An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

September 7th, 2020

Relieving the COVID-19 Testing Logjam by Separating the Symptomatic from Asymptomatic

As the days grow shorter and we celebrate Labor Day here in the United States, the end of summer looms awfully near. With that will soon come colder temperatures, more time spent indoors, kids back in school, and the inevitable respiratory virus season.

As the days grow shorter and we celebrate Labor Day here in the United States, the end of summer looms awfully near. With that will soon come colder temperatures, more time spent indoors, kids back in school, and the inevitable respiratory virus season.

How we address these “viral URIs” in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic presents a major challenge for clinicians, patients, healthcare systems, and — the focus of this piece — diagnostic laboratories.

Because while certain symptoms might suggest rhinovirus or influenza or RSV or adenovirus or metapneumovirus more than SARS-CoV-2, there is no single clinical sign or symptom that would reliably separate one from the other.

Which means that essentially everyone with a viral respiratory tract infection is eligible for — and arguably needs — COVID-19 testing. This adds considerable volume to an already overburdened testing system that, in this well-argued piece by Atul Gawande in The New Yorker, is “as messed up as a pile of coat hangers.”

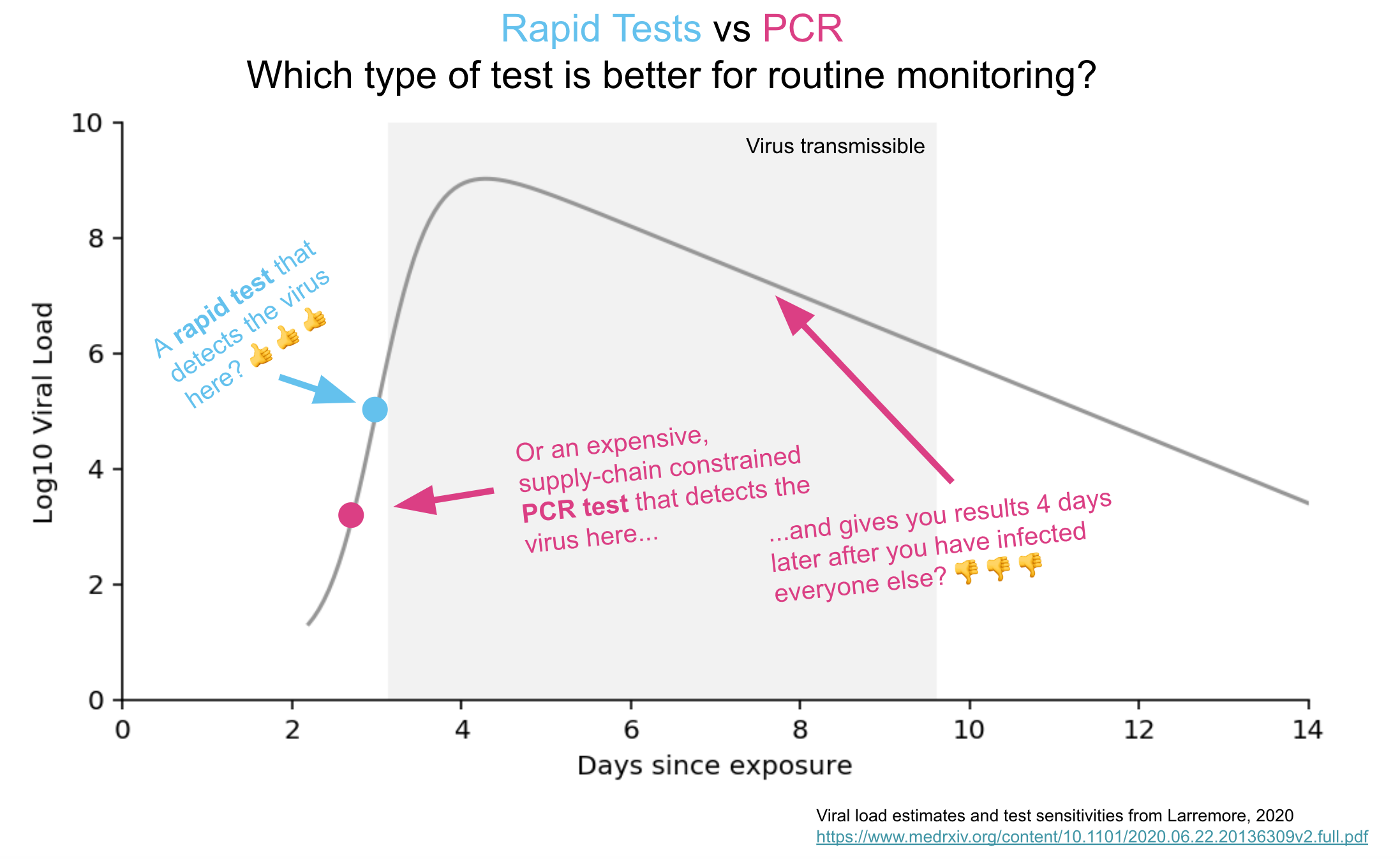

What I would propose is that we start by separating out symptomatic from asymptomatic testing. Let’s use a quick and less expensive antigen test for asymptomatic testing, and save the PCRs only for people with symptoms.

We have to do something. The demand for asymptomatic COVID-19 testing is already off the charts, increasing all the time.

One of my colleagues mentioned to me that testing people without symptoms is at least 40% of our hospital’s testing volume. Most of these tests are for admissions (all get tested) and for pre-procedure tests, but increasingly also for travelers re-entering Massachusetts or visiting Maine, people who want to see elderly family or friends, as part of school entry requirements, or just someone worried about a recent potential exposure.

But, you note, aren’t these antigen tests notoriously inaccurate? Won’t they miss cases because they aren’t as sensitive as PCR? Indeed, something of a backlash on rapid home testing appeared recently in a New York Times piece (one I happen to disagree with, for the record), and this lack of sensitivity was highlighted:

Experts also noted that antigen tests aren’t great at sussing out small amounts of the coronavirus, which means they’re far more likely to miss a case that a technique like PCR would catch.

For testing of asymptomatic individuals, it’s worth addressing this concern head-on. Because over the last week, I’ve been asked several times to explain why tests for COVID-19 could be different in symptomatic versus asymptomatic people.

Once it was to a group of research scientists.

Once it was to a local news reporter.

Once it was to a gastroenterologist.

Once it was to a bunch of friends in our backyard, during a socially distanced gathering.

All were worried about lower sensitivity of non-PCR testing.

From this diverse group of people, we can conclude that the concept of accepting a less-sensitive test for testing people without symptoms deserves further clarification — it’s a tough one to master, employing the scary-sounding concepts of Bayes’ Theorem.

So let’s get out our #2 pencils, or our handy Bowmar Brain, and do the math. And, following up on a presentation I made this past week on the topic, and a piece co-authored last month with my colleague Dr. Jeffrey Schnipper, we’re going to consider a very simple case.

(The nice editors at STAT wouldn’t let us publish the full math, except in a linked appendix. Since this is my blog, I can write what I want, so am including it here.)

Here’s the case:

August 2020, Boston.

41-year-old woman planning her summer vacation.

Business consultant; has been working remotely since mid-March.

Lives with husband and 2 children, ages 13 and 9.

Completely asymptomatic; everyone in the household well.

Needs testing for COVID-19 before entering the state of Maine.

What are the chances this woman has a contagious infection with SARS-CoV-2? (She has no symptoms, so that’s the “disease” we are testing for.) We’ll call this estimate our pre-test probability — it’s the likelihood a disease is present even before we do any testing.

In asymptomatic people in Boston currently, the pre-test probability is at most 1%. This is the positive test rate at our hospital now among people without symptoms. Now that we have that estimate, it’s math time!

- For 1000 people like this currently, 10 (1% of 1000) will have COVID-19, and 990 would have nothing.

- A test with 80% sensitivity will be positive in 80% of these 10 — or 8, missing 2 cases.

- The test will be negative in 992 people, which includes the 990 without COVID-19, plus the 2 with the infection we missed.

- The negative predictive value — which is how often the test correctly calls someone negative — is 990/992, or 99.8%.

The chance of missing an infectious case with antigen testing is only 2/1000 — and potentially lower since those who are most infectious have the highest amounts of virus, making false-negative results less likely. This 99.8% negative predictive value is plenty high enough for routine use in asymptomatic people, where the goal is detecting people who might be contagious without knowing it.

In fact, the big worry for testing asymptomatic people is the opposite — a false-positive result. Since false positives are so much more likely in a low prevalence population, all positive results will need confirmation by PCR.

But the take-home message from going through this exercise is that we should not hesitate to deploy “good enough” testing for screening low-risk people without symptoms. The pre-test probability is key to defining the trustworthiness of a test result.

And now you can cue the Jim Gaffigan-esque self-criticizing, high-voice stage whisper: Did he just to write about COVID-19 testing again? Can’t he write about anything else?

Hey, last week I wrote about reinfection!

Take it away, Jim — we need you now more than ever!

August 30th, 2020

Cases of SARS-CoV-2 Reinfection Highlight the Limitations — and the Mysteries — of Our Immune System

In case you didn’t notice, or perhaps were “off the grid” taking some well-earned time away from COVID-19 news, this past week we heard about several cases of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection.

We’ll come back to them in a moment, but first, some questions:

- Why does one parent never get sick when their kids start coughing and sneezing and dripping with colds, while the other gets a cold every single time?

- Why do some tourists happily dine on delicious street food in Mexico City, while this same cuisine will put others in their hotel bathrooms for the whole trip?

- Why are some people repeatedly plagued with strep throat, while others never get it in their lifetimes?

- Why is infection with Epstein Barr virus (nearly 100% in humans by adulthood) most of the time asymptomatic, while a certain unlucky few will be laid up with severe mononucleosis for weeks?

- Why did some gay men in U.S. cities contract HIV in the early 1980s after relatively few exposures, while some others with multiple known HIV-positive contacts never did? How did some commercial sex workers in Africa in the early 1980s escape HIV?

- Or, perhaps most relevant to the COVID-19 re-infection cases, why do some people get the flu twice within the same flu season? Or some (rare) people get chicken pox twice? (The second case is usually quite mild, fortunately.) Or even measles!

I start with these examples (and I could have chosen dozens more) to highlight that there’s a ton we don’t know about infection, immunity, and how they interact to protect us — or not to protect us — from disease.

So after hearing anecdotes about SARS-CoV-2 reinfection for months (many of them false-calls based on persistent low-level PCR positivity, not reinfection), now we have actual cases, and it’s worth considering some of the details.

The first occurred in a 33-year-old man 142 days after his initial symptomatic infection. Authorities picked up the infection on a screening test when he went through the Hong Kong airport, as he had no symptoms. In fact, he remained asymptomatic throughout. A brisk antibody response developed shortly after, a response not detected the first time.

Sequencing the virus from the two infections showed sufficient differences to prove reinfection, rather than relapse.

As noted wisely by immunology professor Dr. Akiko Iwasaki, “This is no cause for alarm – this is a textbook example of how immunity should work.”

Phew.

News then broke with additional cases in Europe and Ecuador, about which we have limited details.

But this U.S. case in a 25-year-old immunocompetent man from Nevada deserves attention, and likely some worry.

Here are the clinical details of the history, summarized from the available pre-print (it has not yet been peer reviewed):

March 25: Onset of sore throat, cough, headache, nausea, diarrhea.

April 18: Tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR.

April 27: Symptoms resolved.

May 9 and 26: Tested negative for virus by two methods.

May 28: Onset of fevers, headache, dizziness, cough, nausea, and diarrhea. Chest x-ray negative.

June 5: Symptoms worsened, and now with hypoxia; admitted to the hospital and found to have new infiltrates on chest x-ray. PCR positive for SARS-CoV-2.

June 6: SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibody positive.

The authors state that the viruses isolated from the first and the second illness show sufficient genetic differences to support reinfection, rather than relapse. The likely source of the second infection was a parent, suggesting household transmission, though the sequences from the parent are not available.

These important case reports raise many questions, about which today we can only speculate, which is why many of the sentences following have question marks.

- How often does reinfection happen, and why? It doesn’t appear common, but we must conclude from these cases that it does occur. Perhaps with similar frequency to other coronavirus infections in humans?

- Will cases be as severe as the first infection? Based solely on the Nevada case’s household contact, it’s possible that severity may be related to intensity of exposure. Maybe he was not taking precautions in the household, believing himself immune? Some believe inoculum is an overlooked aspect of COVID-19 disease severity.

- When reinfection happens, will these new cases carry the same risk of transmission as the first infection? We will have to assume so, but it is plausible that an immune response will render people less infectious to others.

- How do these cases factor into policies about screening people who have already recovered from COVID-19? Given the long duration of PCR positivity in some people, some infection control specialists have advocated not retesting people who are admitted with prior disease if they are asymptomatic. Same for preprocedural screening. Seems we may need to put this policy change on hold until we have further data on reinfection, and how often it occurs.

- What are the implications for vaccine efficacy? Will a vaccine even work? If so, for how long? The cases suggest that a vaccine may need to be repeated periodically, but optimists can point to the HPV vaccine as a model of how vaccine immunity can be stronger than natural immunity, so we’ll see.

So remember, there’s a lot we don’t know about our immune system, and how it works — and this is particularly true for a new infection and disease.

But one thing I do know?

“Immunity Passports” are dead.

August 24th, 2020

FDA’s Emergency Use Authorization for Convalescent Plasma for COVID-19 Seems To Be Fooling No One

Starting late Saturday night, and proceeding the next day — like a relentless series of coming attractions for a blockbuster summer movie or the finale of a reality TV series — we repeatedly heard word that the President planned to make an announcement Sunday evening about a “major therapeutic breakthrough” in treatment of COVID-19.

Starting late Saturday night, and proceeding the next day — like a relentless series of coming attractions for a blockbuster summer movie or the finale of a reality TV series — we repeatedly heard word that the President planned to make an announcement Sunday evening about a “major therapeutic breakthrough” in treatment of COVID-19.

6 p.m. Eastern. Live. Get ready. Here it comes.

And, satisfying the ratings-hungry entertainer he once was (and some would say still is, though “entertainer” must be used cautiously in this context), we turned up to hear him cite this “powerful therapy” that “had an incredible rate of success.”

No, it’s not hydroxychloroquine.

This time it’s convalescent plasma. That liquid gold harvested from recovered COVID-19 patients, swimming in antibodies directed against SARS-CoV-2, and also containing a veritable secret sauce of illness-reversing substances that have fascinated doctors and scientists for decades.

Never mind that harvested convalescent plasma isn’t used commonly to treat any infection currently.

Or that the randomized trials of this treatment have so far been disappointing.

Or that the observational data the FDA used to justify their action come from an unpublished study not yet subject to peer review.

(Here’s the next best thing, for those inclined to take a deep dive into data analysis.)

Or that the very experts employed by the government to review plasma’s safety and efficacy have as recently as last week raised important concerns about the lack of convincing evidence for this treatment.

Or that this action by the FDA will almost certainly jeopardize any existing randomized trials of convalescent plasma in the United States.

Or that the person from the FDA who reviewed the plasma data had his name redacted from the memo.

Or that the emergency use authorization may make patient care more difficult, since this will necessarily be a limited resource — especially if antibody titer turns out to be a critical determinant of whether this works, and since antibodies appear to fade in many people soon after they have COVID-19.

Nope — no matter. On the evening of a major political event — timing that cannot be coincidental — the president got his ratings.

He had to do a little intimidation, but we’re getting used to that.

The deep state, or whoever, over at the FDA is making it very difficult for drug companies to get people in order to test the vaccines and therapeutics. Obviously, they are hoping to delay the answer until after November 3rd. Must focus on speed, and saving lives! @SteveFDA

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 22, 2020

The good thing is that no one in the scientific community is fooled. I have not heard from a single ID specialist who believes this action was supported by existing data, and indeed our professional society agrees.

Convalescent plasma may work to help people with COVID-19.

But if it does, we don’t know how much, or who are the most likely to benefit, or how to select the right donors.

Because given the absence of controlled trials, right now in the U.S. what we have are 70,000 anecdotes — that’s how many people have received it in this country — tied together by individual reports and separate observational studies.

For the true evidence, we’ll have to wait for the randomized, controlled clinical trials.

The ones going on in other countries.

August 16th, 2020

Picking the Top Internet ID Resources, and a Wistful Look Back at the CDC That Was

Over on Open Forum Infectious Diseases — and that’s abbreviated “O-F-I-D”, not “Oh-fid”, thank you — I sometimes invite other ID-types to join me on a podcast to pick their favorite ID-related item:

Examples of these mock “drafts”:

And some time this past winter (a million years ago), ID PharmD extraordinaire Monica Mahoney came up with a great idea for one of these drafts — top ID-related internet resources.

We recorded it in my office in February, our wonderful audio editor Meredith Mazzotta edited the audio file to make us sound more articulate — and then, because I was on service in late February, we didn’t post it right away.

Well, you know what happened next. A pandemic happened, meaning the world exploded. It didn’t seem quite right to release something so lighthearted and COVID-free in March.

Tell me — would you have wanted to read something about the joys of air travel in mid-September, 2001? So we shelved it, awaiting a more stable time.

Fast-forward to now, and I’ve decided we’re ready. After all, Monica is thoughtful and funny and loves to teach, so why not expose the world to her talent?

But before you listen to our picks, I’ll share my #1 pick of the best ID internet resource at the time, because it has special resonance now in a post-COVID-19 world. It’s the CDC web site, and here’s what I said (lightly edited):

I think the CDC site is a work of genius. It’s comprehensive. It’s broad. It’s updated all the time. It’s graphically terrific. It shows you sometimes your taxpayer dollars do really good work. I use it for all kinds of things. Example: I am not a travel medicine doctor, but of course, all ID doctors get asked travel questions. I use it for that all the time. Not surprisingly, when there are emerging outbreaks, it is the first place you go to find the latest information. They are extremely diligent about keeping it up to date. … It is really a remarkable thing, and it makes me very proud and very patriotic (sometimes not easy these days), to say that cdc.gov is my number one choice for an ID internet resource.

I bolded that last part, since it’s so painful to read today.

Not because what I said was wrong at the time. If we think back to Zika, Ebola, pandemic flu, West Nile, Candida auris, HIV, HCV, STIs — basically anything except COVID-19 — the CDC site has been the place to go to find the most updated and reliable information.

Now, not so much. Never has so much talent and potential been wasted, undermined by a federal government that seems intent on undercutting what CDC does best, which is responding thoughtfully and carefully to infectious threats, using the best available data.

Wouldn’t it be great if these experienced public health officials were given the resources and allowed to use their expertise to take control of our national COVID-19 response? If they issued frequent briefings with the latest national information? If they remained free of the politicization that has so bedeviled our response to the pandemic right from the start? From a recent outstanding summary, published in The Atlantic:

On February 25, the agency’s respiratory-disease chief, Nancy Messonnier, shocked people by raising the possibility of school closures and saying that “disruption to everyday life might be severe.” Trump was reportedly enraged. In response, he seems to have benched the entire agency. The CDC led the way in every recent domestic disease outbreak and has been the inspiration and template for public-health agencies around the world. But during the three months when some 2 million Americans contracted COVID‑19 and the death toll topped 100,000, the agency didn’t hold a single press conference. Its detailed guidelines on reopening the country were shelved for a month while the White House released its own uselessly vague plan.

Isn’t it the height of irony that no one uses the CDC as a source for the latest numbers on new cases, percentage of positive tests, hospitalizations, and mortality?

Sure, they still do some good COVID-19 related research, and set important policies using the best available information.

But they could be doing so much more, if given the chance. Aaugh! So frustrating.

So take it away, Monica. Let’s hear about some other great internet resources. And use the comments section to let us know yours.

(Read the transcript: Debating the Top ID Internet Resources with Dr. Monica Mahoney.)

August 4th, 2020

Carbapenems and Pseudomonas, Lyme and Syphilis Testing, a Bonus Point for Doxycycline, and Some Other ID Stuff We’ve Been Talking About on Rounds

As noted multiple times, many of us ID doctors attend on the general medical service. This offers us a chance to broaden our patient care activities and to work with medical students, interns, and residents.

As noted multiple times, many of us ID doctors attend on the general medical service. This offers us a chance to broaden our patient care activities and to work with medical students, interns, and residents.

Boy, that’s fun!

Yes, those of us who attend on medicine enjoy it enormously, though the experience humbles us on a daily basis about what we need to learn in cardiology, nephrology, gastroenterology, rheumatology, hematology, endocrinology — you name it.

Fortunately, the smart trainees (and subspecialty consultants) teach us tons.

Plus, at our hospital we have a co-attending system, meaning my knowledge can be amplified by another experienced doctor — this month an endocrinologist, who has fortunately for all of us never encountered a metabolic disturbance (electrolytes, minerals, glucose) he can’t solve.

https://twitter.com/BrighamChiefs/status/1285652513333686274?s=20

So this week we take a partial break from the COVID-19 coverage, and summarize some ID stuff we’ve chatted about on rounds.

- Meropenem and other carbapenems are not good drugs for treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.. Resistance can develop quickly through alteration of porins or increased efflux pump activity. Ertapenem, for the record, has no reliable activity at baseline. And did you know that ID docs often abbreviate this tricky but common organism as PsA?

- Doxycycline partially protects against the development of C. diff. Yet another a reason why it’s many ID docs’ favorite antibiotic. Bonus podcast at the bottom of this post.

- Diagnostic testing for Lyme disease is a mess. Link is to a very quick slide set. And yes, we still await the final publication of the Lyme IDSA guidelines, released in draft form last year, and expected in the late summer/early fall.

- Diagnosis of another disease caused by spirochetes — syphilis — is also a mess. How many people can clearly explain what a one dilution, one tube, or two-fold change in the RPR means? (Hint, they’re all the same thing.) Link is to another quick slide set. Great new graphic below by the folks from The Clinical Problem Solvers, with a couple of minor suggestions, including a pet peeve — the “need” for LP in ocular/otologic disease. Why do it if you’re going to treat for neurosyphilis regardless of the results?

Very nice graphic! Suggestions:

– Please include the T. pallidum enzyme immunoassay (TP-EIA), which has become the preferred screening test in many places

– Need for LP in ocular/otologic disease is debatable, since we treat for neurosyphilis regardless of results https://t.co/kE2FCihvRm— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) August 4, 2020

- Ocular syphilis has diverse clinical presentations, most commonly blurred vision, sometimes with photophobia and eye redness. The ophthalmologists will often diagnose uveitis. RPRs are usually high (median titer 1:128 in the linked series), suggesting relatively recent acquisition, but eye involvement can occur at any stage of syphilis.

- Enterobacter and certain other enteric gram negatives may develop resistance to cephalosporins through “de-repression” of a chromosomally mediated beta-lactamase. The confusing thing about this mechanism is that the organisms initially test as susceptible to ceftriaxone, with resistance emerging with noncurative therapy. Cefepime and carbapenems retain activity.

- Sputum is more sensitive than nasopharyngeal samples for diagnosis of COVID-19 in symptomatic patients. Keep this in mind when ruling out the disease in those hospitalized with negative nasopharyngeal swabs; serology may also be useful if symptoms are of 7 days’ duration or longer. Hey, I said this post was a partial break from COVID-19. Can’t be a full break, not yet — boo hoo.

- “Hypervirulent” klebsiella is an increasingly common cause of liver abscess. Unlike other causes of liver abscess, these cases are usually monomicrobial, frequently have metastatic spread, and may have a positive “string test” in the microbiology lab, demonstrating hypermucoviscosity. Disease is more common in Asia.

- Actinomycosis most commonly occurs in cervicofacial, abdominal, pelvic, and thoracic sites. Organism also may be found in relation to IUDs, usually without symptoms. This slowly growing anaerobe takes advantage of anatomic breaks, trauma, or radiation damage, and can cross tissue planes and lead to draining sinus tracts, or masses potentially mistaken for malignancy. Treatment is long-term penicillin (or amoxicillin).

- None of the recommended first-line HIV treatment regimens include the pharmacokinetic boosters cobicistat or ritonavir. Such boosters greatly increase the risk for drug interactions. This means previously popular treatments — in particular the mellifluously named Genvoya — should be retired as initial therapy.

- Aztreonam has a similar mechanism of action as beta-lactam antibiotics (inhibiting cell wall synthesis), but does not cause similar IgE-mediated type-1 hypersensitivity reactions. One possible exception is for patients allergic to ceftazidime, which has a similar side chain (and antibacterial spectrum). Active only against aerobic gram negative infections, aztreonam has few other indications aside from this lack-of-allergy niche. OK, maybe no other indications!

- Chlamydia psittaci is a rare cause of community-acquired pneumonia. And it’s a favorite of ID case conferences and CPCs. Since the primary source is household birds — especially parrots — I was luckily given the following clues in the linked CPC to frame the discussion, which reads like a ID board exam question:

The patient lived in New England and installed air-conditioning equipment. He owned a ferret and five snakes, to which he fed frozen rabbits and live or frozen rats that he obtained from a pet supply store. His brother owned a healthy puppy. The patient had returned 27 days earlier from a 10-day trip to Hawaii, where he had cut himself on coral while scuba diving. Several of the hotels that he visited had caged parrots in their lobbies.

- The ratio of trimethoprim to sulfamethoxazole in the combination tablets is 1:5. A single strength has 80 mg/400 mg, and a double-strength twice that — hardly anyone knows these arcane facts (except for pediatricians and pharmacists). And aren’t my math skills impressive? Here’s a tip: Since no one on rounds wants to say “trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole” (too long), go with “trim-sulfa.” It’s a better abbreviation than the brand names “Bactrim” or “Septra” (both of which should be retired), and it makes more sense than “co-trimoxazole.” Oh, and this is one of several antibiotics with excellent oral absorption.

- Anaerobic bacteria can cause urinary tract infections. Consider these organisms when your standard urine culture is negative, especially in patients with anatomic abnormalities. And trim-sulfa (commonly used for UTIs) won’t be active against these organisms. Check with your microbiology laboratory about how to evaluate further.

All this antibiotic talk! On the first day of rounds this week, during introductions, one of the residents asked us to say our name and our favorite antibiotic.

Good time to replay the antibiotic draft I did with my friend Dr. Rebeca Plank!

July 26th, 2020

Time to Amplify Our Voices Calling for Inexpensive Rapid Home Testing for COVID-19

Earlier this month, I highlighted how inexpensive rapid home testing for COVID-19 could get us out of this mess faster than a vaccine.

To spare you re-reading the whole thing, here are the main points.

Imagine a simple test done on a saliva sample placed on a paper strip. Results back in 15 minutes. Available without a doctor’s order. A couple of dollars per test. Would be as easy to perform as a home pregnancy test.

And, most importantly, the results will highly correlate with what we care about the most when testing a person without symptoms — are they infectious to others?

With testing applied broadly, and a negative test in hand, think of the implications!

Outpatient visits and procedures. Hospital visitors. Schools and universities. Air travel. Public transportation. Fitness clubs and gyms. Educational, business, and research conferences. Hair salons and barbershops. Bars and restaurants. Houses of worship. Nursing homes. Meat-packing plants, agricultural jobs, transit, and other high-risk work. Choral practices. Cruises. Homeless shelters. Dormitories and military barracks. Spectator sports. Prisons and jails.

Endless, really.

Prototypes for these tests, or slightly more complex versions, already exist. So what’s the hold-up?

Even though numerous companies and academic groups are working on such tests, there’s no guarantee the FDA will approve them — especially since they’re going to be less sensitive than the gold standard PCR tests we use for symptomatic people.

But this lack of sensitivity shouldn’t block availability, since the tests likely will be positive during the few days that people have the highest titers of virus in their respiratory tract, and hence are most contagious. The quantity of virus in this early period (as measured by cycle thresholds) often is millions-fold (or more) higher than just a week later. Rapid tests done regularly should be able to capture this period of exponential viral growth.

And a reasonably accurate test with results back quickly is far better than no test at all — or, as is sometimes happening, a test done with frustrating and potentially dangerous delays in results due to testing backlogs.

Hey @michaelmina_lab, this one's for you! h/t @boulware_dr @StarTribune SteveSack. pic.twitter.com/waA3PpKtAO

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) July 25, 2020

At this point I should note the major inspiration on this topic all along has been my brilliant colleague, Dr. Michael Mina, who has become a persuasive and passionate champion of the rapid home testing strategy. Here he and economics professor Laurence J. Kotlikoff advocate approving these tests and then making them available to everyone:

Once paper strips’ efficacy is definitively proved and they are cleared by the F.D.A., Congress can quickly authorize the production and distribution, for free, of a year’s supply to all Americans. Then we’ll have not only a true day-to-day sense of Covid-19’s path. We’ll also have a far better means to quickly contain and end this terrible plague.

Michael has been making the rounds pushing the idea, and fortunately, it’s starting to get a broader audience. I mention it often enough that my immediate family must wonder whether I’ve replaced my baseball obsession with a new one. (They may be right.)

And while I read with interest about how the NIH plans to rapidly scale up testing, the home testing component of the program gets scant mention.

Full disclosure, I have my own personal reasons for wanting easily available rapid tests — reasons that go beyond wanting to go out to a nice dinner, to start up my neighborhood poker game, or to visit Fenway for some baseball. Yes, those would all be nice.

But mainly, it’s this — my parents live in New York City and have essentially been in full shutdown mode for months. The cultural activities of the city that so enriched their lives — movies, plays, operas, lectures, book clubs — have vanished. Even worse, they’ve had minimal non-Zoom contact with family or friends, including their children, grandchildren, or great-grandchildren.

Their life now isn’t great. But they grew up during the depression, lived through World War II, and as a result have maintained a cheerful perspective all along that takes into consideration how things could be so much worse. One of their friends, for example, had COVID-19 and is still recovering, months later. And they know that hundreds of thousands have died.

But now, my father needs major surgery. The hospital strictly limits visitors — one a day. And so the barrier to human contact — on our being able to visit and to comfort him safely — becomes more than just an inconvenience. It’s frankly heartbreaking.

So send good thoughts his way. He’s quite something, as I’ve mentioned.

Finally, take 17 minutes and watch this excellent video on the science and rationale behind rapid home testing — it draws heavily on a longer interview Michael did on This Week in Virology.

And if you have friends in powerful places, let’s push to make this potential breakthrough a reality — if not as national policy, can we do it at the state or city level? Because it can’t come soon enough.

July 19th, 2020

Reaching Out to ID Doctors in COVID-19 Hot Spots — You Must Be Truly Exhausted

For us ID doctors in most of the northeastern United States (and Chicago and Detroit and some other northern cities), March and April hit us like a giant wave of never-ending calls, pages, emails, and crises.

For us ID doctors in most of the northeastern United States (and Chicago and Detroit and some other northern cities), March and April hit us like a giant wave of never-ending calls, pages, emails, and crises.

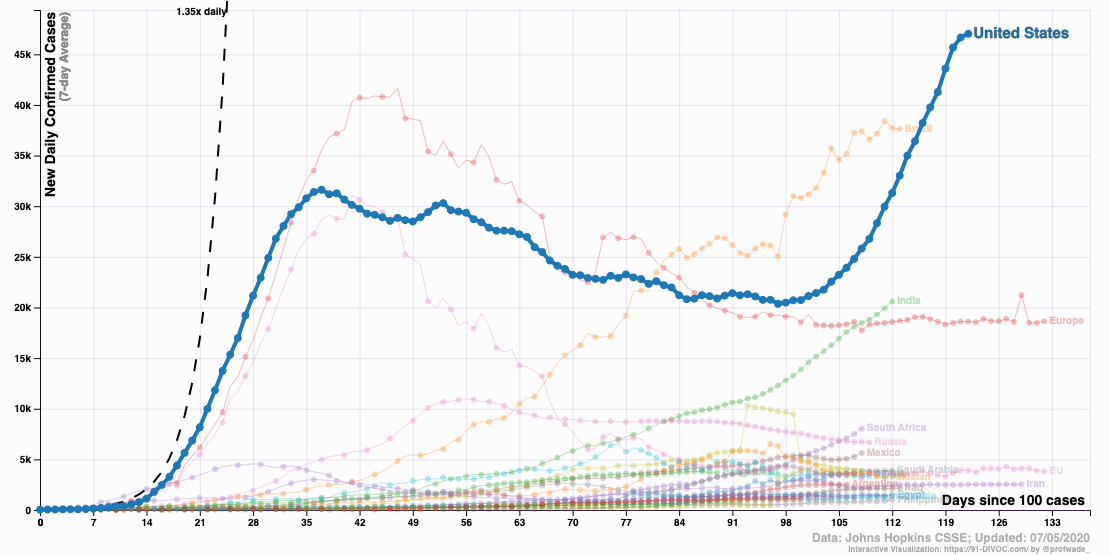

With COVID-19 case numbers increasing every day, the challenges crashed down on us in an endless torrent of hospital needs and responsibilities.

The emotional toll of seeing so many critically ill patients for whom we didn’t have any proven therapies was only part of it. We were also the group to whom everyone turned for help — everyone had questions.

We know you must be swamped right now, but … started many a query.

No surprise. This is an Infectious Disease, after all. “It’s what you signed up for,” as one of my friends, a lawyer, put it succinctly with a shrug.

But it’s also something none of us had ever seen in any of our lifetimes. No one is old enough to remember the 1918 influenza pandemic. No one really knows what to do, or how to do it.

Which is why the work of handling COVID-19 can be endless.

Want an example? Someone tallied what one of my extraordinary colleagues — she ran our “biothreats” response team — gave to the COVID-19 effort, which started for her in early March:

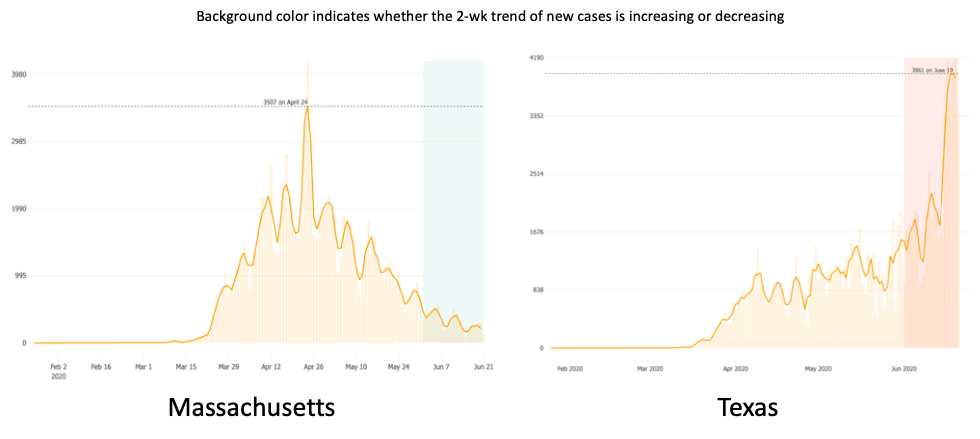

Needless to say, it came as an enormous relief when case numbers started to drop. For Boston, this started in early May.

Here’s what Dr. Stephen Smith, writing in late June, said about his experience in northern New Jersey (reprinted with permission):

In my private ID practice in northern NJ, 18 miles west of New York City, we have treated over 200 hospitalized COVID-19 patients, many in the ICU. We peaked in early April. Then in early May, it was as if someone turned off the spigot. Since then, we have been consulted on only 20 patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, but only a minority was admitted with COVID-19 symptoms. We have not intubated a patient with COVID since early May.

We are hesitant to use the “A” word (attenuation). Like the reverse of saying Lord Voldemort’s name, we are worried that if we say the “A” word, it won’t happen.

To what do we owe this lessening of the COVID-19 burden, especially now that cases are increasing in most of the rest of the country?

While herd immunity might play some role — I remain hopeful, despite discouraging reports on low seropositivity in hot spots — much more likely is that we’ve been adherent on a societal level with implementation of various low-tech strategies.

Social distancing. Banning communal indoor activities. Closing bars and restaurants. Asking religious institutions to worship over Zoom, or outside. Wearing masks in public, especially indoors.

These things, you know, actually work.

While we ID doctors in the northeast bask in this much-needed reprieve, our ID colleagues in much of the rest of the country — initially relatively spared — now have to deal with rising case numbers.

And they must be truly exhausted. Really.

Because it’s not as if they weren’t gearing up for this in the winter. When CROI (the most important national HIV meeting) converted to a “virtual” meeting in early March, many ID doctors from the south and west had already cancelled their plans to come to Boston — COVID-19 already loomed very large nationally to all us ID specialists, and preparation for it was underway everywhere.

Plus, note I wrote that they were relatively spared — they’ve also been seeing some cases right from the start, if not as many we initially did.

So to all ID docs out there in Arizona, Florida, Texas, California, Alabama, South Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, Louisiana, and all the other states experiencing a COVID-19 surge, I’m thinking of you.

And so hoping that your community will get it together, and turn off that spigot soon.

Because when it happens, it brings a relief the likes of which you won’t believe.

July 15th, 2020

Really Rapid Review — AIDS 2020 Virtual

The International AIDS Conference — or AIDS 2020 — shifted from its Bay Area dual locations of San Francisco and Oakland to be entirely online.

Digital. In the cloud. Virtual.

The primary motivation for the switch was to show off what the numerous tech giants in the region could do with this fancy thing called the World Wide Web.

You know — Google, Apple, Facebook, Oracle, Intel, Hewlett-Packard, Cisco, Twitter, Zoom, and the whole gang — flexing their digital muscles.

Ha, ha.

With that silly preface out of the way, here’s a Really Rapid Review™ of some highlights — which encouragingly included some very important HIV research. Off we go with some highlights:

- Long-acting injectable cabotegravir is superior to TDF/FTC for pre-exposure prophylaxis in MSM and transgender women. Sure, we’ve known some of these results of HPTN 083 for ages — that’s May 2020, isn’t time strange these days? But seeing the data makes the results even more impressive, especially since 1) the study enrolled the demographics at highest risk for HIV; 2) both strategies were highly effective, CAB just more so; and 3) based on when incident HIV occurred, it looks like only 5 out of 2200 acquired HIV while actually receiving injectable cabotegravir. That’s an incredibly small number, regardless of what subsequent resistance studies show. Those are strangely not yet available — blame COVID-19.

- People in Boston stopped PrEP due to COVID-19. Completely understandable — why take PrEP if you’re social distancing? Similar COVID-19 effect in Australia. Some things definitely cannot happen with a 6-foot space between you and another person. And the virtual version of this activity does not require PrEP — unless those tech giants mentioned above have figured out something very novel. Jokes aside, this trend will bear watching as COVID-19 recedes in some areas.

- The occurrence of neural tube defects in babies born to mothers receiving dolutegravir at conception continues to drop. From an estimate of 1/100 exposures after the first report 2 years ago, to 2/1000 now, this decline suggests that the initial case cluster (n=4) may have occurred by chance. Good news! Note that the difference in neural tube defects between dolutegravir and other ART exposure at conception is no longer statistically significant.

- Despite a faster viral load decline, DTG-based regimens in pregnancy do not appear to prevent maternal-to-child transmission better than treatment with EFV. An unexpected finding is that among the 1074 pregnancies, there were 5 transmissions to the newborn — and all occurred in dolutegravir-treated moms. Though not statistically significant, this numeric imbalance is something worth watching as tenofovir-lamivudine-dolutegravir rolls out globally.

- Treatment-related obesity may increase the risk of adverse pregnancy and infant outcomes, especially with TAF/FTC + DTG. This modeling study used incident obesity from the ADVANCE trial, where 14% of women on this regimen developed obesity at 96 weeks, to predict the occurrence of varous complications. Examples include gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, large for gestational age, and macrosomia (among others). Note that these adverse outcomes were not seen in the IMPAACT 2010 study, which tested this exact regimen in women starting HIV treatment during pregnancy — and conversely found TAF/FTC + DTG to be the safest treatment.

- In South Africa, people with HIV with COVID-19 experienced a twofold increased risk for death compared to those without HIV. As I noted before, this giant study contrasts with most U.S. and European cohorts both in its sheer size — 4016 people with HIV, if I did my math right — and conclusions about the negative impact of HIV on outcome. An important unmeasured contributor is likely to be social determinants of health — especially poverty.

- A cohort study of 100 people with HIV in the Bronx showed no effect of HIV on mortality. This reassuring result is much more typical of the European and U.S. studies of HIV and COVID-19. An interesting observation is that none of the viremic people with HIV required intubation, further suggesting that immune responses to the virus contribute to the most severe outcomes.

- In this VA cohort study, people with HIV were no more likely to test positive for COVID-19 than HIV-negative controls. Disease outcomes similar as well. Results imply that HIV does not predispose to acquiring COVID-19, nor worsens severity of disease.

- Could the HCV drugs sofosbuvir and daclatasvir be effective treatment for COVID-19? Pooled results from three studies in Iran demonstrated a faster recovery time in those receiving these drugs. Results should be considered hypothesis-generating rather than definitive given the small number of patients treated; a 600-person randomized trial is ongoing. If effective, let’s hope the price comes down, as the price of 14 days of this combination in the USA is nearly $19,000.

- One person (out of five) who intensified treatment of with maraviroc, dolutegravir, and nicotinamide (?) is now off therapy with no viral rebound. His baseline regimen was TDF/FTC/EFV, and he’s been off treatment for 66 weeks; HIV antibody titers are also declining. Could this be the next HIV cure? Or just a very small reservoir, potentially primed to rebound, as in the “Boston” patients after stem cell transplants? Only time will tell.

- In a retrospective study of first-line failure with TDF/FTC and an NNRTI, an strategy of recycling tenofovir versus switching to zidovudine favors the tenofovir approach. Note that this is despite a high proportion of K65R resistance mutations among viral isolates after first-line failure. The results were attributed to better adherence on the TDF, which is much better tolerated than ZDV. Agree 100%, and worth studying prospectively since they contradict WHO guidelines.

- In NAMSAL study, DTG remains non-inferior to EFV at 96 weeks. The importance of this clinical trial, conducted in Cameroon, is that it included a very high proportion of participants with high viral loads (66% > 100K) and/or low CD4-cell counts (33% < 200). DTG treated patients experienced less emergent resistance, but EFV did surprisingly well given what is considered a region with high transmitted NNRTI resistance. Both strategies did worse in the high viral load stratum — something I’d expect we’d see more often if our other treatment-naive studies enrolled a comparable population.

- In the NIX-TB study of bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid for drug-resistant TB, HIV status did not worsen outcomes. The most important toxicity of this regimen — so transformative for treatment of such a difficult infection — is linezolid-related neuropathy.

- In a longitudinal clinic-based analysis, a switch from TDF to TAF leads to a 9-month period of weight gain (1–4 kg). Change in weight then resumes at roughly the same slope as before the switch. Whether this is due to the weight suppressive effects of TDF versus a direct effect of TAF — or both — remains an unanswered question. In support of the former hypothesis, weight change in the HPTN 083 study was less in the TDF/FTC than the CAB arm, just as it was versus the placebo arm of iPrEx and TAF/FTC arm of DISCOVER.

- People with HIV starting treatment gain more weight over time than matched HIV negative controls. This large comparative cohort study from Kaiser demonstrates both a “return to health” phenomenon for those starting treatment with low body weight, and an eventual “overshoot” for those with normal or above-normal weight at baseline.

- Metabolic parameters improved when switching from TAF-based regimens to DTG/3TC in the TANGO study. Importantly, a high proportion of the enrolled participants were receiving “boosted” regimens, mostly elvitegravir/cobicistat/FTC/TAF — the bulk of the benefit came from these switches. No significant differences in weight.

- Standard risk calculators appear to underestimate cardiovascular risk in people with HIV. Data derived from two large clinical databases, one from Kaiser and the other from our health system — which has been newly named “Mass General Brigham” (R.I.P., Partners).

- Patients switched to DTG/3TC did not experience more low-level viremia than those remaining on a three-drug TAF-based regimen. Another analysis from TANGO, this time using “target not detected” as the endpoint of interest.

- People with NRTI resistance do not have more more “blips” if suppressed on BIC/FTC/TAF or DTG plus FTC/TAF. Guess if you’re suppressed on these high resistance-barrier integrase inhibitors, you’re really suppressed.

- Participants with virologic failure on doravirine plus islatravir as initial therapy experienced only low-level viremia. In these data from the Phase 2 study, all confirmatory viral load values were <80, so none met criteria for resistance testing. The presentation included a table with the research plans for this DOR/ISL combination, which includes fully powered studies in treatment-naive patients (vs. BIC/FTC/TAF) and switch studies.

- Among NNRTIs, doravirine was most likely to be active against over 4000 viral isolates sent for HIV drug resistance testing. At a biologic cut-off of threefold change, 92.5% of the isolates retained doravirine susceptibility, including 45–62% of those resistant to other NNRTIs. Isolates with single mutations (e.g., K103N or Y181C or V106I) generally remained susceptible.

- The pharmacokinetics of subcutaneous injections of lenacapavir support an every 6-month dosing interval. Introducing a new antiretroviral name for this investigational CAPsid inhibitor (note the third syllable)! A key question is what partner should accompany such an infrequent administration, and at what intervals.

- There is no significant drug interaction between darunavir/ritonavir and dolutegravir. Good thing, too — it’s a very commonly used combination in patients with resistance.

- Among those older than 65, a switch to BIC/FTC/TAF maintains viral suppression and is well tolerated. Raises my spirits to see the age threshold for “older” people with HIV to be moved up from 50 to 65!

- A compassionate use program offers injectable cabotegravir plus rilpivirine to people who cannot or will not take oral antiretrovirals. Of the 35 patients in this program, 28 were viremic — and hence received CAB/RPV treatment not as a switch-strategy, which is how it will be licensed. Still, a remarkable 63% of the total population achieved viral suppression despite enormous challenges.

At this point in these Really Rapid Reviews™, I often comment a bit on the host city’s cuisine, or sites, or weather, or something local. (Sharon Lewin says I captured Melbourne perfectly. Very proud of that comment.)

But since this was a virtual meeting, what can I discuss? The conference website? Acknowledging that it must be a huge challenge to put these meetings on this way, I confess to finding the AIDS 2020 site rather baffling. Fortunately, several people (including one of the conference chairs, Monica Gandhi) circulated brief tutorials. Here’s a nice guide, too.

Still, the search function was wonky, and I couldn’t figure out a way to share the URLs from the abstracts; as a result, the links in the above summary refer to outside sources.

And yes, it’s mostly NATAP, which remains the most reliable place to find conference results — despite a web design that hasn’t been updated since 1999 (my estimate). Thank you, Jules Levin and Mark Mascolini!

As usual, if I missed something important, put it in the comments section. Also — will we meet in person next year in Berlin? What do you think?