An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

July 5th, 2012

Home HIV Test Big News — But Why? And What Impact Will It Have?

The recent FDA approval of a home HIV antibody test (OraQuick In-Home HIV Test) was covered just about everywhere. It’s an oral swab test, takes 20-40 minutes, and will be available over-the-counter.

The recent FDA approval of a home HIV antibody test (OraQuick In-Home HIV Test) was covered just about everywhere. It’s an oral swab test, takes 20-40 minutes, and will be available over-the-counter.

How big a news story was it?

- Several hundred sources featured it on the day of the announcement, and the total count is now well over a thousand

- It grabbed the coveted far-right column of the front page of the New York Times — not much HIV or ID-related information makes that spot these days

- It’s been picked up by numerous international media outlets; Canadian HIV specialists are calling for approval of the test in their country as well

- Naturally, our First Watch service made the story #1 today

Note that the coverage of the approval has been overwhelmingly favorable.

I’m glad that the approval has raised the importance of HIV testing in the public’s eye, but confess I was a bit surprised by just what a huge news story this has become. Furthermore, relatively few have questioned how useful this test will be. After all, another home HIV test was approved for use in 1996, and its impact has been limited.

(Some believe that this is because it’s relatively costly and is not really a true home test — it requires a fingerstick at home, then mailing the specimen into a central lab.)

It’s significant that something similar to this recently approved true home test was initially under review way back in 2005. Shortly thereafter, my inimitable colleagues Rochelle Walensky and David Paltiel published an opinion piece in the Annals of Internal Medicine entitled, “Rapid HIV Testing at Home: Does It Solve a Problem or Create One?”

The provocative title says it all: They argued that home testing, while helping to increase the number of tests and decrease stigma, would have a negligible effect on identifying more people with undiagnosed HIV infection — all while creating additional problems due to the inaccuracy of the test:

Home HIV testing will attract a predominantly affluent clientele, composed disproportionately of HIV-uninfected, “worried well” persons and very recently infected persons with undetectable disease [due to the window period before seroconversion]. This will have the perverse effect of increasing the proportion of false-positive and false-negative results, while making little appreciable dent in the size of the undetected HIV pool.

So hooray for the normalizing of the HIV test.

But whether the home test will actually do much to identify those at greatest risk remains to be seen.

June 29th, 2012

HIV Testing Roundup, and a Brief Rant

I’ve written so many times about HIV testing that a complete list of the headlines fills two full web pages.

But since the last entry on the topic was more than a month ago, one might think I’ve lost interest in the topic.

Never!

Three items on the HIV Testing radar, two national, one local.

First, for a classic good news/bad news report, read these latest data from CDC on previous HIV testing among newly diagnosed people with HIV in the United States. Among the highlights/lowlights:

- Good news: 60% of more than 50,000 newly diagnosed individuals reported having a previous negative test, many within the previous couple of years so that their HIV was diagnosed early.

- Prior negative testing was correlated with factors associated with access to care and high awareness of HIV risk: whites, individuals aged 13 to 29, and males reporting male-to-male sexual contact as their sole risk factor.

- Bad news: blacks, those aged ≥50, heterosexual contact as the sole risk factor, and males reporting injection-drug use were least likely to have a prior negative HIV test — and also far more likely to progress to AIDS at or shortly after diagnosis.

Second, could rapid HIV testing in pharmacies be part of the solution?

This sounds like a great initiative, as there is little doubt it’s easier for many people to go to their pharmacies than their health care providers. I’ll be particularly interested to see how this is implemented on a practical level, including feasibility, cost, acceptance rate, and most importantly, how people with positive tests get linked to care.

Third, we’re only about a month away from when it becomes legal in Massachusetts to obtain an HIV test without written informed consent — law signed in April, “official” July 31. (We’ll be the last state to drop the requirement, for the record.) It’s not an “opt out” policy — verbal consent is still required — but it’s substantial progress nonetheless.

All good, right? Not so fast.

The privacy part of the HIV testing law — which states that HIV testing results cannot be disclosed without a patient’s written consent — has not changed. Some (I hope a minority) have interpreted this to mean that written consent is still required before the test result can be reported by the lab — even if that means simply putting the result into the patient’s medical record (a record already protected by HIPAA). To quote/paraphrase an email forwarded to me from another institution:

… although the law now permits oral consent, we must still obtain written consent to share the test or results with any provider – meaning we still need written consent to include this information in the medical record.

It goes without saying — but I’ll say it anyway — that this bass ackwords interpretation obviously leaves us back where we were before the law changed. Thank goodness it’s not an interpretation shared by all institutions and practices.

And, for the record, it’s an intepretation that is utterly at odds with the intent of the change in the law, which was to expand HIV testing by removing written consent — so that people with this potentially fatal infection can access lifesaving treatment and stop spreading the virus to others.

So glad I didn’t go to law school. I’d spend hours a day with smoke coming out of my ears.

June 24th, 2012

ID Learning Unit — Choosing a Quinolone

We love quinolones on medical services, and it’s easy to understand why. Advantages:

We love quinolones on medical services, and it’s easy to understand why. Advantages:

- Ideal spectrum for several common infections, including community-acquired pneumonia, UTIs, and more complex infections when combined with other drugs

- Great oral absorption

- Few drug-drug interactions

- Once- or twice-daily dosing

- Generally well tolerated

- Reasonable cost

But how do you choose between them? Below, in a concise and admittedly somewhat oversimplified table, is all the medical intern/resident/hospitalist needs to know about our friends the quinolones:

| Drug | Activity vs gram – rods (rank) | Activity vs gram + cocci (rank) | Activity vs Anaerobes (rank) | Metabolism | Comments/Fun facts |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 | 3 | 3 | Kidney | Don’t use for Strep pneumo; no association with increased cardiac death in recent study (unlike levo, azithro) |

| Levofloxacin | 2 | 2 | 3 | Kidney | Active (left) enantomer of ofloxacin – hence its name. How cool is that? |

| Moxifloxacin | 3 | 1 | 1 | Liver | Not active vs. Pseudomonas; generally the preferred quinolone for mycobacterial infections |

But it’s not all sunshine and happiness with these drugs. Problems:

- That nasty tendon issue

- Can make people (especially the elderly) kind of crazy – “like 5 cups of Starbucks, and not in a good way”, was one patient’s memorable description

- Photosensitivity

- QT prolongation

- Oral absorption blocked by concomitant iron, magnesium, calcium, aluminum, and probably also Krugerrands if you happen to be eating them

- C diff risk, something we really didn’t see until the emergence of the more virulent strain

- Ever rising rates of resistance with gram negative rods, Staph aureus

Bottom line? These are great antibiotics – but they are not interchangeable, and not 100% safe.

Extra credit: Can you name the five quinolones that have been pulled by the FDA for safety reasons? Double points if you get the reason they are no longer available, triple points if you also get the brand names and match them to the actual drugs.

Here’s a hint to get you started.

June 18th, 2012

ID Learning Unit — Serologic Tests for Syphilis

Diagnosing syphilis is tricky for lots of reasons, including:

- The protean disease manifestations, many of which were best described in older medical literature — and hence not known to people who don’t read words on paper (vs a screen) very often.

- You can’t visualize the bug (Treponema pallidum), unless you happen to have a darkfield microscope nearby — which, if you’re like 99.99% of clinicians, you don’t have at all.

- You can’t culture the bug, unless you use a rabbit — and all I can say about the various techniques of xenodiagnosis is yuck.

- There is a seemingly endless list of available serologic tests, each having a potentially different purpose and all of them carrying an indecipherable acronym.

It’s this last one that is the topic of today’s ID Learning Unit. All you need to know (not everything you could know) about blood tests for syphilis.

There are the screening tests:

- Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR) — detects antibodies not to T pallidum, but to cardiolipin-cholesterol-lecithin antigens, which are present in active syphilis; which begs the question, what the heck is a “reagin”, and how do you pronounce it? Lots of false positives.

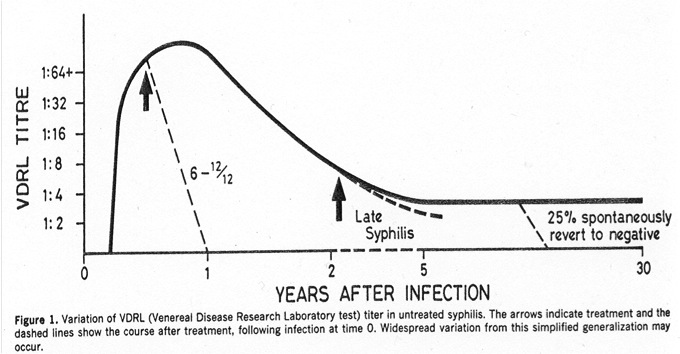

- Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) — detects antibodies to the same antigens, just a different technique, and seems to be used much less often; test of choice in the CSF, where it’s believed to be specific (but not sensitive) for neurosyphilis. Of course, how we know that is very mysterious, just like everything about neurosyphilis.

- Treponema pallidum enzyme immunoassay (TP-EIA) — the new kid on the block and, finally, a screening test that actually looks at specific treponemal antigens — hence more specific, fewer false positives. The TP-EIA is replacing the RPR and VDRL as a screening test in many high-volume settings (hospitals, STD clinics, etc); we switched to it at our hospital a few years ago.

Next, there are the confirmatory tests:

- Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS)

- Microhemagglutination test for antibodies to Treponema pallidum (MHA-TP)

- Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (TP-PA)

All positive screening tests must be confirmed with one of these confirmatory tests (our state lab does the TP-PA). It’s particularly important for the RPR and the VDRL because, as noted above, these tests measure antibodies to non-specific antigens and have lots of false positives. Hey, weren’t you listening?

And finally, we bring back a couple of the screening tests to measure disease activity:

And finally, we bring back a couple of the screening tests to measure disease activity:

- RPR (mostly)

- VDRL

Both of these rise shortly after the lesion of primary syphilis (the chancre), then peak during secondary syphilis. Treatment hastens their decline, but some people will spontaneously revert to negative even without treatment (see figure, which is from an ancient but excellent paper, Ann Intern Med 1986;104:368). Which is why the above screening tests (RPR and VDRL) may be unreliable in evaluation of that elderly patient with dementia, and why they don’t really measure disease activity for late manifestations of syphilis. So if you really think it might be neurosyphilis, you should order TP-EIA or one of the confirmatory tests, listed above.

Two small digressions about the RPR and VDRL. First, the units. When positive, these tests are reported in dilutions — e.g., 1:4 is a one-dilution lower (and a two-fold lower) titer than 1:8. Not many of our tests get reported this way (ANA comes to mind as another); in general, it’s only considered a significant change if it’s two dilutions or more — 1:16 goes down to 1:4 after treatment, for example.

Second, they may be falsely negative due to the “prozone” reaction, which does not refer to place to buy auto parts. The prozone reaction occurs when the the antigen and antibody bind together forming a complex, blocking the clumping that labs look for when doing an RPR or a VDRL. If labs are alerted to the possibility of a prozone effect, they can do dilutions to reveal the expected agglutination.

All very simple, right? Hey, it’s topics like this that keep ID doctors in business!

June 17th, 2012

For Inpatients, HIV Medication Errors Common — Then Promptly Corrected

Several papers have shown that antiretrovirals may be incorrectly prescribed for hospitalized patients with HIV. How do they do at Johns Hopkins — the site of one of the best comprehensive HIV programs in the country (and perennial US News and World Report #1 Hospital in the Universe)?

Several papers have shown that antiretrovirals may be incorrectly prescribed for hospitalized patients with HIV. How do they do at Johns Hopkins — the site of one of the best comprehensive HIV programs in the country (and perennial US News and World Report #1 Hospital in the Universe)?

As described in a new CID paper, investigators reviewed ART medication orders from all hospital admissions among HIV-infected patients in 2009 (702 admissions among 388 patients). In 380 admissions, ART was prescribed on the first day of hospitalization, and in 29% of these, a medication error occurred (145 total). By the second day of hospitalization, however, the error rate had dropped to 7%.

The most common errors were incomplete regimens (for example, prescribing only the PI component and leaving off the NRTIs), but incorrect doses, incorrect dosing frequency, and significant drug-drug interactions were also noted.

Not surprisingly, errors were more common with PI-based components, as these have a wider range of recommended doses, generally require ritonavir, and have more drug-drug interactions. (Plus, let’s face it it’s easier to get right single pill regimens — Atripla one PO QHS — than salvage regimens, pretty much all of which include boosted PIs.) There were significantly more errors on surgical services. The authors attribute the rapid correction of medication errors to their using clinical pharmacy review of medication orders.

These results are certainly consistent with our experience as well: Patients with HIV who require hospitalization often report that on the first day in the hospital, the regimens that they have been taking so meticulously are given incorrectly.

Since hospitalizations among HIV patients are steadily declining, and the vast majority of antiretrovirals are prescribed by a relatively small number of clinicians, we can’t expect hospitalists and medical housestaff to be familiar with these medications. Having them reviewed by a clinical specialist in HIV is critical — a practice we’ve adopted at our hospital as well.

June 15th, 2012

ID Learning Unit — The D Test

I suppose it’s not surprising that we’d follow-up the Etest with the D test, though perhaps if I were being alphabetical, the order would have been reversed.

The D test is important, because it screens for a form of clindamycin resistance in MRSA that might otherwise not be detected — the “inducible” kind, which can be associated with treatment failures. About half of MRSA isolates have this form of resistance.

The D test is important, because it screens for a form of clindamycin resistance in MRSA that might otherwise not be detected — the “inducible” kind, which can be associated with treatment failures. About half of MRSA isolates have this form of resistance.

Here’s how it works:

- Take some erythromycin-resistant, clindamycin-“sensitive” MRSA, spread it on a culture plate

- Drop an erythromycin disk on the left side of the plate, and a clindamycin disk on the right

- If there’s a flattening of the zone of inhibition between the two disks, then the test is positive, confirming inducible clindamycin resistance

- Report that bug as clindamycin resistant

First, critical thinkers will wonder why this is important, since we obviously don’t give erythromycin with clindamycin to an actual patient. My big-picture explanation is that it’s a marker for easily inducible resistance even without the erythro being present.

And second, note the critical step of putting the clindamycin disk on the right — otherwise the shape of the zone of inhibition won’t be a “D”, and everyone will be confused because who knows what to call that shape.

(That second part was a joke.)

June 13th, 2012

Questions About HIV Cure, and a Very Funny Quote

The single case of HIV cure following allogeneic bone marrow transplant is in the news again, this time because of data just presented at “The International Workshop on HIV and Hepatitis Virus Drug Resistance and Curative Strategies” (formerly known as the “HIV Resistance Workshop” — how’s that for rebranding?).

The single case of HIV cure following allogeneic bone marrow transplant is in the news again, this time because of data just presented at “The International Workshop on HIV and Hepatitis Virus Drug Resistance and Curative Strategies” (formerly known as the “HIV Resistance Workshop” — how’s that for rebranding?).

I’m not at the meeting, which is too bad since they often have it in splendid locations.

But from what I gather based on the report, here are the key findings in the study:

- The patient remains off antiretroviral therapy, with a normal CD4 cell count

- He has generously submitted multiple specimens for research analyses at multiple different time points

- Highly sensitive assays of various sorts have been performed at several labs

- HIV RNA has been detected in plasma in 2 (of 4) labs from 3 different time points; levels are lower than those typically seen in virologically suppressed patients on ART

- HIV DNA was detected in a rectal biopsy sample by one lab

- No HIV has been detected in CSF or peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- No replication-competent HIV has been isolated

My gut feeling is that the findings are potentially real, but unlikely to be of much clinical significance if virus can only be detected intermittently by special assays, especially since he’s been off all HIV treatment for more than 5 years.

But they may not be real — we need to remember that a false positive test result is more likely when the test’s sensitivity is cranked up and it’s performed multiple times.

Or as more colorfully put by Doug Richman:

If you do enough cycles of PCR, you can get a signal in water for pink elephants.

And if this interesting presentation tells us anything, it’s that defining success in any study of an HIV cure strategy is going to be very, very difficult.

June 12th, 2012

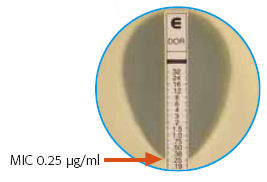

ID Learning Unit — The Etest

Every year I attend on the general medical service, so it gives me a chance to work directly with the medical residents — and to brush up on my non-ID-related Internal Medicine.

Every year I attend on the general medical service, so it gives me a chance to work directly with the medical residents — and to brush up on my non-ID-related Internal Medicine.

In exchange for what they teach me, each day on rounds I try to tell them about at least one ID-related thing that they may not know. Since I do this in the spring, they’re awfully sharp. Fortunately, I’ve been doing this ID stuff a long time, so can usually find something.

Today’s learning unit was the “Epsilometer Test, or “Etest” — that brilliantly simple way of estimating the MIC of an antibiotic to an organism, by using a drug-impregnated strip that has a gradient of concentration, from high to low. Find where the “elipse” of inhibition crosses the strip, and presto! There’s your MIC.

We take for granted that this method is readily available and, for the most part, clinically valid. It’s worth remembering, however, that when it debuted in the late 1980s/early 1990s, it was considered pretty slick and not entirely trustworthy.

And there’s still some debate about how reliable it is, especially with MRSA.

If you want to learn how to do it, watch this movie.