An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

August 8th, 2022

Long-Acting Injectable HIV Therapy for People Who Won’t Take ART?

Atlas. Lee Lawrie and Rene Paul Chambellan, 1937.

HIV treatment is so spectacularly effective that you might be surprised to hear that some people with HIV still have uncontrolled viral replication. We HIV clinicians watch with frustration and sadness as they experience progressive immunodeficiency, complications from advanced HIV disease, hospitalizations, and HIV-related deaths. Plus, while viremic, they continue to risk transmitting the virus to others.

What’s the barrier to successful treatment? In 2022, it’s almost never drug resistance. It’s that they can’t, or won’t, take oral antiretroviral therapy. Excluding those completely out of care (that’s a different problem), I’d estimate from various studies that they typically represent around 5% of a clinic’s population.

The percentage with uncontrolled HIV is higher in places like Ward 86, the safety net HIV clinic at UCSF — around 15% by their estimates. True to its mission, the clinic serves many people struggling with poverty, substance use disorder (especially cocaine and crystal methamphetamine), unstable housing, psychiatric illness, and low medical literacy. That’s why the case series they just published using long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine (CAB-RPV) is so remarkable.

That’s right — cabotegravir and rilpivirine for this highly challenging patient population, a group most certainly underrepresented in the pivotal clinical trials ATLAS and FLAIR.

Out of 132 people in Ward 86 referred for CAB-RPV treatment, 51 started injections. Of these, 39 patients had at least two treatments and were included in this report. The good news: All those with virologic suppression at baseline maintained HIV control during the follow-up, a tribute to the enhanced care provided by the team of clinicians involved in the program.

But by far, the most notable aspect of this report is what happened to the 15 people who were not on suppressive ART — in other words, the group highlighted in the first paragraph of this post, those not taking their meds.

This viremic group had a median CD4 cell count of 99 and a viral load of around 50,000 (with one over a million); a patient with resistance to raltegravir and elvitegravir (harboring the N155H mutation) was also treated. Despite these unfavorable baseline characteristics, 12 of 15 achieved virologic suppression (including the person with N155H), and the other 3 have HIV RNA that has declined by more than 2 log.

Although long-acting CAB/RPV is FDA-approved only for PWH w/ viral suppression, this remarkable case series (new in @CIDJournal) shows it can work also in those with viremia — where it could be a life-saving intervention. Clinical trials urgently needed. https://t.co/GvBQ0AtEvC pic.twitter.com/Z38ybgyLoe

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) August 4, 2022

Wow.

These exciting results notwithstanding, it deserves emphasis that using CAB-RPV for viremic patients takes us way outside the indications outlined in the FDA approval. This specifically stated that the treatment is for those “who are virologically suppressed (HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL) on a stable antiretroviral regimen with no history of treatment failure and with no known or suspected resistance to either cabotegravir or rilpivirine.”

There are plenty of additional caveats about using CAB-RPV in people not taking oral ART. The study includes just a small number of viremic patients, and the follow-up is relatively short (less than a year). We can’t say whether virologic suppression will be maintained, or what proportion will drop out of care and miss their injections, or how many will develop the much-dreaded two-class drug resistance to both integrase inhibitors and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors — resistance that will make subsequent treatments much more challenging. Plus, payers in some regions may not be as generous in covering treatment for a non-FDA approved indication.

It’s also worth remembering that Ward 86 is a special place, hardly representative of most HIV, ID, or primary care clinics. They have tons of dedicated on-site resources to enhance the care of their difficult-to-reach patient population. This includes doctors, nurses, pharmacists, social workers — a veritable army of people available to support and chase down people who might go astray while on HIV therapy.

Example: Two of the patients in this report with unstable housing received injections in the community with “street-based nursing services.” (When I wrote “chase down,” this is what I meant.) How many of us HIV providers have access to this kind of wraparound care? In other words, if you’re in a standard ID or HIV clinical practice, don’t try this at home quite yet.

These caveats notwithstanding, I maintain that this novel use of CAB-RPV is highly important, and that it’s critical it be explored further. Up to this point, our options for people who won’t take oral ART have been highly limited. In desperate cases, we’ve even resorted to feeding tubes to administer ART, these placed during prolonged hospitalizations for AIDS-related complications. If CAB-RPV can provide even half the people who won’t take oral ART an effective option, use in this population will be save more lives than CAB-RPV will through its FDA approved indication. After all, those people are by definition doing well on ART!

The alternative to trying this might be an HIV-related death. And no one in 2022 should die of AIDS without our doing everything we possibly can to get them on antiretroviral therapy.

Even if that includes an unapproved use of cabotegravir and rilpivirine.

July 22nd, 2022

The Paperwork Demands for Academic Medical Teaching Are OUT OF CONTROL

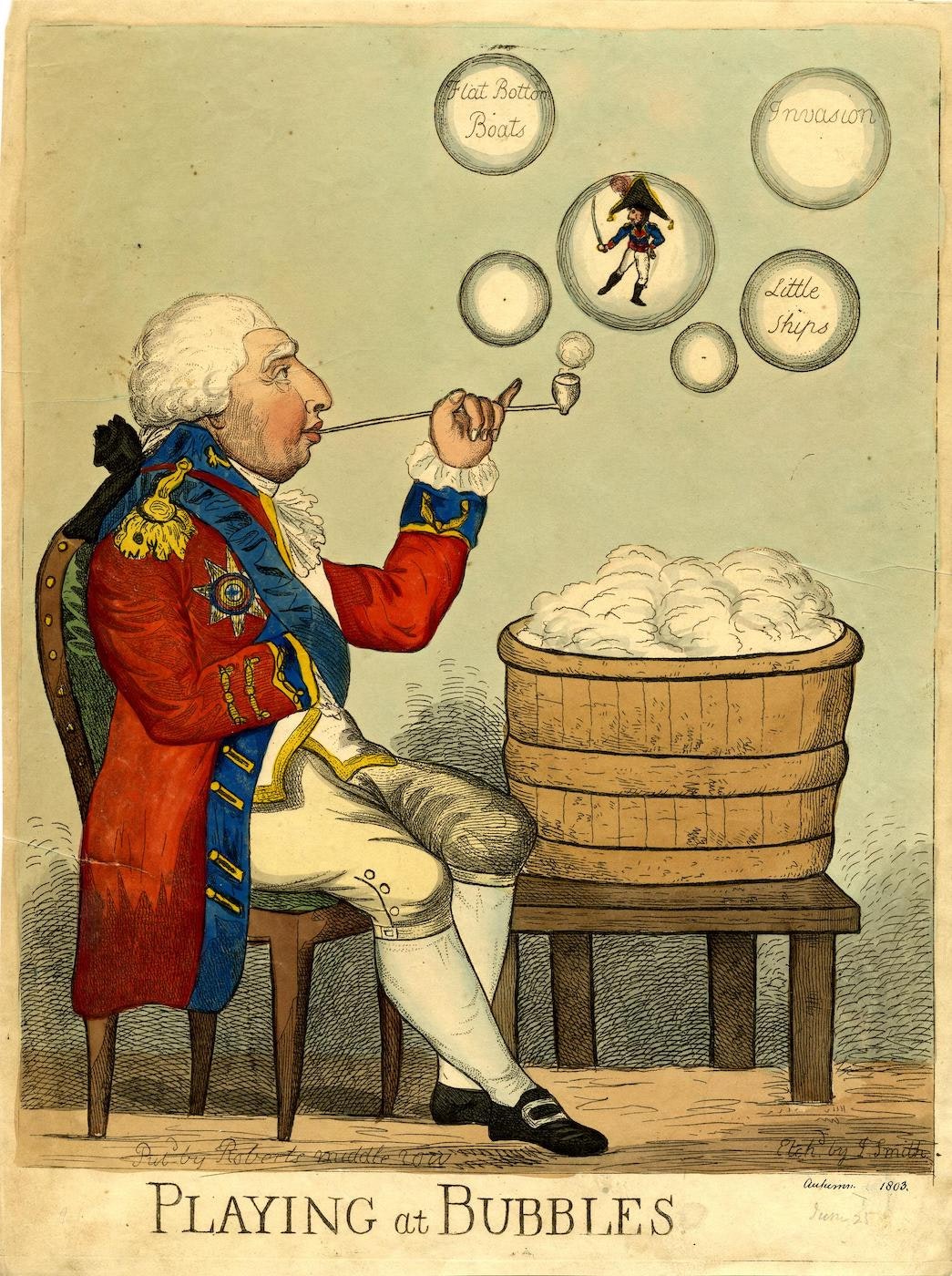

Playing at Bubbles, Piercy Roberts, 1803.

Why all caps in the above title? It’s to call attention to a problem that’s getting worse each year in academic medicine, especially when it involves teaching or talks.

The requirement to submit a veritable truckload of forms, documents, attestations, and summaries, all due months before the actual event.

Let’s explore in more detail what this might involve — and I assure you, what is outlined below is no exaggeration.

After accepting an invitation to teach, give medical grand rounds, or visit an academic medical center, you might receive an email from a “person” with an anonymized email such as “Internal Medicine Administrative Services” or “Medical School Education Coordinator.”

You know those emails that you dread to open because they have so many attachments that you barely know where to start?

Some of these emails have four or more attachments, plus additional secure links (which may ask you to create usernames and passwords), and numerous deadlines for all the required documents. Can an email weigh a lot? If so, these email behemoths are comparable to the Wile E. Coyote’s anvil on the Road Runner cartoons, the 16-ton weight from Monty Python, or Laurel and Hardy’s pianos.

If such emails fill you with dread, it’s because of the Fifth Law of Thermodynamics — otherwise known as Sax’s Law of Email Avoidance: A person’s reluctance to open an email and deal with it promptly is proportional to the square of the number of attachments. Example: An email with four attachments is 16-times more likely either to sit unopened and/or not get completed efficiently than one with only a single attachment.

Now let’s review the required items:

- Last name, first name, degree(s).

- Hospital and academic titles.

- Head shot. When submitting this photograph, those of us of a certain age might be tempted to choose something from a couple of decades ago. Fountain of Youth.

- Presentation title and date. It’s slightly annoying that all of this information from these first four items is either already known to the inviters (certainly the date) or available via a simple web search, but I’ll grant them these requests as we’re just getting started.

- Updated Curriculum vitae. Got to check those qualifications!

- Abbreviated biography. These are those braggy paragraphs that a person writes to help with introductions. Maybe I’ll include the fact that I won an essay writing contest about yogurt several decades ago for Boston’s Real Paper — or was it the Boston Phoenix? — allowing me to be on a panel of taste testers to identify Boston’s best brand. Or that I listed in my college yearbook that I was a member of a club called the “Leverett Luggage Society,” a club that did not exist.

- PHI query and permission form. PHI stands for “Protected Health Information,” meaning identifying information about patients. If any of this information is in your talk, it will require an additional signed form from the patient. Note to teachers everywhere — unless absolutely necessary, try not to include PHI in your talks. Seriously. Just not worth it. You can use a case-based approach to teaching, but modify the case sufficiently so that it does not include identifying information.

- Three (sometimes four) learning objectives. Before submitting these, you could be referred to “OCME requirements” for guidelines on how to write good Learning Objectives — these might come on a separate attachment — or you could be referred to the OCME web site. “OCME,” in case you’re wondering, stands for Office of Continuing Medical Education, not Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, or Orange County Model Engineers. The last of these, I’ve learned, was founded in 1977 and offers free rides on trains that operate like real locomotives, but are 1/8 the size of the real thing. See what can be learned from a quick web search? And before going on, I could write an entire post on these “learning objective” requirements which, as I’ve noted before, rarely lead to more learning, but sure are annoying to write.

- OCME disclosure of relevant financial relationships. Every talk requires this information — it’s a list of potential conflicts of interest — but despite the universality of this requirement, there are as many different forms for this information as there are stars in the sky — like snowflakes (to shift metaphors), no two are alike. How about all these Orange County Model Engineers hop off their mini-trains and come up with a standardized form? For a while I just submitted a Word document that listed potential conflicts of interest, and wrote in caps on all the proprietary forms — “SEE ATTACHED DOCUMENT.” That worked for a while, but nobody accepts that one anymore.

- OCME mitigation of relevant financial relationships. And if you do have some relationships, you will need to fill out an additional form, one which includes multiple questions (often as many as a dozen) to satisfy the organizers that these potential conflicts can be resolved. Here’s an example, taken from a recent form: “If I am discussing specific healthcare products or services, I will use generic names to the extent possible. If I need to use trade names, I will use trade names from several companies when available, and not just trade names from any single company. My learning objectives may not include trade names. (Check Agree or Disagree.)” Easy for me — I’m one of those nutty ID docs who says “trim-sulfa” rather than Bactrim, “cephalexin” rather than Keflex, and “pip-tazo” instead of “Zosyn,” both because I hate using trade names (especially when the drug is long off-patent), and because the last one always reminds me of Led Zeppelin’s 4th album, which is distracting.

- A list of references, and a PDF of a relevant published paper. If you’re really unlucky, there will be a requirement for an annotated bibliography, explaining why this paper was selected for this talk — oh the pain. For medical schools out there reading this post, please don’t get any ideas. “PDF,” by the way, stands for Portable Document Format, not Probability Density Function, or Pigs Do Fly. Just so you know.

- Speaker agreement form. This includes permission for use of your image in pre-talk announcements, as well as miscellaneous photographs, audio, and video taping. Of course it needs a signature — one of many documents in this bundle that needs a signature, even though all this stuff flies around electronically, and “e-signing” different forms presents its own form of digital torture.

- Four “board-style” multiple choice questions related to the talk material. If the course organizers are in a particularly demanding mood, they might ask you also to ensure these questions specifically linked to the dreaded Learning Objectives, see item #8. Crafting high-quality “board style” questions — with one right answer, and plausible alternatives — is particularly challenging, time consuming, and painful. Reminder: “Good enough but completed” wins here every time over “Excellent but time consuming”.

I realize that these requests are not the fault of the conference organizers or education coordinators — they are responding to requirements issued by others, usually medical schools or accreditors. Anyone who runs a post-graduate course feels this pressure, including me.

But wow, is it ever a disincentive to teach.

OK, I’ve complained enough. Now it’s time for a solution to this quagmire.

How about this approach, which was taken by a very kind person who invited me to give a lecture earlier this year?

Hi Dr. Sax, hope you’re well. We’re planning our annual conference this year, and would be delighted if you would be one of our speakers on [insert ID topic here]. Don’t worry about paperwork — we’ll take care of it — just provide us the talk title and a list of your financial disclosures, if any. We’ll also send you some proposed learning objectives for your review and approval a few weeks before the conference.

Thank you for considering!

Ellen

And thank you, Ellen, for making it so easy! And for the record, your email was light as a feather.

July 1st, 2022

Fellowship Transition and Developing a Sense of Belonging

Always a good time for a cute puppy picture.

It’s July 1, which means that today, or sometime very soon, many internal medicine residents will transition to becoming subspecialty fellows.

There are many appropriate words to describe this change, including exciting, nerve-wracking, and challenging, but one that doesn’t get quite enough attention is how strangely lonely it feels. The reason this sensation occurs is because medical residencies — through their size, structure, and voluminous shared experiences — engender a powerful sense of belonging. The bonds between you and your co-residents are strong indeed, especially after three years together.

Fellowships can’t instantly create this comforting feeling. Your fellowship group is smaller. You typically work alone, with an attending, and not as part of a team. Plus, there’s the disquieting experience of having mastered something (the bread and butter of inpatient clinical medicine), only now to be plunged into the uncertainties of a specialty that you haven’t yet learned.

How many incoming ID fellows are more comfortable managing chest pain than postpartum fever? I’d estimate it’s 100%.

If one adds to these factors the geographic relocation that may occur, it’s not surprising that subspecialty fellows take some time to feel really part of their new tribe.

Proof that the bonding of medical residency takes time to wear off is that most fellows spend the first part of their fellowship using the word “we” to describe their residency group, not their fellowship.

Here’s a smattering of select phrases that might be heard during the first few months of ID fellowship:

We used ceftriaxone and doxycycline, not azithromycin.

We would do the thoracentesis ourselves.

We don’t use procalcitonin, it’s not reliable.

And of course, the classic (and inevitable):

We would never consult ID on a case like this.

I completely get it and went through the same thing as a first-year fellow. I distinctly remember telling an inpatient medical team that their choice of antibiotics for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis was wrong — because “we” did it differently during my residency. A residency done at a different hospital, of course.

(For the record, it wasn’t wrong. It was just different.)

So to those of you making this transition, we (meaning the ID community) totally understand how you’re feeling. We want you to feel welcome and part of our ID world. It might take a little time, but you’ll get there.

Pretty soon, you’ll start saying “we”, and when you do, you’ll mean you and other ID docs like you. I promise.

Welcome to the club.

June 21st, 2022

Mayo Clinic Study on Paxlovid Outcomes is Reassuring — but Likely Underestimates Rebound Rate

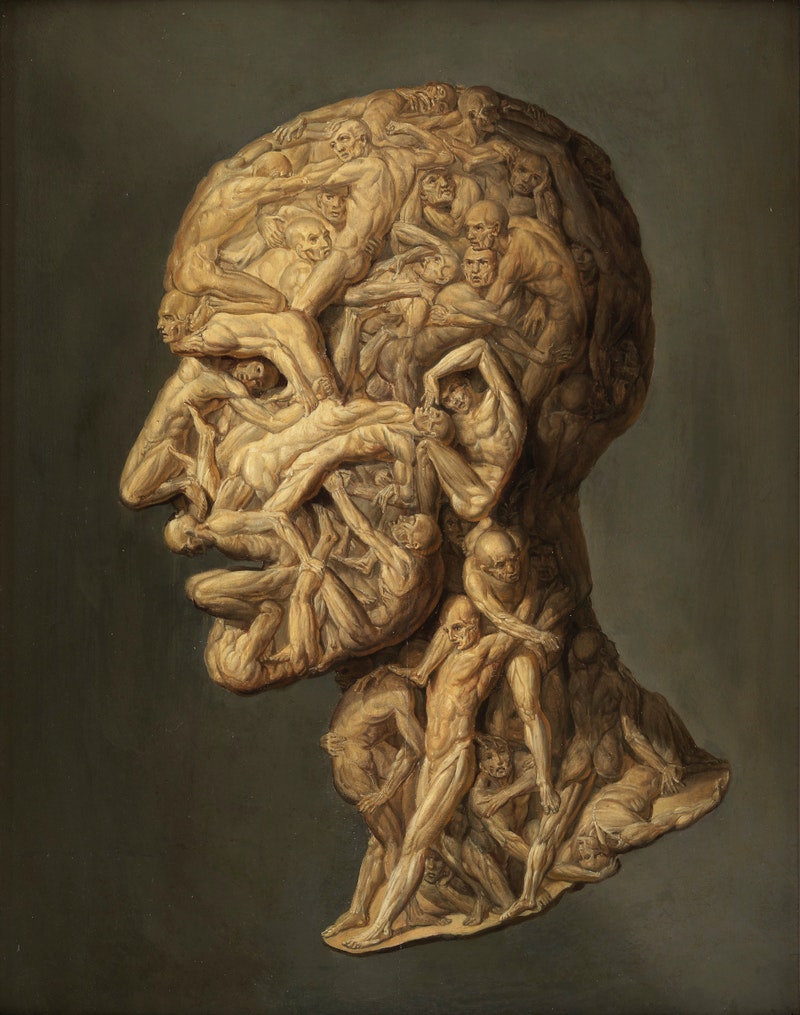

Filippo Balbi, Testa Anatomica, 1854.

Over at Clinical Infectious Diseases, researchers from the Mayo Clinic published a retrospective analysis of nirmatrelvir/r (Paxlovid) treatment, with a careful review of each patient’s chart.

The goal was to determine the clinical outcomes after the 5-day treatment course, with a focus on the frequency of rebounds — a topic of great clinical interest but with little real-world data with a decent-sized denominator.

The study included 483 patients with at least some risk factors for severe COVID-19 based on the institution’s Monoclonal Antibody Screening Score. Adjudication of eligibility was done centrally through the hospital’s COVID-19 outpatient treatment program. The mean age was 63, and 93% were vaccinated. Patients were given the option of telemedicine follow-up and encouraged to self-report symptoms or other problems; this information and their full electronic medical records were reviewed after the treatment.

Out of this group, 4 (0.8%) clearly experienced clinical rebound — these cases are described. None of the 4 received re-treatment or were hospitalized. Two other patients (neither of them rebounders) did require hospitalization, but the authors note these were unrelated to COVID-19. There were no deaths.

We can be reassured by the information on the low rate of severe outcomes, an outcome mirrored in low hospitalization rates nationally despite lots of ongoing cases. Rates of hospitalization for each COVID-19 case are now extremely low, especially among those vaccinated, and observational studies (peer-reviewed and published and unpublished) suggest that Paxlovid may reduce this risk even further. A large retrospective study from Kaiser Permanente Southern California involving 5,287 patients found similarly low hospitalization rates.

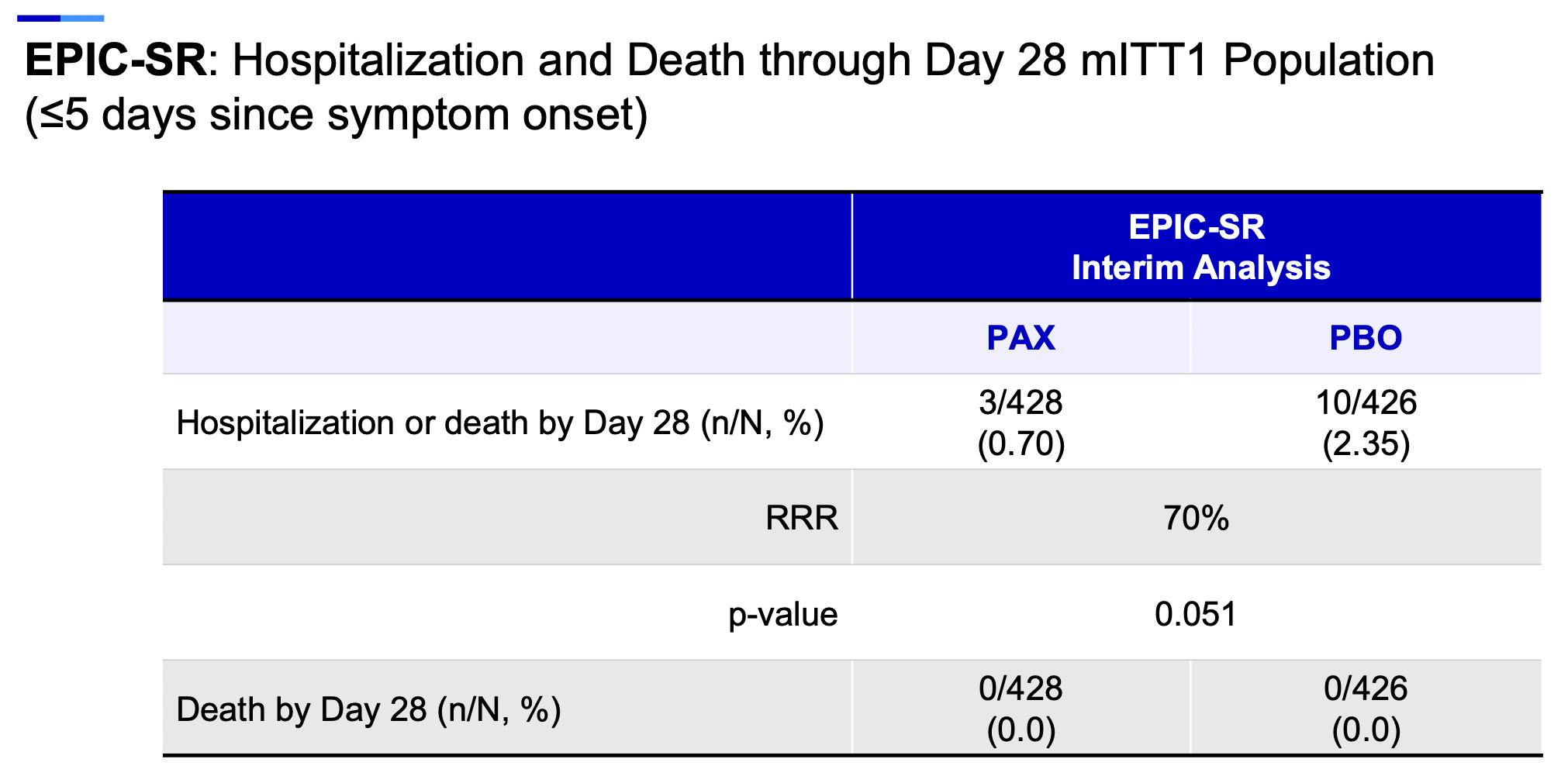

(Note that these observational studies include patient populations treated with Paxlovid with established risk factors for COVID-19 adverse outcomes — that’s how it’s mostly prescribed under the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA). By contrast, those enrolled in the EPIC-SR study, which was recently stopped due to futility, were “standard risk”. Critically important will be information on baseline characteristics in EPIC-SR.)

For the Mayo study, the authors are to be credited for collecting and reporting the data so quickly, especially at a time when clinicians and patients increasingly observe the rebound phenomenon and wonder what to do about it. The centralized program used for distributing COVID-19 treatments is an additional strength of this report, as it allowed participants the opportunity to self-report progression of symptoms, and upfront ensured that all who were treated met the criteria for high risk based on the EUA.

The big limitation of this Mayo study, however, is that it’s retrospective. As a result, I strongly suspect the 0.8% rate of rebound substantially underestimates the true incidence. Pfizer reported rebounds in 2% of study participants in the prospective EPIC-HR trial, a rate more than twice as high. Based on anecdotal experience — there’s lots of Paxlovid treatment out there! — I would not be surprised if it’s at least 10 times this high, or in the 5-10% range.

What still remains unknown, frustratingly, is whether treatment with subsequent rebound reduces — or paradoxically increases — the total amount of time that people are contagious, or, if the total time is the same, does it just delay the time that a person can confidently say that they’re in the clear?

Why is this important? I’ve had people tell me that they don’t want to take the drug because they’ve heard it might lengthen the time they’re contagious. And I’ve had other patients who experienced rebound express regret on having taken the drug — even though we have no idea whether they would have tested positive for a prolonged period even without the treatment.

Let’s hope further data from prospective studies give us some answers — in particular, the placebo-controlled trials, either Pfizer’s two studies or the large PANORAMIC trial done in the United Kingdom.

In the meantime, I’m still advising people at higher risk for COVID-19 adverse outcomes — even if vaccinated — to be treated with Paxlovid, uncertainties about the above issues notwithstanding.

June 6th, 2022

Still More Fun with Old Medical Images

Back in the Before Times, this site would occasionally dabble in lighter fare:

- Cartoon caption contests

- Commentaries on doctor attire

- Thoughts on the first-name “Morgan”

- Penguins chasing a butterfly (Well, actually, this is a new one!)

https://twitter.com/buitengebieden/status/1533022340887486466?s=20&t=ShPbhfDhg-BwCP2bWisXfA

And, the subject of today’s post — Fun with Old Medical Images.

Here’s how it works: We display an old medical image — something with long-expired copyright protection to reassure my editors and keep me out of trouble. Then, through the magic of the internet, I give it a fresh caption and a brief commentary. It may or may not have an ID theme.

Surprised that something with the NEJM Group imprint would stray into such territory, you will then smile at the incongruity and maybe even laugh a little. All for the usual bargain price of this fine content.

(We accept all major credit cards, PayPal, and cryptocurrency. And, I’ve been told, your purchase is FSA-eligible for reimbursement.)

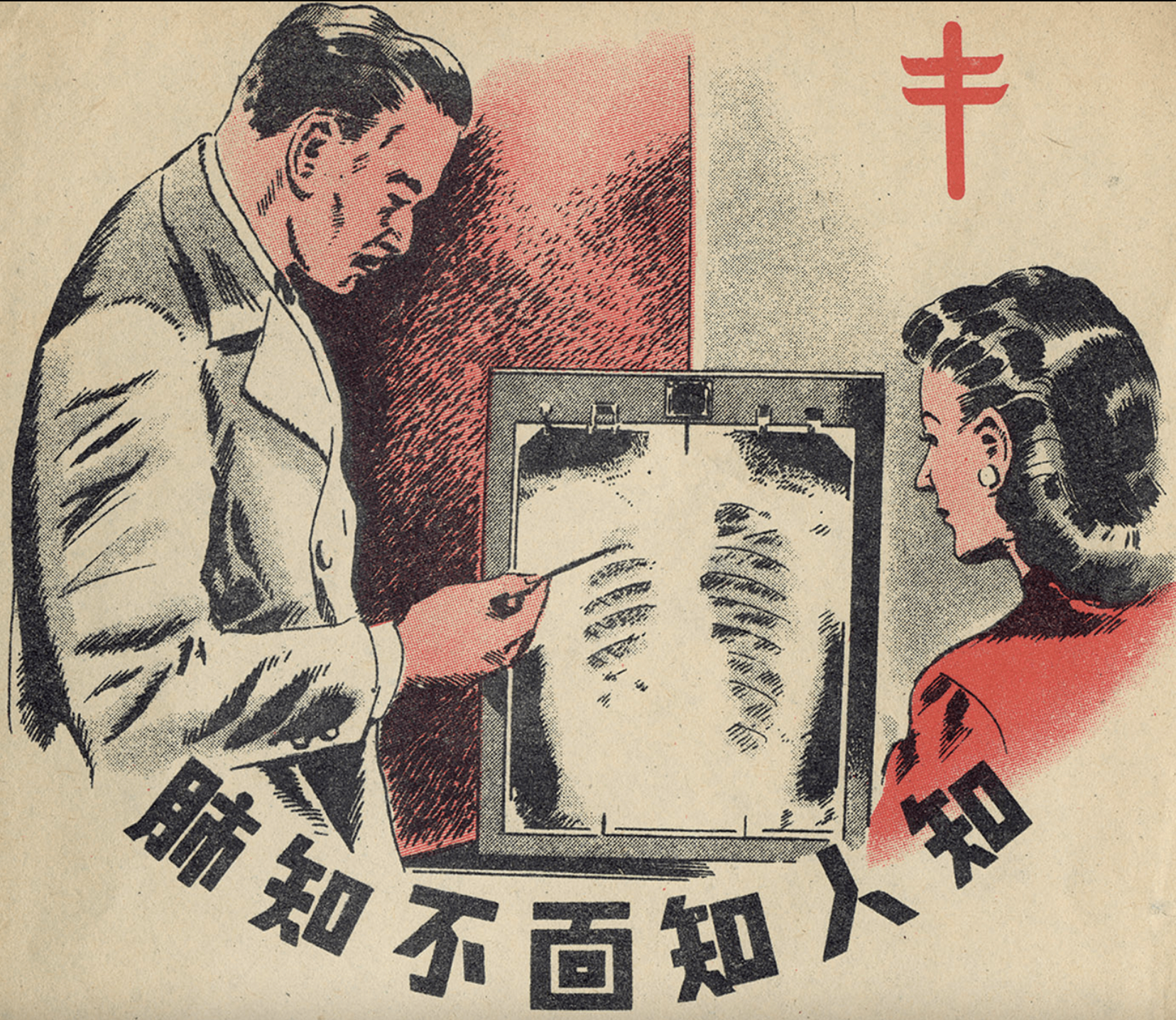

Off we go with #1 — always good to start with an ID one:

“And this here, Miss, is why I’m going to get my N95 mask.”

Could it be TB? It can always be TB. Better take precautions!

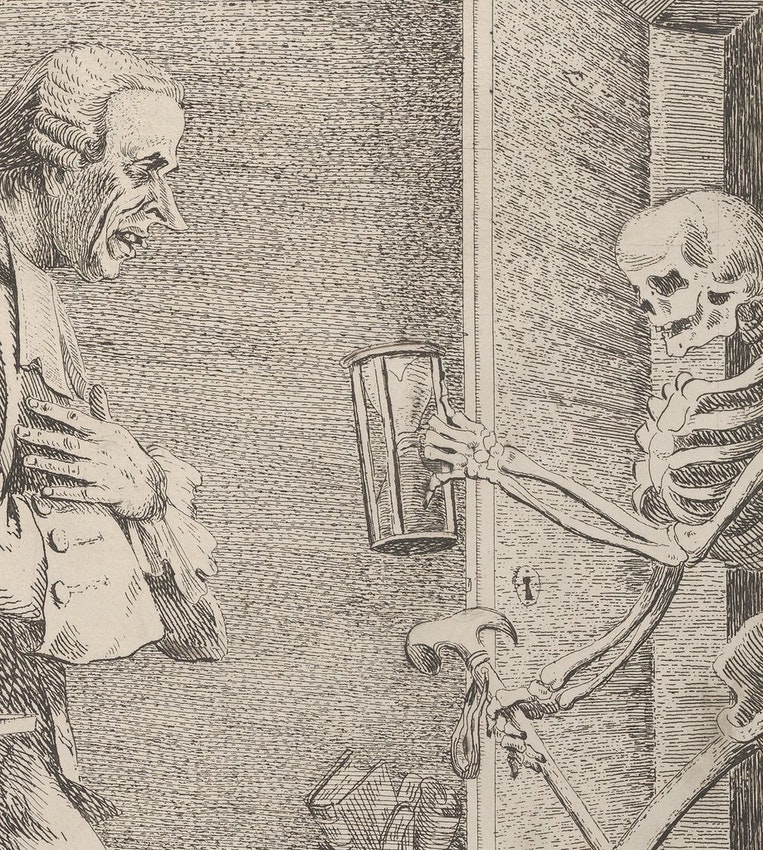

Now, for #2, a grim visitor — or is it?

“Didn’t you say you wanted a cup of sugar?”

Don’t judge a book by its cover — or more accurately, don’t prematurely judge a scary skeleton handling an hourglass as a portent of death. He’d heard you needed a kitchen staple and is just being neighborly!

There’s plenty of time to finish baking that cake before the scythe deals its final blow.

Let’s stay (roughly) with this time period — early 19th century, according to my crack research team — with #3:

“Thorsten, time to check again on that prior authorization for semaglutide.”

Ah, the travesties of insurance coverage and prior authorizations — a problem even in 19th-century England, I guess!

Please note the tried-and-true humor technique I used there, mixing the old image with a modern concern. Yes, it’s easy, but remember — these are Old Medical Images. And I’m not that old. Never saw this one in medical school, for example.

Let’s get fit with #4:

Gertrude didn’t consider it a full workout until she’d completed at least 30 minutes on the automated Exer-Master.

Well of course she didn’t consider it a full workout — that side-saddle mount looks mighty comfy, and the powerful Exer-Master® engine is doing most of the work! Get this person a Peloton! Then she’ll know the meaning of “exhaustion for those with disposable income.”

For #5, we’ll visit a commonly done test on inpatient medical services everywhere:

The medical team was pleased that the patient easily passed his swallowing study.

No mechanical soft solid diet for him! And don’t make the “have a frog in your throat?” joke — he’s sensitive about that.

Let’s finish with #6, a more modern, “hip” offering, hip in more ways than one:

A little golf. A little oil painting. Later — a slimmer figure!

Don’t take our word for it. Pony up your $3.88 for Item 56 F 5965— inflatable sauna shorts — and you too can knock inches off your hips and belly!

Comes in a wide range of colors never before seen in nature.

That’s all for today, folks. If you’ve read this far, I hope you’ve enjoyed this latest installment of Fun with Old Medical Images. And, if not, we’ll be back with more grim pandemic news next time.

Chicken!

May 23rd, 2022

In Praise of Dr. Glaucomflecken

In the Ophthalmologist’s Office, 1930. William Sharp.

Sometimes there is someone so good at something that there is universal agreement we are witnessing something special.

Babe Ruth, Serena Williams, and Michael Jordan competing at their peaks. Charles Dickens or Jane Austen creating whole worlds out of invented characters and plots. Vladimir Horowitz performing Rachmaninoff at Carnegie Hall. Bernini creating sculptures from cold, hard marble that still take our breath away when we see them for the first time, 400 years later. Velazquez featuring himself and other onlookers in the greatest painting of all time (OK, my opinion), Las Meninas.

And, in the category of “Creator of Short Satirical Videos about the American Healthcare System,” we have Dr. Will Flanary, more commonly known by his stage name, Dr. Glaucomflecken.

Unlike my crowning the Velazquez painting the greatest ever, I’d argue this one is not just my opinion. It’s a fact.

Flanary’s short videos — featuring him (and just him) playing a variety of doctors, nurses, and administrators — have earned him universal praise from the medical community. We gobble up each release on Twitter or TikTok or YouTube, and rapturously respond with recognition about the eccentricities of our specialty, or the absurdities of American medicine. Often both.

How did a private practice ophthalmologist in Portland, Oregon, become the universal spokesperson for frustrated clinicians everywhere? As noted in a recent profile, he was always funny — doing stand-up comedy before medical school, contributing to a satirical medical site, posting on Twitter.

Then he nearly died — literally — suffering ventricular fibrillation at home in May 2020. Fortunately, his wife performed CPR until EMTs arrived, and he underwent placement of an implantable defibrillator during a short hospital stay.

But this experience didn’t only leave him with a lifesaving device. It also gave him first-hand experience navigating the insane complexities of the U.S. healthcare system, one so Byzantine that people who move here from Canada or Europe shudder at the prospect of dealing with it. Flanary took out his frustrations by skewering the system in his short videos, which have a gargantuan following.

Some choice examples: Prior authorizations. Hospital budget cuts. Academic publishing. The medical residency match.

How popular has he become within the medical community? He has over 1.5 million followers on TikTok, more than half a million on Twitter — that’s a lot. He’s the commencement speaker for today’s Yale School of Medicine graduation, quite the honor! I’m hoping to interview him for our inaugural podcast on Clinical Infectious Diseases, but not sure he will have the time — the invitation is currently sitting in his email inbox.

However, maybe he ultimately will agree to the interview, because he seems to have a soft spot for our quirky specialty. In these videos, watch him quite brilliantly capture our penchant for obsessive histories, long notes, and responsible antibiotic prescribing — and never once does he make fun of us for not doing any surgical procedures. Enjoy!

1. Medical student arrives for his ID rotation.

Hanging out with the infectious disease specialist pic.twitter.com/TctBhVf2CF

— Dr. Glaucomflecken (@DGlaucomflecken) March 4, 2021

2. Ace your interview for ID fellowship.

3. How to think like an ID doctor.

The Closer pic.twitter.com/jpNaI0PyNn

— Dr. Glaucomflecken (@DGlaucomflecken) May 16, 2021

4. … and let’s finish with a timely one.

Don’t say I didn’t warn you pic.twitter.com/YrTEwLbTka

— Dr. Glaucomflecken (@DGlaucomflecken) May 21, 2022

May 12th, 2022

As They Say, “Some Personal News”

Growing up, I had a dog who looked exactly like this — his name was Rufus. Maybe they are related.

This week marks the 14th anniversary of HIV and ID Observations, give or take a few weeks. I started writing this blog* in 2008 — and since then there have been 832 posts, a gazillion comments, and one awful (and ongoing) pandemic. For the opportunity, I sincerely thank Matt O’Rourke, a wonderful and generous editor at NEJM Journal Watch who took a chance on me when I proposed writing it.

(*The word “blog” has a mixed reputation at best, implying to some a venue for shallow navel-gazing and trite philosophizing. Milt Weinstein, one of the smartest people I know, told me flat out, “I don’t read blogs.” But what’s the appropriate alternative name? If we were in print, it would be a “column,” but we’re not in print and never have been. Many now call their regular writing a “newsletter,” but that implies a freestanding and often paid subscription service, which isn’t the case either. Help!)

Since it started all those years ago, this has been a place where I can write about pretty much anything ID-related (and sometimes not so ID-related). Matt moved on and up within NEJM Group, so I’m now guided by three different and skilled editors — Kristin Kelley, Amy Herman, Kelly Young (and previously, Catherine Ryan) — who take turns correcting wayward text and making sure my hyperlinks work. They only veto something if I choose a video that doesn’t meet the site’s family-friendly standards.

I’ve tried to keep the content relevant to clinicians, the tone casual and friendly, and the images and videos fun.

And I must thank you, the people who read this thing, and who make up a friendly, curious, and interesting community. Your feedback — in the comments section, or via emails, or directly — has been hugely gratifying on multiple levels. It’s wonderful to hear that my summary of some ID issue (length of antibiotic therapy, whether to wear white coats, drugs with good oral absorption, all those streptococci, to name a few) is useful, or entertaining, and preferably both! Plus, by having a moderated comments section, we’ve mostly avoided the vitriol that pops up regularly in these sorts of forums and on social media. COVID-19 stresses us all, but it should be no excuse to attack one another.

You might wonder why I’m making these reflections today — who celebrates a 14th anniversary? It’s because this week, I start handling submitted papers to Clinical Infectious Diseases (CID) as their incoming Editor-in-Chief, with the full transition taking place in July. It’s an exciting new challenge, one that certainly will take up a ton of time.

How much time? Just ask the current Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Robert “Chip” Schooley. He navigated this important ID journal through an unbelievable deluge of submissions during a global pandemic. The word “surge” as it relates to COVID-19 does not only apply to case numbers — it also applies to the volume of ID-related research papers, which have absolutely skyrocketed. Over on PubMed, the site lists over 250,000 COVID-19 papers since 2020 — and remember, before this date there were none. That came on top of an already high volume of submissions to this journal for non-COVID research in infectious diseases.

(Speaking of Dr. Schooley, I strongly recommend this profile of him in the San Diego Union-Tribune — it accurately captures his wide-ranging expertise and remarkable humanism.)

When friends and colleagues heard that I was taking this new position, one of the most common questions I received was “Will you still be writing the blog?”

The quick answer is “Yes.” This is an enormously gratifying creative outlet for me, in ways I never could have imagined when I started 14 years ago. Because of my new role, though, posts might be less frequent, or more related to content CID publishes (it is a highly relevant journal for all clinicians, not just ID doctors), or something else entirely. Into the great unknown…

Meanwhile, here’s an aptly named video site for an ID blog (there’s that word again). “ViralHog,” indeed. Certified family-friendly.

But tell me — what’s the dalmatian doing? Is he the referee? Certainly has the right colors.

(Watch in full screen and with sound on for full effect.)

May 4th, 2022

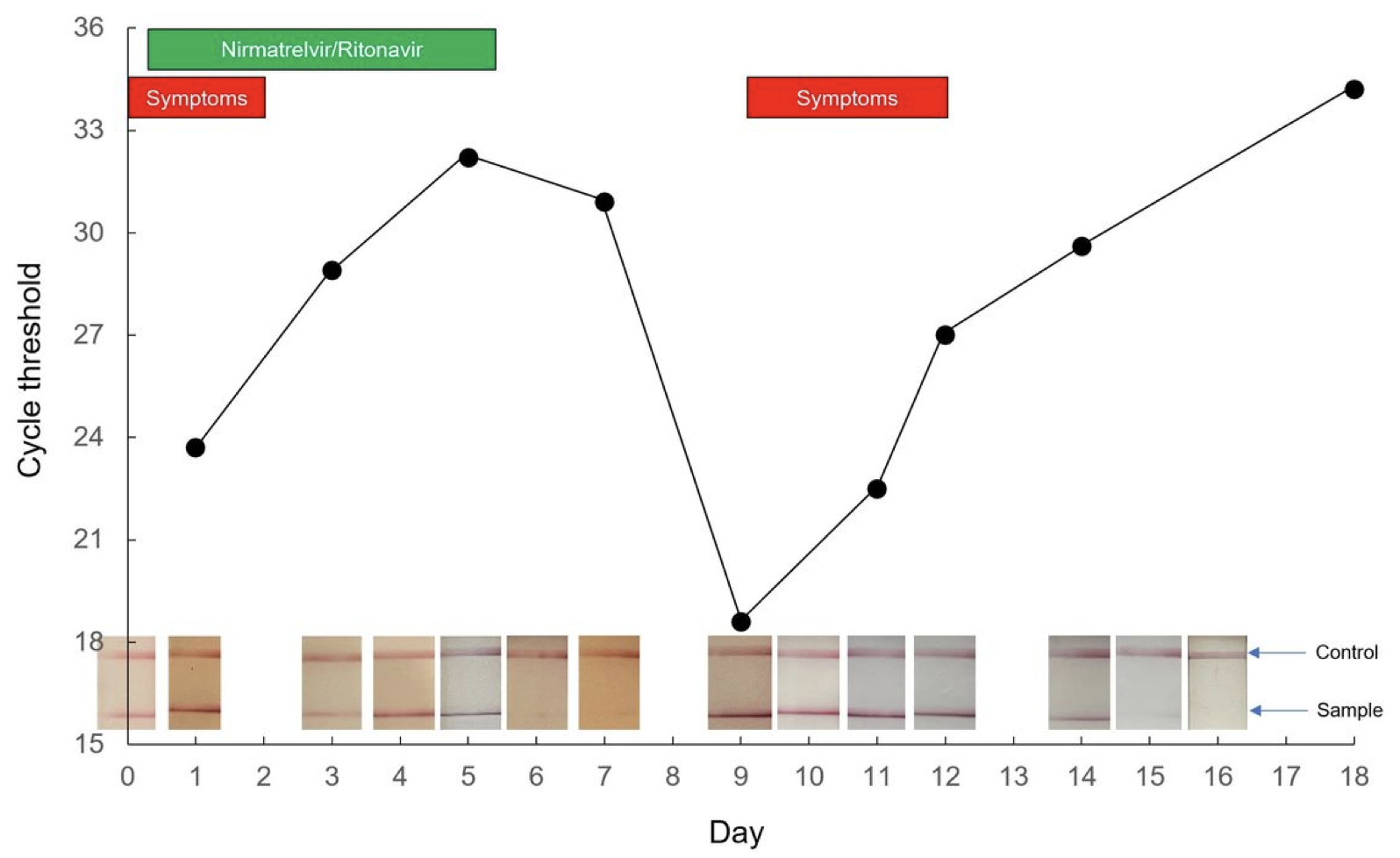

More on Relapses after Paxlovid Treatment for COVID-19

Unless you’ve been hiding under a rock, you’ve heard that some people treated for COVID-19 with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid) experience a relapse in illness shortly after stopping treatment.

It’s both a recurrence of symptoms and a positive antigen test — sometimes after the test became negative. One case report published as a pre-print shows that a relapse can have a very low cycle threshold, meaning a high viral load:

Relapses vary in severity, from very mild and brief to worse than the initial illness. Check out the comments in my previous post for a sampling.

Some posit that the immune system doesn’t get a chance to mount a full response since the drug quickly reduces exposure to viral antigens. Others note that certain individuals experience prolonged viral replication, symptoms, and antigen test positivity, and perhaps it’s this group that’s destined to rebound after the 5 days of Paxlovid use. The drug knocks down replication for a while, but not long enough, so it rebounds.

Maybe it’s both — these aren’t mutually exclusive hypotheses. Regardless, as noted in my prior post, there’s still plenty we don’t know. But given the rapidly increasing use of Paxlovid nationally, I thought it worth this brief update about two important things we’ve learned since then, plus my opinion on a commonly asked question about contagiousness.

First, Pfizer offered additional details from their EPIC-HR study, citing that late viral rebounds occurred in roughly the same proportion of treated and untreated participants in their trial — around 2%:

UPDATE: Pfizer gave me the figures regarding the proportion of people who had Covid rebound in the Paxlovid clinical trial: About 2% of participants who got the drug experienced rebound, compared with ~1.5% of those who received the placebo rebounding within the same time frame.

— Benjamin Ryan (@benryanwriter) April 28, 2022

Whether the rate of relapse is higher than this 2% in clinical practice is unknown. Certainly, it seems that way — it even happened to a famous virologist! — but without knowing the denominator of total treated patients, we can only speculate.

And remember, clinicians have noted biphasic illness patterns since the start of the pandemic, and continue to do so. We’ve attributed that second period of worsening mostly to a robust (and sometimes hyperactive) immune response, but potentially there could be a component of concomitant heightened viral replication.

Second, in communications with clinicians, the FDA and Pfizer have made it clear that the people who relapse are in fact eligible for re-treatment under the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA). In other words, the within-5-day symptom clock starts over with the relapse. This would be justified clinically for our highest-risk patients (severely immunocompromised, medically fragile, or with severe recurrent symptoms), and favored over other outpatient treatments (all of which have logistical or efficacy issues) until we know more. So far, viral resistance has not been identified.

So where does that leave us with regard to infection control issues? In my opinion, we should assume that people who experience a symptomatic relapse with a positive antigen test could transmit the virus to others. Until data prove otherwise — meaning studies show these late relapsers have defective virions that are not replication-competent — this should be the recommended approach for work, school, and socializing. Symptoms plus positive antigen test equals potentially contagious.

In the meantime, I completely agree with this editorialist that we should be doing more to monitor how Paxlovid is doing since the EUA launched. I’m hoping large healthcare systems can quickly assemble observational studies evaluating how often this relapse phenomenon occurs out there in what is often called “the real world” — which means, in this context, “not in a clinical trial”. Prospective studies collecting virologic and immunologic data would also provide great value, especially given the theoretical concern that treatment blunts a favorable immune response.

So let’s keep learning.

You know, baby steps.

April 25th, 2022

Yes, Relapses After Paxlovid Happen — Now What?

Young Monk in the Greek Style, from Mascarade à la Greque, Alexandre Petitot (1727-1801).

Around two weeks ago, one of my long-term, very stable patients with HIV called me saying she’d just been diagnosed with COVID-19. Over 60 with hypertension, and overweight, she qualified for nirmatrelvir/r (Paxlovid) under the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA), and took it without problem.

(Certain details changed for confidentiality.)

In fact, she started to improve within 24 hours of the first dose. Complained a bit about the metallic taste, but was thrilled at this rapid recovery.

She then contacted me again a week later, saying she’d relapsed. More nasal congestion, cough, and fatigue — not as bad as when the illness started, but unmistakably a relapse. Not only that, the home antigen test, which started out as a dark line at the outset, became a barely discernible line after the treatment, and now was clearly positive again.

Her biggest concern was getting back out in the world without infecting someone. She really wasn’t that sick; she just wanted advice about when she could return to work and start socializing again.

“Avoid close contact with others until that test clears,” I said. (Which it did a few days later, and she completely recovered.) But certainly the whole thing was a head-scratcher for both of us.

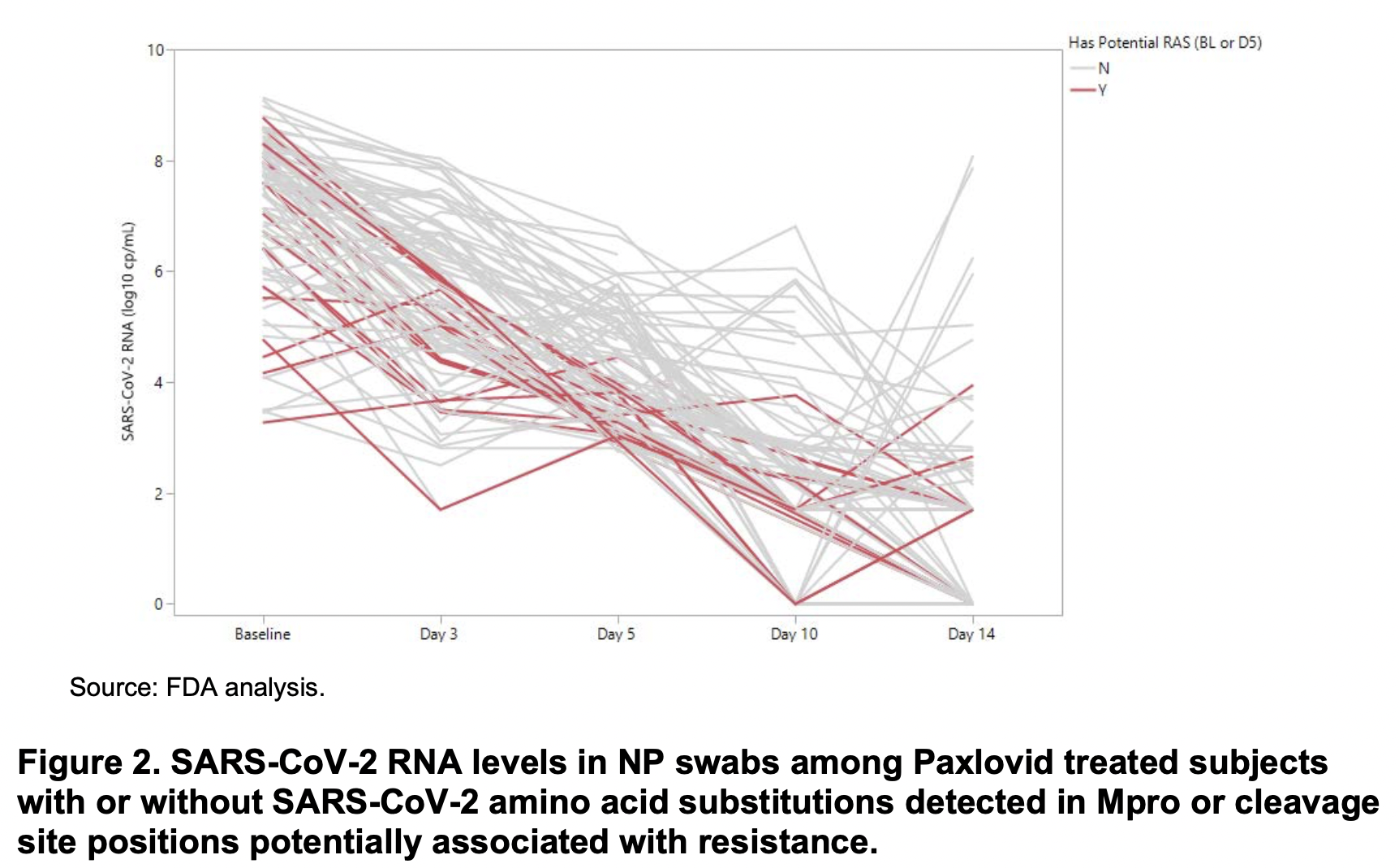

Turns out these relapses do occur; this was just the first time I saw it. The investigators from Pfizer observed them in their clinical trial EPIC-HR, and reported it to the FDA. Take a look at this figure from their study, which was not included in the NEJM paper, but did appear in an FDA report:

See those lines heading upwards from day 10-14? Those are relapses. Sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 from these cases did not demonstrate resistance mutations either at baseline or at relapse that correlated with resistance. Specifically:

In summary, currently there are no clear signals of baseline or treatment-emergent NIR resistance from the preliminary analyses of clinical trial EPIC-HR. These analyses will continue to be conducted as more complete data from EPIC-HR are obtained and reported.

A detailed analysis of a similar relapsing case is available as a pre-print — viral sequence the same at 3 time points (no resistance or reinfection), respiratory multiplex PCR negative (no new pathogen), good antibody response.

Not surprisingly, as use of Paxlovid increases along with the supply, the anecdotal reports of these relapses increase in parallel. Not just in clinical practice — they’ve popped up on social media and in the press. It’s now become a standard part of my counseling to people, that this return of symptoms and test positivity might happen.

So we know that relapses happen. What don’t we know about these cases? Quite a bit, actually.

- How often does it occur? It’s tricky from the figure to get a clear picture of the numerator and denominator. And of course, that was in an unvaccinated, high-risk population. What about those who are vaccinated?

- What are the risk factors? Could it be that those with baseline high viral loads/low cycle thresholds are at greater risk of relapse? People who are severely immunocompromised? Older? With some variants more than others?

- Does antiviral treatment blunt a helpful immune response? Does the immune system need to see a certain concentration of viral antigens to provide adequate clearance? Or are those who are relapsing just the subset of people who would have had prolonged viral shedding to begin with?

- Should we assume that people who relapse become contagious again? That’s my assumption — and it seems highly likely — but it’s worth proving in a research lab that these viruses are just as replication-competent as the pre-treatment viruses.

- Does the virus develop resistance during this 5-day course? So far this hasn’t been reported in a relapsed case, at least a far as I know. Seems inevitable at some point, however, so worth looking for, again in the context of a research study.

- Should treatment courses be longer? Maybe a longer course is better, but maybe not. How about a 5- vs. 10-day blinded clinical trial, with clinical, virologic, and immunologic endpoints? (Importantly, both 5- and 10-day courses follow the rules.)

- Does this happen with other antiviral strategies? I don’t recall hearing similar patterns with remdesivir or molnupiravir, but then again viral load reductions were less robust. This could be related to the mechanism of action of viral protease inhibitors.

- Should highly vulnerable people with relapses be treated again? Somehow “do nothing” for the most at-risk people with COVID-19 (for example, those on rituximab) doesn’t seem right when we have treatment tools at our disposal. One of my colleagues pointed out to me that neither repeated courses of nirmatrelvir (something I suggested in the above-linked Boston Globe piece) or treatment with molnupiravir would be allowed under the EUAs, as they must be within 5 days of symptom onset. It’s likely also that the bebtelovimab window of treatment (7 days) would be exceeded. That leaves 3 days of IV remdesivir as the only outpatient treatment option, which is very hard to access.

Given all these unknowns, it would be enormously helpful for Pfizer to release further data on their relapsing cases. Not just how often they happened, but also how they did clinically — presumably they did well, given the overall favorable results from the study. Any further information on immune responses? And did they paradoxically have a longer time to viral clearance than the placebo arm?

Fortunately, I’m aware of several research groups who are studying these cases right now here in Boston, and undoubtedly others are doing so elsewhere. We should know more soon.

But what we do know now — and I’ll keep saying this again and again — is that this is one tricky virus, full of surprises.

April 12th, 2022

Should We Prescribe Nirmatrelvir/r (Paxlovid) to Low-Risk COVID-19 Patients?

I usually put a clever caption below these vintage public health posters, but can’t think of one. Happy to take suggestions!

The top recommended treatment for high-risk outpatients with COVID-19 in the NIH Guidelines is nirmatrelvir/r (Paxlovid). It’s quite clear why.

In the EPIC-HR study, unvaccinated people at high risk for severe outcomes had an 89% reduction in the risk for hospitalization or death compared to placebo. If we just look at mortality — another important endpoint, don’t you think? — nirmatrelvir/r beat out placebo by a score of 0 (nirmatrelvir/r) to 13 (placebo).

Let’s add to this very favorable outcome several other benefits:

- The reliable activity against all variants

- The relatively good safety profile

- The short course of treatment (5 days)

- The substantial reduction in viral load, the most of any drug tested to date

- That it is pills rather than an IV

Yes, folks, we have a winner! Sure, it has lots of drug interactions and it tastes terrible, but it’s far and away the best choice out there right now.

So if we recommend this treatment for high-risk people with COVID, what about for symptomatic people who are not at high risk? Not now, but imagine a time when we had sufficient supply. Should we also recommend it for them?

I thought the answer was straightforward, and will give my views below. But I had an inkling that this wasn’t so clear a few weeks ago when one of my smart colleagues held the opposite opinion.

To test these choppy waters, I posted this poll online:

Let's suppose there's an ample supply of nirmatrelvir/r (Paxlovid), and you can prescribe it for anyone with symptomatic COVID-19. Cost not an issue. Based on what we know today, would you do so for "low-risk" cases? Why or why not?

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) April 10, 2022

Wow. Not only is there a pretty even split, but responses are so interesting, and quite strongly held. It’s fascinating to read them.

(And, by the way Dr. Titanji, good call.)

My own view? Given sufficient supply — and we’re not there yet — I’d certainly recommend nirmatrelvir/r even for low-risk symptomatic people. The motivation lies in the already summarized favorable results of the high-risk study, and hinted at even in the interim analysis of EPIC-SR, the study in low-risk people.

Remember, some low-risk younger people get severe disease. (Here’s a notable recent example — speedy recovery!) The reasons are poorly understood why this happens to some unlucky few (OK, not understood at all), and it’s rare, but all of us have seen these unfortunate cases. Could nirmatrelvir/r reduce the risk for severe disease even in this population?

Highly plausible. Look at the interim results of EPIC-SR which, though not showing benefit in the primary endpoint of time to symptom resolution, did appear to yield clinical benefits for this prespecified clinical endpoint:

A further advantage is the virologic response, which should reduce the likelihood of onward transmission. For those needing negative antigen tests prior to returning to work or school, it’s another plus to hasten this process.

Also, there’s the theoretical benefit that treatment will reduce the risk for long COVID, or other prolonged post-infectious symptoms. Both most certainly occur in people at low-risk for severe disease. Since at its genesis these are virus-induced complications, it’s not crazy to think that inhibiting and shortening viral replication will make these dreaded outcomes less likely. It will be challenging (and take some time) to prove, but it’s an important part of the research agenda.

Finally, treating symptomatic COVID-19 falls right in line with the first principles of our specialty. If there’s a safe, effective, and readily available treatment or prevention strategy for a symptomatic infection that is potentially serious, we treat it — even if most people will do fine.

I’m not alone in my view, obviously — 52% of respondents agreed. One respected ID researcher (who recently experienced her own household outbreak that was “not fun”), emailed me:

I agree with you 100%! I almost commented on that poll to say I thought it was a no-brainer but then saw how many people disagreed and stayed quiet! If it cuts short viral replication, the impact on secondary transmission could be enormous — far more than our vaccine responses are doing. What a huge benefit that could be!

The opposing view says it’s not yet been shown to benefit this population of lower-risk people. That these clinical endpoint results are “fragile” — so few outcomes that it could be an accident (and maybe motivated the increased sample size in the EPIC-SR study). That even if there is a clinical benefit, the number needed to treat will be gigantic. That resistance may develop. That the reduction in transmission effect isn’t proven. That there are places that don’t have this treatment at all, and our indiscriminate prescribing of nirmatrelvir/r will prevent it from being available abroad.

Lots of echoes of the oseltamivir controversies over the years. These are valid concerns, all of them. So I really do get this opposing view.

It’s just not mine.

What do you think?