An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

February 24th, 2013

Solve This Problem Please — Microbiology Results in Electronic Medical Records

Our hospital and affiliated practices have had electronic medical record (EMRs) of some sort for decades, so I’ve had my chance to try my hand at multiple “platforms,” both commercial and home-brew.

Our hospital and affiliated practices have had electronic medical record (EMRs) of some sort for decades, so I’ve had my chance to try my hand at multiple “platforms,” both commercial and home-brew.

(Weirdly — and I kid you not on this — a version of the first iteration from the 1980s is still around, running parallel to a more modern program. That old one remains the best at displaying simple things, like quickly showing a patient’s creatinine or white blood cell count.)

But one thing all these EMRs have in common is that they are pretty lousy at rapidly displaying microbiology results. I certainly see the problem — microbiology reports are a melange of obscure words, diverse numbers, and inscrutable abbreviations. And finding important results in a complex patient with dozens (or hundreds or thousands) of cultures is a major challenge for even the most tech-savvy clinician.

With current EMRs, it’s as if all the work that went into designing text macros and special “functionality” (cringe) had thoroughly drained the programmers’ brainpower, so by the time they got to the microbiology part they just gave up. I can just imagine a dialogue between team members as they faced writing the software for microbiology, realizing that there might be more to an EMR than just fast ways to spit out boilerplate text and nifty graphs:

Software Engineer 1: Hey, look at this — the clinician can now enter a complete normal physical examination just by typing “alt-PE”. And if they hit “control-alt-F7”, then it inserts three paragraphs that document a review of systems, patient education/counseling, and plans for follow-up — a guaranteed billing up-code.

Software Engineer 2: Cool! And watch this — we can graph this patient’s MCV, MCH, and MCHC going back to 1983 in 3 dimensions and using 9 colors. Nifty MP3 audio file adds a “swoosh” sound when the graphic appears.

Software Engineer 1: Awesome, great work! (Takes a swig of Red Bull, eats a few Doritos.) Hey, did you decide what to do with this information? (Hands over a piece of paper with the following printed on it.)

Specimen: Wound Date collected: February 16, 2013 Date reported: February 18, 2013 4+ PROTEUS VULGARIS GROUP VITEK AST-GN53 CARDAntibiotic Result ---------------------------------------------- Amikacin <=2 S Ampicillin >=32 R Cefazolin >=64 R Cefepime <=1 S Cefoxitin <=4 S Ceftazidime <=1 S Ceftriaxone <=1 S Ciprofloxacin <=0.25 S Ertapenem <=0.5 S Gentamicin <=1 S Levofloxacin <=0.12 S Meropenem <=0.25 S Nitrofurantoin 128 R Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole <=20 S Unasyn 8 S 4+ ESCHERICHIA COLI VITEK AST-GN53 CARD Antibiotic Result ---------------------------------------------- Amikacin <=2 S Ampicillin <=2 S Cefepime <=1 S Cefoxitin <=4 S Ceftazidime <=1 S Ceftriaxone <=1 S Ciprofloxacin <=0.25 S Ertapenem <=0.5 S Gentamicin >=16 R Imipenem <=1 S Levofloxacin <=0.12 S Meropenem <=0.25 S Nitrofurantoin <=16 S Tigecycline <=0.5 S Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole >=320 R Unasyn <=2 S

Software Engineer 2: (Wearily.) Nah … too tired. (Drinks some Mountain Dew. Gets excited again.) I know, let’s work on building in even more ways to guarantee that people will forget their username and password!

Maybe I’m not being fair to our friends in IT, but it seems someone should have figured out by now how to make information from the microbiology laboratory more digestible — maybe even searchable! And as our institution is in the midst of a giant shift — one could even call it an EPIC shift — to a new EMR, I’m hopeful we’ll see some innovative work in this tricky area.

Any bright ideas out there?

February 7th, 2013

Ciguatera Is Hot (But It Could Be Cold)

The news about the cases of ciguatera fish poisoning in New York (NY Times here, MMWR here) reminded me of several unusual things about this form of “harmful algal bloom,” as it is so artfully called by the experts.

The news about the cases of ciguatera fish poisoning in New York (NY Times here, MMWR here) reminded me of several unusual things about this form of “harmful algal bloom,” as it is so artfully called by the experts.

Specifically, here are six:

- Symptoms are bizarre. It starts out like a standard case of gastroenteritis — nausea and vomiting — but since ciguatera is a neurotoxin, here’s some of the weird stuff that follows: tingling, numbness, bradycardia, hypotension, muscle cramps, tooth pain, and most famously, “paradoxical dysesthesias”, where cold feels hot and hot feels cold. You ask 100 ID doctors about that last symptom, and 99 will shout, CIGUATERA! Just don’t do it in a crowded room.

- We can’t detect it. Vegetarian fish ingest the ciguatera toxin by eating algae off of seaweed and coral reefs; it’s then further concentrated inside larger fish (barracuda, grouper, snapper, amberjack, and surgeonfish) when these little fishies are eaten. (Don’t blame the big fish — this is what fish do — see image.) The problem is that the neurotoxin is odorless and colorless; fish with ciguatera toxin look and smell totally fine. Various folk remedies in Australia and the Caribbean (where ciguatera is common) have been proposed, including allowing cats to be our taste testers: if a cat eats some of the fish and is fine afterwards, then we will be too. Of course, this means adding a significant amount of time to your meal preparation — bad for work nights — and what if you don’t have a cat? Still, it sure beats the other method, which involves putting the fish in an ant pile, and seeing whether the ants avoid the fish — they apparently can tell. But would you want to eat the fish after it’s been in an ant pile? If you’re really worried, better get one of these gizmos, a Cigua-Check.

- We can’t prevent it. The toxin is heat- and cold-stable; our stomach acidity doesn’t touch it either. This means that fish that are perfectly handled, look and smell fresh, and are then cooked appropriately still can have high levels of ciguatera toxin. Freezing, pickling, and marinating also do nothing. What other kind of food poisoning is so occult and so impervious to best practices? Scary!

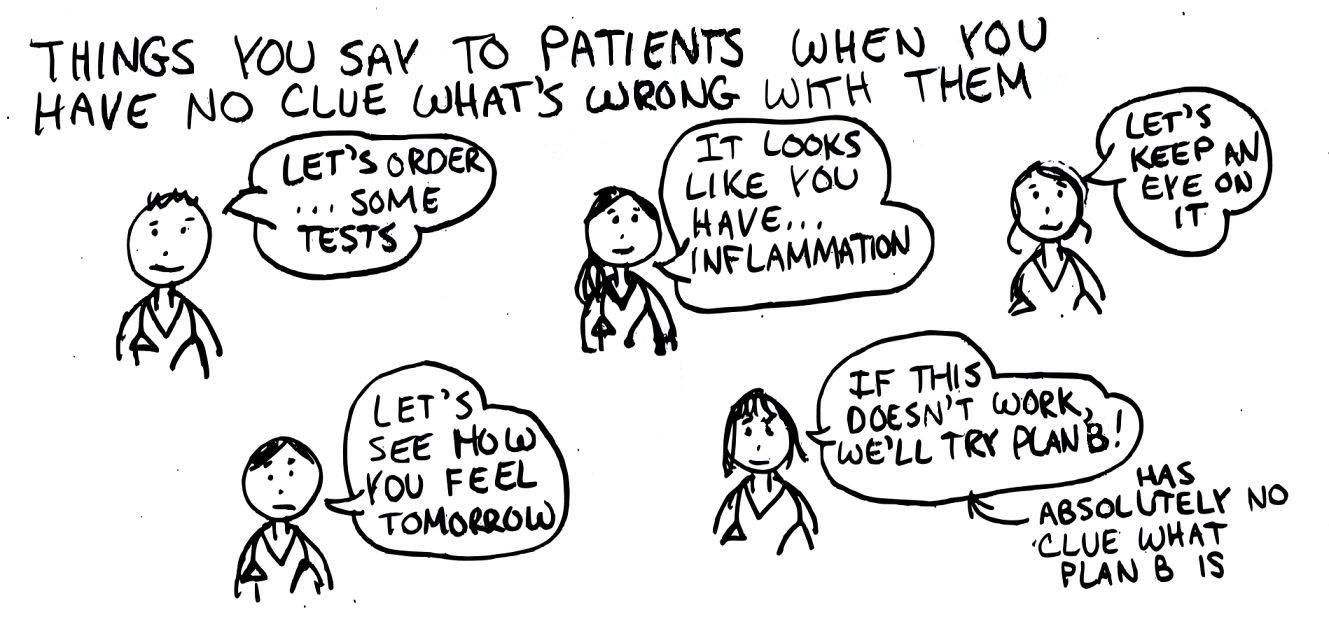

- Treatment is “supportive.” Beware any condition for which treatment is “supportive.” What this really means is that modern medicine is a lot like what it was several decades (OK, centuries) ago. We “support” the patient while he/she has nausea, vomiting, tingling, numbness, bradycardia, hypotension, muscle cramps, and tooth pain — and thinks that cold things are hot and hot things cold. No anti-toxin, no antibiotic, sorry. After a certain amount of time with this “support”, the patient slowly gets better, and we can take credit for it.

- The words are unfamiliar. We deal with bugs that have complicated names all the time, so barely bat an eye at Acinetobacter calcoaceticus–baumannii or parvovirus B19 or Diphyllobothrium latum. But the ciguatera toxin arises from marine dinoflagellates of the genus Gambierdiscus, specifically Gambierdiscus toxicus. What the heck is that?

- The ID boards are obsessed with marine toxins. Based on the number of practice board questions that deal with ciguatera, scombroid, and paralytic shellfish poisoning, you’d think that these conditions occur almost as frequently as the common cold. One way you can tell someone who is preparing for their ID boards is that they are suddenly experts on these weird diseases, casually mentioning scombroid as the possible cause of any sort of flushing, or red tide as the cause of diarrhea. Fortunately, this sort of diagnostic bias fades very quickly after taking the exam.

If the above six items are not enough, here’s a fun fact: Nobel Prize-winning novelist Saul Bellow had a severe case of ciguatera poisoning, using it as a key plot line in his final novel Ravelstein. One critic actually credited the ciguatera illness as making Ravelstein his favorite Bellow novel and concluded by making a bold proposal:

It certainly seems to me that a number of American novelists could benefit from a cruise to the Western Caribbean of the sort Bellow took, and as many sumptuous seafood meals (red snapper and barracuda especially recommended) as necessary to raise the level of their art through a slightly less-than-lethal dose of cigua.

I suggest that they bring their cats.

January 31st, 2013

When Your Language Gives Away That You Don’t Have a Clue

I was doing a clerkship in Medicine way back in my third year of medical school, and had this memorable exchange with one of the hospital’s Distinguished Professors during a case presentation on morning rounds:

I was doing a clerkship in Medicine way back in my third year of medical school, and had this memorable exchange with one of the hospital’s Distinguished Professors during a case presentation on morning rounds:

Me (nervous): This is a 72-year-old man admitted with chest pain. He has a past medical history notable for a heart attack 2 years ago …

Distinguished Professor (clearly annoyed): Paul, now that you’ve been in medical school for a while, you can start using the appropriate medical terminology — especially during case presentations. We don’t say “heart attack” — we say “myocardial infarction”, or the abbreviation “MI.” When you use the wrong term, you sound like you don’t know what you’re talking about.

Me (now feeling around 2 inches tall): Can I press the rewind button on this day and go back 10 or 15 minutes?

Distinguished Professor (confused): What do you mean …

Me (now feeling 1 inch tall): Never mind. This is a 72-year-old man admitted with chest pain. He has a past medical history notable for a myocardial infarction 2 years ago …

At least that’s how I remember it — it’s possible I didn’t say the joke about the rewind button, but I certainly was thinking it. Was he too harsh? Perhaps — after all, most people (even doctors!) know what a heart attack is, but I suppose I offended his sophisticated medical sensibilities and sounded incompetent. Oh well.

Anyway, I was reminded of this unfortunate event with a recent e-mail that came my way:

Dear Dr. Sax,

I am writing to invite you to submit a chapter on HIV Infection and the AID Syndrome [bolding mine] for our proposed on-line medical textbook, [insert name of latest UpToDate challenger here]. We have already assembled a substantial roster of specialists …

Now I have no idea whether this latest web venture will succeed, but in at least our world, they’re not off to a very good start. Because you can bet good money that the woman who emailed me is one of the few inhabitants of planet Earth who has used the bolded phrase above — “the AID Syndrome” — in place of the full abbreviation “AIDS.”

Makes “heart attack” sound like sophisticated medicalese at its most rarefied!

And while “AID Syndrome” is technically correct — Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome = AIDS = AID Syndrome — it sure does sound like she is completely clueless.

January 30th, 2013

“So You Think You’re an HIV Expert?”

I’ve been working with the folks over at Clinical Care Options (in particular, Elaine Seeskin) on a program entitled, “So You Think You’re an HIV Expert”, and it was just released here.

I’ve been working with the folks over at Clinical Care Options (in particular, Elaine Seeskin) on a program entitled, “So You Think You’re an HIV Expert”, and it was just released here.

It’s a series of quick interactive case presentations, and thanks to some nifty programming and great questions submitted by my colleagues Drs. Daar, Eron, Gallant, Hodder, and Powderly, it’s actually fun.

(Yes, I know — ID geek.)

Do it on-line, or on your hand-held device (apps available for iPhone, iPad, Android); programs on HCV and multiple myeloma also available.

Two other quick comments:

- Will anything require more substantial revision in the next 1-2 years than the one on hepatitis C?

- I started the one on multiple myeloma, and realized very quickly the answer to the question of whether I’m an expert is emphatically NO.

Enjoy!

January 21st, 2013

Must-Read Piece: “Fever of Too Many Origins”

Every so often a commentary gets something just right, and fortunately we have an example in this week’s New England Journal of Medicine.

Every so often a commentary gets something just right, and fortunately we have an example in this week’s New England Journal of Medicine.

Entitled “Fever of Unknown Origin or Fever of Too Many Origins?”, it’s the best depiction I’ve read about doing ID consults in the intensive care unit (ICU). The author, Harold Horowitz (who has practiced ID in tertiary care hospitals for 3 decades), contrasts the classic Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO) with the arguably more common Fever of Too Many Origins (FTMO), which is all-too recognizable for those who do hospital-based patient care.

These are patients “who have traumatic brain injury, other neurologic events, or dementia; are mechanically ventilated; have some combination of urethral, central, and peripheral catheters placed; have recently undergone surgery; and are already receiving multiple broad-spectrum antibiotics.”

In other words, they might have originally had diverse medical and surgical problems, but they’ve now entered the narrow portion of the ICU funnel, and are strikingly similar.

There are many quotable passages, but the following is my favorite:

As the keeper of the antibiotics, should I be a conservative or a cowboy? Should the current antibiotics be continued, changed, or stopped? If there are no prescribed antibiotics, should I recommend some? These are interesting questions in the abstract, but there is a real patient suffering, a family with questions, and medical teams awaiting my opinion. There are no evidence-based studies and there is no guidance on which potential source of fever is the single appropriate one to treat. Frequently, the treatment approach is like playing Whac-A-Mole: positive cultures are treated sequentially — pneumonia, then catheter cultures, then urine cultures. When the fever persists, the cycle begins again.

Whac-a-Mole — what a great analogy! I’ve written before about my frustrations with ICU-related Infectious Diseases (here and here), but Horowitz does it better. I found myself nodding with recognition time and time again.

While the tone of the piece is understandably melancholy — these are patients not for ID case conference, but for “family conferences that include plans for palliative care” — I was left with a somewhat more hopeful thought. Namely, that once we recognize the eerie similarity of these ICU ID consults, then perhaps we can evaluate their optimal management in a controlled clinical trial. Something like this:

Inclusion criteria: ICU stay > 1 week; endotracheal intubation; fever > 101.5F; multiple possible sources of fever but no obvious single source (e.g. bacteremia).

Intervention: Randomization to one of two treatment strategies: 1) Initiate or change to empiric broad-spectrum antibiotcs with cessation after 3 days if cultures are unrevealing and there is no objective clinical improvement; or 2) Standard of care.

Primary endpoint: All-cause mortality.

Secondary endpoints: Infection-related mortality, length of ICU stay, antibiotic exposure, adverse effects of antibiotics (including C diff), bacterial resistance, fungal superinfection, cost, etc.

Primary funding source: The National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Sure beats Whac-a-Mole.

January 17th, 2013

Why the Results of the C Diff Study (You Know Which One) Were No Surprise

In cased you missed it, fecal transplant — use of poop from a healthy donor, which is then infused into the colon either from above (nasogastric tube) or below (colonoscope) — is unquestionably the most effective treatment for people who have multiple recurrences of C. difficile colitis (C diff).

We know this because of a randomized study just published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Here’s the punch line:

The study was stopped after an interim analysis. Of 16 patients in the infusion group, 13 (81%) had resolution of C. difficile–associated diarrhea after the first infusion. The 3 remaining patients received a second infusion with feces from a different donor, with resolution in 2 patients. Resolution of C. difficile infection occurred in 4 of 13 patients (31%) receiving vancomycin alone and in 3 of 13 patients (23%) receiving vancomycin with bowel lavage (P<0.001 for both comparisons with the infusion group).

A slam dunk win for fecal transplant, so much so that there was no point even completing the study. In the New York Times right now, coverage of the paper is actually their most e-mailed story, and even the non-clinicians in our office are buzzing about it.

(Inevitably with giggles and jokes. This stuff is hard for people to talk about, but they somehow can’t resist.)

But many of us in the ID world knew that fecal transplant was going to work great for C diff even before this study. How did we know?

- The current treatment for recurrent C diff is terrible. Metronidazole, vancomycin, and fidaxomicin all share a basic problem. They are antibiotics. And antibiotics cause C diff to begin with. Fail.

- Probiotics don’t do much. As much as I’d wish to say otherwise, the efficacy data for probiotics in preventing C diff relapse are marginal at best. Remember, lots of what makes up “normal” flora can’t even be cultured — so how do you put those bugs in a capsule? Looks like we need to use the real thing to get those normal bacteria back.

- The published uncontrolled studies on use of fecal transplant were extraordinarily favorable. In this systematic review, the cure rate was 92%. And remember, the people referred for these procedures were horribly weakened by recurrent C diff, and many had severe underlying medical conditions.

- Our limited anecdotal experience confirmed that this actually works. One of the local gastroenterologists has been doing this for a couple of years. Our first referral was an 84-year-old man with two forms of cancer, diabetes, and 5 episodes of recurrent C diff, bad enough that he’d lost more than 15% of his baseline weight. One fecal transplant procedure — C diff gone.

- For patients and doctors to keep doing something this disgusting, it must be effective. There’s a reason we snicker and jest when discussing fecal transplants — it’s gross and makes us uncomfortable. Just look at all the various euphemisms out there for this procedure — intestinal microbiota transplantation, fecal biotherapy, bacteriotherapy, human probiotic infusion. (That last one is my personal favorite — you can even call it “HPI.”) Anything to get rid of that nasty image of having other people’s poop inside of us, yuck. Sorry for mentioning that.

So consider the publication of this landmark article as a way of getting the word out to the rest of the world that this unsavory — but undoubtedly very effective — treatment is here to stay.

Let’s just hope they can find another important job for C diff Cliff.

January 16th, 2013

More Evidence That Early HIV Treatment — REALLY Early — Is Beneficial

Management of recently acquired HIV infection — especially acute HIV, pre-seroconversion — has long been controversial, with the risks and benefits of treatment versus observation debated now for nearly two decades.

Management of recently acquired HIV infection — especially acute HIV, pre-seroconversion — has long been controversial, with the risks and benefits of treatment versus observation debated now for nearly two decades.

(Yes, it’s been that long since the publication of this controlled trial of zidovudine monotherapy. Amazing.)

On the risk side of the equation is the toxicity of lifelong treatment, especially since some patients may have normal or near-normal CD4 cell counts after recovery from acute HIV, and may remain asymptomatic for many years. Benefits include preservation of immunologic function, reduction in transmission risk to others, and even potentially a reduction in the HIV reservoir — the last making patients who are treated for recently acquired HIV of particular interest for HIV cure strategies.

Now, two studies have been published in the New England Journal of Medicine that strongly suggest that we manage early HIV infection the same way we do long-established disease — that is, with antiretroviral therapy (surprise!), and the sooner it’s started, the better.

- Le and colleagues conducted a prospective observational study involving 468 patients (95% men) in San Diego with acute or early HIV infection — 213 who initiated ART within 4 months after HIV acquisition and 384 who did not receive it until later. Sixty-four percent of patients treated early achieved the primary endpoint (CD4 recovery to ≥900 cells/mm3 during 48 months of observation) versus 34% of those treated later (P<0.0001). For those treated later, the median time to CD4 count < 500 — a threshold at which the clinical evidence of treatment benefit becomes much stronger — was only 12 months, suggesting that even if treatment is not started early, it is likely to be needed relatively soon.

- In the open-label SPARTAC Trial, conducted at sites in Europe, South America, Australia, and Africa, 371 patients (60% men) with primary HIV infection (variously defined) were randomized to receive 12 weeks of ART, 48 weeks of ART, or no ART (standard of care). The primary endpoint was either a CD4 count 3 or initiation of long-term ART. During a median follow-up of 4.2 years, only the 48-week treatment group demonstrated a delay to CD4 count 3, with 29% falling to this level versus 40% of the 12-week group and 39% of the no-ART group. The proportion who eventually went on long-term treatment initiation was similar among groups. In addition, 36 weeks after the end of short-course therapy, the mean change in HIV RNA level from baseline was significantly greater in the 48-week group than in the no-ART group (difference, –0.44 log10copies/mL). Among participants in the 48-week group, treatment started closer to the time of HIV acquisition appeared to confer greater benefit. (Quick aside — HIV-specific CD4 or CD8 immune responses did not correlate with the outcome, raising questions about whether these laboratory-based findings have any clinical relevance, or are mere associations.)

There are of course limitations to these studies, most notably the non-randomized design and skewed demographics in the first, and the fact that treatment interruption makes both of the treatment strategies in the second study of limited relevance today. Furthermore, the various definitions of early HIV infection — a problem which has plagued this field from the outset — imply a very heterogeneous patient population: In the second study, some participants had acute symptomatic HIV infection pre-seroconversion at one extreme, and others were diagnosed solely based on a newly positive HIV antibody. And neither study had sufficiently long follow-up to provide hard clinical endpoints of the benefits of early treatment.

These limitations notwithstanding, there is a consistent message from the aggregate results, which is that treatment of early HIV infection — and the earlier the better — is associated with significant improvements in the most important surrogate markers of HIV disease, the CD4 cell count, and the HIV viral load. For these outcomes alone, early treatment is warranted — especially since we’re generally recommending treatment for everyone else with HIV already!

January 11th, 2013

How to Make the Flu Vaccine More Popular, Warts and All

In a week that saw both our hospital’s influenza-induced bed crunch make the New York Times, and my son, mother-in-law, and me succumb to this seasonal plague despite our receiving flu shots, I have been highly attuned to all things influenza.

But the focus here will be on that perennial whipping boy of preventive Infectious Diseases, the flu vaccine. Let me get it out of the way that I unequivocally believe that it’s our best way of preventing flu, and that I would never skip it. Nonetheless, it’s far from perfect, which is why in the court of public opinion, it just can’t win.

Why do most universal flu vaccine campaigns seemed doomed from the outset? Let me list the ways, some of them the fault of the vaccine, some just human nature:

- It has to be repeated yearly. Like magazine subscriptions renewals, membership dues, car inspections, and taxes, the flu vaccine comes round every year and induces the same feelings of nauseating weariness. Again? You mean I need that shot already? Didn’t I just do it? And will it even work this year? All right, go ahead. Medically savvy patients note that we’re not making them repeat any of the other shots yearly, which must imply to them a serious weakness in our vaccine.

- It doesn’t always work. Estimates of flu vaccine effectiveness vary widely, so I like to cite the 70% figure from this study rather than the more discouraging CDC’s aggregate data of 60%. And then I add some motivating language such as, “but it works better in some people than others, so let’s be on the optimistic side.” Plus I mention that all doctors and nurses get the vaccine, which though a bit of a lie, is at least true about ID docs/nurses.

- Many people think it works even less well than it does. Flu season just happens to coincide with the seasonal increase in all kinds of other respiratory tract infections, and it’s inevitable that patients with bad colds will blame that on the failure of the flu vaccine. Plus, approximately 32.56% of the population use the term “stomach flu” to describe various short-term gastrointestinal ailments, and regardless of what that term actually means, it’s 100% certain that the flu vaccine does nothing to prevent them. More failure! Even the above-mentioned Times article compounds this confusion by starting the piece on influenza, yet including several paragraphs on norovirus — just because, um, it’s sort of related, I guess. (It’s not.)

- “It gives me the flu.” I find it truly mystifying why so many people believe that the flu vaccine gives them the flu, but regardless, it’s either the top reason cited by vaccine refuseniks or a close second to, “I never get the flu, so I don’t need it.” My hunch is that people believe the flu vaccine gives them the flu because 1) colds are common and 2) they once got a bad cold (the “flu”) shortly after getting the vaccine. QED.

- It has to be matched each year with the predicted circulating influenza viruses. Sometimes the match is a good one (this year it is), sometimes less so. Unfortunately, in the absence of an all-knowing, popular Nate Silver-like projection guru — someone who updates his/her predictions on a regular basis for the public to see, and does it in plain language — the process of matching the vaccine to the circulating viruses is not for the faint of heart. (I dare you to read this all the way through.) This stuff is rough going even for most doctors, hence it’s no wonder that the public is skeptical on an annual basis. For the record, this is what’s in this year’s vaccine (in case you want to make one at home): an A/California/7/2009 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus, an A/Victoria/361/2011 (H3N2)-like virus, and a B/Wisconsin/1/2010-like virus (from the B/Yamagata lineage of viruses). Piece of cake.

- Weird stuff happens. Just like no vaccine is 100% effective, none is 100% safe either. The sheer volume of flu vaccines given every single year means that bad stuff is numerically more likely to happen with the flu vaccine than with others, at least in adults. Some of these linked events will be little more than anecdotes — do you really think your golf game was worse this week is because you just got a flu shot? — but some will be real, e.g. the 1976 swine flu vaccine and Guillain-Barré syndrome. These associations are hard to shake, and not a year passes where I’m not asked about the flu vaccine and Guillain-Barré, along with much more tenuous (really nonexistent) links such as flares of multiple sclerosis, transplant rejection, arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Given the above challenges, what can we do about it?

Seems what we need is a truly trustworthy spokesperson for the flu vaccine, someone who will take on what Magic Johnson did for HIV. He or she will calmly recommend the vaccine, reassure people about its safety, acknowledge fears and misconceptions — perhaps even mention that even if the vaccine doesn’t work, it probably makes the breakthrough case of flu milder — how many people know that?

So with the help of this nice list of the most Trustworthy Celebrities, plus some of my regional/personal biases, I ask you to help choose our Flu Vaccine Celebrity Spokesperson. I am 100% sure that after hearing of their nomination, they will quickly drop whatever project they are doing and volunteer their time for this important public health effort.