An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

October 13th, 2015

Yes, There Are Important HIV Studies at ICAAC and IDWeek — Here’s One

Both ICAAC and IDWeek (formerly IDSA) are now over, IDWeek ending this past Sunday.

Both ICAAC and IDWeek (formerly IDSA) are now over, IDWeek ending this past Sunday.

These are the two large Infectious Diseases scientific meetings that take place each year in the Fall. They’ve been battling it out for years for attendance, but it looks like finally IDWeek (formerly IDSA) has won the Fall slot — ICAAC is moving next year to the Spring, where I assume it will stay.

Regardless of which meeting one attends, or when they happen, a common complaint heard from HIV-specialist types goes like this:

Well, it’s not like CROI — hardly anything here new and important.

Well, of course it’s not like CROI — that’s a whole meeting devoted to HIV research, both clinical and basic. It’s unreasonable to expect there will be anywhere near the number of oral sessions, posters, and plenaries on HIV at non-CROI meetings because, obviously, ICAAC and IDWeek have to represent the full breadth of material in the field.

But there usually is some good stuff, studies that could significantly impact clinical practice. Here’s the most important HIV study from ICAAC, and soon the notable ones from IDWeek.

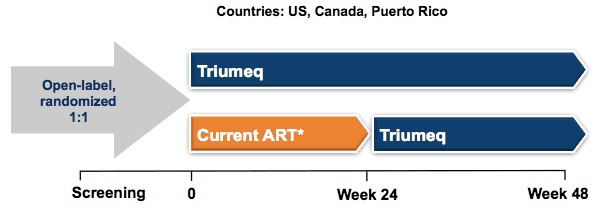

In the STRIIVING study, 551 virologically suppressed patients were randomized to stay on their regimen or to switch to ABC/3TC/DTG; it was open label (images thanks to the essential natap.org):

Eligibility criteria included being on first or second regimens with no history of treatment failure, and HLA-B*5701 negative.

At the end of 24 weeks, treatment success (HIV RNA < 50 copies by “snapshot”, meaning also still in study) was observed in 85% and 88% of subjects in the switch vs continue current ART arms respectively:

There were no virologic failures or emergent resistance in either arm. 4% (10 total — not 10% as I erroneously wrote) of the ABC/3TC/DTG group stopped the study due to adverse events (none considered serious) vs. zero in the continued ART arm. Treatment satisfaction at week 24 was significantly higher for those on ABC/3TC/DTG.

A few comments on these results, which were both reassuring and disappointing at the same time:

- There are now four available single-tablet treatments for HIV, and all have had prospective, randomized switch studies similar in many ways to this one — previously TDF/FTC/EFV, TDF/FTC/RPV, TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI for PI and NNRTI switches.

- Up until now, all of these studies numerically (if not significantly) favored the switch to the single tablet — not really surprising, as patients entering these studies typically want to simplify their regimens.

- Why didn’t this happen in STRIIVING? I can think of three kind of overlapping reasons: 1) A high proportion of subjects were already receiving integrase-based (and hence well-tolerated) treatments; 2) Also a high proportion were already on single-tablets; 3) All of these single-tablet treatments (before this one) would necessarily include TDF/FTC, and many of the multi-tablet regimens would as well. There’s probably a somewhat less-favorable tolerability profile of ABC compared with TDF, independent of hypersensitivity reactions (which didn’t happen in this study, obviously, since all were HLA-B*5701 negative).

An interesting irony is that the SINGLE study — which emphatically put DTG on the map — demonstrated superiority of ABC/3TC + DTG over TDF/FTC/EFV, results driven by better tolerability. Think about that one, and what it says about efavirenz.

Take-home message? Switching to ABC/3TC/DTG will mostly be successful (especially virologically), but a small fraction might have side effects that makes them prefer what they’ve already been on.

Anyway, that’s the most important HIV study at ICAAC. Coming soon, the most important one (or two or three, haven’t decided yet) at IDWeek.

Good time for a baseball moment. Congrats, Cub fans! (So far.)

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WOYME2Q4nAg&w=560&h=315]

October 7th, 2015

The Future of Diagnostic Microbiology, in 17 Minutes!

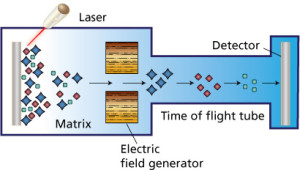

Over at Open Forum Infectious Diseases, I had the pleasure to interview Dr. Angela Caliendo about the latest advances in diagnostic microbiology. She touches on molecular testing in general, rapid pathogen identification (especially with MALDI-TOF, everyone’s favorite acronym), “syndromic” diagnostic testing for respiratory infections and diarrhea, use of Xpert for TB even here in the United States, and, of course the cost of implementing all these new technologies.

Over at Open Forum Infectious Diseases, I had the pleasure to interview Dr. Angela Caliendo about the latest advances in diagnostic microbiology. She touches on molecular testing in general, rapid pathogen identification (especially with MALDI-TOF, everyone’s favorite acronym), “syndromic” diagnostic testing for respiratory infections and diarrhea, use of Xpert for TB even here in the United States, and, of course the cost of implementing all these new technologies.

It’s incredibly entertaining, especially for ID geeks like me, and that’s because of the person I’m interviewing. Here are few key facts about Dr. Caliendo:

- She goes by Angie.

- She’s Professor of Medicine at Brown, and Vice Chair of the Department of Medicine. Before that, she was the Medical Director of the microbiology lab at Emory for 14 years.

- She’s one of those rare individuals who understands both the clinical and the laboratory side of medicine, an MD/PhD who really does blend both of those degrees.

- She’s an incredible teacher. If you’re looking for a Grand Rounds speaker on an ID topic, look no further!

- She’s been a major driver in the effort to improve diagnostics in Infectious Diseases, and was the lead author in this widely cited position paper.

Angie and I were medical residents and ID fellows together (a few years ago, ahem), and I can only remember one weakness (if you can call it that) — she has a horrible sense of direction. Really hopeless. I once told her to drive “towards the river” two blocks away from the Charles, and she looked at me as if I’d asked her to navigate to Mars. She admitted that she only knew where the river was if she could literally see it.

Aside from that, however, working with Angie was all gold.

Interview here, transcript here.

October 1st, 2015

WHO Decision to Recommend Treatment for All with HIV an Easy One — Now Comes the Hard Part

In the newspaper today — and yes, we still do get it delivered (some habits die hard) — is this headline:

Millions More Need H.I.V. Treatment, W.H.O. Says

It’s true — these updated guidelines say that all should be treated soon after diagnosis, regardless of CD4 cell count or whether they have symptoms.

Now, a certain non-ID doctor read the headline this morning, and asked me what the big deal is. After all, she’s been hearing about our treating everyone with HIV here for years — since 2012, if you want to be precise about it.

Even before that, in trendy San Francisco, the Department of Public Health in 2010 recommended treatment for all people with HIV regardless of CD4 cell count. Today this decision is paying big dividends in that city, with a decline in new HIV diagnoses probably linked to this policy in action.

Indeed, given the results of the START, TEMPRANO, and HPTN 052 studies, the WHO’s decision to modify its recommendation is about as surprising as Jerry’s telling George, Kramer, and Elaine that he wants to have lunch at Monk’s.

(Not sure why I thought of that analogy. Must be hungry.)

The data are now so overwhelmingly in favor of universal treatment of HIV infection that I can only think of one subset of patients for whom therapy has not been proven to be beneficial. These are the rare “HIV controllers” with undetectable virus and normal CD4 cell counts even without treatment. My hunch is that it probably benefits them too, though this is still under study.

The challenge, of course, is putting the “treat-all” policy into action. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the UNAIDS estimate of the proportion of people living with HIV who have been diagnosed is only 51%. Obviously, the other 49% are not getting any sort of treatment unless there is a massive HIV testing campaign.

In addition, treatment of everyone will likely strain both human resources and medication supply, with an additional 9 million people eligible for treatment but no new funding source to pay for it. As such, there’s an important statement in the guidelines about whom to treat if resources are limited:

Regardless of the epidemic profile and disease burden, priority should be given to people with symptomatic HIV disease or with CD4 count at or below 350 cells/mm3 who are at high risk of mortality and most likely to benefit from ART in the short term.

In other words, if you can’t treat everyone, treat the sickest first — they have much more to gain survival-wise than healthier people with HIV, so you definitely get more for your human and pharmaceutical investment.

But are clinical programs set up to do this? I suspect that with this recent WHO Guidelines change, most will operate under a “first-come, first-served” approach, offering treatment to everyone that shows up — until medication supplies run out or the clinic gets overwhelmed. As my colleague Ben Linas noted years ago when studying AIDS Drug Assistance Program waiting lists, this is not the best approach to maximize impact with limited resources.

The change in the WHO Guidelines, unsurprising as it might be, makes good sense scientifically. Time for a different sort of science — “implementation science” — to figure out how to make it happen, and how to benefit people the most.

Back to Monk’s.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8LafoDMH6Tw&w=420&h=315]

September 24th, 2015

Decision to Lower Price of Pyrimethamine a Good One, Especially Given the Weak Defense of the Price Hike

The big ID story the past couple of weeks is that the price of pyrimethamine — a drug that’s been available generically for decades — went from $13.50 to $750 for one pill after the exclusive rights to the drug were purchased by Turing Pharmaceuticals.

Now, after a barrage of criticism — all the way from this little blog to the Infectious Diseases Society of America to the New York Times to the leading Democratic candidate for President — the company has wisely decided to lower the price.

Exactly what the price will be remains to be seen, because there’s a lot of space between $13.50 and $750, but we’ll find out soon enough.

How about defense of the initial decision to raise the price?

Roll ’em:

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L-U1MMa0SHw&w=560&h=315]

There are a bunch of claims here that don’t quite ring quite true.

Namely:

- We don’t “desperately” need new treatments for toxoplasmosis [0’54”, those are minutes and seconds in the video]. Most people who have toxoplasmosis have asymptomatic latent infection and need no treatment. 90% of those that do develop active disease generally respond to the treatments we have. Clinically relevant resistance is, fortunately, a rare event. Alternative therapies (notably trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) are also pretty good, and have become standard-of-care in some settings.

- Treatment of toxoplasmosis does not cure it [5’22”] — if a patient’s immune system again becomes weakened, they can suffer a relapse even after they have been treated. This is why chronic suppressive therapy must be continued indefinitely if a patient remains immunocompromised.

- Patients with AIDS who need treatment don’t get a “very short treatment administration” [5’30”]. The HIV Opportunistic Infection Guidelines recommend 6 weeks of initial therapy, followed by chronic maintenance therapy until there is “an increase in CD4 counts to >200 cells/µL after ART that is sustained for more than 6 months.” In other words, patients treated for toxoplasmosis can easily be on treatment for a year, sometimes even longer.

The part around 2’30”, however, is undeniably true:

Profits are a great thing to maintain your corporate existence.

Look, there is nothing wrong with companies making profits for discovering, developing, and creating good products — this is a capitalist country, after all, and innovation should be rewarded. I write that sentence keenly aware that the new iPhones are about to appear in stores this weekend, and yes, my iPhone 4 is looking a little tired.

But with the pyrimethamine price increase, some sort of threshold of reasonableness was passed.

The negative response has been essentially universal, and quite appropriate.

September 20th, 2015

EHR and Drug Prescribing Warnings: The Good, the Bad, the Ugly

Recently, an ENT colleague (fictionally named “Clint” below), sent me two emails triggered by drug-drug interaction warnings he received while seeing HIV patients.

Here’s #1:

Hey Paul, I saw Mark C yesterday for hoarseness, and his exam was negative. Thought we’d try a PPI for reflux, but when I wrote the script, I got a warning that it interacted with Complera. Is this a real interaction?

Thanks,

Clint

And #2:

Paul, can’t believe I’m emailing you again. Same sort of question, different patient. Is there really an interaction between fluticasone nasal inhaler and ritonavir?

C

The answer, of course, is absolutely yes to both queries — these are very much “real” interactions, highly clinically significant. Rilpivirine (part of Complera) needs stomach acidity for adequate absorption. And the metabolism of fluticasone (and most other inhaled, injected, or even topical steroids) is blocked by ritonavir, raising systemic levels of the steroid and causing hypercortisolism — a very serious problem.

Good job, EHR! This is exactly what we want you to do, improve patient safety.

Part 2: The Bad.

But often the drug warnings aren’t really clinically relevant, and you just have to override (some would say “ignore”) them — which is why Clint the ENT (who, for the record, had never emailed me before) asked if these were “real” interactions.

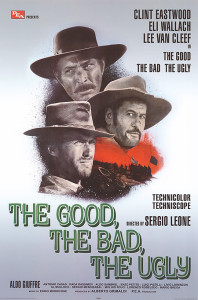

Here’s a common example every HIV/ID provider will recognize — the patient who has been receiving TDF/FTC, atazanavir, and ritonavir for years, is doing great, and needs a refill. Up comes the following:

The first one, with “high” importance, warns of the drug-lowering effects of tenofovir on atazanavir, decreasing its effectiveness — if given “without concurrent ritonavir.” (Emphasis mine.)

Hey, EHR — can’t you tell that the patient is receiving “concurrent ritonavir”? Certainly you’d think it were smart enough to do this, as the next warning, of “medium” importance, tells you that ritonavir increases atazanavir levels — exactly what we want when we give atazanavir with tenofovir. Just check out the atazanavir package insert and all the HIV treatment guidelines.

So practically we ignore both warnings, “high” and “medium” importance notwithstanding.

With warning messages like these, I suspect the following is going on: 1) No one has taken the time to teach the EHR that the complete regimen of tenofovir/FTC, atazanavir, and ritonavir should cancel these warnings; 2) the EHR doesn’t have the internal logic to check for multi-way interactions (the program generating the top-line “high” importance warning can’t read the “medium” one); or 3) some combination of the above, lost in a tangle of computer code and overwhelmed support staff.

Bad job, EHR! If warnings become too frequent, or are clinically irrelevant, this will generate “alarm fatigue.” A clinician becomes so overwhelmed by the number of warnings that he or she inevitably starts ignoring even the important ones.

Alarm fatigue is emphatically not just a problem for ICUs with their interminable beeps and buzzes, but also for EHRs. I know several primary care doctors who say they virtually always ignore them (especially on their younger patients), and housestaff entering orders on admitted patients routinely complain these alerts slow down their work, so they learn to click right through them.

If one were feeling generous, you could argue that with this “bad” example, it’s better for the EHR to err on the side of excessive caution, especially since these drug-drug interactions do exist and are at times clinically relevant — just not in this case. This problem should eventually sort itself out with greater human oversight and EHR sophistication.

(I’m an optimist.)

Part 3: The Ugly.

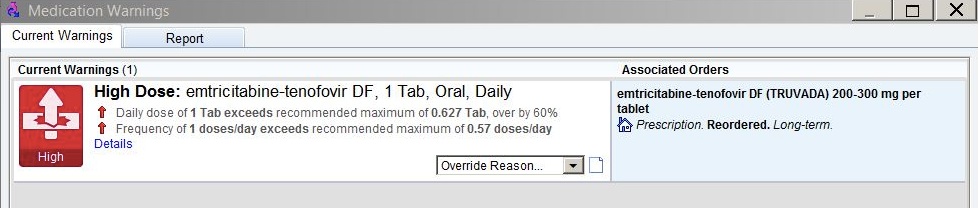

Finally, sometimes the EHR alerts are just baffling. This occurred last week as I was renewing tenofovir/FTC for a patient who, for the record, has been receiving the medication for years, has normal renal function, and normal weight.

For those of you who don’t prescribe it, the recommended dose is one tablet daily of the fixed-dose combination (only one form exists).

Up came this alert:

What the …. is going on here? I’ve prescribed this medication hundreds (maybe thousands) of times, and have never seen anything like it.

On what planet is the recommended maximum dose of tenofovir/FTC 0.627 tablets a day? Or the maximum frequency 0.57 doses a day? What does 0.57 doses a day even mean?

To make sure I’m wasn’t missing something, I’ve had two smart PharmD’s review my order, and they too are perplexed.

I reported the bogus alert, so right now, somewhere in EHR support land, a group is huddling (at least I hope they’re huddling) to try and figure out what generated this bizarre warning — one, of course, that I ignored. Or more accurately, a warning I overrode by telling the EHR that the “benefit outweighs risk” when I completed the prescription.

In short, Ugly EHR! And of course with this final example, this legendary quotation comes to mind:

To Err is Human; To Really Foul Things Up Requires a Computer

Great music here, even if you’re not a fan of Westerns:

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WCN5JJY_wiA&w=560&h=315]

September 13th, 2015

Station Eleven Is a Very Good Read — Even for ID Doctors

One of my colleagues, an MD/PhD, stopped me after our clinical conference a few weeks ago. He does basic science research, doesn’t see patients anymore — but he still comes to our clinical conference. Definitely scores points for that. And for being a very smart, interesting, and nice fellow.

One of my colleagues, an MD/PhD, stopped me after our clinical conference a few weeks ago. He does basic science research, doesn’t see patients anymore — but he still comes to our clinical conference. Definitely scores points for that. And for being a very smart, interesting, and nice fellow.

This was our conversation, reproduced verbatim:

HIM: Hey Pablo — got a book for you.

He’s called me “Pablo” ever since we went to Cuba for a scientific meeting four years ago. Yes, Cuba. Here are some pictures. And that’s one of Havana’s “taxi huevos” pictured above.

ME: Díme, Mateo.

For the record, neither one of us speaks Spanish very well. I’m pretty sure that means “Tell me, Matt”.

HIM: “Station Eleven.” It takes place in a dystopian future. Highly, highly recommended.

ME: I’m not really into science fiction. But my son is, I’ll let him know.

I’m imagining some Mad Max or Blade Runner-like thing, only a book. I can handle this post-apocalyptic theme in films (though for the record thought both of those movies were only so-so). But a whole novel? Skeptical.

HIM: It’s not really science fiction. Pretty much everyone is wiped out by the flu. It’s from the perspective of the survivors.

ME: I also don’t like books about ID topics written by non-ID doctors for non-medical readers. They get so many details wrong, it’s distracting.

Am I the only one with this view? I must have a dozen books given to me as gifts on ID topics, and most of them are terrible. One of the few I really enjoyed was My Own Country, by Abraham Verghese — and he’s an ID doctor.

HIM: No medical details, don’t worry. Weaves themes of love, art, music, journalism, religion — just what it means to be human. Really, really liked it. Tengo que leer!

I told you we don’t speak Spanish very well.

ME: OK, maybe I’ll give it a go.

Now at this point I’ll confess that the emphasis in that last sentence really should have been on the word maybe, because it just didn’t sound like the kind of book I’d enjoy.

Plus the world is filled with endless books waiting to be read, and there’s only so much time — especially with 1) Elvis Costello’s upcoming autobiography, which will be nearly 700 pages long; 2) wonderful baseball analysis like this available pretty much continuously; and 3) the imminent arrival of the next great flu pandemic, which promises to limit the free time we have available for reading quite substantially, especially if we are unlucky enough to perish in it.

But I was killing time in our neighborhood book store (how long before those are all gone, even without flu wiping us off the globe?), and the book was featured prominently in the displays. So I started reading it.

And you know what? Matt was right — it’s terrific. The author develops several interesting characters, shifts the story effortlessly between the pre-, immediately post-, and many decades post-flu periods, and strikes just the right tone when describing how humans live in a world without running water, cell phones, internet, electricity, cars, jets, or countries.

They do more than just survive — that’s what makes the book interesting, plausible, and, despite the grim plot, at times quite uplifting.

And, for the record, it has no embarrassingly incorrect medical information, though one might wonder at times how influenza could have a nearly 100% case fatality rate.

Small matter — it’s fiction, after all.

September 7th, 2015

Two Drugs with High Prices — One is (Surprise!) Good Value, The Other is Truly a Rip-off

By now, the fact that HCV treatment carries a high price is a fact as well known to the medical and non-medical public as 1) a million dollars doesn’t get you much in Manhattan or Bay-area real estate; 2) a Rolex is an expensive way to know what time it is; and 3) even though a Tesla doesn’t need gas, buying one won’t save you money.

By now, the fact that HCV treatment carries a high price is a fact as well known to the medical and non-medical public as 1) a million dollars doesn’t get you much in Manhattan or Bay-area real estate; 2) a Rolex is an expensive way to know what time it is; and 3) even though a Tesla doesn’t need gas, buying one won’t save you money.

But you know what? Something interesting has happened since the initial sticker-shock of the $1000/day pill and the cries of injustice from patients, the medical community, and activists. First, the price has been aggressively negotiated, and now is substantially lower — various unofficial estimates suggest the actual cost is around 50% of the wholesale acquisition cost. Still high, yes, but much less than the dizzying cost of HCV treatment during the “SIM-SOF” days in early 2014.

Second, a careful analysis of this miraculous therapy shows it’s actually decent value. In other words, you pay a lot, but you get a lot too — this is what the cost-effectiveness literature shows (several citations in bullet number two at this link), and the public is starting to take notice. An editorial last week in the Times got it right (though it could have used a bit of quick medical editing, which I’ve provided):

The benefits of these new drugs are undeniable. They can essentially cure [not essentially cure — they do cure] the infection in eight to 24 weeks… Curing the patient decreases by more than 80 percent the risk of liver cancer, liver failure and the need for a liver transplant, thus saving money in the long run. Successful treatment can also greatly reduce the number of new cases of hepatitis C by preventing transmission of the virus through needle-sharing among drug addicts infected with HIV [HIV has nothing to do with it]… the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, previously a skeptic, estimated that a likely course of treatment with Harvoni would make it a high value for individual patients and for most health care systems.

The editorial goes on to recommend lifting restrictions on treatment, in particular for those who don’t have advanced liver disease. This makes all kinds of medical sense, and will be great comfort to those of us battling with payors to get treatment to people before they have irreversible liver damage from HCV.

Meanwhile, one of our relatively obscure antimicrobials — pyrimethamine — has suddenly become staggeringly expensive. Used as part of treatment of toxoplasmosis (in particular for patients with AIDS), and rarely for malaria, pyrimethamine has been around for decades. A single pyrimethamine tablet, previously $13.50, now costs $750 — that’s a more than 50-fold increase.

It’s not as if new research funded by industry has found some novel indication for a previously underused drug. Nope, this is pure monopolistic pricing — in mid-August, a company purchased the rights to pyrimethamine, becoming the exclusive US distributor. As with the colchicine saga, this exclusivity allows them to dramatically drive up the price because, well, they can.

In short, sometimes you get what you pay for — and, at least in the case of pyrimethamine, sometimes you don’t.

Hey, this video doesn’t cover treatment, but it sure is funny!

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U9MU-FxsKRg?list=PLoeuxutUxJnkmhX6Rw9mBf_dDEkEy4-VH]

August 30th, 2015

(Not) Doing the Retinal Exam, and the Importance of Acknowledging Limitations

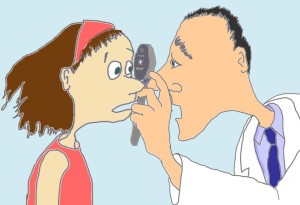

This past week, the New England Journal of Medicine released one of its excellent instructional videos, detailing how to do direct ophthalmoscopy to examine the retina.

This past week, the New England Journal of Medicine released one of its excellent instructional videos, detailing how to do direct ophthalmoscopy to examine the retina.

That’s the use of one of those hand-held gizmos — an ophthalmoscope, see picture on the right — to look at the back of the eye.

As usual, the video was clear, succinct and professionally done. A great resource for clinicians, young and old.

But here’s a confession — the video could be a nominee for this year’s Oscar for Best Picture, it wouldn’t help me a bit. Because I’m absolutely horrible at this procedure, always have been.

I’m as likely to see something important in someone’s eyes using an ophthalmoscope as I am using a shoe, an avocado, or a tennis racket (to choose three random things that happen to be in the room right now as I write this).

The inability to do a particular part of the physical examination creates some uncomfortable moments, in particular during medical school when learning the skill. Asked to acknowledge that yes, we do in fact see/hear/feel what we’re being taught to see/hear/feel, medical students face a dilemma when failing to do so. In essence, there are three options:

- Tell the truth: “I can’t see the venous pulsations” — and ask the instructor for more guidance right there on the spot.

- Lie: “Oh yeah, the optic disc margin is sharp” — this gives the teacher a sense that you’ve mastered the technique, but it’s basically cheating and a very bad idea in clinical medicine, for innumerable obvious reasons.

- Silence: Be quiet on the matter, blending into the background and allowing the class to move on — and remain hopeful that you’ll pick up the skill later with more practice.

I wish I could say I had the maturity to go with #1, but in fact #3 was the route I chose.

Even if I had chosen #1, however, I’m not sure it would have made much of a difference. The reason I can’t do this procedure is because my own eyes are so bad — which, for a variety of reasons having to do with the optics of it, make direct ophthalmoscopy virtually impossible.

Trust me on this one — it’s not just an excuse. (Of course it is.) The right eye is particularly useless, which means I’d have to use my left eye to look into a patient’s right eye. If you imagine doing this, it sets up a very uncomfortable nose-to-nose encounter with your patient — highly unhygienic and socially weird, a reason right there not even to try it.

In the face of limitations we have as doctors, we invariably come up with rationalizations to make ourselves feel better. And here are mine about this particular deficit:

- Visual complaints are serious business — wouldn’t this deserve a referral to a real pro, an ophthalmologist? You can be sure that in the CMV retinitis days, my threshold for referral was very very low.

- Similarly, let’s say I found something incidentally on ophthalmoscopy — certainly this would warrant having an ophthalmologist see the patient to confirm, right? What non-eye doctor would be 100% sure saying that what they visualized with their crude scope is benign?

- Direct ophthalmoscopy isn’t even the best technique to look at the retina — the indirect method is far superior, preferred by all retina specialists.

- There are many other things in medicine I can’t do (replace heart valves, biopsy colons, do immunohistochemical stains, interpret EEGs, remove thyroid tumors) — this is just one more.

- I may not be able to see someone’s retina (especially their right retina, see above), but I’m pretty good at listening to heart murmurs, if I do say so myself. Hey, I once noticed that a patient with endocarditis developed aortic insufficiency before the cardiologist did. Granted, she hadn’t seen him that day yet, but still …

In all seriousness, the real reason for this confession is that I’m pretty sure we all have limitations. Why else would the orthopedists consult us ID doctors for essentially every infectious complication on their patients, no matter how simple? After all, before their residency, these pre-orthopods were some of the smartest medical students — did they suddenly lose their brains when they began doing knee replacements?

Not a chance. It’s simply that at some point, it makes much more sense to acknowledge these limitations — and move on — than to pretend they don’t exist, or even worse, to fake it.

August 23rd, 2015

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis for HCV Can’t Be Cost-Effective — But We Might End Up Recommending It Anyway

An email query from a colleague:

Hi Paul,

Just got a call from one of our surgeons who got a needlestick from a suture needle, small amount of blood. Patient is HCV +. Any post-exposure prophylaxis recommended?

Thanks,

Dan

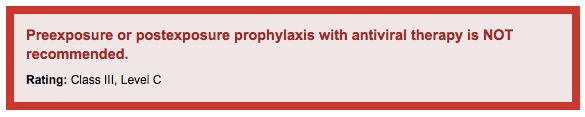

The quick answer is no, it’s not recommended. From the guidelines:

But it’s a natural question to ask for several reasons — on first blush, PEP for HCV seems like a no-brainer, because:

- It works for HIV.

- There’s no vaccine.

- Rate of transmission is approximately 10-fold higher than with HIV.

- The HCV drugs are practically side-effect free.

- It feels better doing something rather than nothing.

But despite the above issues that favor PEP today for HCV occupational exposures, there is absolutely zero chance this makes sense from a cost-effectiveness perspective. It’s just not possible.

A little refresher on basic principles of cost-effectiveness analysis: something is cost-effective if you get good value for your healthcare dollar. You spend more money, and you prolong life. How much you spend compared to standard-of-care, and how more much life you get in return gives you the numerator and denominator in that all-important cost-effectiveness ratio. In the USA, if we spend <$100,000 for an extra year of life, that’s considered cost-effective; <$50,000, very cost effective.

So let’s consider the HCV needlestick scenario, with 100 exposures; all assumptions will be biased in favor of PEP, just to make the point:

- The risk of acquiring HCV from a needlestick is 2-8%, depending on the nature of the exposure; some will clear it spontaneously. So if we do nothing, around 5 of these 100 exposures will end up with chronic HCV.

- Let’s assume that two weeks of PEP with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir will be 100% effective in preventing HCV acquisition. There are no data, but let’s give it the benefit of the doubt. And note that the HIV PEP protocol is 4 weeks, but at least one pilot study is using 2 weeks for HCV. (Why? Not sure.)

- Two weeks of PEP will cost $15,000 per patient — actually, a bit more, but let’s round it to $15K or a total of 1.5 million dollars for our 100 exposures.

- If we didn’t give PEP after the exposures, we’d need to treat the 5 people who contracted HCV with 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir, which would cost $450,000. All would be cured.

- The PEP strategy therefore costs $1,050,000 more than the no PEP one (1.5 million minus 450,000), and prevents 5 cases of HCV. That’s $210,000/case prevented — so a lot.

- What about survival, the denominator part of the cost-effectiveness ratio? The projected survival of those in whom HCV was prevented by PEP vs later cured with HCV treatment should be roughly the same (no one is getting cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma with early treatment) — but maybe there’s some “disutility” to getting HCV, even if it’s rapidly cured. So let’s give the PEP strategy a bit of a quality-adjusted survival advantage — how about 10 weeks, since that’s the extra time on treatment for an actual case? Of course we can only apply this to the 5 cases of HCV prevented in our 100 person cohort, so it’s an overall advantage of 0.5 weeks (10 weeks times 0.05), or roughly 0.01 years.

- Finally, we arrive at our cost effectiveness ratio, which is $1,050,000/0.01 years, or $105 million/quality-adjusted life year.

More than 100 million dollars for a quality-adjusted life year? Yep. I told you it couldn’t possibly be cost-effective.

Now again, I biased everything in favor of PEP. What if it doesn’t always work? What if failures of PEP lead to resistance? What if the PEP regimen needs to be 4 weeks long? What if the quality-of-life adjustment is an overestimate? What if some of the patients who get HCV have a very low HCV RNA, and can be cured with 8 weeks, not 12?

Well, then you’d be spending even more than $105 million dollars per year of life saved. But whether it’s $105 million, or even half my back-of-the-envelope estimates (which could be wrong — I was an English major, after all), the point remains: This can’t be a cost-effective intervention.

But as I was sharing these thoughts with my brilliant friend and colleague Rochelle Walensky, who does this stuff for a living, she reminded me of this important fact:

I might encourage you to acknowledge that many of these kinds of decisions (PEP, safety of the blood supply) are not made on cost-effectiveness grounds … Most of the cost-effectiveness data for the screening for the blood supply demonstrates it’s not at all cost effective. You may want to acknowledge that point (we pay more for lots of things that cost-effectiveness suggests we shouldn’t, including keeping health workers safe given their dedication to care, keeping blood supply safe etc).

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RSBaEz10sQk&w=560&h=315]

August 17th, 2015

Dog Days of Summer ID Link-o-Rama

A few ID/HIV items of note to consider as you gather up your sunscreen, flip flops, towels, and sand toys and head off to the beach:

- Interesting review of the impact of low socioeconomic status in the recent outbreak of Legionnaires’ Disease in the South Bronx. It’s just like (almost) every infection — the combined effects of crowding, poor sanitation, and high levels of other comorbid diseases greatly amplify the risk of getting this disease.

- Want an exception to this rule? How about Lyme Disease? Quite the statement that the linked article appeared in the Fashion and Style section of the Times! And here’s the first paragraph: “At a recent dinner party in Greenwich, Conn., Topic A was not stock futures or boarding school, but something decidedly less tony: ticks.”

- Which is emphatically not to say that Lyme is a small problem, or just the product of the overactive imagination of the worried-well leisure class. An upcoming paper in Emerging Infectious Diseases estimates there are around 329,000 cases annually. And if you want to see the highest incidence locations, here’s a remarkable map from last month’s issue.

- Last tick item, promise (though it is the season) — I’ve noticed a bunch of sites now refer to the Ixodes tick vector for Lyme-anaplasma-babesia as the “blacklegged” tick instead of the “deer tick.” When did that happen? Did the deer get the memo from the variegated squirrels, and are now protesting? What about all the other creatures with black legs? How do you think they feel?

- Daclatasvir is now available, and the excellent HCV treatment guidelines have been updated. The most important change is the recommendation for treatment of genotype 3 — 12 weeks of daclatasvir/sofosbuvir if no cirrhosis, 24 weeks (with or without RBV) with cirrhosis.

- Several more important HIV/HCV coinfection studies published: sofosbuvir/ledpasvir, sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir, and grazoprevir/elbasvir. (Last of these slated for approval within 6 months.) All have outstanding (>95%) cure rates, comparable to those without HIV. It’s the drug-drug interactions that need watching — very useful figure here.

- This meta analysis found impressive benefits of corticosteroids as adjunctive treatment for community acquired pneumonia. Probably not ready for standard-of-care (yet), and I like the suggestion from the editorialist to find surrogates (clinical or lab-based) for which patients would benefit the most.

- The updated flu vaccine guidelines have been released, and as usual they are quite a mouthful: “The vaccines will contain hemagglutinin (HA) derived from an A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)-like virus, an A/Switzerland/9715293/2013 (H3N2)-like virus, and a B/Phuket/3073/2013-like (Yamagata lineage) virus … Quadrivalent influenza vaccines will contain these vaccine viruses, and a B/Brisbane/60/2008-like (Victoria lineage) virus.” Got that? Report also includes updates on the live attenuated vaccine, and indications for vaccination in general, which include basically everyone.

- Long-term valacyclovir provides no benefit after HSV encephalitis. An important negative study, it could not have been easy to identify eligible patients and enroll them. (It took nearly 10 years to complete.) The overall excellent outcome in both arms — 86-90% with mild or no neurologic sequelae at 2 years — likely reflects the exclusion of the sickest patients with this scary condition.

- Anyone notice an association between abacavir and anxiety? Link is to an observation (and a couple of published case reports, though the second one could have been EFV) from long-time HIV/AIDS advocate, Nelson Vergel. I personally have not seen this side effect, though it does seem that some people starting integrase-based treatments (including dolutegravir) develop insomnia.

- Baseball/ID overlap warning — Los Angeles Dodger fans are no doubt happy that their excellent third-baseman Justin Turner is off the disabled list after a bad bout of MRSA. Contact precautions in the locker room? Gowns and gloves when he comes to bat? Purell stations at each base?

Title of this post notwithstanding, the weather in Boston this summer has been great — mostly warm days, cool nights, low humidity — hence the energetic jumping pooch in the picture (not mine, click on it for full effect). I just love the phrase, “dog days of summer”, and wanted an excuse to use it.

Hey, it’s hot somewhere!

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pl_wK6pOmxE&w=560&h=315]