An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

June 15th, 2023

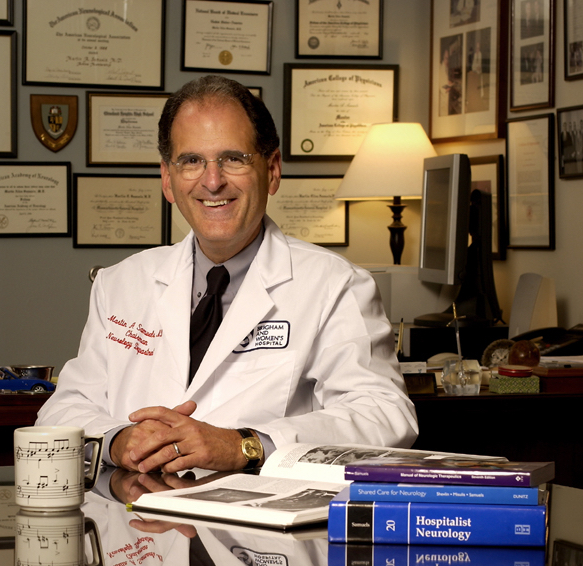

Clinical Teaching at the 99.9th Percentile: Dr. Martin (Marty) Samuels

One of the true joys of practicing at academic medical centers is working alongside great clinical teachers.

One of the true joys of practicing at academic medical centers is working alongside great clinical teachers.

No one exemplified this talented group better than Dr. Martin (Marty) Samuels, former chief of neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (where I work), and professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School. He was quite simply the best clinical teacher I’ve ever encountered.

Marty died last week, and our world is sadly now a less interesting and less fun place. What made him so special? Here are a few thoughts:

He had endless enthusiasm for clinical neurology. You could just see his eyes light up when a resident presented him a case. The combination of clinical problem solving together with a group of trainees eager to learn visibly energized him.

And the enthusiasm didn’t end with neurology. He embraced all of medicine, including its history, which he loved to connect to neurology — cardiology, nephrology, hepatology, ID. Watch him discuss a case of an older man with mental status changes during a “virtual” Neurology Morning Report, done on Zoom during the pandemic. He deftly describes his clinical reasoning, interweaving Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, pathophysiology, and his experience working with the great British hepatologist Dame Sheila Sherlock.

Note also the natty cartoon Dalmatians bow tie, both very New England-academic and very mischievous at the same time. So Marty.

His lecture topics often had simple titles: Dizziness. Headache. Dementia. Weakness. But they were hardly simple. No one who has heard his talk on dizziness forgets the first thing to do when a patient says they are dizzy. Namely, you pause, and repeat back — Dizzy? — and let them explain what they really mean!

He always knew his audience. One of the most difficult skills for clinician-teachers is explaining complex topics to people outside their field. (For you ID/HIV docs out there, just try to summarize the available antiretroviral agents. Ouch.) Experts routinely forget how to communicate with non-specialists — they are so immersed in their work that they assume everyone understands their arcane language.

Not Marty. He intuitively pitched his talks at the perfect level for the learners. You came away knowing that he was a true expert, but you were never baffled (or bored) by minutiae or jargon.

I have given a talk to the medical residents on, well, how to give a good talk. (I hope it’s a good talk!) Here’s one of the slides, with the Key Message repeated 4 times for emphasis — it’s that important:

Marty embraced this principle better than anyone.

He never let technology take center stage. Marty’s slides were often bare bones, just a few lines of text. His lectures were about what he was saying, not what he was showing. I heard him speak on dementia at a large medical education conference when the slide system failed; there were hundreds of clinicians in the cavernous conference hall. No matter — he held them spellbound with just his extemporaneous comments, presenting a few clinical cases and how he’d approach them. Everyone left with a clinical pearl they could apply to their practice.

If anything, Marty’s talks were better without slides. Anyone eager for a refresher on how to do the neurologic examination can find a 7-part (!) series on youtube, just him and a sample patient — no slides. Here’s a brief clip.

He wasn’t shy about expressing his opinion. Marty was the longtime editor of NEJM Journal Watch Neurology, so we attended several editors’ meetings together. One memorable time, the assembled (myself included) were trading ideas about how to keep up with the ever-growing volume of research, citing newer (at that time) techniques such as listservs, signing up for electronic tables of contents (“eTOCs”), and message boards.

Marty didn’t participate in the discussion — until finally, he said, “Isn’t it more important that we get it right, rather than get it fast? Because I confess this entire conversation fills me with a profound sense of ennui.” That ended the discussion!

He deeply distrusted “systems” that attempted to interfere with clinical care in the name of efficiency for efficiency’s sake or, even worse, just to save money. He found it particularly ironic that many of the very people espousing such systems would, when confronted with an illness in themselves or their family, immediately try to circumvent the system they had created.

He wasn’t shy about giving a name to this practice, either — specifically, hypocrisy. I encourage you to read the linked post, it’s a classic.

He wasn’t afraid to share the fact that he made mistakes. We all make mistakes — we’re human, after all — and Marty believed that these mistakes make us better clinicians when we think through why we made them, and what we can learn. One of his very best talks even had the title, “What My Mistakes Taught Me”, and he commissioned a bunch of us to come up with similar talks. What a challenging exercise!

He likened these mistakes to the genetic errors that get weeded out through evolution. We don’t try to make a mistake — but they happen. We acknowledge it. Analyze why it happened. We then learn from the error, with the goal of not making that mistake again.

Evolution at work.

He was funny. So very funny. A colleague recently told me that Marty did stand-up comedy after graduating from college, and I’m not surprised — his timing was perfect. I remember he gave medical grand rounds several years ago, and began it with a particularly good joke, but one that would easily qualify as “blue” humor. Let’s just say that my editors here at NEJM Journal Watch would never let me repeat it in this post.

After he got a big laugh (and he always got a big laugh), he looked at us and said, “That joke has nothing to do with my lecture. I just wanted to see if I could get away with saying it in front of the Dean of Harvard Medical School, who I knew would be attending today.”

Even bigger laugh.

Wrapping up, I can do no better at showing what a captivating speaker he was than to share this talk he gave just over a decade ago at an ethics forum run by the Massachusetts Medical Society — our publisher. It’s an excellent use of 25 minutes of your time, but if you’re busy, start at 16’43” when he presents a case he saw for discussion.

Rest in peace, Marty. We’re really going to miss you.

June 8th, 2023

Fifteen Years Later, Why I’m Still Writing This

Image by Angeles Balaguer from Pixabay

Seems like just yesterday that my wonderful editors at NEJM Journal Watch helped me write a piece marking this site’s 10-year anniversary.

But no — that was 5 years ago. Yikes.

Let’s see, what happened since the spring of 2018 that is relevant to this place:

- 216 posts. According to our crack research team, that’s one every 8.449074 days.

- 2,138 comments. Most of them nice, helpful, interesting. Wonderful community here.

- 13 polls. The one with the most votes in the past 5 years involved syphilis testing — a quintessential ID poll, isn’t it? Should doctors still be allowed to wear white coats? is still the all-time winner, from 2015.

- No more Physician’s First Watch. I can’t begin to describe how much I miss this reliable and insightful summary of medical news, delivered daily — what a great service. Not only that, they were also kind enough to link to my posts on a regular basis, greatly increasing and diversifying the readership. I wish it were back!

- There was a global pandemic. Oh yeah, that. Note the date on that syphilis poll, January 2020 … <<involuntary shudder>>

It’s this last item which makes the current look back so different from the first one. Something momentous and literally world-changing happened during the past 5 years — and, like it or not, we ID specialists were front and center in the response, right from the start. 15 million deaths later, that’s got to hurt.

I thought of this recently when Medscape published one of its physician polls, this one on Lifestyle, Happiness and Burnout.

The results? While all physicians experienced a decline in happiness compared to pre-pandemic times, ID physicians have dropped a ton, falling to the bottom of list.

In a @Medscape survey, ID physicians experienced a large drop in self-reported happiness comparing pre-pandemic to now, and we find ourselves at the bottom of the list.https://t.co/4VzU7O7XRH

1/3 pic.twitter.com/sJqDTLmjCy— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) June 4, 2023

We can quibble with the methodology. Only 90 ID doctors surveyed! How representative of the specialty can this be? And the differences between many of the specialties are marginal. But I still believe the results mean something — namely that we’ve taken a big hit.

Which brings me back to one of most common questions I still get about writing this blog, which is Why do you do it?

Some of the answers are the same as what I posted 5 years ago — namely, that it’s fun, it’s a chance to write in my own voice rather than the voice of academic medical journals, and my editors let me be alternatively serious and silly without batting an eye over the dog, baseball, or comedy videos.

But also now, after we’ve passed the worst of the pandemic (crossing fingers), it’s a chance to highlight the continued joy and excitement of the specialty of Infectious Diseases — a field which, for all its problems, remains endlessly fascinating and rewarding. Again, I’ll cite this magazine feature on the practice of ID featuring Dr. Jerome Levine. His words:

Never once in all my years of practice have I ever been bored.

I’m pretty sure this comment resonates with ID doctors everywhere. How many clinicians are lucky enough to feel this way about their specialty? Describing this dynamic world of ID is the primary reason I continue to write here, whether it’s a Link-o-Rama, a Really Rapid Review™, talking through a clinical dilemma or controversial study, ranting about a commonly held annoyance, or just getting a chance to post some ideas floating around in my head.

So as long as you keep reading it, I’ll be writing it. Hope I’ve conveyed — and continue to convey — some of that joy.

And speaking of videos, how about this catch? It just might be the most remarkable one in the history of professional baseball.

Got to love his face after the catch. Had it all the time.

June 2nd, 2023

Continued Activity of NRTIs Despite Resistance Is a Real Thing

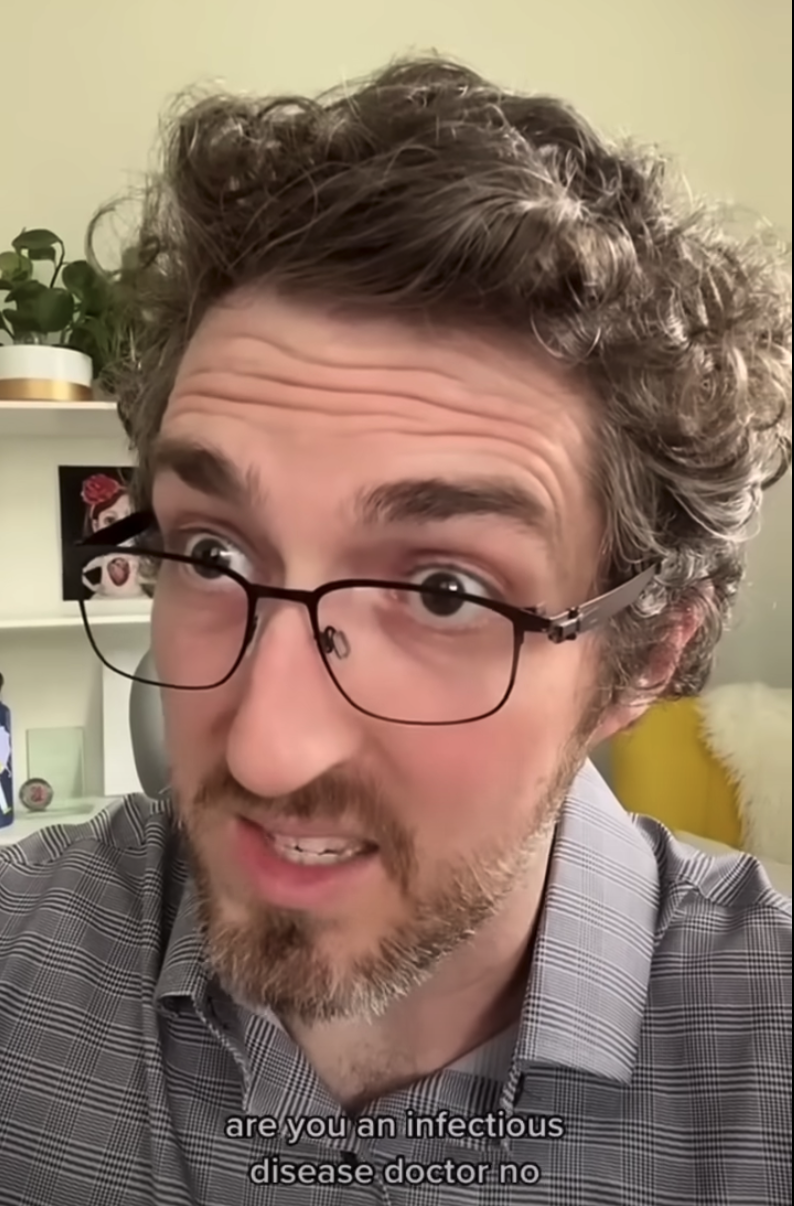

I don’t think many orthopedists are reading this post.

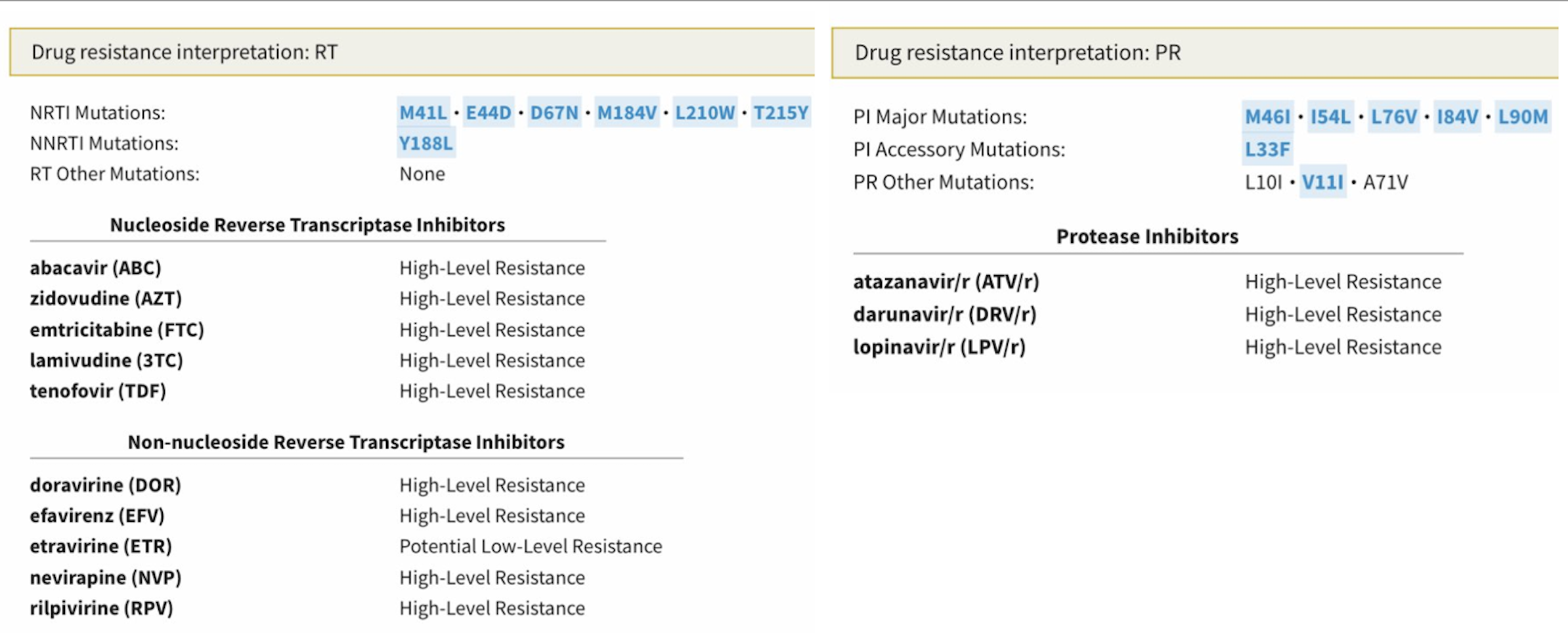

In our last post, we reviewed a case of a person with longstanding HIV with extensive multi-class resistance, but now a decade of viral suppression. They’re currently on an HIV treatment regimen of fully active raltegravir, partially active etravirine, and barely active (or not active at all!) darunavir. There are no NRTIs in the regimen, presumably because a resistance genotype showed four thymidine-associated mutations plus M184V.

They are taking a lot of large pills (four twice daily), with significant drug interactions and metabolic adverse effects, and the challenge is whether or not to simplify — and to what.

Based on the poll results, the comments, and the conversation online, there was hardly unanimity. But here’s what I would have voted:

It’s OK to simplify to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir AF (BIC/FTC/TAF) — or, if you don’t have it, tenofovir/lamivudine/dolutegravir (TLD).

This isn’t the only effective choice. There are other active drugs from newer drug classes (ibalizumab, fostemsavir, lenacapavir), one of which could be added to BIC/FTC/TAF or to TLD. And of course they could just stay on what they’re on — if it ain’t broke, right?

(Quick aside — some recommended regimens with doravirine or continued darunavir. Based on our understanding of genotypic correlates of drug resistance in these two drug classes, I strongly doubt these two drugs will do much of anything — with the Y188L mutation, I’m especially dubious about doravirine.)

The BIC/FTC/TAF or TLD options are highly likely to maintain viral suppression, plus they offer several obvious advantages — simplicity, relatively low cost, fewer adverse effects or drug interactions. The reason why they will work is the focus of this post.

First, it’s because bictegravir and dolutegravir have a much higher resistance barrier than raltegravir. There’s no SWITCHMRK study in their profile — just the opposite, with switch studies in suppressed patients consistently showing maintenance of suppression, and no emergent integrase inhibitor resistance. To get resistance to DTG or BIC, you really need to put them through a stress test, often a combination of high baseline viral load, low CD4-cell count, suboptimal adherence, monotherapy, or drug interactions.

None of those apply here.

Second, and sometimes not well appreciated, the NRTIs continue to exert substantial antiviral activity even in the setting of significant genotypic resistance. In other words, despite that nasty-looking genotype with all NRTIs characterized as showing “high-level resistance,” we still get something from this drug class.

I’ve linked below a bunch of studies that directly or indirectly prove that this phenomenon is clinically important. Some were done in eras when treatment options were much more limited, and hence maintenance of the NRTI class was a high priority. Each one shows that ongoing NRTI activity in the setting of genotypic resistance is the real deal, not just some laboratory phenomenon:

- Discontinuation of 3TC in patients with known M184V and viremia leads to a significant increase in HIV RNA.

- In patients with viremia on combination ART, selective cessation of the NRTIs but not the PIs or NNRTIs leads to an increase in HIV RNA.

- In people with known M184V, 3TC monotherapy maintains HIV RNA lower and CD4 higher than stopping all ART.

- In people on second-line therapy known to have the M184V mutation, maintenance therapy with a boosted PI plus 3TC was superior to a boosted PI alone.

- SECOND-LINE, EARNEST, SELECT, STAR — Four studies of HIV treatment failure of first-line dual NRTI/NNRTI therapy show that “recycled” NRTIs plus a boosted PI work as well as raltegravir (a fully active second drug class) plus a boosted PI — and better than PI monotherapy.

- NRTI resistance mutations had no impact on the risk of virologic failure in patients switched to DTG+2NRTIs.

- For people on second-line therapy in Kenya with dual NRTIs and a boosted PI, switching to TLD was noninferior to continuing the boosted PI.

This last study, called 2SD, deserves further description; from the IAS-USA guidelines:

In the 2SD study conducted in Kenya, participants receiving second-line regimens consisting of a boosted PI plus nRTIs were randomly assigned to continue their current treatment or switch to dolutegravir plus 2 nRTIs. At 48 weeks, dolutegravir plus 2 nRTIs was noninferior to the continued therapy. Although no prior resistance assessments were performed in that trial, other studies of second-line boosted PI regimens in Africa have shown extensive nRTI resistance, including high rates of M184V and K65R mutations, and such resistance would be expected in the population enrolled in the 2SD trial.

Note also that the investigator presenting these data said that there was no INSTI resistance detected among those randomized to TLD. Awaiting the publications of this trial, we can also take some comfort in the fact that to date, I’m not aware of a single published report of the dolutegravir or bictegravir-based switch strategy failing in cases like this one, provided that adherence is good:

#IDTwitter–Aware of a case report or series of the following?

– Hx of known NRTI resistance and no INSTI resistance

– Suppressed on non-BIC or DTG ART w/ good med adherence

– Switches to BIC/FTC/TAF or TLD

– Develops failure w/ INSTI resistance despite ongoing good adherence?— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) May 30, 2023

Importantly, I’m not saying that bictegravir or dolutegravir resistance cannot happen. In the NADIA and DAWNING studies of second-line treatment comparing DTG plus NRTIs versus boosted PI plus NRTIs, although the DTG strategy turned out to be noninferior (and with DAWNING, even superior), a small number of participants did develop INSTI resistance. But remember, these were patients who were viremic on study entry, not virally suppressed; furthermore, baseline NRTI resistance did not appear to influence the outcomes.

One multinational cohort study does show that NRTI resistance is indeed a risk factor for development of DTG resistance, but there is insufficient data from the preprint to assess whether it occurred in people virologically suppressed or viremic when they started DTG. Nor does this preprint address medication adherence.

Fortunately, we should have more data to inform this decision shortly. A huge number of people on second-line treatment globally will be switching to TLD, and BIC/FTC/TAF is by far the most popular HIV regimen here in the USA, both for initial treatment and stable-switch.

Stay tuned!

And watch this wonderful video, which includes asking an orthopedist Are you an infectious diseases doctor? His response is priceless.

May 25th, 2023

The Legacy of a Disappointing HIV Clinical Trial — Does It Still Apply to HIV Today?

A long, long time ago, back in the early exciting days of raltegravir, the first HIV integrase inhibitor, we learned something important from a clinical trial with disappointing results. The trial bore the (barely) hidden name of the company that developed the drug — SWITCHMRK, get it? — and had a profound impact on how we managed virologically suppressed patients for years.

A long, long time ago, back in the early exciting days of raltegravir, the first HIV integrase inhibitor, we learned something important from a clinical trial with disappointing results. The trial bore the (barely) hidden name of the company that developed the drug — SWITCHMRK, get it? — and had a profound impact on how we managed virologically suppressed patients for years.

What did we learn? Namely, that it was risky to switch stable people from their “high resistance barrier” regimen of lopinavir/ritonavir plus NRTIs to raltegravir plus NRTIs if they harbored viruses with NRTI resistance. Some of the participants who had a history of treatment failure who switched ended up experiencing virologic rebound with integrase inhibitor resistance, which made the switch to raltegravir not noninferior (sorry for the double negative) to continuing lopinavir/ritonavir.

The interpretation was that despite the potency and excellent tolerability of raltegravir — massively better than lopinavir/ritonavir — it wasn’t enough to maintain viral suppression reliably unless the NRTIs were also fully active. Based on these results, for years we steered clear of use of this valuable drug class in any setting where we couldn’t use at least one other fully active drug.

(My friend and colleague Joe Eron was the lead author on this study. I will note once again that Joe easily makes the top-5 in smarts in the HIV research world, no exaggeration, and that this was a very reasonable study design at the time, negative results notwithstanding. Unrelated, I wonder if Joe will attend this June 4 minor league baseball game in Charlotte, called Joe-Nanza, which aims to assemble the largest number of Joes at any single sporting event in history. It’s just a 2-hour drive from Chapel Hill!)

So now that we’ve reviewed SWITCHMRK, and a special event featuring Joes, let’s fast-forward to today, and contemplate a case. I’m sharing it with permission from Dr. Jezer Lezama, an ID doctor from Mexico who was looking for help (case details slightly edited):

PWH multi-drug resistance, w/high level R to PIs, NRTIs, NNRTIs, only etravirine partially active in 2013 but w/o previous exposure to integrase inhibitors. Rescue Tx: DRV600/r BID + RAL + ETV with viral suppression since then. Simplify? To which regimen?

He provided the 2013 resistance genotype, and yes, this is a challenging virus:

There’s a lot there to digest, so allow me to provide a quick interpretation, sparing you the trip to the Stanford HIV Drug Resistance Database:

- NRTIs: The virus has the “TAM-1” pathway (M41L, L210W, T215Y), plus another thymidine-associated mutation (D67N), so even tenofovir activity is reduced. M184V, the magical 3TC/FTC mutation, partially reverses this tenofovir resistance.

- NNRTIs: For this drug class, we find the important Y188L mutation, which confers high-level phenotypic resistance to all NNRTIs except etravirine. Trivia buffs will recall that Y188L is present on HIV-2 isolates, which is why NNRTIs don’t work against HIV-2.

- PIs: Not much to like here — there are 3 major darunavir-associated mutations (I54L, L76V, I84V), two minor darunavir mutations (L33F, V11I), plus a couple of other major PI mutations (M46I, L90M). I bet there’s some fosamprenavir treatment failure in the past. If this person had a phenotype done, I suspect the fold-change loss of susceptibility would suggest that the darunavir isn’t doing much in this regimen, twice-daily dosing notwithstanding.

- INSTI: Not done, but presumably no resistance.

Fortunately, the brief history does give us good news about how he’s doing clinically — virologic suppression since 2013 on the “TRIO” regimen of twice-daily darunavir, twice-daily raltegravir, and twice-daily etravirine. As I’ve mentioned before, I cannot begin to describe how transformational HIV drug development was in the late 2000s, when we suddenly had these three new tools (especially raltegravir) for our highly-adherent PWH with multidrug resistance.

Some experienced an undetectable viral load for the very first time in their lives. It was truly a cause for celebration. Yay!

Dr. Lezama’s specific question now is — can he simplify the treatment to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir AF? Why or why not?

What do you think? Next week we’ll review the results.

May 15th, 2023

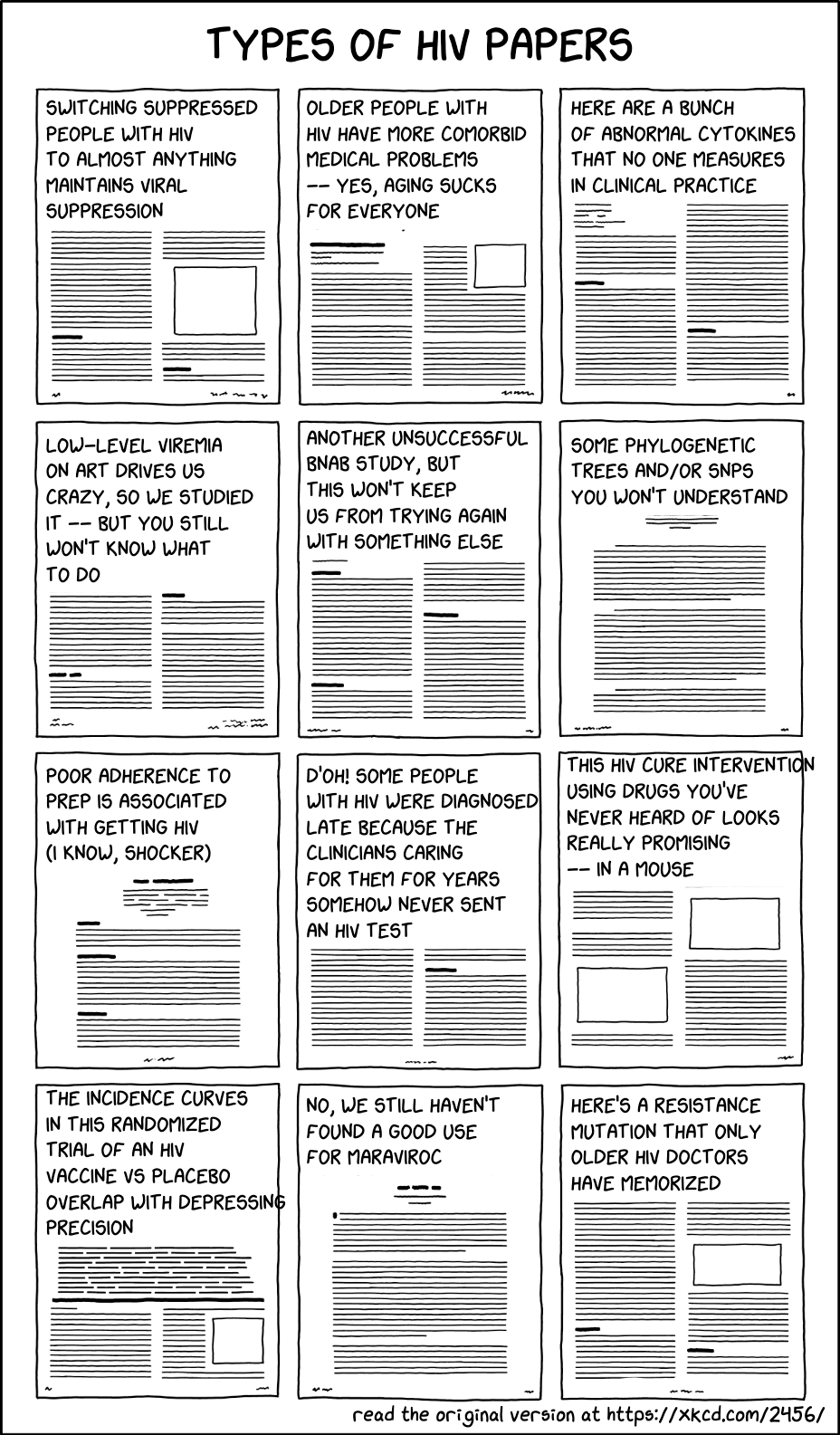

Types of HIV Papers — A Quick Guide

I spend a lot of my time reading HIV clinical research papers. A lot.

So here, for your viewing pleasure, is a poster I updated and modified from a brilliant xkcd web comic (using this tool), describing some common HIV clinical research themes.

Suitable for framing, it should prove helpful as you embark on your next research project.

A brief commentary on the contents of these papers:

- Switching suppressed people with HIV (PWH) on antiretroviral therapy (ART) to almost anything maintains viral suppression. This is true for both biologic and behavioral reasons: there’s no viral replication at baseline, and only people with proven good medication adherence are eligible to participate. That means if it doesn’t work — like the raltegravir plus maraviroc switch — it’s pretty bad.

- Older people with HIV have more comorbid medical problems — yes, aging sucks for everyone. Everyone! No exceptions to the rule, alas.

- Here are a bunch of abnormal cytokines that nobody measures in clinical practice. They’re abnormal, yes. Clinical significance? Ummm … let me get back to you on that one. Or let me ask someone who loves cytokines, like the innovative and wonderful Dr. Irini Sereti.

- Low-level viremia drives us crazy, so we studied it — but you still won’t know what to do. I’m lucky to work with a guru of low-level viremia (among other things), Dr. Jonathan Li, a translational virologist and senior author on this fascinating study. He knows more about this annoying lab result — its causes and implications — than anyone on the planet. Good to have his number on speed dial, if “speed dial” is still a thing in a post-landline age.

- Another unsuccessful broadly neutralizing antibody (bnAb) study, but this won’t keep us from trying again with something else. Let’s try an even broader one! One that’s more potent! Let’s “extendify” it, using techniques of “extendification”, so it can be given less often! Then it might work. But if not, we’ll try again!

- Some phylogenetic trees and/or single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that you won’t understand. Or at least, I won’t understand. Throw in a genomewide association study (GWAS) with a Manhattan plot, and let the confusion start.

- Poor adherence to preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is associated with getting HIV (I know, shocker). These are important studies from a behavioral health perspective, such as this recent one. But let me put this a different way — what if you had a strategy that clearly worked, but it wasn’t used? Would it still work?

- D’oh! Some people with HIV were diagnosed late because the clinicians caring for them for years never sent an HIV test. A remarkably common clinical error, even in 2023, sadly. Quoting this noted researcher in the title’s first syllable.

- This HIV cure intervention using drugs you’ve never heard of looks really promising — in a mouse. Or if not panobinostat, vedolizumab, or ipilimumab, how about some CRISPR?

- The incidence curves in this randomized trial of an HIV vaccine versus placebo overlap with depressing precision. Here’s the latest, alas. Oh well, it’s important to keep trying.

- No, we still haven’t found a good use for maraviroc. But still trying! Trivia buffs will know the clever brand name of this rarely used antiretroviral agent — Selzentry. Get it?

- Here’s a resistance mutation that only older HIV doctors have memorized. Guilty as charged. I’m still miffed that E138K is a resistance mutation for both nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) and integrase inhibitors. What’s up with that?

Ok, that’s a wrap. Am sure I left off some major themes, what else would you include?

Hey, dog lovers — is this you? (It’s definitely me.)

Greeting humans vs their dogs pic.twitter.com/NeGbEtd1n8

— Emma Pope (@emmerpope) September 21, 2022

May 8th, 2023

As the Public Health Emergency Comes to an End, How Are We Feeling About This?

As you no doubt heard, on Friday, May 5, 2023, the WHO declared the end of the global health emergency from COVID-19.

Here in the U.S., the federal public health emergency will expire on May 11. That’s Thursday, just a few days from now.

These events reflect two realities that, while seemingly contradictory, make these decisions reasonable — my constitutionally worried ID-doc mentality notwithstanding.

On the one hand, COVID is far from gone. Our patients, family, and friends are still getting this pesky bug, many of them now repeat episodes. And it always bears mentioning that, for certain people with weakened immune systems or multiple other medical problems, COVID is the cause, or the trigger, of severe illness. Some will get long COVID, though fortunately the incidence of this complication has declined over time.

Some worry about the increase in cases that will likely occur in the South as summer heats up and people move indoors. Or they are concerned about the most recent genetic offspring of Omicron, the scarily named Hyperion (XBB.1.9.1) or Arcturus (XBB.1.16).

All valid points. But let’s look at the other side of the current reality. Deaths due to COVID globally and in the U.S. have been below April 2020 levels and stable for over a year. The same holds true for hospitalizations for severe COVID-related illness.

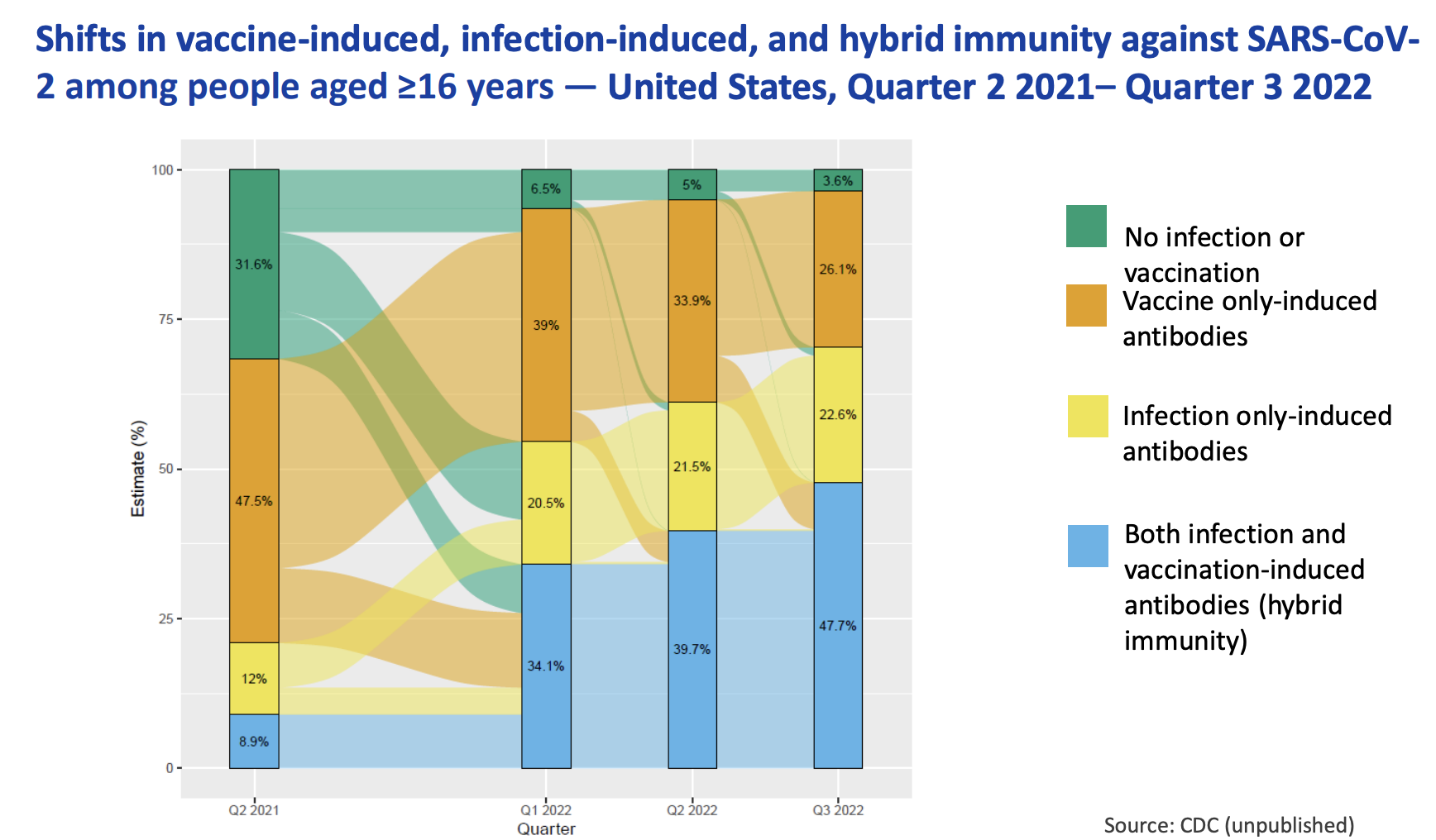

The cause? Widespread immunity, giving protection from severe illness:

By the end of 2022, an estimated 99% of the US population had some form of immunologic exposure to SARS-CoV-2 (infection or vaccination or both). https://t.co/7iioxJUG8h

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) May 2, 2023

If you don’t like that study, here’s the CDC’s version, which they presented last week:

So COVID isn’t gone. But it sure is different now.

Importantly, not gone also are innumerable other infectious threats, including RSV and influenza and tuberculosis and Lyme disease and malaria and Staph aureus and you-name-it. No global or federal emergency for them — though I suspect first-year ID fellows all think we should have one for staph.

The passing of the COVID emergency inevitably brings to us ID docs certain feelings and recollections, even if it’s just the creepy feeling that if we let our guard down this SARS-CoV-2 thing is going to pounce again.

Even writing that makes me nervous. To be concise, it’s a combination of relief and trepidation.

So … how are you feeling about this?

Interested in hearing from both the ID and non-ID community!

April 28th, 2023

What is the Future of HIV Primary Care?

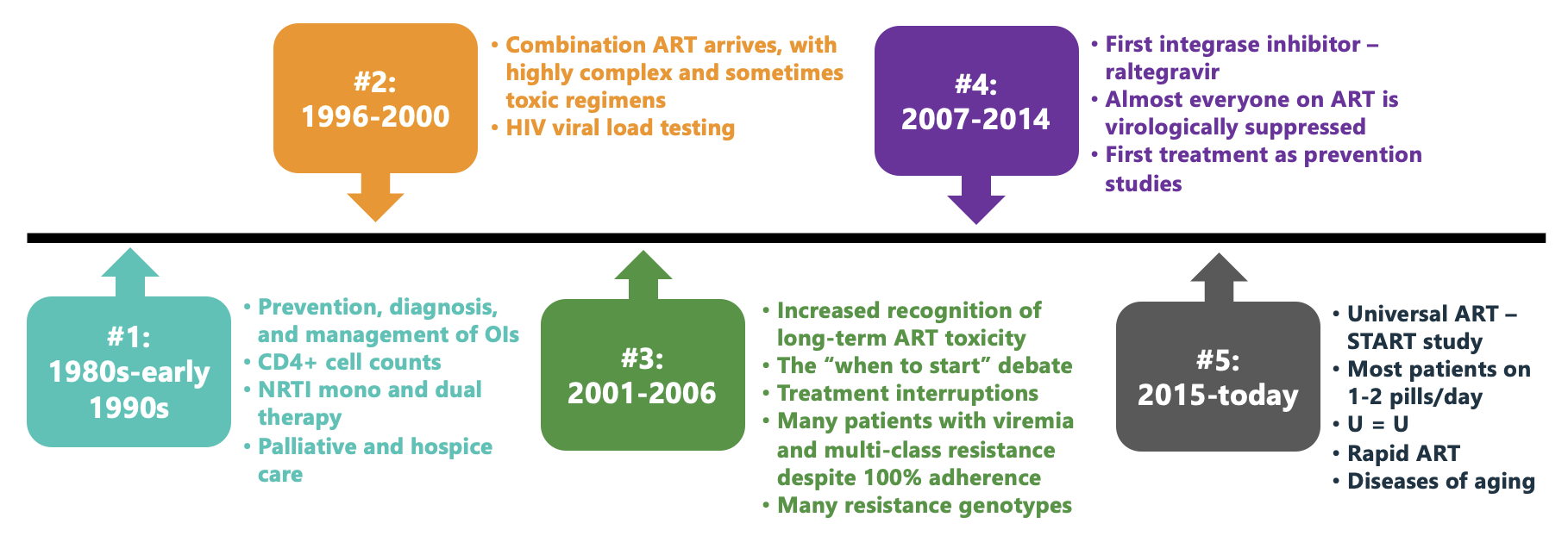

Here’s a figure I’ve made for an upcoming talk, which is entitled “The Future of HIV Care.” It summarizes several eras in HIV treatment, finishing up with the current unprecedented successful phase where most people with HIV take 1–2 pills a day, have virologic suppression and no clinically apparent immunodeficiency. HIV is often the least of their medical problems.

To put this into context, a patient at our hospital recently found out that the cause of their several months of fatigue and weight loss was HIV, and expressed relief that it wasn’t diabetes or cancer. And on hearing this comment, all the people on our HIV treatment team agreed that the management would indeed be easier, and more likely successful.

I don’t mean to diminish the potential severity of HIV, which of course can, undiagnosed and untreated, still be lethal. Far too many people in this country with HIV are either undiagnosed, or diagnosed and not engaged in regular care or treatment. Getting them on therapy remains an urgent individual and public health priority.

But for those in care, as an example of medical progress, HIV treatment stands out as a phenomenal success.

This success begs the question, once again, of the role ID specialists should play in the management of people who have HIV once they are on stable ART. When I last covered this topic here on this site nearly a decade ago, we were in the tail end of Era #4 above — and since then treatment has only gotten better.

For emphasis, I still believe ID doctors and HIV specialists should play a primary role in handling new HIV diagnoses, managing opportunistic infections and other complications, interpreting resistance testing, and helping guide treatment switches, especially as new options arise. The nuances of figuring out the best candidates for long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine certainly have put a recent premium on our expertise.

But the stable septuagenarian on one-pill ART whose major problems are hypertension, osteoarthritis, and, yes, type 2 diabetes? Who among us can claim that we’ve kept up sufficiently with these non-ID issues to be their ideal primary provider? If you, as an ID specialist, were given the option of attending an educational session from a brilliant speaker on “Advances in the Management of Invasive Fungal Infections” or “Advances in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes,” which would you choose?

We should not give up HIV care, but potentially shift it to be handled more like other medical specialties. Oncologists and rheumatologists, to cite two examples, play the dominant role in their respective diseases when treatments are active and monitoring is intense. But neither specialty takes on full primary care once the patients are rock-solid stable.

Pushing against any such distribution of HIV care to generalists is that most (importantly, not all) of the primary care workforce hasn’t been doing very much in HIV management. It’s notably concentrated in a very small fraction of U.S. clinicians. As an example, a patient of mine recently was told by their PCP that they wouldn’t order their routine monitoring tests — CBC, comprehensive metabolic panel, and HIV RNA — because “only ID can do that.” This is of course an extreme example (and certainly not true), but the anecdote shows how far from HIV general practice is for most people doing primary care.

Another important perspective comes from our patients, some of whom we’ve followed for decades. They may not be comfortable switching primary care, especially with a disease that still sadly confers some societal stigma.

So let’s re-do the poll and see what you think. As usual, I very much welcome in the comments section your opinions about this issue — and will select a few choice views for the talk!

Thank you.

April 21st, 2023

A Change-of-Season ID/HIV Link-o-Rama

Bug, from Martin Frobenius Ledermüller’s Microscopic Delights (1759–63)

The warm weather takes its sweet time to arrive here in Boston, teasing us with an occasional comfortable day, but reverting frequently to chilly temperatures and high winds until mid-to-late May at the earliest. The afternoon sunlight might say, “Spring is here!”, but the nightly temps in the upper 30s/low 40s definitely say otherwise. Brrr.

Anyway, here are a bunch of assorted ID/HIV links of note, as the weather in Boston can’t decide between winter and summer — and eventually will skip spring entirely, as usual:

- Postexposure prophylaxis with one 200-mg dose of doxycycline reduced the risk of bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Based on this and two other studies from France, there is little doubt this strategy works. The key will be implementing it in the right population, which for now appears to be men who have sex with men (MSM) or trans women with a history of recurrent or multiple STIs. And of course, long-term risks (resistance, other adverse effects) remain unknown.

- An experimental RSV vaccine given during pregnancy reduced the risk of “medically attended” severe RSV-associated lower respiratory tract illness in infants. This was one of the co-primary endpoints; the vaccine was not significantly better than placebo for any medically attended RSV-associated lower respiratory tract illness within 90 days after birth. An accompanying editorial appropriately describes the “complex policy decisions” about whether to offer this vaccine to pregnant women, as another RSV vaccine did show a signal of increasing the risk of premature birth — one not observed here.

- A large study of statin versus placebo in people with HIV was stopped early due to efficacy. Participants were at low-to-moderate risk of myocardial infarction (MI), and had stable HIV disease; pitavastatin reduced the risk of major cardiovascular events by 35%. One particular area of interest will be how strong the signal of benefit is across baseline characteristics — I suspect that relative risk reduction will be preserved, but for some, the absolute risk will be quite low, limiting uptake. But add this study to the “put statins in the water” team.

- Prophylactic piperacillin-tazobactam prior to pancreatoduodenectomy (better known as a Whipple procedure) reduced postoperative complications significantly more than cefoxitin. The study stopped early due to the large beneficial effect of pip-tazo (which is how I avoid saying the expired brand name). This is the kind of clinical trial for common clinical strategies in ID we should see more often! I strongly suspect this one will change clinical practice guidelines.

- HIV incidence was higher among men choosing event-driven rather than daily PrEP. An important paper given both the relatively understudied population (MSM in West Africa), and the results — adherence to the event-driven strategy was significantly lower, clearly influencing the outcome.

- In a randomized clinical trial, participants receiving fluvoxamine plus inhaled budesonide had fewer ER visits or hospitalizations or complications due to COVID-19 than those getting placebo. Note that the dose of fluvoxamine is 100 mg twice daily, 2 times higher than in the negative COVID-OUT study. These positive randomized clinical trials (see metformin) in people immunized and/or previously having had COVID-19 ironically offer more direct evidence of clinical benefit in this immune population than molnupiravir — and some would say nirmatrelvir/r as well.

- In Staph aureus bacteremia, combination therapy with cloxacillin plus fosfomycin was no better than cloxacillin alone. We’re still awaiting a combination therapy study that shows “more is better” for this challenging clinical entity. The study was presented at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, often abbreviated to “ECCMID” — which is rapidly emerging as one of the premiere clinical infectious diseases meetings in the world.

- A man died of rabies even though he received appropriate postexposure treatment. In this, the first report of such postexposure prophylaxis failure, the authors speculate that his immunocompromised status was the cause. And while each detailed report of rabies reads like something from a horror movie — and keeps us ID docs up at night — an excellent accompanying commentary reminds us that rabies is very, very rare in the United States. Fortunately.

- Treatment with nirmatrelvir/r was associated with a lower risk of developing long COVID. Observational studies such as this one, which cannot adjust for unmeasured confounders, do not prove that treatment reduces the risk of long COVID, but they strongly suggest it — especially with the favorable results of the ensitrelvir placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial, which I have summarized previously.

- A high dose of a nonpathogenic, nontoxigenic, commensal strain of Clostridia species significantly reduced the risk of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection compared to placebo. The treatment, called VE303, came originally from healthy human stool samples, then was amplified using clonal cell banks. Though this is a small study requiring confirmation, these data plus those from the SER-109 trial strongly suggest that microbiome-based treatment will one day be part of C. difficile treatment and prevention strategies.

- Can fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) be a viable treatment for patients who suffer from recurrent multidrug-resistant urinary tract infections (UTIs)? This is a tiny (n=5) but promising case series, showing reduced frequency of UTIs and decreased hospitalizations after FMT. Every ID doctor knows just how common multidrug-resistant UTIs are today, with much attendant misery.

- The “adjuvanted” HBV vaccine (Heplisav) induced protective antibody responses in 100% of vaccine-naive people with HIV (PWH). Importantly, the usual response to this vaccine among adult PWH is suboptimal (20-70%), so these are remarkably good results. A study with this vaccine in PWH who don’t respond to hepatitis B vaccine is ongoing.

- Candida auris is spreading — fast. A particularly worrisome observation from this CDC surveillance study is that echinocandin resistance was 3 times higher in 2021 than in the previous two years. Yikes.

- An outbreak of blastomycosis in a Michigan paper plant has sickened nearly 100 people. One person has died. This is the first non-lab occupational outbreak of this endemic fungal infection I can recall, and it is still undergoing investigation.

- A physician-patient described the experience of being sent home on IV oxacillin. The clinicians treating her chose this strategy despite her protests (she preferred an oral option) and, not surprisingly, the experience was not a good one. This account should be required reading for all who do hospital-only patient care to understand just how dismal the “OPAT” — outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy — experience can be.

- Should masks still be required in all healthcare settings at all times? It’s a nuanced pro and con look at universal masking in hospitals and clinics, ultimately concluding that the time for this strategy has passed. The authors are infection preventionists, many of whom I know well (disclosure). Certainly, there are strong opinions on this matter on both sides of the debate — here’s an alternative view.

- Universal testing of admitted patients for COVID-19 may have unintended negative consequences. In this prospective study of 2,794 admissions, 129 (4.6%) tested positive by PCR, and 54 (41.9%) were asymptomatic. From this group, 39 had a cycle threshold of >35 and were deemed noninfectious. Nonetheless, 23 had adverse consequences, such as delayed medical care, canceled surgeries, or inappropriate treatment. The flip side, of course, is that universal testing also may prevent in-hospital transmissions. We’re clearly in a transition phase in healthcare for both universal masking and testing!

- Differential time to positive blood cultures acts as a helpful diagnostic tool in diagnosing central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs). In this systematic review of over 20 studies, if the blood culture from the central line turned positive 2 hours faster than the peripheral blood culture, CLABSI was highly likely. An important caveat is that this didn’t do very well for Staph aureus or Candida spp., but we generally recommend line removal for these pathogens anyway.

- Antibiotic exposure is associated with an increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease. As noted by my colleague Dr. Sanjat Kanjilal, who alerted me to this paper, this large, population-based study shows that antibiotics have way more “off target” effects than just resistance, C. diff., and side effects.

Hey baseball fans — how are you liking the pitch clock? I’m loving it!

Landon Knack throwing an entire half inning vs. Pedro Báez throwing 1 pitch. pic.twitter.com/wHa2p6K7k8

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) February 27, 2023

April 8th, 2023

Travel Clinics and a Travel History to Beat All Travel Histories

Dear All,

Dear All,

I’ve received some very helpful and quite critical comments about the original post that was here. Having re-read the original, I’m acknowledging my mistake and want to apologize to my colleagues, many of whom do travel medicine with true expertise, excellent intentions, and for the benefit of travelers everywhere. My bad for not emphasizing this fact in the first part of the post.

Awaiting input from my editors, I temporarily removed it yesterday, but now have replaced it below. There are some edits to parts that I especially regret, but the essence is there.

Thanks everyone for reading, and helping me keep this a useful, supportive, and I hope educational place.

Paul

Confession: I have mixed feelings about travel clinics.

On the one hand, they provide a useful service to people who might be unaware of the dangers of the exotic places they plan to visit. It’s a place for sensible counseling:

Don’t eat street food! Don’t play with the stray dogs! Don’t swim in the Omo River!

Travel clinics offer a cornucopia of vaccines — yellow fever, typhoid, hepatitis A, rabies. A good travel doctor or nurse — optimally an experienced and enthusiastic traveler themselves — really knows the risk of Japanese encephalitis on your 3-week trip to Myanmar. They also have wise advice about malaria prophylaxis and other treatments to take along, just in case.

Plus, falling outside of many insurance plans and serving a generally well-to-do crowd, travel clinic is one of the few places ID doctors generate revenue in the outpatient setting. These money-makers are so few and far between for us that it’s hard to pass them up.

We have an active travel clinic, and the patients are really happy to have this convenient, one-stop service. They love it! And our travel clinic providers are great. Demand is sky-high, showing a reassuring return to pre-pandemic travel.

All good so far.

On the other hand, travel clinics sometimes cater to the worried well, offering dubious value if the destination is simply a long trip, the planned activities not so risky. Does the business traveler to Bangkok or Johannesburg, the honeymooner to Fiji, or the tennis enthusiast going to a resort outside of Buenos Aires really need to go to a travel clinic before their trips? Of course not, yet I’ve seen all of these examples come through our doors.

Additionally, the education component can paradoxically make the worried traveler feel worse. A recently retired ID doctor here in New England regularly did travel clinic at his hospital, but so hated to travel himself that he sometimes bluntly told his patients — “Look, if it were me, I wouldn’t go.” No doubt he was responsible for a high volume of canceled first-class airfares.

Last, some of the people who really need travel clinics can’t access them because, as mentioned, insurance often doesn’t cover it. This creates a two-class level of care analogous to traveling business vs. coach, but since it involves healthcare, is far more disquieting.

Travel clinics are on my mind because I recently had the distinct pleasure of reconnecting with a college friend, Mike Reiss. Professionally a comedy writer (he’s one of the original writers for The Simpsons, among other credits), Mike loves to travel.

Or more accurately, Mike’s wife Denise loves to travel, and Mike is totally smitten with Denise and will do whatever she wants.

Let me emphasize that “loves to travel” barely begins to describe their enthusiasm. They’ve now logged well over 100 countries, travel regularly to places you have not been (trust me on this one), and have had some remarkable experiences — many of which Mike details in his podcast, What Am I Doing Here?, which I highly recommend.

Mike chatted with me recently, and our conversation is incredibly funny — that’s because everything Mike talks about is incredibly funny! Listen here at the bottom of this post, or wherever you get your podcasts. You won’t want to miss it. His travel history reads like a parody of an ID certification exam question.

And Mike, here’s some friendly advice — if you don’t want to go to a travel clinic, here are the big four I’d recommend for a traveler like you, easy stuff you can get from your primary care doctor:

- Get the hepatitis A vaccine. Two shots, you’re good for a lifetime.

- Typhoid vaccine if indicated — either the shot or the pills.

- Take some azithromycin with you in case of severe traveler’s diarrhea.

- If you’re going to a malaria hotspot, take malaria prophylaxis.

Even better, check out the CDC’s travel web site. I use it all the time.

March 27th, 2023

Three Effective Treatments for COVID-19 Not in Treatment Guidelines — at Least Not Yet

A few weeks ago, in a patented (and copyrighted and trademarked) Really Rapid Review™, I summarized some of the Greatest Hits from CROI 2023. The conference included new data on not just HIV, but also a grab bag of opportunistic infections, STIs, viral hepatitis — and, as has been the case since 2020, COVID-19.

A few weeks ago, in a patented (and copyrighted and trademarked) Really Rapid Review™, I summarized some of the Greatest Hits from CROI 2023. The conference included new data on not just HIV, but also a grab bag of opportunistic infections, STIs, viral hepatitis — and, as has been the case since 2020, COVID-19.

You know, right in the wheelhouse of readers like you.

At least most of you. Wrote one longtime fan after that post:

Paul,

That was undoubtedly the most boring blog post you’ve ever done.

Mom

Um, certainly no one ever accused my mother of hiding her true feelings!

Risking again putting this very same reader to sleep, I bring you now more data presented at CROI — three studies highlighting promising outpatient COVID-19 treatments. The full presentations are now available on the CROI website, and I’ve linked them below:

1. Ensitrelvir. A SAR-CoV-2 protease inhibitor like nirmatrelvir, ensitrelvir at two doses was compared to placebo in a randomized trial done in people at low risk for severe outcomes — meaning younger (12–69 years old), mostly vaccinated, and lacking risk factors for severe disease.

Ensitrelvir shortened the duration of symptoms by about a day (the primary endpoint) and hastened the time to the first negative SARS-CoV-2 viral test. Perhaps most importantly for this group at low risk for hospitalization but still vulnerable to long COVID, a questionnaire targeting symptoms of long COVID conducted at 3 and 6 months showed a significant reduction in the treatment group compared to placebo. The protective effect was greater in those with more severe disease at start, the people at greatest risk of getting this complication to begin with.

Based on these results, I think these are the strongest data we have that antiviral therapy reduces the likelihood of developing long COVID. Yay to that. Note that ensitrelvir already has approval for treatment of COVID-19 in Japan.

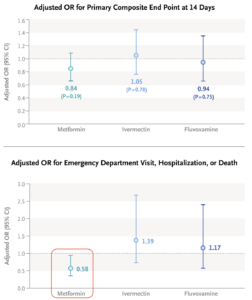

2. Metformin. In the quest for “repurposed” drugs for COVID-19, the hits (dexamethasone, tocilizumab, baricitinib) lose badly to the misses (lopinavir/ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin, azithromycin, colchicine, fluvoxamine, numerous others), especially for outpatient treatment. Could metformin be the exception?

At CROI, the investigators of the COVID-OUT study presented data on their randomized clinical trial of metformin versus placebo. Treatment was significantly better in a composite outcome of emergency department visits, hospitalizations, or death; the drug also demonstrated a significant antiviral effect. Furthermore, long-term follow-up found that treated patients were less likely to receive a diagnosis of long COVID by their providers.

Add to these benefits the widespread familiarity that clinicians have with this drug, its well-established safety profile, and its extraordinarily low cost, and we might have a winner here, folks.

3. Pegylated interferon lambda. Need I say more?

I won’t pretend there aren’t issues with these three studies. Here are a few worth exploring:

Ensitrelvir: The study evaluated two doses of the drug, 125 mg and 250 mg once daily; the lower dose appeared to be more effective, for unclear reasons. Plus, the long COVID endpoint analysis I highlighted was not protocol-specified, and hence must be considered exploratory.

Ensitrelvir: The study evaluated two doses of the drug, 125 mg and 250 mg once daily; the lower dose appeared to be more effective, for unclear reasons. Plus, the long COVID endpoint analysis I highlighted was not protocol-specified, and hence must be considered exploratory.- Metformin: The primary endpoint of the metformin COVID-OUT study, which included home oxygenation results as part of a composite clinical endpoint, was negative. Subsequently, the investigators learned that the home oxygenation results were unreliable, which undoubtedly introduced a lot of noise into analysis of this endpoint. Note that the positive secondary endpoint for metformin (emergency room visits, hospitalization, or death) did make it onto the Research Summary (see figure — edit mine), but it’s not the message most take from the published paper.

- Pegylated interferon lambda: The TOGETHER trial enrolled patients in Brazil (mostly) and Canada; this study previously yielded favorable results with fluvoxamine. Given the subsequent negative results with fluvoxamine, should we be skeptical of any data coming from this study?

Still, there’s a lot to like here with all three treatments, especially given our limited current options now that monoclonal antibodies are gone. And importantly, the three outpatient therapies — Paxlovid, molnupiravir, intravenous remdesivir — have their own issues, some of which I’ve summarized previously.

Some might think we’re done with COVID-19, so why invest in studying further treatments? To those people, let’s face facts — this respiratory virus isn’t going anywhere, still accounts for hundreds of deaths a week in medically vulnerable populations, and causes enormous disruption in workplaces and schools. An annual bump in cases each respiratory virus season is all but a certainty given what we’ve seen the past three winters.

If you’re interested in hearing more details about these novel treatments, how they might compare to what we currently have, and how they could be investigated further, listen to the discussion I had with University of Minnesota’s Dr. David Boulware on an IDSA podcast, just released. He truly deserves the label “clinical trialist extraordinaire,” which is how I introduce him.

It’s available on the IDSA site along with a transcript, or wherever you get your podcasts, or right at the bottom of this post.

Hey Mom — am sure you’ll love it!