meeting proponents.

- There’s that COVID-19 thing — yep, still here, and putting crowds together doesn’t sound like the safest activity. Remember the Biogen Leadership Conference?

- For people with little flexibility in their work or family responsibilities, in-person meetings are out of the question — hence virtual meetings offer the opportunity for a much broader group to attend. No need for the quotation marks around the word attend this time.

- Regardless of your work or home duties, in-person meetings cost a lot, take a ton of time, and are absolute beasts from a carbon footprint standpoint. Let’s not feed that beast!

These are all legitimate points.

Which is why my hope for a post-pandemic world — whatever that means — is that we’ll have the option of both. That’s what’s planned for CROI 2022, and expecting the same from many others.

Looks like you agree:

Let's assume some scientific meetings in 2022 are hybrid — in-person or virtual. Which will you be choosing for those you used to attend? Why?

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 11, 2021

Oh, and since someone asked, the Really Rapid Review© of two recent meetings are all but written. No, they’re not so rapid anymore, but who’s keeping track these days.

October 1st, 2021

A Thank You to One of Our Best Patient-Teachers

Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital lost one of their best teachers this week.

Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital lost one of their best teachers this week.

No, it wasn’t a distinguished professor or astute clinician.

It was one of my long-term patients, who had given himself selflessly to teach dozens of medical students, residents, and (especially) ID fellows over the nearly 30 years I’d known him. Let’s call him Tony. Boy, are we going to miss him.

He worked in a fancy haircutting salon in Boston, where he was highly popular. We first met in the hospital room of his longtime boyfriend in the early 1990s, a grim time for HIV disease. His partner was dying of aggressive lymphoma; I was consulted on the case because of persistent fevers, but there was little we could do.

When our brilliant and perceptive social worker realized that Tony — clearly a kind and friendly man — would soon be alone, she reached out to him.

“How are you doing?” she asked.

“Not so well,” Tony said. “My test is positive too. And I hate my doctor.”

Yes, that could have been a red flag for a difficult patient. But it turns out Tony’s doctor really wasn’t a good match — he was highly judgmental about the fact that Tony had HIV. “He spends more time telling me not to spread it to others than he does trying to help me. I can’t stand the guy.”

So I became his doctor. Over the next few years, Tony’s CD4 cell count fell, he suffered several HIV-related complications, and required admission to the hospital a few times — but through it all he remained cheerful and unfailingly nice. When able, he continued to work full time at the salon, sometimes walking over to the Ritz-Carlton to blow dry a fancy person’s hair before an important event.

“It’s important to them!” he’d say, proud of being in demand. “Plus the money is great.”

Tony had a humble background — he was born in another country, raised in a “rat-infested” (his words) apartment by immigrant parents who didn’t speak English, and he never attended college.

No matter. He got along with everyone — not just the fancy ladies (it was mostly ladies) at the Ritz, but also our aforementioned social worker, our front-desk staff, our nurses, and most notably, our ID fellows.

Over the next 29 years, he must have seen at least a dozen different fellows as they went through their fellowships. He treated each one of them like his primary ID/HIV doctor, never once acting as if they (as trainees) were just “pretend doctors” waiting for the “real” doctor (me) to show up. You can’t imagine how important and empowering that attitude is for doctors in training.

Plus, he agreed to speak at Harvard Medical School classes several times a year, sharing his stories about what it means to live with HIV in the United States. In these sessions, he generously offered his unedited views on American medicine, never sparing certain doctors he’d met with lousy bedside manner.

“He treated me like I was his next down payment on his Cape house,” he said about one particularly aggressive surgeon. “Cha-ching!”

Nope, he wasn’t shy. But what great teachable moments for these young doctors-in-training.

Why do some patients embrace this role in our teaching hospitals? What is it about their personality, and makeup, that gives them the generosity of spirit to help train clinicians? And conversely, why do some people go to a teaching hospital and resent, ignore, or avoid the students, residents, and fellows, treating them as an inconvenience? Don’t they know what the word “teaching” in “teaching hospital” means?

Although I don’t know the answer to these questions, I can assure you that we physicians are exceedingly grateful to the former group for their taking on this very important role — something I told Tony repeatedly over the many years I knew him.

One of the privileges of being an HIV specialist all this time, of course, is witnessing the transformation of this previously fatal disease into one that’s treatable. Tony faithfully took combination antiretroviral therapy as soon as it became available in 1996, and it saved him from dying of HIV. His virus has been under control since then.

Not dying of HIV means that regular diseases of aging start to take their toll, and these did not spare Tony, in particular because he was a lifelong smoker — severe osteoporosis, arthritis, COPD — and innumerable aches and pains plagued him. When he started to lose weight earlier this year (he was already rail thin) a workup quickly established he had pancreatic cancer. “It’s the cancer that gives cancer a bad name,” one Dana-Farber doctor memorably told me.

It was only a couple of months from his diagnosis to his death this past week. He was surrounded by his family, friends, and most importantly, his current partner.

When I mentioned just how grateful I was for all the generous teaching Tony had done over the years, his partner shared that he drank his morning coffee each day always from the same mug.

“It’s a Harvard Medical School mug,” he said. “Has to be that mug.”

Makes sense.

And not bad for a guy who never went to college.