An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

June 15th, 2012

ID Learning Unit — The D Test

I suppose it’s not surprising that we’d follow-up the Etest with the D test, though perhaps if I were being alphabetical, the order would have been reversed.

The D test is important, because it screens for a form of clindamycin resistance in MRSA that might otherwise not be detected — the “inducible” kind, which can be associated with treatment failures. About half of MRSA isolates have this form of resistance.

The D test is important, because it screens for a form of clindamycin resistance in MRSA that might otherwise not be detected — the “inducible” kind, which can be associated with treatment failures. About half of MRSA isolates have this form of resistance.

Here’s how it works:

- Take some erythromycin-resistant, clindamycin-“sensitive” MRSA, spread it on a culture plate

- Drop an erythromycin disk on the left side of the plate, and a clindamycin disk on the right

- If there’s a flattening of the zone of inhibition between the two disks, then the test is positive, confirming inducible clindamycin resistance

- Report that bug as clindamycin resistant

First, critical thinkers will wonder why this is important, since we obviously don’t give erythromycin with clindamycin to an actual patient. My big-picture explanation is that it’s a marker for easily inducible resistance even without the erythro being present.

And second, note the critical step of putting the clindamycin disk on the right — otherwise the shape of the zone of inhibition won’t be a “D”, and everyone will be confused because who knows what to call that shape.

(That second part was a joke.)

June 13th, 2012

Questions About HIV Cure, and a Very Funny Quote

The single case of HIV cure following allogeneic bone marrow transplant is in the news again, this time because of data just presented at “The International Workshop on HIV and Hepatitis Virus Drug Resistance and Curative Strategies” (formerly known as the “HIV Resistance Workshop” — how’s that for rebranding?).

The single case of HIV cure following allogeneic bone marrow transplant is in the news again, this time because of data just presented at “The International Workshop on HIV and Hepatitis Virus Drug Resistance and Curative Strategies” (formerly known as the “HIV Resistance Workshop” — how’s that for rebranding?).

I’m not at the meeting, which is too bad since they often have it in splendid locations.

But from what I gather based on the report, here are the key findings in the study:

- The patient remains off antiretroviral therapy, with a normal CD4 cell count

- He has generously submitted multiple specimens for research analyses at multiple different time points

- Highly sensitive assays of various sorts have been performed at several labs

- HIV RNA has been detected in plasma in 2 (of 4) labs from 3 different time points; levels are lower than those typically seen in virologically suppressed patients on ART

- HIV DNA was detected in a rectal biopsy sample by one lab

- No HIV has been detected in CSF or peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- No replication-competent HIV has been isolated

My gut feeling is that the findings are potentially real, but unlikely to be of much clinical significance if virus can only be detected intermittently by special assays, especially since he’s been off all HIV treatment for more than 5 years.

But they may not be real — we need to remember that a false positive test result is more likely when the test’s sensitivity is cranked up and it’s performed multiple times.

Or as more colorfully put by Doug Richman:

If you do enough cycles of PCR, you can get a signal in water for pink elephants.

And if this interesting presentation tells us anything, it’s that defining success in any study of an HIV cure strategy is going to be very, very difficult.

June 12th, 2012

ID Learning Unit — The Etest

Every year I attend on the general medical service, so it gives me a chance to work directly with the medical residents — and to brush up on my non-ID-related Internal Medicine.

Every year I attend on the general medical service, so it gives me a chance to work directly with the medical residents — and to brush up on my non-ID-related Internal Medicine.

In exchange for what they teach me, each day on rounds I try to tell them about at least one ID-related thing that they may not know. Since I do this in the spring, they’re awfully sharp. Fortunately, I’ve been doing this ID stuff a long time, so can usually find something.

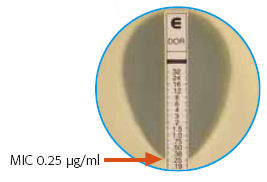

Today’s learning unit was the “Epsilometer Test, or “Etest” — that brilliantly simple way of estimating the MIC of an antibiotic to an organism, by using a drug-impregnated strip that has a gradient of concentration, from high to low. Find where the “elipse” of inhibition crosses the strip, and presto! There’s your MIC.

We take for granted that this method is readily available and, for the most part, clinically valid. It’s worth remembering, however, that when it debuted in the late 1980s/early 1990s, it was considered pretty slick and not entirely trustworthy.

And there’s still some debate about how reliable it is, especially with MRSA.

If you want to learn how to do it, watch this movie.

June 8th, 2012

SPARTAN: Two-Drug, NRTI-Sparing Strategies Continue to Disappoint

Just published is the cleverly named “SPARTAN” study — spartan because it leaves out both NRTIs and ritonavir — and the results are very interesting.

Just published is the cleverly named “SPARTAN” study — spartan because it leaves out both NRTIs and ritonavir — and the results are very interesting.

Ninety-three treatment-naive HIV-positive study subjects were randomized 2:1 to receive either a two-drug regimen of raltegravir 400 mg BID + atazanavir 300 mg BID, or a standard regimen of TDF/FTC + boosted atazanavir. (The higher ATV dose in the two-drug arm targeted ATV exposures comparable to those achieved by ritonavir-boosting.)

At week 24, virologic suppression rates numerically favored the two-drug regimen (75% vs 63%); as a small pilot study, the trial was not powered for a statistical comparison between the two arms. As has been observed in other studies of integrase inhibitors, the non-integrase group had a slower initial response and appeared to be catching up.

Despite these early favorable results, there were 6 virologic failures in the RAL + ATV group — vs only 1 in the standard arm — and 4 of these failures showed evidence of raltegravir resistance. Notably, all 4 of these patients with resistance had baseline HIV RNA > 100,000, a similar finding to ACTG 5162 (which examined RAL + darunavir/r). Rates of grade 3-4 and grade 4 hyperbilirubinemia were also higher in the ATV + RAL arm. Based on these efficacy and safety results, the sponsor elected to terminate the study.

As I’ve noted before, initial two-drug HIV therapy without NRTIs hasn’t fared well, even when it includes our best drugs. In addition, we still don’t know why these two-drug regimens don’t do as well, especially in patients with high viral loads.

Furthermore, the protective effect that boosted PIs have on the development of NRTI resistance doesn’t apply either to NNRTIs (as shown in ACTG 5142) or to raltegravir (again, ACTG 5162). And though in SPARTAN ritonavir-boosting wasn’t used, it doesn’t appear we can blame PK, as ATV exposures indeed were comparable to those seen with ATV/r dosed at 300/100 mg daily. Do the NRTIs provide some key antiviral component mechanistically? Do we just not have the right two active drugs? Or is there something magic about using 3 rather than 2 drugs, regardless of mechanism of action?

Suffice to say, the results of the fully powered NEAT study — which compares RAL to TDF/FTC, with all study subjects receiving boosted darunavir — will be of great interest, as will a similar study that uses maraviroc instead of raltegravir.

June 6th, 2012

A Fun Internet Poll for ID Nerds

Over on Medscape, one of my ID heroes, John Bartlett, has a new series called, “The Medscape Awards in Infectious Diseases” and it looks like a winner.

Here’s how it works:

The Medscape Awards in Infectious Diseases is a new series that will honor the greatest achievements in the field of infectious diseases during 1980-2012. John G. Bartlett, MD, Professor of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, identified 8 key categories for these infectious disease awards… Readers will be asked to select the candidate that they believe is most worthy of this title, and then Dr. Bartlett will reveal his personal choice and the reasons for that choice.

OK, I’m game — for two reasons. First, practically anything that has John’s distinctive combination of scholarliness and practicality behind it has got to be good; and second, I am a towering nerd when it comes to Infectious Diseases. I admit it.

So bring on the first category — “Bacterium”.

The question is, “What do you believe was the most important discovery of a new bacterium during the time period 1980-2012?” Here are the choices, and my thoughts about each one:

The question is, “What do you believe was the most important discovery of a new bacterium during the time period 1980-2012?” Here are the choices, and my thoughts about each one:

- 1980: Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease) — has spawned an entire parallel universe deftly described here.

- 1982: Escherichia coli O157:H7 (hemorrhagic colitis) — posits the eternal question, can a person really learn to prefer a hamburger well-done? Here’s my opinion.

- 1983: Helicobacter pylori (peptic ulcer disease) — one of the true oddities of helicobacter is that ID doctors know nothing about it; it’s like asking an MD about teeth.

- 1986: Chlamydia pneumoniae (atypical pneumonia) — also the cause of coronary artery disease … NOT.

- 1999: Bartonella henselae (cat-scratch disease) — this is my first Ted Nugent citation on this blog.

- 2000: Tropheryma whipplei (Whipple disease) — number of cases most ID doctors personally have diagnosed = zero. Which equals the number of Whipple Procedures they have done, too.

- 2000: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (USA 300 strain) — USA 300 sounds like a motor race, and not surprisingly, it actually is one too.

- 2000: Clostridium difficile NAP-1 strain (C difficile epidemic) — probably the best reason out there to avoid unnecessary antibiotics; I’d be shocked if we’re still using antibiotics as our primary treatment for C diff in 5 years.

- If not listed here, tell us about your choice — I would consider Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase bacteria (KPCs), since they’re a glimpse of a post-antibiotic era, or Streptococcus gallolyticus, because it’s the new name of Strep bovis that I can never remember, or if we’re talking new names in the past 20 years, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, since it’s such a wonderful mouthful to say.

So my vote?

June 2nd, 2012

Cryptococcal Meningitis Study Stopped — Early HIV Therapy Clearly Harmful

From NIAID, an important clinical trial has been stopped early:

The Phase IV study … was evaluating whether HIV-infected participants hospitalized with cryptococcal meningitis (CM) but not yet taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) would improve their chances of survival if they began ART while receiving CM treatment as inpatients compared with the standard practice of beginning ART as outpatients, approximately five weeks after receiving CM treatment. Two reviews of the COAT trial’s safety and effectiveness data last month by an independent data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) found substantially higher mortality rates among the 87 participants who received early ART compared with the 87 participants who received delayed HIV treatment.

More details on the study design can be found here, and we’ll undoubtedly hear and read additional details on the results in an upcoming meeting and when the paper is published. But since it was stopped after only 174 (out of a planned 500) enrolled, the difference between the two strategies must have been really huge. [See edit below.]

Until then, we can postulate that ART-induced immune response — IRIS — triggered inflammation, which could have worsened intracranial pressure and other manifestations of cryptococcal disease. Inflammation is just bad news in meningitis. This could explain why crypto and perhaps TB meningitis seem to be the exceptions to the rule that early ART is beneficial with acute OIs — a strategy confirmed now in several clinical trials (ACTG 5164 and these three TB studies: SAPIT, STRIDE, and CAMELIA).

Until then, we can postulate that ART-induced immune response — IRIS — triggered inflammation, which could have worsened intracranial pressure and other manifestations of cryptococcal disease. Inflammation is just bad news in meningitis. This could explain why crypto and perhaps TB meningitis seem to be the exceptions to the rule that early ART is beneficial with acute OIs — a strategy confirmed now in several clinical trials (ACTG 5164 and these three TB studies: SAPIT, STRIDE, and CAMELIA).

Importantly, the study confirms the results of this other cryptococcal meningitis study (which amazingly was led by one of our ID fellows before she started fellowship — how’s that for impressive?), but differs in at least two important ways: First, initial therapy was with the standard-of-care amphotericin B and not fluconazole; and second, the ART was efavirenz- not nevirapine-based. Both of these address at least some of the concerns about the earlier study’s generalizability. A5164 did not find that early ART was harmful in crypto meningitis; however, the number of study subjects with cryptococcosis was relatively small (35 out of 282).

Though the COAT trial was conducted in Uganda and South Africa, the results have immediate applicability to practice world-wide. Early ART in cryptococcal meningitis is clearly harmful, and clinicians should delay starting ART for at least 5-6 weeks in their patients with the disease.

And the study reminds us more broadly that critical studies on the optimal management of HIV-related OIs will necessarily need to come from outside the United States and Western Europe.

[Edit: David Boulware, the PI of the COAT trial, kindly provided a bit more data on the study results. He noted that the “absolute difference in 6-month survival is approx. 15% between the two arms (with ongoing follow up still occurring through October 2012)”, which is perhaps not as big an effect as I had anticipated. However, the message remains the same – early ART after cryptococcal meningitis decreases survival, and should be avoided. He also noted that linkage to outpatient HIV care remains a very important consideration for delayed ART.]

May 30th, 2012

Little Fluffy Baby Chicks Spread Deadly Intestinal Infection

Sorry for the headline, but that was the first thing I thought of when reading this paper just published in the New England Journal of Medicine:

In this report, we describe a prolonged and ongoing multistate outbreak of human salmonella infections primarily affecting young children and linked to contact with live young poultry from a single mail-order hatchery… Because only a portion of salmonella infections are laboratory confirmed, it is likely that thousands of additional unreported infections occurred in association with this outbreak.

To be fair, no one actually died from this outbreak (though 36 patients were hospitalized, most of them 5 years old or younger).

Regardless — it’s hard to imagine baby chicks as vectors for anything, let alone something as unsanitary as salmonella. They’re so cute!

But when you think about it for even a few seconds, why should they be any cleaner than grown-up chickens — which are decidedly not clean.

So the next time you send the kids out to the backyard flock to check for fresh eggs, and they might stop on the way to play with the chicks, pay attention to these wise folks from the CDC, who warn:

Consumers wishing to reduce their risk of illness should practice meticulous hand hygiene and encourage this behavior in children. High-risk groups, including children younger than 5 yearsof age, elderly persons, and immunocompromised persons, should not handle or touch chicks, ducklings, or other live poultry.

So add this to the long (and growing) list of high-risk behaviors.

May 25th, 2012

Generic Nevirapine Now Available — But the Big One is Next Year

As I’m sure you’ve heard from your patients — as I did — lamivudine (3TC) is now available generically.

Now comes news of the release of several generic formulations of nevirapine (NVP), an effective but always somewhat overshadowed medication. Since its approval way back when in 1996, there has always been a solid reason to pick something else.

Why? Here are a few reasons, some scientific, some accidents of HIV history, some just gut responses:

- The first studies of NNRTIs showed that resistance to the drugs developed very quickly, often within days. Since NVP was the first in this class of drugs approved, it always carried that baggage of “low resistance barrier” more than other drugs.

- Remember this whole “convergent combination therapy” saga? The message was that if there was enough selective pressure on the same target — here reverse transcriptase, using AZT, ddI, and NVP — HIV could not grow in vitro at all, since the virus paid such a penalty for accumulating resistance mutations. The authors (many of whom are still colleagues of mine) urged caution in interpretation of results, but that didn’t stop it from being front page news — and more — which made it all the more heartbreaking when the paper was retracted 6 months later.

- Nevirapine was approved right after indinavir, the first PI that really put combination antiretroviral therapy on the map. It didn’t matter that in hindsight NVP had many advantages over indinavir (fewer pills, fewer side effects, better metabolic profile, no need for a quart of water a day, easier to take) — NVP was hugely overshadowed. In hindsight, possibly the reason that indinavir seemed to be a more effective drug was that pivotal trials with indinavir included ZDV/3TC, but with nevirapine ZDV/ddI. Which combination of NRTIs would you prefer?

- The approval of efavirenz in 1998 was another reason not to pick NVP. Based on experience with NVP and delavirdine, I never thought any drug from this class could be more effective than a PI. Indeed, I was highly skeptical until this study, with its surprising finding that efavirenz was in fact better than indinavir. Now that efavirenz has pretty much become the gold standard “key third drug” in HIV treatment — still never beaten in a primary analysis of any HIV study — I’m a believer!

- Nevirapine hypersensitivity — rash, fever, hepatitis — is scary and potentially fatal, and the two-week dose escalation sounds simple but is not always so easy for patients to get right. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis are also concerns. Never mind that rates of these reactions are low when NVP is prescribed appropriately, these severe side effects obviously are a deterrent to using the drug. Anecdote: A patient once came to me with an ad from a magazine for NVP, saying “Don’t give me this one — I know someone who nearly died from it.”

- Single-dose NVP for prevention of maternal to child transmission certainly works, is safe, cheap, and probably has saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of children in developing countries. But the take-home message for most clinicians reinforced the resistance problem. And no one would recommend it in settings that had access to fully suppressive regimens.

- These weird reports (here for example, or more recently here) of virologic failure with resistance when NVP is given with TDF and 3TC remain mostly unexplained, but certainly would make me hesitant to use this combination, especially in patients with high viral loads.

- Prior treatment failure with efavirenz doesn’t typically give a patient resistance to etravirine, the second-generation NNRTI. Nevirapine, however, often selects for Y181C, which along with other mutations makes etravirine substantially less active.

Among the above, probably the biggest challenge facing NVP was #4 — can we finally say that efavirenz is just a much better drug than nevirapine? Maybe not for all people, but for most of them. For further evidence, here’s Chuck Hicks’ nice summary of a large cohort analysis comparing the two drugs.

All in all, I therefore doubt that generic NVP is going to have a whole lot of influence on HIV prescribing in the United States. Those who are on branded NVP and doing well will switch to it (or more accurately, “be switched to it”) saving some drug costs.

But when efavirenz goes generic — some time next year or the year after? — that will be big news. And raise all kinds of interesting questions.

May 20th, 2012

News on HIV and HCV Testing, and in Praise of Accurate Screening Tests

Two recent news items reminded me how lucky we are to have some very accurate screening tests for certain infectious diseases.

Two recent news items reminded me how lucky we are to have some very accurate screening tests for certain infectious diseases.

The news:

- An expert FDA panel backed approval of the first true home test for HIV, the OraQuick mouth swab test. Approval of OraQuick for home use may occur later this year. While home testing for HIV exists already — HomeAccess — the OraQuick test will be the first that does not require submitting the specimen to a central laboratory; the user wil be able to get the result at home, much like a pregnancy test.

- The CDC is recommending that all Americans born between 1945 and 1965 be tested for hepatitis C. With 1 in 30 from this age group infected, and increasingly effective therapies available now and the near future, this testing strategy (which involves a simple blood test done by a clinician) could dramatically reduce liver-related deaths. (Note that I can’t find this recommendation on the actual CDC site — I know it’s somewhere, but not here or here or here. Oh well.)

Neither one of these tests is perfect, but they’re definitely good enough to be used broadly, with reactive results triggering further testing to confirm or rule out infection. Furthermore, confirmatory tests for HIV and HCV are extremely accurate. In other words, sorting out real HIV or HCV infection from a false-positive screening test is generally quite straightforward.

Now compare and contrast with the disease mentioned in this email query from a primary care provider:

Hi Paul, quick question. 49 year old healthy guy, fatigue and palpitations on and off the past year; normal exam and ECG. Says other people in his neighborhood have Lyme, so I sent the test. ELISA is positive, immunoblot has one IgM band, all IgG bands negative. Could this be Lyme? Should I just give him doxy? For how long?

What did Charlie Brown say when Lucy pulled away the football?

May 16th, 2012

Azithromycin Linked to Cardiovascular Death — Not A Placebo After All

I’ve commented before about azithromycin, that remarkable antibiotic that clinicians seem to prescribe for, gosh, you-name-it.

I’ve commented before about azithromycin, that remarkable antibiotic that clinicians seem to prescribe for, gosh, you-name-it.

But a paper just published in the New England Journal of Medicine links use of azithromycin to an increased risk of cardiovascular death, a reminder that “azithro” is in fact a drug — and that all drugs have side effects.

A few more musings on this extremely popular antibiotic:

- Has there been anything even close to the universal “penetrance” of the 5-day, 6-pill “Z-Pak” in terms of outpatient antibiotic prescribing? Oddly enough, the first time I wrote for it way back in the early 1990s, the patient I gave it to thought he was being ripped off — not enough pills!

- Of course, that didn’t last long, many patients now ask for a “Z-Pak” by name. The marketing genius who came up with the “Z-Pak” should win the advertising equivalent of the Nobel Prize, even if he/she would fail a first-grade spelling test.

- The ubiquitous toy zebras probably didn’t hurt pediatric prescribing either. These trinkets are now forbidden, but you can pick one up on eBay if you’re feeling nostalgic.

- Initially, cost-cutters tried to get clinicians to prescribe erythromycin over azithro (and clarithro) since the newer macrolides were so much more expensive. Talk about a losing battle — sometimes newer is not just costly, it’s costly and better. (Ditto fluconazole when it replaced ketoconazole.)

- Now that azithromycin and clarithromycin are both generic, does anyone regularly use clarithromycin anymore? Yes, it’s more active versus atypical mycobacteria, but hardly enough so to make it worth the increased drug-drug interactions, QT prolongation, excess mortality risk (as seen in prospective studies like this one), and peculiar taste disturbance. (It was with clarithromycin that I learned the word dysgeusia — it means distortion of taste — and a famous mycobacterial researcher has a fascinating anecdote about how bizarre champagne tastes when accompanied by a side of Biaxin.)

- Department of Irony: Azithromycin was studied as treatment to prevent cardiac disease. You remember, treat Chlamydia pneumoniae, that notorious “cause” of atherosclerosis, and reduce cardiac events. (It didn’t work.)

- Little-known fact: Azithromycin was developed by a then-small Croatian pharmaceutical company named Pliva in the 1970s, with a world-wide patent in 1981 — 10 years before it was FDA-approved in the USA. At its peak, Pfizer was making more than $1 billion/year on azithromycin sales and, of course, sharing some of that with Pliva (and making stuffed zebras).

- The downside of all this azithromycin use? Predictably, increased rates of clinically important resistance — especially Strep pneumo and group A strep. Hard to believe that second-line treatment for pneumococcal pneumonia, back when I was in medical school, was erythromycin. Yes, I might be old.

If there’s a silver lining to this report in the NEJM, it’s that clinicians will stop prescribing azithromycin for conditions that clearly don’t need it — which is just about every uncomplicated outpatient respiratory infection.

Hey, we can dream, can’t we?