An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

January 27th, 2016

Here’s an Idea: Justify Your Specialty’s (Low) Relative Salary Using Moral Superiority

In an otherwise excellent piece on recruitment to the ID field from the pages of Infectious Diseases News, comes this:

But while inadequate compensation [for ID doctors] may hamper recruitment, it also could prove beneficial to some degree … Reduced salaries filter out the less-passionate applicants in favor of those who are more dedicated to their patients and to research within the field … “People obviously don’t go into infectious disease as a get-rich-quick scheme … Let’s say the infectious disease reimbursement was double what it is now. There undoubtedly would be more people electing to go into infectious disease, but are they the kind of people we want? I won’t answer that question, but it is certainly something to think about.”

Good grief.

Now look — I understand that money shouldn’t be the primary motivation for a career choice. And furthermore, I’m in total agreement that when some lofty celebrity, athlete, or executive chooses a suspect path based on what appear to be solely financial incentives, it’s reasonable to question the wisdom of their decision.

But are we really ready to justify low ID reimbursement as a way of drawing the most committed doctors to the field?

If so, then let’s cut the salaries even further! Let’s see if I’ve got the math right, using the example above only going in the opposite direction:

Low salaries for ID doctors → More dedication to the field.

Cut salaries 50% → Double how dedicated ID doctors are to what they do.

Result: A 2X stronger pool of ID docs.

This is nonsense, of course.

In the current reality of heavy medical school debts, other subspecialty options, subsidized hospitalist salaries, and the need for extra years of fellowship training, it stands to reason that lower paid specialties such as ID are going to suffer.

No sense justifying this pay gap by some unsubstantiated claim of moral superiority.

Instead, we should be aggressively lobbying that what ID docs do — which is improve patient outcomes, manage complex cases, support other clinicians, deal with public health emergencies, establish protocols and policies, and reduce unnecessary costs — brings value to the healthcare system, and be dutifully acknowledged. Read here for more.

Thank you.

The following video has nothing to do with the above rant, but sure is amazing.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vdTrr_VRKgU&w=560&h=315]

January 18th, 2016

IV and Injectable HIV Treatments Are Much Discussed — But Won’t Be Here Anytime Soon

Something interesting happens when you poll people who treat HIV — and people who have HIV — about whether they’d prefer a treatment option that consists of a periodic injection or infusion in place of the pill or pills that they take every day.

Something interesting happens when you poll people who treat HIV — and people who have HIV — about whether they’d prefer a treatment option that consists of a periodic injection or infusion in place of the pill or pills that they take every day.

Lots of them say yes. Even people who are taking just one pill a day, and are having no side effects.

As a famous comedian (repeatedly) says, What’s the deal with that?

Given the success of currently available oral therapies — in which essentially 100% of people who take it are virologically suppressed — why do so many people say they want shots instead?

Part of it, of course, is the way the question is framed, and human nature. There’s a tendency to favor the shiney new toy. Here’s a typical headline on this topic:

And the simple question — “Would you prefer a shot over pills?” — implies an optimal available strategy. Let’s imagine a single shot administered quarterly, with a small required volume, low rates of injection site reactions, few side effects, and plenty of forgiveness around missed doses. Now we’re talking!

The reason I bring this up is because a couple of recent studies show that non-pill treatments for HIV are at the very least feasible.

Most promisingly, there’s the LATTE-2 study of the long-acting antivirals cabotegravir and rilpivirine — given as injections either every 4 or every 8 weeks — which maintained virologic suppression as well as a standard 3 drug regimen. (More details expected soon.)

And there’s this study of the broadly neutralizing antibody VRC01, which when infused to patients with viremia, dropped HIV RNA 1.1-1.8 log (10-100 fold) in 6 of 8 with a single infusion. It follows an earlier study showing an even more potent antiviral response using a different antibody, 3BNC117. Both treatments dropped HIV RNA long after the single dose.

So we’re on our way, right? Soon we’ll be offering injections or infusions as an alternative to pills, and we’ll all live happily ever after!

But it’s not so simple. Here are a few compelling reasons why we’re not going to see these injectables as viable treatment options in the near future:

- Current treatment is really, really good. Let’s start with the obvious one. Out of 100 newly diagnosed patients, how many can’t get by with one of the Recommended or Alternative DHHS regimens? So the motivation to develop long-acting injectable treatments isn’t quite a life or death matter. “But not everyone can take pills every day,” you say. Indeed that’s true, but …

- Many poorly adherent patients would be lousy candidates for long-acting therapies. This is counterintuitive, as they are the first group one would consider for injectable treatments — people who don’t take their meds now. But to be eligible for cabotegravir plus rilpivirine maintenance therapy, first virologic suppression needs to be achieved — which requires adherence to pills. An oral lead-in is also prudent to screen for acute toxicities that would be very tricky to reverse given the 40-day half-life of injectable cabotegravir. “You’re not getting it back once you inject it,” is what one PharmD memorably said. Finally, what if this non-adherent person decides to be non-adherent to the injections? Misses a few scheduled shots? Takes off for Honduras, as one of my intermittently compliant patient unpredictably does, sometimes with and sometimes without his prescribed ART. Then you have the l – o – n – g tail of low drug levels, which could allow for virologic rebound and selection of resistance.

- So far, it’s not even close to a “simple injection.” It’s not like an insulin shot, or a flu vaccine. The cabotegravir/rilpivirine treatment will almost certainly be at least two intramuscular injections, volume and time between doses to be determined. And monoclonal antibody treatments will likely require an infusion of some sort — time consuming!

- Use of broadly neutralizing antibodies for treatment has many significant hurdles. These “bNAbs” (as they’re cleverly nicknamed) are fascinating scientifically, but will be a bear to get into a practical treatment regimen. Here are a few issues to consider: 1) Some patients have pre-treatment resistance (2 of 8 in the VRC01 study, for example) — will this require a pre-therapy test, akin to viral tropism testing? 2) Treatment selects for escape mutants — in other words, resistance. Combination therapy will be required, perhaps with complimentary bNAbs — will each require a separate pre-therapy test to determine susceptibility? 3) Monoclonal antibody treatments can be antigenic, triggering allergic reactions. 4) If penetration into the CNS is important for at least some component of ART, these monoclonal antibodies aren’t getting there. 5) See above regarding infusion time. All in all, I confess to not quite getting the fascination with bNAbs for treatment, but maybe that’s just me.

- The entire regimen has to be long acting, and preferably also not require pills. If there’s a parenteral therapy that can be given every 2 months, but patients still need to take pills every day to complement the treatment, what’s the point? This is why the cabotegravir/rilpivirine regimen is so far ahead of anything else.

Granted, even as the cabotegravir/rilpivirine treatment is currently configured — a few shots every 8 weeks — there will be a subset of patients for whom this is their preferred way of receiving therapy. Could be cost-effective, too, especially if it’s priced reasonably.

But I’m thinking it’s going to be small group who actually prefer this treatment to a single pill a day. And we’re not going to see it anytime soon.

Pop Tarts, Jerry?

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=itWxXyCfW5s]

January 10th, 2016

Medical Marijuana and Painful Neuropathy — An Opportunity to Make Us Believers

Medical marijuana is now officially available in New York, the city with by far the largest number of people living with HIV/AIDS in the country. Reporting on the first dispensary in Manhattan, the aptly named Julie Weed (yes! her real name!) writes:

Medical marijuana is now officially available in New York, the city with by far the largest number of people living with HIV/AIDS in the country. Reporting on the first dispensary in Manhattan, the aptly named Julie Weed (yes! her real name!) writes:

One of the most promising areas for research is the substitution of medical marijuana for opioids like OxyContin and Percocet for pain management …“68% of our patients with AIDS-related neuropathy have said that medical marijuana has allowed them to stop taking opioid prescription pain killers which can be addictive, cause a variety of harmful side-effects, and — most critically – are the cause of thousands of overdose deaths per year.”

Some thoughts based on this claim, and the long history of medical marijuana and HIV/AIDS:

- Could 68% of patients with painful peripheral neuropathy really stop opioid pain killers with marijuana? Wow. If that’s true, it’s huge — even half this rate would be a dramatic advance. Among the most frustrating conditions in all of medicine, painful peripheral neuropathy has a list of treatments as varied as the products sold in the “Cough and Cold” aisle at your pharmacy — and are, unfortunately, about equally effective. Proven strategies to help people come off chronic narcotics are badly needed.

- HIV specialists have been hearing about the medical use of marijuana even longer than we’ve had effective antiretroviral therapy. Initially touted as an appetite stimulant for HIV-related anorexia and weight loss, and as palliative therapy to ease the pain of death and dying, it gained further use in the mid-1990s when early HIV-related combination regimens caused so much nausea. This randomized clinical trial led by Donald Abrams — who has done some of the best work studying marijuana in HIV against great odds — found that 5 days of smoked cannabis was more effective than placebo in 50 patients with painful peripheral neuropathy. Of course blinding the study arms was (and remains) essentially impossible given the euphoric effects of the drug, but maybe that’s the whole point.

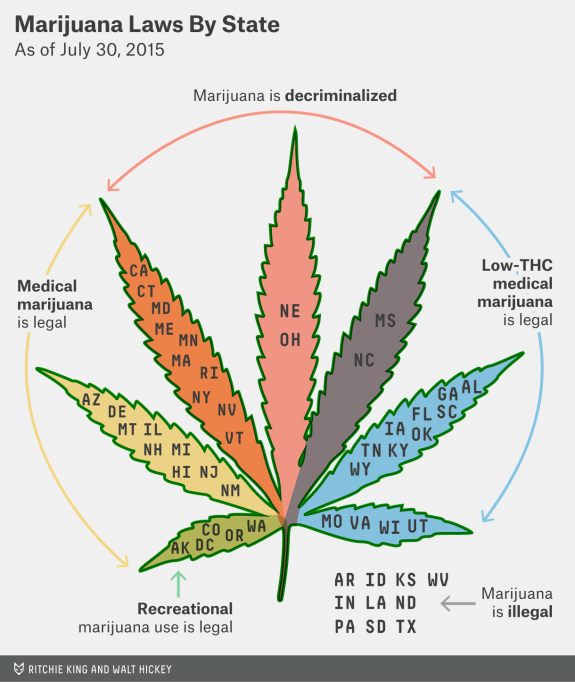

- Just legalize the stuff already. That’s how I’d characterize the opinion on marijuana for the vast majority of the doctors, nurses, and social workers I work with, some of whom (like me) both remember Woodstock (the original one, kids) and enjoy the music from it, or are younger, and have the same view. If marijuana is legalized, it can be more easily regulated, taxed, and studied (see below) — just like that other legal psychoactive drug, alcohol. Seems like this is hardly a minority view (the link is to the source of the graphic at the top of the page).

- Legalization would allow more rigorous studies of therapeutic use, long-term effects, and safety. Such studies are now essentially prohibited by the federal government since marijuana is considered a drug of abuse. As a result, many claims about its medical indications are based on either small, short term, or methodologically questionable studies or, even worse, strongly-held beliefs based mostly on anecdote — the weakest form of scientific evidence. That is, I’m afraid, what that “68% have stopped their opiates” claim is from the opening paragraph. Until it’s studied more rigorously, we’re stuck with the frustration of dealing with claims that marijuana is a valid treatment for practically every chronic condition under the sun. A similar claim might be made of benzodiazepines like Valium, Xanax, and Klonopin — which definitely make people feel better — but clinical research has more clearly defined both the benefits and risks of this drug class.

- The quasi-medical atmosphere of some marijuana dispensaries is a huge negative to the acceptance of legitimate medical use. Got a free 10 minutes? That plus saying you have “insomnia” gets you a weed license for the medical stuff in Venice, no medical records required. Medical marijuana exists in this bizarre parallel system to “real” FDA approved drugs, and the absence of good scientific data means that the indications for use state-by-state are literally and figuratively all over the map. Got to love this indication (and I use the word loosely) for medical use from California: “Any other chronic or persistent medical symptom that substantially limits the ability of the person to conduct one or more major life activities (as defined by the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990) or, if not alleviated, may cause serious harm to the patient’s safety or physical or mental health.” If it’s based on patient report, that covers pretty much anything, doesn’t it?

So what’s my take right now? Count me in the same camp as these authors, who published their views in a JAMA editorial last year, writing:

If the states’ initiative to legalize medical marijuana is merely a veiled step toward allowing access to recreational marijuana, then the medical community should be left out of the process, and instead marijuana should be decriminalized … Evidence justifying marijuana use for various medical conditions will require the conduct of adequately powered, double-blind, randomized, placebo/active controlled clinical trials to test its short- and long-term efficacy and safety. The federal government and states should support medical marijuana research.

Totally agree. Meanwhile, here’s a study design free for the taking:

Title: A randomized, blinded study of cannabis versus placebo to reduce opiate use in HIV-related neuropathic pain.

Entry criteria: Painful HIV-related neuropathy for ≥3 months, confirmed by a neurologist at screening, and requiring the use of opiates for control. Stable doses of opiates for at least 4 weeks prior to screening are required. HIV RNA must be < 50 copies/mL on non-neurotoxic containing ART.

Intervention: Smoked cannabis or placebo for 24 weeks; up to daily use as desired by study subjects. Adjunctive therapies (gabapentin, antiepileptics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acupuncture) will be administered at the discretion of the investigators.

Primary endpoint: Time to cessation of opiate use as estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method.

Secondary endpoints: Time to reduction in 25, 50, and 75% of opiate use; absolute and relative reduction in opiate dose. Proportion opiate free at study completion. And what the hell, might as well also do Numeric Pain Rating Scale, Change in Pain Inventory Score, Numeric Rating Scale Sleep Interference Score, Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale, Patient Global Impression of Change of Pain, and all those other neuropathy assessments. Throw in some neurocognitive testing just for fun.

Funding: National Institutes of Health

You’re welcome!

Let’s see if what you think.

January 4th, 2016

A Riddle, the 2015 Clinical Trial of the Year, and a Guaranteed Laugh for All ID Doctors

Things quiet on this end recently from me due to various circumstances. but here are three ID-related (sort of) things worth sharing — enjoy if you haven’t seen them already.

Let’s start with a riddle:

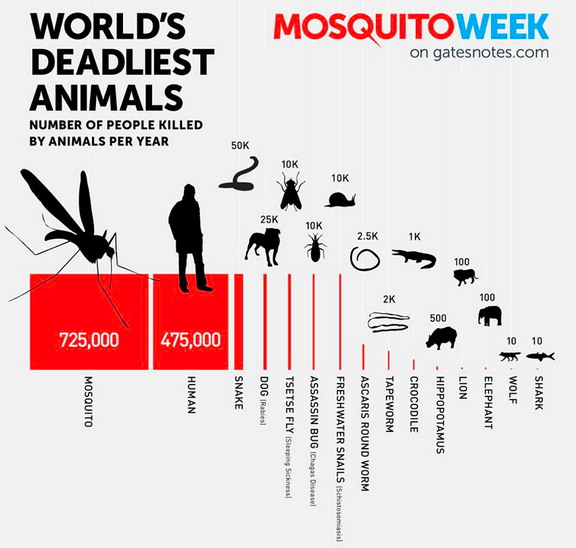

- What animal is responsible for the most human deaths a year?

Readers of Bill Gates’ blog will think this is old news, but not everyone has seen that incredibly cool graphic. (Me, for example.)There’s zero chance I would have gotten this riddle right, even with several hours to think about it, and even with all the Zika news buzzing around (word choice intentional). Makes one think that the CRISPR projects targeting these nasty pests — so long, malaria? — are on to something, though inevitably there will be downstream consequences.

If asked, I’d have put humans first by a long shot, then maybe something like bears, which don’t even make the list, then perhaps crocodiles (still pretty scary, though not much of a threat in New England, and only one-tenth as deadly as snails). Not octupuses (which I’ve learned is the correct plural, emphatically not octupi). Or rabbits.

And who knew Gates was such a book fiend? Impressive.

- The most controversial clinical trial of 2015.

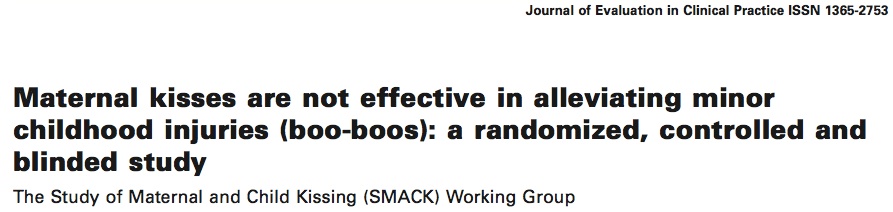

It came late in the year, so you might have missed it. From The Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, here’s the full title:

Now you have no excuse. RTFA, as they say.You can imagine that this study has generated quite a bit of discussion at our family’s Journal Club, which consists of a pediatrician (my wife), an ID doctor (me), and my dog Louie, who by the graphic displayed in #1 above is the 4th most dangerous animal in the world. Easy to believe by looking at this ferocious picture.Louie was his usual taciturn self when we discussed this paper, while my wife strongly objected to the conclusion that maternal kisses don’t help cure minor boo-boos. Meanwhile, I’m wondering what kind of wound irrigation they used — low, medium, or high pressure — and whether they used prophylactic cefazolin, or vancomycin, or perhaps something that covers oral flora.

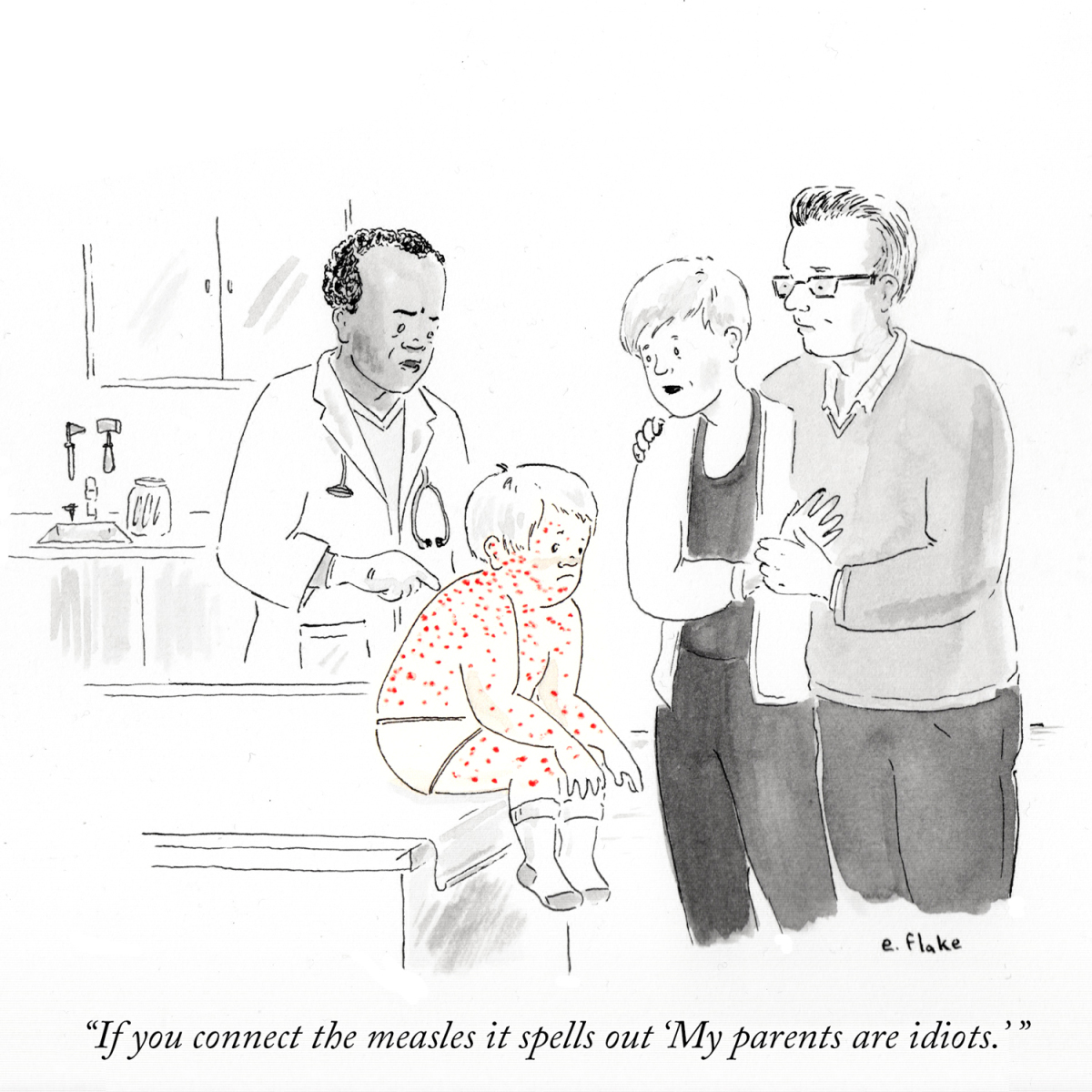

- The funniest ID-related cartoon of 2015. Nothing else even comes close.

(H/T to David Paltiel for the boo-boo study.)

December 26th, 2015

A Few Things We Were Talking About On Rounds …

Remember when people passed out papers of interesting clinical studies and relevant reviews? And how some doctors even had a special stamp they put in the upper right hand corner?

Remember when people passed out papers of interesting clinical studies and relevant reviews? And how some doctors even had a special stamp they put in the upper right hand corner?

OK, full confession — I did that. A lot. See evidence to the right. Haven’t used the thing in well over a decade, surprised I still have it. Amazingly, it still works, though the print is getting somewhat faint.

But why did I do that? Some indirect way of getting credit for the literature search-library run-photocopying? A way of preventing reprint theft? (Never much of a crime.) Just too lazy to write out my (very short) name? I do have terrible handwriting.

Kind of ridiculous, when you think about it for a moment.

I thought of this bygone practice since I just finished some time on service, and mentioned various studies while on rounds. Passed out zero papers, for the record.

But to prove to the excellent fellow with whom I was working that the studies weren’t just made up, here are a few that came up:

- Dalbavancin is the long-acting lipoglycopeptide that is FDA-approved for skin infections , the two doses separated by a week; oritavancin is approved for just single-dose therapy. But this study of skin and soft tissue infections suggests that dalbavancin given as just one dose is just as effective as the two dose regimen. It also doesn’t require the lengthy infusion time of oritavancin — only 30 minutes for dalbavancin, 3 hours for oritavancin.

- Toxoplasmosis treatment is much in the news these days, thanks to the 5000% pyrimethamine price hike — and the always entertaining and recently arrested former CEO of the company that owns the rights to the drug. The price increase has forced many of us to adopt what most other countries (and the transplant docs) have done for years, which is to use trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for toxo — an antibiotic that is cheap, readily available, and can be given either IV or PO. But what’s the dose? This small randomized clinical trial used 5 mg/kg of the TMP component q12h, and found it was better tolerated and just as effective as pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine; this dose is also listed in the OI Guidelines, and it comes out to 2-3 DS tablets twice daily. Some recommend twice this dose based on other studies. Regardless, take that, Mr. Shkreli!

- Leuconostoc is not only one of the few gram positive cocci intrinsically resistant to vancomycin, it’s also not reliably sensitive to linezolid. And boy does it sound weird — a bacterium named by Russians? Who named it while working in Vladivostok? Treatment of choice is penicillin, but susceptibility testing is critical since resistance can occur. Macrolides, tetracyclines, carbapenems are also usually active. Here’s a recent case report of successful treatment with tigecycline.

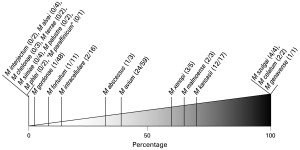

Mycobacterium gordonae is a slow-growing non-tuberculous mycobacteria that can sometimes cause clinically important infection, but is much more likely to be a colonizer or contaminant — figure to the right is proportion of pulmonary isolates that caused real disease among NTMs in the Netherlands. M gordonae is commonly found in tap water, and also is infamous for causing pseudo-outbreaks through its propensity to colonize bronchoscopes, ice machines, cleaning devices, etc.

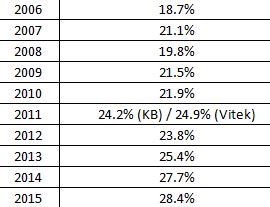

Mycobacterium gordonae is a slow-growing non-tuberculous mycobacteria that can sometimes cause clinically important infection, but is much more likely to be a colonizer or contaminant — figure to the right is proportion of pulmonary isolates that caused real disease among NTMs in the Netherlands. M gordonae is commonly found in tap water, and also is infamous for causing pseudo-outbreaks through its propensity to colonize bronchoscopes, ice machines, cleaning devices, etc.- Penicillin-sensitive Staph aureus is on the rise! Here are the percentage of MSSA that are also penicillin-sensitive according to WHONET (H/T to Michael Calderwood):

Our hospital has similar rates. No one (I don’t think) has any idea why this is happening — theories welcome. And we continue to be surprised by the latest endocarditis guidelines, which recommend nafcillin or oxacillin for all MSSA regardless of penicillin sensitivity — though many experts (including those who taught me) will choose penicillin if susceptibility is confirmed, since it is more active in vitro, and there is this suggestive study. The key is that the micro lab just needs to do the extra step of confirming absence of inducible beta lactamase — not difficult, and potentially clinically relevant.

Our hospital has similar rates. No one (I don’t think) has any idea why this is happening — theories welcome. And we continue to be surprised by the latest endocarditis guidelines, which recommend nafcillin or oxacillin for all MSSA regardless of penicillin sensitivity — though many experts (including those who taught me) will choose penicillin if susceptibility is confirmed, since it is more active in vitro, and there is this suggestive study. The key is that the micro lab just needs to do the extra step of confirming absence of inducible beta lactamase — not difficult, and potentially clinically relevant. - Nitrofurantoin should not be prescribed to patients with creatinine clearance < 40 due to lower efficacy and increased toxicity — accumulation of toxic nitrofurantoin-derived metabolites can occur. That means it’s not an option for the 90-year-old woman admitted with a UTI and a creatinine of 1.6 (which for the record calculates to an estimated creatinine clearance of around 20). Great recent review of nitrofurantoin here, which is particularly helpful since use of this drug has increased enormously since the change in the UTI guidelines and the rise in fluoroquinolone and TMP-SMX gram negative resistance.

Hey, hope the holidays brought you got some wonderful presents — something better than these items in the video below, which could be less useful than my stamp thing (which at least takes up almost no space in the back of my desk):

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FgFeVlw2Ywg]

December 19th, 2015

Part 2, Now The Good News: Why ID Will Survive as a Specialty

Part 1 of this post, which highlighted the primary reason for declining applications to ID fellowship programs, could come across as something of a downer.

Part 1 of this post, which highlighted the primary reason for declining applications to ID fellowship programs, could come across as something of a downer.

“Moping about it won’t get us anywhere,” someone said to me, and it’s true nobody likes a whiner. But my point was to acknowledge the issue, and find a way forward. It wasn’t a whine, it was an analysis.

And I concluded with the following:

Fix the money problem, and the interest in ID will rebound nicely.

So why am still optimistic about the future of ID as a specialty? Many reasons.

Here:

- We still attract lots of the top medical residents to ID. Chief Medical Resident-types. Outstanding researchers. Residents who want to make a difference in the world. Residents who are are not motivated primarily by the money — which for ID may not be in derm-ophtho-cards-GI-radiology territory, but it’s not that bad, c’mon. Our residents who match in ID know that the best cases in the hospital and in clinic are often ID cases — where history, physical, lab findings, and therapeutics all line up for a fascinating story — and these cases are frequently featured in morning reports, CPCs, grand rounds, and other teaching venues. They also know that the research, policy, and public health opportunities in ID are almost limitless. Finally, they know about the reputation of ID doctors in the hospital and beyond. Read on.

- ID doctors are often considered the best overall clinicians out there. Ok, ok, I’m biased. But how often have you heard someone say that if they really want to know what’s going on with a complex patient, they first read the ID note? And how about this comment from Loretta S, a PCP (and one of my favorite readers): “I know the ID doc is going to have to spend countless hours reviewing the patient’s history, reviewing old labs, ordering and interpreting new labs and just generally doing deep thinking … The patients are often those for whom we in primary care are out of ideas, and we hope ID can somehow puzzle things out. And then, on top of everything, this amazing, detailed consult note comes back and I learn something new. All of which makes me, a nerd, sometimes wish I worked in ID!” Thank you Loretta. I remember during my fellowship, the Chief Resident in surgery was watching us evaluate a post-op patient with unexplained fever, and said: “Please save him, because if you guys can’t, no one can.” Thank you. (For the record, we did. It was a pulmonary embolism.)

- The field has incredible, unmatched diversity. This is a partial list of what ID has to offer: 1) “Every organ system” involved, as ID fellow applicants frequently (and accurately) point out. As a result, we see patients from every specialty, both medical and surgical — they all need us. 2) Hospital-based and outpatient-based problems, you can choose either one or both. 3) Epidemiology and public health. 4) Infection control and antibiotic stewardship. 5) The rapidly expanding world of ID diagnostics. 6) Transformative advances in therapeutics (HIV and HCV two dramatic examples, perhaps unparalleled in all of medicine). 7) The role of the microbiome, in sickness and health. 8) Infections in transplant recipients and other immunocompromised hosts. 9) Tropical and travel medicine. 10) Sexually transmitted infections. 10) Emerging infectious diseases — 10 years ago, who ever heard of Chikungunya? Or 2 years ago, Zika virus? 11) Device-related infections. 12) Tuberculosis and other mycobacterial infections. 13) Infectious complications of pregnancy. 14) Malaria and other parasitic disease. 15) ID in critical care/sepsis. 16) Immunizations and other preventive strategies … I could go on and on and on, you get the idea. In a wonderful piece about ID doctors published a few years ago, there’s this great quote from Dr. Jerome Levine, an ID doctor in New Jersey:

“Never once in all my 28 years of practice have I ever been bored,” says Levine, echoing a refrain just about universal among his colleagues.

Yes, universal!

- Care that includes ID doctors improves outcome. Maybe it’s our meticulous attention to detail. Maybe it’s our involvement with literally all the hospital services and specialties (see above). Maybe it’s because we take the best histories. Or maybe it’s just because we’re just so darned smart — there’s a minimum IQ requirement for ID

certification of 140 — 130 won’t cut it, sorry. (If you’re so smart, why didn’t you go into Dermatology, you might be wondering. Fair enough.) Whatever the reasons, many studies have linked care by an ID specialist to better outcomes. My personal favorite is this one — title says it all: Infectious Diseases Specialty Intervention Is Associated With Decreased Mortality and Lower Healthcare Costs. Talk about a win-win situation. Is there anyone out there who, after hearing that a family member or friend were hospitalized with staph bacteremia, or fever after travel to Malaysia, or spinal osteomyelitis, or bacterial endocarditis, or meningitis/encephalitis, or infection while on rituximab, or newly diagnosed AIDS, would not want an ID doctor involved? ID consultation should be mandatory in all of these cases, for everyone’s benefit.

certification of 140 — 130 won’t cut it, sorry. (If you’re so smart, why didn’t you go into Dermatology, you might be wondering. Fair enough.) Whatever the reasons, many studies have linked care by an ID specialist to better outcomes. My personal favorite is this one — title says it all: Infectious Diseases Specialty Intervention Is Associated With Decreased Mortality and Lower Healthcare Costs. Talk about a win-win situation. Is there anyone out there who, after hearing that a family member or friend were hospitalized with staph bacteremia, or fever after travel to Malaysia, or spinal osteomyelitis, or bacterial endocarditis, or meningitis/encephalitis, or infection while on rituximab, or newly diagnosed AIDS, would not want an ID doctor involved? ID consultation should be mandatory in all of these cases, for everyone’s benefit. - Outbreak control = need for ID doctors. One of my colleagues put it perfectly after helping lead our hospital’s preparation for Ebola last year: “I always dreamed I would have to don a hazmat suit one day.” This is what he wants to do! Whether it’s norovirus infection from a fast food restaurant, listeria in cantaloupes, viral respiratory infections from camels, or Ebola virus disease in Western Africa and beyond, we are front and center in the response to every outbreak — a critical public health role locally, nationally, and internationally.

The above are all reasons — may I be so bold as to say excellent reasons? — why ID has a bright future. And included up there is what I think is an escape from the dollars mess, which is the concluding sentence in the paper cited on the association between ID care and favorable outcomes (bolding is mine):

Patients receiving ID intervention within 2 days of admission had significantly lower 30 day mortality, 30 day readmission, hospital and ICU length of stay, and Medicare charges and payments compared to patients receiving later ID interventions.

It’s up to us to demonstrate that our care improves outcomes and lowers costs, and leverage these data to improve payment for what we do. Ron Nahass, who runs one of the largest ID practices in the country, articulated several approaches in a must-read paper published last year; Eli Perencevich says we should have representation at AMA’s Relative Value Update Committee, which makes tons of sense. I hate to say this in an upcoming election year, but let the lobbying start!

ID is a dynamic, exciting field, and most of us love what we do. When asked if we’d choose our specialty again, we say “Yes!” at a rate way higher than General Internal Medicine, for those weighing a hospitalist position or primary care vs ID.

Yes, ID will survive.

Happy Holidays — and take it away, Wall of Sound!

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UV8x7H3DD8Y]

December 17th, 2015

A Certain Billionaire’s Arrest Prompts Universal Responses — and a Brilliantly Funny One, Too

Several words swiftly come to mind when hearing the news that Turing’s Martin Shkreli was arrested for security fraud.

- Karma.

- Just desserts.

- Kismet.

- Schadenfreude.

- Inevitable.

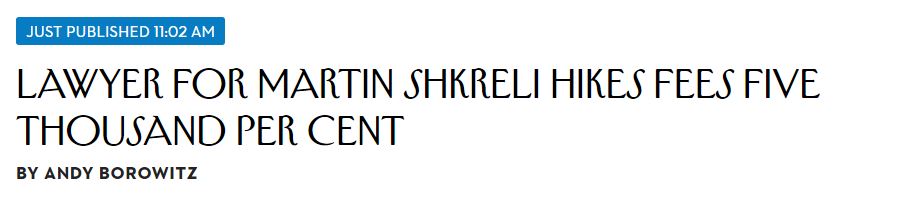

But leave it to Andy Borowitz to get it just right:

Ha, that’s perfect.

Diana Olson from IDSA emailed me “Someone should make a movie …”, which is of course exactly right. What a script: You have the immigrant parent upbringing, the brilliant youth getting into an elite Manhattan high school, then dropping out and starting his “work” on Wall Street at age 20. So far so good.

Then the drug-pricing scandals, his utter refusal to acknowledge wrongdoing, the all-too public face (with a very recognizable smirk) during the controversy, the ubiquitous social media presence, that Wu-Tang Clan album purchase — and now this arrest! Who knows what’s next!

Let the record show that Joel Gallant, in this OFID podcast, was asked “In 10 years, where is Martin Shkreli?” and he presciently responded:

I’d say he’s either going to be in prison or he’s doing a short sale where he’s going to make huge profits off the decline in stock prices of his company and he’ll be on a yacht in the Mediterranean somewhere.

Right now, odds favor the former.

His rise and fall story would be gold, one I’m sure Hollywood will portray with great subtlety. It would certainly have the opposite message of Woody Allen’s later movies, which exist in a random, mostly unjust universe where bad guys often seem to get away with murder. Literally.

So who plays Shkreli in the movie about his life? I vote Bill Hader from Trainwreck — check him out around 1’30” into the clip below, the likeness is truly extraordinary.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2MxnhBPoIx4&w=560&h=315]

And Amy, if you still need a writer, I’m still available.

December 12th, 2015

The 2015 ID Fellowship Match “Historic Bad”: Part 1, Debating the Cause

This year’s ID fellowship match has just taken place, and the results were, ahem, not pretty. Part 1 will cover why we’re in this situation; in Part 2, I’ll offer some reasons for optimism, and even some solutions.

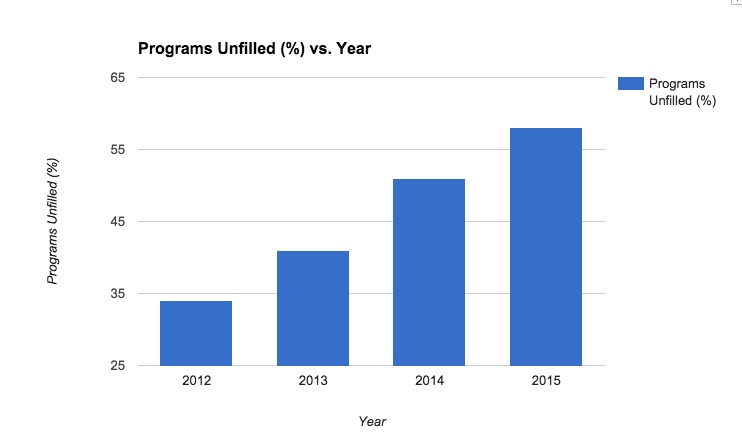

According to data provided by NRMP, 117 of the 335 ID fellowship positions were unfilled. Dan Diekema from U of Iowa, who has written frequently on the issue of the ID match, quickly calculated that over 80% 80 programs had at least one unfilled spot.

[That was an important edit — please see Dan’s comments below.]

When I cited this alarming figure, it generated a spirited email exchange about the ID match with Emory’s Wendy Armstrong, the source of the “historic bad” quote in the title. Wendy is also IDSA Chair of the Task Force for Recruitment to ID, so has thought a lot about this issue.

She acknowledged the trend is worrisome:

The bulk of our exchange, however, was about the reasons for this alarming trend.

Her view: It’s multifactorial: Limited ID teaching in medical school, with declining numbers of dedicated microbiology/ID courses. A significant proportion of preclinical curricula are led by microbiologists alone. ID faculty have less exposure to medical students in the hospital. There are fewer clinical electives for residents. There are fewer ID clinicians acting as attendings on medical services. It’s the money.

My view: It’s the money. At least, it’s mostly the money.

Yes, the factors listed by Wendy are part of it. But since several apply to other medical subspecialties — how many cardiologists or gastroenterologists attend on general medical services? — I’m not sure they are playing much of a role.

Why is the money issue important, and why is it particularly bad for ID? A few thoughts:

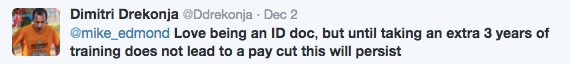

- Debt. Undergraduate medical education in this country is expensive, and a substantial number of doctors in training have significant medical school debt. They look at the 2-3 years of extra training required to become an ID specialist — followed by a lower salary — and cross ID off their list. Or at the very least, strongly consider other options if they are undecided. Or, as put succinctly here:

- The volume/procedure deficit. So long as clinicians are reimbursed primarily based on volume and procedures, ID specialists will be at a disadvantage. Medical complexity and our drive to get the details just right limit the volume part of the equation — you just can’t rush most ID consults, it would be like trying to write a guide to the Louvre after visiting for 30 minutes — and we are not trained to do procedures.

- The “lifestyle” issue. The revenue disadvantage from not doing procedures is shared with other cognitive specialists, of course, but few have so much of their work focused on hospitalized patients. Importantly, nephrology is the other major specialty with declining numbers of applicants, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that nephrology also has plenty of hospital work. Hospital-based specialties require extensive weekend and evening call for urgent cases — cases you have to come in and see, not manage from home. Here’s a comment on my wife’s primary care listserv discussing the 2015 ID match:

ID doctors are always the ones at the hospital late at night working at our hospital. And not compensated for it they way they should be. Many are of retirement age. Only a few younger guys.

Could it be that potential applicants see ID doctors staying late in the hospital, coming in during the weekends and holidays, and wonder — why should I do that and get paid so (comparatively) poorly? The contrast with cardiology, gastroenterology, and intensivist doctors from a reimbursement perspective is obvious.

- Primary care subsidies. Primary care providers are also on the low end of the salary scale, but they rarely do extra years of training after residency. Furthermore, primary care practices may be subsidized, both explicitly through the ACA and as a way of large healthcare systems increasing the number of “covered lives”. Again, from the listserv:

I worked in HIV clinic in urban city in NJ and couldn’t believe what a new grad starts at…one did his fellowship at our hospital and was offered $85k in a private practice and the other was offered $110 as a assistant director so a lot of administrative, teaching, and research in addition to seeing patients. He had to moonlight in the prison system just to make his student loan payment!

Certainly here in Boston, and anecdotally elsewhere, PCPs start at a significantly higher salary than ID doctors.

- The rise in hospitalist positions. The winners in this race to a “real salary” in Internal Medicine? It’s the hospitalists, whose salaries generally exceed those of many ID doctors who have been in practice for years. It’s no wonder that many ID applicants today have spent at least a year after residency as a hospitalist, essentially extending their residency in terms of clinical activity, but now getting paid a whole lot more. How many of these hospitalists once considered ID training, but decided ultimately it wasn’t worth it? Longer hours for less pay, no thanks!

- Biology. In my highly unscientific poll of friends and colleagues, the period at the end of residency is the most common time for doctors to start thinking seriously about starting a family — or, in some cases, actually having babies. Such a major change certainly brings the debt, salary, and lifestyle issues cited above into stark focus.

Reading the above, you might think I’m pessimistic about the future of our speciality, but — call me crazy — in fact the opposite is true. Having one dominant cause to the problem is in many ways easier than a highly complex, multifactorial situation. Fix the money problem, and the interest in ID will rebound nicely.

In Part 2, I’ll try to justify my optimism.

Here’s a relevant 80s classic:

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pp4suZ4jNXg&w=420&h=315]

December 6th, 2015

Do Electronic Health Records Make You a Better (or Worse) Clinician?

Earlier this week, JAMA Internal Medicine published a study entitled, “Level of Computer Use in Clinical Encounters Associated with Patient Satisfaction”.

A more descriptive title would have been “More Computer Use in Clinical Encounters Associated with Reduced Patient Satisfaction”, as here’s the take home point:

High computer use by clinicians in safety-net clinics was associated with lower patient satisfaction and observable communication differences … Concurrent computer use may inhibit authentic engagement, and multitasking clinicians may miss openings for deeper connection with their patients.

As I’ve mentioned before (probably more times than you’d like), the computer’s power to grab our eyes away from our patients is one of the things I like least about EHRs. Of course people are less satisfied with their care when their doctor spends tons of time typing away at the keyboard and looking at the glowing screen.

(Brief aside: Some clinicians mention triangulating the encounter by having both patient and doctor review information from the EHR together. Yes you can do this sometimes, but this tactic really doesn’t work when taking a detailed history. Plus, it’s a capitulation — the computer is now the center of attention, not the patient. Finally, it’s all but impossible to pull this off in many exam rooms, especially those originally designed with no computer in mind. You’d practically have to ask your patient sit on a step-stool or hang from a trapeze over your shoulder to make this work. Not such a brief aside after all, I guess.)

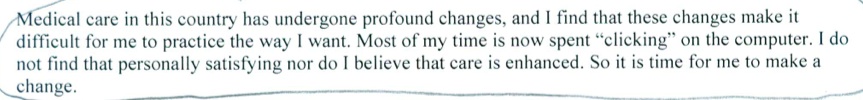

I’m bringing this difficult situation up again not solely because of the published study — similar findings have been reported before. This feeling of being trapped by EHRs is not just an issue for patient satisfaction, but clinician happiness as well. One of my colleagues received a letter from her PCP, informing her that she (an experienced internist) planned to retire. It included this paragraph, which I’m sharing with that doctor’s permission:

So it’s not just the patients who don’t like it — we clinicians aren’t too thrilled either. This internist is hardly the first to complain about becoming a click-slave, though she’s the first I know to use this venue (a letter to patients) to express her opinion.

But the EHR must be good for some things, right?

Of course — a short but not all-inclusive list of the benefits could include trending of lab results, bringing up previous medication histories, displaying radiology images, reviewing other clinicians’ notes, issuing reminders about health maintenance tasks, and receiving warnings about dosing errors, allergies, and drug-drug interactions. Access to records remotely is a huge bonus.

Note I’m deliberately excluding the billing and medicolegal features, as frankly they are usually irrelevant to quality patient care. They are part of EHRs for other reasons. See here for what I think of that “functionality” (a word which always makes me cringe).

All of which makes me wonder — do EHRs make us better at what we do? Or worse?

Help please.

And just in case you missed it …

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xB_tSFJsjsw&w=560&h=315]

November 29th, 2015

Flu Vaccine Keeps Taking Hits, Still the Best We’ve Got — Don’t Stop “Belivin'” [sic]

For reasons understood only by the geniuses in Mountain View, CA, for some reason my Google news feed picked up this bit of “scientific” reporting:

Let me allow the author, an unfortunately named “Clapway” (gonorrhea researcher?), to speak for him/herself:

However, is the flu vaccine really worth it? The author of this article never takes it and has not had the flu in years, knock on wood. There have also been various stories around the web that have stated that people who get the vaccine, immediately get the flu. It then has to be considered that the flu vaccine can be risky to take.

Is this an Onion parody? Or did Google stumble on a Junior High School science/tech blog? If so, a brief word of advice to the author — always double-check spelling (especially the title) before posting.

Admittedly, the recent news on the flu vaccine hasn’t been great — a rehash of reduced effectiveness from repeated immunizations (data are from a study published last year), how poorly the vaccine protects against H3N2, and a study suggesting that statins reduce vaccine efficacy. Of course people taking statins (cardiovascular risk, older) are exactly the people we want to get the vaccine!

On the good news front, we have yet another FDA-approved flu vaccine, this one with the wonderfully named adjuvant squalene to boost immune response. And boy does this new vaccine have a strange-looking brand name — “Fluad.” Good grief. Add it to the zillions of other flu vaccines available — just choose one!

Other good news: This year’s vaccine seems to match the circulating flu virus much better than last year. Cautious optimism.

So warts notwithstanding, until the “universal” flu vaccine is available, the current annual vaccine (in all its various permutations) is the best we’ve got. Even during last year’s dismal performance, there’s some evidence it prevented flu-related illness severe enough to cause hospitalization.

Wise words here from ID colleague Dr. Larry Madoff, who is Director of Epidemiology and Immunization at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Good enough for me.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VcjzHMhBtf0&w=420&h=315]