An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

February 7th, 2012

Chronic Fatigue: Is There Hope After XMRV?

I’ve been following the chronic fatigue/XMRV story from the start, which was compelling for several reasons, including:

- A potential cause was identified of a very debilitating, mysterious illness.

- Lots of very smart ID people (including some of my colleagues) studied it.

- Media coverage, notably from the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, was particularly skillful.

In that last vein, the Times today has a fascinating summary of the current situation for this once promising link.

In a word, the link is kaput.

After numerous investigators were unable to duplicate the original results, Science issued an “Expression of Concern” about the paper they had published in 2009. Then in late December, that paper was fully retracted by the Editor of the journal, as was a key supporting paper — really the only supporting paper — that had been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Could things get any worse? Of course. Here’s what’s come of the lead investigator in the original Science paper:

Dr. Mikovits left her position as research director at the [Whittemore Peterson Institute] in a dispute over management practices and control over research materials. The institute sued her, accusing her of stealing notebooks and other proprietary items. Dr. Mikovits was arrested in Southern California, where she lives, and jailed for several days, charged with being a fugitive from justice.

Yikes.

But even with all these clouds, there’s an important silver lining to all this news nicely articulated by a noted virologist:

“The disease had languished in the background at N.I.H. and C.D.C., and other scientists had not been paying much attention to it,” said John Coffin, a professor of molecular biology at Tufts University. “This has brought it back into attention.”

I couldn’t agree more. And with that greater attention, perhaps we’ll see some discoveries that really help people.

January 29th, 2012

Pre-Super Sunday Scombroids

Some quick ID/HIV links while we await big guys playing the big game with a big (or at least bigger) ball.

Some quick ID/HIV links while we await big guys playing the big game with a big (or at least bigger) ball.

- Did you see how this doctor cheated Medicaid out of more than $700,000 by prescribing HIV meds to people who didn’t have HIV? Not surprisingly, he’s going to jail. Proof that if there’s money behind a program — no matter how beneficial — someone will figure out a way to scam it.

- Not only is there barely any winter this year, but there’s hardly any influenza. Not a single state is reporting widespread activity. But Google Flu doesn’t think it’s quite so remarkable, especially compared to last year where flu season peaked in mid-late February.

- What we’re not getting in flu, however, we’re definitely getting in norovirus activity, at least here in Boston. Last week someone in our office turned the color of a bedsheet, then disappeared home, only to returned a few days later weak, tired and 10 pounds lighter. And she didn’t even get to go on a cruise, though maybe that’s a good thing this year.

- Good brief piece in the Times about men of a certain age getting HIV. As the author awaits the results of his test, he writes “I was feeling an incipient sense of . . . failure.” That part particularly rang true, based on my clinical experience — these men lived through the horrible early years of the epidemic, and they feel like failures to get HIV now, after all these years. Lots of self blame.

- How about we all pick up one of these beauties for our hospitals before flu season kicks in? The Mold and Germ Destroying Air Purifier “eliminates up to 100% of airborne bacteria, mold, viruses, pet dander, dust mites, and pollen without making a sound or using a filter.” I guess the key is that “up to …” phrase. (Note to catalogue copy writers: doctors never use the word “germs” unless talking to non-medical people.)

For reference, today’s title was brought to you by the makers of the ABIM Recertification Exam, who truly have a thing for fish poisonings.

January 22nd, 2012

Generic Lamivudine Has Arrived

An e-mail from a patient last week:

Just got refills. Epivir is now generic??? Refill is simply labeled Lamivudine Tablets by Aurobindo Pharma USA, Inc …but made in India. Should I be concerned about that???

John

I told John (not his real name) not to be concerned — he is merely substituting the generic for the branded version, not switching from a fixed-dose combination or from a different drug (that drug being emtricitabine, or FTC).

With all the hoo-ha about generic atorvastatin, this one is much more under the radar. And the process to approval has not been smooth, as I wrote about here and here.

With all the hoo-ha about generic atorvastatin, this one is much more under the radar. And the process to approval has not been smooth, as I wrote about here and here.

But generic lamivudine for HIV treatment is a watershed moment nonetheless, since it’s really the first time there’s a generic antiretroviral that we might actually consider prescribing. (Zidovudine and didanosine have been generic for years.)

It will be fascinating to see how this plays out, both here in the US and in other developed countries.

January 21st, 2012

More Medical Testing! No, Less! You Decide

Fascinating Yin-Yang this week on the issue of medical testing. Want more? Want less?

First, this remarkable piece on retail medical labs, including a description of a company called ANY LAB TEST NOW:

Labs where folks can just walk in and order tests on themselves are popping up in retail centers across the country… At Any Lab Test Now, co-owner Anthony Richey pulls out a long sheet of paper with all the different tests his lab offers. There’s everything from an HIV screening to a “fatigue” panel. It looks like a sushi menu. “You say, ‘Well I want to check my diabetes, I want to get a hemoglobin A1C, and maybe I’ll check my lipid panel. And I’m a male over 40 so I’ll get my PSA checked,’ ” Richey says.

On the company’s web site, there are plenty of smiling, healthy people, plus these appealing claims: “No Doctor’s order needed … No appointment necessary … No insurance needed … Most results available in 24-48 hours.”

No doubt this is excellent customer service. But care to guess what that “Fatigue Panel” will set you back? That will be $499, thank you very much. But maybe they offer Gift Cards, that should help.

And if anything comes back abnormal?

If your results are ‘abnormal’ or ‘out-of-range’ from the normal, please contact your physician.

Joy.

It’s a poorly appreciated fact that the lower the likelihood of a disease being present, the greater the chance of a false-positive result.

Which is why no sensible physician would order all the components in the “Fatigue Panel” — which of course includes Lyme and EBV testing — without first taking a thorough history to determine if these diseases are even worth considering.

Meanwhile, over in the Annals of Internal Medicine, a group from the American College of Physicians this week argues for less testing:

The overuse of some screening and diagnostic tests is an important component of unnecessary health care costs… Efforts to control expenditures should focus not only on benefits, harms, and costs but on the value of diagnostic tests—meaning an assessment of whether a test provides health benefits that are worth its costs or harms.

What follows is an entirely sensible view of medical testing, with certain problematic, “low-value” tests called out for being wasteful — including the Lyme test mentioned in that “Fatigue Panel.”

And those false-positive tests, which retail labs must be generating by the crateload every day?

False-positive results are of concern because they often lead to further testing, which may be expensive and potentially harmful. They may also create anxiety for the patient and may lead to inappropriate treatment.

Which brings us back to the primary motivation of ANY LAB TEST NOW, which must be obvious by now:

“From a marketing standpoint it’s a good position to be in where you create a service, create a demand,” says Rodney Forsman, president of the Clinical Laboratory Management Association. “It becomes a consumable like Starbucks or bottled water.”

My advice? I strongly recommend that someone from ANY LAB TEST NOW contact the guys running GNC and explore co-franchising options.

They completely deserve each other.

January 18th, 2012

ID Case Conference Discussant Types

We specialists in Infectious Diseases love case conferences — especially those where the case is presented as an “unknown”, and we try to figure out the diagnosis from the history.

I suppose this isn’t very surprising, since ID cases in general are already among the most interesting in all of medicine. Those that are case-conference-worthy are particularly prime.

“Funny bug in a funny place,” was how one of my colleagues characterized these cases.

After the case is presented, the discussion by the participants takes various forms. I’ve been to hundreds of these conferences over the years, and have noted that the path taken by the discussants to arrive at the diagnosis (or not) varies quite a bit. There are certain styles, certain patterns of medical thinking in the conference room (rather than in the exam room or at the bedside) that show up again and again:

- The instinctual, “Here’s the diagnosis” approach. Very valuable when spoken by the Giants in the Field, who usually have several decades of clinical experience. These are short, targeted discussions that impressively even list the possible diagnoses in order of likelihood. Lou Weinstein was the quintessential “here’s the diagnosis” guy; sadly I only got to hear him discuss cases in the last few years of his distinguished career. Not surprisingly, this kind of medical reasoning doesn’t work nearly as well when attempted by relative beginners, e.g., a medical student, or even a second-year ID fellow. Bottom line: Beware the clinician in his/her 20s who begins a case discussion with the phrase, “In my clinical experience …”

- The comprehensive, “I’ve considered the entire universe of living organisms” approach. Can be both spectacularly interesting and educational or, conversely, crushingly, mind-numbingly boring. Mort Swartz (another Giant in the Field) discusses cases in this style, and I learn something from Mort every time — his knowledge not only of ID but all of Internal Medicine is awe-inspiring. However, my heart always sinks when a mere non-Mort mortal (couldn’t resist) starts a discussion by listing all the main categories of microorganisms as a prelude: “Let’s see, as potential causes for this person’s infected hip, there are prions, viruses, aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, higher bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, algae, protozoa, helminths, ectoparasites …” Time to get some more coffee.

- The prodding, “Let’s stop this game and tell me the diagnosis” approach. Usually goes something like this: A generic case is presented with minimal information — let’s say a man with a skin infection. No further history is given. And the discussant, not surprisingly, prods the presenter to give more information. “Any cats?” he/she asks, thinking Pasturella multocida or bartonella. “Any water exposure?” thinking Aeromonas hydrophila or Vibrio vulnificus. Because the discussant knows a simple skin infection is never going to make it to case conference, he/she keeps searching — there MUST be something interesting about the epidemiology. The presenter relents: “Well, as it turns out, the patient works as a clam shucker.” Bingo, Mycobacterium marinum or Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae.

- The diverting “I don’t know what this diagnosis is, but I certainly know a lot about other stuff, so let’s talk about that” approach. This clever strategy usually involves a true expert in a field forced out of his or her comfort zone. The world expert on salmonella, for example, suddenly finds him/herself discussing a hospital-acquired pneumonia in a patient who’s just had cardiac surgery. You can be sure that eventually the subject of intracellular pathogens (of which salmonella is an excellent example) will come up — somehow.

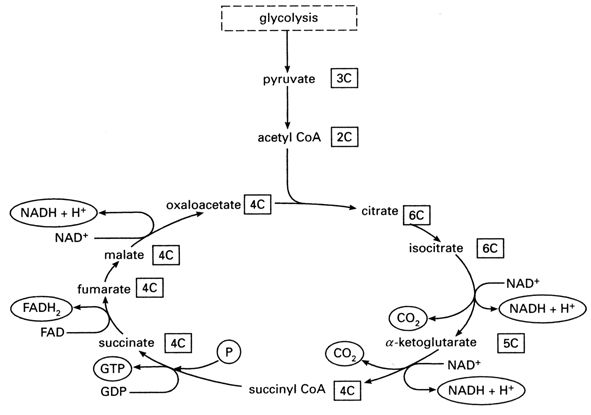

- The deer in a headlights, “You talking to me?” approach. Happens frequently when someone gets called on to discuss a case who’s not expecting it. Perhaps they’re junior faculty. Or just shy. Or maybe their mind has wandered, and they’re thinking about the Patriots’ playoff game, or whether to have another muffin, or the Krebs cycle. (I have never spontaneously thought about the Krebs cycle — see Figure above for a refresher.) And I’ve been informed by one of my most esteemed colleagues that some people just hate being called on, which I totally respect. (But others love yacking away during conference — they get offended if they’re not asked to opine — so it would be helpful to know how people feel about this. A green sticker on your white coat, perhaps, one that reads, “CALL ON ME!”) Suffice to say the startled discussant rarely gets the diagnosis correct, but they are often inadvertently funny.

Here’s a tip — if you’re ever asked about a case during conference, and you haven’t been listening, and the person being discussed is acutely ill, just say, “It could be staph.” If chronically ill, “It could be TB.” You will never be wrong.

What kind of discussant are you?

January 10th, 2012

First Rabies Case in State in Over 75 Years Raises Questions (Again) About Preventive Strategies

The recent case of bat-related rabies in a Barnstable man has prompted my colleague Larry Madoff, director of the Division of Epidemiology and Immunization at the Mass Department of Public Health, to write this fine commentary in the Atlantic.

I particularly like these passages:

Rabies is perhaps the archetypal zoonotic disease, one spread between animals and humans. It has an extremely broad host range, with the ability to infect all mammals. The ancients understood that when a mad dog bit another dog, it too became mad … While rabies is transmissible between any species, most transmission occurs within the species — bat to bat, raccoon to raccoon — and the virus adapts slightly to its host. That means each virus carries a signature in its genetic sequence indicating the species and geographic location of the “donor.”

He also states, “Keeping bats out of our homes, particularly our sleeping quarters, is a key public health measure in reducing human rabies.”

But as I’ve written before, I’m not so sure the numbers back this up as an effective preventive measure — or at least one we can quantify. Sure, we should try to keep bats out of our bedrooms, and I’d be quick to get immunized if one bit me.

But will these individual efforts — or the recommended practice of giving rabies immune globulin plus the vaccine series for “bats in the bedroom” exposures — actually reduce the number of rabies cases? Maybe not.

To recap the logic in this Canadian study:

- Bats in houses — incredibly common.

- People seeking preventive immunization with bats in the house — very rare (though some summer evenings I bet emergency room docs feel otherwise).

- Cases of bat-related rabies — EXTRAORDINARILY rare, often zero cases in a calendar year. The man from Barnstable was the fourth case in 2011 in the entire United States, the first rabies case in Massachusetts since 1935 — and first-ever bat-related case in the State.

Since most people with bats in the house aren’t seeking immunization, and since the “number needed to treat” to prevent a single case of rabies is estimated to be 2.7 million (!), the Canadians scrapped the recommendation that people who awaken to find a bat flying around their room get immunized.

And according to Larry, the World Health Organization now advocates a middle ground strategy of vaccine alone for minimal risk exposures. (US guidelines recommend rabies immune globulin as well.)

Time will tell whether these less aggressive approaches to rabies prevention will be the right move.

But I have a sneaking suspicion that sporadic cases will continue to occur — fortunately rarely — no matter what we do.

January 4th, 2012

How Does Herpes Treatment Trigger a Positive Test for Performance-Enhancing Drugs?

Here’s my guess on how many of this blog’s readers know the following “facts”:

Here’s my guess on how many of this blog’s readers know the following “facts”:

- Acyclovir and related drugs are used to treat herpes: nearly 100%

- Ryan Braun, superstar left fielder for the Milwaukee Brewers, is facing a 50 game suspension for testing positive for elevated levels of a “banned substance”, most likely testosterone: 10%

- Braun has disputed the results, stating that it’s a false-positive caused by treatment he’s receiving for a “private medical issue”: 1%

- That medical issue is widely rumored to be herpes: 0.01%

Now I should mention that I am a huge Ryan Braun fan, not only because of his stellar play, and his nickname (“The Hebrew Hammer”, one Braun shares with Hammerin’ Hank Greenberg), but also because he bears an uncanny resemblance to my nephew.

But it’s that last bullet point I can’t quite figure out — treatment of herpes is incredibly safe. How in the world would it lead to an elevated level of testosterone?

Turns out, it doesn’t.

But a quick search of “acyclovir” and “testosterone”, plus a perusal of an actual book — the irreplacable The Use of Antibiotics — finds that there are some obscure animal studies suggesting that anti-herpes drugs could do the reverse, i.e., lower testosterone levels.

From the book:

Dose-related testicular atrophy and abnormalities of spermatogenesis were noted in mice, rats and dogs treated on repeated occasions with either famciclovir or penciclovir …

All of which leads me to the very speculative conclusion that some doctors could be providing testosterone supplementation to their patients receiving anti-herpes therapy.

Which is, frankly, a completely bogus indication, way more “out there” as a practice than the typical off-label use of approved medications.

But that’s the only way I can connect the dots here.

In other words, something’s not right — the test result, the diagnosis, the prescribing practice — we just don’t know what that is yet.

January 3rd, 2012

Prevnar Now Approved for Adults — But Should We Start Using It?

From the FDA (and thanks to Physician’s First Watch for reporting the news):

Prevnar 13, a pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine, was approved today by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for people ages 50 years and older to prevent pneumonia and invasive disease caused by the bacterium, Streptococcus pneumoniae.

As shown in multiple studies, Prevnar has dramatically lowered the incidence of pneumococcal disease, both in immunized children and also non-immunized children and adults through “herd immunity.” The shift to infections with non-Prevnar covered serotypes has been of some concern, but clearly this vaccine has had a major beneficial effect — something harder to prove with the older, less immunogenic polysaccharide vaccine.

So should we use start using Prevnar in adults?

When I have difficult vaccination questions, I turn to several reliable sources:

- My wife — pediatricians must give 100X (or more) vaccines than adult doctors

- The Immunization Action Coalition, especially their “Ask the Experts” section

- Howard Heller, my friend, ID Colleague, and Chief of Medicine at MIT Health Services, and adult immunization clinical expert

Howard kindly responded to my query this morning, and here’s his take:

We should still use the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine (Pneumovax, PPS23) for adults until and unless the ACIP changes their recommendations. Although the conjugated vaccine induces higher antibody levels it has not yet been shown to decrease incidence of pneumonia, invasive disease or death. That study is underway. They will also be reviewing the data on the effect that Prevnar-13 in children has had on herd immunity and the prevalence of the various serotypes in invasive pneumococcal disease in adults. The advantage of the 23-valent vaccine is that it covers 10 serotypes that are not covered by PCV13. Stay tuned.

Thank you for that curbside, Howard — let me know if you have any questions about antiretroviral therapy!