An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

October 28th, 2012

Dolutegravir and the 88% Rule

In the latest treatment-naive trials of elvitegravir and dolutegravir, there’s a striking consistency in the results of the “test” regimen. Here are the studies, with the percentage of responders by treatment arm:

In the latest treatment-naive trials of elvitegravir and dolutegravir, there’s a striking consistency in the results of the “test” regimen. Here are the studies, with the percentage of responders by treatment arm:

- Study 102: TDF/FTC/EFV (84%) vs. TDF/FTC/EVG/c (88%) — non-inferior

- Study 103: TDF/FTC + ATV/r (87%) vs. TDF/FTC/EVG/c (90%) — non-inferior

- SPRING-2: TDF/FTC or ABC/3TC + RAL (85%) vs. DTG (88%) — non-inferior

- SINGLE: TDF/FTC/EFV (81%) vs. ABC/3TC + DTG (88%) — ABC/3TC + DTG — superior

The last of these, the SINGLE study, is the only one where there’s superiority in the primary outcome for the experimental arm, here ABC/3TC + dolutegravir. As the lead investigator Sharon Walmsley note, this favorable result was largely due to a significantly higher proportion of subjects in the TDF/FTC/EFV group discontinuing therapy for adverse events (10% vs 2%), as rates of virologic failure were similar between arms. ABC/3TC + dolutegravir also was better than TDF/FTC/EFV from both the immunologic and resistance perspective.

And though cross study comparisons are frowned upon by purists, we can’t resist. Just a quick glance at all four of the EVG and DTG arms, and you can easily see that an 88% response rate is the new price of admission for any treatment-naive regimen.

Anything shy of the high 80s, and there has to be something else very special about the treatment — for example, better tolerability, much lower cost, better long-term safety, it helps you become a virtuoso violinist — to make it compete with options for therapy we already have, or will have soon.

October 17th, 2012

It’s Time to Tell Our Patients to Stop Their Vitamin Supplements

Over in JAMA, there’s a large study out today that (yet again) failed to demonstrate a benefit of vitamins.

Over in JAMA, there’s a large study out today that (yet again) failed to demonstrate a benefit of vitamins.

Over 3000 patients with HIV in Tanzania were randomized to receive either high-dose or standard-dose multivitamin supplementation, in addition to “HAART” (ugh). Though the study was planned for 24 months, it was stopped early by the Data Safety and Monitoring Board due to a higher rate of LFT abnormalities in the high-dose vitamin group. Not only that, the sickest patients — those with BMI < 16 — seemed to do even worse on the mega-dose, with a higher risk of death that almost reached statistical significance (relative risk 1.36; 95% CI, 0.93-1.98; p=.11).

One could quibble with the generalizability of the results to current standard of care in well-resourced areas — for example, the most common regimen was d4T, 3TC, and nevirapine, used in nearly 60% — but it’s hard to imagine how this makes the results less convincing. After all, one would expect that vitamin supplementation would be more important in settings where malnutrition and advanced HIV disease are highly prevalent.

So what should we do?

I’ve been keeping quiet with my patients who insist on taking handfuls of vitamins, despite their having access to real food and nothing at all to suggest dietary insufficiency. With this study, however, I will strongly encourage them to save their money — the only people benefiting from their daily intake are those in the $27-billion dollar/year vitamin industry.

October 16th, 2012

Some Liver Meeting “Wow!” Studies Start to Emerge

The Liver Meeting, the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, does not take place until November 9-13, in Boston.

The Liver Meeting, the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, does not take place until November 9-13, in Boston.

But if you want a preview, a couple of notable studies have already been “announced” in the press.

Specifically, there’s

Abbott today announced initial results from “Aviator,” a phase 2b study of its interferon-free, investigational regimen for the treatment of hepatitis C (HCV). Initial results show sustained virological response at 12 weeks post treatment (SVR12) in 99 percent of treatment-naïve (n=77) and 93 percent of null responders (n=41) for genotype 1 (GT1) HCV patients taking a combination of ABT-450/r, ABT-267, ABT-333 and ribavirin for 12 weeks, based on an observed data analysis.

That regimen contains 5 drugs — HIV/ID docs will recognize the “/r” as familiar short hand for ritonavir boosting — but it’s hard to beat those response numbers. Note especially the 93% cure rate in interferon null responders — amazing.

If 5 drugs seems like too many, there’s also this:

[Bristol-Myers Squibb] said 94 percent of patients who took a combination of three experimental drugs, daclatasvir, asunaprevir, and BMS-791325, were cured in a 12-week study. Those patients did not take interferon or ribavirin.

Looks like it’s going to be an interesting meeting. That sentence may be the understatement of the year.

October 15th, 2012

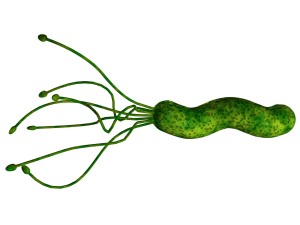

ID Doctors are Clueless about Treating Helicobacter

Every so often, we’ll get a referral from a gastroenterologist about a refractory case of Helicobacter pylori.

Every so often, we’ll get a referral from a gastroenterologist about a refractory case of Helicobacter pylori.

Usually the patient has been treated multiple times, and still has symptoms and a positive test. Naturally a referral to a specialist in Infectious Diseases seems warranted.

But the reality is that this is like the IV nurse contacting the July intern with a tricky IV, telling the newly minted doc that since he/she (the nurse) can’t get the IV in, the intern should give it a try.

Ha.

Because the fact is that most ID doctors know little if anything about treating helicobacter, which is overwhelmingly diagnosed and managed by primary care doctors and gastroenterologists.

The ID doc can read the guidelines as well as the next guy, but we have little hands-on experience with treatment. So choosing between the multiple different regimens, selecting the right PPI and dose, giving the right length of therapy, and deciding whether to use bismuth are practical skills we most definitely lack. Suffice to say it’s no accident that this study was covered in Journal Watch Gastro rather than Journal Watch ID.

I was reminded of this gap in our knowledge the other day with this exchange with one of my colleagues:

GI doc: Hey Paul, I have a question about Helicobacter treatment.

Me: OK …

[I’m worried. Should I tell him he might as well be asking his office receptionist?]

GI doc: I saw your patient John Smith, he’s on HIV treatment with blank, blank, and blank.

[He horribly mangles the regimen, which is tenofovir/FTC and boosted darunavir. I’m feeling better already.]

Here’s my question — what can I give him that won’t interact?

Me: Just avoid clarithromycin — it interacts with the darunavir and ritonavir.

[Amazingly, he’s asked me about the only thing I could possibly answer about helicobacter without looking it up.]

GI doc: Fine, I’ll use Pylera.

[I have absolutely no idea what that is. Time to come clean.]

Me: I have absolutely no idea what that is.

For the record, Pylera is a combination of bismuth, tetracycline, and metronidazole. Learn something new every day.

It’s pretty easy to understand why we know next to nothing about helicobacter — the disease used to require an endoscopy and biopsy for diagnosis. Regardless, it’s quite humbling to acknowledge that yes, there’s this fascinating (and very cool looking) bacterial infection out there about which most ID doctors have little if any expertise.

Perhaps that will change as rates of antibiotic resistance rise, especially if complex culturing and susceptibility testing are required. We’re really good at that stuff.

October 13th, 2012

More Questions from “ID in Primary Care” Course

Some additional excellent questions from the course:

Some additional excellent questions from the course:

- For someone who has had 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine but does not have the antibody, should we just go ahead and give another 3 shots?

A: (Per vaccine guru Howard Heller): The guidelines say to just go ahead and give another 3 shots but if the initial series was many years before then I usually give one booster dose and recheck antibody level 2 weeks later. If there is a robust response then I stop. And always consider the possibility of and screen for chronic infection as a possible reason for why the patient did not “respond” to the first series of shots. - If someone has a history of receiving 2 doses of MMR but they do not have antibodies, do you just give them one dose of MMR or 2 doses?

A: If they have documentation of the 2 previous doses or if their history is very reliable, then one dose. If there is any doubt about the reliability, then give 2. - My patient had a positive HIV ELISA, and an indeterminate Western blot. What should I do next?

A: As I wrote here, you must exclude acute HIV infection with an HIV RNA (viral load). And if that’s negative, it also would make sense to exclude HIV-2 with a differentiation assay. If both are negative, then it’s a false positive ELISA. Would repeat again in a month just to make sure. - How long is a person contagious with shingles?

A: When the lesions are crusted over, there’s no further viral replication and the person is no longer contagious. - Can a person get mononucleosis twice?

A: They can only get EBV-related mononucleosis once, but other infections that can mimic acute EBV mono include CMV, toxoplasmosis, and HIV. - Why do people think you look like Paul Farmer? You have a much stronger resemblance to Steve Buscemi.

A: Umm … Thank you… or not? (Above image with permission of www.mattleese.com.) Just in time for Halloween!

October 11th, 2012

Back to School: Questions at the “ID in Primary Care” Course

We do a post-graduate course each year called “ID in Primary Care,” and it’s a great way for us to find out what people in outpatient primary care practice are thinking about from the ID perspective.

I told the participants this year I’d post some of their most interesting questions on this site, with the hope that if we didn’t know the answer, perhaps some of you out there would.

Here’s a half-dozen from today:

- Since we need to use trimethoprim-sulfa for MRSA now, should we stop using it for UTIs?

A: The rate of MRSA-resistance to TMP-SMX among community isolates in the USA remains fairly low. It seems unlikely that the short course we use for UTIs would change this much. In my experience, most of the patients I’ve cared for who have a TMP-SMX-resistant MRSA have been receiving it chronically, usually for prevention of PCP. - Are there established risk factors for tendonitis on quinolones?

A: Older age, obesity, gout, and receipt of corticosteroids are reported risk factors for tendon disorders in this study; age and steroid use also came up in this one. Anecdotally, I’ve seen it in people younger than 60 and not on steroids, so clearly it can happen to anyone, risk factors aside. - Should we use clindamycin empirically for treatment of MRSA?

A: Aside from the obvious recommendation for I and D as critical to treatment of extensive soft tissue infection due to MRSA, we really have very little data on the optimal outpatient antibiotic to use for MRSA — or whether they are needed at all. That said, rates of resistance to clindamycin (either complete resistance or D-test positive resistance) are higher than to TMP-SMX or doxycycline. So personally I prefer not using clindamycin unless necessary, a view further reinforced by the elevated C diff risk with that drug. - Should the zoster vaccine be given to someone who’s already had zoster?

A: The short answer is yes — based on both guidelines and the fact that these are the most motivated patients to get the vaccine. But we should remember that the pivotal clinical trial establishing the efficacy of the vaccine excluded people with prior zoster, so it’s not known if it adds additional protection to the “auto-immunization” of an actual bout of shingles. - Any commonly used drugs for UTIs interfere with oral contraceptives?

A: Nope. But watch out for rifampin, which interacts with practically everything under the sun. - If someone has been coughing for more than a year (!), with no fevers and a negative chest X-ray, should they still be worked up for pertussis?

A: Though pertussis in adults is famous for causing prolonged cough, it’s hard to imagine that after 12 months making this diagnosis — even if you could — would 1) lead to a treatment that has any effect or, 2) prompt an intervention that reduces contagiousness. So I’ll go out on a limb and say forget about it.

Another batch coming soon.

October 8th, 2012

With One Month To Go, Candidates Eke Out Votes Wherever They Can

From the Department of Opportunistic Expediency, we have this brazen pitch from one of our two presidential hopefuls:

Romney and Ryan will do more to fight the spread of Lyme Disease … As president, Mitt Romney will ensure that real action is taken to get control of this epidemic that is wreaking havoc on Northern Virginia.

Suffice to say this bit of “microtargeting” — note I did not write “microbe targeting” — has various political motives, nicely outlined here and here and here.

But politics aside, the fact remains that we don’t have much data on the optimal approach to persistent symptoms after treatment for Lyme disease. It remains a very tough problem.

So if this silliness (or similar) can generate funding for some new legitimate research on the problem — free of politics and rancor and paranoia, and focused instead on trying to find strategies that actually help people — I’m all for it.

October 2nd, 2012

The Drug-Resistant Gonorrhea: How Much of a Threat?

By now, all ID docs know about the ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Or, more accurately, we’ve read about it, since the vast majority of gonorrhea cases are treated in emergency rooms, STI clinics, college health facilities, and various primary care settings — not places that most ID doctors typically work.

By now, all ID docs know about the ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Or, more accurately, we’ve read about it, since the vast majority of gonorrhea cases are treated in emergency rooms, STI clinics, college health facilities, and various primary care settings — not places that most ID doctors typically work.

Plus, hardly anyone does susceptibility testing or even cultures for gonorrhea anymore, so this “superbug” is quite different from the nasty ICU gram-negative rods or MRSA, which are diagnosed on a daily basis. We know the resistant GC is out there, but it’s kind of like carbon monoxide poisoning — if it’s causing problems, we probably wouldn’t know about it until too late.

All this made me quite interested to read two diametrically opposed perspectives on this latest resistant threat, both from accomplished physician-writers.

Over in the New Yorker, we have Jerry Groopman’s take. A hematologist-0ncologist at Beth Israel Deaconess, Groopman is known in the ID world as one of the pioneers of HIV care and research in early days of the epidemic.

In a piece entitled “Sex and the Superbug,” he takes the view that this drug-resistant gonorrhea is basically the product of 1) our overuse of antibiotics (natch) and, more importantly, 2) our enthusiasm for oral sex, which may not be as “safe” as commonly viewed. Let the “sexually active (or not)” be warned!

By contrast, Kent Sepkowitz, an ID doctor from Memorial Sloan-Kettering, wrote in Slate that all this attention paid to drug-resistant gonorrhea is just a lot of scare-mongering:

But I have to ask, people, why all the excitement? As a looming public-health calamity for John Q Citizen as he walks down Maple Street in Middletown USA, the threat is minuscule (particularly if John Q can remember to keep his pecker in his pants). As with the avian flu massacre that never was and the smallpox pandemic that never came, this Superbug fascination seems to be more about our peculiar love of fear itself (cf: Stephen King, Paranormal Activity, the Republican debates) than any sober consideration of the risk before us.

Both these pieces are quite entertaining and highly recommended. Don’t miss Groopman’s description of historical treatments for GC — yikes — and Sepkowitz is flat out irreverent (and funny!) in a way one rarely encounters in doctor prose.

In the meantime, I can only imagine how terrifying it would be to learn about this drug-resistant bug in high school health class — you know, that day when they “educate” teenagers about the perils of unprotected sex, with the mandatory grisly images.

Health teacher: “OK kids, now here’s one where we basically have no effective treatment.”

Class (all together): “Ewwwwww!!!”

September 24th, 2012

Quick Question: An Etiquette Column for ID Specialists

(First in what will undoubtedly be a recurring series.)

Hi Paul:

What do you do when someone in a non-medical setting gets something really wrong, and it’s in our field? Here’s why I’m asking: I was picking up my 9-year-old son from school the other day, and his teacher reported to me that they were worried one of the other students “had gastroenteritis” — he was sent home with diarrhea — but that they were reassured when they called his mother, who said it was “just food poisoning” so everyone at the school was relieved. I felt like telling her that basically these were the same thing, with the same implications for the other students, but I didn’t want to come across as a know-it-all, so I said nothing.

Your advice?

Bugged in Billerica

Dear Bugged,

I completely understand your dilemma. How many times have we (omniscient) ID doctors sat quietly with our friends, as they tell us things like “I’m sure this rare hamburger is safe since the meat came from [insert high-end food emporium here]”, or “I won’t get sick traveling to India since I’m staying only in business hotels,” or “I thought this cough was just a virus, but then it was actually bronchitis.” In your case, it’s the “Food poisoning ≠ infectious risk, so no worries.”

Wrong, wrong, wrong, and wrong. But how dreary our company would be if we were constantly lecturing people on the facts. So how should we proceed?

My approach is to intervene — gently — only when someone’s misconception is potentially harming them or others. Here’s some practice language for our examples:

- Rare hamburger: “I agree Whole Foods [oops, mentioned it] has great meat, but I’m pretty sure even they recommend cooking hamburgers thoroughly.”

- India trip: “One of my ID colleagues travels a ton for his research, and he says India can be tricky.”

- Virus/bronchitis: “I hope you feel better soon.”

So what should you have done at your kid’s school? It depends on the setting. If you had the time, saying something like, “Well, you know good handwashing always makes sense, maybe this illness can be a reminder,” possibly prefacing this comment (if you’re feeling didactic) with, “Food poisoning and gastroenteritis can be the same thing.”

But what you really want to avoid doing is creating false alarm — so asking the teacher to quarantine the sick kid when he returns and to start collecting stool samples from all the other 4th graders would be way out of bounds.