An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

December 19th, 2022

Chaos in the Diagnosis of Pneumocystis Pneumonia

Confession — no one knows the best way to diagnose Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, commonly abbreviated as PJP, or for some stubborn old timers, PCP.

Don’t believe me? Take a look at this poll — not just the results, but the extraordinary diversity of responses — then head on back here for a historical perspective sure to excite ID, pulmonary, oncology, transplant, and rheumatology geeks the world over.

Hey ID clinicians of #IDtwitter, what are you using for first-line Pneumocystis jirovecii diagnosis on respiratory samples in your center/hospital? Would be helpful to hear why. Thanks!

— Paul Sax (@PaulSaxMD) December 5, 2022

So how did we get to this confusing state of affairs?

For many years during my early ID career, diagnosis of PJP was by microscopy only — literally seeing the organisms under a microscope. You couldn’t culture this tricky fungus in standard labs, so you needed to examine sputum, or fluid from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), or in really tough cases, tissue from a lung biopsy. The sensitivity of microscopy, especially on induced sputum — respiratory secretions obtained by having the patient breathe nebulized hypertonic saline — varied widely depending on the quality of the sample and the skill of the person doing the microscopic exam.

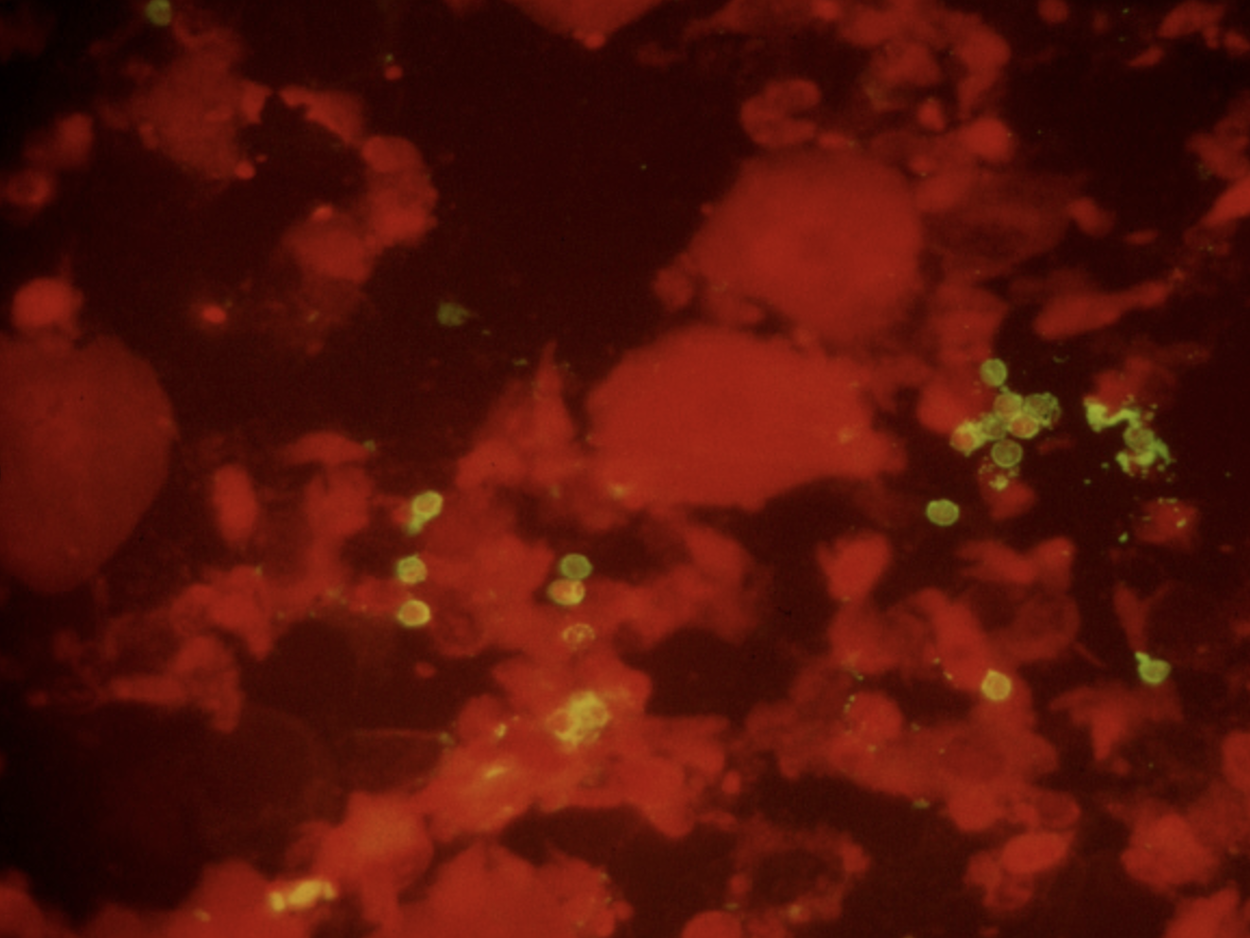

Immunofluorescence staining of sputum, positive for P. jirovecii cysts (green).

Back in the early 1990s, we were lucky to have a highly skilled microbiologist named Walter working in our hospital lab. Among his many talents was his uncanny ability to spot the characteristic “apple green” cysts of Pneumocystis jirovecii on immunofluorescence stains of induced sputum samples, sparing patients more invasive procedures (bronchoscopy or lung biopsy). That’s a picture he sent me years ago for teaching purposes, in case you’re wondering. During an 18-month period roughly from 1992-4, Walter made this diagnosis over 100 times, almost all of them from induced sputum specimens obtained from people with HIV — it was before we had effective HIV therapy.

Fast-forward a decade or so, to the mid-2000s, when I had the opportunity to visit the Cleveland Clinic for an educational event. The trip included a tour of the microbiology laboratory, the capabilities of which absolutely floored me. Wow, what an impressive place! First, the lab was GIGANTIC. Second, it did all sorts of cutting-edge diagnostics that we could only dream about in our hospital lab. One of these tests they did was pneumocystis PCR on respiratory secretions or BAL fluid, with the head of the lab, Dr. Gary Procop, telling me it all but replaced immunofluorescence staining at their center.

He also told me PCR was much more sensitive in the patient population that increasingly made up the majority of cases of PJP — non-HIV immunocompromised hosts. PJP incidence in PWH had dropped dramatically with effective ART, and one was much more likely to see a case of PJP in a transplant recipient, or in someone being treated for cancer or an autoimmune condition.

The problem with PCR? Some people with positive tests arguably had colonization only, not disease, hence it required clinical judgment to interpret the results correctly. This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as a “false positive”, but more accurately it’s the “true, true, but unrelated” situation. They have pneumonia (true), they’re PCR positive (true), but something else is causing it.

Meanwhile, another test entered the picture at around the same time, blood beta-glucan. Beta-glucan is a component of the cell wall of many fungi, including Pneumocystis — hence people with PJP often have positive beta-glucan tests.

Note that I didn’t even mention it in the above poll, because it’s very different from microscopy and PCR. How different?

- It’s a blood test. It’s much easier to obtain than respiratory secretions.

- It’s quantified. Some “positive” tests are much more positive than others.

- It’s non-specific. A bunch of other fungi, including candida and histoplasmosis, also trigger a positive test — as does a boatload of non-infectious things, including surgical gauze, intravenous immune globulin, hemodialysis, certain medications, owning a pet rabbit (made that up), who knows what else.

It’s this lack of specificity that makes beta-glucan results such a head-scratcher for clinicians. On ID consult services around the country, many will recognize (and groan) at the “we sent a beta-glucan, it’s positive, and we don’t know what to do with it” consult. It rivals the “5 days post-cardiac surgery, has leukocytosis, unclear cause” consult in frequency.

But the convenience of beta-glucan makes it irresistible, and we adopted it with great enthusiasm at our hospital — so much so that the residents began referring to getting a “g and g” on many admissions, shorthand for “glucan and galactomannan.” Plus, under the right circumstances, it obviated the need for an induced sputum or a bronchoscopy. Specifically, in a classic case of HIV-related PJP, a beta-glucan > 500 had a very high predictive value positive for the diagnosis. Unless you’re practicing in histoplasmosis-endemic regions, usually no further testing is needed.

So where does that leave us? How can a practicing ID clinician make their way forward with these three diagnostic tests battling it out?

Faced with a microbiology lab overwhelmed with COVID-19 and a shortage of technicians, we’ve stopped doing microscopy for PJP (Walter has retired, alas), and instead, just offer PCR. It’s a send-out test that takes a few days to come back. (I was surprised that some of the respondents to my above poll said it took over a week! It’s not like they need to get the genetic sequence of the bug.) Blood beta-glucan is still available as well.

So here are my observations so far, with the caveat that I work in a region with a relatively small population of untreated people with HIV (we have amazing ART access in Boston) and a very large population of non-HIV immunocompromised hosts.

- PCR is more sensitive than microscopy. Gary Procop was right.

- The incidental positive PCR test isn’t such a big deal. As noted, we have a lot of immunocompromised people here. We tend to believe the positive tests mean something. Gary was right about this, too.

- Beta-glucan is still sometimes useful — but only when sent with a reasonable pre-test probability of PJP. Otherwise, you’ll be dealing with a ton of perplexing positive results.

Especially if the patient owns a pet rabbit.

Can’t get enough on this topic? Here’s a terrific review of all things pneumocystis, by a couple of local experts.

I have seen an inordinate number of false positive PJP PCRs at my institution. It is more common than a true positive. Of course it depends on the patient population and pre-test probability. Thank goodness our path lab still performs GMS stains. Plus what about sending the specimen for DFA? The common reference labs still do these assays I believe.

Interesting! Are these sent in immunocompromised patients with pneumonia? If so, how does one know they’re “false positives”?

Since these PJP PCR assays are send outs, they take ample time to come back. Sometimes 1 week. My ID colleagues and I will get a call to review bronchoscopy results. Occasional a Pneumocystis PCR has been thrown into the 5 to 10 random tests that the pulmonary specialist selected when doing the prior bronchoscopy. I can’t tell you how may times the Pneumocystis is positive. The patient is already better or has no complaints whatsoever by the time we see them. I will admit that most of these patients do not have a super high pre-test probability of “severely” immunocompromised state (e.g. AIDS, blood cancers, etc). I then make sure these same specimens have been reviewed by our pathologist for the classic silver stain. I also wonder whether DFA would be better (we used to do them at UC Irvine where I was a fellow). Thanks!! Alex

Dear Alex,

We have been performing PCP PCR for almost 10 years and while we do not see considerable numbers of false positive results PCP PCR results, we find corroborating positives with serum B-D-Glucan (BDG) a very useful way of confirming true positivity. BDG is approximately 90% sensitive for the diagnosis of PCP in the HIV cohort and approximately 85% sensitive in the non-HIV patient, so in general if the patient is PCP PCR positive and has PCP then they will also be BDG positive and when both are positive there is a high probability of PCP. We also find PCP PCR testing of an upper respiratory tract specimen (dry throat swab) or even blood a highly specific (>95%) way of diagnosing PCP.

Kind regards,

Lewis White

I won’t comment on diagnosis, but as for nomenclature I’m sticking with “PCP.” In the paper that announced the renaming the organism (Stringer JR, et al. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2022;8:891-6), the authors refer to the disease as “PCP” and include this section addressing the disease name issue:

“Acronym “PCP” Retained:

Given the compelling evidence that the human form of Pneumocystis is a separate species, the most important objection to designating it as such has been the problem that this name change could create in the medical literature, where the disease caused by P. jiroveci is widely known as…PCP. This problem can be avoided by taking the species name out of the disease name. Under this system, PCP would refer to Pneumocystis pneumonia. This simple modification in the vernacular accommodates the name change pertaining to the Pneumocystis species that infects humans. Furthermore, adopting this change makes the acronym appropriate for describing the disease in every host species, none of which, except rats, is infected by P. carinii.”

Then again, I AM a “stubborn old-timer”!

As a comparable old-timer, I was holding on to PCP for years, but have finally joined the other side. Too many youngsters now say PJP, never having even heard of PCP.

Haha, I tend to avoid the abbreviation and just refer to Pneumocystis pneumonia not wanting to call it PJP yet. But alas, we have lost that fight as PJP has become the common vernacular amongst the next generation.

Great discussion! Our lab has done IF for years, but I understand from lab medicine colleagues that in addition to decreasing technician experience with identifying cysts, obtaining the control reagent for IF has become more difficult. This may lead our center to switch to PCR, which would be a major change. For other centers using PCR, I wonder how many are using a qualitative assay vs quantitative (or semi-quantitative)? Seems a quantitative assay would help with interpretation. I like the idea of sending BDG in addition to PCR to help confirm the diagnosis.

The level of evidence is still poor for interpretation of quantitative PCR assay. We need more studies to evaluate the utility of quantitative PCR test to differentiate between colonization and the disease. There is a poor association between quantitative level in PCR and severity of PJP in HIV-negative patients; therefore, a low quantitative level cannot be always interpreted as colonization.

I think we have oversimplified the concept of “false positives.” There are analytical or procedural false positives caused by things such as inadvertent dilution of a specimen, cross-contamination in the laboratory, mislabelling, transport/handling errors, contamination due to errors in phlebotomy technique, etc. These are just “wrong” results.

However, I think most false positives are analytically correct but clinically misleading. That is really a different thing from the examples I just mentioned. Positive Pneumocystis PCRs in people without pneumocystosis are a good example. Others include biological false positive RPRs in people with lupus or mononucleosis, or positive Coccidiodes antibodies in patients with histoplasmosis.

There are others that may not fit perfectly neatly into this binary classification (e.g., false-positive IgM serologies), but I think it is a useful concept, especially for teaching.

There is at least one other category, the cerebral false positive, or misinterpretation of a test. Examples might be someone thinking a persistent positive treponemal serology means active syphilis, or that GNR growing in an anaerobic blood culture bottle must be an obligate anaerobe. These types of errors happen a lot.

Analytical, biological, cerebral. Try that on rounds.

What a light hearted, jovial narration of the topic and the equally captivating discussions!! Yes. After all the false positives in newer tests which very many times do not distinguish living from dead, organism from chemicals oozing from gauze, it boils down to ‘seeing is believing’. Gold is gold after all.