An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

October 8th, 2024

Why We Have Antibiotic Shortages and Price Hikes — And What One Very Enterprising Doctor Did in Response

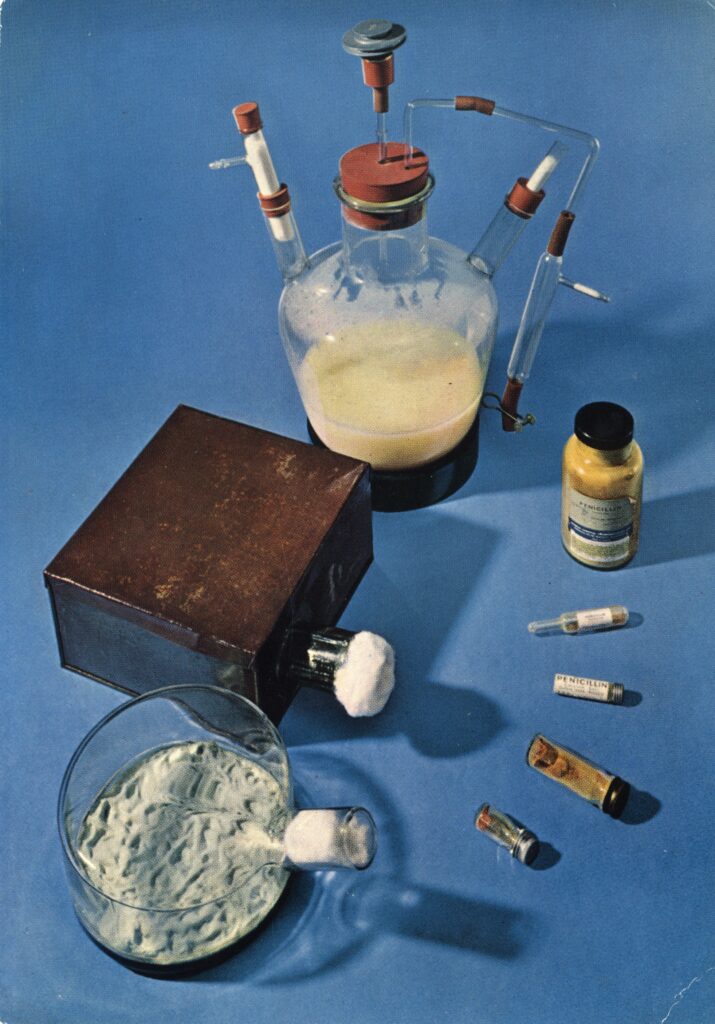

Early penicillin apparatus (National Library of Medicine)

At the start of our weekly case conference, we get announcements from one of our ID pharmacists. New drug approvals, hospital policies, updated guidelines — that kind of thing. But over the last decade or so, the most common topic they’ll comment on is the latest important antibiotic shortage.

For those not in medicine, you might think these shortages would involve cutting-edge compounds that have complex manufacturing or distribution challenges. On the contrary! These are rarely fancy, high-tech drugs. They’re much more commonly generics that have been available for literally decades — isoniazid, amoxicillin, intravenous acyclovir, and injectable benzathine penicillin. All have important recent drug shortage in the United States that impacted patient care.

If you’ve ever wondered why these shortages exist, an authoritative review has just appeared in Clinical Infectious Diseases outlining the problems clearly. In essence, drug production internationally is much cheaper, and these lower priced versions make it all but impossible for US manufacturers to turn a profit on generic drugs. In addition, the FDA lacks the resources to provide sufficient quality oversight of the drugs made overseas. The result?

This combination of fierce price competition from Asian markets and irregular quality oversight by the FDA in these regions has resulted in a high prevalence of chronic shortages of generic drugs, with US drug shortages at a ten-year high and antimicrobials being 42% more likely to experience a drug shortage than other drug classes. As of May 31, 2024, 37 antimicrobials were listed in shortage with shortages of antimicrobial agents ranking second among all pharmaceutical classes.

Drug shortages can also lead to substantial price increases, especially when a single company remains the sole manufacturer of an essential drug. The recommended treatment of syphilis, benzathine penicillin (shortage first reported last summer), is one striking example. As a long-acting injectable drug, benzathine penicillin requires rigorous and sterile manufacturing facilities and careful oversight. Given the inexpensive price worldwide and low profit margins, there is little incentive for any company to take on making and licensing this critical drug. The number of US manufactures of benzathine penicillin can now be counted on one finger.

What remains is the perfect formula for a price increase:

- One US manufacturer — no price competition

- Barriers and few incentives for other companies to enter the market

- An increased demand due to increased incidence of syphilis

- Lack of proven alternatives, especially in certain clinical settings, most notably pregnancy

The result? A price increase! No advanced degree in economics needed! The price of a single dose of benzathine penicillin is now over $600! I’ve heard some pharmacies charge nearly $1000. Wow.

Even worse, many of the people diagnosed with syphilis have inadequate insurance coverage, in particular pregnant women. If untreated, they can pass the infection to their babies in a disastrous scenario that is 100% preventable with adequate treatment. As demonstrated in this recent review of cases of congenital syphilis in Missouri, the incidence of these cases is strongly associated with adverse social determinants of health, including absent prenatal care, substance use disorder, and housing instability.

Enter Dr. Eamonn Vitt, solo practitioner in lower Manhattan, and former punk rocker and Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) veteran. He eagerly admits he was inspired by the business practices of the legendary band Fugazi, who refused to sign to or work with corporate record labels so they could maintain total control over their music. So when I say he’s a solo practitioner, I really mean it. You know those primary care practices now owned by giant insurance companies, healthcare systems, or private equity? The opposite of that. From his practice web site:

We work for you – not the shareholders of the health insurance corporations. We are out-of-network with them. We do not take money from drug companies. We are liberated from the perverse incentives plaguing the healthcare industry. Our practice serves people from all walks of life. The fees are fair and affordable.

He runs an extremely low overhead operation — just him, one assistant, an office, and a refrigerator full of vaccines he has on hand for his patient clientele, which consists of a large number of gay men who have sought him out for HIV care or for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Not surprisingly given his patient panel, Eamonn has to treat STIs frequently, and this means prescribing benzathine penicillin for syphilis. As he told me in a recent IDSA podcast, his patients take his prescription for penicillin down to the pharmacy, and have been increasingly met with a big price shock.

I have amazing patients, super smart people, and they have very well developed BS detectors and they all are unhappy with this. I have an economically diverse practice. I have patients who work in fast food, and I have doctors and lawyers. No one wants to pay $500 … We learn when we’re 11, that monopolies are bad for the consumer, and it’s probably one of the few bipartisan things in the country that both the red team and the blue team agree on, that monopolies are bad.

So how did he solve the problem for his patients? In a fascinating, tangled tale that involved the perfect mix of his activism, painstaking research, and energetic sleuthing, along with important supporting roles played by the FDA, Doctors without Borders, and the on-line pharmacy CostPlus Drugs, Eamonn now gets the drug for $30 a dose.

(TL/DR for those not interested in listening to podcasts: he found out the drug could be imported under an FDA emergency action, researched the cost paid by his MSF former colleagues, and cold emailed Mark Cuban — who, amazingly, responded to his email!)

Eamonn office refrigerator is a bit more crowded, now with doses of benzathine penicillin, but I’m sure his patients are incredibly grateful.

I’d wrap up by posting a video of Fugazi, but they’re a bit too hardcore for me. Instead, here’s a favorite of mine from an earlier punk era.

(h/t Dr. Katerina Christopoulos for connecting me to Eamonn, and to him for sharing this story.)

September 19th, 2024

How Electronic Health Records Tyrannize Doctors — ID Doctors in Particular

A paper just appeared in the Journal of General Internal Medicine entitled “National Comparison of Ambulatory Physician Electronic Health Record Use Across Specialties.” The goal of the study was to track clinician workload by specialty, divided into various functions — documentation, chart review, orders, inbox.

Importantly, there was no gaming the system. By using Epic’s built-in function, they tracked “active” EHR time (any mouse activity or keystrokes) using a 5-second inactivity timeout. They additionally measured time spent on the EHR outside of scheduled hours on days with scheduled appointments, and time on unscheduled days.

Remember, some of this is time working on notes, follow-ups, and inbox wasn’t possible in the days of paper charts. Easy access to patient records for clinicians is mostly a good thing, but it has brought with it several untoward consequences, with longer hours of EHR use associated with physician burnout.

The results? Here’s the figure, reproduced with the kind permission of the lead author:

Gosh, does this ring true. Hey, I’m logged into Epic right now as I write this, and it’s 5:42 a.m. on a Wednesday, reviewing patient and clinician messages, test results, and — most importantly — prepping for the clinic session I have this afternoon and peeking ahead to tomorrow morning’s appointments, reading through charts to be ready for the visits.

Now none of this is unique to ID docs. I’m married to a primary care pediatrician, and her inbox activity easily exceeds mine. But here are several reasons why ID doctors finished #1 in this review, at least based on my highly anecdotal and admittedly biased perspective.

- Chart review. Before, during, and after a visit. It’s so critical. It would be impossible to do this work without meticulous attention to the history and results. You know that Media tab in Epic, the one you’d like to ignore? That place where “information goes to die”? We ID docs dive right in, painful as opening those scanned documents and inscrutable PDFs might be. If we see someone is scheduled to see us and we don’t have the records to review ahead of time, this elicits deep anxiety and an all-out effort to remedy the situation ASAP. Code Chart.

- Notes. The other day, we hosted some medical students for dinner at our house, and a (quite brilliant) future surgeon recounted something she learned on a recent Transplant Surgery rotation: “Just read the ID notes,” she said. “My resident said you can get rid of the rest of the chart documentation and find a complete and accurate summary of even the most complicated cases.” Indeed. These works of art take time.

- Complexity. People don’t refer to or consult ID for routine issues in Infectious Diseases — they manage them on their own. That community-acquired pneumonia responding to empiric antibiotics? That outpatient with a UTI getting better on nitrofurantoin? That drained abscess, now healing on cephalexin and local care? It’s the opposite of those cases that make up the daily ID doctor’s work — the diagnostic dilemma, the failure to respond, the highly resistant or confusing microbiology. Tough stuff all of them, and I’ve been at this a while.

- OCD. To varying degrees, all us ID doctors suffer from obsessive-compulsive disorder. I’ll confess — the struggle is fierce. If you have never written a note that starts out, “Briefly, …” and is then followed by a scree of prose longer than any other note in the chart, the Infectious Diseases Society of America deserves the right to wonder about your ID credentials.

- Breadth. If there’s a medical or surgical service out there that hasn’t had a patient with an ID complication or issue, I haven’t heard of it. From the broadest primary care clinicians to the super-specialized surgeons who only manage one component of a given body part, we’ve seen patients from them all. This creates quite the pressure to review records and do some pre-visit research about the latest obscure medical treatments or surgical techniques.

All of this requires a lot of EHR chart use, and time spent outside of clinical hours finishing up the work. Look at the distribution of activities in the figure — it shows it’s not just one thing we’re doing more than others. It’s the entire bundle, the results of an extremely diversified portfolio of clicks, keystrokes, and scrolling.

Some might argue that ID doctors should just write shorter notes, and I agree. Notes really should focus on our interpretation of what has happened, why we think it’s going on, and what we recommend — not just a re-statement of material that’s already available elsewhere, if others took the time to look at it.

But importantly, writing shorter notes is easier said than done. Many of my colleagues tell me that if they don’t write out the details of the history, or re-type all the results, they don’t really learn the full story, analogous to taking notes during an important lecture. Others cite the positive feedback they receive from others (see #2 in the above list), saying they don’t want to disappoint their non-ID consulters.

But here’s another motivator to stop providing this chronicling service. We non-procedural specialists consistently find ourselves at the low end of the payment scale for MDs, a situation that will never change with Relative Value Units (RVUs) providing the metric for determining salaries. Sadly, the recent trend wasn’t encouraging — our latest reported salaries were lower than the previous year.

And, as noted in this compelling post, I doubt anyone is getting paid for time spent on the EHR outside of work hours.

Or getting paid by the word.

September 6th, 2024

Five Reflections after Attending on General Medicine This Year

Acronyms on the medicine service remain mystifying.

Here are five things that occurred to me after a stint on General Medicine this year, where (per our department’s wise policy), I was paired with an experienced and excellent hospitalist to oversee two medical residents, three interns, and two medical students.

#1: Energy. Medical house officers radiate positive energy. Yes, it was summertime, and motivations were high to tackle their new responsibilities (leading teams for the PGY-2s, being a real doctor for the PGY-1s).

But at any time of year, this energy is a wonderful thing to experience. You can’t help but be caught up in the spirit — their desires to help their patients, to learn, and to teach influence us all. The positive effect it had on our medical students was especially notable. Makes a person hopeful for the future of medicine in this country. Yay!

#2: Acronyms rule. One of the hardest things for me as a trainee was deciphering the blizzard of letters sprayed around during morning rounds and in patients’ charts. I get flashbacks to this mystification each time I attend on medicine, and am not shy about asking for a glossary.

This year’s most prominent newcomer was GDMT — guideline-directed medical therapy — in which patients with heart failure receive a quartet of medications, each of which improved outcomes in comparative clinical trials. While I knew about these drugs and their favorable studies, the acronym for all of them as a group was new to me.

But now that I know about GDMT, label me as skeptical as this general internist. Sure, it could work for some eventually to get started on an angiotensin receptor inhibitor, a beta blocker, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, and a SGLT2 inhibitor. But during the first few days of hospitalization? It seems like too much too soon.

#3: Fear of quinolones is now mainstream medical knowledge. I totally get it — these are drugs that have unexpected and sometimes severe toxicities. Permit me to bring out this incredible graphic, kindly shared with me years ago, highlighting the various problems:

But the FDA warning to avoid these drugs in outpatients has so permeated clinical practice that they are now frequently overlooked even when a quinolone is the best treatment option. So here’s a reminder that they are highly effective, have excellent oral bioavailability, and are usually quite safe.

Hey, I get the irony. Here I am, an ID doctor pitching for quinolones in 2024, while if we go back a couple of decades we could easily have called them the most overused antibiotic drug class by medical services — so much so that I used to use this slide as a joke!

That is a completely made-up rule.

Still funny? You be the judge.

#4: We ID doctors offer something special when we attend on general medicine. Well, what do you expect me to say? I’ve argued for self-selected subspecialists to do inpatient general medicine before, but now there’s something new that occurred to me this time about ID in particular. Namely, we’re among the remaining few doctors who can see a problem in a hospitalized patient on the general medical service, act as the primary attending of record, and then arrange to see that patient after discharge in our clinic for follow-up.

Not all of us, of course — some ID doctors don’t do outpatient care — and yes, there are other subspecialists who do this as well. But at least at our institution, we seem to be the leaders in this particular flexibility, one that is especially important since the number of general internists who do both outpatient and inpatient care seems to shrink yearly.

#5: Hyponatremia continues to perplex. Way back in the early days of UpToDate, the visionary founder Dr. Burton (Bud) Rose shared with me that hyponatremia was the most common single topic looked up on his nascent clinical information resource. I wouldn’t be surprised if this is still the case — causes, evaluation, management, all still a challenge! So many discussions on rounds focused on the results of the daily sodium, the volume assessment, the urine electrolytes, the best approach to correct the low sodium, and how fast to do so.

Here’s a “big picture” view from one ID doc (me):

- People sick enough to be hospitalized often have low sodium.

- There are many possible causes, and they’re not mutually exclusive. Often more than one is in play.

- If the underlying process (pneumonia, CNS disease, CHF, GI bleeding, whatever) is treated, and/or the offending drug stopped, in most cases a small degree of volume restriction (if volume replete) or hydration (if volume deplete) will lead to a slow correction.

- In more severe cases, get help from your friendly nephrologist.

That’s my five! And thanks again to the terrific medical team for making the experience so rewarding.

August 19th, 2024

More on Munich and the 25th Annual International AIDS Conference

Longtime readers may note the absence of this year’s Really Rapid Review™ (RRR) of the latest big HIV conference, the one that just happened in Munich. These RRR posts have been a regular on this site for a gazillion years, give or take a few, with a brief break during the peak of the pandemic.

My excuse this time? Pretty mundane, I’m afraid. Due to some additional obligations, deadlines, and other matters, I simply never got around to it. And of course if I write it now, more than 2 weeks after the conference has ended, it would classify solely as a Review, not meeting the validated criteria for being a Really Rapid one. Oh well.

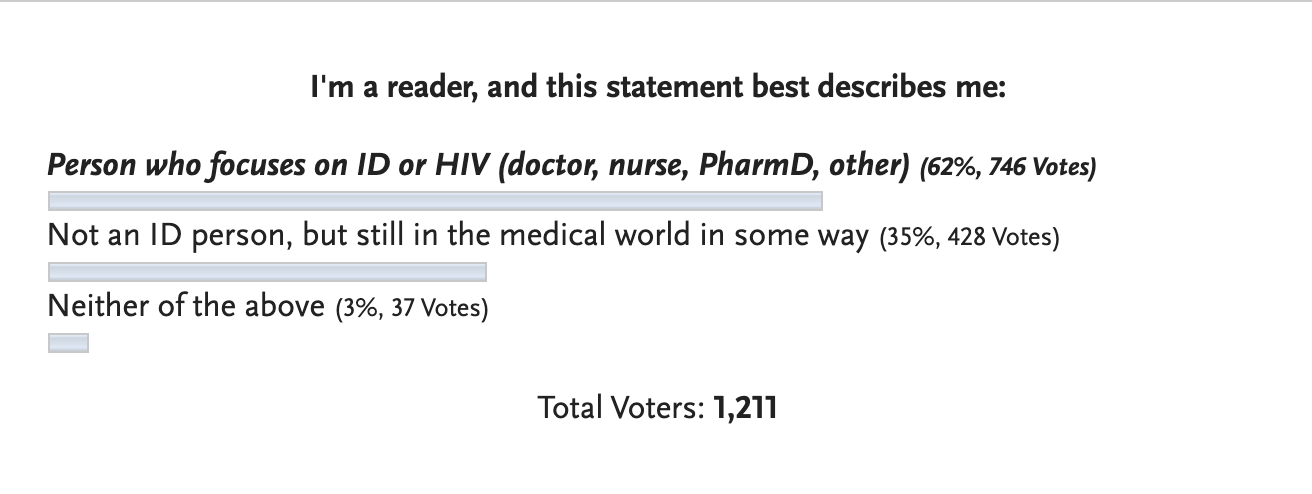

For just under 40% of you, however, you might not even notice. The evidence? Here’s the results of the poll on who you are — many thanks for voting!

Not-so-bold statement — for most of the non-ID readers, the RRR posts probably aren’t your cup of tea anyway. For each conference summary, you probably scrolled to the bottom for the funny video*, or just skipped the post entirely.

(*Important note — there are some funny videos at the end of this post.)

The results of this poll were a pleasant surprise, as one of my goals in writing has always been to appeal to a broader audience, even if the core of what I write about is my specialty, Infectious Diseases. Let’s face it, the community of ID specialists is small, in inverse proportion to the number of microbes, antimicrobials, and taxonomic changes over the years for various fungi*.

(*Total inside joke, that last one, about the fungi. Candida krusei is now Pichia kudriavzevii? C’mon, give me a break.)

As a compensation to our ID readers, I offer instead something I hope you’ll find of interest, which is a video of a Munich conference summary I did with one of the leaders in the HIV field, Dr. Laura Waters. She covered the HIV treatment studies; the prevention and non-ART complications went to me. But we both chimed in frequently on each other’s presentations, with lots of active discussion.

Plus, if you don’t know about Laura, you certainly should — she’s a GU/HIV consultant and the HIV Lead at the Mortimer Market Centre in London, and the former chair of the British HIV Association (BHIVA), among other achievements.

She’s also an insightful analyst of HIV clinical research, a go-to person to give a skilled and often trenchant interpretation of a study’s design, analysis, and conclusions. If you’re wondering who that intelligent and funny person is with the English accent who pops up first to the conference microphone after a study presentation — the person asking the best question — let me introduce you to Dr. Laura Waters.

(She even has a Wikipedia page! Impressed.)

Anyway, here’s the video. Enjoy!

Before I entirely leave Munich, however, I want to share a brilliant insight about travel and hotel rooms made by tech person and writer Trung Phan (who likely is making his first appearance on an Infectious Diseases blog).

It’s about the showers — yes, the showers. In a section of a post entitled, Hotel Showers Are Insane, he writes:

The thing about old hotels is that they need to be renovated. My amateur analysis is that it’s possible to renovate most older structures and maintain the charm of the original facade…except the bathroom. Updating the toilet and shower to modern standards often involves making it look modern and, therefore, a bit out of place.

This is all fine except for the fact that hotel showers have turned into SAT exams. We stayed at 8 hotels on the trip and every single one had a different and confusing knob/heat/spray setting (half of them had to include instructions) …When you need a shower instruction manual, it is time to go back to the drawing board.

Let the record show that while Munich is a beautiful, vibrant city with a great public transit system, historic sites, river surfing, and wonderful restaurants, the shower in my hotel room was every bit as inscrutable as the description above. I’m still convinced I never mastered its numerous byzantine settings.

If you add that many hotel showers in Europe have no full door or shower curtain — or strangely, no water barrier at all — these showers present a mystifying challenge that defies full explanation.

So agree, Trung — they are insane.

July 25th, 2024

Lenacapavir PrEP Trial Brings Down the House at the International AIDS Conference

Yesterday, at the 2024 AIDS Conference in Munich, we experienced one of those thrilling moments you always hope for when attending a scientific conference.

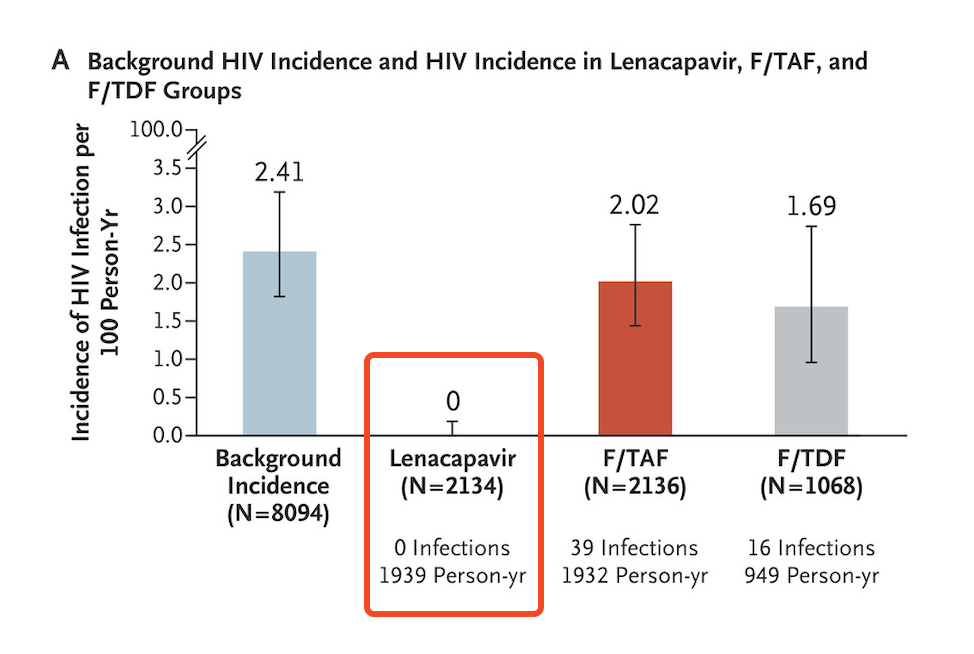

Dr. Linda-Gail Bekker, speaking on behalf of the study investigators, presented the data on the PURPOSE-1 study of HIV prevention using twice-yearly injectable lenacapavir; results were simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The results originally made headlines when the study was halted by the external independent data monitoring committee in June — some examples:

Twice-yearly Injection Fully Protects Women from HIV

New Drug Provides Total Protection From HIV in Trial of Young African Women

Lencapavir Shows 100% Efficacy and Zero Infections in HIV Prevention

Beginning of End of HIV Epidemic?

Certainly, all of us at the conference knew the results before yesterday’s presentation of the data. Regardless, when the results slide flashed on the screen, highlighting zero infections in the lenacapavir arm, there was spontaneous applause from the thousands assembled in the cavernous convention center:

How could we help ourselves? Several attendees today reported to me they had tears of joy. At the end of the presentation, there was a standing ovation — one given not just to Linda-Gail for her excellent summary, but also to the other study investigators, the participants, the sponsor, and the scientists who have made so much progress in HIV prevention that we can only rejoice.

There’s a lot to commend about this clinical trial, it’s hard to know where to begin, but here’s a partial list:

- The investigators carefully engaged with the community at risk while designing the study.

- It was conducted in sites known to have a high incidence of HIV in young women, then enrolled those at highest risk (over 20% had an active STI at enrollment).

- They used a novel approach to estimating background incidence, relying on those who failed screening due to already having HIV, then applying “recency” assays to estimate the timing of when these infections occurred. It’s a complex calculation, but it avoids having a placebo arm, which of course would be unethical.

- The study was blinded, strengthening the conclusions from the data.

- The primary and secondary end points were of great interest. Note that in addition to lenacapavir being superior to both no PrEP (background incidence) and TDF/FTC, the study also showed that TAF/FTC and TDF/FTC were not meaningfully different and that TAF/FTC only provided protection with good adherence — which was unfortunately not common among those assigned to oral therapy. (The efficacy of TDF/FTC was not a defined endpoint.)

- Participants who became pregnant or were breast-feeding could continue the study with outcomes incorporated into the protocol. Such end points are critical for this study population, but too rarely assessed.

A second study in a different at-risk group (predominantly MSM) is ongoing, PURPOSE-2, with results expected within the next 6 months or so. If it has comparably favorable results, at that point the company can file for regulatory approval, which presumably will be swift.

Then, as noted in the accompanying editorial in NEJM, other challenges loom — implementation, access and cost. These are challenges everywhere, not just in Africa where the study was conducted.

Indeed, we know how difficult injectable PrEP is to start in our clinics, even though cabotegravir gained FDA approval for this indication by being superior to oral TDF/FTC in two excellent clinical trials (HPTN 083 and 084). In fact, the 084 study of injectable cabotegravir given every two months demonstrated a similar 100% protection from HIV among the women adherent to the injection schedule.

Despite these favorable results, and patient interest in injectable PrEP, someone told me that less than 5% of PrEP in the United States is now with cabotegravir. The primary reasons for underutilization relate to strained clinic resources (someone has to give the injections), cost, drug access, and manufacturing.

Still — zero infections PURPOSE-1. Wow. If you are running a clinical trial, you dream about getting results like this.

Let’s join the applause.

July 14th, 2024

Should We Continue to Use Contact Precautions for Patients with MRSA?

The stalking MRSA monster, circa the year 2000.

Back in the early 2000s, I heard about a local hospital that eliminated contact precautions while caring for patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). No more required gowns and gloves, or warning signs on the doors, or private rooms for patients known to have MRSA. They planned to track MRSA cases carefully over the next 2 years, and then decide, based on these results, whether the contact precautions should be resumed.

Alas, cases of MRSA increased — increased a lot. Back came the gowns, the infection control signs, and the general hassle.

Of course we know now, looking back, that this had nothing to do with their policy change. Their mistake was not appreciating that the community epidemiology would override anything they were doing within their walls.

The rising incidence of MRSA starting around 2000 was a universal phenomenon during that period, at least here in the United States. It happened in every clinical setting and every region — inpatient, outpatient, long-term care facilities, emergency rooms, urgent care centers, intensive care units, you name it. I remember telling our head of infection control back then that I wouldn’t be surprised if one day we’d look back on methicillin-sensitive staph (MSSA) with as much nostalgia as we do the penicillin-sensitive strains from the pre-antibiotic era. MRSA would become that dominant.

For the record, that was one of the wrongest predictions I’ve ever made — right up there with my lack of appreciation of the show Friends (“too cliched, will never catch on” after briefly watching one episode), and my stance that football will eventually no longer be America’s favorite sport (“parents won’t want their kids to play, too dangerous — it will become like boxing”).

So how wrong was I about the future of MRSA? Rates stopped increasing in the mid 2000s, and have been gradually declining ever since — and no one knows precisely why. In a large VA study, MRSA accounted for 39% of Staph aureus isolates in 2019, down from 54% in 2010.

(I have still never watched a full episode of Friends. And I’m also hoping that one day, my prediction about football comes true.)

I bring up this up now because many hospitals (including ours) still have contact precautions for MRSA, a policy we share with roughly two-thirds of U.S. hospitals, and by some guidelines is considered “essential”. Bright yellow disposable gowns replaced the cloth ones we once sent to the laundry; there are stacks of gowns and boxes of gloves sitting right outside the rooms of all patients with MRSA (even asymptomatic colonization), and there are precaution signs on the doors.

But there’s still a viable escape route for this policy. Another teaching hospital right across the street stopped MRSA contact precautions years ago. Several other Boston and New England hospitals have done the same. Instead, they’ve redoubled their efforts in the importance of hand hygiene, to the benefit of all. Communicating with their infection control directors, I’ve learned that nothing has changed in their MRSA incidence. And, dear readers, rest assured, it’s not as if those hospitals’ MRSA strains — one is literally a single block away! — are any different from ours.

What’s driving these starkly divergent approaches? To answer this question, it’s helpful to look at the evidence motivating the differences. Such a review is expertly outlined by Dr. Daniel Diekema and colleagues in a viewpoint entitled, “Are Contact Precautions ‘Essential’ for the Prevention of Healthcare-associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus?” They summarize the studies looking at the effectiveness of this approach in reducing within-hospital transmission of this pesky bug, and find that the data are far from clear. Indeed, this is one of those murky areas in clinical practice where anyone could cherry pick a study to support whatever view they held to begin with.

On the other hand, how about the potential harms and costs? These are easier to outline, so let me count the ways, with an obvious half-dozen:

1. Patient care. I’d argue they’re called “barrier” precautions for two reasons — both the obvious barrier the gown put between you and the patient, and the psychological barrier it puts on clinicians before going in the room and seeing the patient. In short, patients on MRSA precautions are seen and examined less often than those not on precautions. Anyone who does hospital-based care will confirm this obvious fact.

2. Patient satisfaction. While a fraction of patients might prefer that providers don gowns and gloves before entering the room, it’s been my experience that a majority don’t like the stigma associated with the label. They fear for their family and friends who visit, who usually do not wear the gowns or gloves. They’re thrilled if we can clear them from MRSA precautions, though this process is cumbersome and inefficient, especially when they’re outpatients.

3. Cost. No surprise, it costs money to send cloth gowns out to institutional laundry services; same story for purchasing and disposing of the paper ones.

4. Environmental impact. I’ve heard the disposable gowns are net neutral in environmental impact compared to washable gowns; confess I haven’t looked into this carefully. But neither type of gown can be good, right? And is there anything more “universal” in the MRSA precautions rooms than the overstuffed bins with these bulky gowns? What an awful look.

5. Bed management. Covid-19 disrupted so much of our healthcare system that it’s hard to choose a single thing it changed the most, but one of the candidates is the broad category sometimes labeled “patient disposition.” In short, essentially every hospital is dealing with overflowing emergency rooms, record-high hospital census and emergency room borders, and difficulty finding places for patients to go. (For a memorable personal account from a local journalist, read about her experience with the current state of affairs.) MRSA precautions in those institutions that still have shared patient rooms only further slow down the process of finding the right bed for the right patient.

6. Illogical inconsistencies in the policy. I could choose many, but let me highlight one: Inpatient care for those with MRSA means gowns, gloves, and precaution signs; outpatient care, we rarely do any of the above, even if the clinician doing the outpatient care later that day will move to the inpatient setting. What’s up with that? If you’ll excuse the baseball metaphor, it reminds me of the designated hitter rule that for decades applied only to the American League. It never made sense to me that we had to endure the clueless pitcher at bat in the National League, leading to all but an automatic out. Baseball eventually came to its senses, instituting the designated hitter rule in both leagues starting in 2020.

I reached out to Dan and to senior author Dr. Daniel Morgan before posting this piece, and the latter reminded me of a planned cluster randomized clinical trial which we hope will give more definitive evidence about whether this practice is worth continuing. Here’s hoping the study gives us solid data one way or another.

In the meantime, like other medical interventions that should only be instituted if the benefits clearly outweigh the risks, costs, and hassle, I’d argue strongly that a policy of contact precautions for MRSA no longer meets these criteria.

And by the way, nobody misses those lame pitcher at bats now that the designated hitter is universal.

June 20th, 2024

Early Heatwave ID Link-o-Rama

We’ll get to the links in a moment, but first, a little poll. You might have heard that there’s a new Editor-in-Chief at NEJM Journal Watch, Dr. Raja-Elie Abdulnour. We met recently, and discussed this column or blog or newsletter or whatever you want to call it.

A topic came up that we’ve been wondering about for a while — who are you, the readers of this thing? If you could take a moment to vote, I’d very much appreciate it.

Feel free to elaborate further in the comments. I promise that no one will follow up asking you to explain how to determine the length of antibiotic therapy, why learning the names of HIV drugs is so difficult, or the reason why medical students know more about listeria than any other bacterial infection.

On to the links we go!

In a randomized clinical trial of pre-exposure prophylaxis for prevention of HIV in women, twice-yearly injectable lenacapavir was superior to the oral options TDF/FTC (Truvada) or TAF/FTC (Descovy). None — that’s right ZERO! — of the 2134 women who received lenacapavir contracted HIV, versus 16 of 1068 on TDF/FTC, and 39 of 2136 on TAF/FTC. Study was conducted in 25 sites in South Africa and in Uganda. Many more details on this important study undoubtedly to come at this summer’s AIDS 2024 conference in Munich, but based on these results alone, it’s a major advance in HIV prevention strategies.

In antibiotic treatment of sepsis, continuous versus intermittent β-lactam antibiotic infusions did not significantly reduce 90-day mortality. The study, cleverly called BLING III (“Beta-Lactam Infusion Group”), promises to generate lots of controversy, as there was an observed benefit — just not enough to be statistically significant for the primary endpoint. Another way of looking at it is that there could be benefit for this critically ill population. Suspect many will continue to use continuous infusion therapy unless there’s shown to be some harm.

Compared to vancomycin plus cefepime, a cohort study showed an association between use of vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam and increased mortality. The study design took advantage of a “natural experiment,” one driven by a shortage of the pip-tazo. The leading hypothesis for the results is that the extra anaerobic coverage of pip-tazo is harmful. Alternatively, perhaps this is just an association due to the different time periods, with actual no causation — remember, the randomized ACORN trial showed no difference in major clinical outcomes between pip-tazo and cefepime as empiric therapy.

In a prospective analysis of a large patient population switching to tenofovir/lamivudine/dolutegravir (TLD), virologic failure with resistance occurred, but was rare. Switching to this regimen while viremic was a risk factor. With over 20 million people on this treatment globally, ongoing monitoring for emergent integrase inhibitor resistance will be critical — as will transmitted resistance, as the default first-line and second-line therapy in most of the world is now TLD.

Brief aside — I learned recently from my brilliant colleague Dr. Emily Hyle that a month of TLD now costs around $3 in Africa, while a resistance genotype is still $300! In an era where another molecular test, the GeneXpert for TB, is widely available in this region, this high price of HIV resistance testing is an absurdity that must end soon.

Is there a role for two-drug HIV therapy in Africa? From a medical perspective, the answer to this question is of course there is — there’s a role for such treatment now in the developed world, with dolutegravir/lamivudine and long-acting injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine being the most important options. But availability of lab testing is a major barrier, with limited access to renal monitoring, assessment of hepatitis B status, and the already called-out HIV resistance testing. Not so bold prediction: In the not-so-distant future, we will be hearing a lot about tenofovir DF complications (renal, bone disease) in older PWH globally, especially those with comorbidities.

Pivmecillinam is now FDA-approved for treatment of uncomplicated UTIs in the United States. In case you’re surprised at the development of this “new” antibiotic for this indication (raises hand!), there’s a reason I put new in quotes — it’s been available in other countries for decades. Despite broad use in some European countries, this review found resistance to be uncommon. I’ve been told by one of our ID pharmacists that it won’t be available in our pharmacies here in the USA until 2025.

An insider monkey.

The metropolitan area in the United States with the highest HIV rate is in southern Florida, the Miami-Fort Lauderdale area. Caveat — this list is from a link found on Yahoo Finance called Insider Monkey, and though they used CDC data, I didn’t check their methodology. But the results show no major surprises — most of the top cities are either in the South, or the big metropolitan areas in the Northeast (south of New England) and California.

Patients who had de-escalation of broad-spectrum beta-lactam therapy experienced a reduced risk for emergent gram-negative infections compared to those who did not. While the results could be confounded by baseline differences in patient characteristics, this result makes abundant sense. In other words, let’s change that meropenem to ceftriaxone when we can!

In a prospective study of healthcare workers who did not respond to hepatitis B vaccination, two doses of the adjuvanted hepatitis B vaccine elicited serologic responses in 91%. Participants had to have non-response to five doses of the standard vaccine, hence these are impressive results. Though not a comparative clinical trial, how long before this vaccine is the default recommended strategy for this population at high-risk for occupational exposure?

A detailed virologic study of 563 HIV isolates from blood donors from 2015–2020 found PI, NRTI, and NNRTI resistance mutations in 5.0%, 4.6% and 13.9% of sequenced samples. The overwhelming majority (96%) were subtype B. Resistance declined over time. Two samples (0.4%) had the M184V mutation, including one that also had K65R — perhaps in a person who had taken PrEP? Unfortunately, no sequencing of integrase inhibitor mutations was performed.

Here are some ID-related “therapeutic myths” in solid-organ transplantation. Highlights include treatment of all asymptomatic bacteriuria after kidney transplant (don’t), giving antibiotic prophylaxis for dental work (don’t again), and the lack of evidence for vaccinations inducing rejection. Good graphic summary.

The FDA advised companies to update the COVID vaccines to target the KP.2 strain. This is a descendent of the JN.1 variant that circulated widely this past winter. COVID cases will inevitably increase this respiratory virus season (mid-late November is when it typically kicks into high gear), so having an updated vaccine for people at high risk for complications is a good idea. The question remains whether all previously immunized and infected people need annual boosters — hope one day we get a good trial to answer that question.

Believe it or not, there’s another pneumococcal vaccine coming. This version covers 21 serotypes, just 1 more numerically than the PCV-20. However, the serotypes are different, including 8 not covered by other currently available pneumococcal vaccines. The manufacturer has data that these serotypes more closely match the disease-causing strains in adults. On June 27, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will meet to review how it should fit in with currently available options.

Staph aureus susceptibilities over a 10-year period showed a rising rate of resistance to tetracyclines and trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole, especially in MRSA strains. The study included 382 149 isolates from 2010–2019, stratified by MRSA versus non-MRSA. Among MRSA strains, tetracycline resistance increased from 3.6% in 2010 to 12.8% in 2019; for TMP-SMX, it increased from 2.6% to 9.2%. The good news? The proportion overall that were MRSA declined from 53.6% in 2010 to 38.8%, a favorable (and mysterious) trend seen previously in other studies that no one has been able to explain.

A review of over 60,000 inpatient ID consults at an academic medical center from 2014–2023 found a high proportion were done on patients with terminal or incurable illness, with a 7.5% mortality during the admission. There were two striking findings in this study. First, the obvious one, which is that people who need ID consults are really sick. Second, the volume of ID consults has nearly doubled over the past decade — from 5.0/100 to 9.9/100 patients. If you think you’ve been increasingly busy on your inpatient consult service, this is no illusion.

In a randomized clinical trial, povidone iodine in alcohol was noninferior to chlorhexidine gluconate in alcohol to prevent infection after cardiac or abdominal surgery. The importance of the study is the much-lower cost of the povidine iodine, and chlorhexidine is therefore much less widely available globally. Hey, I believe this is the first time I’ve covered a topical antimicrobial study in a Link-o-Rama!

Before we wrap up, first, don’t forget to take the poll (see above); and second, a little childhood history for those of a certain age (mine, or a bit older).

In the 1960s, I learned there was an important debate about the best baseball player in the world, Willie Mays or Mickey Mantle. Increasingly obsessed with this sport to the point that I bored my parents senseless with my endless ruminations on this and other baseball-related topics, I intensively studied biographies and statistics of these two players, wanting ever so much for Mickey Mantle to be the winner with a passion that makes absolutely no sense today.

Turns out, no matter how I twisted the data — focusing only on their best years, or most heroic moments, or their potential without injuries — the answer came back the same again and again.

Willie was better. Possibly best ever. Rest in peace, Say Hey Kid!

June 9th, 2024

The Mysteries and Challenges of the RPR — and a Proposed Clinical Trial

Detroit, early 20th century. RPRs are the Karius of the day.

Last week, we had a real treat for our weekly ID/HIV clinical conference — a review of controversies in the management of syphilis in adults by Dr. Khalil Ghanem, from Johns Hopkins. He’s a well-known expert in the field of sexually transmitted infections, syphilis in particular.

A highlight of the talk was his dismantling of a particularly confusing aspect of treatment monitoring, which is the serial checking of the RPR to assess the response to treatment, along with retreatment for failure to respond. An abbreviation for rapid plasma reagin, the RPR and its oscillations have vexed clinicians and their patients for decades.

How long? Well, since 1906 — 118 years ago, if his talk (and my math) are correct. To highlight how long ago this was, he showed a slide depicting what people were driving and wearing in 1906. (See photo for approximation. His slide is much funnier.) This is emphatically not a new technology. Don’t expect a high degree of accuracy from something that debuted before widespread electrification of homes in our country.

And the test is very weird. Unlike most antibody tests in infectious diseases, it measures not antibodies directed against the pathogen of interest, Treponema pallidum, but to cardiolipin-cholesterol-lecithin antigens; it’s an immunologic response triggered by the infection.

These antibodies are called “reaginic” antibodies — whatever “reaginic” means. Not surprisingly, the RPR is the quintessential non-specific diagnostic test, with tons of false positives (11% in one study), and a very well-known (and paradoxical) cause of false-negatives when the titer is particularly high, called the “prozone” phenomenon.

Which, trust me, isn’t a zone you want to be in.

To make matters more confusing, how about those units? Here’s a summary I wrote previously trying to explain how RPRs are reported, and what they mean:

When positive, RPRs are reported in dilutions — e.g., 1:4 is a one-dilution lower (and a twofold lower) titer than 1:8. Not many of our tests get reported this way (ANA comes to mind as another); in general, it’s only considered a significant change if it’s two dilutions or more — 1:16 goes down to 1:4 after treatment, for example.

So what about this fourfold change? As summarized by Dr. Ghanem, the data supporting this notion that this change is necessary for treatment success are weak indeed — in fact, the primary argument for it is that laboratory variability is a twofold change, hence you can’t say anything significant about a titer that goes from 1:16 to 1:8.

How about the view that if the titer doesn’t drop appropriately, then the patient should at the very least be retreated, with consideration of a CSF examination to diagnose occult CNS disease? Again, data are very weak to support these recommendations, even though I’ve heard some experts strongly advocate this approach.

In summary, we can legitimately question a strategy of retreatment of syphilis for “serologic non-response”. Even the STI treatment guidelines acknowledge this uncertainty.

Failure of nontreponemal test titers to decrease fourfold within 12 months after therapy for primary or secondary syphilis (inadequate serologic response) might be indicative of treatment failure … Optimal management of persons who have an inadequate serologic response after syphilis treatment is unclear.

Sounds like the perfect setting for a clinical trial. Indeed, during the question-and-answer period, Dr. Ghanem commented that he’d like to see such a study of syphilis serologic non-response with and without further treatment.

Inspired by his talk, I offer here a potential study design:

– Inclusion criteria: Asymptomatic people with treated syphilis who have serologic non-response, defined as a failure of nontreponemal test titers to decrease fourfold within 12 months after therapy

– Stratifications: Stage of disease (early vs late), HIV

– Exclusion criteria: Suspected reinfection, pregnancy, non-penicillin therapy

– Intervention: Randomization to 1) retreatment with penicillin or, 2) ongoing clinical monitoring alone, with assumption that the titer is the patient’s new baseline

– Primary endpoint: Clinical manifestations of treatment failure

– Secondary endpoints: RPR trajectory, other blood tests, additional testing (such as CSF exams), other treatments, patient satisfaction score, clinician time, costs

Would you refer a patient who meets these criteria into such a study? Anyone interested in doing it? Seems right up the alley of the great pragmatic trials run by our ID and sexual health colleagues in the United Kingdom — hope they (or someone else) will give it some thought.

And though it has nothing to do with syphilis, this UK export certainly makes me laugh every time I watch it.

(Thanks to Dr. Ghanem for sharing his expertise, and for input on this post. You can watch a version of his talk at this year’s CROI.)

May 28th, 2024

More on ID Doctors and Primary Care for People with HIV

People waiting to see their new primary care doctor.

A recently published study suggested that “non-ID doctors do better” when it comes to providing primary care to people with HIV.

At least that was the attention-grabbing subject line of an email summary distributed by a local primary care doctor, Dr. Geoffrey Modest. He periodically sends around detailed descriptions of studies he finds interesting, then posts them on his blog. Sign up, it’s great value!

But does this recent study really say that? And does it help answer the “who should do HIV primary care” debate? Let’s take a quick look at the study design and results.

Under the auspices of the CDC’s Medical Monitoring Project, 6323 adults receiving HIV care from 2019-2021 were included. The investigators selected a random group to undergo a phone or face-to-face interview. Patients from 16 states and Puerto Rico participated.

The clinical endpoints of interest as summarized in the abstract:

… retention in care; antiretroviral therapy prescription; antiretroviral therapy adherence; viral suppression; gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis testing; satisfaction with HIV care; and HIV provider trust.

Compared to the non-ID providers, the ID providers’ patients were less likely to be “retained in care” (83.1% vs 89.7%), and less likely to be screened for STIs (40.1% vs 49.5%), both comparisons statistically significant. Outcomes improved when ID doctors worked with a PA or NP.

By contrast, no significant differences were observed with any of the other metrics. This included by far the most important marker of HIV outcomes in 2024, which is viral suppression.

A study like this, of course, has limitations, most notably the non-randomized design, meaning those patients who receive primary care from ID doctors differed in many ways from those who went to non-ID specialists. While the investigators adjusted for demographic and other differences, residual confounding is always a possibility. I can certainly attest to the fact that at least here in Boston, many HIV patients who have ID doctors as their primary providers do so because they have no previous regular provider of any sort prior to their diagnosis.

And they can’t get a primary care doctor, an issue I’ll come to in a bit.

In addition, the “retention in care” metric is kind of weird, specifically:

… retention in care, defined as ≥2 elements of HIV care (including documented or self-reported outpatient encounters with an HIV care provider, HIV-related laboratory test results, ART prescriptions), at least 90 days apart.

For the record, many of my most stable patients long ago graduated to annual visits and blood test monitoring — admittedly in violation of guidelines that advocate for twice-yearly visits. Before you tsk-tsk at this “infrequent” care, how strong is the evidence that a person with HIV with virologic suppression for decades must have their labs checked twice yearly? I suspect these rock-solid stable patients wouldn’t qualify as being “retained in care” by the study’s definition, but they’re definitely not lost to follow-up.

In other words, my conclusion from this paper is that based on the metrics chosen, the quality of care for most people with HIV is pretty darn similar, regardless of their specialty, and that those who worked as a team — with an NP or PA — did a touch better with STI screening.

The results don’t surprise me much — HIV care in stable patients is, well, usually very stable. Hooray! It does not require a specialist’s expertise and raises the question once again why, in this phenomenally successful current ART era, we need ID doctors to do HIV primary care.

Indeed, my last take on this issue argued that it was time for us to move to a model more like the one we have for oncology or rheumatology patients, with ID specialists still playing a major role when HIV and its complications are active, and patients returning to primary care once stable. A periodic visit with an HIV expert can support primary care clinicians for issues related to ART switches and new treatment options, managing side effects and drug interactions, or clinical applications of advances in the field.

The clinical endpoints of the study also don’t get to the core reason why many of us ID doctors would be thrilled if our patients also had a generalist primary care doctor — especially our older patients with multiple medical comorbidities. Instead of these HIV-related endpoints, what if the study chose non-HIV-related measures of the quality of care, including control of hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular risk, guidelines-recommended cancer screening, and musculoskeletal pain?

In other words, these and other aging-related endpoints — none ID-related — would be far more relevant to the issue of primary care quality done by an ID specialist than the outcomes the investigators reported.

But before we ask our patients to switch their primary care to generalists, we once again must point out that this will be easier said than done. Primary care providers don’t grow on trees — or, if they do, these trees are pretty rare flora around these parts. A very important person recently asked me, on behalf of another big-time academic who just moved to Boston, for the names of good primary care doctors for him, his wife, and his two adult children.

Ha.

If she’d asked me for a thoracic surgeon, an ophthalmologist, an oncologist who specializes in breast cancer (to cite three recent successful examples of referrals), no problem. But a primary care doctor? The shortage is so bad that the giant healthcare system I work in, the largest in New England, stopped accepting new patients late last year. The wait even for established patients to get into see their primary care doctors for a non-urgent problem can be 6 months or longer.

You think these beleaguered PCPs could add people with HIV to their panel?

So we’ll continue to do primary care for now because there’s a desperate shortage of generalists. In some patients, we’ll be managing the only active medical problem they have, either because HIV is not yet stable, or they are otherwise healthy and their problem list is very short, with just one item: HIV.

In the older patients with stable HIV and multiple medical problems, we’ll do our best, with generous use of our subspecialty colleagues as needed — because some primary care is vastly better than none.

May 11th, 2024

Just in Time for Mother’s Day, Some Admiration and Gratitude

As I’ve written here before, I’m in awe of my mother — a smart woman who doesn’t celebrate Mother’s Day. So in place of celebrating, I’m going to use the holiday anyway as an excuse to share an event that highlights her strengths and resourcefulness. It has an ID theme eventually, so stick around to the end.

As I’ve written here before, I’m in awe of my mother — a smart woman who doesn’t celebrate Mother’s Day. So in place of celebrating, I’m going to use the holiday anyway as an excuse to share an event that highlights her strengths and resourcefulness. It has an ID theme eventually, so stick around to the end.

By way of background, my mother regularly uses New York City’s public transportation system, both the subways and buses. No big deal, one might think, so do umpteen million others. But the reason I mention it is because my mother is old. How old? Just look at me, and do the math for a good approximation. To be specific, she’s about to start her tenth decade.

Plus, she’s been living on her own since my father died, and continues to take care of pretty much everything in her life. This includes food shopping, cooking for herself and cleaning, and managing her surprisingly busy social and academic life. (She has a recent volunteer gig as a teacher, newsletter editor, and student.) She does these things without making a big deal out of it, so my brother, sister, and I take it for granted sometimes, overlooking how remarkable this independence is.

But a few months ago, I received a call that my mother had fallen while getting on the bus and was receiving care in an emergency room. She had no broken bones — thank goodness — but the fall took a sizable chunk of flesh from her left leg. Someone witnessing the injury thought she might need a tourniquet to control the bleeding.

We’ve all seen what falls can do. And it’s not just to older people — I’ve taken care of a man in his 30s whose life was irreversibly changed after falling from a ladder in his kitchen, striking his head, breaking his ankle, and triggering a series of neurologic and infectious complications that left him permanently impaired.

(I’m terrified of ladders. My wife thinks I’m a wimp, but I know better.)

Of course when it comes to falls, older people are especially vulnerable. Neuropathy, muscle weakness, vestibular instability, visual impairment, osteoporosis, and arthritis all come together to make falls way more common — and treacherous — in us as we age. The falls cause physical and psychological trauma that can profoundly weaken a person, leading to an amplifying cycle of debilitation and complications and dependency.

Think how many times you have heard, “He was OK before the fall …” or “Ever since the hip fracture, she’s never been the same.” Shudder.

In my conversations with my mother after the event, the tone of fragility in her voice was one I had never heard. Plus, she was barely leaving her apartment.

But rally she did:

- She openly shared with her family and friends how hard this process was — not an easy disclosure for a person generally independent and hesitant to reach out for help.

- From a skilled and incredibly kind plastic surgeon (Thank you, Dr. Schwartz!), she learned how to monitor and dress her sizable wound each day. I watched her do it, and think she could have had a career as a wound care nurse had she not been a journalist. What talent!

- She gradually increased her ability to get around again, first going for short walks outside when the weather was good, then starting to shop again on her own. She’s now back on public transportation.

- She managed to take a week of levofloxacin without destroying her tendons.

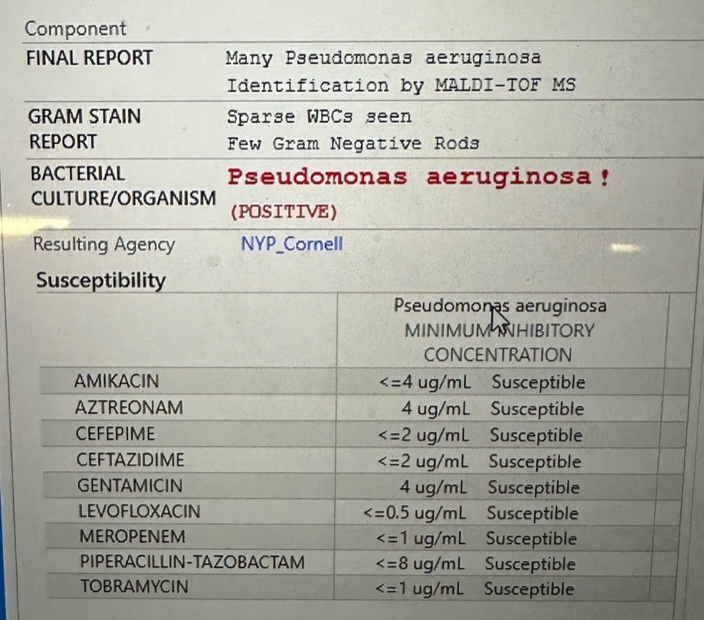

So we finally come to the ID part of this post. When the healing seemed to be slowing, with increased drainage, her plastic surgeon sent a wound culture, results of which he shared with me in this screen shot:

“Unless you have another thought, I’m going to start levofloxacin,” he wrote to me. Yes indeed, good plan — it was a superinfection of this widely open wound. Perhaps it was selected by the previous course of cephalexin she took. Or maybe it was just a “gift” from the flora of the New York City streets.

Ever curious, my mother had two questions, my answers in brackets:

Is this the infamous “flesh eating” bacteria? [No, that’s most often strep.] If this is a pseudo (meaning fake) monas, what’s the real monas like? [I have no idea.]

These are excellent questions, especially the second one.

I’m happy to report that with local care, and antibiotics, and time, the wound has ever-so-slowly healed. She’s “graduated” (her term) to just using a small bandage. No more visits to Dr. Schwartz.

So Happy Mother’s Day, Mom — glad you’re getting better, you did amazingly well. And be careful on those city buses!