An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

February 28th, 2023

Really Rapid Review — CROI 2023, Seattle

“Look up there! It’s Microsoft and Amazon stock!” National Archives, 1962.

In a recent chat I had on a local TV network on this year’s respiratory virus season, the host mentioned that “this year felt very post-pandemic”, prompting me reflexively to knock wood — and I’m not a superstitious person.

But even we ID doctors must acknowledge the dramatic improvement in COVID severity this winter compared to the last two, both of which were severe enough to make the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, or CROI, stick to the virtual-only format. And, of course, historically, CROI was the very first scientific conference to go this route, way back in March 2020, a period about which the less said the better.

(Involuntary shudder.)

But on to this year’s CROI, which was available in-person or virtual, taking place once again in Seattle, a place it’s been several times before. It’s our premiere scientific conference, covering not just HIV, but also sexually transmitted infections (STIs), hepatitis, and now SARS-CoV-2, with many excellent studies on all these scourges.

This week, in this Really Rapid Review™, I’ll cover the non-COVID studies, with take-home messages and sometimes a brief comment. You’ll see the abstract numbers in brackets and links to either the abstract (if available) or to the invaluable NATAP site, which somehow continues to aggregate many of the actual slide presentations and posters in real-time. Bravo for that, and long may it live!

- The prognosis for people with HIV has markedly improved since 2012 [870]. This multi-national, large (n=33,598) cohort study demonstrated a significant drop in risk of death during this period, regardless of cause. The leading cause of death was non-AIDS-related cancers, an observation likely to resonate with all HIV providers. Among HIV factors, CD4 <350 and RNA >200 were the strongest predictors of death.

- After treatment failure with NNRTI + 2NRTIs, DTG plus DRV/r was both noninferior and superior to standard of care [198]. This is the first time a boosted PI plus an INSTI has bested a regimen of recycled NRTIs plus a boosted PI. Given the widespread use of DTG + 2NRTIs as fixed-dose “TLD”, which also performed well in this study, I suspect the DRV/r + DTG strategy will not be used much. FYI, the study is called “D2EFT” for “Dolutegravir and Darunavir Effectiveness in adults Failing first-line Therapy” — you knew that, right?

- Switching stable PWH on BIC/FTC/TAF to long-acting injectable CAB-RPV every 2 months resulted in noninferior virologic suppression at 12 months [191]. 670 PWH were randomized 1:2 to continue versus switch to 2-monthly CAB-RPV. While the results met the criteria for noninferiority, there were 5 people on CAB-RPV (3 with resistance) with viral loads >50 in the injectable group, versus 1 in the BIC/FTC/TAF group (no resistance). Counseling people considering CAB/RPV that this therapy comes with a small (but non-zero) risk of failure with resistance is important. Treatment satisfaction improved with the switch. This is the SOLAR study, for “Switch Onto Long-Acting Regimen” — now that’s a good name!

- Switching from BIC/FTC/TAF to CAB/RPV does not lead to weight loss [146]. Data are from the above clinical trial. Meaning — do not use “maybe they will lose weight” as the motivation for the switch to long-acting injectables. Some people gain weight, some people stay stable, some people lose.

- What influences switches to either BIC/FTC/TAF or DTG/3TC [532]? The former is chosen more for those with low CD4 or risk factors for poor adherence; the latter for renal impairment or obesity. So even though these have similar indications, they are not used identically in clinical practice. (Co-author disclosure.)

- Having a detectable viral load in the year preceding a switch to CAB-RPV is a risk factor for detectable viremia following the switch [516]. This study, from the UCSD clinical program that has adopted CAB-RPV more enthusiastically than any other clinic site I’m aware of, found that 25% of switchers end up having detectable viral loads post switch — I’m sure engendering much anxiety! Importantly, one of the investigators told me that failure with resistance in their clinical cohort occurs at a rate comparable to the clinical trials (approximately 1-2%).

- PWH with uncontrolled viremia achieved high rates of virologic suppression on CAB-RPV [518]. More from the UCSF Ward 86 cohort, using CAB/RPV in a non-FDA-approved strategy. Out of 133 PWH who were very much not the usual candidates for this treatment, 57 had viremia. Suppression was achieved in 55 — astoundingly good — with only 2 developing treatment failure. A corresponding modeling study [517] showed this strategy would greatly prolong survival, even with conservative estimates about efficacy (co-author disclosure). We need this success with IM CAB/RPV in people with viremia replicated elsewhere! If it is, I suspect it could enter treatment guidelines, of course with all kinds of caveats and cautionary language.

- Lenacapavir plus two long-acting broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) given every 6 months maintained virologic suppression for 26 weeks [193]. Out of 20 participants, 1 rebounded — unclear why. A study entry requirement was pre-treatment resistance testing showing susceptibility to the bNAbs — a big hurdle if this form of treatment is ever going to be practically deployed. Another hurdle — saying the names of the bNAbs. From an always amusing friend:

- Islatravir (ISL) causes a dose-related drop in lymphocytes that resolves over several months [192]. Welcome back, islatravir! The suspected mechanism of this drop is intracellular accumulation of ISL-triphosphate, leading to apoptosis — not mitochondrial toxicity. The dose moving forward will be 0.25 mg daily, which should be active against wild-type and M184V-containing viruses; the weekly dose (when combined with lenacapavir) will be 2 mg. These data preceded presentations on two phase 3 switch studies of doravirine/islatravir (DOR/ISL) in stably suppressed PWH.

- Stable PWH on any regimen maintained virologic suppression comparable to their baseline treatment when switching to daily DOR/ISL [196]. There were no treatment failures on DOR/ISL versus 3 in the continued baseline regimen in this open-label study.

- Stable PWH on BIC/FTC/TAF maintained virologic suppression when switching to daily DOR/ISL [197]. This was a blinded study and encouragingly showed no difference in treatment-related side effects except for a drop in lymphocytes. (0.75 mg daily of ISL used.) There was a question from the audience about weight changes, which were not presented, but are in the public domain — no significant changes at 48 weeks after the switch. For the record, I have it on good authority that we’re not supposed to call this regimen “door-isil”.

- The weight trajectory of over 20,000 PWH in Kenya switching to dolutegravir differed by baseline regimen [617]. People switching off efavirenz had a sharp increase in weight, one not observed with baseline nevirapine — a reminder that weight effects within drug classes are not uniform, as only efavirenz (among the NNRTIs) appears to have this weight-suppressive effect.

- Weight decreases when TAF/FTC + DTG is switched to “TLD” and increases when the switch is from TDF/FTC/EFV [671]. These changes are exactly as one would predict, as the “T” stands for TDF — which has been shown in multiple studies to suppress weight, in particular when combined with EFV. The mechanism remains unclear. Linked the published clinical study from CID.

- An in vitro model showed that dolutegravir, but not doravirine or efavirenz, disrupted estrogen-mediated fat differentiation [147]. Is this the explanation for the greater weight gain on INSTIs for women than men? By the way, the full title of the presentation was A LOSS OF ERα ATTENUATES DTG-MEDIATED DISRUPTION OF THERMOGENESIS IN BROWN ADIPOCYTES, in case you were wondering. (Abstract not available.)

- Could alteration in GI microflora explain the weight differences between regimens [248]? Gut microbiota among 27 PWH switching treatment from TDF/FTC/EFV to BIC/FTC/TAF showed increased diversity (generally a sign of health), but also increased sC163 (an inflammatory marker associated with obesity) — cause versus effect? There were no controls in this study.

- When controlling for baseline risk factors, integrase-inhibitor-based regimens were not associated with elevated cardiovascular risk [149]. This is reassuring data from the Swiss HIV Cohort study, contrasting with published data from a different cohort. I confess I held my breath when reading the title of the presentation, as this class of drugs is now critical to HIV treatment worldwide.

- Multivariable analysis of a clinical trial comparing BIC/FTC/TAF and DTG+F/TDF showed that TAF looks better for HBV [116]. Predictors of HBV suppression were HBeAg-, HBV DNA <8 log, ALT >ULN and treatment w BIC/FTC/TAF. Longer follow-up of this study, presented originally at the AIDS 2022 meeting, will be important as the TDF-based regimen may eventually catch up.

- Doxycycline given as post-exposure prophylaxis after sex reduced the incidence of syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea in MSM [119]. In a second randomization, the meningococcal B vaccine reduced the incidence of gonorrhea. Called the DOXYVAC study, this was one of several key presentations on the doxycycline preventive strategy during the conference.

- An analysis of bacterial resistance from the Doxy-PEP study found no increase in resistance to GC, Staph aureus, or commensal Neisseria species with PEP [120]. Reassuring data! One caveat is that resistance could happen eventually if this strategy were widely adopted. As a reminder, Doxy-PEP also found that bacterial STIs declined in MSM and trans women who took PEP, as did the original ANRS study (albeit not for GC). That makes 3 favorable studies for doxy-PEP and STI prevention in MSM.

- In women at high risk in Kenya, doxycycline PEP did not reduce bacterial STIs [121]. It’s uncertain why this intervention was not effective in cisgender women — adherence was good, and a separate PK study [118] implied that it should have worked.

- A modeling study applying favorable data on doxycycline PEP to MSM and trans women found that adopting this strategy for those with prior STIs would avert a substantial number of future infections [122]. Not surprisingly, a robust discussion ensued at this session about whether guidelines should recommend doxycycline PEP for certain populations. Though I’m not on guidelines committees for STIs, I’d vote yes — with ongoing surveillance studies for assessment of resistance. Although we use doxy-PEP for tick bites for Lyme areas, this intervention for STIs is likely to be much more frequent.

- Mpox in PWH who have advanced HIV-related immunosuppression can be a severe, disfiguring, and life-threatening opportunistic infection [173]. Mortality was 27% (!) in those with CD4 <100, and the clinical course suggests an IRIS-like phenomenon when ART is started. There is a graphic (and unsettling) display of the Mpox lesions in the published paper. These cases underscore how critical it is for PWH to get on HIV therapy before the disease progresses and also to get at-risk people vaccinated.

- A study of over 6000 women receiving TDF/FTC for PrEP found that the adherence correlates with protection were similar to what’s observed in men [516]. Effectiveness increased steeply with 4 or more pills/week. Previous studies suggested that women required higher levels of adherence than men.

- HIV acquired while receiving PrEP with cabotegravir may be clinically silent and difficult to diagnose [149]. The investigators described delayed detection, negative antigen/antibody tests, and a paucity of symptoms. They even gave this syndrome a name — LEVI, for “Long-acting Early Viral Inhibition” syndrome. Not bad. The key is to use HIV RNA for diagnosis, but these are still going to be very challenging. Here’s a real-life case, occurring in clinical practice.

Had an amazing time at #CROI2023! We were able to share our real world case of breakthrough HIV-1 infection in the setting of on-time, appropriately monitored CAB-LA for PrEP @howardbrownhc.

We greatly appreciated the insightful discussions which I’ll try to summarize below. pic.twitter.com/iLI7WtJSMj

— Anu Hazra (@AnuHazraMD) February 22, 2023

- A complex TB treatment strategy of 8 weeks (!) of bedaquiline + linezolid added to INH, PZA, and ethambutol was noninferior to the standard 6 months of therapy [113]. The study, called TRUNCATE-TB, was just published in the New England Journal of Medicine. But before getting too excited, there are caveats about implementing this challenging approach — lots of them! There is a good summary of these concerns in the accompanying editorial and in this thread.

Of course, there were numerous additional interesting studies not mentioned here, apologies if I left out your favorites — feel free to cite them in the comments.

And it was really fun to visit Seattle again, a place with a strong familial connection. Plus, the sparkling new wing of the convention center hosted the conference.

The weather? Cold and rainy — winter in Seattle, you know — and it even snowed a bit the last day. No one ever accused the CROI organizers of picking their winter locations in tropical paradise, that’s for sure.

February 14th, 2023

Interferon Lambda for COVID-19 — Looking Good, but Still Not Available

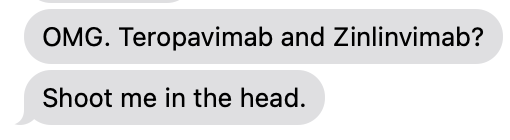

Way back in the spring of 2022, I was asked to give an update on outpatient treatment of COVID to a group of general internists. The talk featured this slide on the TOGETHER trial of peginterferon lambda:

These data came from a press release from the company developing the drug. It’s dated March 17, 2022.

I added the highlight over the last bullet to make fun of my very bad prediction. Oops. Clinicians who treat COVID, or have known people treated for COVID (which covers essentially 100% of the U.S. adult population at this point), realize we still don’t have interferon lambda as a treatment option, now nearly a year later.

I summarized the reasons for my initial optimism in an opinion piece for the Boston Globe written with Dr. David Boulware (clinical trialist extraordinaire), namely:

- Efficacy shown even in vaccinated people

- Worked across all variants

- Dropped viral loads faster

- Side effects comparable to placebo

- “One and done” treatment

- No drug interactions

- Might work against other viral infections too!

Yep, the TOGETHER trial interferon results — published this past week in the New England Journal of Medicine — look really solid.

It’s not a perfect clinical trial. There were some issues with the drug supply during the study, and the blinding, and some have criticized the primary endpoint. There were apparently enough concerns that the FDA did not agree to meet with the company to discuss an Emergency Use Authorization. But all studies have weaknesses. I don’t think these are sufficient to invalidate the results.

Plus, it’s worth remembering that our current COVID treatments are hardly flawless. None of our treatments has documented efficacy in vaccinated high-risk outpatients. Other issues:

- Molnupiravir may not be effective at all — and has legitimate safety concerns.

- Paxlovid has a boatload of drug interactions and that annoying rebound syndrome that we still don’t know how best to predict or manage. Grrrr. (That’s annoyance.)

- Three days of intravenous remdesivir is cumbersome to set up, requiring either a visit to an infusion center or dedicated home care services, and hence is out of reach for many.

- Omicron and its subsequent mutations made all the previously available monoclonals inactive. So if you spent many hours learning how to spell (or pronounce) bamlanivimab, casirivimab, imdevimab, etesevimab, sotrovimab, tixagevimab, cilgavimab, or bebtelovimab, consider that a sunk cost.

I’ll acknowledge that reduced disease severity lowers the urgency of introducing a new therapy for COVID. Nevertheless, hundreds of people a day are still dying, and this virus isn’t going away anytime soon. Here’s a not-so-bold prediction — we’ll see a surge of cases pretty much every late fall and winter for the foreseeable future.

And having interferon available for COVID would greatly facilitate studying its use in other viral respiratory tract infections. Its mechanism of action, augmenting the host immune response to viral infections, could show activity across a broad spectrum of such pathogens — influenza (including H5N1) and RSV most notably, but even other common viral pests (metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, the pre-SARS-CoV-2 coronaviruses). I contacted the TOGETHER study’s senior author, Dr. Jeffrey Glenn, who wrote:

I have been advocating for a trial I call the RELIEF (REspiratory viruses treated with Lambda IntErFeron) study, where patients who present with acute respiratory symptoms are immediately randomized to lambda or placebo, and we sort out later what virus they have. This could generate more data in COVID, but importantly advance the ball further by generating new data for other viruses of pandemic potential. We could leverage the same great infrastructure of the TOGETHER trial and hopefully generate game-changing data.

So, here’s hoping this promising and novel therapy gets another chance, perhaps in this confirmatory study.

Oh, and by the way, my Globe piece prompted this email from my daughter Mimi:

Go dad!! Great title.

Yep, it’s one of my better ones.

February 6th, 2023

New Ways with Language — Some to Adopt, Some to Question

Mary Cassatt, Young Mother, 1888. US Postal Service stamp, 2003.

Back in my second year of medical school, my classmate and good friend John and I had a memorable teacher in our Introduction to Clinical Medicine course, someone we still talk about today. A general internist with a specialty in addiction, he was a big bear of a guy sporting a ponytail, beard, open-necked shirts (sometimes of the Hawaiian variety) and beads.

You know those stereotypes of Boston academic physicians with bow ties and tweeds? The opposite of that.

One of his emphatic messages was to stop labeling people by their diseases. “He’s not an alcoholic,” he’d say, after we’d done an awkward medical student history and physical at a local inpatient detox center. “He’s a person with alcoholism. That’s the disease he has, not the person he is.”

It wasn’t just for people with addictions. He said the same was true for people with diabetes, or asthma, or anything. They’re people, not their diseases.

At the time — the mid 1980s — this was not at all a commonly held view in medicine. Our other teachers, and certainly the residents we looked up to, bandied about disease-first labels all the time. Alcoholic, IVDA (intravenous drug addict), chronic lunger, end-stage AIDS victim, schizophrenic, sickler, and on and on.

Even worse, these labels could come with a room or bed number. “Shooter in 4 needs two sets of blood cultures.” Cringe.

Fast-forward to today, and I’m delighted to say that our teacher was onto something important by not wanting to label people with their disease. The language we once used seems not only unnecessary, but stigmatizing.

In an effort to move away from such labels, Dr. Sara Bares has written a wonderful viewpoint in Clinical Infectious Diseases on this very topic. She kindly invited me and others to collaborate, but she did the bulk of the very fine writing. I highly recommend it.

In fact, my main contribution was to acknowledge that change can be hard — and harder for those of us accustomed to language done a certain way. For this particular effort, however, I’m convinced the challenge is worth it. Clinicians and researchers should do whatever we can to avoid using stigmatizing language for our patients with their diseases, whatever they might be.

I confess to having the opposite reaction to certain other requested changes in language, especially those that seem driven more by fashion or, even worse, virtue signaling. Such requested changes, while well meaning, come off as peculiar; at best, they’re even unintentionally funny (in the “ha ha” definition). For example, the first time the term “chestfeeding” crossed my path (over the more anatomically correct “breastfeeding”), I thought it was a joke.

What is accomplished by this awkward change, or even more important, what is lost? Isn’t that what mammals do as one of their core nurturing traits? Use their breasts to feed their young? And shouldn’t we be encouraging and facilitating breastfeeding (over formula or expressed milk feeding) whenever possible as optimal for infant health? Cripes, the origin of the word mammals is even named after this function.

At worst, extreme mandated changes in language come across as dogmatic and performative, serving only to criticize, alienate and anger people who won’t adopt them. They are fodder for political opponents, using examples to show how out of touch the other party might be.

In the same week that Sara published her paper on people-first language, Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times wrote about the effect of different and more extreme language changes. He cites, of course “chestfeeding,” and includes a whole panoply of other bewildering terms for consideration.

His concern?

While this new terminology is meant to be inclusive, it bewilders and alienates millions of Americans. It creates an in-group of educated elites fluent in terms like BIPOC and A.A.P.I. and a larger out-group of baffled and offended voters, expanding the gulf between well-educated liberals and the 62 percent of Americans 25 or older who lack a bachelor’s degree — which is why Republicans like Ron DeSantis have seized upon all things woke.

It’s no wonder that one of my colleagues — who could not be more humanistic and thoughtful in both her clinical practice and actions — told me that in an upcoming seminar she’s leading on fighting racism in the hospital, her biggest fear is “when, not if, I mess up the latest terminology.”

Language evolves. It’s time to welcome non-stigmatizing language in medicine and research, but that doesn’t mean all medical terminology needs to flip to the latest fashion. In other words, Dr. Beads-with-Ponytail was 100% right not calling people by their diseases — but I doubt he’d ever say “chestfeeding.”

January 17th, 2023

After the PANORAMIC Study — Whither Molnupiravir?

Photo by Piret Ilver on Unsplash.

We turn now to the second of the controversial papers published in late 2022 on COVID-19 — namely the PANORAMIC study of molnupiravir versus usual care in outpatients with the disease. This one is controversial not because the study was poorly done, or unimportant, but because molnupiravir has, from the start, been a contentious treatment for this disease.

Conducted in the United Kingdom, PANORAMIC was impressively large, enrolling over 25,000 people. Eligible participants had symptoms for 5 days or fewer, and were either older than 50 or had comorbidities known to increase the severity of the disease. Randomization was to open-label molnupiravir or usual care. The primary endpoint was hospitalization or death. Importantly, 94% of the participants had already received three doses of a COVID-19 vaccine.

The main study results were negative — hospitalization or death occurred in only 1% of participants in both groups. Serious adverse events were evenly matched between arms.

On the plus side, people assigned to receive molnupiravir had a substantially faster time to recovery, 9 vs. 15 days, which yielded a >99% chance of the molnupiravir being superior to usual care for this protocol-specified endpoint. Active treatment also decreased healthcare utilization, and reduced viral load compared to usual care.

The critical view of molnupiravir: Great study in a highly relevant population — those who are not just “fully vaccinated,” but also boosted. In this context, molnupiravir did nothing to reduce the serious outcomes of hospitalization or death.

And ignore those time to recovery results. It’s an open-label study, with people getting active treatment of course thinking that what they’re getting is working. The placebo effect in treatment trials can be massive.

Only this isn’t a harmless placebo — it’s an antiviral with a concerning mechanism of action, inhibiting viral replication by increasing the frequency of viral RNA mutations. Such a process could conceivably spawn more contagious or more immune evasive SARS-CoV-2 variants, something we definitely want to avoid.

Plus, there’s the ongoing concern about mutagenesis, which has implications for those of reproductive age, and might have other long-term safety issues.

Finally, molnupiravir isn’t cheap. Don’t be fooled that it’s “free”, or covered by insurance, or government programs. It’s $700 for a five-day course, another disadvantage it has compared to placebo.

Now that we know this giant, well-done study is negative, can we take molnupiravir off the treatment guidelines completely, please? Or consider withdrawing the Emergency Use Authorization?

For further concise, and (mostly) critical thoughts, read the responses to this post:

— Patrick Kenney (@PatrickKenney7) January 13, 2023

The supportive view of molnupiravir: Great study — helps put this treatment in the current-world context of COVID being milder in people who are vaccinated or who have immunity from prior disease, or both.

And though molnupiravir made no difference in the primary endpoint (which was reassuringly rare in both arms), that faster time to recovery sounds pretty great. It’s better than we’ve seen in open-label studies of influenza treatment, so it is unlikely just due to the unblinded study design.

Given the option of recovering from a nasty respiratory tract infection in 2 weeks with no treatment, versus less than 10 days with molnupiravir — and no major side effects — I’ll take the latter, thank you.

And dropping viral load might reduce household transmission, and speed time to being able to get back to work and other activities. Both big wins.

Plus, let’s look at molnupiravir in the context of other treatment options:

- Nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir has many drug interactions, so can’t be given to some of our patients at highest risk for severe COVID.

- Remdesivir in the outpatient setting sounds great, but anyone who’s tried to set up 3 consecutive days of intravenous treatment for patients in the ambulatory setting know this is a tall order, indeed.

- The monoclonal antibodies are toast.

Molnupiravir clearly has a role.

My take on molnupiravir: We need to acknowledge that the clinical data on this drug are mixed — at best. In the blinded phase 3 study, MOVe-OUT, the patients receiving treatment who had pre-existing immunity to SARS-CoV-2 did not benefit at all — in fact, the placebo group did better. And the study on hospitalized patients, MOVe-IN, was also negative.

Also, there are legitimate concerns about its mechanism of action, both related to variant generation and mutagenicity.

In short, there are excellent reasons why the preferred treatments for non-hospitalized high-risk adults in the NIH Treatment Guidelines are not molnupiravir, but nirmatrelvir boosted with ritonavir or intravenous remdesivir. A footnote reads, “Molnupiravir appears to have lower efficacy than the other options.”

But as I wrote previously when the data from PANORAMIC were first released, this improvement in time to recovery does stand out, and it is plausible that secondary transmission would be reduced. So I don’t think that molnupiravir is useless — especially given the limitations of our other treatment options.

So back to the guidelines, which state molnupiravir should be used in high-risk outpatients with COVID “…when the preferred therapies are not available, feasible to use, or clinically appropriate.”

Perfect, and it’s exactly what I’ve been doing.

Meanwhile, can we get some further data on other treatment options that are easier or safer to use? I’m thinking in particular the unboosted protease inhibitors ensitrelvir* and EDP-235, interferon lambda — and maybe even cheap (and very safe) metformin.

(*A very wise ID PharmD has kindly informed me that the drug interactions with this protease inhibitor are likely to be just as complex as with nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir. Oh well.)

January 4th, 2023

Medical Masks vs. N95 Respirators for Preventing COVID-19 Among Healthcare Workers

As promised, the end of 2022 saw a trio of controversial COVID-19–related publications.

As promised, the end of 2022 saw a trio of controversial COVID-19–related publications.

First up is something that always causes a stir — a study on masks! Reviewing a study on masks in the COVID-19 era is like poking a hornet’s nest with a stick, and this one is no exception.

But let’s poke away! Aside from receiving a lot of attention when it first appeared online, it gives us a chance to review some interesting clinical research principles.

Here’s the study question — does using a medical mask while caring for a person with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 provide healthcare workers “noninferior” protection to an N95 mask?

That “noninferior” term is often confusing, so best to translate it into plain English, which is what Harvard biostatistician Michael Hughes kindly did for me many years ago. Noninferior simply means “not too much worse than.” Noninferiority studies are great when the thing you’re testing has other advantages to the standard of care — it might be simpler, or cheaper, or both. As a result, a noninferiority design is quite appropriate for comparing surgical masks (cheaper, easier) to N95s.

Now one thing the statisticians ask us clinicians is to define the noninferiority margin — in other words, if not-too-much-worse is a key determinant, how much worse would we tolerate? In this study, if the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval of the hazard ratio of surgical to N95 masks was less than 2, then they’d be declared noninferior.

That sounds like a lot — would we really tolerate something that gives us only half the protection of an N95 mask? One thing to remember about noninferiority margins is that the smaller the margin, the bigger the required sample size. I suspect that anything smaller would have made the study impractically large.

The study was conducted in 29 healthcare facilities in Canada, Israel, Pakistan, and Egypt from May 2020 to March 2022, with 1009 participants. It’s important to scrutinize the dates of all COVID-19 studies because the vaccines, prior COVID-19 (with residual immunity), and variants have greatly changed the nature of SARS-CoV-2’s transmissibility, severity, and our response to it. As I’ve noted previously, the post-Omicron era includes vastly more people who had COVID, and vastly more people who stopped preventive measures while out and about in society.

So finally, let’s get to the primary results. RT-PCR–confirmed COVID-19 occurred in 52 of 497 (10.46%) participants in the medical mask group versus 47 of 507 (9.27%) in the N95 respirator group. You don’t have to be a statistician to conclude that these numbers are pretty darn close.

This yields a hazard ratio of 1.14, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.77 to 1.69. That means the surgical masks could be as much as 69% worse (but less than twofold worse, the non-inferiority margin), or even 23% better, at protecting healthcare workers.

In short (drumroll), the strategy of wearing surgical masks was noninferior to N95s among people caring for people with confirmed or suspected COVID-19.

Perspectives on this study:

The critical view: The study was sloppy and, frankly, unethical. It’s already been proven in several models that filtration of respiratory viruses is more effective with a well-fitted N95 than regular masks — and COVID-19 is clearly transmitted by an airborne respiratory virus.

A twofold noninferiority margin is way too high. Even if they’re only 69% worse, why should healthcare workers take the chance?

The study didn’t even test the efficacy of the masks, since undoubtedly many of the participants got COVID while not even caring for COVID-19 patients and not wearing the N95s — either elsewhere in the hospital or (even more likely) in the community. This is especially true in Egypt, which accounted for many of the cases in the study during the post-Omicron period. How can we say the masks didn’t work when infections were occurring outside the patient room?

Let’s look at another country, how about Canada? There, surgical masks were more than twofold worse than N95s. Shouldn’t that be our model?

Finally, the study took a long time to enroll and had several modifications before completion. Doesn’t that alone make the results unreliable?

The supportive view: This study proves that a policy of recommending uncomfortable, expensive N95 over surgical masks is pointless. The highest form of evidence — the randomized clinical trial — shows they’re noninferior to cheap surgical ones.

Lots of clinicians hate N95s. When the study was first posted online, one of the smartest doctors I know asked me flat out — “So can I finally ditch these things? By the end of the day, I feel like my face has been in a vice.”

Yes, there are differences between countries, but importantly this was a post-hoc analysis. We should ignore these analyses because if you measure something frequently enough with smaller and smaller sample sizes, you’re bound to find something that’s statistically significant that supports your hypothesis.

And if you’re going to focus on a country, isn’t the current landscape of COVID much more like Egypt (during Omicron and high community transmission) than Canada (early in the study, very low event rates)?

As for those filtration studies? Remember, clinical trials enroll human beings — not mannequins or robots wearing masks.

My take: Both sides have excellent points. I learned a lot from reading insightful commentaries taking both sides of this debate — both praising the study (here and here) and criticizing it. Plus, there’s an excellent accompanying editorial.

As for what I think?

I believe that if the study were large enough, if the N95 masks were properly worn and correctly fit tested, if in-hospital COVID-19 transmission in break rooms during snacks and lunch could be excluded, and (an even bigger task) if transmission at restaurants and weddings and concerts and gyms (meaning in the community) could be excluded, then this study would have shown that surgical masks are not as good as N95 masks in protecting healthcare workers.

In other words, they’d be too much worse to make up for the lower cost and greater comfort. More than twofold worse, as defined by the study.

But that’s a lot of ifs, and is not the real world. The real world is messy, and such stipulations would be impossible. In the real world, the surgical masks in this randomized clinical trial were noninferior for the primary endpoint of PCR-diagnosed COVID-19 in the healthcare workers.

Using N95 masks in the post-Omicron era is like giving someone an excellent umbrella during a rainstorm, but only during the brief downpours when dashing from the car to the front door — the times of highest direct exposure. The rest of the day, with steady and frequent rain, they use either a broken umbrella or none at all. Plenty of chances to get wet.

No wonder the study showed surgical masks to be noninferior. COVID-19 is now everywhere, and patient-to-healthcare provider transmission of the virus is a small fraction of the exposures happening globally.

Do I still wear an N95 when caring for patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19? Yes. After all, I still use an umbrella when dashing from the car to the door during a downpour.

Do I also believe that getting COVID-19 is much more likely at a restaurant or party or medical meeting than in the patient’s room?

Also yes. That’s just the world we live in now.

December 27th, 2022

Finishing the Year with Some ID Things We Can All Agree On

Don’t be fooled by the cute face. Right behind those whiskers are razor sharp teeth teeming with Pasteurella multocida.

There are some things in ID for which there is universal agreement among our infection-obsessed clan. You might not believe it based on the squabbles over pandemic-related issues in the press or social media, but it’s true!

Here’s a quick 10 off the top of my head, and of course there are more:

- Childhood immunizations are good.

- Treating the common cold with antibiotics is bad.

- HIV treatment saves lives.

- Staph aureus bacteremia can have life-threatening complications.

- Cat bites are nasty, can transmit Pasteurella multocida.

- People start losing their protective immunity against malaria when they move to a non-endemic region.

- Eating oysters may be hazardous to your health (but we might eat them anyway).

- Most people who say they’re allergic to penicillin really aren’t.

- Drug interactions with rifampin are a big pain in the ___.

- Azithromycin is a good drug, but not for the things it’s used for most commonly.

Gather 100 knowledgeable ID docs in a room, and votes should be unanimous in agreement on these views.

I suppose there could be a contrarian finding their way into the group, who somehow thinks that Staph bacteremia is no big deal, that rifampin plays well with other drugs, and that oysters are sterile, but that person would be thought of (appropriately) as very strange (and very wrong). You won’t see debates at IDWeek, our big national meeting, in which people take the opposing viewpoints on these 10 things, unless Bizarro World or Opposite George has an IDWeek.

Why do I bring these ID universalities up? Because the end of the year yielded three COVID-19–related papers that stirred up quite the debates from people in our field.

What’s so striking is that many of the people taking the opposite views are smart, knowledgeable, and well-respected in ID. All of them are well-meaning, hoping for the best path forward for managing this still-new viral infection to humankind. Yet, their opinions on these studies could not be more diametrically opposed.

In the next three posts, to kick off the new year, I’ll quickly summarize the papers, along with some of the divergent views. And I’ll briefly give you my take which, true to my personality (so I’ve been told, even teased about), seeks some middle ground — because in all three there are valid arguments on both sides. Hey, it’s worth a try, right?

Take it away, George!

Happy New Year, everyone!

December 19th, 2022

Chaos in the Diagnosis of Pneumocystis Pneumonia

Confession — no one knows the best way to diagnose Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, commonly abbreviated as PJP, or for some stubborn old timers, PCP.

Don’t believe me? Take a look at this poll — not just the results, but the extraordinary diversity of responses — then head on back here for a historical perspective sure to excite ID, pulmonary, oncology, transplant, and rheumatology geeks the world over.

Hey ID clinicians of #IDtwitter, what are you using for first-line Pneumocystis jirovecii diagnosis on respiratory samples in your center/hospital? Would be helpful to hear why. Thanks!

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) December 5, 2022

So how did we get to this confusing state of affairs?

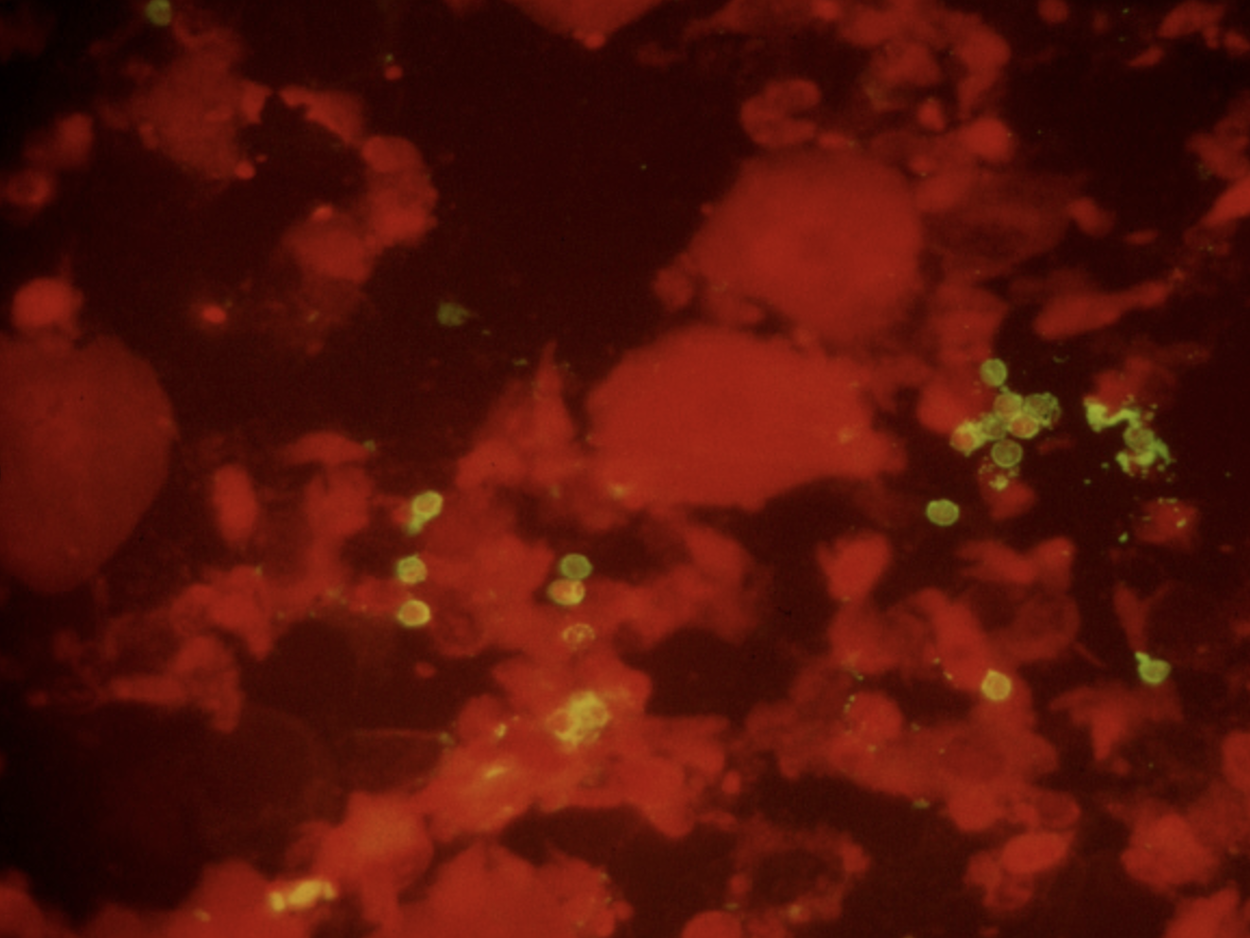

For many years during my early ID career, diagnosis of PJP was by microscopy only — literally seeing the organisms under a microscope. You couldn’t culture this tricky fungus in standard labs, so you needed to examine sputum, or fluid from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), or in really tough cases, tissue from a lung biopsy. The sensitivity of microscopy, especially on induced sputum — respiratory secretions obtained by having the patient breathe nebulized hypertonic saline — varied widely depending on the quality of the sample and the skill of the person doing the microscopic exam.

Immunofluorescence staining of sputum, positive for P. jirovecii cysts (green).

Back in the early 1990s, we were lucky to have a highly skilled microbiologist named Walter working in our hospital lab. Among his many talents was his uncanny ability to spot the characteristic “apple green” cysts of Pneumocystis jirovecii on immunofluorescence stains of induced sputum samples, sparing patients more invasive procedures (bronchoscopy or lung biopsy). That’s a picture he sent me years ago for teaching purposes, in case you’re wondering. During an 18-month period roughly from 1992-4, Walter made this diagnosis over 100 times, almost all of them from induced sputum specimens obtained from people with HIV — it was before we had effective HIV therapy.

Fast-forward a decade or so, to the mid-2000s, when I had the opportunity to visit the Cleveland Clinic for an educational event. The trip included a tour of the microbiology laboratory, the capabilities of which absolutely floored me. Wow, what an impressive place! First, the lab was GIGANTIC. Second, it did all sorts of cutting-edge diagnostics that we could only dream about in our hospital lab. One of these tests they did was pneumocystis PCR on respiratory secretions or BAL fluid, with the head of the lab, Dr. Gary Procop, telling me it all but replaced immunofluorescence staining at their center.

He also told me PCR was much more sensitive in the patient population that increasingly made up the majority of cases of PJP — non-HIV immunocompromised hosts. PJP incidence in PWH had dropped dramatically with effective ART, and one was much more likely to see a case of PJP in a transplant recipient, or in someone being treated for cancer or an autoimmune condition.

The problem with PCR? Some people with positive tests arguably had colonization only, not disease, hence it required clinical judgment to interpret the results correctly. This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as a “false positive”, but more accurately it’s the “true, true, but unrelated” situation. They have pneumonia (true), they’re PCR positive (true), but something else is causing it.

Meanwhile, another test entered the picture at around the same time, blood beta-glucan. Beta-glucan is a component of the cell wall of many fungi, including Pneumocystis — hence people with PJP often have positive beta-glucan tests.

Note that I didn’t even mention it in the above poll, because it’s very different from microscopy and PCR. How different?

- It’s a blood test. It’s much easier to obtain than respiratory secretions.

- It’s quantified. Some “positive” tests are much more positive than others.

- It’s non-specific. A bunch of other fungi, including candida and histoplasmosis, also trigger a positive test — as does a boatload of non-infectious things, including surgical gauze, intravenous immune globulin, hemodialysis, certain medications, owning a pet rabbit (made that up), who knows what else.

It’s this lack of specificity that makes beta-glucan results such a head-scratcher for clinicians. On ID consult services around the country, many will recognize (and groan) at the “we sent a beta-glucan, it’s positive, and we don’t know what to do with it” consult. It rivals the “5 days post-cardiac surgery, has leukocytosis, unclear cause” consult in frequency.

But the convenience of beta-glucan makes it irresistible, and we adopted it with great enthusiasm at our hospital — so much so that the residents began referring to getting a “g and g” on many admissions, shorthand for “glucan and galactomannan.” Plus, under the right circumstances, it obviated the need for an induced sputum or a bronchoscopy. Specifically, in a classic case of HIV-related PJP, a beta-glucan > 500 had a very high predictive value positive for the diagnosis. Unless you’re practicing in histoplasmosis-endemic regions, usually no further testing is needed.

So where does that leave us? How can a practicing ID clinician make their way forward with these three diagnostic tests battling it out?

Faced with a microbiology lab overwhelmed with COVID-19 and a shortage of technicians, we’ve stopped doing microscopy for PJP (Walter has retired, alas), and instead, just offer PCR. It’s a send-out test that takes a few days to come back. (I was surprised that some of the respondents to my above poll said it took over a week! It’s not like they need to get the genetic sequence of the bug.) Blood beta-glucan is still available as well.

So here are my observations so far, with the caveat that I work in a region with a relatively small population of untreated people with HIV (we have amazing ART access in Boston) and a very large population of non-HIV immunocompromised hosts.

- PCR is more sensitive than microscopy. Gary Procop was right.

- The incidental positive PCR test isn’t such a big deal. As noted, we have a lot of immunocompromised people here. We tend to believe the positive tests mean something. Gary was right about this, too.

- Beta-glucan is still sometimes useful — but only when sent with a reasonable pre-test probability of PJP. Otherwise, you’ll be dealing with a ton of perplexing positive results.

Especially if the patient owns a pet rabbit.

Can’t get enough on this topic? Here’s a terrific review of all things pneumocystis, by a couple of local experts.

November 29th, 2022

#IDTwitter — Still a Wonderful and Entertaining Place to Learn

Twitter is much in the news recently, mostly for not-good reasons. Rather than rehash-tag (see what I did there?) its various struggles and controversies since the new owner took over, I’m going to let others cover that territory.

Twitter is much in the news recently, mostly for not-good reasons. Rather than rehash-tag (see what I did there?) its various struggles and controversies since the new owner took over, I’m going to let others cover that territory.

Instead, I’d like to go in a different direction, and share how this site remains one of the most valuable tools for learning about ID — and other medical and not-so-medical news.

It’s also a ton of fun. That is, if you’re careful, and know the rules, which I’ll get to in a moment.

First, here’s brief summary of how I figured out Twitter. I’m hopeful by sharing that you’ll consider joining. Plus, the more smart, engaged, and nice people we have on Twitter — people actively communicating about our fascinating field — the better it becomes.

It began for me in 2009, shortly after the tech writer David Pogue wrote about Twitter in the New York Times. He described a chaotic mess with essentially no rules — a place where you could crowdsource solutions to complex problems, or “entertain” people by sharing what you cooked for breakfast, or market your latest business idea, or link a piece of writing you found particularly profound, or show a puppy video that makes you gasp at the cuteness.

Or, all of the above.

But the best part of his piece was this comment:

DON’T KNOCK IT TILL YOU’VE TRIED IT. Of course, this advice goes for anything in life. But listen: even my own masterful prose can’t capture what you’ll feel when you try Twitter. So try it. If you don’t get any value from it, close the window and never come back; that’s fine.

As a big Pogue fan, and with nothing to lose, I thought — why not? So I signed up. Then, after trying it for 10 minutes or so, and remaining utterly baffled, I then just ignored it completely — for the next 6 years.

What changed?

Several things, happening all around the same time. First, I noticed that both some of my younger colleagues — and especially the medical residents and ID fellows — could cite recently published or presented research I hadn’t yet heard. Where’d they get this cutting-edge information? They all said one place: Twitter.

Here’s a recent example of a clinical trial published in JAMA that totally would have been off my radar screen for quite a while without Twitter, posted by the invaluable account @ABsteward:

https://twitter.com/ABsteward/status/1577318206993092610?s=20&t=avV7L4-RD1LpzYW9A3Yunw

Second, one of my editors here at NEJM Journal Watch, Kristin Kelley, expressed astonishment that I wasn’t promoting my own writing on Twitter. “Every writer does this,” she said, bluntly. Then she gave me a brief tutorial.

Now I do it regularly. Example:

Mask and vaccine mandates? Check. Socializing and networking over meals and drinks? Check. Some thoughts about this uncomfortable paradox here.

Big In-Person Medical Meetings and Cognitive Dissonance for ID Docs https://t.co/TnIz1Kgq2G @PriyaNori— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) October 17, 2022

Third, after dipping my toes in the water, I started seeing the highlights of major scientific conferences on Twitter without having to travel. No time away from home. No airfare. No registration fee. No hotel charges. For example, the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, or ECCMID, is a terrific meeting I’ve “attended” every year via Twitter since 2016.

Believe me — I am well aware that Twitter can be a place of discord and clashes, a site where people say stupid things they later regret, things that literally ruin their careers. Worse, Twitter can be the source of serious bullying and threats. Having been the target of some of these attacks (which most reliably occur after I post something about the benefits of vaccines), I can only imagine what it’s like to be the target of something broader, or even more sinister.

How then, to stay out of trouble? Here I turn repeatedly to Peter Sagal, best known as host of NPR’s eternally funny “news” show, Wait Wait, Don’t Tell Me. Peter’s “Rules of Twitter” are so effective that not only will adherence to them generally keep you from entering into the toxic fray, but you’ll find yourself applying them to real life too, making you a happier person. That’s pretty great.

So here they are in their entirety, conveniently “pinned” to the top of his profile page:

These are my Rules of Twitter, developed over many years via trial and (mostly) error. They are *my* rules, related to what I want to do On Here and what I want to avoid. Yours may and will differ, but I do suggest figuring out what they are. pic.twitter.com/tib7vZ4ORF

— @petersagal.bsky.social (@petersagal) November 8, 2021

For this year’s IDWeek, I was kindly invited to present the good side of #IDTwitter. The session also included two terrific talks by ID colleagues — Dr. Krutika Kappalli, who discussed what it feels like to be the victim of hate speech and abuse triggered by speaking plainly about science and public health, and Dr. Payal Patel, on how to engage news media from across the political spectrum on ID issues.

People who attended IDWeek can see watch the talks, but for others, I’ve gone ahead and posted a condensed version in a Twitter “thread” — check it out! — then come back here and watch this truly hysterical video.

Which I learned about on Twitter by “following” several talented comedians, including this guy.

November 21st, 2022

Five ID Things to Be Grateful For, 2022 Edition

Household magazine, 1952.

In what’s something of a holiday tradition on this site, I hereby present 5 ID things we can be grateful for as we prepare for the best holiday of the year. Why the best?

Family and friends. A nice big meal, with something for everyone. (My family of four has two vegetarians — they have plenty to eat.) No pressure about gifts.

And, most importantly, a chance to express gratitude, something we all should do more often.

I say you can’t beat it, and since this is still my column/blog/whatever (checks over his shoulder), that will be the final decision.

Onto the 5 things, starting with the very most obvious:

1. Trending toward endemicity. No, the pandemic isn’t “over” — especially for people who are immunocompromised, or very medically fragile. And Long Covid remains a persistent challenge and mystery.

But boy has COVID-19 changed.

I speak annually each fall in a Harvard postgraduate course for hospitalists. This is the third year I’ve spoken about management of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients.

The first 2 years, my case-based talk included patients with oxygen-requiring pneumonitis, with discussions about remdesivir, dexamethasone, tocilizumab, baracitinib, and other promising immune-based therapies. Pulmonologists spoke of ventilation strategies and ECMO.

This year? My case for discussion was someone admitted to the hospital with congestive heart failure, “incidentally” found on testing to have COVID-19 — maybe it tipped them over, maybe not. Most of the talk was about outpatient therapies (yes, it’s a hospitalist course — it was a reach), and managing that tricky nirmatrelvir rebound syndrome.

“We might have you pivot back to HIV,” said the course director, inviting me back for next year’s course. That would be just fine!

So while there’s still plenty of COVID-19 out there — and influenza and RSV have come charging back — we appear to be past the stage where our ICUs fill up with COVID-19 pneumonia, forcing our hospitals to restrict their basic functions. Draconian family visitor policies are gone. Some hospitals have even stopped testing all their asymptomatic inpatients.

Fingers crossed it stays this way. After all, it was last year at this time that Omicron hit. I’ve learned, with this virus, not to take anything for granted.

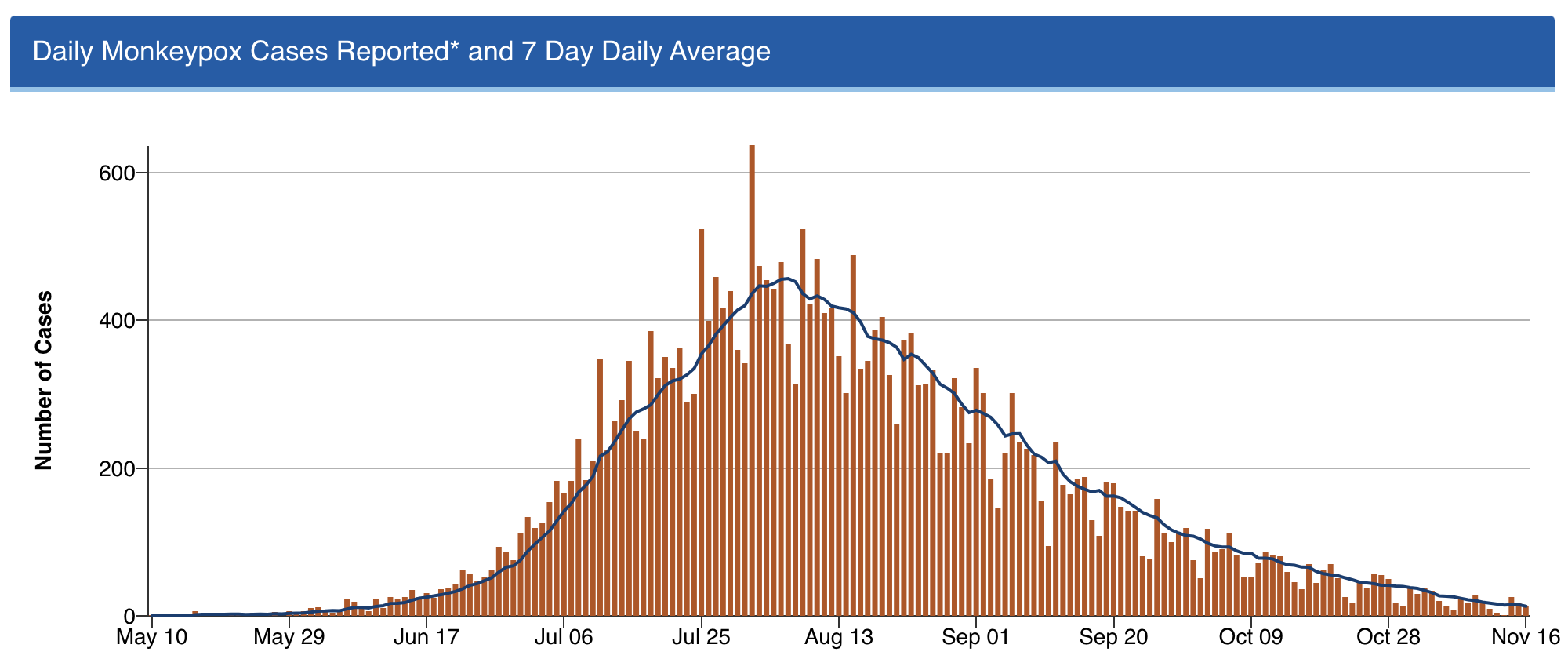

2. Monkeypox is under control. Back in July, one of my colleagues was spending nearly all of her time managing referrals for confirmed and suspected cases of this new (at least to us) sexually transmitted infection.

(And yes, it’s mostly sexually transmitted. I know there are debates about this nomenclature, but that’s for another time.)

It was tough, and her actions were heroic — full PPE for each case. Tecovirimat applications to the CDC. Struggling with Jynneos vaccine shortages. And, worst of all, some cases so severe they required hospitalization.

As the case numbers increased, we had to wonder — when was the steep increase in case numbers going to peak? Anecdotal cases with no apparent exposure, outside of the primary risk group (men who have sex with men), raised the possibility that this scary thing would explode even further.

But thanks to a spectacular collaborative effort by CDC, local public health officials, the gay community, and the roll-out of the Jynneos vaccine, the incidence of this viral infection dropped wonderfully.

Got to love this curve:

Shout out to Dr. Demetre Daskalakis (among others) — but I’ll give him extra credit as he’s a graduate of our ID program. He was quite the special ID fellow, and is quite the special ID doc!

3. Professional meetings are back — but now with a remote option, too. I spoke recently with someone who attended IDWeek this fall in Washington DC, asking her what she thought about the experience.

“It was wonderful,” she said. “I had a great time.”

She smiled as she said this — almost guiltily, I thought.

It’s an opinion I’ve heard repeatedly from those who went. There was something so strange, yet so exhilarating, about attending. Seeing old friends and colleagues for the first time in years. Marveling at the survival of our specialty, brutal though our experience has been. Sharing what it took to get through it.

But not everyone is ready to go back to these meetings — I understand that. The cost, the carbon footprint, the time away from work and from family — all negatives. And let’s be ID nerds about it, there’s no doubt that interacting with others at professional meetings is a risk factor for transmission of viral respiratory tract infections. Always has been, always will be.

Fortunately, the big meetings seem to understand all this, and now offer the chance to attend remotely. For IDWeek, 7431 attended in person, 2160 virtually.

I would call that progress.

4. Dolutegravir — and by extension, bictegravir — hold up stronger than ever. For those readers who don’t do HIV treatment, here’s little secret — it’s never been easier. Dolutegravir- and bictegravir-based treatment, consisting of these drugs plus tenofovir/emtricitabine (or lamivudine), is so sensationally effective that all but the tiniest fraction of people who take this combination achieve virologic suppression.

(I lump dolutegravir and bictegravir together since they’re quite similar — enough so that there’s even a colossal legal agreement about it.)

It’s worth acknowledging up front that these treatments aren’t perfect. We still have that frustrating weight gain issue, and a signal of possible excess cardiovascular risk. A fraction of people get headaches and insomnia from the drugs, and can’t take them. But by and large these treatments just work — and work better than anything we’ve ever had in the 35 years we’ve had antiretroviral therapy.

Treatment-naive and treatment-experienced. Resistance to the NRTIs or no resistance. Viremic or suppressed. Young and old. Advanced HIV disease or asymptomatic.

Sure, there are exceptions. If you push any drug too hard, with suboptimal adherence, or super high viral loads and severe immunosuppression, or drug interactions, you can select for resistance. In the NADIA trial of people failing second-line therapy, dolutegravir plus 2 NRTIs was noninferior to darunavir/ritonavir plus 2 NRTIs, but 9/235 in the dolutegravir strategy developed resistance, versus zero in the darunavir arm. The world is now conducting a massive conversion of most HIV treatment to “TLD” (tenofovir-lamivudine-dolutegravir), and it will be critical to follow this roll-out to explore the incidence of this resistance, the risk factors, and the optimal management.

But so far, in clinical practice, resistance to these second-generation integrase inhibitors is a rare enough thing that most experienced HIV clinicians have at most a handful of such cases in their practice. And we essentially never see it when people with virologic suppression switch.

Oh, and by the way — that concern about dolutegravir exposure during conception and neural tube defects? Gone! Thanks to the primary investigators, who accumulated a ton of more data since the first report in 2018, the incidence is now comparable to that with other ART strategies. Dolutegravir is now a recommended treatment for all pregnancy categories.

That last fact alone is worth some serious gratitude.

5. #IDTwitter — still a wonderful and entertaining place to learn.

Yep, chaos at the top notwithstanding, it still is.

But that’s the topic for my next post … provided the site is still running when I write it!

Hey, if you ignore the #EndOfTwitter stuff, the content on here remains pretty great https://t.co/O73xiLS6ZI

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) November 18, 2022

Happy Thanksgiving, Everyone! What are you grateful for this year?

November 7th, 2022

Five Quick Questions from Our Course, “ID in Primary Care”

Examples of non-digital, non-electronic learning tools, for historical purposes only.

As noted on this site before, we put on a course called “ID in Primary Care” every year for clinicians doing truly the hardest job in medicine — frontline primary care. Why is their work so challenging? While we can focus on one field, infectious diseases, they have to be aware of everything.

Tough task indeed.

We’ve been holding our course virtually since 2020, so this is our third time with the online-only, live-streaming format. On the plus side, this has allowed a greater number of participants, saves a whole lot of money both for travel and the meeting venue, and certainly has a much smaller carbon footprint.

On the other hand, we miss the direct contact with those who attend. Plus, Zoom fatigue is a real thing, and we have zero idea if our jokes land.

Pros and cons of this approach aside, we still draw a great mix of internists, family practitioners, nurses, and PAs, and every year they ask us terrific questions about clinical problems that they encounter on a regular basis.

Here are a quick five:

Question #1: I have a patient who says they get recurrent shingles several times a year, so she’s periodically back on valacyclovir. I can’t find anywhere how to manage this — boost their vaccine? Suppressive valacyclovir? If so, what dose? Help!

Answer: Ah, the patient with “recurrent zoster” — I put it in quotes because most of the time it’s actually not zoster at all. It’s either HSV (which can look strikingly similar) or a dermatologic manifestation of post-herpetic neuralgia, where someone has pruritus or discomfort in the same anatomic location of a zoster outbreak, so they scratch away and develop itchy red bumps.

When patients do get another case of zoster, it’s usually in a different dermatome, separated from the first episode by several years.

Have your patient stop the chronic antivirals if they’re on them, and next time they have an outbreak, get a swab and do a PCR for HSV and VZV on the lesions. If the diagnosis is still uncertain, have them check in with your favorite ID-oriented dermatologist if you’re lucky enough to work with one of these brilliant clinicians.

For more on this entity, read The Patient with “Recurrent Zoster”, which I have sent along to numerous eConsulters over the years.

Question #2: My patient is about to start a TNF blocker for ulcerative colitis. She comes from a country that gives BCG vaccine to all children. Should she get both an IGRA and a tuberculin skin test to rule out latent TB? I worry about false positives with the BCG.

Answer: If your prior probability of latent TB is low, as it is for most U.S. citizens, then one test should suffice, and go with the interferon gamma release assay (IGRA). However, if the person is from a highly TB-endemic region, especially if they recently immigrated here, and are about to start these immunosuppressive medications that greatly amplify the risk of TB reactivation, then the guidelines say to consider doing both — and this is what we would recommend. If either test is positive, I would give preventive therapy before starting the anti-TNF agent.

And no, prior BCG should not dissuade you from this strategy. As some regions where this vaccine is administered have very high rates of TB, there is no way to distinguish positive skin tests from BCG (which fade over time), versus from latent TB, versus both — and the vaccine doesn’t work that well in adults anyway.

For more, check out these terrific online resources:

BCG and false-positive tuberculin skin tests

Question #3: My patient has recurrent UTIs, but she is older with chronic renal disease. What’s the real story on use of nitrofurantoin in this setting?

Answer: Nitrofurantoin has made an amazing comeback in UTI treatment over the years, largely due to rising rates of community resistance to other agents and concerns about fluoroquinolone toxicity. However, it has poor tissue penetration, and prescribing information has long said not to use at CrCl <60 ml/min because of insufficient renal excretion and accumulation of the drug leading to more toxicity — in particular that nasty pulmonary hypersensitivity syndrome.

By contrast, in a 2015 review by the American Geriatrics Society, the conclusion was that nitrofurantoin could be safely used down to an estimated GFR of 30, provided the treatment course was 7 days or shorter.

Helpful to know this if other options are limited.

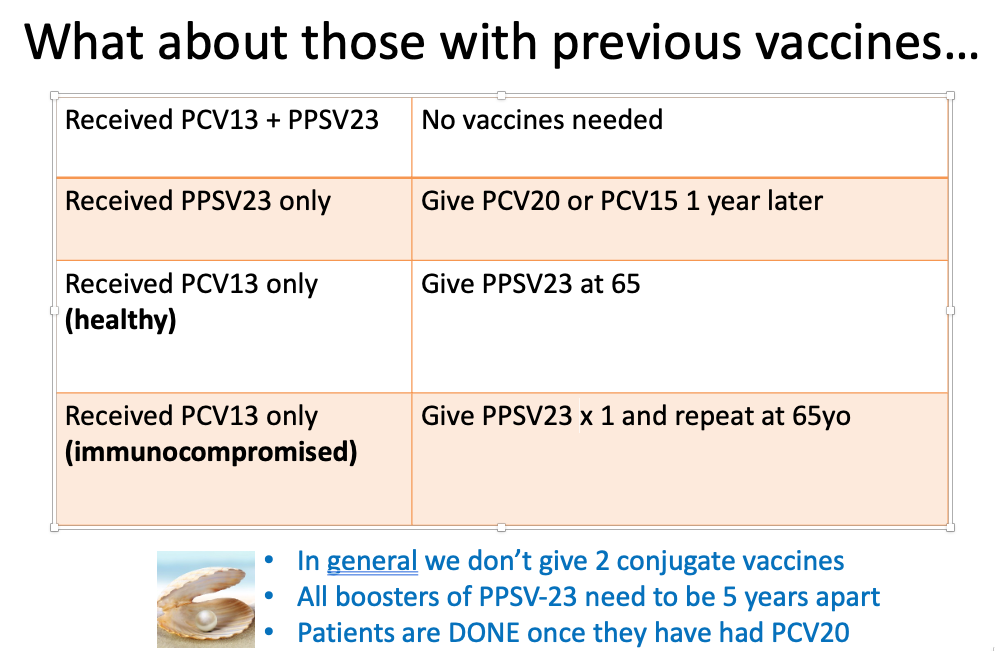

Question #4: I know that the pneumococcal vaccine recommendations have been updated, but it’s so confusing what to do with so many options. Any simple way of addressing this, in particular for those patients who’ve been vaccinated before?

Answer: We’re most definitely in a transition phase when it comes to pneumococcal vaccination, driven by the availability of the two new conjugate vaccines, especially the 20-valent one. Sometime in the near future, everyone getting a pneumococcal vaccine will get the pneumococcal 20-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV-20), and be done. Hooray!

But until then, we have a whole slew of people who’ve received older vaccines, both the conjugate (PCV13) and the polysaccharide versions (PPSV23). What should we do with them now?

My colleague Dr. Mary Montgomery put together this handy slide for her talk on adult immunizations, which I am sharing with her permission:

Question #5: Is the pandemic over?

Well it’s not over — but it sure has changed.

Want evidence? Just imagine this video appearing a year ago — inconceivable.

Today? It was a big hit on SNL this past weekend.

Suspect that for some, it’s too soon, while for others, it’s perfectly timed satire.

For me, it’s both. How about you?