An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

February 23rd, 2012

Hepatitis C and the “Retooling” of HIV/ID Specialists

The news that hepatitis C (HCV) has passed HIV as a cause of death in the United States got quite a bit of attention when it was first presented last year at ICAAC — and no doubt the published paper, in this week’s Annals of Internal Medicine, will also cause a stir.

The news that hepatitis C (HCV) has passed HIV as a cause of death in the United States got quite a bit of attention when it was first presented last year at ICAAC — and no doubt the published paper, in this week’s Annals of Internal Medicine, will also cause a stir.

In fact, I boldly predict that going forward, (approximately) 94.2% of HCV-related research grants, journal articles, and lay press articles will cite this paper, making it (for now) the “Palella NEJM 1998” of HCV.

(For those of you who don’t know Palella NEJM 1998, this was the first paper in a major medical journal to demonstrate the dramatic decline in HIV-related mortality due to effective HIV therapy. Figure 1 from that study is permanently emblazoned on HIV specialists’ retinas.)

But the Annals paper also reminded me — again — that there’s a significant retooling going on in the HIV/ID field to accommodate HCV. And for some docs and HIV organizations, it’s more than a retooling — it’s practically a comprehensive overhaul. What do I mean exactly? Some citations, some anecdotes:

- The International AIDS Society – USA is now officially known as the “International Antiviral Society – USA” and has HCV therapy as a major focus of its efforts.

- Two large HIV annual educational meetings — one led by Clinicial Care Options, the other called Opman — both now prominently include hepatitis as a substantial component of their conference agenda. In fact, both have even changed their names: “2012 Annual CCO HIV and Hepatitis C Symposium” and “Optimal Management of HIV Disease & Hepatitis“.

- Several of the larger clinical trials sites for HIV therapy now devote a significant proportion of their research efforts to HCV. The leader of a well-known site told me that nearly half of their studies are now HCV-related.

- Many clinical ID practices (including ours) now openly solicit patients with HCV (not just HIV/HCV co-infection).

Of course, it’s easy to see why this is happening. These HCV cases call for all the skills we’ve sharpened over 16 years of combination antiretroviral therapy — managing complex regimens, myriad side effects, virologic responses, resistance, and drug-drug interactions.

Then there’s the dynamic pace of HCV therapeutic research. Seemingly every week, there’s another major story, most of it happening too quickly for peer-reviewed medical journals. See here for an example.

Oh, and you get to cure people. Wow.

By contrast, HIV therapy is in a plateau phase, with few major recent advances in treatment. The top four recommended initial regimens haven’t changed since 2009, and they are all remarkably effective. Clinical sessions of HIV follow-up have been likened to “well-baby checks”, a startling turnaround from the drama of HIV practice just a few years ago.

Yawn. And I mean that in the best possible way. Patients are doing great!

So if HIV/ID specialists seem to be jumping on the HCV bandwagon, it’s completely understandable. Though whether gastroenterologists mind sharing this bandwagon with us is highly debatable — most would probably just as soon let us drive, given the current difference in compensation between endoscopy and office management of medically and socially complex patients.

Perhaps I should even rename this blog “HIV, HCV, and ID Observations”?

Nah, it still needs a complete name overhaul — and I’m waiting for some good suggestions.

February 14th, 2012

Is It Time To Stop Treating Acute Sinusitis?

From the pages of JAMA comes this startling clinical trial:

A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of adults with uncomplicated, acute rhinosinusitis [who] were recruited from 10 community practices in Missouri between November 1, 2006, and May 1, 2009 … [Subjects received a] ten-day course of either amoxicillin (1500 mg/d) or placebo administered in 3 doses per day … There was no statistically significant difference in reported symptom improvement at day 3 (37% for amoxicillin group vs 34% for control group; p=.67) or at day 10 (78% vs 80%, respectively; p=.71).

To be fair, I did leave out that outcomes favored the amoxicillin group at day 7. And I also left out that the validated instrument they used to gauge symptoms was called the “Sinonasal Outcome Test-16”, or “SNOT-16”

Ahem.

But still — I’m willing to wager good money that if you asked 100 primary care providers, ENT specialists, ID doctors, and patients whether they thought antibiotics helped relieve symptoms of acute sinusitis, 90% would answer “yes.”

And 99% would would want it for themselves.

Critics of this study might quibble about the inclusion criteria, or the fairly large number of screened study subjects who were not enrolled, or the selection of amoxicillin over amoxicillin-clavulanate. What, no Moraxella catarrhalis coverage?

Regardless, this trials reminds us that, even though it’s hard to believe, the human species did survive many eons before the discovery of antibiotics in the 20th century, and that furthermore, most of the common community-acquired infections resolve spontaneously.

Time will tell whether the results from the study will influence practice guidelines, patient perception, and — most importantly — clinical practice.

February 12th, 2012

Impossible Curbside at Medical Grand Rounds

Scene: Medical Grand Rounds, 5 minutes before the start. Lecture is on coronary artery disease, which may have a link to Infectious Disease even if it isn’t actually caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae or CMV after all.

Scene: Medical Grand Rounds, 5 minutes before the start. Lecture is on coronary artery disease, which may have a link to Infectious Disease even if it isn’t actually caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae or CMV after all.

A well-regarded, experienced primary care physician (PCP) approaches.

PCP: Hi Paul, I have quick question*.

[*Curbsiders often use this exact phrase — and rarely does it correlate with whether the question is actually “quick”.]

Me: Sure.

PCP: One of my patients has a urine culture that’s persistently positive for MRSA* — I’ve repeated it twice. Should I treat it?

[*Ah, our old friend MRSA. Odds of this question actually being “quick” have just plummeted.]

Me: Hmm, those results could be a sign of systemic infection, with secondary seeding of the GU tract.*

[*We ID doctors are probably — no, definitely — biased towards badness. Which makes us worriers. After all, why else do we get involved in a case?]

PCP: But he’s completely asymptomatic*. Do I need to treat it?

[*I am pretty sure, by his giving me this information, that he does NOT want to complicate matters by looking more deeply into the matter. But he’s slightly unsure about this approach, so he wants me to endorse his action. Or more accurately, his lack of action.]

Me: Then I bet it’s in his prostate — MRSA can cause prostatic abscess, or chronic prostatitis. You could get a prostatic ultrasound or pelvic CT to investigate further.*

[*At this point, our malpractice lawyers would like me to insert into the conversation defensive boilerplate language, such as, “I’ve given you some general information about a general patient, but I don’t know this case well enough for me to render specific medical advice. At your request or the patient’s request, I would be happy to become involved in evaluating him and see him for a formal consultation.” Which makes me wonder: Can you imagine if doctors actually did everything lawyers told us to do?]

PCP: Well, he’s 100 years old, and the family doesn’t want him leaving the nursing home unless it’s a true emergency.*

[*A perfect example of how you don’t get the whole story from a curbside consult. “Quick question”… yeah right.]

Me: I see.

PCP: And I’d like to avoid giving him antibiotics, since last year he had C diff twice and it nearly killed him.*

[*See above comment about not getting “the whole story.”]

Me: Got it.

The lights dim in anticipation of the lecture. Various doctors, many of them cardiologists, begin heading for their seats, readying themselves for the lecture. Time is running out!

PCP: So, what do you think I should do?*

[*I knew it would come to this. Hey, I’m trying to be helpful! Really!]

Me: I guess you’re weighing the risks of giving him antibiotics — and causing another case of C diff — with the risks of undertreating a potentially invasive infection, MRSA.*

[*Look, I know this is an incredibly obvious thing to say. But what else can I do?]

PCP: I could have told you that, and I’m no ID specialist.*

[*He didn’t actually say this, but he was probably thinking it.]

Me: Ask me about evaluating chest pain. That’s much easier.

The lecture starts. It is excellent. But people immediately take out their smart phones and check their email and Facebook updates anyway.

February 10th, 2012

Boceprevir – PI Interaction: A “Dear Doctor” Letter We Didn’t Want To Get

By now I’m sure that most of you ID folks out there have received the following letter from Merck, the makers of boceprevir:

URGENT — IMPORTANT DRUG WARNING: VICTRELIS (BOCEPREVIR)

The purpose of this communication is to inform you of recent pharmacokinetic study results evaluating drug interactions between VICTRELIS, an oral chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3/4A protease inhibitor, and ritonavir-boosted human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease inhibitors … VICTRELIS reduced mean trough concentrations of ritonavir-boosted atazanavir, lopinavir, and darunavir by 49%, 43%, and 59%, respectively. Merck does not recommend the coadministration of VICTRELIS and ritonavir-boosted HIV protease inhibitors.

Boceprevir levels were also substantially lowered by lopinavir/r and darunavir/r.

Yes, we already knew that the telaprevir-boosted PI interactions were tricky. It’s basically atazanavir/ritonavir, no other options.

(Outside of the boosted PIs, you can use raltegravir or efavirenz with telaprevir, but the latter requires, 1125 mg three times/day, upping the cost by 50%. Gasp.)

The reason this “Dear Doctor” letter was so disappointing was that boceprevir was supposed to be easier in this regard. In this study presented at IDSA of peg/ribavirin + boceprevir for co-infected patients, all boosted PIs were allowed, only NNRTIs excluded. But that study was small (n=64), and in hindsight perhaps the slower-than-expected HCV RNA reduction had a pharmacokinetic explanation.

For now, the bottom line is that there really is no optimal HCV protease inhibitor for HIV/HCV co-infected patients, especially for those on a boosted PI.

And why careful assessment of those with HIV/HCV is critical, as many patients are stable enough to wait for the next wave of HCV drugs.

February 7th, 2012

Chronic Fatigue: Is There Hope After XMRV?

I’ve been following the chronic fatigue/XMRV story from the start, which was compelling for several reasons, including:

- A potential cause was identified of a very debilitating, mysterious illness.

- Lots of very smart ID people (including some of my colleagues) studied it.

- Media coverage, notably from the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, was particularly skillful.

In that last vein, the Times today has a fascinating summary of the current situation for this once promising link.

In a word, the link is kaput.

After numerous investigators were unable to duplicate the original results, Science issued an “Expression of Concern” about the paper they had published in 2009. Then in late December, that paper was fully retracted by the Editor of the journal, as was a key supporting paper — really the only supporting paper — that had been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Could things get any worse? Of course. Here’s what’s come of the lead investigator in the original Science paper:

Dr. Mikovits left her position as research director at the [Whittemore Peterson Institute] in a dispute over management practices and control over research materials. The institute sued her, accusing her of stealing notebooks and other proprietary items. Dr. Mikovits was arrested in Southern California, where she lives, and jailed for several days, charged with being a fugitive from justice.

Yikes.

But even with all these clouds, there’s an important silver lining to all this news nicely articulated by a noted virologist:

“The disease had languished in the background at N.I.H. and C.D.C., and other scientists had not been paying much attention to it,” said John Coffin, a professor of molecular biology at Tufts University. “This has brought it back into attention.”

I couldn’t agree more. And with that greater attention, perhaps we’ll see some discoveries that really help people.

January 29th, 2012

Pre-Super Sunday Scombroids

Some quick ID/HIV links while we await big guys playing the big game with a big (or at least bigger) ball.

Some quick ID/HIV links while we await big guys playing the big game with a big (or at least bigger) ball.

- Did you see how this doctor cheated Medicaid out of more than $700,000 by prescribing HIV meds to people who didn’t have HIV? Not surprisingly, he’s going to jail. Proof that if there’s money behind a program — no matter how beneficial — someone will figure out a way to scam it.

- Not only is there barely any winter this year, but there’s hardly any influenza. Not a single state is reporting widespread activity. But Google Flu doesn’t think it’s quite so remarkable, especially compared to last year where flu season peaked in mid-late February.

- What we’re not getting in flu, however, we’re definitely getting in norovirus activity, at least here in Boston. Last week someone in our office turned the color of a bedsheet, then disappeared home, only to returned a few days later weak, tired and 10 pounds lighter. And she didn’t even get to go on a cruise, though maybe that’s a good thing this year.

- Good brief piece in the Times about men of a certain age getting HIV. As the author awaits the results of his test, he writes “I was feeling an incipient sense of . . . failure.” That part particularly rang true, based on my clinical experience — these men lived through the horrible early years of the epidemic, and they feel like failures to get HIV now, after all these years. Lots of self blame.

- How about we all pick up one of these beauties for our hospitals before flu season kicks in? The Mold and Germ Destroying Air Purifier “eliminates up to 100% of airborne bacteria, mold, viruses, pet dander, dust mites, and pollen without making a sound or using a filter.” I guess the key is that “up to …” phrase. (Note to catalogue copy writers: doctors never use the word “germs” unless talking to non-medical people.)

For reference, today’s title was brought to you by the makers of the ABIM Recertification Exam, who truly have a thing for fish poisonings.

January 22nd, 2012

Generic Lamivudine Has Arrived

An e-mail from a patient last week:

Just got refills. Epivir is now generic??? Refill is simply labeled Lamivudine Tablets by Aurobindo Pharma USA, Inc …but made in India. Should I be concerned about that???

John

I told John (not his real name) not to be concerned — he is merely substituting the generic for the branded version, not switching from a fixed-dose combination or from a different drug (that drug being emtricitabine, or FTC).

With all the hoo-ha about generic atorvastatin, this one is much more under the radar. And the process to approval has not been smooth, as I wrote about here and here.

With all the hoo-ha about generic atorvastatin, this one is much more under the radar. And the process to approval has not been smooth, as I wrote about here and here.

But generic lamivudine for HIV treatment is a watershed moment nonetheless, since it’s really the first time there’s a generic antiretroviral that we might actually consider prescribing. (Zidovudine and didanosine have been generic for years.)

It will be fascinating to see how this plays out, both here in the US and in other developed countries.

January 21st, 2012

More Medical Testing! No, Less! You Decide

Fascinating Yin-Yang this week on the issue of medical testing. Want more? Want less?

First, this remarkable piece on retail medical labs, including a description of a company called ANY LAB TEST NOW:

Labs where folks can just walk in and order tests on themselves are popping up in retail centers across the country… At Any Lab Test Now, co-owner Anthony Richey pulls out a long sheet of paper with all the different tests his lab offers. There’s everything from an HIV screening to a “fatigue” panel. It looks like a sushi menu. “You say, ‘Well I want to check my diabetes, I want to get a hemoglobin A1C, and maybe I’ll check my lipid panel. And I’m a male over 40 so I’ll get my PSA checked,’ ” Richey says.

On the company’s web site, there are plenty of smiling, healthy people, plus these appealing claims: “No Doctor’s order needed … No appointment necessary … No insurance needed … Most results available in 24-48 hours.”

No doubt this is excellent customer service. But care to guess what that “Fatigue Panel” will set you back? That will be $499, thank you very much. But maybe they offer Gift Cards, that should help.

And if anything comes back abnormal?

If your results are ‘abnormal’ or ‘out-of-range’ from the normal, please contact your physician.

Joy.

It’s a poorly appreciated fact that the lower the likelihood of a disease being present, the greater the chance of a false-positive result.

Which is why no sensible physician would order all the components in the “Fatigue Panel” — which of course includes Lyme and EBV testing — without first taking a thorough history to determine if these diseases are even worth considering.

Meanwhile, over in the Annals of Internal Medicine, a group from the American College of Physicians this week argues for less testing:

The overuse of some screening and diagnostic tests is an important component of unnecessary health care costs… Efforts to control expenditures should focus not only on benefits, harms, and costs but on the value of diagnostic tests—meaning an assessment of whether a test provides health benefits that are worth its costs or harms.

What follows is an entirely sensible view of medical testing, with certain problematic, “low-value” tests called out for being wasteful — including the Lyme test mentioned in that “Fatigue Panel.”

And those false-positive tests, which retail labs must be generating by the crateload every day?

False-positive results are of concern because they often lead to further testing, which may be expensive and potentially harmful. They may also create anxiety for the patient and may lead to inappropriate treatment.

Which brings us back to the primary motivation of ANY LAB TEST NOW, which must be obvious by now:

“From a marketing standpoint it’s a good position to be in where you create a service, create a demand,” says Rodney Forsman, president of the Clinical Laboratory Management Association. “It becomes a consumable like Starbucks or bottled water.”

My advice? I strongly recommend that someone from ANY LAB TEST NOW contact the guys running GNC and explore co-franchising options.

They completely deserve each other.

January 18th, 2012

ID Case Conference Discussant Types

We specialists in Infectious Diseases love case conferences — especially those where the case is presented as an “unknown”, and we try to figure out the diagnosis from the history.

I suppose this isn’t very surprising, since ID cases in general are already among the most interesting in all of medicine. Those that are case-conference-worthy are particularly prime.

“Funny bug in a funny place,” was how one of my colleagues characterized these cases.

After the case is presented, the discussion by the participants takes various forms. I’ve been to hundreds of these conferences over the years, and have noted that the path taken by the discussants to arrive at the diagnosis (or not) varies quite a bit. There are certain styles, certain patterns of medical thinking in the conference room (rather than in the exam room or at the bedside) that show up again and again:

- The instinctual, “Here’s the diagnosis” approach. Very valuable when spoken by the Giants in the Field, who usually have several decades of clinical experience. These are short, targeted discussions that impressively even list the possible diagnoses in order of likelihood. Lou Weinstein was the quintessential “here’s the diagnosis” guy; sadly I only got to hear him discuss cases in the last few years of his distinguished career. Not surprisingly, this kind of medical reasoning doesn’t work nearly as well when attempted by relative beginners, e.g., a medical student, or even a second-year ID fellow. Bottom line: Beware the clinician in his/her 20s who begins a case discussion with the phrase, “In my clinical experience …”

- The comprehensive, “I’ve considered the entire universe of living organisms” approach. Can be both spectacularly interesting and educational or, conversely, crushingly, mind-numbingly boring. Mort Swartz (another Giant in the Field) discusses cases in this style, and I learn something from Mort every time — his knowledge not only of ID but all of Internal Medicine is awe-inspiring. However, my heart always sinks when a mere non-Mort mortal (couldn’t resist) starts a discussion by listing all the main categories of microorganisms as a prelude: “Let’s see, as potential causes for this person’s infected hip, there are prions, viruses, aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, higher bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, algae, protozoa, helminths, ectoparasites …” Time to get some more coffee.

- The prodding, “Let’s stop this game and tell me the diagnosis” approach. Usually goes something like this: A generic case is presented with minimal information — let’s say a man with a skin infection. No further history is given. And the discussant, not surprisingly, prods the presenter to give more information. “Any cats?” he/she asks, thinking Pasturella multocida or bartonella. “Any water exposure?” thinking Aeromonas hydrophila or Vibrio vulnificus. Because the discussant knows a simple skin infection is never going to make it to case conference, he/she keeps searching — there MUST be something interesting about the epidemiology. The presenter relents: “Well, as it turns out, the patient works as a clam shucker.” Bingo, Mycobacterium marinum or Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae.

- The diverting “I don’t know what this diagnosis is, but I certainly know a lot about other stuff, so let’s talk about that” approach. This clever strategy usually involves a true expert in a field forced out of his or her comfort zone. The world expert on salmonella, for example, suddenly finds him/herself discussing a hospital-acquired pneumonia in a patient who’s just had cardiac surgery. You can be sure that eventually the subject of intracellular pathogens (of which salmonella is an excellent example) will come up — somehow.

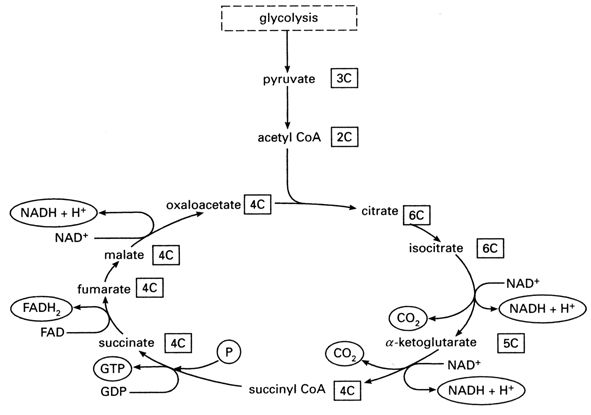

- The deer in a headlights, “You talking to me?” approach. Happens frequently when someone gets called on to discuss a case who’s not expecting it. Perhaps they’re junior faculty. Or just shy. Or maybe their mind has wandered, and they’re thinking about the Patriots’ playoff game, or whether to have another muffin, or the Krebs cycle. (I have never spontaneously thought about the Krebs cycle — see Figure above for a refresher.) And I’ve been informed by one of my most esteemed colleagues that some people just hate being called on, which I totally respect. (But others love yacking away during conference — they get offended if they’re not asked to opine — so it would be helpful to know how people feel about this. A green sticker on your white coat, perhaps, one that reads, “CALL ON ME!”) Suffice to say the startled discussant rarely gets the diagnosis correct, but they are often inadvertently funny.

Here’s a tip — if you’re ever asked about a case during conference, and you haven’t been listening, and the person being discussed is acutely ill, just say, “It could be staph.” If chronically ill, “It could be TB.” You will never be wrong.

What kind of discussant are you?