An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

September 19th, 2012

It’s Time to Dump the HIV Western Blot

Hard to believe, but we have to get rid of the HIV Western blot — at least as our HIV confirmatory test.

Here’s why (case adapted from several seen the past few years; I’m sure most of you have seen similar):

- 30-year-old man, high risk for HIV. He’s worried he might have become infected due to recent exposures, so he requests testing at a community health center.

- The clinician does an oral rapid test, which is positive, then sends a blood sample to the lab for confirmation.

- The ELISA test is also positive, so the lab sends this sample off-site for confirmation by Western blot.

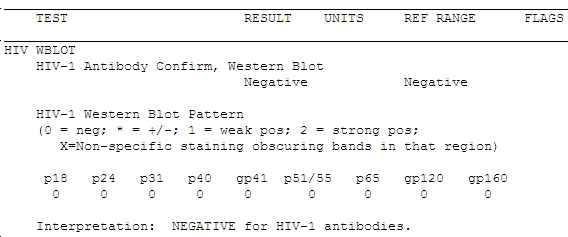

- One week later (the Western blots always take longer than you think they should), the result comes back:

Does that worry you? If not, it should — the guy’s HIV viral load was > 1 million copies/mL. Not only that, but the clinician who did the testing told him that he should return in 6 weeks for a repeat test to see if he fully seroconverts. The patient suspected something might be wrong with that advice (you think?) and sought a second opinion from one of my colleagues, who sent the viral load.

The case highlights what Bernie Branson from the CDC has been telling us for years, which is that the Western blot is lousy at detecting recently acquired HIV. (Great CROI 2012 presentation by Bernie here, when you have a moment.) The Western blot is barely more effective as a “confirmatory” test in this setting than if the sample had been sent for Tropheryma whipplei antibody — and we all know how often those are helpful.

(Little inside ID joke there.)

The fact is that there is a 40-day delay from when “4th Generation” antigen/antibody combination test turns positive to when the Western blot does so. That’s a long time for a person not to know whether he/she has HIV, especially since this is the most contagious period in all of HIV infection.

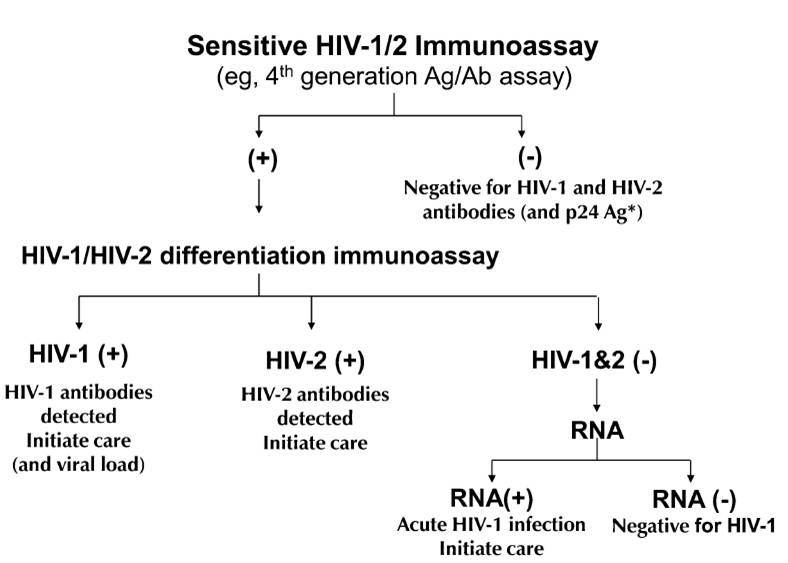

So what should we do? Chaired by Eric Rosenberg, The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) issued a new testing algorithm (M53-A) in July, and the CDC will soon follow with similar recommendations. In essence, the most important algorithm will look like this (figure from Bernie’s excellent 2010 paper):

One immediate problem is that most labs don’t have an “HIV-1/HIV-2 differentiation immunoassay”. Only one such test — the Bio-Rad Multispot HIV-1/HIV-2 Rapid test — is FDA approved, although apparently another test is in the late stages of development.

But until such assays are widely available, here’s some practical advice we can give clinicians today:

- Current HIV screening tests (ELISA IgM or ELISA/Ag combinations) are much more sensitive than the Western blot.

- Every case with a positive screening test but a negative Western blot must have an HIV viral load.

- Every case in which HIV acquisition might have been recent — symptoms of acute HIV, or HIV testing in the context of a recent STI (especially syphilis), or known recent negative HIV test — should have an HIV viral load sent along with HIV antibody testing (or at the very least, be tested using a 4th Generation combined antigen/antibody test).

Check out this article from the March 2012 issue of CAP Today for a complete discussion.

And to the HIV Western blot, hey, it’s been great — I thank you for your 20+ years of excellent service! Now it’s time for us to move on.

September 11th, 2012

Are Fluoroquinolones Really More Dangerous Than Other Antibiotics?

In today’s New York Times, health writer Jane Brody slams quinolone antibiotics:

In today’s New York Times, health writer Jane Brody slams quinolone antibiotics:

Part of the problem is that fluoroquinolones are often inappropriately prescribed. Instead of being reserved for use against serious, perhaps life-threatening bacterial infections like hospital-acquired pneumonia, these antibiotics are frequently prescribed for sinusitis, bronchitis, earaches and other ailments that may resolve on their own or can be treated with less potent drugs or nondrug remedies — or are caused by viruses, which are not susceptible to antibiotics.

True enough — although one could say the same thing about every antibiotic, which is something most ID doctors do on a regular basis. Sometimes this convinces patients who request antibiotics to go without, sometimes not.

Brody then goes on to describe several of the more notable — plus some very rare — quinolone side effects, including:

- renal failure

- retinal detachment

- C diff

- tendonitis and tendon rupture

- neuromuscular blockade

- CNS side effects

- rashes and phototoxicity

But the centerpiece of the article is a case history of someone who developed severe, multisystem, and debilitating side effects after the first, and especially the second, dose of levofloxacin:

After just one dose, he developed widespread pain and weakness … But the next pill, he said, “eviscerated” him, causing pain in all his joints and vision problems. In addition to being unable to walk uphill, climb stairs or see clearly, his symptoms included dry eyes, mouth and skin; ringing in his ears; delayed urination; uncontrollable shaking; burning pain in his eyes and feet; occasional tingling in his hands and feet; heart palpitations; and muscle spasms in his back and around his eyes.

It’s great that the downside of inappropriate antibiotic usage is getting more attention (normal bacterial flora are your friends), and of course fluoroquinolones are by no means 100% safe, as I noted here.

But I wonder — are they truly more dangerous than other antibiotics? Or is this a matter of heavy usage of relatively new drugs, hence more notoriety?

What do you think?

September 8th, 2012

People Fear EEE and West Nile, but not Influenza — Can Someone Explain Why?

OK, here’s a quick quiz — match the viral infection with the average annual US deaths:

| 1. Eastern Equine Encephalitis | A. 36,000, mostly in the elderly |

| 2. Influenza | B. < 10, mostly in the elderly |

I know, it was an easy one — 1 goes with B, and 2 with A. Here’s a good reference for more on flu deaths, if you don’t believe me.

I completely understand it’s been a bad year for arbovirus infections, in particular West Nile.

Yet as we’ve just had our first deaths from EEE and West Nile in the state, prompting widespread news coverage, mosquito spraying, and warnings from the Department of Public Health, the annual flu vaccine has quietly arrived.

And once again it’s remarkable how many people refuse the vaccine. Can someone please explain?

Thank you.

September 1st, 2012

CROI 2013: March 3-7, Atlanta

August 31st, 2012

“PEARLS” Study a Massive, Impressive Accomplishment

One of the most frequent criticisms of randomized clinical trials of HIV therapy is that certain patient groups — in particular gay men — are over represented compared to the HIV population as a whole. For example, in the recently published and presented clinical trials of the Quad and dolutegravir, women accounted for < 20% of the study population, despite representing approximately 50% of those living with HIV worldwide.

One of the most frequent criticisms of randomized clinical trials of HIV therapy is that certain patient groups — in particular gay men — are over represented compared to the HIV population as a whole. For example, in the recently published and presented clinical trials of the Quad and dolutegravir, women accounted for < 20% of the study population, despite representing approximately 50% of those living with HIV worldwide.

Now along comes the The Prospective Evaluation of Antiretrovirals in Resource Limited Settings (PEARLS) study, and let no one criticize this trial as not being representative! Conducted in Brazil, Haiti, India, Malawi, Peru, South Africa, Thailand, the United States, and Zimbabwe, the study enrolled 1,571 HIV-1-infected treatment-naive patients, of whom 47% were women. They were randomized to one of three treatments:

- ZDV/3TC + EFV

- TDF/FTC/EFV

- ddI + FTC + ATV

50% were African race, 23% Asian, and 20% Hispanic — remarkably diverse demographics.

A DSMB stopped the study early after observing a greater number of virologic failures in the ATV arm, and a lower than expected number of failures with the other two regimens. Furthermore, while the two EFV arms were comparably effective from a virologic perspective — a finding similar to the prior 934 study, where virologic failures were not significantly different — the safety of TDF/FTC/EFV was significantly better than ZDV/3TC + EFV, particularly in women. Interestingly, women also did better than men on the atazanavir regimen; the reason for this difference is being investigated, and may be related to fact that levels of PIs can be higher in women than men.

The importance of this study is that it greatly strengthens the evidence that TDF/FTC/EFV is truly our gold standard for HIV treatment across a broad range of patients and in multiple settings. It also demonstrates a research collaboration on a massive scale, involving the NIH, several pharmaceutical companies, literally hundreds of investigators at dozens of study sites, and 9 countries!

Additional analyses from this impressive trial are eagerly awaited.

August 28th, 2012

“Quad” Approved by FDA

We now have a third single-pill treatment available for HIV treatment, co-formulated tenofovir/emtricitabine/elvitegravir/cobicistat. From the FDA announcement:

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today approved Stribild (elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate), a new once-a-day combination pill to treat HIV-1 infection in adults who have never been treated for HIV infection. Stribild contains two previously approved HIV drugs plus two new drugs, elvitegravir and cobicistat … Together, these drugs provide a complete treatment regimen for HIV infection.

A few quick thoughts about this approval, with the disclosure that I was an investigator on one of the phase III studies that led to its approval:

- The combination — which I’ll continue to call “Quad”, at least for now — is just as active virologically as two preferred initial regimens — TDF/FTC/EFV (the first of the single pill treatments), and TDF/FTC + atazanavir/r (the most commonly used boosted PI regimen).

- The side effect profile was different from TDF/FTC/EFV, with less CNS disturbance and rash, and more nausea; the side effects were quite similar to the boosted ATV/r regimen — except for hyperbilirubinemia from atazanavir, of course — possibly because cobicistat and ritonavir are related.

- The renal issues with cobicistat are potentially tricky, as it causes a 0.1-0.2 mg/dL increase in creatinine that is related to inhibition of tubular secretion of creatinine, and hence does not actually decrease GFR. As a result, the regimen should not be used in patients with impaired renal function, and they were not studied in the Quad trials.

- One potentially helpful number to remember is 0.4, as the small number of patients with tenofovir tubular toxicity in the Quad studies also had an increase in serum creatinine of at least this much — hence distinguishing them from the more benign smaller increase from cobicistat.

- Separate studies of Quad in patients with renal insufficiency and in women are planned (only a small proportion of study patients were women).

The bottom line is that Quad is an effective, very convenient option for initial HIV treatment. I suspect how much traction it gets from providers will depend on their experience in clinical practice related to safety and tolerability, and in the future to pharmacoeconomic factors, as generic antiretroviral strategies will become increasingly available that might challenge use of coformulated regimens.

(How about that name, “Stribild”? Pronounced with a long or short “I”? Wonder what the runner-ups were for that brand name.)

August 25th, 2012

On HCV, These Questions Three

In the fastest-moving area of ID drug development, answers are eagerly sought to the following questions three:

In the fastest-moving area of ID drug development, answers are eagerly sought to the following questions three:

- What does the bad news on BMS-986094 — formerly INX-189 — mean for other investigational HCV nucleotides? Severe cardiotoxicity, fatal in one case, has ended the drug’s development. Importantly, nothing similar has thus far been observed with the structurally-similar IDX184, but that drug has been placed on “clinical hold” by the FDA. By contrast, the nucleotide GS-7977 is apparently different enough chemically that studies are for now continuing. One take-home message: drug development is risky business.

- When will the alphabet soup of terms used to describe HCV treatment response be abandoned? HCV treatment either works, and you’re cured, or it doesn’t. But because the treatment is so cumbersome and so long, there’s a whole slew of ways to describe how things are going before you get to that point. Let’s see, there’s RVR (rapid virologic response, or no virus detected at 4 weeks); eRVR (extended rapid virologic response, or no virus detected at weeks 4 and 12 — used in this study of daclatasvir); EVR (early virologic response, which really isn’t that early, because it’s week 12, and it can be either pEVR — for “partial” — which means HCV RNA drops by more than 2 log but is still detected, or cEVR — for “complete”, which means it’s undetectable); ETR (end of treatment response, or no virus detectable at end of treatment); and of course SVR (sustained virologic response, now available in many flavors, depending on the week after stopping treatment you want to measure it — 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 24,etc). For now, with IF/RBV +/- telaprevir/boceprevir and “response-guided” therapy still ruling the day, we’re stuck with this mish-mosh of terms, but I suspect most of this stuff will be irrelevant pretty soon, except for the bottom line — how many are cured? Doesn’t that sound better than “How many are SVR-12’d?”

- So when precisely will these new drugs become available? Seems pretty obvious right now that if you’ve got HCV and can wait for better treatments, you should. Treatment became more effective with telaprevir and boceprevir, but it also got more complicated, toxic, and expensive. Things have to get better, and they will — especially with interferon-free options. Regardless, no one knows exactly when these new drugs will be available for use outside of clinical trials — 2013-2014 a broad estimate — and all kinds of things could hold up their approval (see #1 above). Plus, some patients can’t and shouldn’t wait for better options because they have advanced liver disease. Just this last week, two such individuals came in for evaluation — both with HIV, both with prior treatment failure on IF/RBV, both with Stage 3/4 fibrosis on liver biopsy. Should they wait for daclatasvir, GS-7977, TMC-435, ABT-450/r + ABT-333, etc? Probably not.

August 17th, 2012

Beeper, An Enthusiastic Farewell!

August 17, 2012, is the first day in over 25 years that I left for work without clipping a beeper to my belt.

Yes, our hospital now offers paging through cell phones. Eureka!

As I’ve written before, it was a long time coming. Here are some advantages:

- Spares the embarrassment of wearing a circa-1980s device around non-MD colleagues.

- Portrays a more slimming profile for the fashion-conscious.

- Reduces electromagnetic waves so close to reproductive organs.

- Saves money on AA batteries.

- Diminishes landfill contamination from discarded alkaline cells.

- Decreases the number of items one risks losing, breaking, dropping in the toilet, etc.

- Sheds unfortunate association with drug dealers.

I’m sure there are more, but regardless, I was bound to be an early adopter of a non-beeper life. Yesterday, after passing in the beeper, I almost expected there to be some sort of ritual ceremony, something akin to what they just did in London at the end of the Olympics.

Here then, for posterity’s sake, is the very first page I received on my cell phone, courtesy of our Education Coordinator Margot:

For the record, the answer to my question was yes — she did get my text response in her email. Yet another benefit of chucking the one-way pager.

August 15th, 2012

Brush with Greatness: Atul Gawande

I was an English major in college, so when my acceptance to medical school (miraculously) arrived, several people gave me books written by doctors about their experience in the medical profession.

I was an English major in college, so when my acceptance to medical school (miraculously) arrived, several people gave me books written by doctors about their experience in the medical profession.

“See,” these gifts implied, “Just because you’re going to medical school doesn’t mean you need to become a science drone. Doctors can write too!”

Sure, doctors can write — but can they write well?

Debatable — confess I’m not a big fan of most books or articles written by doctors. First, the tone in many of them is the very definition of sanctimonious. Second, I often note this strange sameness to the depiction of clinical care. It goes something like this:

- A patient is [choose one or more of the following] doing poorly/unhappy with their care/suffering from a mysterious illness/critically ill/dismissed as a hypochondriac/tired of seeing so many doctors/ready to give up.

- Everyone else in the medical profession is messing up.

- Doctor author comes in and saves the day.

Atul Gawande, a staff writer at the New Yorker, is a wonderful exception to the rule that doctor writers are big show-offs.

He also happens to be a general surgeon at the Brigham, hence the “Brush with Greatness” claim in the title — I get to see him periodically on the inpatient wards.

I’m thinking of him because he wrote a fascinating piece in this week’s New Yorker on how hospitals could learn a thing or two from the Cheesecake Factory, of all places. (Note it’s not an Olive Garden — phew.) The major point is that there’s potentially real value in standardization — better care, lower costs — but that it won’t be easy for individualist doctors and isolated health care systems to adapt.

As usual in one of Atul’s pieces, the tone is just right. It’s been a revelation to read a doctor who writes about clinical medicine in a style that 1) avoids sanctimony and, 2) does not feature a “saved-the-day” story starring MD Superstar.

In fact, when Atul does involve himself in his pieces, it’s usually either as interested observer (such as this wonderful and truly heartbreaking description of modern aging), or to describe his own failings as an MD — trouble with an operation, an erroneous diagnosis, a sense of feeling overwhelmed. These disclosures are inevitably followed by reflections on how he might improve — how very human and appealing.

My favorite part of the current New Yorker piece juxtaposes the precision and lack of waste on the food prep lines of the restaurant with the chaos of a brief hospitalization for an elderly woman after a fall. The woman, who has Alzheimer’s, is the mother of the Regional Manager of the Cheesecake Factory branches here in Boston:

The doctors ordered a series of tests and scans, and kept her overnight. They never figured out what the problem was. Luz [the Regional Manager] understood that sometimes explanations prove elusive. But the clinicians didn’t seem to be following any coordinated plan of action. The emergency doctor told the family one plan, the admitting internist described another, and the consulting specialist a third. Thousands of dollars had been spent on tests, but nobody ever told Luz the results….

Luz’s family seemed to encounter this kind of disorganization, imprecision, and waste wherever his mother went for help. “It is unbelievable to me that they would not manage this better,” Luz said.

If you do any inpatient medicine at all, this is all too recognizable a scenario, and frankly quite painful. And, as usual in Atul’s pieces, a real motivator for us to get better at what we do.

Hey, that would make a good name for a book!

August 13th, 2012

A Poll: Clintons vs Bush

Got this email recently from a former colleague who now does mostly international work:

Hey Paul — nice recap of the IAC conference. But I was wondering if you’d forgotten about someone very important when you wrote, “I can’t think of any major politicians who have done more for HIV than the Clintons.”

Um, how about George W. Bush?

Thanks for considering,

John

It’s a fair point, and I confess I didn’t think of Bush when I wrote that sentence — but should have. The impact of PEPFAR has been absolutely huge (recent summary here), and I’m nearly 100% sure when the history books are written about Bush II’s presidency, this will stand as his greatest accomplishment.

(But then I would think that.)

Meanwhile, the Clinton Foundation and Hillary’s advocacy for HIV patients while Secretary of State are also very impressive.

So what’s your view?