An ongoing dialogue on HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases,

September 3rd, 2014

How to Choose a Case for ID Case Conference

As August becomes September, ID fellows across the land are becoming increasingly skilled, heading rapidly upwards on that steep learning curve that is the first year of fellowship. With one-sixth of the year already in the books, it’s a wonderful thing to see.

As August becomes September, ID fellows across the land are becoming increasingly skilled, heading rapidly upwards on that steep learning curve that is the first year of fellowship. With one-sixth of the year already in the books, it’s a wonderful thing to see.

One potential downside to this accumulating knowledge, however, is that they start to become familiar — they would say overly familiar — with the cases that make up the bread and butter of our field. “Another liver abscess? Big deal. I’ll get excited when the abscess is drained, and the cytology shows hooklets of Echinococcus — now that’s a case!”

(No one actually said that. It was a hypothetical paraphrase.)

Which is why in a month or two, they will start to wonder if they have any patients on their service that are case conference-worthy.

But the following guide will act as a reminder that yes, the ID service sees the most interesting cases in the hospital, and there is always something worth presenting at weekly case conference. Let’s take look at the options:

- The Amazing Case. These are obvious, so I will not belabor it, but typically they involve a rarely seen pathogen that somehow found its way to your hospital or clinic. Example: Just back from safari, a man came to the hospital with fever and headache — and lo, he had trypanosomes swimming around his blood smear. Needless to say, the ID fellow taking care of this man with African trypanosomiasis (a.k.a, “African Sleeping Sickness”) had no trouble selecting it for conference. That one was easy, so let’s move on.

- The Textbook Case. Every so often a patient has an illness that has not just a few, but every characteristic feature of a specific clinical syndrome — it’s as if they read a medical textbook before going to the doctor. Such cases have tremendous educational value, especially for residents and medical students — but really, who among us couldn’t use a refresher on what makes a case a “classic”? Example: The guy with several weeks of fatigue, anorexia, and low-grade fevers, physical exam with all the peripheral stigmata of endocarditis (Roth’s spots, Osler’s nodes, Janeway lesions — can you keep them straight?), a characteristic heart murmur, and a 1.5 mobile aortic valvular vegetation on the cardiac ECHO. Classic.

- The Funny Bug, Especially if in a Funny Place Case. Certain unusual microorganisms — funny bugs — can be conference-worthy on their own, especially if they have a great name (Staphylococcus lugdunensis) and/or a strong epidemiologic association (Capnocytophaga canimorsus = dogs, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae = lobsters, among other creatures). Now throw that funny bug into a funny (unusual) anatomic site, and bingo, you’ve got your case — even if it’s hardly a common manifestation of this infection. Example: A 31-year-old pregnant woman was admitted with abdominal pain and fever — ultimate diagnosis? Acute endometritis and bacteremia from Pasteurella multocida. Of course.

- The Now Quite Rare but Previously Very Common Case. Progress in vaccines has made certain conditions that were once standard business now quite unusual. As an example, I can count the number of cases of adult measles I’ve seen on one hand, or more precisely, on one finger. As a result, these cases are virtually always conference worthy, plus they give our more senior clinicians (ahem) a chance to wax eloquently about the bad old days. Examples: Virtually any vaccine-preventable illness (measles, mumps, Haemophilus influenzae invasive disease, even varicella). Bonus points for a case of rheumatic fever or late-onset neurosyphilis — not vaccine-preventable, but you get my drift.

- The Amazing New or Incredibly Confusing Diagnostic Test Case. Just the other day, a colleague from another hospital emailed me with excitement about a case of malaria. It wasn’t the case that was unusual — returning traveler from Africa, fever, etc. — but the fact that his hospital just got the Binax malaria rapid test, and he got the positive result back almost immediately. He was so excited he even took a picture of the positive test with his phone, sending it along with the email. Other examples: The first time you diagnose PCP with blood beta-glucan and or PCR. Or a case that makes you struggle through the C. diff testing quagmire. Or one that forces you to interpret the results of an EBV antibody panel. Someone with a dozen different Lyme tests — with one of twelve positive. (Ok, maybe not that last one.)

- The “Wow” Image Case. Way back in prehistoric times — meaning during my ID fellowship — one of our responsibilities as an ID fellow was to gather the relevant x-rays on our cases, not only for rounds, but also for case conference. It is no understatement that this was a huge challenge — these films were frequently scattered hither and yon throughout the various hospital buildings, so much so that we suspected that the place labeled “Radiology Film Library” was just a front for the hospital casino. And there seemed to be some hospital rule that all interesting brain CTs/MRIs were kept under the call-room bed of the neurosurgical chief resident. Today we have electronic access to all the images, plus everyone is carrying a camera, so we have this great opportunity to display these during conference. Examples: The initial rash of necrotizing fasciitis. Then the operative findings. The volleyball-sized tubo-ovarian abscess in the pelvis on CT scan, prior to drainage. (“Wow,” everyone will say.) The botfly removal (caution, observe at your own risk). You get the picture (ha).

- The Public Health Case. Let’s just imagine that someone shows up in your emergency department from Liberia/Sierra Leone/Guinea/Nigeria/Senegal. Never mind that they came in for a sprained ankle, someone is going to bring up the possibility of Ebola — especially when, on further questioning, the ankle person from Western Africa admits that 1) yes, they just visited family at home, and 2) yes, they too are worried about it; wouldn’t you be, especially since there’s a bit of headache/joint pain/fever. Since a sprained ankle and Ebola are hardly mutually exclusive, we’re talking prime conference material as soon as you get the consult — golden! Other examples: Any healthcare worker with tuberculosis. Or a restaurant worker with salmonella. You get the idea.

- The Management Dilemma Case. Despite our thick textbooks and nearly the entire universe of published papers available instantly on line, there’s a ton we still don’t know. I’ve written about a bunch of these clinical situations (here’s the list), and you can tell from the poll results that there really is no right answer — but that doesn’t stop people from having opinions. Another example: 60-year-old woman, professional cellist, has bronchiectasis and slightly worsening cough; a sputum culture is positive for M. abscessus, resistant (as usual) to all oral agents — she can’t imagine a life without playing the cello, and travels frequently. Should she be treated? If so, with what?

- The Everyone Else Was Messing Up Until We Came In and Saved the Day Case. All doctors love these EEWMUUWCIASTD cases, and they should never be underestimated as high-value material for case conference. In surgical conferences, they invariably present a patient languishing on the medical wards with abdominal pain, until “we took him to the OR and saved his life.” In ID conference, it takes a different form because we do no procedures. It usually involves some perfectly obvious (to us) historical detail that bingo, cracks a mystery case wide open — e.g., “So we simply asked her where she grew up and went to college, and when she told us Tennessee, we knew it was likely histoplasmosis”; or “They thought it was a simple community-acquired pneumonia, but we found out he had a twenty-pound weight loss, hemoptysis, and a history of an untreated positive PPD”; or “All someone had to do was ask her in Spanish/Vietnamese/Chinese/Haitian Creole what was wrong with her, and she told us”; or “He works as a touring semiprofessional golfer, had just returned from Mexico, and mentioned that he licks his golf balls before each drive for good luck.” These EEWMUUWCIASTD cases are tremendously gratifying — they reinforce the fact that we are the smartest doctors in the hospital, plus they make us feel better about the inverse correlation of intelligence with annual income.

I hope the above examples are a reminder that not all ID consults are decubitus ulcers and ICU fevers.

And if I left out a category, please let me know!

August 24th, 2014

Combination ABC/3TC/DTG Approved — Fourth One Pill a Day HIV Treatment

As expected, there’s a new single pill regimen for HIV, this one containing abacavir (ABC)/lamivudine (3TC)/dolutegravir (DTG), and it’s called Triumeq.

As expected, there’s a new single pill regimen for HIV, this one containing abacavir (ABC)/lamivudine (3TC)/dolutegravir (DTG), and it’s called Triumeq.

(Where oh where do companies get these names?)

A few thoughts/comments:

- The most important study for this combination was the SINGLE study, which showed that ABC/3TC + DTG (given as two pills) was superior to TDF/FTC/EFV (given as one), the difference based primarily on tolerability advantage of the former. It was a novel double-blind study, as all three drugs were different in each treatment arm.

- Another benefit DTG-based regimens — whether given with ABC/3TC or TDF/FTC as separate pills — is that to date, no treatment-naive patient with virologic failure has developed resistance to DTG. I suspect it will happen one of these days, but the data thus far suggest at the very least DTG resistance will be a rare event.

- Needless to say, but will say it anyway for emphasis, all patients starting this regimen will need to be tested for HLA-B*5701 and found to be negative. Wonder if pharmacies will enforce this, or whether it will be left up to the prescribers. Here’s the landmark study that proved this testing essentially excludes severe hypersensitivity to ABC, quite an amazing story in pharmacogenomics.

- An unresolved question is whether ABC is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. This FDA meta analysis of randomized clinical trials didn’t think so, but around half of the observational studies did, including the updated DAD study. NA-ACCORD data will be of great interest, whenever they appear.

- As of Sunday, August 24, the price of ABC/3TC/DTG is not known (at least to me) — and it could be a real game changer, since both ABC and 3TC are already generic. Says Ben Young over on TheBody: “If ViiV Healthcare manages to set the price of Triumeq in accordance with the generic status of abacavir and lamivudine, the cost should be substantially lower than the price of the other single-tablet regimens that contain all on-patent components.” Yep.

- I suspect people will call it “Trii” (rhymes with “Cy”, as in “Cy Young”) for a while, just like they called TDF/FTC/EVG/COBI “Quad”.

So what are some upcoming single-tablet regimens? Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) with FTC/EVG/COBI. TAF/FTC/DRV/COBI. DTG/rilpivirine. And inevitably, generic TDF/3TC/EFV, which is widely available globally.

Regardless, sure beats the old days.

August 16th, 2014

Dietary Advice From Your Friendly ID Doc: Don’t Eat Garden Slugs

From the pages of Open Forum Infectious Diseases, comes this cautionary case report:

From the pages of Open Forum Infectious Diseases, comes this cautionary case report:

Toxocariasis After Slug Ingestion Characterized by Severe Neurologic, Ocular, and Pulmonary Involvement

I encourage you to read the full paper, but the short story is that a previously healthy 71-year-old man was admitted to a hospital in France with fever, cough, headaches, confusion, and eosinophilia. A comprehensive (that’s an understatement) work-up found elevated antibody levels to Toxocara canis, otherwise known as the dog roundworm.

But the case truly hinges on this sensational sentence.

One month later, a reassessment of the case history revealed a long-standing daily intake of 2 or 3 raw local slugs for alternative therapy of gastroesophageal reflux; this information prompted us to perform further investigations.

Vive La France!

And oh yeah, ID doctors take the best medical histories.

August 10th, 2014

Waiting (and Preparing) for Ebola

For Infectious Diseases doctors, there’s a certain life cycle to the big ID topics that make their way to the lay press, and it’s playing out right now big time with the terrible Ebola outbreak in Western Africa. It goes like this:

For Infectious Diseases doctors, there’s a certain life cycle to the big ID topics that make their way to the lay press, and it’s playing out right now big time with the terrible Ebola outbreak in Western Africa. It goes like this:

- Someone reports an outbreak in a venue like ProMED.

- Almost synchronously, it is covered by the news.

- Depending on the severity of the outbreak and the Gladwellian “stickiness factor,” it then becomes well known outside of the ID community. And boy, does Ebola have plenty of stickiness — much more than chikungunya or listeria in fruit, for example, to cite some recent entities that grabbed a fair amount of attention.

- Suddenly everyone wants to talk to you, Dr. ID Person, about it — the orthopedic surgeon (two of them mentioned Ebola to me last week!), the ICU nurse, the people you play canasta with (I don’t play canasta, just assuming), your Aunt Becky (I do have an Aunt Becky), and even complete strangers who, in the course of serving you food at a restaurant or fixing your car or changing the grip on your badminton racket, find out that you’re an ID doctor. You’re the expert, after all.

The problem is that going from Item #1 to Item #4 can happen awfully fast. And because these newsworthy outbreaks frequently haven’t played out before — otherwise they’d be less newsworthy — it’s virtually guaranteed you are not in fact an expert. At least not yet.

Which sends you (and all of us, trust me) scurrying to the great big web in the sky for some intense reading on the disease du jour.

So for the ID doctors reading this out there, please share your best sources for the latest in Ebola news and information. CDC, of course, and the aforementioned ProMED, the prescient HealthMap and if you want to drink from a fire hose of lay coverage, the Google news feed — where else?

And for non-ID readers, cut your ID docs a little slack if we don’t instantly know the answer to your Ebola questions. We’re working on it!

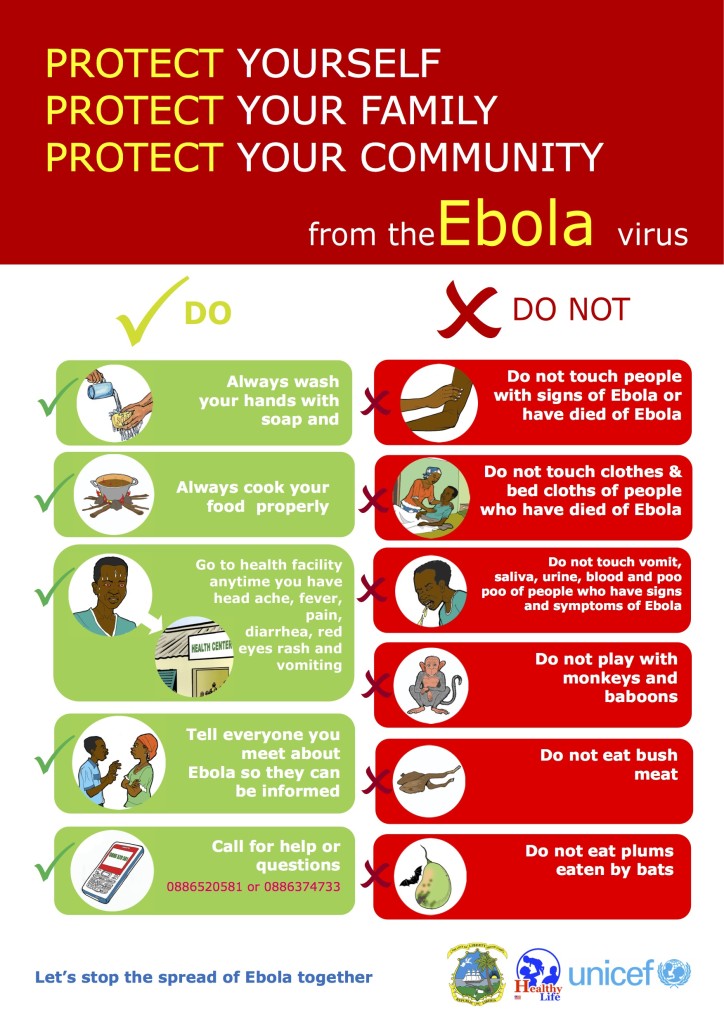

In the meantime, please don’t eat plums eaten by bats.

July 31st, 2014

Simeprevir, Sofosbuvir, and the Limitations of the COSMOS

These are exciting times for hepatitis C treatment, as the approval of simeprevir and sofosbuvir in late 2013 have made curing this disease a whole lot easier.

These are exciting times for hepatitis C treatment, as the approval of simeprevir and sofosbuvir in late 2013 have made curing this disease a whole lot easier.

Since that sentence barely conveys the transformative nature of this medical advance, allow me this tortured analogy: Before simeprevir and sofosbuvir, curing hepatitis C was like making a transatlantic journey by ship, and you had to stay in steerage — always a long and painful trip, but you’d get there if you could stand it. Now the cure is like a business-class flight — much shorter, safer, and more comfortable, but you just have to have the resources to pay for it.

But our treatments are not perfect. I was reminded of this fact when someone treated with simeprevir and sofosbuvir — or “SIM-SOF” as it’s commonly abbreviated — just relapsed a month after finishing 12 glorious, side-effect–free weeks of treatment.

In hindsight you could perhaps have predicted that this patient — or this type of patient — would be a treatment failure on these new drugs. There was prior treatment failure on interferon/ribavirin; he has genotype 1a (and hence probably Q80K, didn’t test for it); he’s overweight; he has several other medical problems, including diabetes.

And, probably of greatest importance, he has cirrhosis, diagnosed by liver biopsy several years ago.

The treatment failure sent me scurrying over to the reason we use this combination anyway — the excellent HCV treatment guidelines and the remarkable COSMOS study (just published in the Lancet) of simeprevir and sofosbuvir, with and without ribavirin, in patients with HCV genotype 1.

Here’s what recommended in the guidelines for patients who have failed prior treatment:

Daily sofosbuvir (400 mg) plus simeprevir (150 mg), with or without weight-based RBV (1000 mg [75 kg]) for 12 weeks is recommended for retreatment of HCV genotype 1 infection, regardless of subtype or IFN eligibility.

And here are the relevant data cited:

Among those null responders with a Metavir fibrosis stage of 3 or 4 (n=47) who received 12 weeks of sofosbuvir and simeprevir, SVR4 was observed in 14 (93%) of 15 patients in the ribavirin-containing arm and 100% (all 7 participants) in the RBV-free arm.

A few things stand out from reviewing the study and the guidelines, aside from the high response rate:

- The sample size in the COSMOS study was small.

- The number with actual cirrhosis was even smaller, as they combined stages Metavir 3 and 4.

- The number with actual cirrhosis who did not receive ribavirin and received only 12 weeks of treatment was smaller still.

- And did I mention — the sample size in this study was small?

The reason I’m harping on the sample size is a lesson taught early in every Stats 101 course — namely, that a small sample size means that the outcome will not be very precise, with lots of potential wobble around the results.

The most recent data presentation of the COSMOS study allows us to drill down a bit more on the data. There were 7 patients — just 7 — with cirrhosis who received only simeprevir and sofosbuvir for 12 weeks. 6 out 7 were cured (SVR 12), for a response rate of 86%.

And the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval for this proportion? 60%, at least according to this web gizmo that does the math for us, if I’ve chosen the right “equation”. So the occurrence of relapses should not be a huge surprise, despite the > 90% response rate for the study overall.

Some take-home lessons:

- Unlike the real thing, the COSMOS study is very small. (There’s a larger study of this combination ongoing.)

- This small sample size means we can’t predict response rates with much accuracy, especially in the hardest to treat patients who were not heavily represented in the study.

- SIM-SOF (note it’s rarely “SOF-SIM”) is still a great advance in HCV treatment, but treatment failures will happen.

So what to do next? The good news is that resistance to sofosbuvir is rare even in treatment failures, and that the HCV treatment cosmos is about to get bigger — the next class of drugs (NS5A inhibitors) is on the way soon, and the data on sofosbuvir plus ledipasvir or daclatasvir look very promising.

A reason for optimism even for those for whom SIM-SOF didn’t do the trick.

July 30th, 2014

Hepatitis Day “Celebration” and a Reminder

July 28 is “World Hepatitis Day” (how do they choose the dates for these things?), and I wrote a bit over on the Oxford University Press site on the incredible progress we’ve made already — with more to come.

Definitely plenty of reasons to celebrate — safe and effective immunizations for hepatitis A and B, treatment (non-curative) for hepatitis B, and astounding therapies now for HCV. Still, given the global magnitude of these infections, and the problems of access, there is plenty of work to be done to get people immunized, diagnosed, referred, and treated.

Enjoy the tune.

July 27th, 2014

Really Rapid Review — AIDS 2014, Melbourne

![]() For the second time — the first time was in Sydney, 2007 — the annual “summer” international AIDS conference took place in Australia, this time in Melbourne way down in the southern part of the country. I’ll note again how the crash of Malaysia Airlines flight MH-17 cast a sad note over the opening sessions, and throughout the conference many people gave moving tributes to friend and colleague Joep Lange.

For the second time — the first time was in Sydney, 2007 — the annual “summer” international AIDS conference took place in Australia, this time in Melbourne way down in the southern part of the country. I’ll note again how the crash of Malaysia Airlines flight MH-17 cast a sad note over the opening sessions, and throughout the conference many people gave moving tributes to friend and colleague Joep Lange.

This being the larger of the two international meetings, there was plenty of non-medical, non-scientific content, all of which I’ll completely pass over in this Really Rapid Review©.

(Except to say that Bill Clinton and security entourage walked right past me — he waved hello, though clearly not to me personally.)

With the usual up-front apologies for inadvertently omitting something important, off we go.

- When given with darunavir/ritonavir, maraviroc was inferior to TDF/FTC for initial therapy. We knew this already from the press release last year, but this was the first time we’ve seen the data. Failure rates particularly high with lower CD4 cell counts. Interesting conference dynamic when the presenting author was asked about whether the dose of maraviroc (150 mg mg daily) was too low — he responded rapid-fire with around 5 studies justifying the dose, quite a performance.

- As maintenance therapy, atazanavir/ritonavir plus lamivudine (two drugs) was non-inferior to atazanavir/ritonavir plus 2 NRTIs (three drugs). As with the GARDEL study of LPV/r + 3TC, these results are still more evidence of the magic of 3TC/FTC. Study is called “SALT” — can you guess what this stands for?

- As maintenance therapy, lopinavir/ritonavir plus lamivudine (two drugs) was non-inferior to lopinavir/ritonavir plus 2 NRTIs (three drugs). Again … magic of 3TC/FTC! And this one was called “OLE” — another clever title, please guess the origin.

- Given the results of the above three studies, perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that for virologically suppressed patients, raltegravir plus ATV/r was clearly worse than ATV/r plus 2 NRTIs — the study was stopped by the DSMB for more virologic failures in the experimental arm. What’s causing the underperformance of these two drug regimens that don’t have 3TC/FTC? To quote my friend Joel Gallant, “the only good nuke-sparing regimens contain a nuke.” (When you steal a line that good, you must give credit.)

- The SECOND LINE study found after failing 2NRTIs/NNRTI, second-line treatment with lopinavir/r with either raltegravir (two new drugs) or NRTIs (one new drug plus recycled but still partially active drugs) were non-inferior. In this resistance analysis of the study, having more resistance at study entry lead to a higher likelihood of treatment success. A paradox? Not really, this has been seen before — patients with the worst adherence have the least resistance, hence they do poorly on their next regimens too.

- The SAILING study showed that dolutegravir was superior to raltegravir in treatment experienced patients, and this detailed resistance analysis found that the difference was quite pronounced in those treated only with NRTIs. 0/32 receiving DTG plus NRTIs failed treatment, vs 7/32 for RAL plus NRTIs; for M184V +/- thymidine-associated mutations, there 0/13 DTG vs 4/12 RAL failures.

- In this large analysis of a Spanish treatment cohort, HIV RNA between 20-50 cop/mL did not increase the risk of treatment failure compared to those with HIV RNA < 20 cop/mL. Reassuring, because we don’t know how to manage those patients anyway!

- In an observational Canadian cohort study, patients who switched therapy while virologically suppressed had significantly greater risk of failure than those who didn’t switch. Not surprisingly, the switchers vs non-switchers differed substantially — enough so that this study was this meeting’s winner of the “Unmeasured Confounding Influenced Outcome” award, a limitation the presenter acknowledged.

- How often should we be measuring viral loads in our stable suppressed patients? In this HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS) analysis, virologic suppression rates were similar between those who did and did not have HIV RNA measured more than twice a year. Could save a boatload of money if the frequency of these tests could be reduced in selected stable patients.

- What are some of the predictors of prescribing guidelines-concordant HIV treatment in the USA? Glad to see that being an ID specialist was one of them! (Love the title of the abstract too…)

- Tons on PrEP at the meeting, but the study that got the most attention was an interim analysis of a French study of intermittent PrEP, called “IPERGAY”, which stands for … something. Adherence excellent so far in this “event driven” strategy, no outcomes data yet. Note that the comparator arm to the intermittent PrEP is placebo, as PrEP is not approved or strongly endorsed in France.

- More indirect evidence that intermittent PrEP could be the way to go from this iPrEx analysis, which found 100% protection in those participants whose blood levels suggested 4X/week adherence to daily TDF/FTC.

- Don’t share cuticle scissors with someone who is viremic. Enough said.

- There’s no doubt that HIV positive MSM have more anal dysplasia and anal cancer than their HIV negative counterparts, and high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) are thought to be a strong precursor to cancer. But this well done Australian study found that more than half of HSIL lesions regressed spontaneously, making the optimal treatment uncertain. Great name for the study, by the way — Study of the Prevention of Anal Cancer (SPANC).

- In HIV/HCV coinfection (genotypes 1-4), sofosbuvir plus ribavirin cured over 80% of patients, with perhaps the only weakness the genotype 1a patients with cirrhosis. This combination remains the treatment of choice for genotype 2; for genotype 1, sofosbuvir/ledipasvir is imminent.

- Speaking of imminent approvals for genotype 1 HCV, the “3D” regimen of ABT-450/r/ombitasvir (three drugs coformulated) plus dasabuvir plus RBV cured over 95% of coinfected patients. Interestingly, some of them received atazanavir-based regimens, using the “r” (ritonavir) in the HCV regimen to provide the boost.

- A small study of this same combination found that it was safe and effective (again, cure > 95%) in patients on methadone or buprenorphine, with no adjustments required of the narcotic replacement therapy.

- Cure research has taken a beating recently, especially with the virologic relapses of the two Boston stem cell transplant patients and the Mississippi baby. But the research goes on, and here a study demonstrated clearly measurable increases in HIV RNA after infusions of the potent HDAC inhibitor romidepsin — suggesting a reversal of HIV latency! The current thought is that this sort of treatment plus other measures (vaccine? immune augmentation otherwise?) may decrease the latent reservoir.

A few brief impressions of Melbourne, top of the World’s Most Livable City rankings by The Economist since 2011.

- The people were uniformly nice, polite, energetic, and helpful. All of them! There must be some ornery and disagreeable Melbourne natives someplace, but they are either extremely small in number or they are carefully hidden away, far from where tourists roam.

- As a tennis-crazy person, even though I knew it was illogical, I kind of expected Melbourne to be hot — think of the Australian Open in January, matches held in blistering 40 degree celsius heat with blinding sun, players taken into the locker room for IV hydration, etc. Of course this city’s location in the way south of Australia means it’s not “summer” here at all (see the first line up there), it’s just flat-out winter — cool, cloudy, kind of like Seattle in October/November — but nothing (and I mean nothing) like a Boston winter. Wear a sweater and/or a light coat and you’re fine.

- The city has the largest street tram service in the world, and somehow it all works: the streetcars don’t seem to interfere with the traffic or pedestrians, and the stops have incredibly clear and helpful signs telling you not only how long you need to wait for the next car, but the next 3 cars after that. Imagine that on the Boston T on Commonwealth Avenue!

- Food is outstanding, with strong Asian influences everywhere, and many of the restaurants are charmingly located on narrow alleyways, with indoor/outdoor dining overlapping to make the alleys seem like outdoor rooms. Tipping is barely required — kind of viewed as sort of a strange American custom. I asked about tipping in one restaurant, as I didn’t have the right currency for both the bill and a tip, and the waitress said (in all sincerity), “That’s very kind of you, but we’re just fine, thank you.”

- This is a city of true coffee fanatics, proven by the fact that there are only two Starbucks in all of Melbourne — but don’t go to them! From humble little snack bars to high-end bean emporia, the quality of the coffee here is off the charts sensational. Maybe that’s why everyone is so nice? Helpful for jet lag adjustment too.

- Given all of the above wonderfulness, perhaps it’s no surprise that Melbourne is no bargain. (#6 most expensive city in the world, according to this list.) Not eager to see my next credit card statement, yikes.

Next year’s meeting is in Vancouver, which no doubt will celebrate the incredible 1996 Vancouver meeting that introduced effective HIV therapy to the world. Or, to quote Kevin DeCock:

The International AIDS Conference in Vancouver is synonymous with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), now just referred to as ART.

He said it, not me!

July 19th, 2014

Mood Solemn in Melbourne as AIDS 2014 Starts

There is unquestionably a shadow cast over this year’s international AIDS meeting here in Melbourne, and it’s not the result of the Australian winter. It’s the crash of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, of course, which prematurely ended the lives of hundreds of people — including many people en route to this conference, most notably one of the field’s finest clinical researchers and leaders, Joep Lange.

I of course knew Joep (much better than he knew me), and greatly respected his work. He is especially well known for his efforts to make HIV treatments available globally. This achievement is perfectly summarized by Marty Hirsch, quoted in today’s Boston Globe:

He was a leading light, and he was a person who pushed probably as hard or harder than anyone for equity in the field, to make the drugs that we were using in the US and Netherlands available at a low cost for people in underserved areas of the world.

One of his research collaborations is particularly noteworthy given the location of this year’s conference: Along with David Cooper from Sydney and Praphan Phanuphak from Bangkok, Lange was one of the founders of the HIV-NAT Research Collaboration, with NAT standing for “Netherlands Australia Thailand”. This productive effort started in 1995 — one year before combination ART became standard of care! — and was a true model of how countries with diverse backgrounds and economic resources could work together to improve HIV care and research.

Needless to say, everyone here is heartsick about this senseless loss.

July 14th, 2014

Despite Baby’s Relapse, HIV Cure Research Marches On

The big news in the HIV world over the past week was of course the virologic rebound of the Mississippi Baby, who up to this point was considered possibly the second person cured of HIV.

(Timothy Brown — stem-cell transplant recipient from CCR5 negative donor — remains the first and only HIV cure. Every report on this topic needs to mention this, so now I’ve checked that box.)

Obviously this baby’s relapse after over 3 years off treatment was tremendously disappointing — a “punch in the gut” according to one researcher — and, along with the relapse in the Boston stem-cell transplant cases, underscores just how difficult it will be to find a viable strategy for curing this infection.

But it’s equally important to emphasize that significant clinical research in this area has by no means stopped. There’s a vigorous research agenda ongoing in HIV cure, as demonstrated by several studies ongoing in the research network in which I participate (there’s my disclosure), the AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Here are three approaches:

- ACTG A5135: Romidepsin is an in vitro potent HDAC inhibitor (you knew that, right?), which potentially can stimulate latent HIV and hence make it more vulnerable to eradication. You’ll hear more about romidepsin in the upcoming AIDS 2014 Conference in Melbourne, and this ACTG study is enrolling now.

- ACTG A5326: The anti-PD-L1 antibody BMS-936559 can reinvigorate a “fatigued” immune response to HIV, which, along with other strategies, could lead to clearance of the virus. Another study enrolling now.

- ACTG A5308: HIV controllers — those who have undetectable or nearly undetectable HIV RNA even without ART — have smaller HIV reservoirs than most people with HIV. This study will evaluate whether standard ART can reduce this reservoir further, along with improve immunologic abnormalities sometimes observed in these patients. Yes, still enrolling interested participants.

Now none of these will actually cure HIV on their own, but they’re potentially promising first steps. Think of the participants in these studies like these Mercury astronauts, to borrow an analogy from my friend and colleague Joe Eron.

And of course this is just a partial list, with many studies outside the ACTG network also ongoing or planned — including panobinostat (another HDAC inhibitor), zinc finger nucleases, the anti-env cytotoxin 3B3-PE38, other novel gene therapy approaches … Who knows what we’ll hear about next week in Melbourne?

And after that, we can expect more, as there is a tremendous motivation to find the analogous cure strategies to what we have now for HCV. It might be more difficult, but think about the technologies available to us now that barely existed when HIV first was discovered. Kind of like comparing the first home PC to what we have now on our smart phones.

So if the Mississippi baby isn’t cured, and neither are the Boston patients, that doesn’t mean it won’t happen eventually.

Here’s betting it will. A lot of very smart people are working on it, and that’s by no means a comprehensive list. People with lots of brains, unlike the scarecrow.

Enjoy the clip.

June 28th, 2014

CDC Nixes HIV Western Blot in Latest Testing Guidelines

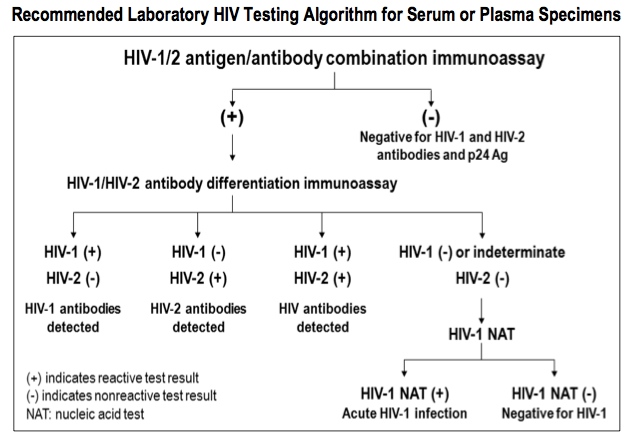

Finally, it’s official — the Western blot is no longer recommended as a confirmatory test for HIV infection. From the latest Laboratory Testing for the Diagnosis of HIV Infection, updated June 27:

The HIV-1 Western blot and HIV-1 immunofluorescence assay, previously recommended to make a laboratory diagnosis of HIV-1 infection, are no longer part of the recommended algorithm.

It’s been clear now for years that the Western blot’s sensitivity for early HIV infection was markedly inferior to the latest generations of HIV screening tests; this difference became even starker with the approval of the combined “fourth generation” antigen/antibody tests.

This put clinicians in the bizarre situation of having to ignore, or disregard, the test that’s supposed to be more accurate than the screening test. Essentially every patient with a positive ELISA and negative Western blot would need a follow-up HIV RNA test of some sort to exclude early HIV. Read here for more information.

I’ve pasted the new recommended algorithm below. Let’s hope that labs that still use the old “reactive ELISA –> Western blot confirmation” practice quickly move to this new approach. And kudos again to HIV Testing Guru (yes, that’s his official title) Bernie Branson for getting this important change into the guidelines.