An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

June 4th, 2011

HIV Epidemiology and Something Even Many Smart Medical Students Don’t Know

Periodically I like to give an informal quiz to the medical students about HIV epidemiology. It’s a multiple choice question that goes something like this:

Periodically I like to give an informal quiz to the medical students about HIV epidemiology. It’s a multiple choice question that goes something like this:

Based on the recent epidemiology of HIV in the United States, in what group are new cases of HIV infection rising the fastest?

- Men who have sex with men (MSM)

- Injection drug users (IDUs)

- Heterosexual women

- Some other group

(Correct answer: #1.)

Now these are smart kids. Many of them have done impressive things before starting med school, including a bunch who have even worked in the HIV field (especially global HIV). Yet despite these brains and experience, you’d be amazed how often they choose the wrong answer, most commonly choosing #3 (a group in whom incidence is essentially flat or declining) or #2 (injection drug use HIV in the USA is, thankfully, disappearing).

On the 30th Anniversary of the first report of what is now known as AIDS, the MMWR has released its latest HIV Surveillance report. And, as in pretty much every year for more than a decade, here are the facts:

Surveillance data show that the proportion of HIV diagnoses occurring in MSM continues to grow. HIV incidence among MSM has increased steadily since the early 1990s. In 2009, MSM accounted for 57% of all persons and 75% of men with a diagnosis of HIV infection... Syphilis and gonorrhea are endemic among MSM; outbreaks or hyperendemic sexually transmitted infections have been reported from many communities where HIV infection also is prevalent, further increasing the risk for acquiring and transmitting HIV.

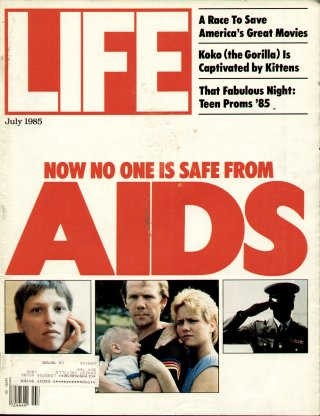

I’m not sure why this isn’t more widely known (certainly we HIV/ID specialists know it), but I have a theory. Sometimes a story has media “stickiness”, and once it’s out there, it’s hard to get rid of it. When AIDS first hit, it was overwhelmingly a disease of MSM and IDUs; quickly it became apparent, however, that it was a sexually transmitted infection so that women were at risk too. This was a big media story — famous Life Magazine cover shown above — and somehow this has never disappeared.

It’s kind of like, “tuberculosis is making a comeback in the USA” when, in fact, TB rates are historically low. The TB Comeback is just too sticky. Same thing with the generalized HIV epidemic in this country which, if you take a look at this incredibly cool map, has never happened.

Take home message: HIV prevention and testing efforts should be maximally deployed where the epidemic is still raging. Here in the USA, that means MSM and/or communities of color.

June 2nd, 2011

Original XMRV/CFS Paper Almost, Sort-of Retracted by Science

From the pages of Science

In this week’s edition of Science Express, we are publishing two Reports that strongly support the growing view that the association between XMRV and CFS described by Lombardi et al. likely reflects contamination of laboratories and research reagents with the virus … Because the validity of the study by Lombardi et al. is now seriously in question, we are publishing this Expression of Concern and attaching it to Science’s 23 October 2009 publication by Lombardi et al.

In the roughly year and half since this story first broke on XMRV as a possible cause of CFS, there have been literally dozens of scientific papers (published, unpublished, and presented), many editorial comments, conference proceedings — and probably thousands of blog posts (I’ve added to the traffic) and impassioned comments from people suffering from this condition.

As I’ve noted before, perhaps the best coverage in the non-medical/science press has been over here in the WSJ.

And while there is now significant “concern” about this XMRV/CFS association, there is little doubt about the need for more research on CFS. One problem is that the XMRV debate could become a distraction in the search for other possible causes, host factors, diagnostic tests, and treatments. Let’s hope that doesn’t happen.

May 18th, 2011

HIV Exceptionalism and the Department of Unintended Consequences

Quick question: If there were one piece of information — clinical or lab — that you would use to determine the quality of care in an HIV  program, what would it be? (Choose one.)

program, what would it be? (Choose one.)

- Rates of influenza vaccine administration

- Receiving PCP prophylaxis with CD4 < 200

- Adherence counseling before starting antiretroviral therapy

- Baseline toxoplasmosis serology

- Proportion of patients on treatment with suppressed viral load

Maybe I’m being presumptuous here, but one of these — virologic suppression — completely blows the rest of them away. Sure, the others are worthwhile, but data linking them to improved outcomes for people with HIV are either pretty weak (adherence counseling, flu vaccine) or nonexistent (toxoplasmosis serology).

Even the use of PCP prophylaxis for CD4 < 200, which was highly effective and prolonged survival in the pre-ART era, doesn’t come close to the benefits of effective ART. One paper even questions whether we need it, provided that the person is on fully suppressive HIV therapy.

So why bring this up under the title of “HIV Exceptionalism”? Because a certain unnamed institution in an unnamed city (hint: begin with “B”) cannot obtain the aggregate viral load data on their own patients as part of a quality improvement initiative.

The reason? Anything with “HIV” attached to it, you see, is privacy-protected information under Massachusetts Chapter 111, Section 70F, unless the patient provides written informed consent. No exceptions listed.

Which means that people with HIV can’t participate in this quality improvement program — in effect, are discriminated against — due to a law that in the post HIPAA era should not even be necessary, since all medical information is now considered confidential.

The state law on HIV testing and privacy, by the way, dates back to when HIV was called “HTLV-III”, and it’s showing its age. Fortunately, revisions to it are in the works that allow for appropriate testing, clinical care, research, and quality improvement.

Stay tuned.

May 17th, 2011

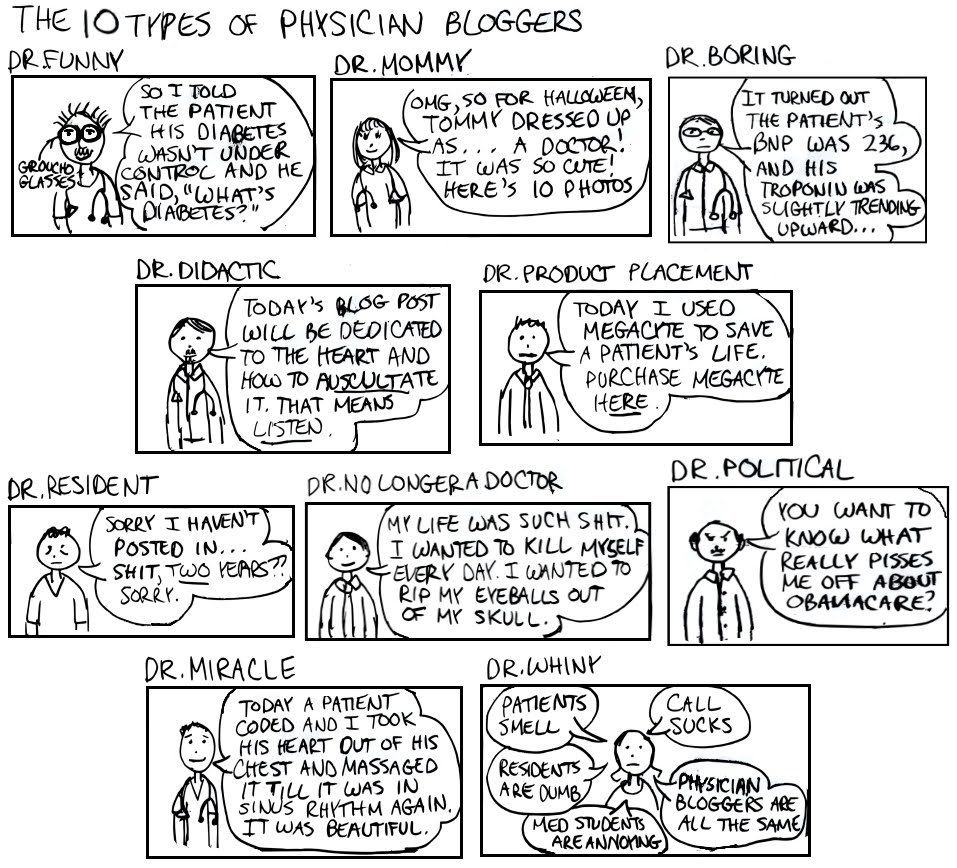

Physician Bloggers Categorized

About a year ago I linked this cartoon from “Dr. Fizzy”, and I’ve been a regular visitor to her site ever since.

About a year ago I linked this cartoon from “Dr. Fizzy”, and I’ve been a regular visitor to her site ever since.

Anyway, more kudos to her for this dead-on categorization of MD bloggers.

(I guess the British “spot-on” is a better choice for us docs.)

Not exactly sure where I fit in this list — yikes — but boy does she get it right here.

In fact, one could replace “The 10 Types of Physician Bloggers” with “The 10 Types of Physician Dinner Companions”, and you’d have a good description of how we MDs interface with the world in pretty much every setting.

May 9th, 2011

Routine Screening for Anal Cancer: Are We There Yet?

A paper recently published in AIDS evaluated the cost effectiveness of various strategies for anal cancer screening in HIV positive men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM).

The “bottom line” (ahem):

In HIV-infected MSM, the direct use of high resolution anoscopy is the most cost-effective strategy for detecting anal intraepithelial neoplasia

High-resolution anoscopy without any prior testing was the most cost-effective of 18 strategies assessed for initial anal cancer screening… This study suggests that direct use of HRA is a reasonable strategy for initial anal cancer screening in a population with a high prevalence of disease. Several other strategies were also effective at a moderate cost, including the one used in my own practice: initial anal cytology, with referral to HRA for individuals found to have atypical squamous cells (ASCUS) or greater.

We covered this area of controversy around a year ago on this site, at which time Joel Gallant admitted to an even less aggressive strategy — namely, not referring patients with ASCUS for HRA at all, but simply monitoring them with yearly pap smears.

His rationale?

My patients don’t enjoy going through HRA, biopsy, and ablation, the parallels between anal and cervical dysplasia aren’t perfect, and the protocols around anal Pap smear are written without much evidence backing them up.

As you might have guessed, I have tremendous ambivalence about what to do about anal cancer screening as of May 9, 2011 (today). On one side: this is a highly morbid (and potentially fatal) complication of HIV, a screening protocol, however vague, is out there, and there are advocates who strongly support screening.

On the other side are the issues cited by Joel, the lack of recommendations for anal cancer screening in published guidelines, and the fact that at one of my two practice sites, there has been no single provider who readily offers HRA.

Just speculation here, but on a national level, this last factor might be the most important driver in how often HRA is done at all.

And just like any situation where test availability drives volume, there’s something not quite right about that.

May 4th, 2011

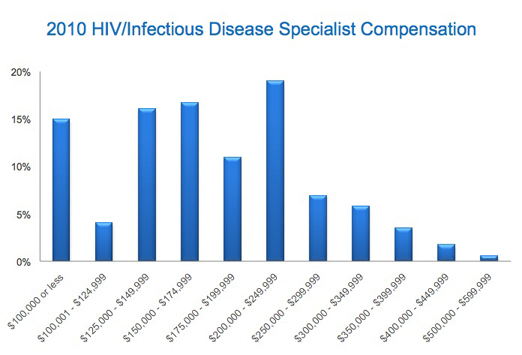

How Much Do ID/HIV Doctors Get Paid?

A long time ago, I was very close to becoming a Cardiologist. Really.

A long time ago, I was very close to becoming a Cardiologist. Really.

Even though my fascination with ID and microbiology started in medical school — and believe me, not much fascinated me in medical school — the fact that all the top residents in my program were going into Cardiology made me feel that somehow I should be doing this too. Plus, the guy who was Chief of Medicine was very influential.

When I came to my senses, and realized that I wanted to go into ID, there was a small problem — I had already matched in a Cardiology program. Hence I faced the tricky task of telling the program director, “Thank you very much for your kind offer, but I’ve decided I want to be an Infectious Diseases specialist.”

I remember his look of annoyance (understandable). It was soon replaced by one of disbelief. And then came a line I will never forget:

At least your motivation isn’t financial — ID doctors get paid s–t.

All of this came back to me when I read this fascinating survey over on Medscape on what we doctors get paid.

Some of the interesting results:

- Yes, ID specialists (median of $174,750/year) are at the lower end of the specialist scale. Other bottom feeders? Pediatricians (it’s a family thing), Rheumatology, Endocrinology, Primary Care …

- And the program director at my cardiology-fellowship-that-never-happened was right: Cardiologists are the third-highest-paid physicians (after orthopedic surgeons and radiologists), with a median income of $325,000. 20% of Cardiologists report making more than $500,000, while almost this many ID/HIV docs get < 100,000.

- However, despite this disparity, a higher proportion of ID docs (55%) than Cardiologists (45%) report they were fairly compensated. Is that because ID is the most fascinating field in medicine? And that an endocarditis case is surely more interesting than the simple plumbing they generally care for? (That was a joke. Some of my best friends are cardiologists.)

- Weird disconnect between geographic cost of living and salaries, with the lowest pay coming in the most expensive places to live. This is of course the complete opposite of salaries in business, banking, and law. So if you want your doctor’s pay to go further, don’t live in California or Washington/NYC/Boston!

Of course, as we tell our kids, when choosing a career, it’s not about being rich — it’s about being happy.

But if you want to be both rich and happy, the specialty-of-choice is clearly Dermatology — median annual income is nearly $300,000, and a whopping 93% said they’d choose the same specialty again, the highest of all the fields surveyed.

Acne treatment never looked so good.

April 28th, 2011

Hepatitis C Week is Upon Us

After many — and I mean many — years of telling patients that new hepatitis C drugs were “coming soon,” that time has finally come.

After many — and I mean many — years of telling patients that new hepatitis C drugs were “coming soon,” that time has finally come.

An FDA Advisory Panel yesterday favorably reviewed the HCV protease inhibitor boceprevir; today telaprevir got the same unanimous report. The FDA will certainly follow with approval for both drugs, and hence they will be available for actual use soon.

While these are undoubtedly huge advances for patients with HCV genotype 1 — who faced a 30-40% chance of cure with IF/ribavirin now, compared with up to 80% by adding one of the new drugs — many questions remain about how they will be used, and in whom.

In no particular order, and without even trying to be comprehensive, here are some of the “known unknowns“:

- How will clinicians choose between them?

- Is a 4-week lead in with IF/RBV (as was done with the boceprevir studies) necessary? Additionally, is it useful, by identifying “null” responders who will have a higher rate of developing treatment failure and PI resistance? Could starting all three drugs simultaneously improve outcome?

- How long should treatment be? Will this vary depending on HCV RNA kinetics from person-to-person? Seems like this is a situation ripe for sophisticated modeling, and that more frequent HCV RNA monitoring (especially early) will inform this decision.

- How will patients in the chaotic real world tolerate these drugs? Interferon/ribavirin is already no picnic, and adding these additional meds will mean additional side effects.

- Related: Besides the signature toxicities (telaprevir — rash and anemia, boceprevir — anemia and dysgeusia), what other side effects will appear with more widespread use? Note that it’s not a question of if these side effects will occur, it’s when will occur, and what they will be.

- How will resistance be assayed? Will genotype testing become commercially available? If so, what new combination of letters and numbers (i.e. mutations) will need to be memorized?

- How do these advances influence treatment decisions about the patients who don’t have HCV genotype 1, especially those with genotype 4? I suspect not at all, at least for now.

- How will compliance be with these three-times a day regimens? Will it improve over the course of therapy, or will patients get “pill fatigue.” We know they will get regular fatigue — I have yet to see a patient receiving interferon who didn’t mention this as a side effect.

- View from 20,000 feet: If someone is currently very stable — with low risk of HCV disease progression — should they “act now” or wait for even better, less toxic options? Given the huge effort in HCV drug development, how long before we have treatments for HCV that are comparably simple to HIV therapy? Is a single-pill combination tablet too much to ask? Remember, for HIV, such a treatment would have been unimaginable in 1996; less than 10 years later it was the mostly widely-used HIV combination in the country, and remains so today.

- Who will be the HCV Providers? Will the legacy of gastroenterologists’ leading the way in hepatitis therapy continue, or will this Infectious Disease finally be embraced by Infectious Disease Doctors? (Italics represent my view.)

- How much will the new drugs cost? Will they be covered for all patients? How about for those who have a favorable IL-28B genotype — and would be likely responders to IF/RBV alone?

- How will our HIV co-infected patients respond? Data are extremely limited — and the drug-drug interactions promise to be unbelievably complex. As of April 28 2011, we only have data on use of telaprevir with either EFV or ATV/r.

- How do you design an HCV clinical trial once these drugs are approved? Will all “control” arms now need to be IF/RBV + something-previr?

Answers to some of these questions will come with formal FDA approval, which will necessarily include some “package insert” indications for therapy.

But stay on your toes, because it seems highly likely that this is one therapeutic area in ID that truly lends itself to the cliche, “moving target.”

From the

From the