An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

December 6th, 2021

Omicron and the Quest for “Negative Capability”

John Keats, portrait by Joseph Severn

Wow, that was quite the depressing post-holiday week in ID Land.

For that, we can thank the new villainous variant, Omicron, which arrived ironically just as most of us here in the United States sat down to celebrate something approaching a “normal” Thanksgiving for the first time in two years.

Oh yes indeed, thank you very much for joining us, Omicron. How do you like your cranberry sauce?

Talk about an unwelcome guest at the party.

Here in Boston, like many parts of the northern U.S. and Europe, the arrival of Omicron joins a very active pandemic still dominated by Delta. It’s not like we needed this new highly transmissible, immune-evasive version of SARS-CoV-2 to jolt our holiday season. The current version (Delta) of the world’s least-favorite virus remains quite capable of straining hospital resources; disrupting school, work, and travel; and putting us all on edge.

Sigh.

Meanwhile, everyone wants to know what happens next. I totally get it — the pandemic has been with us for what feels like an eternity, and an accurate prediction would be highly valuable for all. Since the news broke about Omicron — has it really been less than 2 weeks? — these predictions have come in two vastly different flavors.

First the doom and gloom:

It’s highly transmissible … and very vaccine evasive … lots of reinfections … so many mutations … case rates skyrocketing in South Africa, fastest increase ever … super-spreader events among fully vaccinated … kids getting hospitalized … already it’s on all continents … some monoclonal antibodies won’t work … spike gene target failure, whatever that means … >30% test positivity in some parts of South Africa … transmission with minimal contact in Hong Kong … how do you even pronounce this stupid word …

Or alternatively, maybe it’s not so bad after all:

Cases are mostly mild … hospitalization rate is lower than with Delta … our cellular immunity (from vaccines or prior infection) will save us from severe disease … Omicron may have genetic material from common cold coronaviruses, and we live with those, don’t we? … maybe the mutations will make it less virulent … the vaccine manufacturers are tweaking the vaccines to respond … our PCRs and rapid antigen tests still work … some monoclonals (sotrovimab, AZD7442) should still be effective … antivirals are coming soon … this will be how the pandemic finally plays out, a mild disease leading to broad immunity …

So which one is it? Are we headed back to square one, and soon will be decontaminating our groceries and packages again? Or are we close to the pandemic endgame, optimistically predicted before, but this time we really mean it?

The reality is undoubtedly somewhere between these two extremes. We can’t possibly be going back to square one; we know so much about this virus by now:

I absolutely hate this title in @TheAtlantic

To say we know nothing completely neglects the research, learnings and experience of past 2 yrs.

We know SO much about Omicron.

Relative to ALL we DO KNOW, the things we don’t know are minor

— Michael Mina (@michaelmina_lab) December 4, 2021

On the other hand, Omicron could very well pose quite the challenge, as it appears to have qualities similar to Delta and has so many spike protein mutations that vaccine scientists gasped when they first saw the structure. In other words, beware overly optimistic predictions about Omicron just as much as doomsday scenarios.

Where does that leave us? At times of great uncertainty, I try to channel the teaching from a memorable college English literature course on Romantic poetry. (I know, pretentious — but stay with me on this one.) The great poet John Keats, writing to a friend, cited an ideal state of mind for the creative process, one he called “negative capability.”

Despite the word negative, he meant it in a quite positive way, as it describes a person “capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

Not surprisingly, I’m not the first person, and not even the first doctor, to think of this important quality while trying to navigate unknowns while living through a pandemic. Indiana University’s Dr. Richard Gunderman (who has way more titles than I) wrote earlier this year a highly pertinent essay:

Rather than coming to an immediate conclusion about an event, idea or person, Keats advises resting in doubt and continuing to pay attention and probe in order to understand it more completely … Negative capability also testifies to the importance of humility, which Keats described as a “capability of submission.” As Socrates indicates in Plato’s “Apology,” the people least likely to learn anything new are the ones who think they already know it all.

I’ve tried this negative capability approach this past week with the deluge of questions sent my way by worried colleagues, friends, and family.

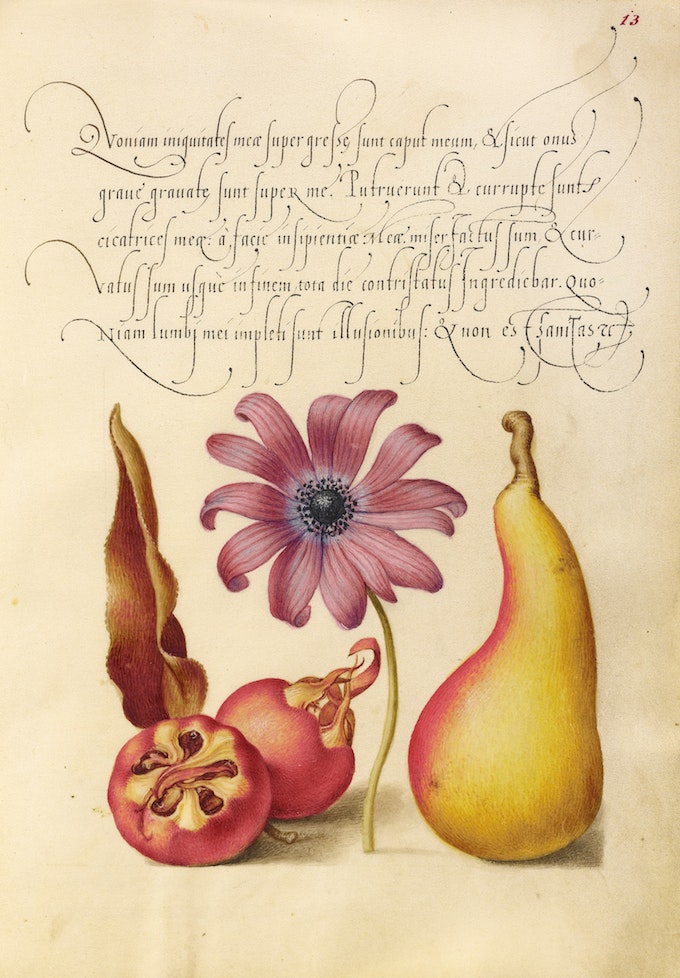

Here’s a brief personal example, posted with permission:

Maybe it’s a copout, but for questions like this, there is no 100% correct, data-driven, or accurate answer. What would you say?

And how are you doing, folks?

November 23rd, 2021

Gratitude for 40 Years of Progress in HIV Care and Research

The Chap Book — Thanksgiving, Will H Bradley, 1895.

I was working with one of our outstanding senior ID fellows in clinic last week, and she presented the case she’d just seen, a 54-year-old man with HIV (certain details changed for confidentiality):

Will is doing great on [fill in one-pill daily regimen], missing no doses. He’s having some difficulty with sleep (his wife says he snores all night if he doesn’t use CPAP), not really sticking to his low-salt diet, and back pain. He agreed to get the flu shot. He’s due for labs.

In other words, this was your very typical HIV follow-up visit. Someone quite brilliantly likened them to well-baby visits for us ID doctors, because they often have zero active ID issues. It’s all about health maintenance.

(The flu shot doesn’t count as an active ID issue.)

Why even bring this up? Because this ID fellow had the wisdom to add, in an aside:

It’s hard to believe that just two years ago his CD4 cell count was 6, his viral load was over a million, and he was hospitalized with PCP.

Yes, it’s hard to believe. And it is amazing.

Remember, the median survival for a person like this with a serious HIV-related opportunistic infection in the 1980s was roughly 1 year. And today, this man not only has an excellent prognosis, but his active medical issues are the bread-and-butter of any primary care practice — sleep apnea, hypertension, low back pain, immunizations.

Thanksgiving is this week, and the best part of this holiday is that we express thanks for the good things that have come our way over the past year. In this spirit, I’ve typically written an ID-themed “gratitude” post in honor of this annual Thursday day off from work. It’s a fun column to write, and it’s interesting to look back and see the progress we’ve made and what we cheered about — especially in the pre-pandemic times. Sigh.

But this year, in honor of the 40th year since the publication of the first cases of AIDS, and because someone invited me to give a “History of HIV” talk, and because World AIDS Day just happens to be December 1, I’m going with just this biggie — the medical miracle of HIV care and research over the past 4 decades.

Here’s the talk I gave, Part 1, which covers the first twenty years:

The "History of HIV" talk I gave last week actually has this title, which I don't think is an overstatement. Posting it now with gratitude, just in time for Thanksgiving (my favorite holiday — the gratitude and family part).

(Part 1 thread)

1/x pic.twitter.com/120HGtFKEh— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) November 20, 2021

Part 2 is here, bringing us up to date, and finishing with a link to the full slide set — go ahead and download to your heart’s content. Both Parts 1 and 2 include content quite miraculous by any standards.

Grateful for this progress!

And grateful also for Saturday Night Live — a show which, despite its age, can still hit it out of the park* every so often.

Happy Thanksgiving!

*”Hit it out of the park”: To do or perform something extraordinarily well.

November 12th, 2021

Time to Simplify the COVID-19 Vaccine Policy — Authorize a Booster Dose for Anyone Who Wants One

Medlar, Poppy Anemone, and Pear. From The Model Book of Calligraphy (1561–1596).

At this point in the post-vaccine era of the pandemic, we all know people who have had COVID-19 despite being fully vaccinated. Patients, coworkers, family, friends.

The reason these breakthroughs are so common is now obvious — our initial vaccine strategies did not provide durable protection against infection. And recognition of this fact prompted the FDA and CDC to recommend a booster dose for people at high risk for severe COVID-19, and for people at high risk for exposure to the virus. Six months after the second dose is the recommended schedule.

Based on my occupation, I’m one such eligible person. (Thank you, Dr. Walensky.) But shouldn’t everyone have access to this benefit? I’d strongly argue yes.

Because at this point, it’s not just one study showing the vaccines are losing their effectiveness over time — it’s multiple studies, conducted all around the world in highly diverse settings and using different vaccines. As an example, let’s go with this large recently published paper because the effectiveness curves tell the story so clearly:

Important paper, just published @ScienceMagazine, on waning vaccine effectiveness among >780,000 US Veterans over time and during the Delta wave. Across all ages; J&J vaccine had the most decline; reduction protection vs deaths too (Figure at right) https://t.co/onRQY9XAl0 pic.twitter.com/nj6zG3Hedw

— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) November 4, 2021

While the vaccines continue to be way better than no vaccine in prevention of serious COVID-19, hospitalization, and death, they’re slowly losing their effectiveness in these metrics too — especially among high-risk individuals.

Let’s also state the obvious:

Some people who get “mild” breakthrough infections get pretty sick, and feel lousy.

They have fevers, chills, cough. They lose their sense of smell and taste. They are profoundly fatigued. They’re out of work, or school, and have to isolate from their family and friends.

In other words, though classified as “mild” cases for epidemiologic purposes, they don’t feel so mild to people who get them.

In addition, a symptomatic case — breakthrough or not — can pass the virus on to others, which is especially worrisome for the not insignificant proportion of the population who are immunocompromised and don’t get full protection from the vaccines.

Which is why, while watching our vaccine experts and public health officials and the FDA and the vaccine manufacturers debate over who should and who should not be eligible for a 3rd dose of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, I’ve come to the straightforward conclusion that it should be any adult who wants one.

And I’d recommend that strategy for pretty much 100% of people who ask me what they should do — just as I’d advise an annual flu shot. After all, influenza also causes a nasty respiratory viral infection that most of the time does not lead to hospitalization or death. We still want to prevent the flu in young healthy people, don’t we?

Another benefit of advising boosters for all is that it will simplify the messaging about what we advise our patients, which is now way too convoluted. Allow me to quote (with permission) primary care physician Dr. Lucy McBride, who expressed frustration with the conflicting messages she’s been getting from the press and the CDC. She wonders what to tell her booster-ineligible patients now:

My concern is over the messaging and about the lack of clarity from CDC about what our overall goals are. I think it would improve trust in our public health institutions if they just came out and said, “Look – the vaccines still work great in preventing hospitalization and death, but we are worried about rising case numbers in the upcoming winter months and would like to reduce infections as much as possible.”

Agree 100%.

Some worry that authorizing boosters for all locks us in to repeated cycles of COVID-19 vaccination in an endless cycle of shots. But the reality is we just don’t know enough yet to make this statement. It could be that just this third shot is required for durable protection in most people. Or, alternatively, that periodic boosters will be required. Or something in between, based on community risk of disease, age, other risk factors, or a simple test to assess who is protected and who isn’t, or some other metric.

In short, we just don’t know — best to acknowledge that up front.

Additionally, some argue that giving a third dose distracts us from getting the unvaccinated people their first dose, or that doing so depletes the vaccine supply from global distribution to places that have limited access, or that this will increase vaccine hesitancy, or that some very small fraction of those who get vaccinated will have an adverse event, or that there are other non-policy prevention strategies that need reinforcement.

These are legitimate points to raise (artfully done by colleagues of mine) in discussions about where to focus our efforts in public health. We should welcome these debates, but not lose sight of the fact that these efforts can be done in parallel. Continuing to advocate for first-time vaccination for the unvaccinated and simultaneously offering boosters to adults are not strategies that conflict. California and Colorado already have adopted this approach.

So as we head into the winter, with cases increasing again — and Europe providing a potential warning of what we’ll be seeing soon in the USA — it’s time to just make these third doses available to all who want them.

Because getting this viral infection stinks. And preventing it is in everyone’s best interest.

October 31st, 2021

Interesting and Important Studies from IAS 2021 and IDWeek That Caught My Eye

Vintage Halloween postcard, 1913.

As noted in my previous post, attending virtual meetings poses some serious challenges.

The biggest obstacle: trying to do one’s regular job while periodically checking in (or more likely not checking in) on the meeting. And while I might have been able to pull off some Really Rapid Reviews© after a few virtual meetings, not so for the last two.

So instead, I’ve packaged 2 into 1, hoping this gives you sufficient value for your blog-reading dollar, lack of really rapidness notwithstanding.

Here, then, are some highlights from these two meetings, in a not-so-rapid (but I hope still interesting) review. The International AIDS Society (IAS) 2021 took place in July, IDWeek in early October.

As usual, but even more so now with virtual attendance, I’m bound to miss some important studies. Let me know in the comments what those might have been.

IAS 2021 is first up:

Single high-dose liposomal amphotericin-based treatment for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis is just as effective and less toxic than standard of care. This devilishly difficult-to-treat opportunistic infection continues to take a major toll globally, in particular in Sub-Saharan Africa, where this study (called Ambition-cm) took place. The comparator arm (daily amphotericin for a week with 5FC) is both less convenient and has more side effects. Two questions: 1) Can we make liposomal amphotericin and 5FC more widely available? 2) Does this study have implications for us here, where we use two weeks of induction amphotericin and 5FC?

PrEP failures with TDF/FTC may have drug resistance at HIV diagnosis: While the title of the abstract cites “High rates of drug resistance …”, the actual infection incidence was reassuringly rare. This study was done in Africa, giving us a far different view of PrEP than here — 75% women. Out of over 100,000 PrEP users, HIV was diagnosed in 208, and 27 had resistance mutations. Note the higher than expected incidence of K65R, probably because of subtype C virus, along with the transmitted NNRTI mutations.

No selection of INSTI resistance among women in HPTN 084 who acquired HIV while receiving cabotegravir. Good news, and the results contrast with the small rate of resistance seen in HPTN 084 among MSM. One very challenging HIV diagnosis occurred in a woman who had (in retrospect) very early acute HIV (detectable virus but below 40 copies/mL), was randomized to cabotegravir, then had viral suppression and no seroconversion until week 33 of the study. Once this gets into clinical practice, assessments for HIV breakthrough will be challenging! 35/36 of those in the TDF/FTC arm who failed PrEP had suboptimal adherence.

On-demand TDF/FTC PrEP just as effective as daily PrEP among MSM in China. Analogous to the PREVENIR study, here the participants could choose how they wished to take the PrEP — daily or with the 2-1-1 on-demand strategy. In other words, the study was not randomized. An interesting observation — they enrolled MSM who chose not to go on PrEP at all; perhaps not surprisingly, they had the highest HIV incidence.

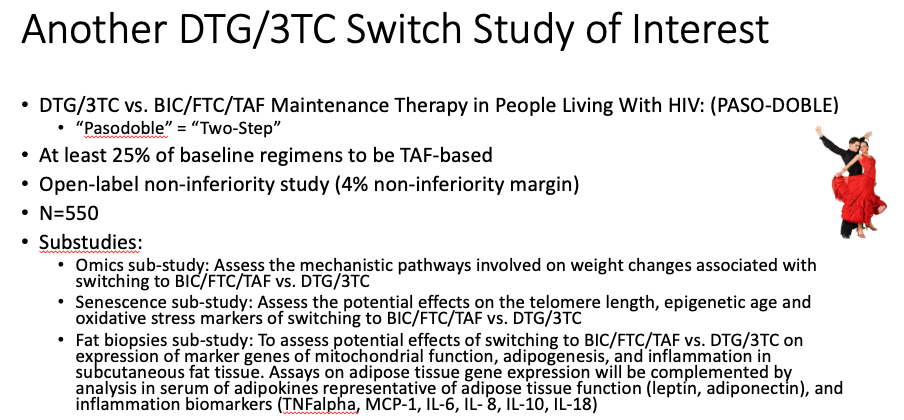

DTG/3TC maintains viral suppression in patients with a variety of baseline regimens. Unlike the TANGO study, where all participants were on TAF-based ART, in this study (called SALSA) they could be on any standard ART regimen, provided no history of treatment failure or resistance. The results demonstrate again that DTG/3TC is clearly a safe strategy virologically for this population. Note that there was more weight gain in the switch arm, likely because around half the baseline regimens included TDF (see first summary from IDWeek, below, for an explanation). An ongoing study — called PASO-DOBLE, get it? — will investigate whether maintenance therapy with DTG/3TC offers objective benefits over BIC/FTC/TAF, such as improvements in metabolic, bone, and various aging outcomes. Here’s a slide summary I made of that study, including the requisite dancers!

Lenacapavir as a subcutaneous injection every 6 months in treatment-naive patients achieves high rate of viral suppression at week 16. There were several different strategies in this phase 2 study which ultimately include two-drug maintenance, but the most novel were those that included lenacapavir given subcutaneously every 6 months (after an oral lead-in) with TAF/FTC. Over 90% had virologic suppression at week 16 (a planned interim analysis); BIC/FTC/TAF had 100%. One case of treatment-emergent resistance to both lenacapavir and FTC occurred in a participant who started treatment with a baseline viral load just over 100,000 cop/mL, implying that the resistance barrier to this novel drug isn’t as high as second-generation INSTIs.

No apparent worsening of outcomes from COVID-19 among people with HIV. This registry-based study included 21,528 hospitalizations, out of which 220 were people with HIV. Given the gazillion studies that have looked at this issue, it’s reassuring to note that not all demonstrate that HIV is a risk factor for more severe COVID-19 disease. My hunch? If you take our healthiest PWH (on ART, viral suppression), and carefully control for demographic factors and comorbidities known to worsen COVID-19, there won’t be much of an effect, if any, of having HIV.

Giving ART to “blipping” HIV controllers improves some immunologic markers. In this observational analysis of 301 controllers followed for a median of nearly 15 years, 90 started ART for various reasons — 83 with viremic “blips” before starting, and 7 with always undetectable viral loads. For those in the former group (the “blipping controllers”), ART led to reduced activated CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes and total CD8 T cells, and increased CD4/CD8 ratio but did not increase the CD4 cell count. No changes were observed in those who were always undetectable. Whether to treat people with this virologic phenotype remains one of the truly unanswered questions in HIV today.

Patients with a history of K65R from prior virologic failure and currently suppressed on ART switched successfully to BIC/FTC/TAF. The study included 71 people, half of whom also had M184V (hence resistance to both tenofovir and FTC). Viral suppression has been maintained in all of them now followed for a median duration of 47 weeks. These results are perhaps not surprising given the results of the NADIA study with TDF/3TC + DTG in people with treatment failure (many of whom had K65R), but they are reassuring to see nonetheless with this slightly different integrase inhibitor. My colleague Serena Koenig is studying this strategy in a randomized clinical trial being done right now in Haiti. Isn’t it remarkable how NRTIs retain activity even after genotypic (and high-level phenotypic) resistance?

Shifting now to IDWeek, with a few HIV and in particular COVID-19 studies of note:

A meta-analysis of seven clinical trials in 19,359 HIV-negative people shows that TDF is associated with weight loss. The strength of this comprehensive study is that the control arms received placebo, and that any “return to health” (which leads to weight gain) from treatment of HIV is excluded. The mechanism by which TDF induces weight loss is not clear, but we should definitely counsel our patients that discontinuing this drug may lead to weight gain. Some big questions remain — why does TDF do this more in some people than others? What is the mechanism? Is it harmful or salutatory? And — not relevant here, but clearly the case — why is the effect strongest when TDF is given with EFV?

Antibody responses to COVID-19 vaccines may be impaired in some people with HIV. Leading predictors of a good response were CD4 cell count (higher better), suppressed HIV RNA (suppressed better than viremic), and which vaccine was given — mRNA-1273 (Moderna) did better than BNT162b2 (Pfizer).

Another dual monoclonal antibody treatment reduces the risk of hospitalization and/or death in outpatients with COVID-19. The antibodies are BRII-196 and BRII-198, and the effect was in line with other treatments — a 78% reduction in risk. Provided there is no viral escape, I suspect the distinguishing characteristics of these various treatments will be their pharmacologic properties — half-life, formulations, mode of administration, cost. If that’s not enough for you …

Regdanvimab reduced the risk of hospitalization in high-risk outpatients with COVID-19. Hospitalizations occurred in 4.0% of the treatment group, and 8.7% receiving placebo, a 70% reduction in risk. (Amazing how consistent these results are.) Apparently regdanvimab binds to a different location in the spike protein than the other monoclonals.

AZD7442 (Tixagevimab/Cilgavimab) given as pre-exposure prophylaxis to high-risk outpatients significantly reduced the risk of acquiring symptomatic COVID-19. After 83 weeks of follow-up, only 8/3460 (0.2%) of the AZD7442 group vs. 7/1737 (1.0%) of those receiving placebo developed COVID-19, a 77% reduction in risk. Importantly, the study population was not vaccinated, and only 4% were high-risk based on being immunocompromised. Nonetheless, the results strongly suggest that AZD7442 — given as two 1.5 ml IM injections — will be a viable prevention strategy for the not insignificant population of immunocompromised people who have suboptimal responses to vaccines. The company has requested Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for this indication — there will be many patients eager for this treatment!

Another study demonstrates that casirivimab and imdevimab improves outcomes for hospitalized patients. We’ve known about the survival benefit of this treatment for seronegative patients from the RECOVERY trial for several months. Here a similar finding of benefit — a reduction in mortality — was found for the seronegative patients, with no signal of harm in those who were seropositive. This treatment (better known as REGEN-COV) is now limited in the United States to outpatients at high risk for COVID-19 disease progression, or for post-exposure prophylaxis. The results of these two studies suggest that modification of the current EUA to allow inpatient use, at least for seronegative patients, cannot come soon enough!

Remdesivir for 3 days given to outpatients with COVID-19 significantly reduced the risk of hospitalization. Only 2/279 of those receiving remdesivir required hospitalization, vs. 15/283 receiving placebo, an 87% reduction; there were no deaths in either arm. No effect was observed on nasopharyngeal viral load, raising the question — are we measuring the right surrogate? While giving remdesivir for 3 days to an outpatient to someone with active COVID-19 would be no picnic, these results are in many ways the strongest efficacy data we have for the drug — and underscore that if giving remdesivir to hospitalized patients, it should be started early (inclusion criteria required symptoms for a week or less). The same likely applies to any antiviral agent.

Am sure there are plenty of studies that I missed, but these in particular caught my eye. And for now at least, in-person meetings have started to return, with many (all) also having a remote option — so-called hybrid meetings. Denver will host a hybrid CROI in February 2022, and we just had a hybrid EACS in London, where my friend Joel Gallant attended.

Here’s his front-line experience:

I’m attending the hybrid EACS in London in person, my first face-to-face conference since the pandemic began. It’s strange to be sitting in a large, largely empty conference room watching a bunch of speakers give pre-recorded virtual talks on a big screen. In many cases there’s no one on stage at all. It’s as though the Zoom meeting has been turned into a spectator sport. But at least it’s easier to get a table for lunch than at most conferences.

Don’t you love pandemic silver linings?

Hey, in case you have some leftover pumpkins after Halloween, here’s something you can do with them.

October 12th, 2021

A Few Thoughts on “Attending” Virtual Meetings

Ouistiti (marmoset), from Buffon and de Sève’s Quadrupeds (1754). Apparently the French say “ouistiti” instead of “cheese” before a photo — perhaps somebody who’s actually from France can confirm or refute.

Once upon a time, long, long ago, before SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19, many of us in academic medicine attended in-person scientific meetings that took place annually around the world.

I was one such person — usually 2-3 times a year. My primary charge at each of these meetings was to assemble the best, or most interesting, or most controversial clinical science and summarize it. Usually, I did this the weekend after the meeting, writing it shortly after walking my dog Louie on Sunday.

He was a very helpful editor.

I called them Really Rapid Reviews©, posted them here, and sent a stern letter to the US copyright and patent offices saying that under no circumstance could anyone copy them and sell them for profit. My crack legal team would be all over violators with the full force of the law.

While that last part (the copyright-patent-legal part) might not be true, the rest of the above narrative is 100% verifiable in these archives.

But then COVID-19 happened. Virtual meetings replaced the in-person scientific ones. I was so overwhelmed after Virtual CROI 2020 — through no fault of the conference, hey it was March 2020 — that I barely remember any of the content, though I did manage to cover one very important study.

Fast-forward roughly 18 months to now. Yes, many of us still “attend” (note the quotes) these virtual meetings — which means for most of us that you go to work as usual and try to snatch some free time to watch pre-recorded presentations on things that sound interesting.

Or you don’t. “Many sessions are like articles I’ve put aside and never get around to reading,” says Dr. Neil Clancy, offering up a perfect analogy. The problem? “Virtual really doesn’t help me disengage from clinic or other duties,” says Dr. Woc-Colburn. Exactly.

If this isn’t enough of a struggle — and believe me, it is — each meeting’s website has a different format, fraught with perilous glitches, sign-in pages that forget who you are, distracting “rooms” and “avatars”, and search function dead-ends. Don’t they know by now that the search function is the #1 key feature in all of these virtual meetings?

Plus, what about the non-meeting activity that happens at meetings? Says Dr. Neil Stone, “Nothing quite replaces the interpersonal connections made at conferences. The conversations you have over a drink at the end of the day are often far more important than sitting listening to the talks, the content of which you often know of in advance.” Indeed this is true!

Grrrr. You can tell I’m not a huge fan of the virtual format — it’s wearing me out.

But for the sake of argument, let me take the side of the virtual meeting proponents.

- There’s that COVID-19 thing — yep, still here, and putting crowds together doesn’t sound like the safest activity. Remember the Biogen Leadership Conference?

- For people with little flexibility in their work or family responsibilities, in-person meetings are out of the question — hence virtual meetings offer the opportunity for a much broader group to attend. No need for the quotation marks around the word attend this time.

- Regardless of your work or home duties, in-person meetings cost a lot, take a ton of time, and are absolute beasts from a carbon footprint standpoint. Let’s not feed that beast!

These are all legitimate points.

Which is why my hope for a post-pandemic world — whatever that means — is that we’ll have the option of both. That’s what’s planned for CROI 2022, and expecting the same from many others.

Looks like you agree:

Let's assume some scientific meetings in 2022 are hybrid — in-person or virtual. Which will you be choosing for those you used to attend? Why?

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 11, 2021

Oh, and since someone asked, the Really Rapid Review© of two recent meetings are all but written. No, they’re not so rapid anymore, but who’s keeping track these days.

October 1st, 2021

A Thank You to One of Our Best Patient-Teachers

Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital lost one of their best teachers this week.

Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital lost one of their best teachers this week.

No, it wasn’t a distinguished professor or astute clinician.

It was one of my long-term patients, who had given himself selflessly to teach dozens of medical students, residents, and (especially) ID fellows over the nearly 30 years I’d known him. Let’s call him Tony. Boy, are we going to miss him.

He worked in a fancy haircutting salon in Boston, where he was highly popular. We first met in the hospital room of his longtime boyfriend in the early 1990s, a grim time for HIV disease. His partner was dying of aggressive lymphoma; I was consulted on the case because of persistent fevers, but there was little we could do.

When our brilliant and perceptive social worker realized that Tony — clearly a kind and friendly man — would soon be alone, she reached out to him.

“How are you doing?” she asked.

“Not so well,” Tony said. “My test is positive too. And I hate my doctor.”

Yes, that could have been a red flag for a difficult patient. But it turns out Tony’s doctor really wasn’t a good match — he was highly judgmental about the fact that Tony had HIV. “He spends more time telling me not to spread it to others than he does trying to help me. I can’t stand the guy.”

So I became his doctor. Over the next few years, Tony’s CD4 cell count fell, he suffered several HIV-related complications, and required admission to the hospital a few times — but through it all he remained cheerful and unfailingly nice. When able, he continued to work full time at the salon, sometimes walking over to the Ritz-Carlton to blow dry a fancy person’s hair before an important event.

“It’s important to them!” he’d say, proud of being in demand. “Plus the money is great.”

Tony had a humble background — he was born in another country, raised in a “rat-infested” (his words) apartment by immigrant parents who didn’t speak English, and he never attended college.

No matter. He got along with everyone — not just the fancy ladies (it was mostly ladies) at the Ritz, but also our aforementioned social worker, our front-desk staff, our nurses, and most notably, our ID fellows.

Over the next 29 years, he must have seen at least a dozen different fellows as they went through their fellowships. He treated each one of them like his primary ID/HIV doctor, never once acting as if they (as trainees) were just “pretend doctors” waiting for the “real” doctor (me) to show up. You can’t imagine how important and empowering that attitude is for doctors in training.

Plus, he agreed to speak at Harvard Medical School classes several times a year, sharing his stories about what it means to live with HIV in the United States. In these sessions, he generously offered his unedited views on American medicine, never sparing certain doctors he’d met with lousy bedside manner.

“He treated me like I was his next down payment on his Cape house,” he said about one particularly aggressive surgeon. “Cha-ching!”

Nope, he wasn’t shy. But what great teachable moments for these young doctors-in-training.

Why do some patients embrace this role in our teaching hospitals? What is it about their personality, and makeup, that gives them the generosity of spirit to help train clinicians? And conversely, why do some people go to a teaching hospital and resent, ignore, or avoid the students, residents, and fellows, treating them as an inconvenience? Don’t they know what the word “teaching” in “teaching hospital” means?

Although I don’t know the answer to these questions, I can assure you that we physicians are exceedingly grateful to the former group for their taking on this very important role — something I told Tony repeatedly over the many years I knew him.

One of the privileges of being an HIV specialist all this time, of course, is witnessing the transformation of this previously fatal disease into one that’s treatable. Tony faithfully took combination antiretroviral therapy as soon as it became available in 1996, and it saved him from dying of HIV. His virus has been under control since then.

Not dying of HIV means that regular diseases of aging start to take their toll, and these did not spare Tony, in particular because he was a lifelong smoker — severe osteoporosis, arthritis, COPD — and innumerable aches and pains plagued him. When he started to lose weight earlier this year (he was already rail thin) a workup quickly established he had pancreatic cancer. “It’s the cancer that gives cancer a bad name,” one Dana-Farber doctor memorably told me.

It was only a couple of months from his diagnosis to his death this past week. He was surrounded by his family, friends, and most importantly, his current partner.

When I mentioned just how grateful I was for all the generous teaching Tony had done over the years, his partner shared that he drank his morning coffee each day always from the same mug.

“It’s a Harvard Medical School mug,” he said. “Has to be that mug.”

Makes sense.

And not bad for a guy who never went to college.

September 22nd, 2021

What I’ve Been Busy Doing, Besides Seeing Patients — and Bonus Animal-Related Infection Podcast

A 1914 postcard from New Zealand, where dogs have amazing abilities.

Long-time readers of this site (and I thank you deeply for that) might have noticed a lengthier gap than usual between today’s post and the previously published one.

Nearly three weeks! Wow! What on Earth is he doing? He must be really busy. That or just lazy.

In order to reassure you that the former is a better explanation for the silence than the latter, here are a few non-patient care things gobbling up the time that typically would go into crafting one of these posts:

1. ID fellowship interviews. COVID-19 notwithstanding, we continue to attract some truly brilliant, mission-driven, and just wonderful young physicians to this field. And can you blame them? It’s by far the most interesting and challenging medical subspecialty, arguably now more than ever.

But the process of reviewing applications, doing the interviews, and submitting our reports takes time — as it should. By the way, check out this paper that surveyed applicants and program directors after the first year of “virtual” recruitment to ID. Seems like virtual here to stay, at least in some capacity.

Just wondering — how many of those interviewees only put on the top half of their interview suits, and stuck with jeans, sweats, scrubs, or shorts for the bottom half? Zoom can’t tell!

2. The NEJM FAQs on COVID-19 vaccines. Or should I write Covid-19 vaccines? For reasons only the editors understand and are keeping secret from me, here on NEJM Journal Watch we write it as COVID-19, while in NEJM itself, it’s Covid-19. Go figure.

But if you know of another content area with greater changes day by day — sometimes hour by hour — than these amazing vaccines, it would be news to me. These FAQs require constant attention and updating, and even then one feels hopelessly behind. Talk about a Sisyphean task, one that might not get easier for some time.

Note that I am both very proud (and surprised) that I spelled “Sisyphean” correctly without looking it up and very grateful to Amy Herman at NEJM Group for her help on this giant project.

3. An opinion piece on the strange lack of guidance for booster doses with the one-shot J&J vaccine. Is the one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine less effective than the mRNA vaccines? Yes. Do we have evidence that giving an mRNA vaccine to prior adenovirus vaccine recipients boosts responses? Yes. Doesn’t even J&J think that its vaccine needs more than one dose?

Probably yes — their opinion further amplified by their press release of some of the ENSEMBLE2 data, though my co-author on the New York Times piece, Dr. Michael Lin from Stanford, still has some concerns:

https://twitter.com/michaelzlin/status/1440373910311034893?s=20

We’ll see. Regardless, it’s just so strange that with all the chatter about boosting the Pfizer-BioNTech (especially) and Moderna vaccines, the 14 million Americans who got one shot of J&J still wait for guidance. “Soon,” say many experts. Will be glad when that day comes.

4. Debating the top animal-related infections, with Dr. Jeanne Marrazzo. She’s the Chief of ID at the University of Alabama, a long-time friend and ID colleague, a scintillating conversationalist, and a true animal lover. One of my junior colleagues considers her a “hero” in ID. Who could be better for this O-F-I-D podcast? Note that I didn’t specify what I meant by “Top Animal Infection” — could be very serious, or having a cool life cycle, or just an amazing name, or having a great clinical anecdote, or some combination of all of the above.

So listen, learn, and laugh! And let me know in the comments if we left out one of your favorite animal-related infections. There are just so many.

(Quick aside — I got the idea for these silly drafts from one of my favorite writers in the world, Joe Posnanski. I even wrote him a fan letter! He does even sillier drafts with comedy writer Michael Schur on his “Poscast”, and gave me permission to do these Infectious Diseases ones since they don’t have overlapping content. He’s about to release a massive book, The Baseball 100. If you have even the slightest interest in baseball, I can’t recommend it strongly enough.)

(Transcript here, and also available on iTunes, Spotify, Overcast, or anywhere you get your podcasts.)

September 3rd, 2021

No, COVID-19 in Anti-Vaxxers Does Not Make Me Happy

Octopus Car Wash, Minneapolis, Minnesota; 1981. John Margolies’ Photographs of Roadside America (public domain).

High-profile people who deny the seriousness of COVID-19, or strongly oppose vaccination, also contract — and sometimes succumb — to the disease.

Surprise, surprise.

The list is long, but recently has included a group of well known conservative radio hosts. Broadcaster Marc Bernier from Daytona Beach, Florida, died of COVID-19 recently.

Bernier called himself “Mr. Anti-Vax”, so it follows logically that he was not shy about expressing his opinions. His last statement on social media compared government advice that people get vaccinated to Nazism.

He was dead less than a month later.

This week, Joe Rogan, a famous podcaster who explicitly discouraged vaccination among young healthy people, announced that he has the disease.

Unlike Bernier, Joe Rogan is recovering (at least as of his last communication). For treatment of COVID-19, he “threw the kitchen sink at it.”

While we might think that someone who refuses vaccination would take the same “natural” approach to therapy — allowing the body’s healing processes to save him without exogenous help — think again. He received monoclonal antibodies (a good move), ivermectin (shrugs), azithromycin (doesn’t work), prednisone (can make mild COVID-19 worse), an “NAD drip” (huh?) and a “vitamin drip” (available now pretty much everywhere).

Best V.I.P. treatment that money can buy! But for the record, our taxpayer dollars are paying for the one thing that probably helped, the monoclonals.

What I find fascinating about these cases of COVID-19 in disease-deniers and anti-vaxxers is our response — as a society in general and as ID doctors in particular.

If one reads the comments on line or on social media, here are some of the common attitudes:

- Anger. They got what they deserve.

- Glee. Schadenfreude in its purest form.

- What a waste. It’s unfair they take up limited resources for treatment.

- Natural selection. It’s Darwinian evolution playing out.

- A weary sadness. I just … can’t anymore.

It’s this last one — sadness — which overwhelmingly dominates ID doctors’ response. Some examples:

Deep sadness and ‘If only’– for them, their families and countless followers and their families …Sadness. Also validation. Followed by sadness about the validation … I will admit to feeling a sense of karma, but mostly it is just more and more sadness … Sad and powerless … Very depressed. It makes the weight of the last 18+ months heavier and heavier and it’s difficult to know how much more we can carry …When I think of their sphere of influence and their many unvaccinated followers’ deaths, which aren’t reported, it makes me incredibly sad …

At its most extreme, it’s a numb feeling, as highlighted here:

My emotional response is I can’t afford to have an emotional response. I just keep going. #IDTwitter. https://t.co/J9TSR3sf4T

— Jo Hofmann (@JoHofmann2) August 29, 2021

So don’t ask us if we’re glad to hear about another anti-vaxxer getting COVID. We’re not glad.

We’re very, very sad — and tired, too.

August 12th, 2021

Could This Be Our First Effective, Inexpensive, Widely Available Outpatient Treatment for COVID-19?

The Geometric Landscapes of Lorenz Stoer (1567)

It’s fluvoxamine.

This rarely used antidepressant, long off-patent, has quietly been going through high-quality clinical studies for treatment of COVID-19. It certainly won’t be endorsed or promoted by any deep-pocketed pharmaceutical company, but deserves some attention nonetheless.

Here’s why I think we might finally be onto something with this “repurposed” drug, even after stumbling numerous times with hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir-ritonavir, ivermectin, azithromycin, doxycycline, colchicine, et al.

First, there is a legitimate mechanism of action — actually, multiple mechanisms, as it has anti-inflammatory, anti-platelet, and potentially antiviral activity independent of its psychoactive properties. If you want to get into the weeds, read this nice summary. But of course many drugs have in vitro mechanisms of action that don’t pan out.

Next, Dr. Eric Lenze and colleagues published a small double-blind clinical trial — well-designed and conducted — which showed benefit. Out of 152 participants enrolled, clinical deterioration occurred in 0 patients treated with fluvoxamine vs. 6 (8.3%) patients treated with placebo, a difference that was statistically significant.

But the problem with such small studies is that a tiny shift in outcomes for the treatment group would substantially change the conclusion. In other words, the results were “fragile.” The authors appropriately concluded that further larger studies were necessary.

After this trial, there was an observational study of opt-in versus opt-out fluvoxamine among newly infected workers at a horse racing track. Despite having more symptoms at baseline, the opt-in group receiving fluvoxamine had better outcomes than those who declined treatment — specifically, 0/65 hospitalizations for fluvoxamine, vs. 6/48 who chose observation only.

But the observational nature of this study also couldn’t provide a high enough level of evidence to change practice. What if the people choosing fluvoxamine were just more “health seeking” — and hence healthier — than those who declined, biasing the result? A highly plausible explanation for the results.

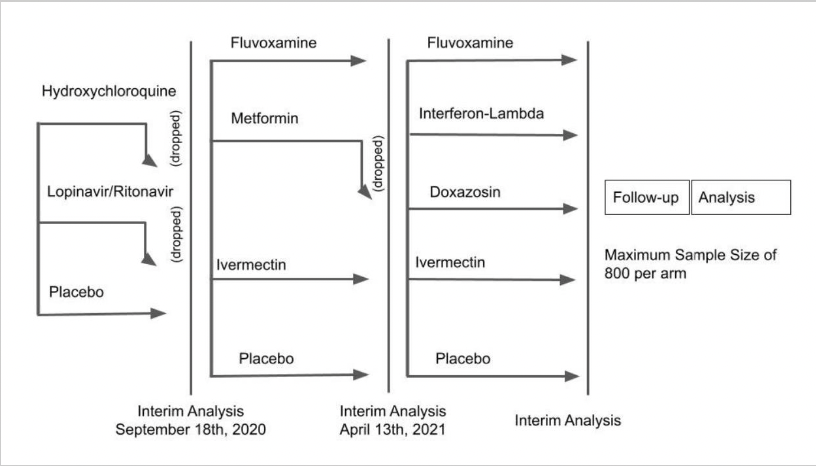

Still, these studies got enough attention to warrant further research, and even a spot on 60 Minutes. The research includes the innovative TOGETHER trial, led by a multinational group of investigators primarily in Canada and Brazil.

Here’s the “adaptive” study design, which shows the tested candidate drugs and the novel way the investigators drop unsuccessful treatments:

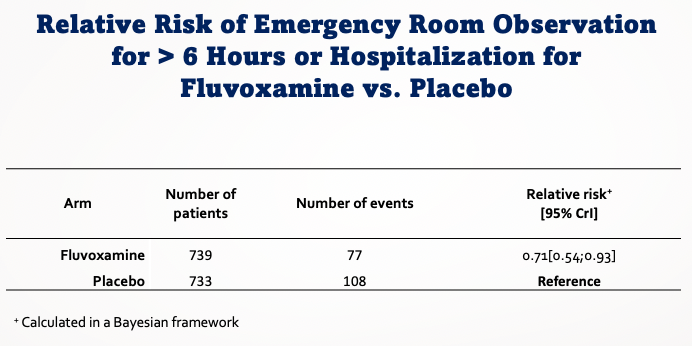

Eligible participants must have had symptom onset within the previous 7 days, a positive test for SARS-CoV-2, be older than 18, and have at least one risk factor for disease progression. The primary endpoint for these outpatient treatments was a composite of emergency room visits or hospitalizations due to the progression of COVID-19. The participants enrolled in 10 study sites in Brazil.

The group already published the negative results of their first study, showing that neither lopinavir-ritonavir nor hydroxychloroquine prevented progression to hospitalization or death better than placebo — which means those treatments have been appropriately dropped.

Time to move on to the next bracket, which included fluvoxamine, metformin, and ivermectin! Interim results were presented for the first time last week at an NIH meeting. The metformin didn’t do much of anything, and has been dropped; the ivermectin did a bit more, but still nothing practice-changing or statistically significant, with a relative risk of progression of 0.91 (95% confidence interval 0.69-1.19).

But the fluvoxamine treatment was much more promising. Among the 1480 participants randomized, fluvoxamine reduced the risk of disease progression by 29% (thanks to the lead investigator Dr. Edward Mills for this updated slide):

Most of the secondary endpoints also favored fluvoxamine, though the differences were not always statistically significant given the smaller event rate. No data on safety were presented, but Dr. Mills verbally stated that there were no unexpected toxicities.

No, an interim analysis of an ongoing study is not enough to change treatment guidelines — but it’s getting close, especially given the lack of other options and the favorable safety profile. The results are strong enough for the investigators to stop this comparison in this study, and no doubt a pre-print and submitted paper should be coming soon for further review.

Look, we’ve all been burned by promising studies of these repurposed drugs, and it’s quite reasonable to reserve final judgment until we see the complete data, and even other studies. Both the University of Minnesota COVID-OUT study and the NIH’s ACTIV-6 study include fluvoxamine arms.

But this already feels different from hydroxychloroquine and company given the high quality of the research. And it raises many interesting questions, including:

- Would the results be additive to monoclonal antibodies, which we know work well in early disease but remain limited in availability, expensive, and cumbersome to administer?

- How about combined with inhaled budesonide? Or with molnupiravir? (As an ID specialist with a research focus on HIV, you can tell I think combination therapy is a very good thing.)

- Should it be tried in inpatients, especially for those requiring oxygen, for whom anti-inflammatory approaches seem most beneficial?

- Would it work in other countries?

- On a global level, would fluoxetine be just as effective, as this SSRI is far more widely available?

- What should clinicians do now? Should they prescribe fluvoxamine for newly diagnosed patients with COVID-19? If so, for which ones?

No, I don’t have the answers. But this looks like progress, which during a pandemic is always great to see.

August 2nd, 2021

Provincetown July Celebration a Challenging Stress Test for the COVID-19 Vaccines

When the complete history of the COVID-19 pandemic is eventually written — and boy oh boy, can’t wait for that — certain events will feature prominently as sites of notable outbreaks.

The Diamond Princess cruise ship

The Biogen Leadership conference

The Skagit Valley Chorale practice

The Amy Coney Barrett White House reception

And now:

The Provincetown Independence Week celebration

So what sets the last one apart from the others? And why did it lead to a change in CDC guidance about masking indoors for vaccinated people?

The answer to question #1 is, of course, that the other events occurred before we had effective vaccines and the highly transmissible Delta variant.

But what about question #2? Why the reversal on masking indoors for people who have been vaccinated?

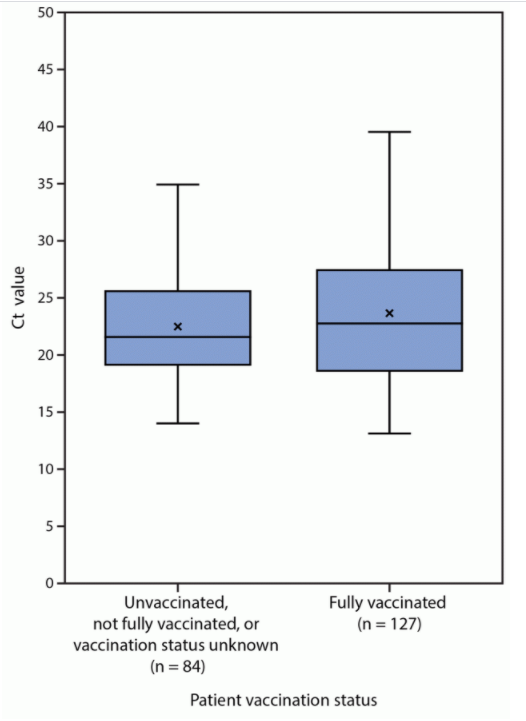

In addition to the sheer number of cases that occurred in vaccinated people, here’s the primary reason, in graphic form from MMWR:

The vertical axis is the cycle threshold value, a measure of how much virus is in the sample (lower is more virus). And as is plainly evident, these results are similar for vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

These suggest that vaccinated people with COVID-19 could spread the virus to others as easily as unvaccinated people. It’s not proof, as it discounts the immune response, which may dampen contagious virus and shorten the duration of viral shedding.

It’s also in contrast with other studies that do show lower viral burdens over time in people who have been vaccinated — including this highly relevant recent study from Singapore:

A recent study out of Singapore shows not only does vaccination prevent you from getting sick with Delta (B.1.617.2), but it is associated with faster decline in viral RNA load. What does this mean? Vaccines make you LESS infectious!

— Chise (@sailorrooscout) July 31, 2021

Regardless, it underscores the plain fact that anyone with symptoms consistent with COVID-19 needs to isolate until recovery, vaccination status notwithstanding. For those diagnosed, we may even need to institute different isolation protocols, since the higher viral loads seen with Delta could mean more transmissions further out from onset of symptoms.

Already, the CDC has recommended that vaccinated people exposed to COVID-19 should get tested afterward, a return to pre-vaccine guidance. Should we also recommend antigen testing in breakthrough cases before return to work? (PCR may continue to detect non-viable viral fragments long beyond the contagious phase.)

What the outbreak can’t tell us is how bad this would have been without vaccines at all. Yes, there were lots of cases, but so far relatively few hospitalizations, and no deaths. Yikes, the mind boggles.

Because if anyone is under the impression that Provincetown is the kind of sleepy Cape Cod small town made famous through Edward Hopper’s dreamy artwork, think again — this July celebration is the diametric opposite. All who attended reported plenty of crowded bars, restaurants, and dance parties, with many shared accommodations among travelers.

You could hardly imagine a better environment for SARS-CoV-2 transmission. These settings plus the Delta variant provided the ultimate stress test for the vaccines.

What the outbreak also can’t tell us is how commonly asymptomatic people who are vaccinated acquire SARS-CoV-2 and then transmit it onward. This question has been filling up the email inboxes of every ID specialist out there.

I suspect it’s uncommon. But let’s not be overconfident about anything related to this tricky virus, which has bedeviled us with unpredictable twists and turns from the start. Humility!

This is quite the figure, from a @CDCgov presentation.

Further evidence of the critical role of humility when it comes to predicting what's next in this pandemic, a lesson we all need to learn again and again.

H/T @washingtonpost https://t.co/1LnqGojF3V pic.twitter.com/IlymSsJOOX

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) July 30, 2021

Yes, that’s a scary figure. What to do in the meantime as Delta is surging?

Get as many eligible people vaccinated as possible. Remember, the vaccines reduce transmission risk in two ways:

- Decreasing the probability of infection in the first place, either symptomatic or asymptomatic

- Decreasing the duration of infectiousness for those who do get infected

That first effect is ironclad — no virus, no transmission. The second one is a bonus. The evidence is strong that both of these are in play with COVID-19 vaccines, as summarized in this superb review.

So approve the vaccines already, FDA! This will allow broader implementation of vaccine mandates in schools and workplaces.

Plus, when possible, we should limit socializing indoors to gatherings with other vaccinated people. Since not everyone can be vaccinated — kids under 12, for example — if you’re planning a large indoor event, go ahead and ask people to get tested ahead of time. We might ask even if everyone is vaccinated, especially if the event has immunocompromised guests. Good tests are widely available over the counter that can give results back in 15 minutes. Let’s use them!

And whatever is causing COVID-19 case numbers to decline rapidly in the United Kingdom and India, here’s hoping it happens here as well.