An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

January 15th, 2014

Unanswerable Questions in Infectious Diseases: The Abdominal Collection and Duration of Antibiotic Therapy

Each time I attend on the inpatient service, the number of questions for which we just don’t have a definitive answer continues to amaze me. And here’s the most remarkable part — many of them come up all the time!

Each time I attend on the inpatient service, the number of questions for which we just don’t have a definitive answer continues to amaze me. And here’s the most remarkable part — many of them come up all the time!

In that spirit, I will post a series of these quandaries, and you, the brilliant readers, will offer your answers or, barring a definitive answer, your individual approach.

Let’s start with this one:

How long should we continue antibiotics in someone with infected abdominal collection and a percutaneous drain?

You know the situation — peritonitis from perforation, or diverticular abscess, or a surgical mishap, and now the interventional radiologists have kindly placed a drain into the infected collection. (Or, more commonly, multiple drains into the multiple collections.) The patient, once critically ill, is improving — albeit slowly — and the resident, surgical PA, and surgeon all want to know the answer to the above question.

Low grade fevers — 99.5 F or so — continue. There might be an ongoing anastomotic leak, there might not. There is no plan for more surgery. White blood cell count is down from 25K to 15K. Platelets are slowly rising.

Yes, this is a specific variant on the age-old “How long should we treat?” question. I’ve opined on this before, but now we’re getting specific. These IDSA guidelines say “4-7 days,” but that implies rapid source control, no ongoing leak, everything going smoothly.

(And these smooth-sailing cases rarely trigger an ID consult.)

So what do you do in this particular situation? Please vote and comment — especially if you don’t like any of these answers!

January 2nd, 2014

A New Year’s Snowstorm ID Link-o-Rama

Some ID/HIV items jangling around in the inbox, just dying to get out, before they are covered in snow:

Some ID/HIV items jangling around in the inbox, just dying to get out, before they are covered in snow:

- Interesting, balanced piece in the New York Times about the slow uptake for PrEP, in particular among gay men. This caught my eye: “Certainly, fewer people have tried PrEP than many experts had anticipated.” I wonder who those experts were? Seems this always was going to be a relatively niche intervention.

- Fascinating editorial in the latest New England Journal of Medicine about preserving antibiotics, which includes this amazing statistic: Almost 80% of antibiotic use in the United States is for livestock. And here’s a great slide for your next talk on antibiotic resistance. Don’t those cows worry about upsetting their microbiome?

- Speaking of antibiotic resistance, I neglected to highlight this extraordinary CDC report on Antibiotic Resistant Threats when it first came out this year. The top three, with threat levels of “Urgent,” are C. difficile, Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (look at this chilling map), and Drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Sounds about right — but I’d have substituted MRSA for the last one — way greater clinical impact. MRSA’s threat level, by the way, is listed as “Serious.”

- Is some chronic low back pain caused by bacterial infection? According to this paper, and this randomized trial of amox-clav, the answer is clearly yes! An editorial rightly describes the implications of these studies for spine surgeons and pain specialists — never mind patients — as “momentous.” Yes, these are the winners of The Most Surprising Studies in ID, 2013. Confirmation of these findings by other investigators eagerly awaited. (What an understatement.)

- These three deaths from Lyme carditis are most worrisome — the patients were really young (26–38 years old), and though two of three had some pre-existing cardiac disease, they were overall pretty healthy. Fortunately, a review of 20,000 pathology specimens at a tissue bank did not find any additional cases, suggesting that Lyme carditis as a cause of death is rare indeed. Still, wouldn’t it be great if the Lyme vaccine for humans were available again?

- As more HIV drugs become generic, this should mean cost-savings, right? Not always, according to this remarkable (and disheartening) report. Lesson: If you don’t like the price of a generic drug, it pays to shop around for the best price. And if you live near a Costco Pharmacy, give them a try, even if you’re not a member — their pharmacies are available to all, with consistently low prices.

- SPOILER ALERT — if you haven’t seen the movie Philomena, just skip to the trailer below and read no further. But if you’re on the fence, you must see it, since it could have been the best film of 2013 — entertaining, well-acted, funny, heartbreaking. Just great. I cite it here on this site because one major plot turn occurs when the main character’s long-lost son is found to have died of AIDS — and though she is naturally very sad, her response was completely non-judgmental in a very non-Hollywood way. I was expecting the typical moral outrage, and was pleasantly surprised that it never came.

Stay warm, everyone, and Happy New Year!

December 8th, 2013

Simeprevir and (Especially) Sofosbuvir Are Great Leaps Forward — and They Will Cost Plenty

Hepatitis C has been potentially curable for decades, but it’s hardly been easy. “I feel like I’m slowly killing myself,” said one of my patients, memorably, during week 24 of a planned bazillion-week course of interferon-ribavirin. (Actually it was only 48 weeks, but seemed like a bazillion weeks.)

Hepatitis C has been potentially curable for decades, but it’s hardly been easy. “I feel like I’m slowly killing myself,” said one of my patients, memorably, during week 24 of a planned bazillion-week course of interferon-ribavirin. (Actually it was only 48 weeks, but seemed like a bazillion weeks.)

Then in 2011 came the addition of telaprevir or boceprevir to the interferon-ribavirin, which made a cure more likely, but the treatment even worse. Rashes. Need for fatty meals. Tons of pills. Taste disturbance. Anal discomfort. (“Like shitting glass,” another memorable quote.) Anemia. And for the providers, having to manage these side effects and the complex “response-guided therapy” algorithms was no picnic.

Now, with the approval of simeprevir in November and in particular sofosbuvir Friday, HCV cure just got a whole lot easier. Both are one pill a day. Both have far fewer side effects than any existing HCV drug. Sofosbuvir adds the benefit of having almost zero important drug-drug interactions. (Simeprevir has many.)

The main problem with these new treatments is, frankly, their cost. They are very expensive — 12 weeks of simeprevir will be $65,000, of sofosbuvir $80,000. These costs are offset somewhat by reduced need for monitoring with safer therapies, a shorter course of interferon and ribavirin (if you go that route), and presumably down the road, prevented cases of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver transplantation.

And of course, few individuals will actually pay full price out of pocket for these treatments, just like few actually pay for their MRIs or their angioplasties or their stay in the ICU. Treating HCV is not like cosmetic surgery; it’s potentially lifesaving. And as with other expensive but lifesaving treatments, we’re hoping there will be generous patient-assistance programs for those who can’t pay.

But for those without coverage, people in other countries, or those charged with managing pharmacy budgets, this cost is a major hurdle.

All of which leaves me thinking that as of December 8, 2013, these are the best options for genotype 1 HCV infection (cost estimates approximate):

- Simeprevir + sofosbuvir for 12 weeks. PROS: More than 90% cure rate in the COSMOS study. Two pills once daily (it’s amazing even to write that.) CONS: The COSMOS study was very small. Simeprevir can lead to photosensitivity and has many drug-drug interactions. The Q80K polymorphism may reduce response to simeprevir. This regimen is not “FDA approved.” Cost = $145,000.

- Sofosbuvir + ribavirin for 24 weeks. PROS: Cured 76% of HIV/HCV co-infected patients in the PHOTON-1 study. May well do better in HCV mono-infected. Regimen is “FDA approved” for interferon-ineligible patients, which could help get insurance coverage. CONS. Ribavirin, and all its side effects. 24 weeks seems long compared to 12 weeks. Response rate is lower than other options listed here, which would require re-treatment. Cost (not including ribavirin) = $160,000.

- Sofosbuvir + interferon + ribavirin for 12 weeks: PROS: 90% cure rate in the NEUTRINO study. Only 12 weeks of interferon and ribavirin. Cost = $90,000. CONS: Interferon. Ribavirin. Enough said.

All are a lot better than what we had just last week. All of them contain sofosbuvir. And all are expensive.

November 30th, 2013

Five ID/HIV Things to Be Grateful for This Holiday Season

I was speaking with a British colleague the other day, and she was remarking how jealous she was that we get a Thanksgiving holiday each year. Starting with a long whine (or moan, as they would say) about the pressures, commercialization, cost, and religious aspects of Christmas, she then went on about how perfect Thanksgiving seems from her outsider perspective.

I was speaking with a British colleague the other day, and she was remarking how jealous she was that we get a Thanksgiving holiday each year. Starting with a long whine (or moan, as they would say) about the pressures, commercialization, cost, and religious aspects of Christmas, she then went on about how perfect Thanksgiving seems from her outsider perspective.

“What’s not to like? A big pot-luck dinner. Family and friends get together. No presents. A four-day weekend. And the sentiment of gratitude is so lovely.”

(That’s another one of their words — “lovely.”)

Can’t say I disagree, so in that spirit, here’s a quick list of five things from our little ID/HIV worlds to be grateful for, in no particular order:

- Vaccines. Did you see this paper in the New England Journal of Medicine? By conservative estimates, 75 million to 106 million cases of polio, measles, rubella, mumps, hepatitis A, diphtheria, and pertussis prevented by the vaccines in the United States alone. Add to this hepatitis B, H. flu, rotavirus, varicella, etc., along with the global effect of preventing all these infections, and the impact of vaccines on public and personal health cannot be overstated.

- Antiretroviral therapy. For those of us who have been doing this HIV treatment thing for a while, the movie “Dallas Buyers Club” quickly takes us back to a time that is almost unimaginable today — before effective antiretroviral therapy, before opportunistic infection prophylaxis, to a time when the clinical and research medical establishment was often at odds with the very people we were supposed to help, the people with AIDS. Sure, some of the medical details in the film are screwy — ddC a better treatment than AZT? — but it’s highly recommended nonetheless, with an unbelievably great performance by Matthew McConaughey, as you can see in the trailer below. Good to be reminded, every so often, just how transformed HIV disease is by current therapy.

- Doxycycline. How much do we ID doctors love you? Let me count the ways: Lyme disease, MRSA, anaplasmosis, ehrlichiosis, community-acquired pneumonia, urethritis, syphilis, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, malaria prevention, anthrax prophylaxis, pelvic inflammatory disease, brucellosis, wolbachia (that last one a trivia question for ID fellows)… And not only that, the drug is relatively safe (just don’t take it before lying down) and inexpensive (this year a bit less so, unfortunately). To continue the British theme, if you want to know every ID doctor’s “Desert Island Drug”, this is it — just be sure to bring the sunscreen. “Doxy,” thank you for being you — we are very, very grateful.

- AIDS Drug Assistance Programs (ADAPs). Here’s a challenging problem for the healthcare “system” (ha): A disease that is fatal, transmissible, stigmatized, and disproportionately targets the poor. Oh, and treatment is extremely effective, but also quite expensive. Problem? What problem? For HIV, we have a national program, administered by the states, that virtually guarantees everyone (with few exceptions) lifesaving antiretroviral therapy, regardless of their ability to pay — yes, ADAPs are truly miraculous. Sure, we worry about waiting lists and strained budgets (especially in the Southeast), but the number of people denied HIV therapy in the United States today remains small indeed. Who knows what form ADAPs will be in over the next few years with institution of the Affordable Care Act, but let’s hope this remarkable state of affairs is preserved.

- Microbiome and Resistance Awareness. Every healthcare provider has vast experience with the “green phlegm” patient encounter. It goes something like this: Patient is suffering from a prolonged cough, or runny nose, or some other respiratory symptom, and he/she keeps telling you that they have “green phlegm.” This term, you see, has long been a code for, “I need an antibiotic.” Never mind that the color of these secretions says little about whether the infection is bacterial or viral, somehow the public perception was that the only way to return to health, to eliminate the nasty green goo, was to start an antibiotic. Yet over the past few years, a Gladwellian Tipping Point has been passed: We still have the green phlegm conversations — isn’t being a doctor/nurse wonderful? — but for various reasons there are now lots of people out there who would prefer not to take an antibiotic if at all possible. Microbiome (all those good bacteria) awareness? Fear of antibiotic resistance? A friend/family member with C diff? Probably all of the above, and it couldn’t be more sensible, since of course all antibiotics can be harmful (even doxycycline).

What are you grateful for these days?

November 27th, 2013

Gynecologists May Treat Men After All

Good news here for gynecologists who screen men for anal cancer:

A professional group that certifies obstetrician-gynecologists reversed an earlier directive and said on Tuesday that its members were permitted to treat male patients for sexually transmitted infections and to screen men for anal cancer…

It’s always impressive when a group swiftly reverses what is widely perceived to be a wrong decision, so praise to the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology for their flexibility.

Now as for obstetricians — sticking with a females-only policy makes all kinds of sense. Just ask the former governor of California:

November 23rd, 2013

OB/GYN Board Says Their Docs May Only Treat Women

Here’s a surprising move: The American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology has decreed that gynecologists may only treat women. From the New York Times coverage:

In September, the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology insisted that its members treat only women, with few exceptions, and identified the procedure [high-resolution anoscopy] in which Dr. Stier has expertise as one that gynecologists are not allowed to perform on men. Doctors cannot ignore such directives from a specialty board, because most need certification to keep their jobs.

Many ID/HIV specialists will immediately see this move as strange, and potentially quite disruptive. At one of my practice sites, we refer all our HIV-positive patients who have anal dysplasia — men, mostly, but also women — to gynecologists who are skilled in high-resolution anoscopy, a procedure similar to colposcopy. Plus, on a national level, there’s an important ongoing clinical study that is evaluating whether this screening strategy prevents anal cancer; at least some of the co-investigators are gynecologists.

(FYI, we’ve been wondering about the efficacy of this in screening for anal cancer prevention for years.)

It’s also a strange move because, frankly, no such other restriction exists for any specialty — it’s tough even to envision such a thing, unless there’s a dermatologist somewhere out there who will only treat patients whose last names start with the letters Z, I, and T.

With the caveat that as an ID specialist, I’m far from the center of this debate, this action by the OB/GYN Board seems extreme. It’s doubtful that the relatively small number of gynecologists who perform this procedure on men will distract them sufficiently to negatively impact the health of women.

Perhaps it’s a “waiting room” phenomenon? My local expert says that women have grown comfortable seeing only other women at gynecology practices, and might find it strange to share the waiting room space with men. And we men do have a tendency to yuck things up — “boy slime,” is how my wife described the effect of sharing bathrooms with guys during college.

But she offers this logical solution: Let the gynecologists who are currently providing this clinical service and participating in research continue doing so. A statement from the board that such treatment is discouraged (but not forbidden) will certainly decrease the number of new gynecologists taking male referrals.

November 16th, 2013

Janssen to Stop Offering “Virtual Phenotype” Testing, and Musings on Progress

Head over to this page from Janssen Diagnostics, and you’ll receive this little pop-up message:

Must say it’s in some ways sad to see it go — in my opinion the nifty work they did correlating genotype results with their database of phenotypes gave the clearest representation of what a genotype actually means. If you didn’t want to order both genotype and phenotype simultaneously — which was expensive and took weeks to come back from the lab — vircoTYPE was was the most efficient way to get information on complex resistance patterns. Sure, one could quibble about methodology and validation of the test, but it was remarkable indeed to send a genotype and get back results estimating fold-change, upper and lower cut-offs, full and partial activity — and virus clade, just for kicks.

But am I surprised it’s disappearing? Not if you think about it for a moment. As is plainly obvious to anyone doing HIV care, the incidence of new patients with the sort of HIV drug resistance for which the test was developed has plummeted. There simply aren’t many new patients out there who have multiple mutations, especially in the PI-drug class, and who will need the computational black-box firepower provided by a vircoTYPE. A regular genotype does just fine for those who are newly diagnosed, or have virologic failure on a first-line regimen due to poor adherence.

What about the existing patients with this sort of resistance? Most are virologically suppressed right now, and hence don’t need resistance tests anymore.

And in a nice irony, it’s in part the antiretrovirals made by the therapeutics branch of this company — darunavir in particular, etravirine as well — that have made the vircoTYPE obsolete. These two drugs, plus raltegravir, mean that most people with resistance are suppressed.

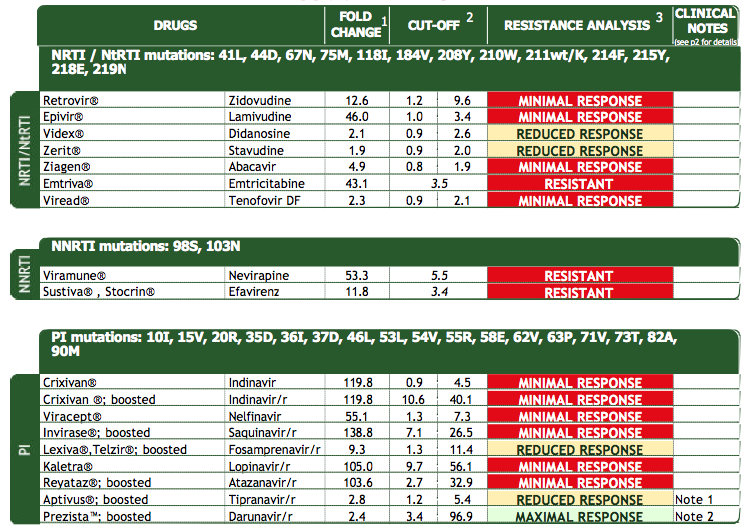

So for posterity’s sake, here’s a “beautiful” (what a nerdy thing to write) vircoTYPE from one of those patients, the test obtained in the late 2000s:

His current situation? Virologically suppressed on darunavir, etravirine, raltegravir, of course.

November 13th, 2013

How Doctors, Nurses, and Other Medical Providers Spend Their Free Time

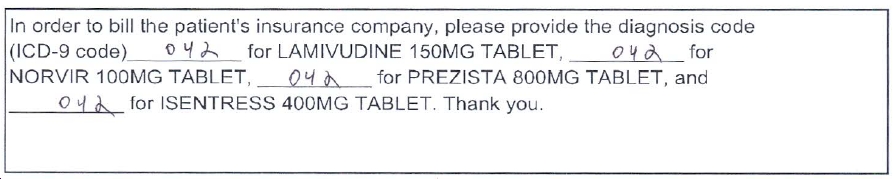

More absurd paperwork follies, this time from our friends at a mail-order pharmacy:

Here, confronted with the challenge of refilling a patient’s HIV medications — which for the record he has been receiving unchanged for over 3 years — the pharmacy decides for the first time to reject the request and send the prescription back to us (by fax of course), including a cover sheet that reads, “Required Information Missing — Pls complete ASAP.”

(No doubt they saved plenty of time by omitting 3 letters in the word “please.”)

Is there a problem with the dose? The instructions? Is there a concerning drug-drug interaction? Did we forget a key component of the regimen?

No, no, no, and no. The problem is that each medication now requires its own “Diagnosis Code,” those inscrutable numbers that already bedevil our billing sheets. Otherwise the pharmacy won’t get paid.

Of course you could ask what else could darunavir, ritonavir, raltegravir, and lamivudine be used for besides HIV, or “042” in ICD-9-ese. Or ask why suddenly now they require the code, since they never did in the past — it’s not as if the indications for these drugs have somehow changed.

And does someone really check to see that the diagnosis code matches the medication? Just to make sure, next time I need to refill HIV meds at this particular pharmacy, I plan to put 380.4 down — that’s “ceruminosis,” or ear wax, in case you’re wondering.

I’ll let you know what happens.

November 6th, 2013

SINGLE Study Underscores Waning of the Efavirenz Era — But Probably Just in the USA

In today’s New England Journal of Medicine, the SINGLE study finally makes its appearance “in print.” (The study results were first presented over a year ago.) The highlights:

In today’s New England Journal of Medicine, the SINGLE study finally makes its appearance “in print.” (The study results were first presented over a year ago.) The highlights:

- SINGLE was a double-blind, randomized clinical trial comparing abacavir/lamivudine plus dolutegravir to tenofovir/FTC/efavirenz in 833 treatment-naive study subjects. That’s right, three different drugs in each arm — you don’t see that much in HIV clinical trials these days.

- At 48 weeks, 88% of the dolutegravir group and 81% of the efavirenz group had HIV RNA < 50, making the dolutegravir arm superior. CD4 response also significantly better.

- The difference between the two arms was driven by more study drug discontinuations in those receiving the EFV regimen; virologic responses were similar.

- There was no resistance detected among those with virologic failure on dolutegravir.

Setting aside the NRTIs for now, we must again note that this is the very first time anything has beaten an EFV-based regimen, and it’s not for lack of trying. Starting with its surprising defeat of indinavir way back in the 1990s, efavirenz has subsequently bested fosamprenavir, lopinavir/r, nevirapine, nelfinavir, and abacavir.

(And let’s not forget once-daily soft-gel saquinavir/r. That’s nine pills/day just for the saquinavir/ritonavir, yikes.)

The most any challenger could do was tie — see atazanavir/r, raltegravir, elvitegravir/cobicistat — or, in the case of rilpivirine, offset lesser antiviral activity with a better tolerability profile. In short, up until the SINGLE study, one could argue that EFV-based treatments — especially TDF/FTC/EFV — represented the gold standard against which all other regimens must compete.

Has that now changed? I think it has.

Note that these SINGLE study results come out just as other data and clinical experiences have less forcefully nudged efavirenz off its perch on top of the HIV treatment world. Want a single pill for HIV treatment? There are now two other options, TDF/FTC/rilpivirine and TDF/FTC/elvitegravir/cobicistat, both of which have significantly lower rates of CNS side effects and rash; abacavir/lamivudine/dolutegravir is on its way as another option.

Furthermore, those efavirenz CNS side effects may not be so benign — a study presented at this year’s IDWeek (disclosure: I’m a co-investigator) found that those randomized to efavirenz had twice as high a rate of suicidal ideation as in the non-efavirenz treatments. Yes, the absolute risk was low, but this is a much more serious adverse effect than the famous “vivid dreams” reported so frequently by those receiving efavirenz.

So what about the rest of the world? The World Health Organization Guidelines, updated just this summer, have this to say about initial regimens:

Once-daily regimens comprising a non-thymidine NRTI backbone (TDF + FTC or TDF + 3TC) and one NNRTI (EFV) are maintained as the preferred choices in adults, adolescents and children older than three years … TDF + 3TC (or FTC) + EFV as a fixed-dose combination is recommended as the preferred option to initiate ART

Which means we are far from seeing the end of the efavirenz era globally, where the drug is widely (and accurately) viewed as effective, inexpensive, and relatively well-tolerated. All good things.

Just not quite good enough anymore, given what’s out there as competition.

Your thoughts?