An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

July 13th, 2021

To First-Year ID Fellows, Incredible Gratitude and Respect — Especially for This Past Year

Two things happened earlier this month in most U.S. hospitals — the academic year started, and the number of people hospitalized with COVID-19 reached a low point not seen since the early phase of the pandemic.

(No, hospitalizations are not down everywhere. We ID docs are very much aware that COVID-19 isn’t over. But the national numbers are historically low — single digits in my hospital right now.)

The turn of the academic calendar means it’s a good time to express gratitude to the ID fellows who just finished their first year — especially this year, because unless you went through it yourself, I would argue that these past two years could not have been more difficult for these trainees. Historically so.

Let’s start with early 2020, the second half of senior medical residency for most ID fellows just completing their first year.

In normal, non-pandemic years, senior medical residency acts as a wonderful consolidation of all that’s learned in the preceding two years. With fewer clinical demands, senior residents can master the intricacies of inpatient medicine, teach on intern and medical student teams, handle their outpatient clinics, check out subspecialty electives, and participate in research projects. Senior residents also plan the next phase of their lives by either applying for fellowships or looking for a “real” job.

And yes, there’s a certain amount of gliding on cruise control. Plus all kinds of wonderful camaraderie, celebrations, and parties.

But 2020 offered nothing like this for senior medical residents. Here’s Dr. Eric Bressman’s account when he was Chief Medical Resident at Mt. Sinai Hospital, describing spring 2020 in New York:

Pretty soon we were just completely inundated, both at Sinai and Elmhurst, Elmhurst even more so. And while we were working a lot on the weekends, during the week it was all administrative in terms of completely remaking the structure of our floors, completely remaking the schedules of the residents to design a safer experience, both for the patients and for the residents. And we were pretty quickly working 24 hours [a day] to try and get that done, and I probably didn’t have a day off for two months.

Safe to say that there was no cruise control for these residents. Lots of unplanned inpatient coverage needed, especially in the ICUs. And the celebrations and parties? Prohibited for infection control reasons.

Plus remember this — for people who had applied to and then matched in ID, they chose ID before COVID-19 was even a thing. What had they signed up for?

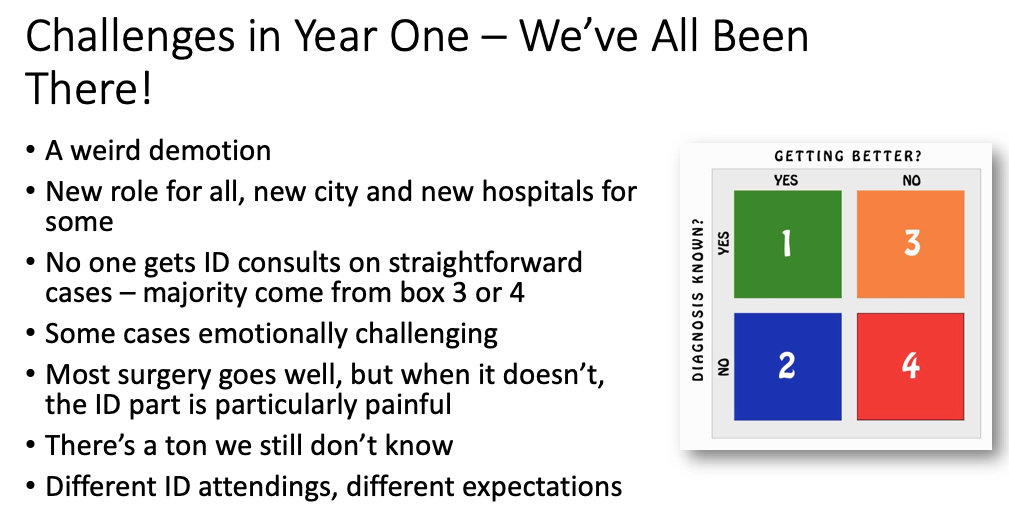

Yes, when they arrived to start fellowship last July, case numbers were down in some regions. But the first year of ID fellowship already has enormous challenges for multiple reasons, even without a pandemic. It’s hard! Rewarding too, but no piece of cake. A brief summary, including several items highlighted in a previous post:

I didn’t previously mention the “weird demotion,” but it’s true. July rolls around, and BAM! First-year ID fellows become beginners again. An internship redux, only now their entire clinical service consists of patients that medical and surgical teams can’t handle on their own (orange and red boxes in figure above). Challenging!

Then, as 2020 progressed, into the tricky mix of first-year ID fellowship came COVID-19 again.

In Boston, it was like a ghoul from a horror movie prematurely left for dead, only now back and just as strong and as scary as ever. COVID-19 wards reopened. ICUs again had critically ill patients, some of them shockingly young. Consults and pages about testing, treatment, and infection control all took off, including at night — but this time the rest of the hospital activities continued at the same time, in parallel. There was plenty of non-COVID-19 ID work to be done. Yikes.

I distinctly remember walking into our fellow work room one dark afternoon in December, two fellows sitting there nervously at their computers. For a bit, no words — then one said to me, quietly:

We all have COVID fear …

A completely understandable reaction to a completely terrifying situation, one we all shared. Only I strongly suspect, for reasons cited above, that the level of post-traumatic stress disorder experienced by first-year ID fellows seeing COVID-19 cases go up again probably clocked in at the 99th percentile or higher.

It was the combination of recapitulating their difficult senior residencies, the legitimate concerns about being overworked, the need to be the expert on a disease with still so many unknowns — plus the very real fear of personally catching the infection.

Which is why, when the first supplies of the vaccines became available to healthcare workers, and queries went out to prioritize vaccine recipients, the answer for us in ID was a no brainer. First-year ID fellows! Of course!

So thank you, just-graduated first-year fellows. You did an amazing job under such difficult circumstances. Enjoy both the relative calm that second-year brings with it, and this helpful owl trying to interpret a CT scan:

Trying to read a CT when radiologist read is pending pic.twitter.com/O919wIg2hK

— Adi (@IDdocAdi) July 11, 2021

July 1st, 2021

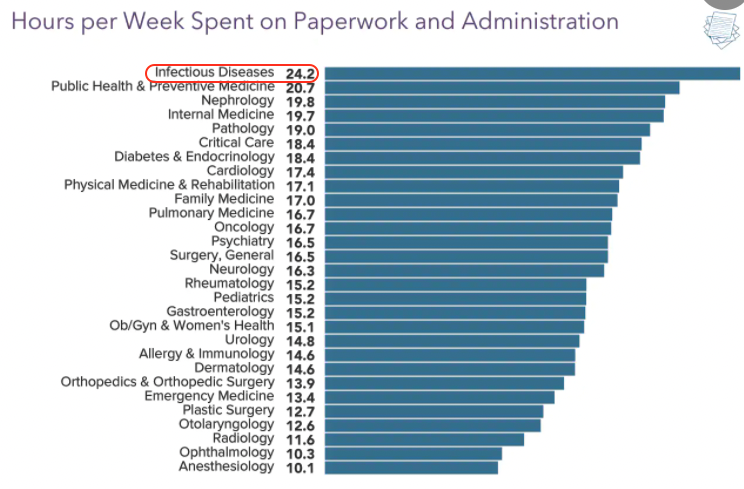

Five Reasons Why ID Doctors Are the Paperwork Champs

As they often do, the inquisitive folks over at Medscape polled doctors around the country on various topics.

This one hit home:

We're #1! https://t.co/4peKM1frWx pic.twitter.com/wwCrcXBrVI

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) June 17, 2021

Say what you will about Medscape’s methodology, or representativeness, or need for statistical analysis.

But we’re clearly #1 in the Paperwork and Administration category — and it’s not particularly close.

It’s also the very definition of a Pyrrhic victory — who wants this prize? — so let’s examine why this might be.

1. We take the best histories. We should celebrate this skill, as it is clearly our most important clinical procedure. After all, what other procedures do we generally do? That’s right, none.

But detailed histories take time — time to collect, and even more time to document.

Witness:

https://youtu.be/zHep6D_xxOo

These detailed histories, mind you, serve an important medical function and improve patient care — so often the critical missing piece of information arises in the process of collecting these data. I can much more strongly defend these histories than the common practice of cutting and pasting gobs of laboratory and other data into the note, the purpose of which is inversely proportional to its length.

Let the record show, however, that we were not put on this planet to provide the ideal source for a hospital discharge summary. Just imagine if we could collect royalties on every discharge summary that included a big chunk of an ID consult note — wow, we’d be golden.

2. We evaluate and manage complex patients — as a rule. Every doctor thinks their patients are the most complicated.

But since most straightforward ID problems are handled quite nicely by generalists, and no one gets an ID consult on patients who are doing well, the ID doctor’s rating of complexity is like the scale used on the WeRateDogs site:

This is Muffin. She hopes there’s still a spot on the Olympic team for her. Very confident this video is all they need to see. 14/10 pic.twitter.com/2uOyrUwJIx

— WeRateDogs (@dog_rates) June 29, 2021

That’s right — every case ranks at least an 11 on a 1-10 complexity score. Often higher. Like Muffin going for a swim up there. 14/10, go baby go.

In one of my favorite examples, I’ll cite again the landmark STOP-IT trial on the duration of antibiotic therapy for abdominal infections. Every ID specialist looked at the inclusion criteria — intraabdominal infection and adequate source control (emphasis mine) — and thought, “Who are these patients with adequate source control? Do they even exist?”

We have a resident rotating on our consult service right now who just did a consult on one such patient, and she couldn’t believe the complexity (certain details changed): The abdominal infection saga started in early-2020, and included a diverticular abscess, intestinal perforation, enterocutaneous fistulae, ventral hernia repairs, infected abdominal mesh, 8 separate admissions to three different hospitals, and innumerable polymicrobial cultures growing nearly every bacterial species in the MALDI-TOF database. Plus several different candida isolates.

“Adequate source control.” Ha ha ha.

3. We don’t give up. Shared, with permission, is this rant:

https://twitter.com/Boghuma/status/1407837071667040259?s=20

In the thread is further information that this application process started two months ago. Oh, and a later update — it’s still not resolved.

Who hasn’t faced the same thing when trying to get outpatient coverage for a novel antimicrobial? Omadacycline, anyone? Albendazole (the pricing of which is a true crime)? Tedizolid? Isavuconazole? I suspect we could fund an entire ID salary on the person-hours it has taken us to get our first few patients started on injectable cabotegravir-rilpivirine, which included a request for prescriber information that I didn’t even know existed.

And don’t get me started on clofazimine, which once upon a time was available by prescription, but now — just read about this painful process. Arghh.

COVID-19 brought with it an entire world of paperwork that previously didn’t exist, just like the virus SARS-CoV-2. Anyone who has tried getting monoclonal antibodies approved for inpatients with persistent COVID-19 probably thinks “EUA” stands for “Extra Unnecessary Activity.”

But we don’t give up. Because getting these obscure (and often frightfully expensive) drugs for people with difficult-to-treat infections is very much in our job description. So we do it.

4. We all have OCD — obsessive-compulsive disorder. I’ll never forget the sign-out I received from the graduating first-year fellow when starting my ID fellowship. A veritable tome, it weighed in at over a dozen single-spaced typed pages, each of them with the complete history, a detailed description of notable hospital events (surgeries, positive cultures, complications), antimicrobial courses (with doses), microbiology results, and assorted other factoids.

“I know it’s a lot,” she said, handing it to me. “But I’ve highlighted in yellow the things that need to be done today, and in blue those that might be important later.”

It was a color-coded masterpiece.

Look, we know we have a problem — and so does the rest of the medicine world, who gently tease us it about it periodically.

Here, take a look at the responses to this post:

What's more ID than writing an HPI that starts, "Briefly …"

… and then following it with a 1500 word note?

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) March 22, 2021

Many good responses, but this one truly captures it, from Dr. Joseph DeRose: “I do this as a prompt to tell myself to be concise … never works.”

Yep.

5. We don’t feel comfortable delegating work to others. I’ve thought about this one ever since my friend and neighbor, a thoracic surgeon, told me he had no trouble with our complex new electronic medical record.

“Barely look at it,” he said. “That’s what our PAs are for.”

Yes, he’s got a veritable army of support staff taking care of his patients — not just skilled PAs, but nurses, secretarial staff, scribes — and their responsibilities include note writing, prescription refills, prior approvals, insurance issues, filing, OR scheduling, patient transport, and likely also when to put new birdseed in his finch feeder.

No doubt this support he gets versus your typical ID doc is proportionate to the RVUs (otherwise known as RVU$) generated by an thoracotomy compared to a fever of unknown origin consultation. Still, the disparity remains quite stark.

But it’s not just that — often even when we ID doctors do have support staff to help us, we end up just doing things ourselves. I found one of my colleagues standing by the fax machine, in the process of sending a lengthy document to a skilled nursing facility so the staff there had the latest discharge summary on her patient. I asked her why she didn’t ask one of our (very nice) clinic staff to do it for her, and she looked at me as if I were some sort of prima donna physician, too elite to get his hands dirty using our ancient fax machine, which requires a hand-crank for power.

Yes, she’s as dedicated a doc as you could imagine — but is faxing documents a good example of a highly trained physician “practicing at the top of their license”?

So those are the Top 5 Reasons why ID is #1 when it comes to paperwork.

I’m sure there are others, but I don’t want to get all OCD about it!

June 14th, 2021

The Time for Hospitals to Require COVID-19 Vaccination Among Employees Is Now

Drs. Harry Meyer and Paul Parkman examine the rubella vaccine. National Library of Medicine.

Imagine you work at a hospital.

Patients come and go, admitted through the emergency room, or electively for surgery. Or they arrive for the day — maybe it’s an outpatient visit, or to receive chemotherapy or an infusion of biologic agents, or to undergo various imaging and other tests.

Some of them, of course, have weakened immune systems and won’t be fully protected by the COVID-19 vaccines. Others may not have received the vaccines based on poor access to healthcare or other social determinants.

Now imagine that you, healthcare worker, contracted COVID-19 because you’ve chosen not to be vaccinated. You feel well — in fact you are completely asymptomatic, blithely clicking the NO SYMPTOMS box in your hospital’s entry screen — but you’re in that brief period of being highly contagious.

And, as a result, you are the source of a COVID-19 transmission within the hospital to one or more of these vulnerable patients, and maybe some hospital coworkers (who could also be immunocompromised) as well.

How would that make you feel?

Importantly, the above chilling scenario is anything but hypothetical. An outbreak in a nursing home occured when one of the unvaccinated employees infected multiple residents and other staff. Even though 90% of the residents had been vaccinated, three of them died.

As cases continue to drop in the United States, we might need reminding that this is a highly contagious virus — even more so with the latest variants, which are 50% more transmissible than the original virus from China. Key graphic below, with estimated R0 for the increasingly dominant alpha and delta variants:

"The fact it has happened twice in 18 months, two lineages (Alpha and then Delta) each 50% more transmissible is a phenomenal amount of change"—@ArisKatzourakis https://t.co/A4M6dGfxSp

by @JamesTGallagher @bbchealth pic.twitter.com/PWvIiKYTVC— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) June 12, 2021

There is a solution, of course, one which would make the likelihood of in-hospital transmission to patients much less likely.

Hospitals can institute policies requiring that all employees be vaccinated.

Medical exemptions, of course, would be allowable. Some also would argue that documentation of prior infection would be sufficient — reinfection is rare. I’m fine with both, though do recommend vaccination for people with prior disease.

But what about the limbo “emergency use authorization” status of the vaccines? Shouldn’t we await full FDA approval? According to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, employers may require vaccines for onsite workers as a means of protecting the safety of others despite this status.

This approach of mandatory immunization follows the model of required influenza vaccination (already widely in place nationally), but is arguably much more important — COVID-19 is more lethal than the flu, and the vaccines are more effective. Such a win-win-win for the individual, the hospital, and for public health overall.

As a result, it’s a policy we ID doctors — especially infection preventionists — strongly endorse. That’s why I was ecstatic when hearing that Houston Methodist, Penn Medicine, and Johns Hopkins, among others, all had put such rules in place. Our hospital is considering similar action.

Penn Medicine staff articulated their rationale in a NEJM Perspective, entitled Incentives for Immunity — Strategies for Increasing Covid-19 Vaccine Uptake. They cite a systematic review showing that requiring vaccination for employment is the most effective strategy to increase vaccination rates.

Vaccine requirements have enormous potential to improve public health. We know that school immunization policies here in the United States have kept our outbreaks of vaccine preventable illnesses among children much less common than in other countries, and we’ve actually eliminated one scourge entirely:

With vaccination requirements, more than 90 percent of children are protected against devastating diseases like polio and measles. Through vaccination requirements, smallpox was eradicated from planet Earth.

With the caveat that those interested in the musings of me, an ID doctor, are likely to think similarly, it appears that most agree that this is the way to go — if not now, then after full FDA approval:

Hopkins, Penn, Houston Methodist hospitals (among others) require Covid19 vaccination for employees since they may come into contact with patients. Is this the right policy? https://t.co/A7HbZ04lkC

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) June 12, 2021

But not all agree. More than 100 employees of Houston Methodist sued the hospital, saying that the mandate forced them “to participate in an experimental vaccine trial as a condition for continued employment.”

This is nonsense — getting the vaccine is not participation “in an experimental vaccine trial” — and fortunately a federal judge agrees, and dismissed the lawsuit. I’m hopeful that this action will pave the way for many other healthcare facilities to institute similar policies.

The bottom line is that it is a privilege to be in the position of taking care of patients, and with that privilege comes the responsibility of keeping them as safe as possible.

And that means getting vaccinated.

June 1st, 2021

We’re Allowed to Say that Some COVID-19 Vaccines Are Better than Others, Right?

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Over on the CDC website, an amazing resource, there’s this statement about the COVID-19 vaccines:

The best COVID-19 vaccine is the first one that is available to you. Do not wait for a specific brand.

I certainly agreed with that comment back in late 2020 and early 2021, when demand for vaccines exceeded supply, and we faced record daily case numbers and a race against more transmissible variants, in particular B.1.1.7.

But fast-forward to today, and things COVID-19-wise in the United States have remarkably, wonderfully, changed. (Knocks wood.) Vaccine supply is plentiful. More than half the population has received at least one shot. Cases, hospitalizations, and deaths continue to decline.

Plus, we’ve got a much-expanded database on vaccine effectiveness and safety, in particular with the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna, and an emerging sense of the J&J vaccine as well. Is the CDC’s statement still true?

Let’s take a look at the three vaccines available to us right now, comparing them in various metrics.

Effectiveness. We were appropriately cautious about making cross-study comparisons between results of the Pfizer and Moderna phase 3 studies versus those from the J&J study — different seasons, different variants, different geographic locations, different protocols.

But let’s be blunt — a difference between 95% and 60–70% efficacy in preventing symptomatic disease is pretty large. Plus, now we have many population-based studies of the mRNA vaccines showing 90% or higher effectiveness in clinical practice. Effectiveness studies for the J&J vaccine are just starting to appear, and the data look quite similar to the results from the clinical trial — in other words, around 70% effective.

Safety. Data on the rare — but serious — syndrome of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia (TTS) linked to the J&J vaccine were updated at the latest ACIP meeting on May 12. There have now been 28 cases after nearly 9 million shots. The median age was 40 (range 18–59), with 22 women and 6 men, with the highest risk among women ages 30–39 (roughly 1 case for every 80,000 doses). Again, amazing work by our vaccine safety program in identifying this important safety signal.

The mRNA vaccines, meanwhile, have no confirmed cases of TTS among over 245 million doses administered. Those are extremely reassuring data. Yes, subjective side effects are more common with the mRNA vaccines than with the J&J vaccine, and CDC now is tracking reports of myocarditis among younger people receiving these vaccines — connection still not confirmed — but many of these myocarditis cases have been mild. Meanwhile, some of the TTS cases have led to permanent disability and even death.

Boosters. It’s the question everyone wants to know — when will we need booster shots? From they are inevitable since antibody titers decline to never since cellular immunity is forever, the honest response is that we just don’t know.

But, if antibody titers are a marker for when we’ll need boosters, this modeling study shows a correlation between antibody titers and protection, implying we’ll need them sooner after the J&J vaccine than the mRNA vaccines. Which would not be very surprising with a one-shot approach, would it?

Convenience. Here the J&J vaccine should be the clear winner, requiring only one shot, and also being easy to ship and store. When we first heard of this advantage, many of us assumed this would mean a far greater supply and availability of the J&J vaccine. However, this is currently not the case, at least not yet. Manufacturing of the mRNA vaccines has clearly accelerated, and they are widely available in many diverse locations.

These differences are stark enough that I posted this poll last week:

Hey #IDtwitter — the @CDCgov writes, "The best COVID-19 vaccine is the first one that is available to you." Maybe true before, but now we're lucky, there's ample supply. So if you're advising someone, what would you recommend?https://t.co/toX4HW8zt9

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) May 24, 2021

It seems that most agree with me that the mRNA vaccines are now preferred. If you have a treatment or vaccine that’s both more effective and safer, you don’t need to be a disease modeler to figure out which one is better.

In the comments to this poll, some cited the contrast between where we are currently in the United States, and the situation globally — which remains dire, and still warrants a “first vaccine available” strategy. I cannot stress this point enough.

Others mentioned the importance of patient choice. I acknowledge this is an important consideration for individual cases — someone might need to reach that magic 2-week protected threshold sooner, or not have the time to come back for a second dose. These reasons could be enough to justify going forward with the J&J vaccine preferentially.

However, if someone asked me what COVID-19 vaccine I’d recommend, based on what we know now, my answer would not be “whichever one you prefer” or “whichever one you are offered first” — especially if it were a 35-year-old woman.

It would be an mRNA vaccine.

May 25th, 2021

Yes, the Yankees Had a COVID-19 Outbreak Even Though They’re Vaccinated — Here’s Why

John Clarkson, Boston Beaneaters, 1887. Library of Congress.

Hey Paul, aren’t you going to write something about the Yankees and their COVID-19 outbreak? How did this happen, aren’t they vaccinated?

So asked several of my friends, family members, and colleagues — understandably. I’ve never been shy about my unabashed obsession with baseball, nor my lifelong fandom of this particular much-reviled professional team, though it does earn me some good-natured ribbing here in Boston.

(I came to it honestly, having grown up in New York. And for the record, they were horrible the year I started rooting for them — 9th place. Yes I’m old, and yes that was quite the Impossible Dream year for the Red Sox.)

So here’s what happened with the COVID-19 outbreak among the Yankees, in as few words as possible: Nine people tested positive (mostly coaches and staff, one player). One symptomatic, with mild illness. All vaccinated, all with the J&J vaccine.

How could this occur? After all, with the vaccines so effective, to have nine breakthrough cases seems downright freaky, a bioterrorism plot hatched by Red Sox fans. Or if not that, an act of divine retribution for years of being America’s Most Hated Team.

With the caveat that I don’t have any inside baseball knowledge (you got that joke, right?), here’s how this could happen:

- The source of infection was a highly contagious person. The outbreak likely followed the over-dispersion model of SARS-CoV-2 spread, meaning one person spread to several others, rather than multiple different transmissions — a “super spreader” event, only with everyone vaccinated. This most likely happened indoors, and could have been introduced to the team originally from someone not vaccinated — but we don’t know that.

- A more transmissible or resistant variant likely caused the outbreak. Though the J&J vaccine did reasonably well in preventing infection in regions with circulating variants, there was some decline in efficacy in South Africa and South America. While I hope someone is sequencing these cases, sometimes the amount of virus in vaccinated people who test positive is so low (especially in those who are asymptomatic) that sequencing fails.

- The vaccine storage, cold-chain, and lot numbers need to be checked. Sometimes errors in vaccine handling happen that make it less effective. As if we needed a reminder that we’re still in unusual times, remember that baseball teams normally aren’t in the business of giving vaccines — they could have made a mistake.

- The vaccine isn’t 100% effective. This is the J&J vaccine, remember — 60-70% effective in preventing symptomatic disease. And even the mRNA vaccines aren’t 100% effective, as shown by this nursing home outbreak. But they sure do prevent serious outcomes!

- Most of these cases wouldn’t have been detected in the “real world” at all. Testing strategies in professional sports and the entertainment industry are intense, a far cry from what we do in the community. They test like crazy, especially once a case occurs, and generally have been using PCR — which picks up even fragments of viral RNA.

This last testing point deserves emphasis, because with all that swabbing and saliva collection — one report cited three times a day! — there’s a decent chance this kind of “outbreak” happens frequently all around us, but we just don’t know about it.

Regardless, the vaccine and the testing program did what it was supposed to do, meaning prevented severe disease, detected cases early, and prevented broad spread within the team. Most of the media coverage of the outbreak mentioned this favorable outcome.

Here’s a nice example, with an appropriate metaphor:

Cases that would have been hospitalizations become colds, and symptomatic cases become asymptomatic. Most infections are avoided entirely. The vaccine works like a strong head wind from the outfield, turning homers into doubles and doubles into harmless fly outs.

Love that!

And if the Yankees have any needs for an ID doc … my baseball achievements may have ended on my high school team, but I know an awful lot about antibiotics.

May 17th, 2021

CDC’s Surprise Mask Policy — and What It Means Right Now for Me

Edvard Munch, The Sun, 1911.

Anyone else out there blindsided by the CDC’s announcement last week about masks?

Fully vaccinated people can resume activities without wearing a mask or physically distancing …

Jeepers, that was fast. Less than a month ago, I was having a conversation with my dog Louie about outdoor mask mandates, wondering when our town would drop this unnecessary (in my opinion) rule about how we live out in the fresh air — where we know SARS-CoV-2 transmission is exceedingly rare.

But now, all at once, no masks needed at all for vaccinated people? Not quite — there’s plenty of fine print:

… except where required by federal, state, local, tribal, or territorial laws, rules, and regulations, including local business and workplace guidance.

That means we’ll still see masks in hospitals and doctors’ offices. Planes, trains, buses, airports. And this incredibly important caveat for our immunocompromised patients is a reminder that they can’t rely on the vaccines to protect them:

Well said, @CDCgov. The whole thing, but have highlighted something particularly important that often gets missed. https://t.co/aiUOs5nu4K pic.twitter.com/3KaJldDTmo

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) May 13, 2021

I’d add that many will continue to wear masks in settings like the crowded Trader Joe’s in my neighborhood, regardless of the policies they (or other companies) institute. Let me ask you — in places with sufficient density of people in public indoor settings, with the vaccinated status of many still not known, and case numbers still at tens of thousands a day nationally, why not wear a mask?

That’s what people like me will do. (Not that you need reminding, but I’m an ID doctor, living in a very mask-friendly state.)

In this piece, Zeynep Tufekci argued for CDC’s holding out a bit longer before making this policy statement — along with setting benchmarks for case numbers before removing indoor mask-wearing in public for vaccinated people. Several others have commented that they thought the announcement was premature.

I get that. But since half the country thinks this action by CDC is too soon, and the other half too late, the CDC’s probably getting it about right, timing-wise. Remember, local jurisdictions can make their own rules, people who have been vaccinated can make their own decisions, and there is a deep hope that this action will encourage those who have not yet been vaccinated to do so — it’s a tangible benefit.

So what happens next nationally? Strongly suspect we’ll see a continued downward count of case numbers, even with less mask-wearing. This is the combined power of the vaccines, which have proven to be remarkably effective in real-world settings, the shift toward outdoor activities, and exponential decay — fewer people out there with COVID-19 means fewer opportunities for new infections, an amazingly strong force we saw in play last summer even before we had vaccines.

Look, even with far more testing, we’re already back to where we were last June, and it’s only mid-May:

The last time the US had <17,500 confirmed cases in a day was June 8, ~11 months ago, when the testing was 1/3rd as much as now.

The descent (exponential decay) continues pic.twitter.com/ehb2LHP6qb— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) May 17, 2021

Believe me, I know that COVID-19 is not yet over — new cases still are occurring, and still will occur. Some will be serious, especially in the unvaccinated or the immunosuppressed. Some others will be in vaccinated people, mostly linked to indoor transmissions, as they always have been.

Remember, with this virus — humility. Stay flexible. Respond to new data. Keep on vaccinating.

And cheer these great numbers!

May 10th, 2021

Goodbye, Physician’s First Watch — We’re Really Going to Miss You

WPA travel poster (1939) has nothing to do with this post, but I like it since everyone hates mosquitos, especially ID docs.

One of the great joys of life is working with great people, and for me, this includes frequent interactions with several skillful medical editors. They scan these posts for typos and awkward sentences, and warn me when I inadvertently include a copyrighted image or an inappropriate video.

They also worked, until recently, for Physician’s First Watch, which sent out daily emails highlighting the top stories in medicine — published papers, conference highlights, policy changes, new guidelines.

For practicing clinicians too busy to keep up with the voluminous medical literature and breaking news, this service was absolute gold — how else would an Infectious Diseases doctor learn about (yet another) negative vitamin D study? The latest on how to manage back pain in outpatients? Or understand that the USPSTF has come out with (yet another) recommendation against screening for a certain disease?

(Those USPSTF guys sure are tough. Wonder if you have to take a standardized skepticism test before joining this group, with only those scoring in the 99th percentile allowed in.)

That the First Watch newsletter came from a trusted source, with the appropriate references readily linked, only added to the value. You never felt like it was a thinly veiled marketing platform, or clickbait. Here’s What the Grouchy USPSTF Panel Does in Its Free Time — and You’ll Never Believe It.

Physician’s First Watch also kept me updated in my own field, Infectious Diseases — in particular advances outside of my primary areas of focus. Recent examples included a systematic assessment of delayed antibiotic prescribing in the outpatient setting and an observational study comparing amoxicillin-clavulanate and metronidazole plus a fluoroquinolone.

Alas, Physician’s First Watch ceased publication on April 29th — and the medical world mourns. Email from a Dr. Frank Domino, a primary care physician:

Hey Paul —

Why did NEJM stop First Watch? It was awesome! Kept me up to date better than anything, and I used it as a teaching tool with students all of the time.

Frank

We agree, Frank. It was regular breakfast table conversation fodder for both my wife (a practicing pediatrician) and me.

As I understand it, the decision was purely a business one, as the quality was always superb. But publishing in general, and medical publishing in particular, is going through a very unstable time. It’s no secret that many online and other “free” electronic endeavors have not been able to generate revenue from their content, a problem exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Here is a superb review of why some of these sites have either shifted to a subscription model or shut down entirely.

But one thing is clear, at least for now (looks over his shoulder) — I’m going to continue writing on this site. Am enormously grateful to NEJM Journal Watch for the opportunity to write this blog or column or newsletter, or whatever you want to call it. I also greatly appreciate all the regular readers, and comments, and suggestions, and feel like we’ve built a wonderful ID-oriented community that welcomes anyone interested, ID-trained or not.

For those who relied on Physician’s First Watch for notification about new posts, that’s not going to work anymore. But you can subscribe by entering your name and email address in the Subscribe box at the end of this post or in the column to the right, and confirming that you want a subscription — then shazam, just like magic, you’ll get an email when a new post appears. Don’t worry, we won’t share your name or email with anyone.

I’ll continue to cover the latest on ID, HIV, and while it’s still with us, (deep breath) COVID-19 — along with other general ID and non-ID topics, and the occasional silly digressions. Here’s a summary of the various things covered over the years.

Who knows? One of these days I might come up with a more interesting title — suggestions still welcome!

Subscribe to this blog!

May 3rd, 2021

Some Colleges Require COVID-19 Vaccination — Why Don’t They All?

Horse Feathers, 1932. Paramount Pictures.

Each time a college announces that it requires that students be immunized for COVID-19 to attend in-person classes or to live on campus, I do a little cheer. Sometimes it’s accompanied by a happy dance — especially when it’s right in my neighborhood.

Why?

Because ever since the pandemic started, carefully done epidemiologic studies consistently show that older teens and young adults have the highest incidence of infection.

This fact might be counterintuitive, since older people bear the disproportionate share of severe disease. As a result, the media quite regularly gets it wrong, by reporting each time when cases surge anew that “this time it’s different — it’s young adults.”

Nope. It’s always been younger adults. They just don’t get as sick. And during the first wave in early 2020, with testing severely limited, we could only test the sickest people — sometimes only those who came to the hospital. Infections in younger people went undiagnosed, since most cases were mild or asymptomatic.

But three key points about COVID-19 in young people should strongly favor mandatory college immunization. First, some young adults get quite sick indeed. Some have lengthy post-COVID symptoms that keep them out of school or work for weeks or months. Some get hospitalized. Some even die, with tragically so many years of life lost.

Second, outbreaks on college campuses can be large, disruptive, and enormously resource-intensive to control. The testing and infection control protocols vary from school to school, but all are costly in both time and dollars.

Finally, young adults with COVID-19 play a key role in perpetuating the epidemic. Mild disease is still contagious, of course, and communities with in-person higher education experienced an increase in COVID-19 incidence, suggesting that infections in students lead to transmissions both on campus and off.

Indeed, vaccinating college students may be a critical strategy in bringing the pandemic under control. Health economist Dr. Zoe McLaren summarized this benefit nicely in this thread:

Young people have a lot more power to end the pandemic than they might realize. Some modeling studies actually show that, under certain conditions, high vaccination rates of people 16-24 could end the pandemic more quickly than vaccinating the vulnerable. 5/8

— Zoë McLaren, Ph.D. (@ZoeMcLaren) March 21, 2021

She kindly referred me to this modeling study, which demonstrated the powerful public health benefits of vaccinating younger adults. Note that the effects would be even bigger than in the study, as the vaccines turned out to be more effective at blocking infection than the authors estimated at the time.

Some might wonder why the rate COVID-19 is so high in teens and young adults. But those who are parents of kids this age, or even better have an accurate memory of their 15-25-year-old self, will not be surprised. When you’re this age, socializing with friends isn’t just a leisure activity — it feels like breathing oxygen, necessary for survival. It’s during this socializing that we develop our identity, affiliations, and friendships, test our independence, and explore the broader world as an almost-adult.

Is it any surprise that this age group would have the hardest time with social distancing? While many of us older types, already paired-off or settled or both, haven’t dined out in months, a college student who starts a new semester in a dormitory or off-campus apartment isn’t likely to sit at home alone all semester, ordering groceries online and avoiding all group dining. And this doesn’t even get into classes, study sessions, sports, concerts, Greek life, or romance.

So what’s blocking the universal requirement for vaccination before on-campus classes or living? After all, don’t most universities require documentation of several immunizations already? Yes. COVID-19 is a far greater threat to personal and public health than many of these other vaccine-preventable illnesses.

One frequently cited obstacle is that these vaccines are not yet fully FDA-approved. True — but this is just a technicality:

Harvard Law professor Glenn Cohen, who teaches health law and bioethics, said there’s no legal reason colleges wouldn’t be allowed to require COVID-19 vaccinations. It makes no difference that the shots haven’t been given full approval, he said, noting that many colleges already require students to take coronavirus tests that are approved under the same FDA emergency authorization.

Already nearly 200 universities have issued a ruling requiring that students get a COVID-19 vaccine. Medical exemptions, of course, are permitted, but based on the safety profile of the vaccines, should be infrequent. (Thanks to Benjy Renton and his invaluable site for that link — he’s been providing terrific coverage of COVID-19 and higher education for months.)

So go for it, colleges and universities. Make the COVID-19 vaccine a requirement for on-campus learning and living, even offer it on-site for those who can’t get it at home. You have my 100% support.

Groucho, Harpo, Chico, and Zeppo agree.

April 25th, 2021

The Decision on the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 Vaccine Surprised Me — Here’s Why

The “pause” on the one-shot Johnson & Johnson (J&J) COVID-19 vaccine is over. Based on a further review of safety data that occurred on April 23, both the CDC and the FDA said the vaccine may resume here in the U.S., provided the label includes a warning about a serious, but rare, side effect — thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS).

I confess this decision surprised me. My hunch was that they would advise limiting the vaccine in the U.S. to women older than 50, with no age criterion for men. Instead, it’s now available for all.

This was no doubt a tricky decision, one reflected in the 10-4 vote of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). When experts disagree, I find it useful to list those things we all can agree on:

- These are not your typical blood clots. TTS bears a strong resemblance to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), with low platelets and development of antibodies to platelet factor 4. This “consumptive coagulopathy” has distinctive clinical features, is challenging to manage, and should not be treated with heparin — which can worsen the disease.

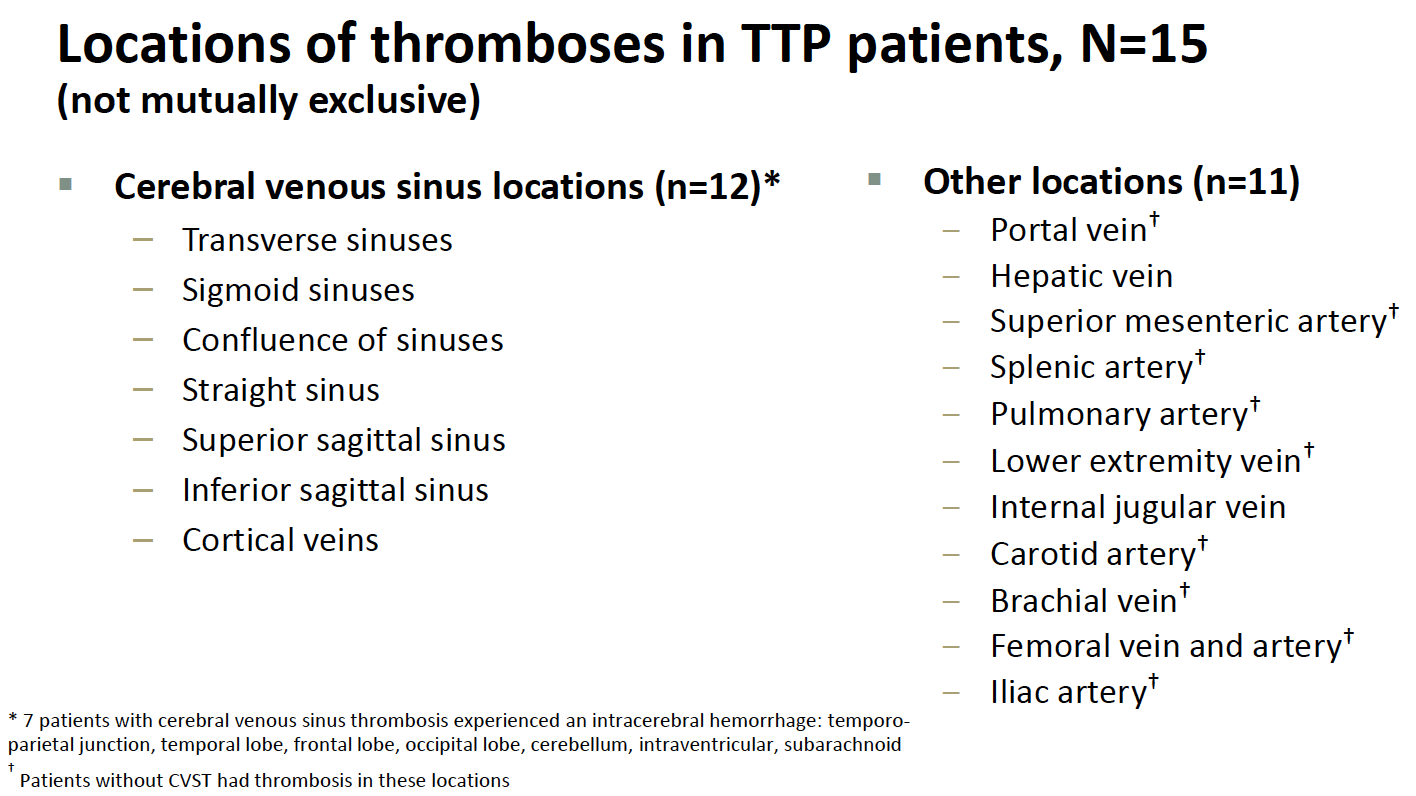

- The cases are very serious. Venous thrombotic events vary widely in severity; the clots in these TTS cases occurred in particularly bad anatomic locations, most commonly in the cerebral venous sinuses. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) can lead to permanent neurologic disability, require intensive care, or even be fatal. In the TTS cases, clots also occurred in other sites, and in the arterial system. From Friday’s ACIP meeting:

- They are rare. Nearly 8 million people have received the vaccine, and 15 of these distinctive clotting events occurred, for a rate of around 1 case per 500,000 people vaccinated. Additional cases may come to light, and apparently, around 10 are under investigation.

- The risk is higher in younger women. Thus far, all the cases occurring since the emergency use authorization (EUA) have been in women. The median age was 37 years (range 18–59). For women aged 18 to 49 years, the estimated TTS rate is approximately 1 per 140,000 doses — and potentially higher if more cases occur in this age group among the 10 or so being investigated. Plus, in hindsight, a 25-year-old man likely had a similar syndrome during the clinical trial.

- They occurred shortly after the vaccine. Median time to symptom onset was 8 days (range 6–15 days).

- Similar thrombotic events occurred with the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. This adverse effect is the primary reason some countries slowed the rollout of this vaccine globally or limited who should receive it. (The vaccine is not used in the U.S.) With the AstraZeneca vaccine, a broader demographic appears to be at risk. Both vaccines use an adenovirus vector strategy to deliver the SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen.

- No cases of TTS have yet occurred with the mRNA vaccines. While thrombotic events have been reported after the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines, none of the cases had low platelets or the other distinctive characteristics of TTS. Given the nearly 200 million doses of these vaccines already administered in the U.S. — with millions more globally — these are highly reassuring safety data.

- The J&J vaccine has several favorable characteristics. As a one-shot vaccine with less stringent storage requirements than the mRNA vaccines, it theoretically would be easier to give to a broader — and sometimes disproportionately at-risk — population. Specifically cited in the ACIP meeting included the homeless, rural residents, people in prison, disabled, homebound, or those with limited access to healthcare.

- We have a sufficient supply of mRNA vaccines to vaccinate all eligible adults in the United States. Given what India is going through right now, just writing this breaks my heart — but it’s true and must be considered in the risk calculation of using the J&J vaccine. Hence while the favorable characteristics of the J&J vaccine would make vaccinating the U.S. population easier, it may not be required.

- COVID-19 case numbers are falling in most of the United States. Even Michigan, the state with the recent marked surge, is fortunately now showing a sharp decline in case numbers. Again, this is critical when thinking about the risk calculation for someone choosing whether to be vaccinated and when.

The process by which safety issues come to light with these vaccines is truly impressive. These rare events triggered a thorough investigation, one in full public view with all the data shared. That’s a real win.

But let’s now consider an otherwise healthy young woman who wants a COVID-19 vaccine.

Give the availability of the mRNA vaccines, the falling case numbers nationally (and hence her reduced risk of disease), and the rare — but extremely serious — side effect of TTS that might occur with the J&J vaccine, under what possible circumstances should the J&J vaccine be the recommended approach?

If it’s a matter of convenience, I’d say it’s worth spending the time educating about how to get the two shots and avoiding the small risk.

If it’s a matter of lack of mRNA vaccine availability, I’d say fix the supply issue or outline where an mRNA vaccine is available.

But now? It’s possible that this young healthy woman might end up getting the J&J vaccine. And while the odds are overwhelmingly in her favor that everything will be fine, in practice, this would be giving a vaccine with a recognized safety issue when two highly effective and safe alternatives exists.

And the warning? I worry about women who lack the medical literacy to fully understand it, or the cultural authority to question what is being offered to them, or the forthrightness to request alternatives — or all of the above.

And that can’t be right.

April 19th, 2021

Is It Time to Eliminate Outdoor Mask Mandates?

Louie checks out our local town policies.

I do the morning dog walk in our house. And every day, I put on a mask before going out, just as I have since March of last year.

As the data accumulate on the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, it’s definitely time to ask this question — why am I still doing this? After all, it’s just Louie and me — and even he’s wondering.

It’s generated some interesting dialogue between the two of us:

Why are you doing that? he asks me each morning. Who are you protecting?

Good questions, Louie!

It’s true, I’ll briefly pass an occasional person on the street or sidewalk. But they’re not going to get COVID from me, or the reverse. That’s not how this works.

Even if I, as a fully vaccinated person, were asymptomatically carrying SARS-CoV-2 — already exceedingly unlikely on any given day — the virus would be rapidly diluted by the extraordinary ventilation conferred by just being outside.

And while the vaccines aren’t 100% protective of me — nothing is, sports fans — they are amazingly good. Got to love these recent CDC data, interpreted by indefatigable COVID-19 optimist Dr. Monica Gandhi:

When CDC says <1% vaccine breakthroughs, let's be specific & say 0.008%. And in terms of severe disease, 0.0005% and in terms of deaths, 0.0001%. And Dr. Fauci said severe disease in elderly with other health problems to NPR. Reduce hesitancy by optimismhttps://t.co/mYLQ7G8psi https://t.co/MsQJwGPtkT

— Monica Gandhi MD, MPH (@MonicaGandhi9) April 17, 2021

With COVID-19, the most intensely studied viral respiratory tract infection in over a century, it’s worth emphasizing that clear documentation of outdoor transmission has been a challenge — and it’s not for lack of trying. In such rare cases, it’s often impossible to disentangle the indoor activities accompanying the outdoor events as contributing to the risk.

Or the people were crowded together outside, facing each other and interacting. Or exercising together and breathing heavily.

Transmissions do not take place between solitary individuals going for a walk, transiently passing each other on the street, a hiking trail, or a jogging track. That biker who whizzes by without a mask poses no danger to us, at least from a resipiratory virus perspective. Read more about the safety of being outside in this excellent piece by Shannon Palus, which also questions the need for masking outside — generating quite the heated commentary, as I anticipate this post will also.

But what about the community solidarity engendered by wearing a mask outside in public? Isn’t this worth something? A way of showing that I’m 100% part of Team Mask?

Maybe — certainly there’s a strong component of this messaging among the highly adherent mask wearers here in Boston. But this performative aspect of outdoor mask-wearing has a downside, too.

You might think you need to wear a mask while walking me in the morning to set a good example for others, said Louie the other day.

But really you might be misleading people about how the virus is transmitted.

Wise words, dog of mine! (He’s very articulate.)

Here’s a bold proposal — let’s make public policy based on our best understanding of the science of SARS-CoV-2 transmission:

Dangerous — crowded indoor spaces with poor ventilation, in particular with unmasked individuals talking, shouting, singing. Wear a well-fitted mask until case numbers are down and more people are vaccinated.

Safe — outdoors, especially while distanced. Masks only needed for lengthy interactions with others at close distance.

Some might wonder if this is too nuanced a message — the “people will get confused” argument.

Give them more credit than that, says Louie. If I can understand it — and I’m a dog — so can they.

He’s got a point, it’s not that hard. We’ve learned so much since the terrifying days early in the pandemic — why not share what we’ve learned and eliminate mandates that no longer make sense?

To wrap up, Zeynep Tufekci kindly shared her thoughts on this issue. She’s been fighting something she’s called “beach scolding” for over a year now. It’s when public health officials and the media shame people or even worse prohibit outdoor activities — when they should be encouraging them since they’re so much safer. Examples — the dreaded yellow police tape outside the park or on the benches, the swings removed from the playground, the beaches and lakeside trails closed.

In a way, it relates to outdoor mask mandates:

Sometimes people invoke the precautionary principle or what’s the downside argument to argue for universal masking outdoors. However, the precautionary principle is not necessarily appropriate after a whole year of epidemiological data showing little to no transmission outdoors outside of sustained close contact: precaution is what we do when we don’t know the answer, not something we invoke to continue doing things on autopilot.

Plus, there is a very important downside that’s not being considered sufficiently: by mandating or normalizing masks outdoors at all times, we are miscommunicating about the real risk factors—indoors, especially if they are crowded and poorly-ventilated—which means that even a full year after the pandemic, people are not being properly informed about where and how they should increase their vigilance.

It’s fine to tell people to continue wearing masks outside especially if they are unvaccinated and are about to engage in a sustained interaction at close distance, especially if it involves higher aerosol emitting activities like talking, yelling or singing, but it’s time for the excessive masking outdoors, and especially mandates, to go.

Bravo. Looking forward to seeing more outdoor faces soon.