An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

April 10th, 2013

Simeprevir and Sofosbuvir Submitted to FDA — Clock Ticking on Boceprevir, Telaprevir, Even Interferon

Two weeks, two companies, two press releases, two future HCV drugs that begin with “S”:

Two weeks, two companies, two press releases, two future HCV drugs that begin with “S”:

- March 28, 2013: Janssen Research & Development announced that it has submitted a New Drug Application to the FDA seeking approval for simeprevir (TMC435), an investigational NS3/4A protease inhibitor, administered as a 150 mg capsule once daily with pegylated interferon and ribavirin for the treatment of genotype 1 chronic HCV in adult patients.

- April 8, 2013: Gilead Sciences announced that it has submitted a New Drug Application to the FDA for approval of sofosbuvir, a once-daily oral nucleotide analogue for the treatment of chronic HCV infection. The data submitted in this NDA support the use of sofosbuvir and ribavirin as an all-oral therapy for patients with genotype 2 and 3 HCV infection, and for sofosbuvir in combination with ribavirin and pegylated interferon for treatment-naïve patients with genotype 1, 4, 5 and 6 HCV infection.

For several years now, all clinicians who see patients with hepatitis C have been promising them better treatments “soon”, with admittedly little precision about exactly what this “soon” actually means.

But with these filings, we have a pretty good idea. It will be less than a year — maybe much less. Why is that?

- The FDA has roughly 10 months to review these applications. (The exact timing is somewhere on the FDA web site, see if you can find it.)

- These two drugs have looked pretty great in clinical studies to date.

- The bar to leap over to be substantially better than current standard -of-care treatment for HCV isn’t exactly high — a fact that could get at least one drug, if not both, priority review and even more rapid approval.

- One of my patients has joked that I’ve been saying “in a few years” for availability of better HCV treatment options for at least “a few years” now — so my time is up.

Of course, stuff could happen that holds up the approvals. A toxicity could arise that hasn’t been reported previously, or a tricky drug-drug interaction could crop up. Or the sun could explode.

But if these things don’t happen, then for patients with HCV genotypes 2 and 3, a non-interferon option looks like it’s right around the corner — sofosbuvir and ribavirin. For those with genotypes 1 and 4, a shortened, more effective, and all-round improved interferon-based regimen will arrive at the same time — pegylated interferon/ribavirin plus either simeprevir or sofosbuvir.

And even better, how about an off-label combination of these two new drugs as in this clinical study — in which case the interferon can be dropped entirely, right?

Let the choir sing out when that happens, and enjoy a hearty celebratory brunch at the famous Cambridge deli pictured above in honor of the new regimen.

April 5th, 2013

Another “Important Advance” in HIV Vaccine Research?

On reading this other real news about a single patient and how it may shape the future of HIV vaccine research, I decided to write the following fake news, drawing liberally on many similar stories over the years:

On reading this other real news about a single patient and how it may shape the future of HIV vaccine research, I decided to write the following fake news, drawing liberally on many similar stories over the years:

Scientists today reported a discovery that could finally pave the way for an effective AIDS vaccine. In the study, published in the journal Science, they describe a single person who lacks evidence of HIV despite extensive testing using even the most sensitive tests.

Gustav Blinkerhood, a research scientist from the University of Minnesota and the lead author on the paper, was quick to caution that the patient may have tested negative for HIV simply because he doesn’t have it, and never did.

“We cannot find any traces of the virus,” said Blinkerhood about the case. “All the tests are negative.”

Not only was there no direct evidence of HIV — the virus that causes AIDS — the patient also lacked the tell-tale antibodies that are present in someone exposed to HIV who has acquired it.

Blinkerhood’s research team plans further testing of other people who don’t have HIV. “Our hypothesis is that they will test negative as well,” he said.

Researchers have been stymied for years in their efforts to develop an effective HIV vaccine because the virus changes so darn much, evading the immune system. It is hoped that this study of uninfected people who test negative for the virus will spearhead a new round innovative research.

Dr. Anthony Fauci*, the Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, praised the scientific rigor of study yet also stated that the development of an AIDS vaccine remains a major challenge.

“In is important that I comment on all widely publicized HIV research in this way,” said Dr. Fauci. “And that’s what I’m doing right here.”

Dr. Jane Greezley, a Professor of Microbiology at Tufts University, wrote an accompanying editorial in the journal. She agreed with Fauci, adding “I was a reviewer of this paper, and recommended it be accepted for publication, then the editors asked me to write this commentary — maybe they’ll accept my next paper in return.”

The patient, who is entirely healthy and has requested anonymity, is named Charles Gallagher. He lives in Minneapolis at 17 Fairfield Road, and his cell phone number is 292-344-8664.

(*Hey, if I had a big HIV news story, I’d call him too!)

Yes, this should have been posted on April 1. But I was too excited by Infectious Diseases Exotica Day on Physician’s First Watch, sorry.

April 2nd, 2013

Banner Day for ID on Physician’s First Watch, and a Big Pitch to Sign Up Now

Every weekday morning, right around the time the rest of my family gets up, the smart people at Physician’s First Watch send me an email listing the top medical news stories of the day.

Every weekday morning, right around the time the rest of my family gets up, the smart people at Physician’s First Watch send me an email listing the top medical news stories of the day.

Imagine my delight yesterday when the following were deemed worthy for specific mention:

- Coccidioidomycosis! Valley fever cases on the rise in the USA. You too can learn how to spell and pronounce it (only wimps say “cocci”), provided you practice, practice, practice…

- Mycobacterium abscessus!! Looks like person-to-person transmission can occur, at least according to this paper in the Lancet.

- Q fever!!! The Centers for Disease Control have issued guidelines on diagnosis and management of Coxiella burnetii (Q fever), thereby fulfilling what was undoubtedly a burning national need. (Sarcasm used with the utmost affection, CDC.)

Not only was I delighted by this threesome, but confess a bit surprised as well. After all, it’s not as if these are garden-variety ID problems; in fact, if all three of these diagnoses showed up in an ID case conference, it would be one heck of a meeting. By chance, one of these — M. abscessus — did get discussed at our conference this week, and boy was I prepared. Thank you, PFW.

All of which is a way of putting in a plug for Physician’s First Watch, which is concise, free of charge, and well worth the 5 seconds it takes to sign up for it.

Even when the coverage does not involve the World’s Greatest Medical Specialty.

March 28th, 2013

Poll: How Often Do You Measure CD4 Cell Counts?

Over in Clinical Infectious Diseases, a recent study pretty much nails the fact that routine measurement of CD4 cell counts in clinically stable patients is an all but useless exercise. As summarized by Abbie Zuger in Journal Watch, here’s the key finding:

When patients with an unrelated cause for an alteration in CD4-cell count such as severe infection, chemotherapy, or interferon treatment were excluded from the analysis, not a single patient in any group had a dip in CD4 count below 200 cells/mm3 after 2 years of continuous virologic control.

So I’ve been singing this tune for a while (large nose-enhancing video here), and as a result have been trying for some time to get my stable patients to reduce the frequency of CD4 monitoring — or even, as I note in this editorial, give it up entirely!

And has this been a successful effort? For some patients, yes, but for others it’s hopeless — they simply can’t understand that this test, which was the cornerstone of HIV monitoring for decades, now provides us with information that has no role in determining what we do therapeutically (provided the viral load remains suppressed).

And has this been a successful effort? For some patients, yes, but for others it’s hopeless — they simply can’t understand that this test, which was the cornerstone of HIV monitoring for decades, now provides us with information that has no role in determining what we do therapeutically (provided the viral load remains suppressed).

In short, we order the test for emotional and sentimental reasons only — it’s reassuring to patients to hear that their CD4 cell count is stable, and we’ve been doing it for so long, why stop now. But are these good enough reasons? Before you answer in the affirmative, remember that unexplained drops in CD4 (which are not uncommon) have the opposite effect, and require frequent education about why the result won’t change our patients’ treatments.

So I ask you, providers of HIV care, the following burning question:

March 23rd, 2013

ID Doctors, Pets in the Medical History, and a Cute Puppy

One of the things Infectious Disease doctors get teased about by our non-ID colleagues is our inclusion of pets in medical histories.

One of the things Infectious Disease doctors get teased about by our non-ID colleagues is our inclusion of pets in medical histories.

It’s part of the social history, where we list a grab bag of potential “exposures” that increase the risk of infection — where someone is from, what they do, plus travel, dietary practices, sex, drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, and PETS!

In our defense, to our critics I remind them that we take the best histories — if you don’t believe me, read this — but must acknowledge that the pet thing is not always relevant. Ok, it barely ever is relevant. But it sure is fun.

In order to examine this issue more closely, I offer the following anecdotes and observations — none of them leading to brilliant pet-related diagnoses — taken from real life clinical practice:

- I once cared for someone who was very funny — so much so that he was funny for a living. When I asked him if he had any pets, he told me he had 15 cats. How did he do that? His response: “Easy — when you have 14 cats, you get one more, and if you have 16, one of them dies or runs away.” (FYI, I think he stole this line.)

- A patient told me she was taking her dog’s deworming medicine for pinworm. She didn’t have pinworm, by the way, but these were her symptoms, so she was convinced. (Warning: video is kind of yucky.) The medication she was taking was something called “Panacur” (fenbendazole). While I like that name — Panacur sure sounds like it cures a lot of things — it’s only approved for use in sheep, cattle, horses, fish, dogs, cats, rabbits and seals.

- Dept. of Irony: Asked someone recently if he’d received his zoster vaccine, and he told me that he refused because the cost was way too high ($300), and not covered by insurance. Later, when I asked him about his pets, he told me he’d paid nearly $3000 for his dog’s various orthopedic ailments.

- It used to be that none of our patients from Haiti had pets. Now lots do. Is there a PhD anthropology thesis in there? I’d better ask Paul Farmer.

- Every so often, someone tells you he/she has a pet turtle, frog, or lizard. Should you warn them of the risk of salmonella, and ruin their fun? And if not, why ask? These are the kind of tough dilemmas ID doctors face every day.

- My first opportunity to witness the occasional absurdity of this pet obsession was during my fellowship. One of my attendings, an extremely detail-oriented type even by ID standards, was consulted by a trauma surgeon on a comatose man with fevers during a lengthy hospital stay after a motorcycle accident. She wrote in her note, “has parakeet named Fruitloop.” This surprised me, as the patient didn’t seem like the parakeet type. And I still wonder — how did my attending find this out? Here’s the dialogue that might have happened:

ID doctor: Does he have any pets at home?

Patient’s Mother (surprised at the question): Yes, he has a bird. We’re taking care of it since the accident.

ID doctor: What kind of bird is it?

Patient’s Mother (even more surprised): It’s a yellow parakeet.

ID doctor: What is the bird’s name?

Patient’s Mother: Fruitloop. (A pause.) Excuse me doctor, are you out of your mind?

So here’s a confession. This post is an excuse to show off a picture of our new puppy.

His name is Louie.

March 15th, 2013

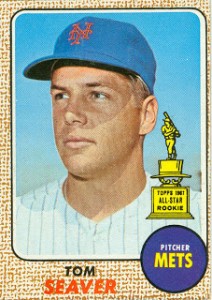

Tom Seaver Has Lyme Disease, and the Baseball, ID, and Wine Trifecta

In my never ending quest to link up various passions in life — especially baseball and Infectious Diseases — I bring you this news story:

In my never ending quest to link up various passions in life — especially baseball and Infectious Diseases — I bring you this news story:

But for Seaver, after months of private denial, the scariest incident came when his head vineyard worker, who has been with him for seven years, came into the house one morning. “I looked at him and I didn’t know his name,” Seaver said. That’s when Seaver’s wife, Nancy, made him finally go see a doctor. After Seaver underwent an examination and a battery of tests, the doctor informed him that he did not have dementia, had not had a stroke and was not terminally ill. He had Lyme disease.

Fans of Tom Seaver will be pleased to hear that he’s doing better. Additional thoughts:

- His case sounds familiar, as the worst complications of Lyme not surprisingly occur when the diagnosis is delayed for months. These are truly tough cases, much in need of both better treatments and some sort of marker of disease activity.

- One of the first baseball games I attended in person was this one at Shea Stadium. Eleven strikeouts, no walks, 1 (9th inning) hit — game score of 96! Wow! Probably way more than you want to know about game score here — it’s basically a marker of pitching dominance. Anything over 90 is outstanding, over 100 of historical greatness.

- But that’s not all: Seaver and his wife own a highly esteemed Napa Valley vineyard (check out the top of that wine bottle), and their limited-production cabernet regularly scores in the mid-90s in the wine press, once scoring a 97. That’s almost as rare as a game score of 96 — think of it instead like an ERA of under 3.00 for the season. And yes, it’s another reason why this Seaver story caught my eye.

Get well soon, Tom Terrific!

March 10th, 2013

Really Rapid Review — CROI 2013, Atlanta

As noted previously by Carlos del Rio in his nice summary, the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) turned 20 this year. It also made it’s first-ever stop in Atlanta, home of many things that begin with “C” — CDC (note that insiders rarely say, “the CDC”), CNN, Coca Cola, and Carlos himself.

As noted previously by Carlos del Rio in his nice summary, the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) turned 20 this year. It also made it’s first-ever stop in Atlanta, home of many things that begin with “C” — CDC (note that insiders rarely say, “the CDC”), CNN, Coca Cola, and Carlos himself.

I’ll spare you the boring saga of just how messed up the travel was back to the Northeast as the conference came to a close — ugh — and jump right in on this Really Rapid Review™, loosely organized by prevention, treatment, and complications.

- Baby “cured” of HIV. Need I say more? Nah.

- In the VOICE study of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), none of the interventions worked — not oral TDF, oral TDF/FTC, or vaginal TDF gel. The adherence was dismal — it seems that only around 25-30% of the more than 5000 African women took their assigned treatment. At the conference, the “joke” was that at least the side effects were minimal — hey aren’t we a funny bunch of HIV researchers. The unfunny part was the alarmingly high HIV incidence among the participants, especially the young women in South Africa.

- No excess in HIV incidence or high risk behavior after stopping PrEP in the iPrEx study. Quick aside — do you like it when the study title is declarative about the result, as in these two papers? I do.

- Interestingly, even after the 052 results were released to the study subjects, many of those randomized to deferred therapy still chose not to initiate ART. Several possible explanations — they felt fine, they had many months of clinical stability, and importantly were initially counselled that their CD4 cell counts were high enough to defer therapy.

- Can the long-acting injectable integrase inhibitor GSK1265744 be the answer to PrEP adherence issues? We’re talking REALLY long acting, with protective drug levels potentially months after the dose. If it’s an injection every 3 months, this crazy idea just might work.

- Here’s an interesting diagnostic tidbit — the 4th generation combined HIV antigen/antibody tests may have a small “window” when p24 antigen turns negative before the HIV antibody becomes detectable, analogous to the hepatitis B surface antigen/antibody window. The combined test is still better than antibody alone for early infection, but it does highlight how useful it would be to have HIV RNA (viral load) licensed for diagnosis.

- More evidence that the earlier treatment is started after HIV acquisition, the smaller the size of the latent reservoir. More reasons to treat (rather than observe) patients with acute HIV.

- In a CDC-sponsored study of 10 sentinel sites in the USA from 2007-2010, the prevalence of transmitted drug resistance among newly diagnosed patients was 16%. Breakdown by drug class: NNRTI 8.1%, NRTI 6.7, and PI 4.5%. Compared with their prior report, the overall rate is around the same, while NNRTI resistance is rising. Given the improvement in virologic suppression rates that happened in the late 2000s, I expected transmitted drug resistance to drop — maybe next time!

- In a randomized, double-blind clinical trial in over 700 treatment-experienced patients, once-daily dolutegravir was superior at 24 weeks to twice-daily raltegravir. Every year there’s a study that gets the award for “CROI Poster That Most Deserved an Oral Presentation,” and this is the 2013 winner. FDA approval of dolutegravir expected this summer.

- On the topic of dolutegravir, treatment response in 2 treatment-naive studies was consistent among various demographic and clinical subgroups. A third study (vs. boosted darunavir) is ongoing.

- If a patient has failed treatment using the three original drug classes (NRTI, NNRTI, PI), and has more than two active drugs besides NRTIs on resistance/tropism testing, do you need to include NRTIs in the salvage regimen? According to this ambitious clinical trial, the answer is no. Virologic responses were similar, with or without the NRTIs. Oddly, there were six deaths in the NRTI arm, zero in the “no nukes” arm — hard to see that as being related to anything but chance, as the causes of death did not seem drug-related, but it’s weird nonetheless.

- After a first-line failure of a standard two NRTIs + NNRTI regimen, lopinavir/r + NRTIs and lopinavir + raltegravir were similar in efficacy. One might expect the latter to be better (two new fully active drugs, after all), but most likely adherence was the key determinant of outcome in both study arms. This was a poster too, by the way — winner of second place in that above-mentioned award.

- Could tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) be a safer version of tenofovir (TDF)? In this phase II study, renal and bone parameters were both significantly better with TAF than TDF. Virologic outcomes were similar, but the study was not powered for efficacy. Phase III studies ongoing.

- Maintenance therapy after virologic suppression with a two-drug regimen of raltegravir + maraviroc didn’t work very well (5 of 44 with virologic failure), but the study authors sure had a nifty title — ROCnRAL.

- Splitting up the TDF/FTC/EFV didn’t impair virologic suppression in this report of 478 stable patients switched to separate TDF, 3TC, and EFV. Would be interesting to see how this flies in a more challenging group of patients — e.g., inner-city Baltimore — and for a longer duration.

- Cenicriviroc is a CCR5 inhibitor that also blocks CCR2 — and hence may have anti-inflammatory properties; it was compared with EFV in this phase II study. There were more virologic failures in the cenicriviroc arm, more discontinuations for adverse events in the EFV arm, but the study was small and the formulation highly problematic. Hard to know where this is going — is cenicriviroc potentially a replacement for “key third drug”, or will it be coformulated with 3TC and replace one of the NRTIs? Or will drug development stop, since it’s not as if there’s a driving need for another CCR5 antagonist? We’ll see.

- A first look at at the antiviral effect of MK-1439, an investigational NNRTI. Decent potency, QD dosing, good activity vs 103N, 181C, 190A. The issue, of course, is that NNRTI development has been so very challenging — lersivirine the most recent example.

- In the COAT study of timing of ART initiation in cryptococcal meningitis, the early ART group had significantly shorter survival, prompting early termination of the study. Those with the lowest CSF WBC and impaired mental status did particularly poorly with early ART. A truly important study, done in Africa but with global implications.

- Do OIs still happen once the CD4 is > 500 on ART? According to this massive cohort study, the answer is yes, but very, very infrequently. And here’s a surprise — OIs are more common in those with CD4 500-750 than >750. With such rare events, the sample size needed to be gargantuan — how does 149,730 sound?

- A first report of treating acute HCV (all in HIV positive MSM) with three drugs — peg IF, RBV, and telaprevir. Not surprisingly, it works, and works fast.

- Preliminary results were encouraging in two studies (telaprevir in one, boceprevir in the other) for HIV/HCV coinfected patients with prior HCV treatment failure on IF/RB, but …

- Enough about that inferferon stuff already! Three IF-free approaches: 1) ABT-450/r + a non-nucleoside polymerase inhibitor + RBV; 2) simeprevir + sofosbuvir +/- RBV; and 3) sofosbuvir + ledipasvir (formerly GS-5885) + RBV. Bottom line on all three was that results were outstanding, virtually guaranteeing that interferon-based treatments will soon be a thing of the past. The third of these studies — 100% response in both naives and prior null responders — provided one of the more exciting clinical trial results I’ve seen in years, small sample size notwithstanding.

Apologies if I’ve left out your favorite, would love to hear what I missed — and I reserve the right to add a few based on your suggestions. As for the conference venue, the meeting rooms were comfortable, audiovisuals reliable, the posters easy to see, and there were plenty of Coca Cola products available during the breaks.

Last but not least, I don’t think anyone announced where or when CROI 2014 will take place. Let the speculation begin!

March 5th, 2013

Exploring the Media Fascination with the Baby Cured of HIV

Here’s the story: The mother didn’t know she was HIV positive until delivery, and the baby was found to be infected by both HIV DNA and RNA right at birth. The doctors started combination antiretroviral therapy approximately one day later, essentially as soon as the results came back. There was a good response to treatment, with declining HIV viral loads over the next few weeks that quickly became undetectable.

Successful treatment continued for 18 months, at which time mom and baby were lost to follow-up; the mom stopped the baby’s antiretrovirals. When the two returned to care 5 months later, the baby’s HIV RNA and antibody were both negative — much to the surprise of the doctors. Supplemental testing, using evaluations similar to those done on the Berlin patient, did not yield any evidence of replication-competent virus, and the baby remains off therapy today.

In short, baby cured of HIV. Stop the presses!!! (Do they still say that?) Front page story, New York Times. Look at this Google News Page and the search gadget at the top of this post! Here at CROI, my colleagues and I are all getting e-mails from our friends/family/etc. asking about this “breakthrough.”

And we’re kind of baffled. Because this case will have about as much immediate impact on the HIV epidemic in the United States as the prior cure — that’s right, virtually none. Maybe it will have an impact globally, but that will be a major challenge.

Thinking about it more, however, I understand why this is such compelling news:

- It’s a baby. The media love stories about HIV in babies. The whole “innocent victim” thing is hard to shake.

- It’s a cure. Can’t miss that. And the press is probably hypersensitive about not missing out, since they initially whiffed on reporting the last HIV cure. It was first presented at CROI in 2008 and barely got a peep. Took a resuscitation of the story by the Wall Street Journal and, ultimately, publication in the New England Journal of Medicine for the case to receive major media attention. For the record, rumor has it that a certain highly prestigious medical journal (hint) also initially whiffed on it, rejecting the case report when it was first submitted.

- The public probably doesn’t really understand that HIV in babies is all but 100% preventable. Not emphasized nearly enough in most of the media reports is that the mom didn’t know she was infected until delivery, so she missed out on the key intervention for preventing HIV transmission — treatment of the mom during pregnancy. And since treating pregnant women has long been standard-of-care, pediatric HIV in the United States is vanishing, a real triumph of prevention. Fewer than 200 cases/year in this country, and counting (down).

So what are the practical implications of this case?

First, in developing countries with high HIV prevalence, where perinatal transmission remains a problem, strategies to aggressively treat the newborns of untreated HIV-positive mothers should be implemented pronto. Second, the case will probably teach us a bit more about how we might someday actually cure more than just a single person here and there.

But for now, the headline to this USA Today piece — “Child’s HIV Cure Won’t Mean New Treatments Immediately” — is the understatement of the year.

March 3rd, 2013

It’s Not Safe Sex If You’ve Just Had the Smallpox Vaccine

One of my more memorable teachers used to love warning us about the hazards of sex.

One of my more memorable teachers used to love warning us about the hazards of sex.

No, this wasn’t in my 8th grade health class — this was during my first year of Infectious Diseases fellowship, and the teacher was one of our highly experienced attending physicians, now retired.

To him, sex carried limitless infectious risks. He demonstrated these hazards in lectures that featured an endless series of grisly Kodachromes projected in a dark classroom, explicit images that were not for the faint of heart. Think driver’s ed films, only substitute still shots of diseased genitalia.

Now, mind you, this man was married, and had three children. We ID fellows wondered how — literally — those children found their way to planet Earth given his obvious fear of procreation. We envisioned that they were most likely conceived by two people in hazmat suits, communicating via crackly intercom, with requisite background loud breathing.

Imagine the following verbal (and other) exchange, the voices similar to Darth Vader’s in Star Wars.

Him: Requesting permission for exchange of bodily fluids. Over.

Her: Permission granted. Place liquid in sterile receptacle, and evacuate area immediately. Over.

Him: Objective completed. Evacuating area. Over.

Her: Sperm transport initiated. Over

Then, nine months later, voila, a baby!

All of this came rushing back to me when I read this case report of sexual transmission — twice, no less! — of the vaccinia virus from the small pox vaccine. From the summary in Physician’s First Watch:

One man received smallpox vaccine through the U.S. Department of Defense, but he did not cover the vaccine site as instructed. After intercourse with the vaccinee, a second man was hospitalized for painful perianal rash and upper-lip sore, as well as fever and emesis; he reported having had contact with “moisture” on the vaccinee’s arm. The second man then had intercourse with a third, who was also hospitalized with genital and arm lesions.

Yet another infectious risk of unprotected sex — one not even considered by my fearful ex-attending. And here is an interesting comment from a colleague of mine, someone who specializes in HIV prevention:

What surprised me was that transmission was from an enlisted man to another man who presented with anal lesions and had contacted someone who then got penile lesions. Oh dear! Not what I expected as I began reading these case reports. And what’s with the contact with “moisture” on the arm (that could be anything). Did this rather unusual chain of transmission in these three cases occur among immunocompetent hosts, or was it an outlier series of events related to greater susceptibility conferred by underlying HIV infection?

Good question — the HIV status of only one of these men is reported (he was negative). Regardless, is it time to add vaccinia to the (long) list of potentially sexually transmitted infections? Might be enough to get my former attending back out on the lecture circuit.

February 28th, 2013

Guest Post: CROI at 20 — A Look Back

The inimitable Carlos del Rio looks back at our premier scientific meeting, the annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), which starts this Sunday:

The inimitable Carlos del Rio looks back at our premier scientific meeting, the annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), which starts this Sunday:

CROI, which started as a small national conference held in a hotel in Washington DC, will hold its 20th meeting this year . When CROI first took place, we had just returned from Berlin, and HIV scientists were frustrated because science was not making progress against AIDS. However, during the opening plenary, Robin Weiss of Chester Beatty Laboratories in London reminded us that AIDS would only be conquered though solid science.

How right he was — CROI quickly became the forum where the best science was presented. Over the years we have learned at CROI about ART management going from single to double to triple therapy and about phase I, II, and III studies of novel antiretrovirals such as ABT-378 (lopinavir), BMS-232632 (atazanavir), GW433908 (fosamprenavir), T20 (enfuvirtide), TMC125 (etravirine), TMC114 (darunavir), MK-0518 (raltegravir), GS-9137 (elvitegravir), and TMC278 (rilpivirine). Landmark ACTG and industry clinical trials and studies that have favored earlier initiation of ART — first presented at CROI — have resulted in modification of treatment guidelines. With HIV-infected persons now living longer, conditions such as lipodystrophy, cardiovascular diseases, and bone disorders have presented new challenges, and CROI has become more than a meeting of ID researchers.

While CROI initially had little international focus, the global epidemic is now a critical part of the conference. Results of important trials such as SAPiT and STRIDE have led to changes in national and international treatment guidelines. Prevention was not at first a major focus, but some of the most important biomedical prevention trials have subsequently been featured, with the result that the divide between prevention and treatment is now all but gone. Finally, at last year’s CROI, first steps toward cure were presented, and the gloomy mood of early years has been replaced by one of cautious optimism that the epidemic can be ended. If — or when— that happens, we can be sure that good science was the cornerstone of such accomplishment.

In this table, I’ve highlighted what I think has been the major news from each year’s conference.

Enjoy the trip down memory lane!