An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

March 15th, 2016

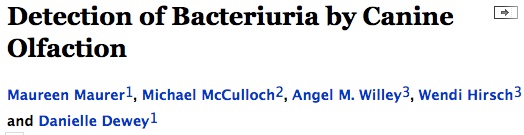

Dogs Again Are Brilliant Diagnosticians

The reputation of dogs in the ID world got a big boost when Dutch researchers published this remarkable study of Cliff — a beagle who was trained to “diagnose” C diff using his superior olfactory abilities.

(A couple of entertaining videos here, if you can’t get enough of this stuff. I can’t.)

Now, in the pages of Open Forum Infectious Diseases (IDSA’s open access journal, of which I’m editor), we’ve published another landmark study demonstrating the extraordinary sniffing powers of our best friends:

From the paper:

In this double-blinded case-control validation study, we obtained fresh urine samples daily in a consecutive case series over 16 weeks. Dogs were trained to distinguish urine samples that were culture-positive for bacteriuria from those of culture-negative controls, using reward-based clicker/treat methods …Dogs detected urine samples positive for 100,000 cfu/mL E. coli (N=250 trials; sensitivity 99.6%, specificity 91.5%).

Impressive! Not only that, but the pooches did equally well with other bacteria — Klebsiella, enterococcus, Staph aureus. An anecdote in the Discussion section of the paper highlighted the real-world performance of Abe (he’s a dog) when a sick person visited the training center — I encourage you to read the full paper (which is on OFID’s early access page) for the details. Not only that, but there’s an action shot of the experimental methods.

So how do the dogs do so well at this task? To start, it is estimated that a dog’s nose is over 100,000 times more sensitive than ours. Plus, there’s this astute comment from my Twitter feed:

Indeed, this diagnostic task is right in the “sweet spot”, as it were, of a dog’s abilities. As the paper notes, “Sniffing urine is innate behavior in dogs.”

Practice makes perfect. Woof!

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L4o68eyT26w]

March 9th, 2016

Approval of TAF/FTC/RPV, Another Single Pill HIV Treatment Option

The approval last week of TAF/FTC/RPV — that’s coformulated tenofovir alafenamide, emtricitabine, and rilpivirine — brings us another one-pill, once-daily option for HIV treatment.

The approval last week of TAF/FTC/RPV — that’s coformulated tenofovir alafenamide, emtricitabine, and rilpivirine — brings us another one-pill, once-daily option for HIV treatment.

It’s essentially the same as the existing TDF/FTC/RPV, with similar pros/cons, but with three notable differences coming with the substitution of TAF for TDF.

Specifically:

- Likely reduced renal and bone toxicity. Since approval was based on bioequivalnce, this hasn’t (yet) been proven in clinical trials — switch-studies are ongoing, comparing TAF/FTC/RPV to both TDF/FTC/RPV, and TDF/FTC/EFV. Note that this might end up being a more relevant consideration with TDF/FTC/RPV than TDF/FTC/EFV, since the former is taken with food and hence leads to higher tenofovir levels.

- A smaller tablet size. TDF/FTC/RPV was already the smallest coformulated pill for complete HIV treatment, and with 25 mg of TAF replacing 300 mg of TDF, the new pill is quite a bit smaller. For some patients, this matters a lot.

- A weird new brand name. It’s called Odefsey, which sounds kind of like the famous Stanley Kubrick film, without the “2001: A Space …”

We can assume (for now) that carried over from TDF/FTC/RPV is the generally well-tolerated profile (low risk of rash, GI side effects, metabolic abnormalities). As with TDF/FTC/RPV, TAF/FTC/RPV should be taken with food and without concomitant PPIs to maximize RPV absorption. It is not intended for treatment-naive patients who have HIV RNA > 100,000 copies/mL.

So this is a nice advance, especially for those patients at risk for renal and/or bone disease. Little reason not to switch existing TDF/FTC/RPV-treated patients to this new formulation, at least once payers add it to their formularies. (As with ECF-TAF, the listed price of TAF/FTC/RPV is the same as TDF/FTC/RPV.)

Note that arguably a bigger TAF-related approval — the TAF/FTC pill, already nicknamed “TAF-ada” — is expected next month.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KliLsBSo-J4]

February 28th, 2016

Really Rapid Review — CROI 2016, Boston

The Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) returned to Boston last week, bringing together over 4000 HIV researchers and clinicians from all over the world.

And note I put “researchers” first — this is certainly the only conference I attend where we are asked to list published papers as part of the registration process! You can almost imagine the program committee reviewing the papers we enter, calculating impact factor and counting first- and last-author contributions.

(I don’t think they really do this. At least I hope not.)

Challenging registration process notwithstanding, the conference organizers are to be credited with releasing the dates of CROI way in advance, greatly facilitating academic and vacation calendars. As the graphic shows, it will be in Seattle next February, back in Boston the following year.

Here is a carefully curated (I’m joking) list of highlights, a Really Rapid Review™ roughly divided into epidemiology/prevention, treatment, complications, cure — and coffee.

- In the United States, the CDC projects that the lifetime risk of acquiring HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) is 1 in 2 for blacks, 1 in 4 Hispanics, and 1 in 11 for whites. Lots of press for these alarming data. I’m an optimist, so I’m betting the under on these estimates given our advances in HIV prevention (PrEP in particular), and the fact that we now treat everyone with HIV.

- In the iPrEx study, higher TDF/FTC levels on PrEP were associated with declines in renal function. These data, and the expected approval of TAF/FTC next month, of course raise the question about the use of TAF/FTC in PrEP. Since you asked …

- Tissue and blood levels of tenofovir after TAF administration are much lower than with TDF. Understandably, this raises a concern about use of TAF/FTC for PrEP. BUT …

- In an animal model, TAF/FTC protected 6 macaques from acquiring SIV. These are encouraging data, and suggest we don’t really know the optimal biological correlates of protection with this drug combination. Bottom line: Whether TAF/FTC will work for PrEP in humans remains unknown — and is a big clinical research challenge.

- In this meticulously detailed case report, a person taking PrEP with TDF/FTC acquired a multi-drug resistant strain — 5 TAMS, Y181C, even integrase resistance! This rare event isn’t enough to change policy or practice, but it’s a reminder that no prevention intervention will be 100% effective 100% of the time.

- Maraviroc seems like an ideal prevention drug given its mechanism of action and expected concentrations in relevant “compartments”. However, in this study of MSM, all 5 patients who acquired infection were receiving maraviroc-based PrEP.

- In separate studies (here and here), a dapivirine-impregnated vaginal ring significantly reduced the risk of HIV infection among African women (paper of one of the studies published here) — but the effect was modest. As in other studies, adherence played a key role, and younger women were not protected at all.

- In MSM at low risk for acquiring HIV, injectable cabotegravir was well tolerated (and preferred to oral therapy), but the q12 week injection schedule did not reliably achieve desired trough concentrations. One cabotegravir subject acquired HIV; trough concentrations were low. A q8 week schedule for PrEP seems likely.

- In this Kaiser cohort study, the “survival gap” between those with and without HIV is closing (13 years overall, 8 years if ART is started with CD4 > 500) — and much of the gap is now attributable to modifiable health risk factors, such as smoking.

- On the other side of the HIV treatment spectrum, this ambitious study evaluated the optimal strategy for retaining in care hospitalized HIV patients with addiction — including intensive patient navigation efforts and cash payments for certain desired outcomes (follow-up visits, picking up the antivirals, virologic suppression). The result? Payment “for performance” with the navigation worked — but only during the 6 months of the intervention. By month 12, the outcome of viral suppression was not significantly different in those with incentives from those who received “treatment as usual.”

- In this British Columbia cohort — where they have meticulous records of treatments and test results — HIV drug resistance to NRTIs, NNRTIs, and PIs has significantly declined since 2009, while integrase resistance has increased. The good news: Integrase resistance is still really, really rare.

- In this randomized clinical trial, stable patients taking TDF/FTC who switched to TAF/FTC maintained virologic suppression and experienced improved renal and bone outcomes. As noted above, approval of TAF/FTC is expected soon — and there are a lot of patients receiving this drug combination.

- Injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine given every 4 or 8 weeks maintained virologic suppression as well as oral therapy. Importantly, no resistance was detected in the one patient who experienced virologic failure. Larger studies planned.

- In a reprise of the EARNEST and SECOND LINE study results, patients failing first-line dual NRTI plus NNRTI-based therapy did comparably well with LPV/r plus either RAL or NRTIs — despite having extensive NRTI “resistance”. Note the quotation marks around resistance, that was intentional since obviously there’s plenty of residual activity.

- Related to NRTI resistance — in this cohort of nearly 2000 patients with treatment failure on TDF, FTC or 3TC, and an NNRTI, the rate of tenofovir resistance ranged from 20% (Europe) to 60% (Africa). Use of 3TC (vs FTC) and NVP (vs EFV) were predictors of tenofovir resistance. Note that TAF is in vitro active vs K65R-containing viruses.

- In this clinical cohort in Amsterdam, there was an unexpectedly high rate of discontinuation of dolutegravir (16%), mostly for sleep, GI, and neuropsychiatric complaints.

- By contrast, this cohort study found no increased risk of virologic failure switching from RAL to DTG. This analysis should be repeated looking at switches from boosted PIs to DTG.

- Viral decay in the two-drug pilot trial of DTG + 3TC (PADDLE) was comparable to the three drug arms from the SINGLE and SPRING-2 studies. Another single-arm study of DTG and 3TC is ongoing (ACTG 5353).

- At 48 weeks in this phase 2 study, the NNRTI doravirine was similar to efavirenz, both arms with just under 80% virologic suppression. Despite these relatively low response rates, there was no drug resistance detected in either study arm; CNS side effects were lower with doravirine. Phase 3 studies of DOR ongoing — and yes, the drug will need to be abbreviated “DOR” since “DRV” is taken.

- This long-acting NRTI MK-8591 — and I mean really long acting, with a half-life of 150 hours with oral administration — induced nearly a 2 log decline in HIV RNA at day 7 after a single 10 mg dose. PrEP candidate? Part of an implantable device? Some other “paradigm shifting” treatment?

- In a European cohort, fractures were 3x more common in HIV positive patients than in the non-infected population. Among antivirals, only tenofovir independently increased the risk of fracture. Osteonecrosis was 100X more common; no specific drug exposure could be implicated.

- Most of the bone loss after starting ART occurs early, but in this study, a single dose of zoledronic acid completely blunted this adverse effect. If this bone loss phenomenon is due to immune reconstitution, one could imagine this intervention one day becoming standard of care.

- In the NEAT study comparing DRV/r plus either RAL or TDF/FTC, RAL increased trunk fat more than TDF/FTC. The study used DEXA, so could not determine if this was subcutaneous or visceral fat, or both.

- Compared to placebo, the quadrivalent HPV vaccine in “older” (age 27!) HIV-positive adults did not reduce new HPV infection or improve the course of anal dysplasia (HSIL). Study stopped early for futility.

- In a highly TB-endemic region, patients with a low clinical suspicion of having TB did not benefit from empiric TB treatment. In hindsight, this was kind of a self-fulfilling prophesy.

- There are many “real world” HCV treatment cohorts out there, and thus far most demonstrate outstanding cure rates in clinical practice, comparable to clinical trial results. Here’s another one (from Germany) which shows a 98% SVR12 among those treated for 8 weeks with LDV/SOF.

- In a study of 26 patients with recently acquired HCV (negative HCV antibody within past 6 months), 6 weeks of LDV/SOF cured 20, with 4 virologic failures — 3 relapses, 1 reinfection. The relapses all had HCV RNA > 9 million copies/mL, adding to data that HCV RNA is a critical determinant of optimal treatment duration.

- The ION-4 study of LDV/SOF for HIV/HCV co-infected patients, only 10/335 experienced virologic relapses. Nine (one didn’t participate) were successfully cured with a subsequent 24-week course of LDV/SOF + RBV.

- Treatment of 9 SIV infected macaques with two different TLR7 agonists induced viral blips and in some reduced the SIV reservoir. Most attention-grabbing: two of the monkeys are now off ART for 3-4 months, with no viral rebound. Stay tuned!

- In virologically suppressed patients, romidepsin (a “latency reversing agent”) and an immunologic boost with Vacc-4x adjuvanted with GM-CSF led to a modest decline in HIV DNA (one marker of the viral reservoir). Viral rebound after stopping therapy, however, appeared unaffected.

- This patient with acute leukemia received a stem cell transplant from a CCR5 negative donor, and has no detectable using sensitive assays — sounds like the n=1 case of HIV cure. Importantly, he remains on ART. Weird that this case is also from Germany! Fingers crossed.

- This cohort analysis demonstrated improved survival among French coffee drinkers with HIV/HCV coinfection. I’ll add this to my list of studies demonstrating the health benefits of coffee — a lifelong quest.

- The plenaries/review lectures this year were excellent — including in particular Bruce Walker on cellular immunity, Jerry Friedland on the intersections of HIV, TB, and poverty, Joe Eron on HIV treatment, Grace McComsey on fat, Paddy Mallon on bone, John Brooks on the HIV outbreak in Indiana, and Eric Rubin on Cheetos — I mean TB. (You had to be there.) All are available on the CROI web site here.

A bit of Boston- and venue-specific news. First, the weather was downright balmy, with temperatures one day pushing 60 degrees and thunderstorms (!) one evening. Last year’s record snow? No problem — it melted long ago.

And I happened to chat with someone who works at the Hynes Convention center, who assured me that the WiFi would be better in 2018.

So what did I miss?

February 20th, 2016

Before CROI 2016, Some Boston Pride — Except for One TINY Detail

Arguably the most important scientific conference in HIV, the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) takes place in Boston next week, as it has many times before.

has many times before.

For those expecting hereafter a CROI preview, or anything even vaguely related to Infectious Diseases and/or HIV, you can stop reading right now. Sorry about that — just contact the folks at NEJM Journal Watch, I’m sure they’d be happy to send you a refund for the price you paid to read this post.

I bring up this almost bi-annual February gathering in my home city since having the meeting here gives me a chance to show off the place to my colleagues.

Yes, even in winter, Boston is wonderful — the narrow streets, the blend of old and new architecture, the river and harbor views, the numerous colleges and universities, the wonderful seafood, the cultural diversity, the parks, the museums, the music scene, the Boston accents that Hollywood loves. Sure the weather can be terrible, but it also can be knock-out beautiful, and the contrast makes us appreciate the good weather that much more.

Comedian Steven Wright has said “Everywhere is within walking distance if you have the time“, which is not just an example of his absurdist humor — I think he got the idea for the joke because he grew up here. Geographically small, Boston is remarkably accessible on foot for an American city, a pedestrian’s dream. The city proper is surrounded by densely populated, poetically named, eccentrically pronounced towns with their own distinct character, many of them also worth a visit.

So I love this place. Can’t you tell?

There’s only one small thing, and it’s this: I’m not a fan of any of Boston’s sports teams.

To explain, let’s take the big four individually, starting with (currently) the two toughest.

For the Red Sox, it’s because I grew up in New York, and in those formative years in which fandom is created (roughly ages 9-12, according to one of my favorite baseball writers), I became truly obsessed with baseball and a certain local historic team — a team whose name I will keep off this page so as not to sully the local 9.

Then I moved here just before a light-hitting shortstop hit a memorable 3-run home run in a memorable game that immediately led to his gaining a new middle name. But even if that hadn’t happened, I doubt my allegiance would have shifted — after all, Red Sox fans never switch when they move to New York. Not even Bill De Blasio, and cripes, he’s the Mayor of New York City. These fan things are tenacious.

For the Patriots, it’s because they play football. And I’m not a football fan. Actually, it’s much more than that — I’m an anti-football fan. Where do I begin?

Maybe with the anti-science denials of the NFL about the dangers of head trauma (stealing pages from the tobacco company, always an impressive role model). Or the fact that many of the players who are being chewed up and pummelled for our entertainment are poor, faceless (thanks to the helmets) minorities. Or the way college football distorts the mission of undergraduate institutions, with the schools’ giving many of the players little more than a sham education. Or how the youth game increases the risk of dementia, and should probably be banned. When I see little kids playing youth football, their big helmeted heads perched precariously over their little bodies, I want to shout to their parents, Don’t you know your son’s brains are in there?

OK, that’s enough on football.

For the Celtics and Bruins, it’s much simpler — I don’t really follow those sports. I know that this year in basketball, the Golden State Warriors (they play in California) are having a historically great season, and that hockey is a fast game played on ice, but couldn’t confidently name a single current Celtics or Bruins player. No credit for Larry Bird or Bobby Orr.

Boston is my home — I love it. Just not the sports teams.

(And I say this fully aware that this is the NEW ENGLAND Journal of Medicine Journal Watch, and the MASSACHUSETTS Medical Society publishing this thing. Oh well. Not surprisingly, some of my very best friends are passionate Red Sox and Patriots fans.)

Back to ID/HIV next week, I promise.

February 13th, 2016

“Choosing Wisely” in HIV Medicine — Sensible (But Safe) Suggestions

The American Board of Internal Medicine has a noble program called Choosing Wisely®, which is both trademarked (look, I even included the “®”), and pretty darn sensible — it has the goal of “advancing a national dialogue on avoiding wasteful or unnecessary medical tests, treatments and procedures.”

The American Board of Internal Medicine has a noble program called Choosing Wisely®, which is both trademarked (look, I even included the “®”), and pretty darn sensible — it has the goal of “advancing a national dialogue on avoiding wasteful or unnecessary medical tests, treatments and procedures.”

If you clicked on the above link, you’ll be taken to the web site, which, in addition to having the obligatory stock photos of earnest doctor-looking people talking to earnest patient-looking people (hey, I have access to some of these too!), also has the specific “Choosing Wisely®” suggestions drawn from various professional societies.

Not surprisingly, all are logical, evidence-driven, and wise. Searching for the term “back pain” brings up 11 recommendations to avoid unnecessary tests and treatments. These range from the simple “Don’t obtain imaging studies in patients with non-specific low back pain” to “Avoid lumbar spine imaging in the emergency department for adults with non-traumatic back pain unless the patient has severe or progressive neurologic deficits or is suspected of having a serious underlying condition (such as vertebral infection, cauda equina syndrome, or cancer with bony metastasis).”

You get the idea. There’s a ton of back pain out there, and we get way too many spine imaging tests. There are so many unnecessary spine MRIs done in the United States that it’s surprising our population doesn’t have its own magnetic force, pulling nearby metallic objects toward our lower backs. So we should be “Choosing [more] Wisely®” when to do them.

The HIV Medical Association just weighed in, and came up with 5 overused tests, all quite logical.

- Avoid unnecessary CD4 cell counts.

- Don’t order complex lymphocyte panels when ordering CD4 counts.

- Avoid quarterly viral load testing of patients who have durable viral suppression, unless clinically indicated.

- Don’t routinely test for CMV IgG in HIV-infected patients who have a high likelihood of being infected with CMV.

- Don’t routinely order testing for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency for patients who are not predisposed due to race/ethnicity.

Good choices, all.

But you might also find that the recommendations are kind of safe, low hanging fruit on the tree of wasteful tests. Furthermore, items #4 and #5, while certainly wasteful (ok, practically useless), are hardly budget-busting diagnostic or therapeutic black holes (to start a new metaphor). These blood tests cost around $50 each; an MRI $2000-3000. And the blood tests are only done once, at the time of a new HIV diagnosis.

In other words, when the policy wonks start talking about rising costs and waste in our healthcare system, they will not be citing G6PD testing in HIV patients.

I shared this opinion with my friend Joel Gallant — because this list sounded just like him — and he confessed that he had a role in its creation “as part of a committee”. (I bet he wrote the whole thing).

I also offered up a few bolder suggestions for avoiding wasteful tests or treatments in HIV care, and he wrote back the following:

We had to be careful not to go against any guidelines.

But if we didn’t have that limitation, anything that you would list? Guidelines- concordant or not?

I’ve got a few ideas, would love to hear yours.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AotDqbCXJes&w=560&h=315]

(H/T to the other Joel — Joel M — for the video.)

February 7th, 2016

Twelve Zika Questions, One ID Doctor’s Answers (Sort Of)

Got a Zika question? Welcome to the club — once again, as with any “new” or “emerging” infection, this is uncharted territory, and there are plenty of answers to these questions that could be summarized with 3 words: We Don’t Know.

Got a Zika question? Welcome to the club — once again, as with any “new” or “emerging” infection, this is uncharted territory, and there are plenty of answers to these questions that could be summarized with 3 words: We Don’t Know.

But never mind that — ever-intrepid ID doctors are most assuredly called upon as experts, even though for obvious reasons the overwhelming majority of us have never seen a case. Remember this outbreak from 2014? The time from first description of an infectious outbreak to the widespread demand for information is fast. People (patients, doctors, the vast public) have questions, and we need to try and answer them. For the record, with Zika, the obstetricians are in the same boat.

In that spirit, I thought I’d share some of the more common or challenging questions I’ve received on Zika, along with my best efforts at answering them. These answers may well be out of date soon, so I enthusiastically refer you to the outstanding Zika coverage on the CDC site, which is being updated regularly.

- I’m pregnant or know someone who’s pregnant. Can I/she travel to — [insert country close to one of the countries that has Zika transmission, but is not currently listed]? Yes … but … with a caveat. It’s a highly dynamic situation, and just like dengue and chikungunya, Zika is likely to be reported in many of these adjacent countries soon (especially in the Caribbean). Not only that, incidence frequently rises quickly in countries after they first report the disease. So why not change those travel plans if possible?

- I’m pregnant or know someone who’s pregnant. Can I/she travel to Florida (or Alabama or Mississippi or Louisiana or Texas or Hawaii)? Yes. There has been no mosquito-borne Zika transmission in the USA yet, though likely there will be sporadic cases soon. But just like dengue and chikungunya, it seems that a widespread outbreak is unlikely — we have more resources for mosquito control, and way more air conditioning.

- How long after returning from [insert Zika country here] can someone safely get pregnant? After all, since 80% of people who get it are asymptomatic, how does one know if Zika infection even occurred? We don’t know the precise duration of viremia for Zika, or whether the duration of viremia correlates with symptoms. (My gut feeling is that it will, but who knows.) Estimates are that viremia clears on average in about a week. So right now it seems prudent to wait at least a couple of weeks after returning before trying to get pregnant, maybe a month to be on the safe side.

- A guy travelled to [insert Zika location here]. How long after travel should he wait before having sex with his pregnant partner? We don’t know how long Zika virus remains in semen after infection, nor (again) whether this duration correlates with symptomatic infection (again, my guess is that it does). Since Zika acquisition during pregnancy is what we’re trying to avoid, these guidelines recommend abstinence or condom use during the pregnancy, which makes sense to me. Now what about the more common scenario, partner isn’t pregnant? Next question, please.

- A guy travelled to [insert Zika location here]. How long after travel should he wait before having sex with his non-pregnant partner? The guidelines linked in the previous question state that these couples “might consider abstaining from sexual activity or using condoms consistently and correctly during sex,” but no duration for this “safe sex” practice is given. Note the use of the word, “might” — this is CDC parlance for, “Look, we’re not going to tell you that doing nothing is totally safe, but we don’t feel that strongly about this recommendation.” (Check out the rabies guidelines for plenty of “mights” in this mode.) After all, Zika infection is pretty mild, and there have only been 2 documented sexual transmissions. In fact, one could argue that if other forms of contraception are being used, that transmitting the infection would have a benefit — namely, immunity for a future pregnancy. For worried folks, I’ve been saying they “might” as well wait a month. For unworried folks, I’m not saying anything. Importantly, there is no evidence that prior infection with Zika will have a negative impact on future pregnancies, once the infection clears.

- Can’t the woman who wants to get pregnant — or even the guy with the pregnant partner — just get a Zika blood test when they return from a Zika country/region, and find out if they were infected? That would make us all less anxious. Not yet. Zika testing is now done mostly through CDC (someone from Florida told me they had local access to testing), and there isn’t the capacity to test everyone. This is why testing is now recommended only for pregnant women who were in Zika transmission areas. Initially it was recommended only for women with symptoms; this was broadened last week to include all pregnant women, even those without symptoms. And remember, the test isn’t so great — there is extensive cross-reactivity with dengue and prior Yellow fever vaccination. So while it would be ideal to have a widely available, rapid, and accurate Zika test, our current test misses on all these marks. I suspect (hope) this will improve shortly.

- I read a vaccine is in the works. When will it be available? Vaccines take years to develop, and many, many millions of dollars. While some have stated that it should be technically feasible to produce a Zika vaccine, that doesn’t mean it will work in humans, or even that if one does work, that it will be marketed. So put this one on the way back burner (unless you’re a vaccine researcher).

- The virus was discovered decades ago. Why hasn’t the link to microcephaly been reported before? A couple of theories, not mutually exclusive: 1) It is likely that in areas where Zika is already established, initial infections predominantly occur during the pre-childbearing years, which induces immunity. 2) The incidence of an infection is often highest after infections enter a community for the first time, as the pathogen encounters a large pool of susceptible hosts. In areas with established infection, the combination of some regional immunity and lower incidence means that fewer women acquire the infection during pregnancy — making it much harder to identify an association.

- I read that some countries with Zika transmission are recommending that women delay pregnancy — isn’t the virus still going to be around for years to come, maybe indefinitely? They can’t be expected to delay having babies indefinitely. This is a controversial recommendation, and indeed the WHO does not endorse it. However, it makes some sense, largely for the reasons cited in the previous question — the delay could allow immunity-inducing infection to occur in some non-pregnant women of childbearing age. Even if this doesn’t happen, the incidence of infection should be sharply lower once a substantial fraction of the population has been infected.

- How do we know that Zika even causes microcephaly? I’m a skeptic. It’s true that we don’t know definitively that Zika causes microcephaly. And it’s highly likely that reporting bias has to at least some degree increased the number of cases, especially in Brazil. But the number of cases reported in Zika-transmission countries is many fold higher than usual, beyond what public health officials would consider solely the result of reporting bias — read this excellent piece in the New York Times, which conveys vividly what was happening as the epidemic accelerated. Lending further support to the connection, researchers have isolated the virus from babies with microcephaly, and there are now reports that French Polynesia may well have had an increase in CNS abnormalities in babies around the time that their Zika outbreak occurred in 2014. Finally, one needs to consider the source of the travel advice — our CDC is very cautious about issuing such travel warnings (substantial geopolitical and economic consequences), and would not make this recommendation unless the evidence were very strong.

- How about Zika and the Guillain-Barré syndrome syndrome? Though there have been reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome after Zika virus infection, whether Zika causes this neurologic syndrome is not conclusively established — more research is needed here, though again the anecdotal data are suggestive. There are, of course, other infections linked to Guillain-Barré, most notably campylobacter, so the association is plausible.

- I hear the virus can be transmitted not just by Aedes aegypti, but also the much more widespread Aedes albopictus. Isn’t it just a matter of time before this virus is charging through the United States like it is through Central and South America? With the important upfront caveat that prognostications on disease spread are notoriously iffy, experts in vector-borne illnesses do not think that this scenario is likely — related to the lower “efficiency” of viral transmission from Aedes albopictus, and the experiences to date with dengue and chikungunya. But sure, there will always be worst-case scenarios — and noisy champions of these views who get lots of attention.

You ID doctors and obstetricians out there — any other questions you’re getting? And from anyone, feel free to offer corrections, insights, other queries, or whatever general thoughts you have in the comments section below.

Hey, isn’t there a “football” game on later today?

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sD_8prYOxo]

January 29th, 2016

Elbasvir/Grazoprevir Combination Pill for HCV a Welcome New Option — With a Few Buts

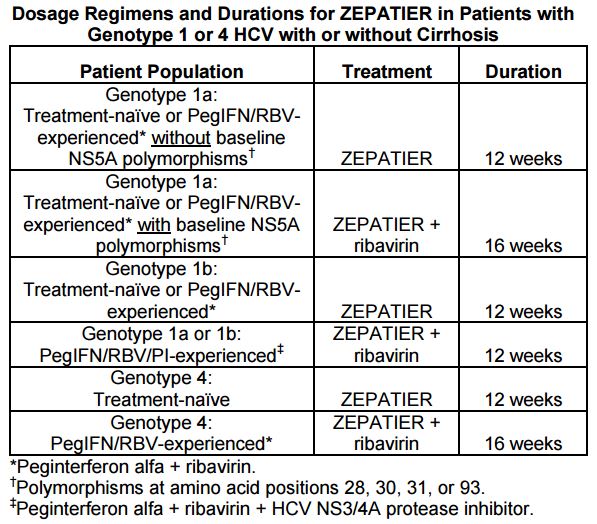

As expected, there’s a new option for HCV therapy, the combination pill elbasvir/grazoprevir (EBR/GZR, brand name Zepatier, more on this below), and it’s indicated for genotypes 1 and 4. For those mechanistically inclined, elbasvir is an NS5A inhibitor (like ledipasvir), and grazoprevir is a protease inhibitor (like simeprevir).

As expected, there’s a new option for HCV therapy, the combination pill elbasvir/grazoprevir (EBR/GZR, brand name Zepatier, more on this below), and it’s indicated for genotypes 1 and 4. For those mechanistically inclined, elbasvir is an NS5A inhibitor (like ledipasvir), and grazoprevir is a protease inhibitor (like simeprevir).

This is the second one-pill, once a day option for HCV, and unlike the first (ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or LDV/SOF), it can be used in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis — an advantage that granted the regimen a “breakthrough therapy” designation, speeding FDA approval.

In addition, the list price is substantially lower — $54,000 for 12 weeks of EBR/GZR, vs $94,000 for LDV/SOF. Of course the actual price paid by government and private payers is heavily negotiated, so how the two will compare remains to be seen. And some providers are treating their low viral load genotype 1 patients with just 8 weeks of LDV/SOF therapy, bringing the price much closer to $54,000 (at least in those cases).

But why the lower price? After all, cure rates are outstanding (94-97% for genotype 1), side effect rates low, and you can’t get simpler than one pill a day.

Seems to me there are two major reasons:

- They’re not the first. LDV/SOF has been available for over a year, and providers are incredibly comfortable with it. Plus, you can barely take a walk down the street, turn on the radio in your car, or flip on the TV without encountering a direct-to-patient advertisement for LDV/SOF. This lower price will be an important strategy for convincing providers, patients, and payers that EBR/GZP is an option.

- It’s not quite as convenient as LDV/SOF. A patient starting HCV with EBR/GZR is somewhat less likely to be taking just one pill a day for 12 weeks than if treated with LDV/SOF.

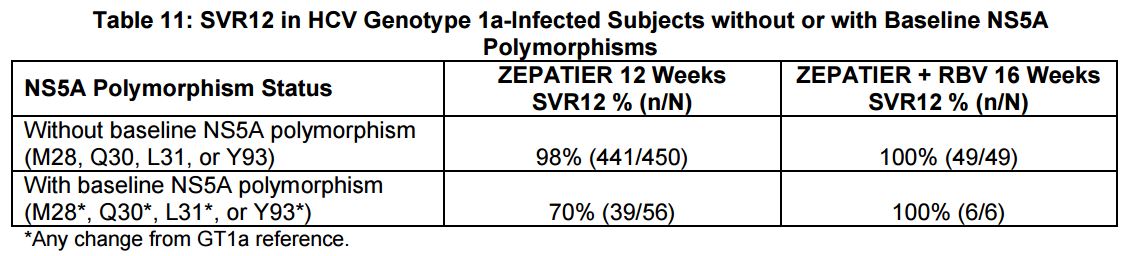

The reason for this slightly greater complexity is that one of the predictors of treatment failure in studies of EBR/GZR was the pre-treatment presence of certain NS5A polymorphisms — which are similar to resistance mutations:

Providers will need to do a pre-treatment test for these polymorphisms. Based on these results and the treatment history, here are the treatment recommendations for the EBR/GZR regimen:

And how common are the polymorphisms? Per the package insert, “The prevalence of polymorphisms at any of these positions in genotype 1a-infected subjects was 11% (62/561) overall, and 12% (37/309) specifically for subjects in the U.S. across Phase 2 and Phase 3 clinical trials …”

Furthermore, as noted above, some of the regimens will also need to be extended to 16 weeks, and the prescribing information recommends LFT monitoring during treatment for all patients. Drug-drug interactions are also more common than with LDV/SOF.

These issues notwithstanding, EBR/GZR is a simpler treatment than the “PrOD” regimen (paritaprevir, ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir) — and for the record less expensive than that one, too.

Not only that, the brand name (Zepatier!) offers a nice French souffle to our existing Italian baked pasta with cheese (Harvoni!).

January 27th, 2016

Here’s an Idea: Justify Your Specialty’s (Low) Relative Salary Using Moral Superiority

In an otherwise excellent piece on recruitment to the ID field from the pages of Infectious Diseases News, comes this:

But while inadequate compensation [for ID doctors] may hamper recruitment, it also could prove beneficial to some degree … Reduced salaries filter out the less-passionate applicants in favor of those who are more dedicated to their patients and to research within the field … “People obviously don’t go into infectious disease as a get-rich-quick scheme … Let’s say the infectious disease reimbursement was double what it is now. There undoubtedly would be more people electing to go into infectious disease, but are they the kind of people we want? I won’t answer that question, but it is certainly something to think about.”

Good grief.

Now look — I understand that money shouldn’t be the primary motivation for a career choice. And furthermore, I’m in total agreement that when some lofty celebrity, athlete, or executive chooses a suspect path based on what appear to be solely financial incentives, it’s reasonable to question the wisdom of their decision.

But are we really ready to justify low ID reimbursement as a way of drawing the most committed doctors to the field?

If so, then let’s cut the salaries even further! Let’s see if I’ve got the math right, using the example above only going in the opposite direction:

Low salaries for ID doctors → More dedication to the field.

Cut salaries 50% → Double how dedicated ID doctors are to what they do.

Result: A 2X stronger pool of ID docs.

This is nonsense, of course.

In the current reality of heavy medical school debts, other subspecialty options, subsidized hospitalist salaries, and the need for extra years of fellowship training, it stands to reason that lower paid specialties such as ID are going to suffer.

No sense justifying this pay gap by some unsubstantiated claim of moral superiority.

Instead, we should be aggressively lobbying that what ID docs do — which is improve patient outcomes, manage complex cases, support other clinicians, deal with public health emergencies, establish protocols and policies, and reduce unnecessary costs — brings value to the healthcare system, and be dutifully acknowledged. Read here for more.

Thank you.

The following video has nothing to do with the above rant, but sure is amazing.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vdTrr_VRKgU&w=560&h=315]

January 18th, 2016

IV and Injectable HIV Treatments Are Much Discussed — But Won’t Be Here Anytime Soon

Something interesting happens when you poll people who treat HIV — and people who have HIV — about whether they’d prefer a treatment option that consists of a periodic injection or infusion in place of the pill or pills that they take every day.

Something interesting happens when you poll people who treat HIV — and people who have HIV — about whether they’d prefer a treatment option that consists of a periodic injection or infusion in place of the pill or pills that they take every day.

Lots of them say yes. Even people who are taking just one pill a day, and are having no side effects.

As a famous comedian (repeatedly) says, What’s the deal with that?

Given the success of currently available oral therapies — in which essentially 100% of people who take it are virologically suppressed — why do so many people say they want shots instead?

Part of it, of course, is the way the question is framed, and human nature. There’s a tendency to favor the shiney new toy. Here’s a typical headline on this topic:

And the simple question — “Would you prefer a shot over pills?” — implies an optimal available strategy. Let’s imagine a single shot administered quarterly, with a small required volume, low rates of injection site reactions, few side effects, and plenty of forgiveness around missed doses. Now we’re talking!

The reason I bring this up is because a couple of recent studies show that non-pill treatments for HIV are at the very least feasible.

Most promisingly, there’s the LATTE-2 study of the long-acting antivirals cabotegravir and rilpivirine — given as injections either every 4 or every 8 weeks — which maintained virologic suppression as well as a standard 3 drug regimen. (More details expected soon.)

And there’s this study of the broadly neutralizing antibody VRC01, which when infused to patients with viremia, dropped HIV RNA 1.1-1.8 log (10-100 fold) in 6 of 8 with a single infusion. It follows an earlier study showing an even more potent antiviral response using a different antibody, 3BNC117. Both treatments dropped HIV RNA long after the single dose.

So we’re on our way, right? Soon we’ll be offering injections or infusions as an alternative to pills, and we’ll all live happily ever after!

But it’s not so simple. Here are a few compelling reasons why we’re not going to see these injectables as viable treatment options in the near future:

- Current treatment is really, really good. Let’s start with the obvious one. Out of 100 newly diagnosed patients, how many can’t get by with one of the Recommended or Alternative DHHS regimens? So the motivation to develop long-acting injectable treatments isn’t quite a life or death matter. “But not everyone can take pills every day,” you say. Indeed that’s true, but …

- Many poorly adherent patients would be lousy candidates for long-acting therapies. This is counterintuitive, as they are the first group one would consider for injectable treatments — people who don’t take their meds now. But to be eligible for cabotegravir plus rilpivirine maintenance therapy, first virologic suppression needs to be achieved — which requires adherence to pills. An oral lead-in is also prudent to screen for acute toxicities that would be very tricky to reverse given the 40-day half-life of injectable cabotegravir. “You’re not getting it back once you inject it,” is what one PharmD memorably said. Finally, what if this non-adherent person decides to be non-adherent to the injections? Misses a few scheduled shots? Takes off for Honduras, as one of my intermittently compliant patient unpredictably does, sometimes with and sometimes without his prescribed ART. Then you have the l – o – n – g tail of low drug levels, which could allow for virologic rebound and selection of resistance.

- So far, it’s not even close to a “simple injection.” It’s not like an insulin shot, or a flu vaccine. The cabotegravir/rilpivirine treatment will almost certainly be at least two intramuscular injections, volume and time between doses to be determined. And monoclonal antibody treatments will likely require an infusion of some sort — time consuming!

- Use of broadly neutralizing antibodies for treatment has many significant hurdles. These “bNAbs” (as they’re cleverly nicknamed) are fascinating scientifically, but will be a bear to get into a practical treatment regimen. Here are a few issues to consider: 1) Some patients have pre-treatment resistance (2 of 8 in the VRC01 study, for example) — will this require a pre-therapy test, akin to viral tropism testing? 2) Treatment selects for escape mutants — in other words, resistance. Combination therapy will be required, perhaps with complimentary bNAbs — will each require a separate pre-therapy test to determine susceptibility? 3) Monoclonal antibody treatments can be antigenic, triggering allergic reactions. 4) If penetration into the CNS is important for at least some component of ART, these monoclonal antibodies aren’t getting there. 5) See above regarding infusion time. All in all, I confess to not quite getting the fascination with bNAbs for treatment, but maybe that’s just me.

- The entire regimen has to be long acting, and preferably also not require pills. If there’s a parenteral therapy that can be given every 2 months, but patients still need to take pills every day to complement the treatment, what’s the point? This is why the cabotegravir/rilpivirine regimen is so far ahead of anything else.

Granted, even as the cabotegravir/rilpivirine treatment is currently configured — a few shots every 8 weeks — there will be a subset of patients for whom this is their preferred way of receiving therapy. Could be cost-effective, too, especially if it’s priced reasonably.

But I’m thinking it’s going to be small group who actually prefer this treatment to a single pill a day. And we’re not going to see it anytime soon.

Pop Tarts, Jerry?

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=itWxXyCfW5s]

January 10th, 2016

Medical Marijuana and Painful Neuropathy — An Opportunity to Make Us Believers

Medical marijuana is now officially available in New York, the city with by far the largest number of people living with HIV/AIDS in the country. Reporting on the first dispensary in Manhattan, the aptly named Julie Weed (yes! her real name!) writes:

Medical marijuana is now officially available in New York, the city with by far the largest number of people living with HIV/AIDS in the country. Reporting on the first dispensary in Manhattan, the aptly named Julie Weed (yes! her real name!) writes:

One of the most promising areas for research is the substitution of medical marijuana for opioids like OxyContin and Percocet for pain management …“68% of our patients with AIDS-related neuropathy have said that medical marijuana has allowed them to stop taking opioid prescription pain killers which can be addictive, cause a variety of harmful side-effects, and — most critically – are the cause of thousands of overdose deaths per year.”

Some thoughts based on this claim, and the long history of medical marijuana and HIV/AIDS:

- Could 68% of patients with painful peripheral neuropathy really stop opioid pain killers with marijuana? Wow. If that’s true, it’s huge — even half this rate would be a dramatic advance. Among the most frustrating conditions in all of medicine, painful peripheral neuropathy has a list of treatments as varied as the products sold in the “Cough and Cold” aisle at your pharmacy — and are, unfortunately, about equally effective. Proven strategies to help people come off chronic narcotics are badly needed.

- HIV specialists have been hearing about the medical use of marijuana even longer than we’ve had effective antiretroviral therapy. Initially touted as an appetite stimulant for HIV-related anorexia and weight loss, and as palliative therapy to ease the pain of death and dying, it gained further use in the mid-1990s when early HIV-related combination regimens caused so much nausea. This randomized clinical trial led by Donald Abrams — who has done some of the best work studying marijuana in HIV against great odds — found that 5 days of smoked cannabis was more effective than placebo in 50 patients with painful peripheral neuropathy. Of course blinding the study arms was (and remains) essentially impossible given the euphoric effects of the drug, but maybe that’s the whole point.

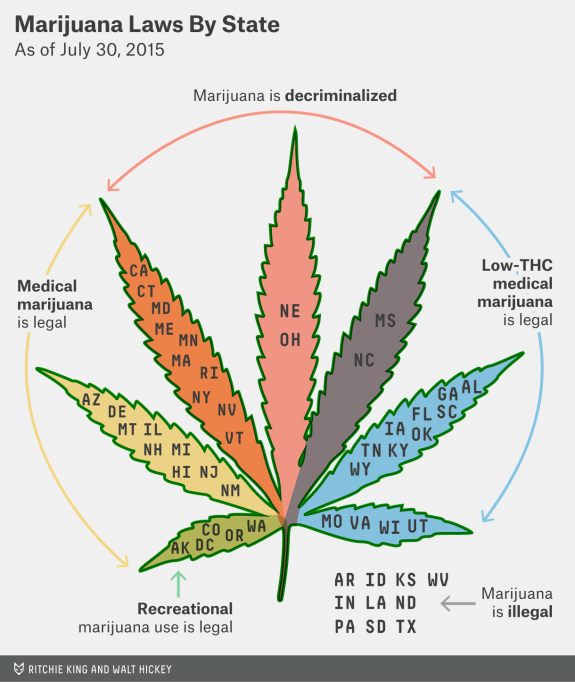

- Just legalize the stuff already. That’s how I’d characterize the opinion on marijuana for the vast majority of the doctors, nurses, and social workers I work with, some of whom (like me) both remember Woodstock (the original one, kids) and enjoy the music from it, or are younger, and have the same view. If marijuana is legalized, it can be more easily regulated, taxed, and studied (see below) — just like that other legal psychoactive drug, alcohol. Seems like this is hardly a minority view (the link is to the source of the graphic at the top of the page).

- Legalization would allow more rigorous studies of therapeutic use, long-term effects, and safety. Such studies are now essentially prohibited by the federal government since marijuana is considered a drug of abuse. As a result, many claims about its medical indications are based on either small, short term, or methodologically questionable studies or, even worse, strongly-held beliefs based mostly on anecdote — the weakest form of scientific evidence. That is, I’m afraid, what that “68% have stopped their opiates” claim is from the opening paragraph. Until it’s studied more rigorously, we’re stuck with the frustration of dealing with claims that marijuana is a valid treatment for practically every chronic condition under the sun. A similar claim might be made of benzodiazepines like Valium, Xanax, and Klonopin — which definitely make people feel better — but clinical research has more clearly defined both the benefits and risks of this drug class.

- The quasi-medical atmosphere of some marijuana dispensaries is a huge negative to the acceptance of legitimate medical use. Got a free 10 minutes? That plus saying you have “insomnia” gets you a weed license for the medical stuff in Venice, no medical records required. Medical marijuana exists in this bizarre parallel system to “real” FDA approved drugs, and the absence of good scientific data means that the indications for use state-by-state are literally and figuratively all over the map. Got to love this indication (and I use the word loosely) for medical use from California: “Any other chronic or persistent medical symptom that substantially limits the ability of the person to conduct one or more major life activities (as defined by the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990) or, if not alleviated, may cause serious harm to the patient’s safety or physical or mental health.” If it’s based on patient report, that covers pretty much anything, doesn’t it?

So what’s my take right now? Count me in the same camp as these authors, who published their views in a JAMA editorial last year, writing:

If the states’ initiative to legalize medical marijuana is merely a veiled step toward allowing access to recreational marijuana, then the medical community should be left out of the process, and instead marijuana should be decriminalized … Evidence justifying marijuana use for various medical conditions will require the conduct of adequately powered, double-blind, randomized, placebo/active controlled clinical trials to test its short- and long-term efficacy and safety. The federal government and states should support medical marijuana research.

Totally agree. Meanwhile, here’s a study design free for the taking:

Title: A randomized, blinded study of cannabis versus placebo to reduce opiate use in HIV-related neuropathic pain.

Entry criteria: Painful HIV-related neuropathy for ≥3 months, confirmed by a neurologist at screening, and requiring the use of opiates for control. Stable doses of opiates for at least 4 weeks prior to screening are required. HIV RNA must be < 50 copies/mL on non-neurotoxic containing ART.

Intervention: Smoked cannabis or placebo for 24 weeks; up to daily use as desired by study subjects. Adjunctive therapies (gabapentin, antiepileptics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acupuncture) will be administered at the discretion of the investigators.

Primary endpoint: Time to cessation of opiate use as estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method.

Secondary endpoints: Time to reduction in 25, 50, and 75% of opiate use; absolute and relative reduction in opiate dose. Proportion opiate free at study completion. And what the hell, might as well also do Numeric Pain Rating Scale, Change in Pain Inventory Score, Numeric Rating Scale Sleep Interference Score, Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale, Patient Global Impression of Change of Pain, and all those other neuropathy assessments. Throw in some neurocognitive testing just for fun.

Funding: National Institutes of Health

You’re welcome!

Let’s see if what you think.