An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

April 22nd, 2018

Some ID Stuff We’re Talking About on Medical Rounds — with Bonus Andy Borowitz Podcast

As an infectious diseases specialist attending on the general medical service each year, I am the beneficiary of a wonderful knowledge exchange.

The smart house staff and my generalist co-attending teach me the latest about hyperkalemia, anticoagulation, anemia, alcohol withdrawal, acute renal injury, COPD, atrial fibrillation, pancreatitis, asthma, diabetes, and congestive heart failure — to name a few of the non-infectious issues that come up routinely during inpatient care.

For example, I am now quite comfortable saying HFpEF — which, if you haven’t done inpatient medicine in a while, is pronounced “HEF-PEF,” and most certainly did not get mentioned a single time during my residency training.

And what do they get in return? A bunch of infectious diseases snippets, factoids, random comments, and (I hope) clinical pearls, such as the following:

- A shorter course of antibiotics should in many conditions become standard of care. In addition to the linked review, two studies at the current ECCMID meeting in Madrid also showed that shorter is just as good as longer — or even better! There’s less drug exposure, less chance for toxicity, and a faster return to usual activities. The studies were: 1) Three versus eight days for community-acquired pneumonia, and 2) Seven versus fourteen days for gram-negative blood stream infections. We will obviously need to see the full details of these studies once published, but it looks like the antibiotic “course” has had its day.

- Guidelines for treatment of uncomplicated lower UTI in women recommend nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or fosfomycin. And hot off the presses — nitrofurantoin for 5 days is better than single dose fosfomycin. Note that quinolones are not included due to concern about “collateral damage,” specifically in this paper their effect on antibiotic susceptibility. See below for an additional concern about quinolones we discussed on rounds this week.

- The guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of C. diff have been updated. Among the highlights: vancomycin or fidaxomicin (not metronidazole) for first-line therapy; vancomycin taper or fidaxomicin for first recurrence (if vancomycin used as initial therapy); for more than one recurrence, vancomycin followed by rifaximin; and for patients with multiple recurrences, referral for fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). There’s also an acknowledgement that nucleic acid testing alone (without the proper clinical correlation) has an unacceptably high false-positive rate.

- The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) now includes the new hepatitis B vaccine. The vaccine (called HepB-CpG or “Heplisav-B”) is indicated for HBV-seronegative individuals over 18. Given as two doses separated by 1 month (rather than three doses over 6 months), HepB-CpG is both easier to give and more immunogenic, yielding protective antibody responses in 90.0%–100.0% of recipients vs. 70.5%–90.2% with the older vaccine. As with the other recently approved “adjuvanted” vaccine for zoster, postmarketing safety data will be important, as will data on its efficacy in prior non-responders.

- The price of linezolid has plummeted — but you’d still better shop around. I’ve mentioned this price drop before — but it’s worth repeating since linezolid was so notoriously expensive for so long that many clinicians might not realize the price has changed. How about fidaxomicin, mentioned above in the C. diff guidelines? No such luck.

- The most important risk factors for cefepime neurotoxicity are older age and decreased renal function. Encephalopathy and delirium, sometimes associated with myoclonus, are the most common manifestations; seizures may rarely occur.

- An interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) is now the preferred test in most settings for latent TB. Tuberculin skin tests (TSTs) continue to be used for “budgetary reasons,” or in the settings where both an IGRA and a TST would be useful. Indications for both IGRA and TST would be a high-risk setting where either test being positive would prompt treatment (e.g., prior to receiving TNF-blockers in a patient from a TB-endemic region), or in a low risk setting where either being negative would mean deferring therapy. Pet peeve: It’s better to say IGRA (“ig-rah”) than either of the brand names. Thank you.

- Doxycycline may have anti-inflammatory activity. This property, independent of its antibacterial effect, is the reason some dermatologists choose very low doses for treatment of acne, and why they sometimes continue it for ulcerative or bullous disease even in the absence of infection. Note that this ancillary effect was not mentioned by Rebeca Plank in our antibiotic draft, even though she chose doxycycline first. Maybe I should get it on a technicality?

- Fluoroquinolones should be avoided for acute sinusitis, acute bronchitis, and uncomplicated urinary tract infections unless there are no other treatment options. The reason — “fluoroquinolone toxicity syndrome,” which consists of “disabling and potentially permanent serious side effects … that can involve the tendons, muscles, joints, nerves, and central nervous system.” This FDA action in 2016 has substantially changed clinical practice, as previously these drugs were used like water — in other words, excessively.

- Dogs have been used to diagnose both C. diff and urinary tract infections. The best part about these papers are the videos (here and here) that cover them! The pictures are cute too (see above).

Meanwhile, in other news, there’s this podcast — highly recommended and entertaining!

https://www.facebook.com/andyborowitz/posts/10156754879150681

And note, not a single mention of an antibiotic.

April 16th, 2018

Hepatitis C Positive Organ Donors — Coming Soon to a Transplant Center Near You

There’s one immutable fact in solid organ transplantation — the number of patients awaiting transplant exceeds the number of available organs.

There’s one immutable fact in solid organ transplantation — the number of patients awaiting transplant exceeds the number of available organs.

This shortage means that ethical, medically safe strategies to increase the donor pool are always a high priority.

One such strategy would be to allow transplants from people who have chronic hepatitis C.

If the thought of transplanting an HCV-infected organ into an uninfected recipient gives you pause, you’re not alone — the practice is explicitly discouraged in some transplant guidelines.

However, HCV today is an entirely different beast than when these guidelines were crafted. Treatment is now astoundingly safe and effective, with over 95% of patients cured, typically with 8–12 weeks of simple therapy.

Not surprisingly, transplant programs are now studying the safety of conducting transplants from HCV-infected donors into HCV-uninfected recipients, then treating with HCV therapy.

While published data are still relatively sparse, two small studies in renal transplant recipients (here and here, 10 patients each), showed that HCV treatment at the time of transplant or shortly after is safe and effective. None of the 20 patients developed chronic hepatitis C.

Now a third study (led by my colleague Ann Woolley), has just been presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation.

In this trial of lung and heart transplant recipients, 33 patients received organs from donors who were HCV viral load positive; an additional 8 came from donors who were HCV antibody positive but viral load negative. The former group received an abbreviated 4-week course of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir right after transplant; the latter only received treatment if they became viremic (none has to date).

With the caveat that the study is ongoing, thus far the the regimen has been well-tolerated, with no one developing chronic HCV.

Not surprisingly, several other hepatitis C donor protocols are starting, but it’s not rocket science to predict their outcomes. HCV can be effectively treated and cured (or prevented, if you interpret preemptive therapy that way) in transplant recipients, with currently available regimens.

Doing so will greatly increase the pool of available organs. In a tragic silver lining to the horrible opiate epidemic cloud over our country, premature deaths from overdoses may provide life-saving organs to patients in desperate need — organs that previously would have been discarded due to hepatitis C. A paper published today shows that the number of donated organs from overdose deaths has already increased 24-fold since the year 2000 — imagine what this increase would be if organs from people with HCV were permitted.

(Sorry about the silver lining cliché there — but at least I’m in good company!)

Are there remaining research questions with this strategy? Of course — among these include selection of the best regimen, the duration of therapy, management of drug interactions, and cost. Plus, we must recognize that these remain high risk donors who may have other infectious diseases (besides HCV) that will influence transplant outcomes.

But these are answerable questions, with none insurmountable. As noted in this excellent editorial, we’ve long allowed transplants from CMV-positive to CMV-negative patients — and the antiviral regimens for CMV are far less safe and effective than those for HCV.

Can’t you see a policy change coming soon?

April 8th, 2018

Latest DHHS Guidelines for Initial HIV Therapy Now Include 5 Choices — But Really 2 Are Best

On March 28, the Department of Health and Human Services Guidelines issued an update to the HIV treatment guidelines, with a focus on the recent approval of bictegravir/TAF/FTC:

On March 28, the Department of Health and Human Services Guidelines issued an update to the HIV treatment guidelines, with a focus on the recent approval of bictegravir/TAF/FTC:

BIC/TAF/FTC is an effective and well-tolerated INSTI-based regimen for initial therapy in adults with HIV, with efficacy that is noninferior to DTG/ABC/3TC and DTG plus TAF/FTC for up to 48 weeks. On the basis of these clinical trial results, the Panel classifies BIC/TAF/FTC as one of the Recommended Initial Regimens for Most Adults with HIV.

Based on this change, there are now five recommended initial regimens for most people:

- Bictegravir/TAF/FTC

- Dolutegravir/ABC/3TC

- Dolutegravir + TAF (or TDF)/FTC

- Elvitegravir/cobicistat/TAF (or TDF)/FTC

- Raltegravir + TAF (or TDF)/FTC

All are based on an integrase inhibitor and a pair of NRTIs. Four have tenofovir/FTC as the NRTI pair. Three are available as a single tablet, once daily.

But with the important caveat that what follows represents my opinion and not that of these or any other guidelines, one could easily argue that there are really two primary choices here, not five.

And those are dolutegravir + TAF (not TDF)/FTC and, now, bictegravir/TAF/FTC.

Here’s why:

- Raltegravir and elvitegravir both have a lower resistance barrier than dolutegravir and bictegravir. Virologic failure with elvitegravir and raltegravir may select for integrase resistance, usually along with NRTI resistance. This hasn’t happened yet in any clinical trial of dolutegravir or bictegravir for initial therapy, at least when given with two NRTIs.

- Elvitegravir requires the pharmacokinetic booster cobicistat. This greatly increases the drug interactions of this option, some of which are highly clinically significant.

- Raltegravir is two pills. In addition, it cannot be coformulated.

- The association between abacavir and cardiovascular disease has become stronger with recent research. In addition, abacavir requires pre-treatment HLA-B5701 testing and does not treat hepatitis B. Furthermore, the coformulation of dolutegravir/ABC/3TC is the largest of the single-pill options for HIV therapy.

- TAF has a better renal and bone safety profile than TDF. There will likely be cost benefits of TDF/FTC over TAF/FTC eventually, but they are not yet realized in the clinic.

As of April 8, 2018 (the day I’m writing this post), the choice between the two remaining options reflects how we and our patients feel about two issues.

If giving one pill rather than two is most important, then go with bictegravir/TAF/FTC.

If accumulated safety and “real world” experience is most important, then go with dolutegravir plus TAF/FTC.

Hey, isn’t HIV treatment simple these days?

April 1st, 2018

News Flash — The World Isn’t Sterile

You might have missed this press release from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID):

Bethesda, MD

April 1, 2018

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, at the National Institutes of Health, invites grant applications which propose research in the following 3 critical world health challenges:

1. Development of an effective HIV vaccine.

2. Global eradication of malaria.

3. Identification of the germs you can find lurking on or inside everyday objects. Priority items for this research include the kitchen drying rack, the shower curtain, and bathtub toys.

Well, not really.

But the inspiration for that (lame) April Fools’ Day joke was this recently published study finding bacteria inside your kid’s rubber duck.

And it’s not just rubber ducks. A prior study found these and other scary bugs in your office coffee maker.

While we’re at it, let’s take a look at your flight’s tray table.

On your kitchen sponge.

Or in the other room, on your TV remote control.

Outside, in the playground sandbox.

And beware your doctor’s necktie and stethoscope. And that white coat? Teeming. I could go on and on.

(In fact, I already did!)

Indeed, if you look hard enough, bacteria can be found literally everywhere — except perhaps inside your hospital’s autoclave.

What’s missing from all these studies, of course, is a correlation between identification of these bugs and any subsequent diseases. It’s not as if kids with rubber ducks are coming down with more infections than kids who don’t have them.

Perhaps a competing bath toy company will fund a clinical outcomes study, but don’t hold your breath. The rubber ducks have quite a stranglehold on this market.

In summary, bacteria on common household, work, and travel items are ubiquitous; furthermore, we lack any clinical data that this is important in any way.

Hence, I wonder — why are these “we found bacteria on [common-item]” studies so common? Even more perplexing, why are they such popular news fodder? The press can’t seem to get enough.

Hence, I wonder — why are these “we found bacteria on [common-item]” studies so common? Even more perplexing, why are they such popular news fodder? The press can’t seem to get enough.

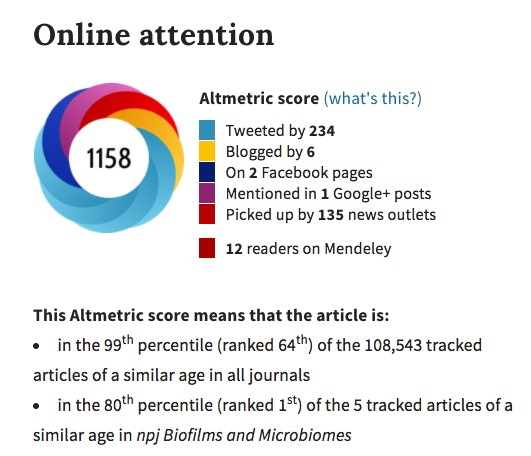

According to its Altmetric score (pictured to the right), the above-mentioned rubber duck study is a bigger news story than the fact that rates of tuberculosis in the USA have reached historic lows.

(Since TB control is one of the few things our crazy U.S. healthcare system does really well, I like to publicize these data whenever possible. You’re welcome.)

And what do we call these studies? Clearly the very category deserves a name:

I need a clever word or phrase to describe this category of study: "We cultured [common household/work/travel item]; here are the [scary sounding microbes] we found."

Suggestions? https://t.co/jSPg8LTi5n— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) April 1, 2018

While there are several excellent proposals, I’m particularly partial to two answers so far — “Quotidiome” and “Ubiquibiota” — and certainly understand the appeal of “Nocarediosis,” though that one might be a bit too obscure for non-ID types.

Any other ideas?

March 25th, 2018

Why Is Some Academic Spam Funnier Than Others?

This invitation made me laugh out loud:

From: International Journal of Poultry and Fisheries Sciences <poultry@symbiosisonline.us>

Date: Friday, March 23, 2018 at 7:03 AM

To: “Sax, Paul Edward,M.D.”

Subject: Accepting Articles for our Inaugural Issue: IJPFSDear Dr. Paul E Sax,

Greetings from International Journal of Poultry and Fisheries Sciences!

We are privileged to introduce International Journal of Poultry and Fisheries Sciences a peer reviewed journal and currently inviting papers for inaugural issue.

We had a glance at your published article “Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, coformulated with elvitegravir, cobicistat, and emtricitabine, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: two randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trials.”.

We found your article very innovative, insightful & interesting; we really value your outstanding Contribution towards Scientific Community and it was really appreciated.

With the theme of ‘Serving Scientific Community for a better Mankind’, to International Journal of Poultry and Fisheries Sciences is publishing articles dealing with all aspects of poultry and fisheries. Being impressed by your quality work, we are contacting you to know if you can associate with us by submitting your upcoming research.

We accept any article (Research Paper, Review Articles, Short Communications, Case Reports, Mini- Review, Opinions, and Letter to Editors etc.) for publication so, we Request you, to provide your manuscript on or before March 29th, 2018.

Note: If need arises, we will extend the date of submission as per your convenience.

Your diligent work and speedy submission will expedite the release of the inaugural issue of the journal.

International Journal of Poultry and Fisheries Sciences would be highly appreciative of your contribution and cooperation.

Thank you for your valuable time! Kindly revert to us for your queries.Best Regards,

Carolyn Sonia

International Journal of Poultry and Fisheries Sciences

Symbiosis Group

This might be the most absurd single item of academic spam I’ve ever received.

Beats the invite from the Johnson Journal of Aquaculture and Research by a mile.

And surpassed everything on this list from Marty Hirsch, which I can’t resist sharing again:

Per Journal of Infectious Diseases Editor-in-Chief Marty Hirsch, a short list of copycat predatory journals over the years — with my personal, all-inclusive favorite highlighted! #academicspam pic.twitter.com/4Xy7VEpDnw

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) December 31, 2017

So congratulations to the “International Journal of Poultry and Fisheries Sciences,” or the “IJPFS,” as it’s commonly known to all — you are the winner!

Which got me wondering — why is some academic spam funnier than others?

March 18th, 2018

Why with Extremely Resistant Infections, It’s Extremely Important to Consult ID

Since the only procedures most of us Infectious Diseases doctors do with any regularity are biopsies of patient medical records, we have to justify our existence in other ways — such as collecting data on how our expertise improves patient outcomes.

Since the only procedures most of us Infectious Diseases doctors do with any regularity are biopsies of patient medical records, we have to justify our existence in other ways — such as collecting data on how our expertise improves patient outcomes.

There are a bunch of these papers published, with this one being the most widely cited (the title says it all):

Infectious Diseases Specialty Intervention Is Associated With Decreased Mortality and Lower Healthcare Costs

Here are a few more, hardly a comprehensive list:

- Staph aureus bacteremia (one of several) — some hospitals mandate ID consultation for this entity

- Infections related to solid organ transplantation

- Cryptococcal infection — as I’ve written before, who would try managing this tricky condition without ID input?

- Endocarditis

- Candidemia

Now, a paper just published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases looks at the effect of ID consultation on outcomes in patients hospitalized with multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs).

The retrospective review spanned nearly 10 years of data and included over 4000 patients. The researchers found that ID consultation was associated with a significant reduction in all-cause mortality for drug-resistant S. aureus, Enterobacteriaceae, and polymicrobial MDRO infections.

For some of these infections, the effect was huge — a 50% decrease in deaths. Patients with resistant gram-negative infections also had a reduction in 30-day readmissions.

Studies like this are critically important to our specialty. They demonstrate the value of Infectious Diseases in ways that go far beyond simply counting “relative value units” (RVUs), a scoring system where we invariably come up short.

Finally, leave it to that bastion of common sense, Consumer Reports, to summarize the results perfectly:

Aside from the hyphen between “infectious-disease” in the subtitle, I couldn’t have said it better myself!

March 11th, 2018

Really Rapid Review — CROI 2018, Boston

The 25th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) just wrapped up in warm, sunny Boston.

The 25th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) just wrapped up in warm, sunny Boston.

Everyone in attendance took advantage of the fine March weather to get some much-needed sun, to feel the sand between their toes, to sip a tropical drink, and to hear the latest in HIV research.

Well, the last part was true — CROI clearly remains our best meeting, the only one that brings together so much high quality research from so many disciplines. Clinical, basic, and behavioral researchers all have a place here.

And though the meeting was bookended by a pair of Nor’easters — the one at the start was a whopper, I thought my dog Louie would blow away in the wind — the weather during most of the conference was actually not bad at all.

On to some highlights, a Really Rapid Review®, with apologies ahead of time for the poor organization. As always, feel free to write in the comments section any important studies I might have missed.

- One-month of daily rifapentine/INH prevented TB as well as 9 months of daily INH [37LB]. First place in this RRR® goes to a TB prevention study — this is also a conference on opportunistic infections, remember? This important randomized clinical trial has the potential to change clinical practice, as clearly a one-month preventive strategy is far easier than a 9-month one. One big question — can we extrapolate to HIV negative people?

- 5 of 11 monkeys treated with both a TLR7 agonist plus a broadly neutralizing antibody did not rebound after stopping ART [73LB]. Not only that, cells from these monkeys (lymph node and PBMCs) did not transmit SHIV to other monkeys in an “adoptive transfer” demonstration of cure (or the closest thing we have to a proof of cure). Very exciting results, with the caveats being that these monkeys were treated with ART within 1-2 weeks of acquiring SHIV, this is SHIV (not HIV), and these are monkeys (not humans).

- No increase in IRIS when raltegravir added to a standard regimen of TDF/FTC/EFV [23]. Data are from the REALITY randomized trial in advanced HIV disease conducted in Africa, and contrast with information from observational studies.

- Twice daily dolutegravir plus two NRTIs is comparable to TDF/FTC EFV in TB/HIV coinfection [33]. The culprit in drug interactions for all these TB studies is rifampin, which voraciously eats many other drugs alive (that is, induces their metabolism). But doubling the dose of dolutegravir here seemed to do the trick. Note again — no increased risk of IRIS with DTG vs EFV, despite the faster virologic suppression.

- TAF/FTC [28LB] likely can be safely administered with rifampin, but bictegravir can’t [34]. More on this theme — in the first study, while rifampin lowered plasma levels, intracellular concentrations of tenofovir diphosphate were higher than with standard dose TDF. Doubling the dose of bictegravir did not overcome the induction of the drug’s metabolism.

- Darunavir/ritonavir plus 3TC is non-inferior to darunavir/ritonavir plus TDF/FTC [489]. Further follow-up of the ANDES study, done in Argentina — think GARDEL, only with DRV/r. Only one patient developed resistance (M184V in triple-therapy arm), and there was no difference in response between high- and low- viral load strata. Study sample size is relatively small (n=145) due to funding limitations.

- For patients starting therapy with HIV RNA > 100,000 and/or CD4 < 200, INSTI- and EFV-based regimens have the lowest risk of treatment failure[493]. Since the risk of dolutegravir resistance in treatment-naive patients is so low, DTG plus TAF/FTC has been our go-to regimen in these difficult to treat patients, who are underrepresented in clinical trials.

- Switching to BIC/FTC/TAF was non-inferior to continued DTG/ABC/3TC [22]. Remarkably few differences after the switch — same renal, bone, lipid outcomes. In clinical practice, this change will lead to a smaller tablet size and avoid ABC-related cardiovascular risk concerns, but otherwise won’t change much. Speaking of …

- A series of studies provided further evidence for the association between abacavir use and cardiovascular risk. On the 10-year anniversary of the first report of this association, a bunch of studies might put an end to this “controversy” — these included mechanistic studies involving platelet reactivity [80, 673], platelets and leukocytes [674], an association with pre-clinical CAD on CT angiography [670], and the predicted clinical impact of stopping abacavir on cardiovascular risk [692]. NA-ACCORD study on this issue also just published.

- Optimal management of 3rd-line ART in resource limited settings includes the use of darunavir/r and raltegravir, sometimes etravirine [30LB]. We can add this study to the numerous others that show that in treatment failure studies, the patients with the least resistance do the worst — it’s a marker for poor adherence. It will be important to document how treatment failures evolve with the widespread implementation of DTG/TDF/FTC, a regimen with a much higher resistance barrier than those with NNRTIs.

- Patients with primary HIV infection in France had remarkably high levels of transmitted integrase resistance [529]. 7.4%, 5.6%, and 5.3% in 2014, 2015, 2016, respectively. I wonder what fraction are clinically relevant mutations vs. polymorphisms. On this same topic …

- One patient in the treatment-naive studies of BIC/FTC/TAF had transmitted resistance to dolutegravir [532]. I believe this is the first time such high-level integrase resistance has been found in a treatment-naive patient. Since baseline integrase genotyping was not required for study entry, it was picked up retrospectively. The patient was randomized to BIC/FTC/TAF, and achieved virologic suppression.

- Certain patients with a history of lamivudine resistance can maintain virologic suppression on a two-drug regimen of lamivudine plus a PI or integrase inhibitor [498]. These M184V patients did, however, have more virologic “blipping”, suggesting that HIV control was less robust than with triple therapy. It’s also an observational study, not a randomized trial, and I can’t imagine choosing to use a two-drug 3TC-containing regimen in someone who is known already to have resistance.

- Women switching to BIC/FTC/TAF tolerated the regimen well and maintained virologic suppression [500]. Most had been receiving EVG-containing regimens previously. Since the licensing studies of this regimen had so few female participants, this trial of over 400 women is important if only to show that the treatment is effective in women too.

- San Francisco has been making remarkable progress in starting ART as soon as possible in newly diagnosed patients [93]. From 2013 to 2016, the median time from first care to initiating therapy decreased from 27 days to 1. Not surprisingly, the time to viral load < 200 also dramatically dropped, from 134 days to 61 days. A decrease in time to start ART was seen in all demographic groups, including traditionally vulnerable populations (racial and ethnic minorities, homeless).

- In a randomized strategy study, same day ART initiation again proved better than standard of care in patient engagement, virologic suppression [94]. Study was conducted in Lesotho, and the novel aspect is that it was also done after home HIV testing. Paper also published in JAMA.

- Sertraline does not improve outcomes in cryptococcal meningitis [36]. This commonly used antidepressant has in vitro antifungal activity, but didn’t do anything here, prompting early discontinuation of the study for futility. It was certainly worth trying — we definitely need strategies to improve the outcomes with this challenging disease!

- Discontinuation of DTG due to CNS side effects is not associated with prior psychiatric diagnoses or plasma levels [424]. The discontinuation rate for DTG overall was 6%, and female sex and older age were risk factors. The lack of association with plasma levels differs from a previous study done in Japan.

- Patients surveyed about their preference for novel dosing strategies for ART chose “a single pill taken once a week” as preferred [503]. The other options were “two shots given in the clinic every other month” and “two small plastic implants in the forearm every 6 months.”

- Treatment of HIV controllers with TDF/FTC/RPV reduces T-cell activation and markers of immune exhaustion [229]. (Disclosure: co-investigator.) Plasma HIV RNA also further declined, and treatment was associated with a modest improvement in quality of life. No effect on absolute CD4 cell counts or HIV DNA.

- Only 11% of MSM with acute HCV clear the virus spontaneously [129]. If there is < 2 log drop in HCV RNA by week 4, then clearance is extremely unlikely. The data suggest treatment should be offered at that earlier time point (week 4), for the benefit of both the patient and to prevent further ongoing transmission.

- In coinfected patients, FTC/TAF (as part of the BIC/FTC/TAF regimen) shows good activity vs hepatitis B [618]. In this secondary analysis of prospective clinical trials, one patient randomized to a non-TAF regimen acquired hepatitis B.

- New HIV infections in Australia have dropped dramatically in association with widespread use of PrEP [88]. The bulk of their HIV epidemic is in MSM, making the target for HIV prevention clear. Plus, one Australian clinician told me that around 95% of those in care are virologically suppressed, which beats the typical US-clinic suppression rate of 85% or so.

- Very low doses of MK-8591 protect rhesus macaques against SHIV infection [89LB]. Results suggest this drug might be suitable for less frequent dosing as a PrEP strategy.

- Crystal methamphetamine is bad for your telomeres [760]. In a cross sectional study comparing HIV infected people who do and do not use crystal meth, along with HIV negative controls, those who were HIV infected with meth use had telomere “T/S ratios” consistent with 20 years of accelerated aging. This rings true from clinical practice! What a terrible drug.

The dates of CROI are no longer a tightly kept secret (hooray!), so we already know that next year’s meeting will be in Seattle, March 4-7, 2019.

As for here in Boston, we’re getting ready for our next big storm.

So what did I miss?

March 4th, 2018

Winner of ID Cartoon Caption Contest #3, and Here’s #4 Just in Time for CROI

One of the challenging aspects of writing this blog is that there is so much interesting material in the ID/HIV world that sometimes I forget to cover critical items.

Example: the winner of the most recent ID Cartoon Caption Contest, which I’m embarrassed to admit, has been awaiting its announcement since late 2016.

The winner:

It’s a great caption, trouncing the very strong competition of 3 other finalists by garnering 62% of the vote.

But I confess we here at NEJM Journal Watch were torn between this one and “Have you tried switching him off and back on again?,” which we thought would finish stronger than its 13% of the total vote.

Concerned, we asked our crack team of cybersecurity experts to investigate further, and we’re proud to announce there was no Russian meddling in the voting process. Hence, the winner is clear.

So congratulations to Steve V., who submitted the top caption! As I’m sure he’s aware, he’s the winner of a lifetime free subscription to this blog, good in all 50 states and US Territories. If Steve V. is from another country, he can continue to access the blog provided he has a valid yellow fever vaccination certificate.

Now, onto the next contest. Some of us in the ID/HIV world will be coming to Boston for CROI this week, but fortunately my skilled collaborator Anne Sax not only isn’t attending CROI, she also has no idea what “CROI” even is.

Working together (my idea, 100% her drawing), we’ve come up with the doctor-patient encounter displayed below, perhaps inspired by last week’s Nor’easter.

As before, write your proposed caption in the comments section, or pop it on my Twitter feed — or, if you’re feeling shy, email it to me at id.caption@yahoo.com.

February 25th, 2018

Is Self-Administered Postexposure Prophylaxis Another Viable Option for HIV Prevention?

Most of the pivotal trials of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) have used daily therapy.

The lone exception is the IPERGAY study. Men at high risk for acquiring HIV took two tablets of tenofovir DF/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC, Truvada) before sex, and one tablet the next 2 days.

The strategy was highly effective in preventing HIV acquisition, and intermittent PrEP is endorsed as an option in France, where the study was conducted.

(About that name — it stands for Intervention Préventive de l’Exposition aux Risques avec et pour les Gays. I have it on good word from the lead investigator that they can say it in French without smiling.)

The main concern some have raised about the IPERGAY results is that participants had relatively frequent exposures (a median of 4/month), enough so that sufficient tissue levels of TDF/FTC could be maintained.

But what about even less frequent high risk exposures, say a few of times a year? Daily PrEP for these patients seems like overkill, and intermittent PrEP may not work. Might they benefit from a different prevention strategy?

A group in Toronto just published a novel approach to these patients — instead of giving them PrEP, they are recommending on-demand postexposure prophylaxis (PEP).

(In the paper, they call it “PEP-in-pocket,” or “PIP,” but I don’t think we can tolerate another one of these single syllable abbreviations in HIV prevention that begins with “P.”)

From 2013–2017, two clinical sites identified relatively low-risk individuals from those who were initially referred for PrEP.

The preventive strategy consisted of prescribing a 28-day supply of TDF/FTC plus dolutegravir, with instructions to start it as soon as possible if the patient had what they deemed to be an exposure that might transmit HIV.

Thirty such people were identified. In the follow-up period, 4 of the 30 initiated PEP on their own, all doing so within 10 hours of the exposure. Each reported good adherence to their treatment, and were closely followed-up.

All who started preventive medications were seen in clinic within a week for clinical evaluation and blood work. There were no HIV seroconversions in 21.8 person-years of follow-up.

Of course, the small size of the study, and its retrospective, non-comparative design hardly are sufficient to incorporate this strategy into guidelines.

Nonetheless, there are several advantages to this on-demand PEP strategy. These include avoiding daily exposure to medications, lower drug costs, reducing emergency room visits, and still providing some preventive intervention, just in case. Individuals who start on-demand PEP multiple times can be transitioned to PrEP, which is what happened to 4 of the patients in this study.

I look forward to hearing more about this approach — and I’d be saying that even if the senior author weren’t a graduate of our ID fellowship program!

(Nice work, Isaac.)

February 19th, 2018

Can We Solve the Morass of Outpatient Intravenous Antibiotic Therapy?

If you want to get an ID doctor riled up, here are a few reliable strategies:

- Get an ID consult on a complex patient just to summarize the chart for your discharge summary.

- Endorse the view that procedural doctors deserve their vastly higher salaries than MDs in cognitive specialties.

- Prescribe azithromycin for patients with bad colds.

- Discharge a patient from the hospital on intravenous antibiotics when an oral antibiotic would work just as well.

I’ve not hidden my distaste for unnecessary “outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy,” or OPAT on this blog, once devoting a whole post to oral antibiotics with excellent absorption.

It’s not just the inconvenience and potential dangers (blood clots, secondary infections from the IV catheters) of OPAT that I dislike. It’s also that there is essentially no support (read: money) for the clinicians charged with monitoring these complex patients, or for coordinating the many people who may be involved in their care.

Payers certainly don’t pay doctors or nurses for the substantial phone time, emails, and faxes that each OPAT patient generates. This may motivate some doctors to schedule unnecessary outpatient visits for these cases — otherwise they’d get nothing.

And since nobody is paying anyone to oversee the care of OPAT patients, there’s often a “Who me?” approach to their follow-up that is neither good for patient care or the morale of their providers.

Or just as bad, there are too many cooks in the kitchen, and no one is quite clear who’s responsible for what.

A recent post on the IDSA website by ID doctor Parker Hudson detailed this thorny issue perfectly:

Our OPAT program spends a disproportionate amount of time trying to track down labs/levels from patients on IV antibiotics who were discharged to SNFs [skilled nursing facilities]. Despite our orders and requests, most of these values are interpreted and managed by medical directors and not sent back to us — the ID docs writing the orders and following up the patients.

What followed were literally dozens of comments from other ID doctors with similar problems, problems we certainly experience on a daily basis with our OPAT program as well.

To illustrate the complexity, here’s a case — and then a very simple poll.

A 57-year-old man with diabetes and chronic renal disease is referred for admission by his primary care provider (PCP) with 2 weeks of progressive back pain, and found to have spinal osteomyelitis secondary to MRSA. A peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line is placed, and because of severe ongoing pain, he is discharged on hospital day 5 to a skilled nursing facility to complete 6 weeks of parenteral vancomycin and to receive physical therapy. At the time of discharge, his ID consultant (who does not do outpatient ID care) recommends that safety labs be done twice weekly, and vancomycin levels once weekly. An outpatient appointment with a different ID doctor is scheduled for 4 weeks later, as well as with his PCP.

Now, take the poll — and if you have a moment, provide the rationale for your answer in the comments section. Bonus points for any practical solutions to the OPAT morass — they would be most welcome!