An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

June 15th, 2014

Poll: Should ID Doctors Still Do HIV Primary Care?

My friend and colleague Ken Freedberg is giving a talk soon at our regional IDSA meeting called, “Who Should Be Providing HIV Care?”

My friend and colleague Ken Freedberg is giving a talk soon at our regional IDSA meeting called, “Who Should Be Providing HIV Care?”

He’s a very smart guy (except during the football playoffs, when he is possessed by evil forces), so maybe he’ll answer this question that has strangely bedeviled our field for decades. But I’m sure his talk will be interesting even if he can’t solve the problem.

To recap a little history, jammed into this tiny paragraph: In the early days of the epidemic, some (but importantly not all) ID specialists didn’t want much to do with this highly charged, rapidly fatal disease of young and often stigmatized people. In response, other specialists and non-specialists got involved, forming the mixed blob of “HIV specialists” that we recognize today — a group of ID doctors, sure, but also internists, family practitioners, other medical subspecialists, nurse practitioners, PAs, etc.

Periodically, people with opinions on these sorts of things have weighed in on who provides the best care to those with HIV, or a slightly different take on the question, who should actually be doing it — especially the primary care part. A consensus has emerged that someone with experience and interest in HIV should be that person, regardless of training.

But even though the question has remained the same, the context has completely changed. Thinking back to when I saw my first outpatient with HIV in 1987, I can define roughly 4 eras:

- 1987-1995: Prevention, diagnosis, and management of opportunistic infections. Palliative and hospice care. Lots of putting out fires, putting fingers in leaky dikes, and rearranging desk chairs on the Titanic. (How’s that for battling metaphors). Plenty of tragedy, with accompanying intense family meetings.

- 1996-2000: Combination therapy arrives, with highly complex and toxic regimens using early generation PIs and NRTIs: ZDV, ddC, soft-gel saquinavir anyone? (That’s 27 pills/day, for those counting at home.) How much water should you drink each day to prevent indinavir-related kidney stones? Any downside to daily Imodium or Lomotil use? Can anyone really chew a full dose of ddI?

- 2001-2005: A growing awareness of the long term toxicity of certain HIV therapies. The “when to start” debate. Treatment interruptions of various flavors. Lots of resistance testing for treatment-experienced patients, many of whom were perfectly adherent but had no active drugs. Crazy salvage regimens that included “double-boosted PIs” and “mega-HAART” (ugh).

- 2006-today: More and more (and MORE!) patients every year on suppressive therapy. Clinical visits focus on prevention and screening, mostly targeting “non-communicable” comorbidities — heart disease, cancer, bone health, etc. If HIV therapy is discussed, it involves consideration of switching to simpler regimens, or whether HIV can be cured. (Can sometimes do the former; not the latter.)

During eras #’s 1-3, and the first few years of era #4, most ID doctors with HIV interest were ideally suited to doing HIV primary care. We loved this stuff, and each step forward was more and more rewarding — thrilling, even. Plus there were papers — actual data — showing that the more experience you had, the better the outcome for your patient. This paper was the most widely cited, back in Era #1. The lead author was (and is) a primary care internist, but the message resonated with ID specialists, who in many healthcare systems did the most HIV care.

Generalists, meanwhile, became progressively estranged from HIV as the eras progressed. There was a seemingly endless parade of new agents, the codes and complexities of resistance testing were befuddling, and the mile-long list of drug-drug interactions loomed ominously. I remember one (excellent) internist telling me that he got about as much out of reading an HIV resistance report as he did interpreting an EEG.

But how about today? An ambulatory practice once dominated by crisis management is now a comparably calm state of affairs, at least medically — the vast majority of people receiving care are virologically suppressed, and have been for some time. If 80% or so of patients in HIV care are stable, we can legitimately ask the provocative question — does it make sense that ID doctors still act as their primary care providers? Shouldn’t we move to the oncology model, where the specialists guide decisions about cancer treatments and complications, then the long term non-oncology follow-up of stable patients is done largely by generalists? Furthermore, aren’t generalists better at screening and prevention for non-ID issues than ID docs, who don’t focus on general medicine during their subspecialty training?

Or to take the other side: Shouldn’t ID doctors keep doing HIV primary care, since we have a nuanced view of HIV disease that didn’t come easy. The authors of these primary care guidelines, for example, are mostly ID docs. Example of “nuanced view”: We know we can largely ignore the atorvastatin-boosted PI drug drug interaction (just start with a low dose), but the fluticasone-boosted PI one can be a real nightmare. And wouldn’t our patients we’ve followed all these years wonder why we were dropping them from our primary care?

Since I’m not sure of the answer here, please take the following poll — and feel free to note your further thoughts in the Comments section.

June 4th, 2014

Anti-Vaccine Movement Slammed By Daily Show; ID Doctors, Pediatricians Happy

The anti-vaccine crowd gets a pretty good drubbing here from Samantha Bee on The Daily Show. I’d feel a tiny bit bad for them — gosh their opinions are pathetic — but since I’m an ID specialist married to a pediatrician, I can only rejoice in the brilliance of this piece.

And yes, stupidity crosses political party lines.

Enjoy!

Hat tip to Joel Gallant for the link.

May 28th, 2014

Some ID Stuff We’re Talking About on Rounds

Just finished two weeks on the inpatient general medical service — hence the radio silence — giving me a chance to work with residents, interns, and medical students. Here’s a smattering of the ID topics we discussed, along with a comment or two:

Just finished two weeks on the inpatient general medical service — hence the radio silence — giving me a chance to work with residents, interns, and medical students. Here’s a smattering of the ID topics we discussed, along with a comment or two:

- “Common” causes of gram negative soft tissue infection (at least for board exam purposes), and their associations: Pasturella multocida (cat bites), Vibrio vulnificus (salt water, especially in warmer climates), Aeromonas hydrophila (fresh water and leeches). Yes, leeches, which do have some legitimate medical indications. Our patient had Enterobacter cloacae (not leech-related), which led to a discussion about …

- “Inducible” AmpC beta lactamases, which get expressed after in vivo exposure to cephalosporins or expanded-spectrum penicillins. These are really tricky since the microbiology lab will report enterobacter spp. as sensitive to these antibiotics unless another resistance mechanism is present. So should all patients with serious infections due to enterobacter receive a carbapenem? Probably a good idea.

- Parasites are thought frequently to cause eosinophilia, but protozoan (single cell) parasites rarely do — except for the uncommon bugs Isospora belli, Dientamoeba fragilis, and Cyclospora cayetanensis. So if your patient has parasite-related eosinophilia, think worms — strongyloides, schistosomiasis, filariasis, etc.

- Is obsessive tweaking of vancomycin levels useful if you’re not treating confirmed Staph aureus and the patient’s renal function is normal? Highly doubtful. The drive to get vancomycin troughs between 15-20 is the ID-fellow equivalent for repleting potassium — a constant annoyance, and not always necessary.

- Watch out for ritonavir-related drug-interactions — in particular with inhaled or injectable corticosteroids. Some EHR interaction alerts should not be ignored!

- Still confused about the diagnostic approach to C diff? Here’s a very nice summary of what most micro labs are doing.

- Hemolytic anemia occurring weeks to months after surgery should prompt consideration of transfusion-related babesiosis. Cases may be seen year-round (but most in the summer) and throughout the USA. Median age 65. Median time to onset of symptoms around 50 days. And no, there is currently no routine screening of blood donors — but as soon as there is a reliable screening test, suspect there will be.

- One important cause of potentially severe hepatitis is herpes simplex virus, which can occur in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent hosts — in the latter, pregnant women seem particularly susceptible. Diagnostic test of choice is blood PCR for HSV DNA.

- The days of Western blot used to confirm HIV diagnosis are numbered, as we head towards this new algorithm. I note that one large commercial lab has already stopped sending the Western blot in favor of the HIV-1/2 differentiation assay — progress!

Rapid fire round: If culture results say “suspected enteric gram negative rods,” it will not be pseudomonas; ditto GNR that grow in both aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottles (true most of the time) … with disk diffusion susceptibility testing, large numbers indicate greater sensitivity (zone of inhibition), but with MICs, it’s a low number you want … a nice adaptation of the disk diffusion method is the Etest … sending sputum cultures gram stains and cultures on patients with pneumonia after they have been started on antibiotics is all but useless (does not apply to ICU intubated patients) … no one really knows the optimal management of persistent MRSA bacteremia … hepatitis B serologies are an endless source of diagnostic confusion for legions of medical students (and some house staff), so here’s a nifty chart … as we head into summer here in New England, the “doxy deficiency” work-up for febrile adults in the outpatient setting (without an obvious other source) consists of Lyme antibody, anaplasma (not ehrlichia) PCR, and babesia PCR … an organism that is resistant to ceftazidime but sensitive to cefoxitin or cefotetan will be an extended spectrum beta lactamase producer …

Finally, an observation that several commonly used drugs share the fate of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, meaning they may eternally be referred to on rounds by their brand names even though they are all off patent, some for many years. The leaders are:

- Hydromorphone (Dilaudid)

- Levetiracetam (Keppra)

- Furosemide (Lasix)

- Piperacillin-tazobactam (Zosyn)

Ready for 2’45” of fun? Off we go:

May 15th, 2014

CDC Recommends Broader Use of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis — Can We Make It Happen?

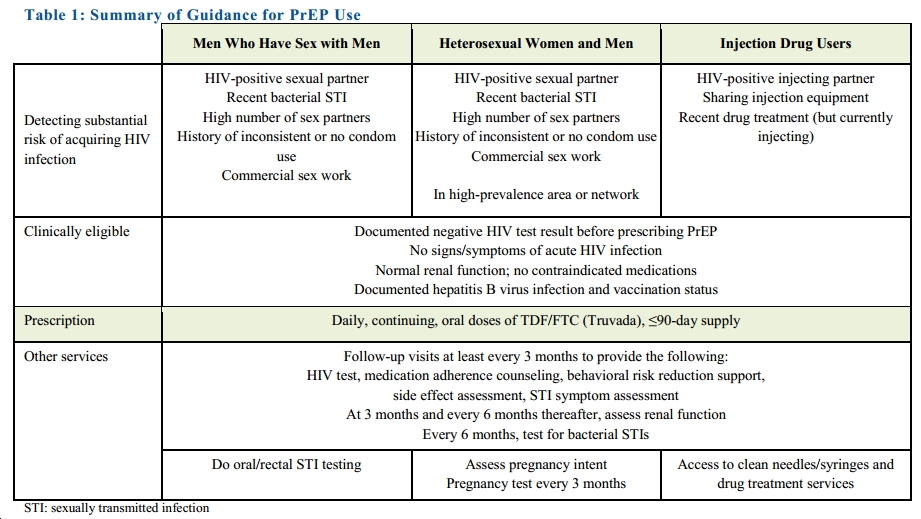

Making a much stronger and more comprehensive statement than their earlier “Guidance,” the CDC is now recommending tenofovir/FTC (Truvada) for all Americans at high risk for HIV. More specifically, they recommend it for a broad range of people who have certain risk factors (click to see full size image):

One certainly gets why this was done — as summarized nicely in this Times piece, it’s easy to be “frustrated that the number of H.I.V. infections in the United States has barely changed in a decade, stubbornly holding at 50,000 a year, despite 30 years of official advice to rely on condoms to block transmission.”

Plus, we know that PrEP really does work, provided people take it. An encouraging report from CROI this year found that adherence was nearly 80% among MSM seeking PrEP in three U.S. cities (Miami; Washington, DC; San Francisco).

And I have been surprised that we haven’t yet seen much of a decline in HIV incidence, even with a broader number of our patients in care receiving suppressive antiretroviral therapy, which essentially eliminates the risk of transmission to others.

However, it’s clear that the epidemic is being sustained by those not in care, which is why PrEP is so important. It also raises the first of several major challenges for clinicians, as the highest rate of HIV in the USA right now is in a population that tends not to access care on a regular basis — young, African-American MSM.

Other challenges:

- The risk assessment will have to be done on the front lines of care — that is, by primary care clinicians — as HIV-negative, at-risk patients do not see HIV/ID specialists.

- These PCPs will have to get comfortable prescribing tenofovir/FTC. It’s not that it’s complicated (“take one pill daily”), it’s just that it’s not a medication they currently use.

- They will also be responsible for monitoring both adverse events and (very importantly), incident HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

Because of these issues, in the few years since PrEP became an option for HIV prevention, we’ve been offering our PCPs a one-time ID consult to discuss the risks and benefits, with a strategy for further follow-up outlined for the primary provider.

So can PrEP be more broadly adopted? I think we (meaning the patchwork U.S. healthcare system) can pull this off.

But it won’t be easy.

May 3rd, 2014

The Top Items from the Revised DHHS HIV Treatment Guidelines

A sparkling, shiny new revision of the DHHS HIV Treatment Guidelines was released this week (thanks Alice Pau!), and provides plenty to read and think about — 285 pages, if you’re counting.

A few ways to navigate this gargantuan effort more efficiently — the What’s New section, the recommendations summarized here, and the tables here.

But if you want the Monarch Notes/CliffsNotes version (clearly an analogy soon to be as outdated as dial phones, fax modems, and 8-track tapes), here’s one perspective (mine, not the panel’s) on the most important changes:

- After two years of virologic suppression, frequency of CD4 monitoring reduced — and for those with CD4 > 500, it’s now “optional.” Everyone knows it makes no sense to modify treatment based on CD4 results alone in their patients on suppressive therapy, so it’s liberating to have this now formalized in treatment guidelines. Soon quality improvement programs, ADAPs, and others (patients?) will stop nagging us for CD4s in these situations. By the way, “optional” means “if it makes you and/or your patient feel better to check it, go ahead and do so.” It doesn’t mean that there are new guidelines for what to do with the results when the CD4 comes back 840, or 570, or 750, or 1001. And that’s because you should do nothing.

- More recommended initial regimens! As per the late 2013 update, there are now seven recommended regimens — the “core four” from 2009 (TDF/FTC + EFV, or ATV/r, or DRV/r, or RAL), plus the three other integrase options: TDF/FTC + EVG/c or DTG, and ABC/3TC + DTG. And now there’s an entirely new category for those with HIV RNA < 100,000, CD4 > 200, which for me predominantly exists for TDF/FTC/RPV. (ABC/3TC + EFV and ATV/r are also in there.) In fact, there are so many recommended regimens that the “preferred” term has been dropped, the alternative options relatively few in number (4), and many drugs (ZDV, FPV, MVC, SQV, NVP) no longer recommended at all. Makes sense to retire them, right? Why would you ever choose one of these for initial therapy in 2014?

- The “Regimen Simplification” section is now called, “Regimen Switching in the Setting of Viral Suppression.” That’s a much better title, and not only that, the entire section has been extensively revised. If you read the PDF versus the HTML version and are looking for the yellow highlighting showing what has changed in this section, it’s intentionally left out when so much is altered — too distracting.

- A whole new section on cost considerations. Gingerly treading into these potentially contentious waters, the section mentions cost sharing, prior authorizations, generic ART, lab testing (again), and the wholesale prices of various ART components.

Plenty more in there, of course. Now get reading!

April 27th, 2014

Why ID/HIV Specialists Rank Last in MD Salaries

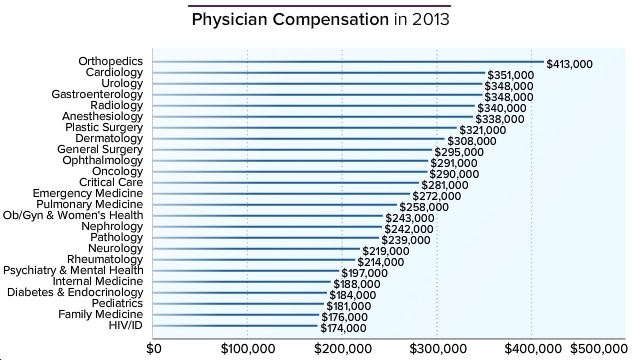

Here’s a figure from Medscape listing 2013 physician compensation:

Now a median of $174,000/year is hardly chump change, so I don’t expect much in the way of sympathy on these data. On the other hand, someone has to to be last, and note that our income hasn’t increased a bit since the last time I commented on this survey three years ago.

So it’s worth taking a few moments listing the top reasons why we rank so low, most of them probably as obvious to you as the antibiotic of choice for treatment of syphilis. Then we’ll once again end on a happier note.

Reason #1: Doctors in the USA are paid the most for doing procedures. A famous ID doctor once said, “No one ever got rich from doing a gram stain.” And even though I just made that quote up, it’s definitely true. We ID doctors barely do any procedures, and the few we can do are comparatively low ticket items such as PAP smears, CSF exams, minor wound care, I and D, etc.

Some ID/HIV specialists have added various procedures to their practice to offset this deficit, such as screening for anal dysplasia in their HIV positive patients using high resolution anoscopy, doing fecal microbiota transplants for C diff, or providing injections of facial fillers for lipoatrophy — that last one most certainly a cash business. However, these enterprising (and for the first two, strong-stomached) ID docs are the exception, not the rule.

Reason #2: Productivity of doctors is still measured in volume. In a fee-for-service, count-the-RVUs system, the more patients you see the more you get paid. And I suspect there are few patients less amenable to high volume service than those referred to ID/HIV doctors.

Consider these: Fever of unknown origin (clinic or hospital/ICU setting). Spinal osteomyelitis/epidural abscess. New HIV diagnosis (especially with advanced disease/complications). Acute endocarditis. Lyme disease (real or imagined). Recurrent UTIs in patients with GU anatomic abnormalities or spinal cord injury. Fever in the returning traveler. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial lung infection. Infectious complication following major surgery. Tuberculosis of any sort. Sexually transmitted infections. Transplant-related infections. And on and on and on …

Reason #3: Many of the time-consuming services ID doctors provide have no billing code. Which means, simply, you can’t charge for your work. Did you spend an hour searching for a critical culture result done at an outside hospital? Maybe it was the orthopedics consult on a patient with a septic hip, now in your hospital with essentially zero information in the chart. And once this patient is treated, who’s going to arrange his/her post-discharge IV antibiotics? The lab test follow-up? The vancomycin levels?

That’s right, it’s you, Dr. Bugsndrugs, and not Dr. Breakbone who can bill plenty for the time in the OR, while you can only hope your documentation on the initial consult note meets appropriate complexity criteria for a C4 or C5. (Don’t forget the review of systems.) The rest of the work listed above (aside from that first note) is essentially gratis. On a different case, did you spend an eternity searching for the resistance genotype done in 1999, relegated to the proverbial dust heap — but now it’s absolutely crucial to find it as you try to craft a new HIV regimen for a patient with significant side effects? What’s the billing code for that? And don’t get me started on curbside consults and other informal advice to colleagues — just read this.

There are certainly other reasons for the low salary: low income means you can’t invest in money-making imaging/scanners (just a few have a FibroScan), there’s no ID-drug equivalent to Lucentis, a high proportion of us work on salary for a hospital/clinic rather than in private practice, and many participate in infection control/quality improvement programs that earn points for citizenship but rarely salary.

Yet despite the low revenue, we still seem to be doing great with two key questions — if we had to do it all over again, would we:

1) Choose to go into medicine [that is, still become a doctor]?

2) Choose the same specialty?

Here, low-ish revenues notwithstanding, we do pretty darn well, finishing second among specialties in question #1, and eighth in question #2. All of which means we’re pretty satisfied with our jobs — hardly surprising given that we have the privilege of working in such an interesting field. Money isn’t everything.

Take it away, boys!

April 24th, 2014

Pioneering Measles Vaccine Researcher Has Anecdotes, Insight, Perspective, and Generosity to Spare

In the new IDSA/Oxford University Press journal Open Forum Infectious Diseases (OFID), we plan to interview a series of great figures in ID about their experiences, posting them as podcasts with accompanying scripts.

In the new IDSA/Oxford University Press journal Open Forum Infectious Diseases (OFID), we plan to interview a series of great figures in ID about their experiences, posting them as podcasts with accompanying scripts.

Our first interview is with Dr. Samuel Katz, a key figure in development of the measles vaccine, and it can be heard here.

It’s timely for several reasons. First, World Immunization Week starts today; second, MMWR just released a summary of the staggering health benefits of the “Vaccines for Children” program, created 20 years ago in response to the last big measles outbreak in this country; and third, the Annals of Internal Medicine has just published a thoughtful commentary on the difficulty of identifying measles in an era when so few clinicians have ever seen a case.

I encourage you to listen to the full interview, but here are some highlights:

- What it was like working in the lab of Nobel laureate John Enders

- How they tested the attenuated measles virus first in monkeys, and then on themselves (!)

- Planning and conducting the first clinical trial

- Expansion of the vaccine to international use

- How Dr. Katz views the anti-vaccine movement

There are some great stories in there, all suffused with an extraordinary generosity of spirit and humility. You’ve heard the phrase “humble to a fault”? We’ve got a prime candidate in Dr. Samuel Katz!

After all, what other medical advances have had quite the health benefits of a safe, highly effective vaccine — especially for a disease as contagious and potentially serious as measles? Or, to extract some key data from the MMWR cited above:

Because of vaccination, approximately 322 million illnesses, 21 million hospitalizations, and 732,000 premature deaths will be prevented among children born during [the past 20 years], at a cost savings to society of $1.38 trillion.

That pretty much says it all.

April 12th, 2014

Unwittingly, HCV “News” Brackets Our Current Treatment Era on Successive Days

I’ve already told you what a fan I am of Physician’s First Watch, the daily email summary of hot medical news provided by my colleagues here at the Massachusetts Medical Society.

If you haven’t signed up, you must do so — let’s play a short tune (always a favorite) for background music while you head over there and take care of it. I’ll still be here when you get back:

Finished? Great.

Anyway, this week the diligent First Watchers sent me this on Thursday:

The World Health Organization has issued its first recommendations on screening for and treating hepatitis C infection … Pegylated interferon with ribavirin is the recommended treatment.

Interferon plus ribavirin? Blast from the past.

Now of course the WHO guidelines are much more nuanced than that — the full document includes discussions of telaprevir, boceprevir, simeprevir, and sofosbuvir.

But on a day-to-day basis right now, in places lucky enough to have access to the newest drugs, sofosbuvir is part of every recommended regimen, so it’s startling to see interferon and ribavirin listed alone. And barely mentioned at all is the sofosbuvir plus simeprevir combination — a regimen astoundingly free of side effects, and arguably the treatment of choice today for virtually everyone with genotype 1 if drug costs were no issue. (Which they most emphatically are.)

By contrast, First Watch sent this off the very next day:

An 8-week course of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir was not inferior to a 12-week course, or to an 8-week course that also added ribavirin … Another research group studied the combination of a protease inhibitor (ABT-450)… plus two inhibitors of hepatitis C virus replication (ombitasvir and dasabuvir) for 12 weeks … [Both studies had] response rates of roughly 95%.

They were referring, of course, to two remarkable studies (here and here) just published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showing us what’s soon to come: both a sofosbuvir/ledipasvir single pill regimen for just 8 weeks, and an interferon-free approach that doesn’t include sofosbuvir at all.

So in the future we’ll have choices between several excellent options.

Now get over to the First Watch site and sign up. You won’t regret it.

April 8th, 2014

Would “HIV Controllers” Benefit from Antiretroviral Therapy?

Let me start with a disclosure — I’m the co-PI (along with Jon Li and Florencia Pereyra) on a study addressing the very question in the title.

The reason for this post is that the topic has been the beneficiary of some terrific coverage in Nature Medicine, both of this research question specifically and the whole topic of HIV controllers in general. Highly recommended.

Everyone who practices HIV medicine has encountered at least one of these lucky few who have low or even undetectable blood HIV RNA without antiretroviral drugs. And as you know, these HIV controllers represent a small subset of those with HIV — estimates vary, but it’s almost certainly < 1%.

Our message to them for years was that they didn’t need treatment, because they are already doing essentially the same thing with their own immune system.

But now there’s a body of evidence that this HIV control may have a downside, specifically an excess of immune activation and inflammation — which can, over the long term, have adverse effects on health. Cardiovascular disease (here and here). Lymphoid fibrosis. And a surprising report at CROI this year found a higher rate of hospitalization among HIV controllers compared to a control group of HIV patients who are receiving ART.

So would HIV controllers benefit from HIV treatment? That’s what we’re trying to answer — more details of the study, ACTG A5308, right here.

And if you have a few minutes, listen to this interview from Nature Medicine. It’s chock-full of thoughtful questions, and my best attempt to answer them!

April 5th, 2014

$0 for 30 Minutes of My Time? Sign Me Up!

Best e-mail survey ever, my second invitation from them — hence a “friendly reminder”:

|

Dear Sax, This is a friendly reminder about the online study we recently invited you to – X5328963_HCV Approximate interview length: 30 minutes By clicking the survey link below, you agree to participate under the terms specified above. Once complete, please click the link below to check your account balance and redeem any outstanding honoraria. Thank you for your time — your views are important to us. Gabriel |

Doctors get a lot of survey requests, but this is the first time I’ve received one that has so accurately estimated the dollar value of an ID specialists’ time.

Let’s see — if I do a hundred of these, what would my net be? Still zero?

Oh well. At least my views are important to them.

(Full disclosure: Survey links changed — last one to a candidate for the funniest four minutes… oh, just watch it.)