An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

October 17th, 2023

A Brilliant Strategy for Conducting Clinical Trials — The ACORN Study

Prompt: Make a cartoon battle between cefepime and pip-tazo.

The secret to doing a great clinical trial is quite simple. Here, I’ll share it with you:

- Come up with an important clinical question for which there’s true equipoise.

- Choose primary and secondary endpoints that people care about.

- Make the inclusion and exclusion criteria easy to understand and chosen so that they define a readily available and broadly applicable study population.

- Create a system in which referrals, enrollment, and informed consent are as frictionless as possible.

- Start the study, and collect the baseline and follow-up data.

- Analyze and report the results.

There, piece of cake! Off you go, time to get started.

I hope your sarcasm meter is turned on because pulling off any of the above is in fact exceedingly difficult. That’s why the ACORN study comparing cefepime with piperacillin-tazobactam (pip-tazo) — presented last week at IDWeek, and simultaneously published in JAMA — is so wonderful. And it’s not just because of its clever name: Effect of Antibiotic Choice On ReNal Outcomes.

Let’s go through the above recipe and see how they did.

Come up with an important clinical question for which there’s true equipoise. In adults hospitalized with acute infection, which antibiotic is better: cefepime or pip-tazo? Members of Team Cefepime would cite pip-tazo’s notorious association with kidney injury, especially when combined with vancomycin, and the broad anaerobe coverage, which may further disturb the microbiome.

Team Pip-Tazo would counter by reminding Team Cefepime about their drug’s neurotoxicity and say that pip-tazo’s nephrotoxicity may be artifactual — the result of inhibiting tubular secretion of creatinine, with no change in actual glomerular filtration rate (GFR) based on cystatin C measurements. Plus, Team Pip-Tazo will defend that extra anaerobic (and enterococcal) coverage as helpful for empiric therapy.

(Brief shout-out to Team Neither, made up of antibiotic stewards arguing that empiric coverage of Pseudomonas is not needed for all acutely ill people. You’re welcome.)

Choose primary and secondary endpoints that people care about. From the paper’s quick summary:

Does the choice between cefepime and piperacillin-tazobactam affect the risks of acute kidney injury or neurological dysfunction in adults hospitalized with acute infection?

That’s pretty clear. After all, the broad-spectrum coverage of these two drugs is similar, so adverse events are likely to dictate the best choice. If the study finds differences in efficacy, that would be quite interesting as secondary or exploratory endpoints. But common sense dictates that they’re probably not that different in efficacy, so setting the study up as a superiority trial on efficacy (“powering” for an endpoint of days of ICU care or death) would require a sample size so large as to make the study impractical.

Make the inclusion and exclusion criteria easy to understand, and chosen so that they define a readily available and broadly applicable study population. How about anyone in the emergency room or medical ICU for whom a clinician plans to start one of these two antibiotics? That’s pretty simple — and it must happen a zillion times a day in hospitals all over the world.

Create a system in which referrals, enrollment, and informed consent are as frictionless as possible. Here’s the true genius of the ACORN trial. After the doctor ordered either cefepime or pip-tazo in their medical center, the investigators leveraged the electronic medical record to screen automatically for critical exclusion criteria. With none found, their order triggered a prompt for the doctor to consider enrolling the patient in the trial.

During primary investigator Dr. Edward Qian’s excellent presentation at IDWeek, his slide with the image of the prompt (available on the study’s supplemental appendix) elicited gasps of amazement — at least it did from clinical trials geeks like me. This is just a brilliant way to encourage referral and enrollment. Frictionless clinical research at its best!

(Brief aside: I’m not sure about your hospital, but where I work, changes to EPIC, our electronic medical record, move forward about as fast as that slug you found under your garden’s flowerpot. What was this wizardry Dr. Qian and colleagues did to scoot this slug along?)

But what about informed consent? As discussed in detail on page 10 of the study’s appendix, it turns out informed consent to a study can be waived if a study is deemed minimal risk and the intervention is an emergency. Empiric cefepime or pip-tazo for acutely ill, hospitalized febrile adults certainly meets the criteria of standard of care (minimal risk), and the sooner antibiotics start the better (emergency). Check and check!

Start the study, and collect the baseline and follow-up data. From November 10, 2021 to October 7, 2022, 2634 participants enrolled in the study at a single center. (I told you this happens a zillion times a day — full enrollment in less than a year from just one hospital!) Patients enrolled were well-matched at baseline, with sepsis the initial diagnosis in just over half. The median duration of the initially assigned antibiotic was 3 days, but a substantial fraction received treatment for longer.

Clinicians added vancomycin in 83% of the cefepime group and 81% of the piperacillin-tazobactam group for a median of 2 days. Roughly equal proportions of both study arms had treatment modified via other antibiotic changes, including switching to the other drug (cefepime to pip-tazo in 19%, pip-tazo to cefepime in 17%), or broadening treatment by adding an aminoglycoside or switching to a carbapenem. In other words, the very common practice of antibiotic switches for critically ill patients — don’t just stand there, start meropenem! — was equally common in both arms.

Analyze and report the final results. For the primary endpoint, the highest stage of acute kidney injury or death by day 14 did not significantly differ between the cefepime group and the pip-tazo group. Even the addition of vancomycin didn’t have a differential effect. However, for the important secondary endpoint of delirium or coma, here the pip-tazo group had significantly fewer hospital days with this complication. Deaths were similar between arms, as were a bunch of other clinical and laboratory endpoints.

So Team Pip-Tazo wins, though it’s a really close call. And may the pip-tazo/vancomycin nephrotoxicity RIP, at least based on this short-term exposure.

Now no study is perfect, and the authors responsibly address the limitations in their discussion. For me, the biggest one is that as an open-label study, clinicians may have been more prone to make the diagnosis of encephalopathy with cefepime, and this turned out to be the only significant difference between the two strategies. Read the full paper and the accompanying editorial to see further discussion.

Limitations notwithstanding, the study remains an impressive feat of generating clinically relevant evidence on an important topic, and doing so quickly in a way that harmonizes with actual patient care. The novel strategy of enrolling eligible participants through the electronic medical record in such a seamless way is a model for other clinical questions in both ID and beyond.

What should we study next?

Because it can’t be as hard as doing these things on a treadmill …

October 8th, 2023

An October ID (and Non-ID) Link-o-Rama

The Lyme Laser.

For those venturing next week to IDWeek here in Boston, fall gives us our very best weather. Comfortable sunny days with brilliant blue skies, cool evenings, low humidity — great weather for exercising and sleeping. Usually you just need a light jacket. And now, after one of the rainiest Septembers on record (boo!), October has so far has been heavenly (yay!).

But you don’t come to this site for a New England weather report, which might change day-by-day anyway.

Let’s go to the links, starting with ID topics:

- Lyme vaccine clinical trials continue, and one candidate is quite far along. Fingers crossed, at least one of these two vaccines will be safe and effective, then widely adopted in highly endemic areas. My non-medical friends here frequently wonder why there is no vaccine for humans if their dogs can get one. I tell them there was one — but it got caught up in the controversial cloud that follows this disease around like dust over Pigpen.

- How’s this for an example of this dust? Or crap, to be more accurate: You can get treatment with a “Lyme Laser”. It “addresses the concern of the biofilm established in the advanced stages of Lyme disease,” and “enhances the body’s natural abilities to improve function and regeneration.” Seriously, the unvalidated and potentially dangerous “treatments” offered for this serious infection continue to strain imagination. Note that pricing on this site (and others just like it) is conspicuously absent.

- The NIH-sponsored clinical trial ACTIV6 for COVID-19 is still open, evaluating metformin. The study will (I hope) confirm the benefits seen in the COVID-OUT trial, in which metformin reduced the incidence of long COVID by 41%. Importantly, people can also take other COVID-19 treatments and still participate. I’m particularly interested to see if it can reduce the incidence of rebound after nirmatrelvir/r, which remains a bedeviling problem.

- PEPFAR may be in trouble. Could a rare example of bipartisan political support for a hugely successful public health program come to an end? That’s the worrisome message expressed in recent coverage of PEPFAR, which pays for HIV treatment in resource-constrained countries with high HIV prevalence, especially in Africa. At last estimates, the program has saved 25 million lives. Wow.

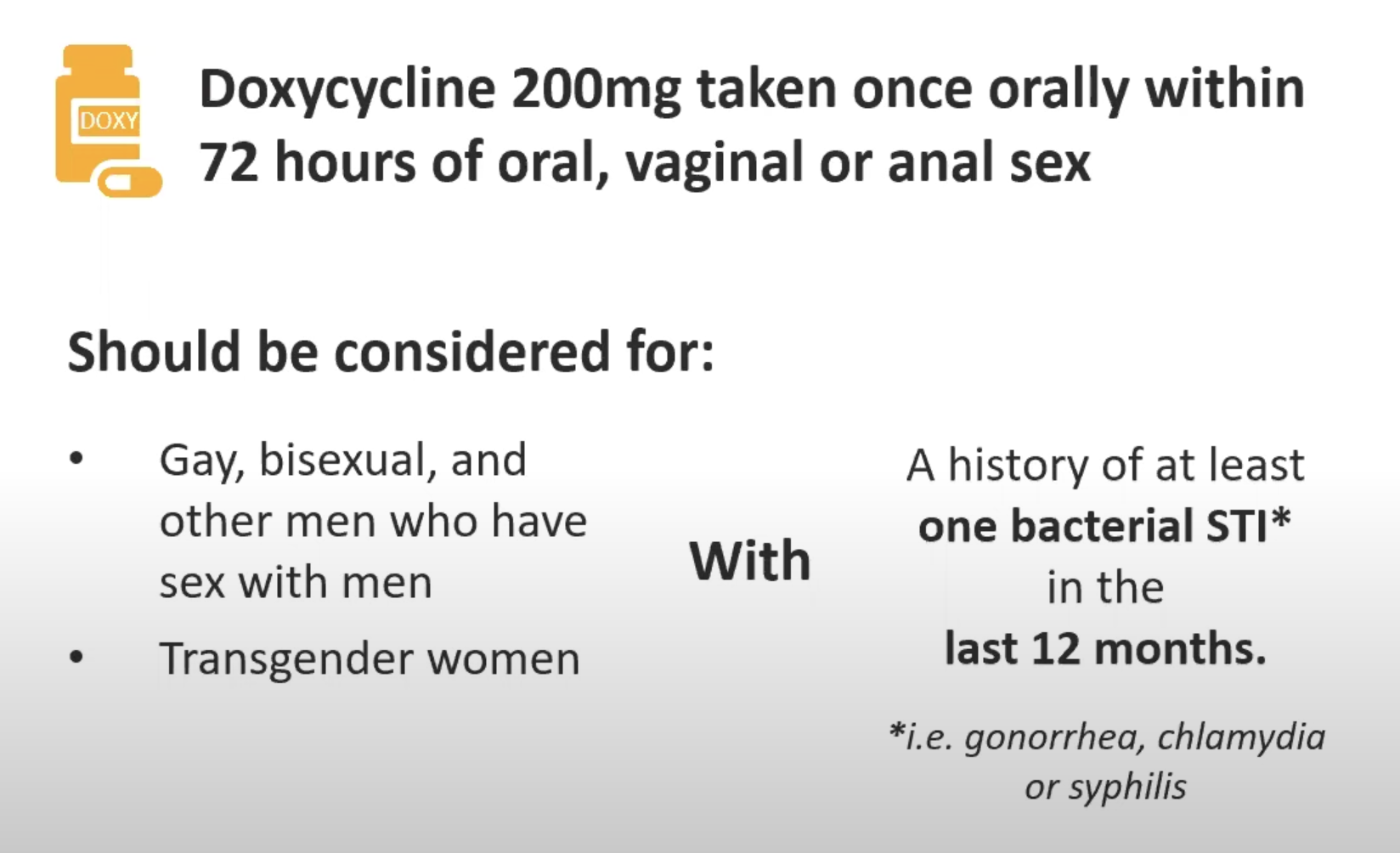

- The CDC called for comments on the use of doxycycline for post-exposure prophylaxis for STI prevention. You will not find them by clicking this link, and getting to them is tricky, so here are “guidelines” on how to find the draft guidelines: Go this YouTube video, watch the summary of the evidence, and eventually (at 15:15) you’ll reach this:

- In related news, this modeling study shows that adopting doxycycline for STI PEP using these criteria would be an efficient use of resources. Monitoring for STI resistance will be critical.

- Can oral swabs run on a multiplex PCR platform help diagnose community acquired pneumonia? In this study, correlation between oral and lower respiratory results was high when S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae were the cause of the pneumonia. Sure would be easier than trying to get an induced sputum.

- Ceftobiprole was noninferior to daptomycin in treatment of Staph aureus bacteremia. Wow, talk about a blast from the past — I thought this cephalosporin (with activity against MRSA) had long been abandoned, but here it is again! Look for this paper in many ID and medicine journal clubs over the next few months, as there are numerous questions about the study design and the clinical implications. I worry in particular about the control arm — daptomycin (not oxacillin or cefazolin) for MSSA (76% of study participants)? And was daptomycin underdosed?

- In other MSSA bacteremia research, here’s a different prospective randomized clinical trial: The study compared cloxacillin alone vs. cloxacillin plus fosfomycin. The combination regimen failed to show superiority, despite more rapid clearance of bacteremia at day 3 — reminds me of adjunctive gentamicin in this regard. Great to see these studies of Staph aureus bacteremia, which is almost certainly the most common reason for inpatient ID consults, at least in the United States.

- Herpes simplex encephalitis has a high rate of subsequent neurologic complications, with immune-mediated choreoathetosis particularly common. This in-depth study suggests corticosteroid treatment of this late complication is warranted. And it’s a reminder that despite being “treatable” with high dose intravenous acyclovir, HSV encephalitis remains a devastating diagnosis — patients and their families should be counseled up front about the potentially serious outcomes.

- The viral dynamics of COVID-19 have dramatically changed in relation to symptom onset since the start of the pandemic. Viral loads of SARS-CoV-2 now peak at day 4 of symptoms (not at or right before symptoms start), with rapid antigen testing gradually increasing in sensitivity over symptom-days 1-4. The results clearly emphasize the need to re-test in patients with negative tests early in the illness, and also have infection control implications. Our broad pre-existing immunity is responsible for this “new normal”.

- The WHO endorsed use of a highly effective malaria vaccine, the second vaccine now available. Work on malaria vaccines has been a struggle for decades, so this progress is a welcome advance indeed — because in separate news, the mosquitoes appear to be winning. Global malaria deaths are ticking up, and other mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue and chikungunya continue to spread.

- These authors provide an interesting perspective on those annoying low-level viral load results that create all kinds of anxiety — namely, that the labs and clinicians should focus on the 200 copies/mL threshold as the important one for “U=U,” as this was the lowest threshold used in the large studies evaluating HIV viral load and transmission. While I agree that this is a reasonable approach (and the one I use in clinic), there is some uncertainty around this threshold, since most of the people in these studies of transmission on ART had undetectable viral loads — the 50-200 sample was necessarily small. Nonetheless, I 100% agree that flagging these results with a big red exclamation point is unnecessary. And check out panel 4 in the figure.

- The Nobel Prize in Medicine went to Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman, whose work led to the development of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19. Lots of chatter about how Karikó “failed” in traditional academic research, which prompted her to leave her university lab setting because she was unable to get grant support. Let’s face it, the weeding out process in academic medicine specifically and science in general will definitely overlook some innovative geniuses, as grant-review committees are famously conservative in favor of established researchers and familiar strategies.

- You know that strange sensation of time distortion since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic? “Pandemic skip” is a great descriptive term. And though the writer of this piece is just 30, it applies to every age, doesn’t it? And sometimes it feels like just a few months since those terrible dark days in 2020, and at other times it feels like it must have been many, MANY years ago, certainly much more than just 3. Don’t you agree?

- Here’s a poetic rumination on microbial odors. Impressive alliteration on display: “From the fungal fragrances that sing of environmental mold to the bacterial bouquet that warns us off week-old leftovers, our air comprises a microbial miasma of information, ripe for research and exploration.” I’m sure Cliff, the C. diff-sniffing dog, would agree!

Now, a brief non-ID section:

- Over in The New England Journal of Medicine (the Mother Ship of this Journal Watch enterprise), the editors kindly published how I felt when the news broke about a business decision that will dramatically reshape the clinical, research, and training experience in Boston — the departure of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where I work. Still can’t believe this is happening. Makes me very sad.

- These two oncologists provide a highly critical viewpoint on Maintenance of Certification by the American Board of Internal Medicine. Interesting to contrast their approach with my more ruminative account, but both ultimately come to a similar conclusion, which is that there must be something better.

- Here’s a wonderful essay for those of us of a certain age, contrasting the experience of travel both with, and without, illness. On the topic of the ailments that start accumulating as you age: “It’s as if we were all devices made by some big tech company, designed to start falling apart the instant the warranty expires and to be ingeniously difficult to repair, with zero support for older models.” Wow, wish I’d written that sentence.

- You can now order medical care on Amazon. My wife, a primary care pediatrician, says that everyone knows this by now, but somehow I missed it. But look — plenty of infections on the list! UTI, HSV, vaginal yeast infections, sinusitis. Text- or video-visit based care. And if your diagnosis is COVID-19, it’s $35 for text care, $75 for a video. Stuff like this makes you wonder about this future of healthcare, for better and (mostly) for worse, doesn’t it?

- You don’t have to be a baseball fan to find this documentary of Yogi Berra joyful and fun. Berra seemed to be the kind of person everyone loved — such a desirable trait! That he happened to be a world-class athlete (and kind of unusual looking, with quotable quotes) added to the charm. I’m sure that his very charismatic granddaughter, Lindsay, will no doubt wonder what she and her famous grandfather are doing on an ID blog.

Since people will be coming from all over the world to IDWeek, how about this impressive and nimble take on country-specific accents? Wow, what talent. What’s your favorite?

Hope to see many of you at IDWeek!

September 22nd, 2023

Long-Acting Cabotegravir-Rilpivirine for People Not Taking Oral Therapy — Time to Modify Treatment Guidelines?

Cephalopods, by Jean Baptiste Vérany.

HIV treatment guidelines are understandably reluctant to endorse practices that have limited data. Having served on two such panels (previously, DHHS and currently, the IAS-USA guidelines), I totally get this — you don’t want to put a stamp of approval on strategies that may ultimately do more harm than good.

With the caveat that I cannot speak for the guidelines panel I currently serve on, I can give you my opinion on a topic much discussed among us ID and HIV specialists — namely, the use of long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine in people not taking standard oral ART, despite all our efforts to encourage them to do so.

Here it is:

If the alternative is untreated and progressive HIV disease, and the patient has advanced immunosuppression, we should stop discouraging use of this potentially life-saving therapy.

I base this on what are now a few published studies, including the original reports from UCSF, a follow-up from them with a larger sample size, a modeling analysis demonstrating substantial projected survival benefits, and now — just published in Clinical Infectious Diseases — a small case series from a different clinic with comparably excellent outcomes.

At a Ryan White-funded HIV clinic at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, clinicians began offering injectable CAB/RPV in February 2022 as a salvage option to people with HIV (PWH) who had viremia despite intensive case management strategies. Since that time, they have offered it to 12 patients — 7 women, 5 men. The baseline mean CD4-cell count was 233, and HIV viral load 152,657 copies/mL, with 5 of 12 having a history of AIDS-defining opportunistic infections.

With the caveat that follow-up is necessarily short, the results were excellent: All 12 achieved viral suppression within 3 months of treatment initiation, with no virologic rebound to date. They also reported good immunologic responses and high adherence to scheduled injections. These favorable results are all the more remarkable since some of the participants had NNRTI and INSTI resistance mutations, though none had full predicted resistance to either drug.

The experience with these dozen patients is now being reproduced anecdotally in small case numbers from other centers, including our own. While San Francisco led the way, this is doable in any HIV treatment clinic with intensive case management services.

Meanwhile, the DHHS HIV treatment guidelines continue to state the following:

The long-acting ARV combination of injectable cabotegravir (CAB) and RPV is not currently recommended for people with virologic failure [DHHS].

I strongly believe the time has come for us to revise these prohibitory statements (a similar one appears in the IAS-USA guidelines). Such statements may make it difficult for clinicians to procure this treatment for PWH whose treatment options (oral ART) otherwise just aren’t working. One can craft language with appropriate cautionary statements describing the unusual settings in which CAB-RPV is the best — and, importantly, the only — option for people with virologic failure.

Here’s a go at this:

Under rare circumstances, long-acting CAB-RPV can be an option for people with virologic failure when no other treatment options are available or effective. Such treatment must be accompanied by intensive case management and close follow-up. It should be limited to PWH who meet the following criteria:

- Unable to or cannot take oral ART

- Are at high risk of HIV disease progression (CD4 < 200 or a prior history of AIDS-defining complications)

- Have virus susceptible to both CAB and RPV

- Can be supported by intensive case management services

Sure, there will be cases where treatment failure with resistance occurs; where patients are lost to follow-up; where we will need to battle with payers to convince them to cover this non-FDA–approved indication; where the team of people (and it’s always a team) charged with case-management and medication administration spend enormous time and energy to no avail.

I acknowledge these issues and frustrations, but at the same time, ask — what is the alternative?

It can’t be to withhold the only regimen that might help them. Because as shown in the figure posted below, the median life expectancy for someone with AIDS in the pre-ART era — advanced HIV disease, no treatment — was less than 2 years.

When I was a medical resident and ID fellow, the median survival for a person diagnosed with an AIDS-related opportunistic infection was around 18 months pic.twitter.com/yXe37iDFgS

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) August 27, 2023

I think we’d all agree that this grim prognosis is simply unacceptable if we have an available effective treatment we’re not using.

September 8th, 2023

Endless Recertification in Medicine — Some Thoughts About the Tests We Take

William Heath, March of Intellect, 1829.

The tests issued by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) for credentialing physicians are much in the news again. There’s even a petition circulating to eliminate the Maintenance of Certification (MOC) process entirely, signed by nearly 20,000 physicians.

I have a bunch of memories, thoughts, and feelings about ABIM and the tests they issue. They’re all jumbled around in my head in a formless blob.

So formless, in fact, that I struggled to put them into a well-structured post. So here they are, in 6 chapters, presented in roughly chronological order.

Chapter 1: The Early Days

I remember a meeting we had during my medical residency where someone from ABIM came to our program to announce the end of “lifetime certification,” starting with our year of residency. (I think he was from ABIM … it was a person not on our faculty.) We were the very first year with a new requirement, thank you very much.

No longer would people who passed their Internal Medicine or subspecialty boards be “grandfathered in” for eternity. At 10-year intervals, repeat examinations would be necessary — length, type, cost to be determined.

(Origin of the term “grandfathered” — in case you were wondering.)

The new program was called “Maintenance of Certification,” or MOC, and would provide hospitals and insurance companies a different benchmark for credentialing physicians. You signed up for MOC by sending in a sizable payment, and then the ABIM site would list you as participating in the program. ABIM promised to send you reminders when your 10-year period was about to expire.

As we heard it, it was a decision passed down from above, one with authority that we assumed had strong data behind the policy. We had no way of pushing back or protesting.

No one opposed some sort of process of continual learning for physicians — but wasn’t that the purpose of good Continuing Medical Education (CME)? And it seemed especially ironic that only the older docs got a lifetime pass. We were miffed, but powerless.

The MOC process was widely adopted, and it became a standard part of employer checklists for hiring and retaining medical staff, and insurance companies for keeping or dropping you from their ranks. If Dr. Hugo Z. Hackenbush only passed his original exam, but failed to sign up for the repeat exams, he risked losing his job. Or not getting paid.

Quite the motivation to participate!

Chapter 2: The Middle Years — Criticism, More Requirements, and a Retrenchment

Widespread adoption notwithstanding, the ABIM and its requirements have long had their share of critics. A Newsweek article in 2015 was particularly vicious. More recently, cardiologist Dr. Westby Fisher has tirelessly laid out his arguments for elimination of the MOC requirement (arguments here and here).

Numerous other editorials and position papers have appeared over the years, too numerous to cite, with the message that ABIM has no good data that their process improves physician quality; that the tests are not clinically relevant; that it’s too expensive; that all it does is enrich an already financially thriving not-for-profit organization; and that it fuels clinician burnout.

The apotheosis of these criticisms came when ABIM added layers of other requirements to the MOC process beyond the recertification exams. Remember these “Practice Assessment, Patient Voice and Patient Safety” programs? Yeesh.

We all spent hours completing “quality improvement” projects of dubious (and sometime frankly bogus) worth, just to say we’d done it. Where did all these forms go once we submitted them? Was quality ever improved by these tasks? (Doubtful.) Who reviewed them?

As for “Practice Assessment,” I memorably asked a colleague of mine, a terrific clinical pulmonologist, to complete one of the ABIM mandated surveys on my behalf. He was supposed to call a toll-free number and answer a series of templated questions about the quality of care he’d observed me give to our mutual patients. He kindly agreed to do it.

Or so I thought — he later told me he never got around to it. But ABIM still said I passed his individual “Practice Assessment” standard. Maybe he sent them his response by telepathy?

Under a torrent of criticism, these extra requirements ended in 2015 with a mea culpa from the ABIM leadership. Good move on their part, as it was the very essence of overreaching by a powerful organization. But the recertification process (MOC) remains, as do the criticisms.

In short, complaining about ABIM, and the MOC in particular, offers a rare example of doctors coming together in a remarkable cross-specialty consensus. Accurate quote from Dr. John Mandrolla:

[ABIM] has done what seemed impossible: got docs of all political leanings to agree on one thing —> ending MOC.

Chapter 3: Taking the ABIM Exams

Through volume alone, I’m something of an expert on taking ABIM exams. I have ID specialty training along with Internal Medicine certification, so I’ve now taken the Internal Medicine boards 3 times, and the Infectious Diseases boards 4 times. Lucky 7!

I’ve spent thousands of dollars for the examinations, sitting for a whole day (a work day) in a high-security environment that treats all us test-takers like potential drug smugglers or terrorists. You check in at a test center, surrender all your possessions and place them in high school-style lockers, take the locker key with you, and head to the testing rooms.

These rooms are gloomy, windowless, and airless places, watched over by suspicious test proctors behind one-way mirrors. The rooms are filled with side-by-side desk cubicles. Each desk has a monitor, keyboard, and mouse.

(Computer mouse, not the squeaky rodent with whiskers. All living things would leave this hostile environment as fast as possible, and that includes vermin.)

The testing day has tight restrictions on bathroom breaks and lunch. You can’t ask anyone for help with anything related to test content. (What happened to medicine as a “team sport”?) You have one source of information — UpToDate. You keep feeling as if you’re about to infringe on some unspoken security policy, and end up being reported to the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), putting you immediately on a “no fly” list.

And here’s another thing about those thousands of dollars we pay for the privilege of taking the test — when you finish residency, nobody tells you who’s responsible for the payments. While some have it as a job benefit, most doctors must pay out of pocket, with time away from productive patient care — leading to additional lost revenue for those in private practice or paid by clinical RVUs. If you take a board review course, that’s an additional hefty sum.

In summary, taking the test is no one’s idea of a fun day at work, and the cost of ABIM MOC isn’t trivial — these rankle pretty much everyone I know.

Chapter 4: A View from Inside (Sort Of)

Full disclosure time — for several years, I was on the committee that wrote the questions for the ID boards.

(Ducks.)

I’d meet with ID colleagues twice yearly with diverse areas of expertise, and we’d test our questions against each other with the guidance of an ABIM official. These were incredibly educational meetings, and I learned a ton from my smart colleagues — arguably more than I’d learned preparing for or taking the boards themselves.

We tried to make the test questions as clinically relevant as possible, of course. Part of our job was to weed out those we thought tested pure memorization, or “look ups,” or highlighted outdated diagnostics or therapies. Each question was carefully reviewed so that there was a clear question, and an unambiguous single-best correct answer, at least so we thought.

But — and this is really important — no matter how good the question, we had no idea whether these test questions evaluated the clinical competency of a physician. This was always a big reach.

Two major barriers: First, not everyone in ID has the same spectrum of practice. Even within our little specialty, there are some who focus on transplant ID, and others who rarely if ever see these patients; some do lots of longitudinal HIV care, and others do none; some are deeply involved in infection control, while others barely touch the topic. I could go on and on, but these differences were obvious barriers to writing clinically relevant questions with broad applicability.

And I am 100% sure this issue applies to every medical specialty. Example — Dr. Mikkael Sekeres, who specializes in hematologic malignancies, describes what it’s like taking the MOC exam in Hematology-Oncology:

… over 90% of the questions have nothing to do with the patients I actually see in my specialty practice, and haven’t seen in over 2 decades of practice.

The second problem was the test process itself. To be blunt, nobody practices medicine in the style of the proctored exam — high stress, limited information resources, time-limited, non-collaborative. No testing of the importance of patient communication, eliciting preferences in ambiguous situations, accounting for differences in medical literacy, or the ability to seek out help from other clinicians. In a world of increasingly sophisticated emulations, the ABIM monitored test setting is the polar opposite of practice, and multiple choice question are an overly simplified probe of the complexities of clinical reasoning.

So what is being tested, really, with the ABIM exams? I learned that they’re evaluating the ability of candidates to answer test questions vetted by psychometricians as being “discriminating” — answered correctly by high-performing candidates and incorrectly by low-performing test-takers. These are the best questions, per ABIM standards.

It’s a form of circular reasoning that somehow is supposed to correlate with the ability to care for patients seen in the office or hospital setting. In other words, even our best, most clinically relevant questions sometimes got tossed out as being not discriminating enough — too easy or too hard based on this self-reflecting metric.

If you’re shaking your head right now, I don’t blame you.

Chapter 5: The Latest Innovation — Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment

Astute readers will note that I’ve “only” taken the Internal Medicine boards 3 times. It’s not because I’ve let that certification lapse — it’s because ABIM now offers a new way to maintain board status, and that’s by taking unproctored exams at home, called the “Longitudinal Knowledge Assessment,” or LKA.

Send in your payment, and 30 questions arrive quarterly, giving brief clinical vignettes, a question, and then multiple choice answers. Notably absent from the answer choices is “I would never manage a case like this on my own, I’d ask or refer to a colleague.”

Tough luck. You have 4 minutes to answer each one, and can use any resource.

Whether this LKA process more accurately correlates with clinical competency than the proctored high-security test is anyone’s guess. Four minutes to answer a clinical question? How did they come up with that? Does research show that 4 minutes is some magical threshold that skilled physicians find sufficient for every clinical question? Do the doctors needing 5 minutes need some sort of remedial training in how to look things up more efficiently?

Plus, I have no idea what the criteria are for success in this home testing program. I’m just answering the questions, hoping I’m getting enough questions right to maintain my certification status. La de da.

Certainly this LKA feels less punitive than the proctored exam at the dreaded test center. But there’s a negative trade-off, and it’s not trivial. These questions arrive on a regular basis, an endless 3-month cycle that stretches on indefinitely. It feels like a coach told you to start running laps for fitness but declined to tell you how many.

Big picture — do I really need to do this the rest of my career? I’m only a year or so into it, and confess it feels about as rewarding as renewing your car’s registration or paying your monthly utility bills.

And let the record show that the much-hyped flexibility of the LKA led to one of the most tone-deaf examples of organizational publicity in the history of academic medicine — a doctor posted, on the ABIM site, an account of her doing exam questions while “on the adventure of a lifetime, visiting all the lower 48 States in an RV.”

I’m sure she meant well. But the response from the medical community at the implication that we spend our vacation time doing MOC was predictable outrage.

Never forget!

Your MOC fees paid someone at ABIM to come up with this ad!END MOC sign the petitionhttps://t.co/OYfhsxZkkG pic.twitter.com/MzPI9Ct9Lv

— Aaron Goodman – “Papa Heme” (@AaronGoodman33) August 2, 2023

And while ABIM deleted the original tweet promoting the post (but not the post itself), and apologized for it, some of the responses were very, very funny indeed. Here’s my favorite:

Getting married this weekend and want to get a head start on Q3 LKA questions? Hear from Dr. Gunner, who completed her LKA questions between her wedding ceremony and reception!@ABIMcert pic.twitter.com/VZz18KNQl2

— Ari Elman, MD (@AriObanMD) July 30, 2023

Chapter 6: Looking back, Looking Forward

One of the very best decisions I ever made during college was to spend time doing something else before starting medical school. That one year — spent at a school in England, mostly teaching American literature to kids age 12-18 — was so rich with experience and challenges at my then tender age that it has greatly rewarded me many times over in the coming decades of my life.

Haven’t regretted it for a moment — even though it delayed medical training by 1 year, and hence meant missing out on being grandfathered in on lifetime certification in Internal Medicine. Oh well.

But despite my not regretting this 1-year delay, I can’t help wondering if the ABIM MOC is really the best way to make sure that doctors stay up to date. Couldn’t we do something less onerous? Less expensive? Something tied more closely to the actual clinical practice we do every day, adapted for each person’s particular patient profile? Something linked to existing CME requirements and state licensing? A competing credentialing process, the National Board of Physicians and Surgeons (NBPAS), started in 2015, and has gained some traction. Certainly it has its strong supporters.

In summary, it really does seem like it’s time for a change.

What do you think?

August 18th, 2023

My Vote for the Weirdest Antibiotic on the Planet

Textile Dyeing Machine, 19th Century.

If you’re an ID doctor, there’s an excellent chance you’ve treated patients who have non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) with clofazimine. In fact, based on a poll done with the utmost scientific rigor, it’s well more than half of you.

And if you’re not an ID doctor, there’s a decent chance you’ve never even heard of it — clofazi-what? This is hardly surprising, since it gets my vote as the weirdest antibiotic out there. Of all the drugs we use in ID, clofazimine has the highest ratio of strange qualities to proven usefulness. Plus, it’s fun to say.

Allow me to share why it’s so unusual.

It’s been around a long time.

First synthesized in 1954, it initially held promise as an anti-TB agent, but it didn’t work very well. Later observations found that it was useful for treating leprosy, which is what led to FDA approval in 1969, under the brand name Lamprene. I don’t imagine there was much of a direct-to-consumer marketing effort when this blockbuster was released.

Since in vitro testing also suggested activity against non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) — for which treatment options have always been limited — ID clinicians regularly used clofazimine for years, including both for disseminated M. avium complex (MAC) disease in patients with advanced HIV disease and for pulmonary disease from NTM in immunocompetent hosts.

My first prescriptions for clofazimine were written in the early 1990s for both of these indications. I felt like I’d really arrived in exotic ID Land, writing for this strange drug used for leprosy. Wow.

Despite its approval over a half-century ago, you can’t just prescribe it anymore.

For reasons likely having to do with profit (or the lack thereof), in 2004 the drug disappeared from pharmacies. But it remained an essential drug for the treatment of leprosy in government-funded programs, so the company (Novartis) continued to manufacture it on a limited basis for this indication only.

This put us non-leprosy clofazimine prescribers in a bind. Azithromycin and clarithromycin had come along, greatly improving outcomes for treatment of these difficult bugs. But some MAC isolates and many strains of M. abscessus have macrolide resistance.

Certain enterprising patients heard the drug was still available in Canada (I wonder who told them … hmmm), but that door closed too.

But clofazimine remains widely available in many countries with high TB incidence. One colleague told me it can be purchased in India in most pharmacies for “cents”. It really is striking how often mycobacterial diagnostics and therapies are often more accessible in resource-limited countries than here.

But you can still get it here — warning, the process is not for the paperwork-averse.

Initially, the National Hansen’s Foundation distributed clofazimine on a very limited basis using what’s called a single patient investigational new drug (SPIND) program overseen by the FDA. That changed in 2018, and now Novartis runs this program.

These expanded access programs are in reality clinical research studies — enough so that the clofazimine program appears on clinicaltrials.gov, and approval will be required by a local Institutional Review Board (IRB). That clinicaltrials.gov link contains the critical information about how to get started, which is to email or call the company stating you have a patient who needs clofazimine. They will follow up with a series of essential steps before you can get the drug for your patient — here’s an (old) summary that’s no longer quite accurate but captures the basics.

You certainly won’t find this information on the Novartis site, or at least I couldn’t. Maybe it’s there somewhere.

What’s it like to go through this clofazimine approval process? As the site principal investigator for this program at our hospital, I can attest that Dr. Joseph Marcus provides here a highly illustrative video:

Did a SPIND for one pt at my institution as a first year attending and coordinating everything felt like a final exam/obstacle course of everything I learned in fellowship pic.twitter.com/H1Wc38cr3d

— Joseph Marcus (@JosephMarcusID) July 20, 2023

Hey, there’s a reason why we’re the Paperwork Champs! If it weren’t for the help of our research pharmacy and regulatory coordinator (thank you, Maria and ID pharmacy team!), I never could do this in a million years.

The drug looks active in vitro, but we really don’t know if it works.

Some reference labs will run clofazimine susceptibility testing on NTM isolates and report minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs), but also add cautionary comments about the lack of standardized MIC breakpoints. In other words, lower MIC numbers seem better — and the results usually are low — but we really don’t know how this correlates with the drug’s clinical activity.

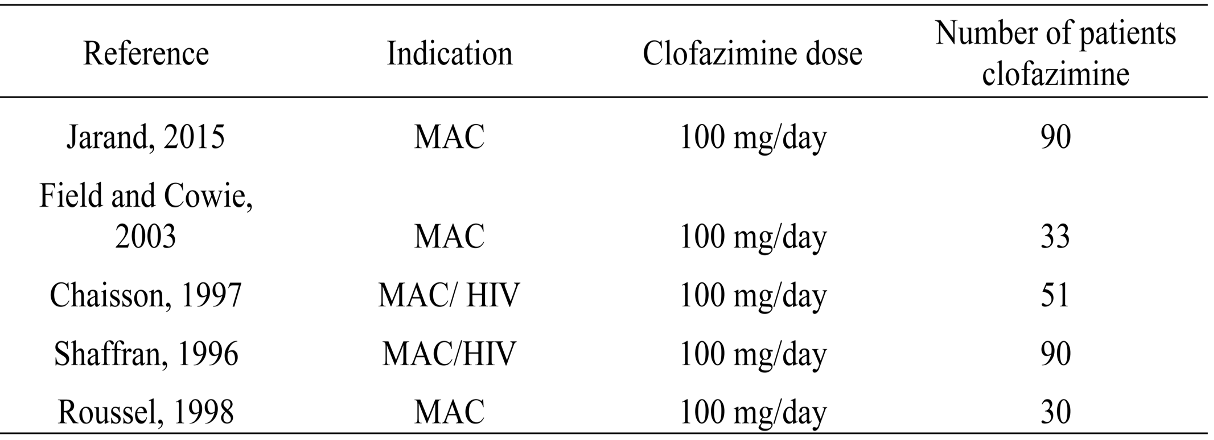

In addition, prospective data on clofazimine treatment in humans are incredibly sparse — and that’s being generous. From an informational slide set provided by Novartis comes this summary table:

The first study on this slide gives us probably the strongest favorable data — not only does it have only 90 treated patients, but it’s also not randomized and retrospective.

The slide also includes this statement:

No properly designed randomized controlled trials (RCT) have been reported to evaluate the role of clofazimine in the treatment of NTM infections.

Agree 100%. And while there are numerous other published studies besides those on this table, most are case series, not comparative clinical trials.

One possible reason for the lack of good data is the heterogeneity of people who have NTM pulmonary infection, ranging from asymptomatic colonization to progressive, life-threatening disease. Plus there are hundreds of different NTMs, and they can infect other sites, not just the lung.

As a result, this is a very challenging disease to study prospectively. One ongoing clofazimine treatment study opened in 2016; it has a sample size of 102. It still has not been completed.

The end result of this knowledge gap on the efficacy of clofazimine was succinctly put by Dr. Cam Wolf, who wrote:

For these infections, it’s nigh on impossible to tell if clofazimine is the difference maker.

Yep.

But this might change soon. There are other ongoing clinical trials of the drug, with the caveat that most of them involve tuberculosis, not the NTM we more often treat here.

Two randomized clinical trials of clofazimine for MAC in HIV found that clofazimine-treated participants had a higher mortality rate.

In people with advanced HIV disease and disseminated MAC, treatment with clarithromycin, ethambutol, and clofazimine was compared to clarithromycin and ethambutol alone. Mortality was 61% in the clofazimine three-drug group versus 38% in the two-drug group.

(Reminder, the pre-ART era in HIV was grim — and tragic.)

Baseline differences between the two groups, with higher levels of infection in the clofazimine recipients, could explain these unfortunate results — but it also could have been an adverse effect of clofazimine, which has in vitro anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects on both T-cells and monocytes/neutrophils. Could that explain the negative results in this highly immunocompromised group?

A second study in a similar population compared a three-drug macrolide-containing treatment with a four-drug non-macrolide regimen with clofazimine; survival was longer in the former. In this trial, it’s hard to blame the clofazimine, since only the three-drug group received a macrolide, the most active drug for MAC.

Limitations in these studies notwithstanding, we nonetheless generally avoid clofazimine in these very sick people with HIV.

How these discouraging study results inform the proper use of clofazimine in most patients with NTM infection treated today is anyone’s guess. Your typical pulmonary NTM infection case — not immunosuppressed, no dissemination — is worlds away from a person bacteremic with MAC, untreated HIV, and a CD4 cell count <50.

Still, it’s a concern.

We don’t know how it works.

That is, if it works.

But let’s assume it does. The two most commonly cited mechanisms are redox cycling and membrane destabilization and dysfunction. Not particularly strong in either biochemistry or molecular biology, I will share this erudite summary of the latter hypothesis from an excellent review:

This contention is based on the study by Baciu et al., who reported that cationic amphiphiles such as clofazimine partition rapidly to the polar–apolar region of the membrane, where, at physiological pH, the protonated groups on the drug catalyse the acid hydrolysis of the ester linkage of the phospholipid chains. The consequence is the production of a fatty acid and a lysophospholipid, both of which possess antimicrobial activity.

Those are sentences I never could have written. Fortunately, one doesn’t have to understand the mechanism of an antibiotic to use it.

Clofazimine has one common and very strange side effect — and a few others that are less common but very important.

The most famous side effect — or infamous, if you don’t like it — is skin darkening. It occurs in most people, is exposure-related, gradual in onset, and takes on a variety of different hues, from barely noticeable to quite dramatic.

For some, it’s quite flattering, if emulating sun exposure is the desired effect. “My friends all ask me where I’ve been this winter for my suntan,” said one of my patients, as Boston’s winter rays could never produce that warm glow. She likes it.

But for others, it just looks … strange. Watch out if you combine clofazimine with omadacycline (as we increasingly do with treatment of M. abscessus), and add a dose of strong summer sunshine. Covering arms and legs and wearing a broad-brimmed hat are both highly recommended! Fortunately, the skin darkening slowly wears off after the clofazimine is stopped.

Note that the darkening can occur in mucosa, conjunctiva, and body fluids too. Other skin side effects are excessive dryness and generalized pruritus. These dermatologic side effects could be one motivator behind the ongoing study of inhaled clofazimine, which presumably would avoid this toxicity.

Cases of torsades de pointes due to QT prolongation have been reported, as well as a serious syndrome of crystal deposition in intestinal mucosa, the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes. Suspect this crystal deposition problem if a patient on clofazimine develops worsening abdominal pain, and stop the drug immediately. Both the QT prolongation and the crystal deposition are more likely with higher doses.

So there you have it: clofazimine in all it’s extraordinary weirdness, hope I’ve convinced you.

Let’s hope we get some more data on the safety and efficacy of this drug sometime soon — and, if the results are favorable, the hurdles to using it finally come down. Our patients with NTM infection need all the help they can get!

August 9th, 2023

Really Rapid Review — Brisbane IAS 2023

Lamington National Park, Queensland.

You’ll find some conference highlights listed below from the 12th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science (or IAS 2023), which took place in lovely Brisbane — where the late July weather was delightful, the ubiquitous ibis was the local nuisance bird, and the riverside parks went on and on and on.

Some might wonder if I can still use the patented, trademarked, and copyrighted Really Rapid Review™ title when I’ve been home from Australia for a whole week. I vote yes — after all, I lost a whole day getting there, and deserve some of that time back. No, my Saturday, July 22, did not exist.

Most links will bring you to the invaluable natap.org site, long may it exist in its delightfully retro late-1990s format.

- Pitavastatin reduced cardiovascular events in people with HIV at low- to moderate CV risk. Yes, I already discussed it in detail, but how could I not at least mention this large, randomized clinical trial? It was the biggest story of the conference, which strangely was put in one of the smaller conference venues. People were literally sitting in the aisles, standing outside, clamoring to get in. Go figure.

- Prolonged ART-free HIV suppression occurred in a person treated with a stem cell transplant from a donor with wild-type CCR5 receptor status. Whether this case will be durable or ultimately have virologic rebound like the Boston patients remains to be seen. “Remission” (no detectable replication competent virus in blood or sampled tissues) is now at 20 months off ART and counting.

- Australia continues to be a model for HIV care and prevention. Their HIV care cascade exceeds 90-90-90% (diagnosed, started on treatment, suppressed), and they also have widely adopted preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Anecdotally, some HIV specialists in major urban areas say they rarely see new diagnoses. Imagine!

- 78% of the women in a large study of PrEP chose injectable over oral PrEP after the blinded, comparative phase of the trial ended. HPTN 084 compared TDF/FTC to injectable cabotegravir in women at risk for HIV; cabotegravir was significantly more effective. These results raise the question of whether cabotegravir for PrEP would be more widely used here if logistical and cost barriers were lower — I suspect yes.

- Stay tuned for updated information on prevention of gonorrhea with the meningitis B vaccine. In the ANRS DOXYVAC study, the factorial design randomized participants to doxycycline PEP and/or the meningitis B vaccine or neither. Though both interventions were reported at CROI 2023 to be significantly protective against gonorrhea in the interim analysis, investigators observed a discrepancy between the interim meningitis B vaccine results and the complete analysis — hence we await review and reporting of the final results.

- At Fenway Health (an LGBTQ Care Center in Boston), they have started using doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs). I suspect most of us have also begun offering this (I have), in particular to those with recent bacterial STIs. Guidelines endorsement coming soon, I hear.

- At 48 weeks, doravirine/islatravir was non-inferior to bictegravir/FTC/TAF as initial therapy. One versus zero participants developed treatment failure and resistance. No differences in weight gain (roughly 3 kilograms). Because the 0.75-mg daily dose of islatravir was used, CD4 response was blunted in that treatment arm. This comparison is now being repeated with 0.25 mg/daily islatravir dose; it will be interesting to see if virologic responses are as good.

- The key doravirine resistance mutations occurring in prospective clinical trials were V106A/M and F227C/L/R. These aren’t the only mutations that lead to doravirine resistance (notably Y188L and M230L do as well), but in the rare patient with virologic failure on doravirine-containing regimens, these two are the most likely to occur — and they don’t lead to cross-resistance with efavirenz or rilpivirine. Memorize these mutations, impress your friends!

- DTG/3TC was non-inferior to DTG + TDF/3TC in treatment-naive PWH, even without baseline resistance testing. 30% had HIV RNA >100,00, 21% CD4 <200. No treatment-emergent resistance. The study was slightly underpowered (n=214), but it highlights how rare transmitted 3TC or DTG resistance is, fortunately enough.

- People with virologic failure on DTG-based three-drug regimens had a high level of resuppression after adherence counseling. The exceedingly low rate of resistance selection with these DTG-based regimens likely explains the favorable results, which obviate the need to switch treatment. Suspect strongly these results apply similarly to BIC/FTC/TAF treatment, at least based on similarly low incident resistance and anecdotal experience.

- In treatment-experienced persons with HIV (PWH) with a history of treatment failure but current virologic suppression, switching to DTG/3TC was successful even with known 3TC resistance. 50/100 participants had documented M184V mutations. These results notwithstanding, until there’s a fully powered study evaluating this question — and why would we do that? — my view is that DTG/3TC has been extensively tested in people without M184V, and this is the population best suited to this switch strategy. By the way, this study is called SOLAR-3D, not to be confused with the SOLAR study of CAB-RPV.

- Switching stable PWH with integrase-inhibitor weight gain to darunavir/cobicistat/FTC/TAF did not reduce weight. Right now, it’s looking like the only regimen switches that may induce weight loss must involve a TDF-based treatment — which has its own toxicity issues (renal, bone), especially in older patients.

- For treatment of hepatitis B and HIV co-infection, BIC/FTC/TAF and DTG + TDF/FTC were both effective. These 96-week results continue to show certain endpoints favoring BIC/FTC/TAF, most notably HBEAg loss and seroconversion. But the DTG + TDF/FTC arm has “caught up” to the BIC/FTC/TAF arm in hepatitis B viral suppression, which happened faster in the TAF treatment arm.

- In a randomized trial comparing BIC/FTC/TAF to CAB-RPV, patient-reported outcomes favored long-acting injectable treatment. These results recapitulate several prior analyses with similar findings, which show that if people want to take injectable therapy, they’re happier once they do so. We could interpret these findings as either reassuring or a “self-fulfilling prophecy” — but how about both? And this, by the way, is the other SOLAR study.

- In a heterogeneous population (735) of PWH with viral suppression on three-drug therapy, switching to DTG plus either 3TC or RPV was safe and effective. Unlike in the phase 3 studies of these treatments, 50% of the population had a history of drug resistance mutations, so this expands the population potentially eligible for using two-drug therapy. Assume (hope) that they did not have primary mutations to either of the two drugs in the given strategy!

- In a small, comparative, matched study, PWH and diabetes mellitus (DM) lost significantly more weight on GLP-1 receptor agonists than people with DM alone. Our limited experience in clinical practice certainly shows this class of drugs leads to weight-loss in PWH. Could GLP-1 agonists be particularly effective in our patient population?

- In treatment-naive people starting antiretroviral therapy (ART), DTG-based regimens were associated with incident hypertension, especially when combined with TAF. This analysis from the NAMSAL and ADVANCE studies also showed that hypertension treatment (available to the ADVANCE study participants) was quite effective. As noted here and in a bunch of other studies looking at hypertension and association with specific ART, it’s tricky to disentangle this effect from differences in weight gain — a well-known trigger of high blood pressure.

- New onset diabetes was associated with current integrase strand inhibitor (INSTI) use, even when controlling for BMI. As noted by some HIV specialists, this same cohort found an association between INSTI use and cardiovascular disease — an association later refuted by an analysis controlling for baseline CV risk factors.

- Bictegravir exposure was reduced in pregnant women taking BIC/FTC/TAF during the second and third trimesters. The median trough was still 6-7 times higher than the inhibitory quotient, and none of the women experienced virologic rebound or failure; the only participant with notably low levels was taking concomitant calcium and iron supplements. These results support the decision to continue BIC/FTC/TAF in women who are found to be pregnant while receiving this regimen.

That’s a wrap! What did I miss?

After the conference, we went hiking in Lamington (see picture above) and Springbrook National Parks. So beautiful! Saw wallabies and cockatoos and kookaburras!

Now, if only someone could come up with a cure for jet lag …

July 26th, 2023

REPRIEVE Trial Highlights Shift in HIV Care from ID to General Medicine

Australian White Ibis. Not an exotic bird in Brisbane!

The biggest news this week at the 12th IAS Conference on HIV Science here in Brisbane, Australia, was the results of REPRIEVE, a large randomized clinical trial conducted in people with HIV.

It’s not a study of novel antiretroviral regimens, or of treatment or prevention of opportunistic infections, or of an HIV eradication strategy using latency-reversing agents or immunotherapy.

Nope — it’s a study of cardiovascular prevention with an exotic class of drugs called statins.

(Sarcasm alert.)

That’s right, statins. As noted here several years ago, REPRIEVE recruited stable people with HIV age 40 or older, on ART, and at low to moderate risk of cardiovascular disease — people for whom a statin would generally not be prescribed. Since HIV confers up to a 2-fold increased risk of CVD compared to people without HIV, the hypothesis was that a statin would reduce the risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event compared to placebo.

The drug chosen was pitavastatin, since it doesn’t interact with any ART regimen. 7769 people enrolled at study sites throughout the world, with diverse demographics and broad geographic representation. It was a “simple” (nothing this size is really simple) study design, with randomization to pitavastatin or matching placebo.

After a median follow-up of approximately 5 years, the data and safety monitoring board overseeing the study stopped the study early because of a highly significant benefit of pitavastatin — the risk reduction for pitavastatin vs. placebo was 35%.

REPRIEVE: Significant decrease in major adverse cardiovascular events with pitavastin.

RCT trial enrolled only low-to-moderate CV risk PWH, for whom a statin might not otherwise be prescribed.

Important clinical trial with direct relevance to pt care. https://t.co/dVtQgtAGhz pic.twitter.com/eI5ZeOvzcB

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) July 24, 2023

The benefits of pitavastatin were consistent across baseline demographics and medical issues, with point estimates favoring the intervention over placebo in virtually every group. Overall, this translated to a 5-year number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent a major cardiovascular event of 106 (95% CI, 64 to 303), in line with or better than other widely adopted interventions (treatment of hypertension, or aspirin) to prevent this complication.

Presenting the study results to a packed conference room at the IAS meeting, lead investigator Dr. Steven Grinspoon highlighted several uncertainties that await further study, among them:

- What is the mechanism of this risk reduction? The magnitude was greater than would have been expected solely based on the lipid-lowering effect, implying the anti-inflammatory property of the statin also played a major role.

- Is the higher incidence of diabetes with statin therapy enough to counter any of these favorable results? This risk is in line with what has been observed in other statin studies, though in some regions where diabetes is very common, this could be an issue.

- Are there certain subgroups likely to have more or less benefit? Oddly, people with hypertension did not appear to benefit as much — probably just a fluke. And we’ve been tracking certain antiretrovirals with CV risk for many years; it will be fascinating to see if any specific regimens confer excess risk, with or without pitavastatin.

- How will we interpret absolute vs. relative risk in clinical practice? Not surprisingly, those at lowest cardiovascular risk have a higher NNT (200) to benefit one patient. Even if pitavastatin lowers the risk by 35% in this group, does the low absolute risk make it worthwhile to add another drug?

- Would another statin have comparable results? After all, pitavastatin is rarely prescribed today, as generic statins are much less expensive. The drug is also not available in many countries.

- What was the impact of COVID-19 on outcomes? The study started enrolling in 2015, and completed in 2023. That means a lot of participants got COVID-19 during the study, both before and after vaccines became available.

- Would we get the same result in people without HIV? Not saying that REPRIEVE is going to answer this question — just wondering. The “put statins in the water” camp certainly believe this!

Numerous substudies are ongoing or planned to try and tease out the answer to these and other questions. As we await them, we can congratulate Steve (whom I’ve known for years as a thoughtful and collaborative investigator) and his large research team for completing this remarkable study.

We can also again reflect on how far we have come in HIV medicine in making PWH rock-solid healthy, so that non-ID health issues, in particular diseases of aging, dominate their wonderfully long lives. Steve is an endocrinologist; the protocol co-chair (Dr. Pamela Douglas) is a cardiologist. And while there are ID doctors on the leadership team (hello Drs. Carl Fitchenbaum and Judy Aberg!), it’s notable that major advances in HIV research have drifted away from an ID doctor’s typical areas of focus.

More importantly, a conversation about the risks and benefits of statin use is mainstream general medicine discourse, something that happens thousands if not millions of times a day in primary care. Stable people with HIV are overwhelmingly just that — stable.

These provider-patient discussions will have nothing to do with complex resistance genotypes, novel antiretroviral drug classes, or life-threatening opportunistic infections. About the most complicated aspect of this discussion from the ID/HIV standpoint will be the drug interactions if your patient is still on a regimen containing the pharmacokinetic boosters ritonavir or cobicistat, a rapidly dwindling patient group, and you choose to use atorvastatin.

(That’s easy — just start with a low dose, 10 milligrams daily.)

Now I still enjoy the general medicine that comes with longitudinal HIV follow-up, but I do understand if some ID doctors opt out. And whether these statin yea-or-nay discussions should be in the domain of ID specialists, or general internists, or both, is another topic entirely.

Notably, Australia has never put HIV care in the sole domain of ID specialists. It’s a model we should look at increasingly over the next years-to-decades, thanks to the success of HIV treatment.

July 5th, 2023

The Yin and the Yang of Cabotegravir-Rilpivirine: Part Two, the Limitations

Tip of Needle and Stinger of a Bee, from Martin Frobenius Ledermüller’s Microscopic Delights (1759–63).

In the last post, I cited examples of patients who are doing much better now because they are on long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine (CAB-RPV). One of these patients said he preferred it because it’s “simpler,” by which he meant he no longer had to go to the pharmacy to refill his medications each month.

I’ll grant for him it’s simpler, but for the rest of us? Because when I teach ID fellows about antiretroviral therapy, I have a slide that is entitled “Limitations of CAB-RPV.” It includes nine bullet points, meaning not only am I breaking the rules of good slide-making, but more importantly, it’s proof that CAB-RPV is anything but simpler.

Here are the bullet points, with further discussion — because if you’re an ID/HIV doctor and don’t yet offer this treatment to your patients, it’s important that before you do so, you go in with your eyes open:

Complex logistics to implement and monitor. Based on an optimistic interpretation of the voluminous direct-to-patient advertisements for the regimen, some might think that doctors can just write a prescription for CAB-RPV and voila, a patient can go to the pharmacy, pick it up, and get started.

Think again.

At our site, we have a dedicated, energetic, and wonderful nurse practitioner who took making this treatment option available to our patients an important priority. Without her leadership, it’s no exaggeration that we never could have done it (thank you, Cathy!). Chatting with colleagues around the country, I’ve heard that all these clinics that offer CAB-RPV have someone who took this on as their primary responsibility. It could be a nurse as in our case, or a doctor, or an ID pharmacist, or a case manager. I guarantee that all these fine people have in common great administrative skills, executive function, and perseverance.

In short, if you don’t have a “champion” going through the logistics of how you’re going to get the medications to your clinic and administer them, you won’t get very far. If you want to supplement this post with a comprehensive video covering the myriad issues you need to consider before getting started, I highly recommend this outstanding summary by the Mountain West AIDS Education and Training Center, with Ji Lee, PharmD.

It’s over 20 minutes long. “Simpler” indeed.

Risk of treatment failure with resistance, even with adherence to the regimen. True, the risk is small (around 1%) — but we have become accustomed to guaranteed treatment success with dolutegravir- and bictegravir-based regimens, with essentially zero risk of resistance with good adherence. Not only can CAB-RPV treatment fail, but the consequences (integrase inhibitor and NNRTI resistance) means that boosted-PI regimens become the default option, with all their disadvantages.

An important paper recently appeared in Clinical Infectious Diseases highlighting risk factors for resistance derived from the clinical trials:

Virologic failure despite adherence to CAB-RPV is rare (1%), but it happens, with bad consequences (INSTI and NNRTI resistance). Risks:

– RPV RAMs

– Subtype A6/A1

– BMI > 30Really important paper in @CIDJournal, with lead author @profchloeorkin https://t.co/lopLUqmXjH

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) June 21, 2023

While some of these risk factors can be assessed or intuited ahead of time — for example, I won’t use this treatment in people with any NNRTI resistance, not just RPV resistance — and anecdotally treatment failure can rarely occur even in the absence of risk factors.

Cost. Cabotegravir-rilpivirine costs more than oral ART, which has become increasingly expensive, even when accounting for inflation. This has consequences for insurance coverage, and, as any HIV clinician can tell you, our treatments are now aggressively managed by many payers. With CAB-RPV, there is often a complex and lengthy benefits check and pre-approval process before the treatment can start.

And this cost issue only refers to the medications. It doesn’t account for the nursing, pharmacist, case manager, or physician time to get the approvals, to prepare the medications, to administer them, and to chase down people who miss appointments.

All that takes time — time that could be spend doing other things. As economists will remind us this is a cost too, especially in a time of widespread healthcare provider shortages. I am aware of at least one HIV clinic that has had to limit their new patient enrollments for CAB-RPV due to this shortage.

Injections must be delivered by a healthcare provider. CAB-RPV administration is not like a simple insulin injection or flu shot — watch an instructional video, you’ll see what I mean. (Go to Video Library, “How to administer injectable medicine”).

In addition, most practices carry a very limited supply of medications available for in-office injections. One of my patients, a Boston “snowbird” spending the winter in a warmer southern state, contacted me saying he wouldn’t be back in time for his injections, but he was confident he could get it from a primary care clinician he sees sometimes when he’s down there. I told him that unless this doctor had a large practice of people with HIV (they didn’t), there was zero chance this would be possible — which turned out to be the case. He went back on oral ART until April, when he returned to Boston.

Fortunately, the company that makes CAB-RPV posts a locator for alternative sites for receiving the injections, which is a great idea both for when patients travel and for clinics that don’t have the resources to offer this treatment themselves. It’s not clear how often people are using these sites, however, and availability is limited. For example, the only one I see in the Boston-area requires a trip to Providence, around 50 miles away.

Frequency of visits. Most people receive their CAB-RPV at their doctor’s office, coming in six times a year for the two injections. Before that, while on stable ART, visits typically occurred every 6 months, or even annually.

Allow me to do the calculation: that’s four or five extra trips into the clinic each year. Not easy for many people, and an additional cost (parking, transit, time out of work, away from family).

Injection site reactions. Like anything that involves a needle piercing the body, these shots hurt some people more than others. In the clinical trials, most reported them as mild or moderate in severity, but a small number did find them severe enough to stop treatment. This is consistent with our experience in clinical practice.

Pain relievers, ice- or warm-packs, stretching all can help. And patient education ahead of time is critical!

Limited data for patients with resistance, history of treatment failure, or viremia. So far, the exciting data on using CAB-RPV in people who are viremic and can’t take oral ART has not been replicated elsewhere in a prospective study — just anecdotes here and there, as in the 4th case I cited in the previous post. As a result, use of CAB-RPV is explicitly not recommended in treatment guidelines for virologic failure — even though such a practice would arguably be even more transformative than CAB-RPV’s current indication.

Also applicable for everyday patient care would be a large cohort of people with a prior history of treatment failure, but no documented integrase inhibitor or NNRTI resistance. When will we see those data?

Not recommended during pregnancy and breast feeding. As with every novel HIV treatment, this important patient population not been prospectively studied, at least not yet. But given the increased volume of distribution seen during pregnancy, and the low resistance barrier of rilpivirine, I would strongly discourage its use.

Does not treat or prevent hepatitis B. One of the great benefits of tenofovir is that it’s also our best current treatment of hepatitis B. Switching to CAB-RPV removes this advantage, and indeed one of the participants in the licensing trials contracted hepatitis B during the study.

Lesson for us — make sure to check hepatitis B status prior to starting CAB-RPV, and update vaccination as needed.

These limitations to CAB-RPV are understandable. After all, this is the very first long-acting ART option, and the fact that we have it at all is remarkable. Furthermore, we can expect progress in this area as other compounds become available, preferably some that can be administered even less often, or at home.

But for now, all of us doing HIV care must dial up our counseling skills when patients ask whether they should switch to long-acting injectable ART — and they will ask, since the advertising bombards them regularly. As noted previously, this treatment option gives us a great chance to engage in shared decision making, to elicit patient preferences and to deliver information at the appropriate level of medical literacy.

They should hear about the benefits, and the risks, and the practicalities. Give them plenty of time to ask questions and join them in the decision process of whether it’s a good idea to switch.

Then you should both watch this video, because even with these limitations outlined here, it’s truly a miracle how far we’ve come with HIV treatment. And about that we can be very grateful!

(Thanks to Dr. Darcy Wooten and Cathy Franklin, NP for reviewing this post, and Mass General Brigham for producing the video.)

June 30th, 2023

The Yin and the Yang of Cabotegravir-Rilpivirine: Part One, the Good News

British advertisement, 1950.

Long-acting cabotegravir-rilpivirine (CAB-RPV) is the biggest advance in HIV therapeutics in years. It’s also creating quite the challenge for ID and HIV clinicians, which makes its availability a fascinating example of the importance of education, patient communication, and shared decision-making.

This post will be the good news about this groundbreaking treatment; in the next post, I’ll give the other side of the story.

For those of you who don’t do HIV treatment on a regular basis, here’s a brief summary of its development and intended use. In two prospective clinical trials (ATLAS and FLAIR), people with virologic suppression and no history of treatment failure or HIV resistance were randomized to receive their current daily oral ART or switch to once-monthly injections of cabotegravir (an integrase inhibitor) and rilpivirine (a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor already available in pill form).

The results showed that CAB-RPV was noninferior to oral ART. Later, a study (ATLAS-2M) demonstrated that these two injections could be given every 2 months. After a delay of several months due to manufacturing issues, it was FDA-approved in January 2021 as a switch strategy for “virologically suppressed adults.”

Seems simple, right? A straightforward option to offer people with HIV who no longer want to take their daily pill or pills. Progress!

Indeed, in the clinic for some patients, offering them this option has been wonderful. For reasons often having to do with convenience, privacy, stigma, or pill fatigue, they find the injections a tremendous improvement in their quality of life.

Some examples, drawn from our clinic (certain details changed for confidentiality):

- A person who works nearby and takes no other medications, she loves just dropping by every 2 months to get her shots — she forgets entirely between visits that she has any medical problems at all.

- Someone who lives with his family hated that his HIV medications had to be hidden since he wasn’t ready to disclose HIV to them; now he doesn’t worry about that at all.

- Another describes CAB-RPV as “simpler” — which is his code for “I no longer have to go to the pharmacy each month and ask for a refill of these meds I’m embarrassed I need to take.”

- A man who never could take oral ART consistently — with a declining CD4 cell count and multiple symptoms suggestive of advancing HIV disease — now is virologically suppressed and healthier than ever on monthly injections of CAB-RPV.

I have no doubt that the first three patients above would be fine on oral ART had CAB-RPV never been approved. But they are so much happier now.

And the fourth? It could have saved his life, or prevented HIV transmission to his partner, even though use of CAB-RPV is explicitly discouraged in HIV treatment guidelines for patients just like him. Trust me, like most HIV treaters out there, we would only use CAB-RPV for people with viremia when all other efforts to get someone on lifesaving treatment had failed.

As these examples demonstrate, this is what a big advance in ART looks like, and we’re all better for it!

Time to celebrate with a spectacular classic clip that I happened upon while you-tubing deep into the evening. Warning — don’t try this at home!

(Apparently they filmed this in one take. Amazing.)

Next post — the limitations of CAB-RPV. Sneak preview: there’s a lot to consider before offering this to your patients.

June 15th, 2023

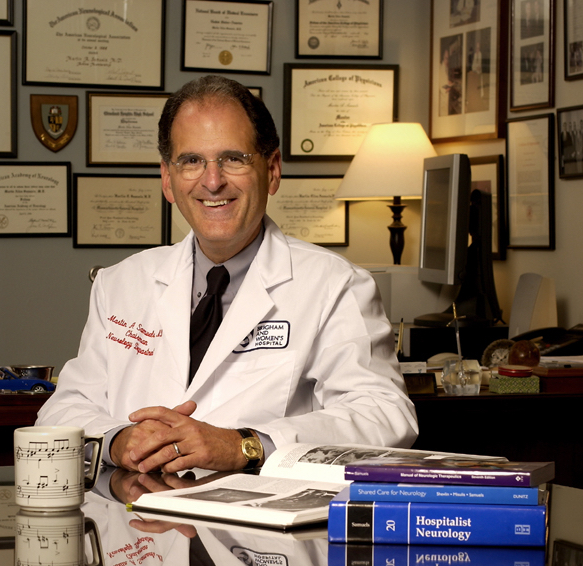

Clinical Teaching at the 99.9th Percentile: Dr. Martin (Marty) Samuels

One of the true joys of practicing at academic medical centers is working alongside great clinical teachers.

One of the true joys of practicing at academic medical centers is working alongside great clinical teachers.

No one exemplified this talented group better than Dr. Martin (Marty) Samuels, former chief of neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (where I work), and professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School. He was quite simply the best clinical teacher I’ve ever encountered.

Marty died last week, and our world is sadly now a less interesting and less fun place. What made him so special? Here are a few thoughts:

He had endless enthusiasm for clinical neurology. You could just see his eyes light up when a resident presented him a case. The combination of clinical problem solving together with a group of trainees eager to learn visibly energized him.

And the enthusiasm didn’t end with neurology. He embraced all of medicine, including its history, which he loved to connect to neurology — cardiology, nephrology, hepatology, ID. Watch him discuss a case of an older man with mental status changes during a “virtual” Neurology Morning Report, done on Zoom during the pandemic. He deftly describes his clinical reasoning, interweaving Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, pathophysiology, and his experience working with the great British hepatologist Dame Sheila Sherlock.